Checklist |

|

Corresponding author: Yi-Ju Yang ( treefrog@gms.ndhu.edu.tw ) Corresponding author: Si-Min Lin ( lizard.dna@gmail.com ) Academic editor: Anthony Herrel

© 2019 Ko-Huan Lee, Tien-Hsi Chen, Gaus Shang, Simon Clulow, Yi-Ju Yang, Si-Min Lin.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Lee K-H, Chen T-H, Shang G, Clulow S, Yang Y-J, Lin S-M (2019) A check list and population trends of invasive amphibians and reptiles in Taiwan. ZooKeys 829: 85-130. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.829.27535

|

Abstract

Invasive species have impacted biodiversity all around the world. Among various ecosystems, islands are most vulnerable to these impacts due to their high ratio of endemism, highly specialized adaptation, and isolated and unique fauna. As with other subtropical islands, Taiwan faces constant risk of biological invasions and is currently ranked as one of the countries most affected by invasive amphibians and reptiles. In this paper, a comprehensive checklist of all known exotic amphibians and reptiles is provided, including twelve species which have successfully colonized Taiwan and six species with a controversial status. We provide an update on the knowledge of all these species including their distribution, colonization history, threats to native animals, and population trends based on literature records, fauna surveys, and data collected during invasive species eradication and control programs. A list of species with high invasive potentials is also provided. This study reports, for the first time, a comprehensive survey of invasive herpetofauna in Taiwan, which should provide a valuable reference to other regions which might suffer from similar invasion risk.

Keywords

Alien species, CITES, fauna checklist, international trade, island biogeography, IUCN

Introduction

Invasive species have been listed as one of the major threats to global biodiversity (

Taiwan is a medium-sized island located approximately 130 km east from continental Asia. Located at the border between the Palearctic and Indomalaya regions, fauna on this island consists of evolutionary lineages from both of these biogeographic regions (

Like other islands, Taiwan has suffered from biological invasions. Harbors in Taiwan have long played the role of international transfer stations for trade among adjacent regions; a considerable proportion of trade materials includes agricultural products, fishery products, garden plants, live animals, and wildlife products. Furthermore, keeping amphibians and reptiles as pets has become more popular in recent years. Based on a global review of invasive herpetofauna around the world by

In this paper, we provide an up to date and detailed checklist of exotic amphibian and reptile species which have successfully colonized Taiwan. For each species, we collected information on their colonization history, the potential threats they pose to local species and ecosystems, eradication and control attempts conducted by scientists, and some new data collected during these attempts. Finally, we made some broad assumptions on their future trends based upon observations and data collected in field. We hope this will provide a valuable reference for conservation managers both in Taiwan and in other regions that face similar invasion risks.

Materials and methods

We collected all available information on invasive amphibians and reptiles in Taiwan (names and authorities provided in Table

In addition to the above commonly-recognized invasive species, recent studies have provided evidence to suggest that several long-occurring reptile species traditionally considered native to Taiwan may have indeed been relatively recent invaders. These include Mauremys reevesii, Hemidactylus frenatus, Lepidodactylus lugubris, Hemiphyllodactylus typus, and Indotyphlops braminus. The American Bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus, on the other hand, was traditionally thought to be an established invasive species, but there is considerable doubt as to whether they are actually self-sustaining or whether they are simply continually released. Collectively, these species are listed as having a “controversial status”, with relevant discussion below.

Finally, Taiwan is frequently exposed to accidental or intentional release of exotic animals that are not yet considered established and invasive. A large proportion of these animals constitute escaped or released pets. Although frequently reported by animal rescue centers, these species have not yet established breeding populations and are thus not considered invasive. We have categorized these species as “high-risk” that have a high likelihood of establishing as invasive in the future (names and authorities in Table

Results and discussion

Based on our review, we determined that there is a total of three amphibian and nine reptile species that have established stable, invasive populations in Taiwan (Table

| Species | 1st record | Possible origin | Removal fund source | Trend |

| Amphibians | ||||

| Kaloula pulchra Gray, 1831; Banded Bullfrog | 1997 | Timber trades (?) | Government + NGO1 | PE |

| Fejervarya cancrivora (Gravenhorst, 1829); Mangrove Frog | 2005 | Imported fish fry | None | PE |

| Polypedates megacephalus Hallowell, 1861; Spot-legged Tree Frog | 2006 | Horticultural plants | Government + NGO | PE |

| Turtles | ||||

| Trachemys scripta elegans (Wied, 1838); Red-eared Slider | N/A | Intentional release | None | PE |

| Squamata | ||||

| Physignathus cocincinus Cuvier, 1829; Chinese Water Dragon | 2010 | Intentional release | Government + private | PE |

| Chamaeleo calyptratus Duméril and Bibron, 1851; Veiled Chameleon | 2011 | Intentional release | Private people | PP |

| Iguana iguana (Linnaeus, 1758); Common Green Iguana | 2004 | Intentional release | Government | PE |

| Anolis sagrei Dumeril and Bibron, 1837; Brown Anole | 2000 | Horticultural plants | Government + NGO | PE |

| Gekko gecko (Linnaeus 1758); Tokay Gecko | 2008 | Intentional release (?) | Private people | PP |

| Gecko monarchus (Schlegel, 1836); Spotted House Gecko | 2009 | International trades | Government | PE |

| Hemidactylus brookii Gray, 1845; Brook’s House Gecko | 2018 | International trades | None | PE |

| Eutropis multifasciata (Kuhl, 1820); Many-lined Sun Skink | 1992 | Timber trades (?) | Government2 | PE |

| Species with a controversial status | ||||

| Lithobates catesbeianus (Shaw, 1802); American Bullfrog | N/A | Intentional release | None | ? |

| Mauremys reevesii (Gray, 1831); Reeves’ Turtle | 1934 | Intentional release | None | PD |

| Hemidactylus frenatus Dumeril and Bibron, 1836; Common House Gecko | 1885 | Unknown | None | PE |

| Lepidodactylus lugubris (Dumeril and Bibron, 1836); Morning Gecko | 1984 | Unknown | None | PP |

| Hemiphyllodactylus typus Bleeker, 1860; Indopacific Tree Gecko | 1985 | Unknown | None | PP |

| Indotyphlops braminus (Daudin, 1803); Brahminy Blindsnake | ? | Unknown | None | PP |

We determined that one frog (L. catesbeianus), one turtle (M. reevesii), and four squamates should be listed as having a controversial invasion status. In the first case, there is no confirmed evidence that L. catesbeianus has established a stable breeding population in Taiwan. In contrast, M. reevesii and H. frenatus should be revised to be considered as introduced species due to new lines of evidence based on genetic data and historical records (not from this study), both of which are discussed below. The three parthenogenetic squamates, L. lugubris, H. typus, and I. braminus, are considered invasive in Taiwan according to some authors (

In terms of population trends, M. reevesii seems to have experienced dramatic population declines in the late 20th century and has become near-extinct, although the reasons for this are unknown. Several medium- to large-sized lizards (e.g., C. calyptratus and G. gecko) were successfully, albeit temporarily controlled by students and pet keepers, primarily due to their market value, which led to at least a temporary reduction in the population size. One invasive frog (F. cancrivora) appears to be stable in population size, while others have continued to increase in population size over time with no signs of plateauing.

The 14 species summarized in Table

In the following sections, we discuss the detailed information from all the invasive species in these lists.

A list of species with released individuals being frequently discovered, or with high invasive potential.

| Species | Frequency in pet trades1 | Records of escaped individuals2 |

|---|---|---|

| Amphibians | ||

| Cynops orientalis (David, 1873); Oriental Fire-bellied Newt | Very high | Medium |

| Rhinella marina (Linnaeus, 1758); Cane Toad, Marine Toad | Medium | Low |

| Polypedates leucomystax (Gravenhorst, 1829); White-lipped Treefrog | Low | Low |

| Squamata | ||

| Anolis carolinensis Voigt, 1832; Green Anole | Low | Low |

| Salvator merianae (Dumeril & Bibron, 1839); Black-and-white Tegu | High | High |

| Varanus niloticus (Linnaeus, 1766); Nile Monitor | Medium | Medium |

| Varanus salvator (Laurenti, 1768); Common Water Monitor | Medium | Medium |

| Malayopython reticulatus (Schneider, 1801); Reticulated Python | Medium | Medium |

| Python bivittatus Kuhl, 1820; Burmese Python3 | Medium | Medium |

| Turtles | ||

| Macrochelys temminckii Troost, 1835; Alligator Snapping Turtle | High | High |

| Chelydra serpentina (Linnaeus, 1758); Common Snapping Turtles | High | High |

| Pseudemys concinna (Le Conte, 1830); Eastern River Cooter | Very high | Very high |

| Trachemys scripta scripta (Schoepff, 1792); Yellow-bellied Slider | Very high | Very high |

| Crocodilians | ||

| Caiman crocodilus (Linnaeus 1758); Spectacled Caiman | Medium | Medium |

Kaloula pulchra (Gray, 1831)

Natural distribution. As a widely distributed species in South and Southeastern Asia, the west boarder of this medium-sized microhylid frog (Fig.

Colonization history. This species was first reported in 1997 by Yan-Hung Pan, from a military base in Linyuan District, Kaohsiung City (point 1 in Fig.

The distribution and population size of this frog remained limited until the early 21st century. The distribution started to increase after a significant flood in August 2009, which spread the frog to more lowland localities. In an investigation by

Threats to native species and ecosystems. This species is usually abundant in invaded regions, but its threat to local fauna is still obscure. In Taiwan, K. pulchra usually shares similar food items with Duttaphrynus melanostictus (Bufonidae) which preys heavily upon ants and other litter insects. Nevertheless, there is not yet clear evidence that the former represents strong competition with the latter (

A The occurrence of Kaloula pulchra was first discovered in Kaohsiung (1), and later expanded northward to Yunlin, and southward to a disjunct location in Kenting (2) B the skin of this medium- to large-sized microhylid can secret toxins C their tadpoles are commonly found in the invasive regions. Photographed by Gaus Shang (B) and Yin-Hsun Yang (C).

Current status and trends. The invasion dynamics of K. pulchra represented a typical trend of an invasive species: it remained in small numbers for quite a long period, and only started to expand after a “lag time” between initial colonization and the onset of rapid population growth and range expansion (e.g.,

The government initiated several programs to evaluate the distribution and population size of this species since 2005, but the programs did not persist (

Fejervarya cancrivora (Gravenhorst, 1829)

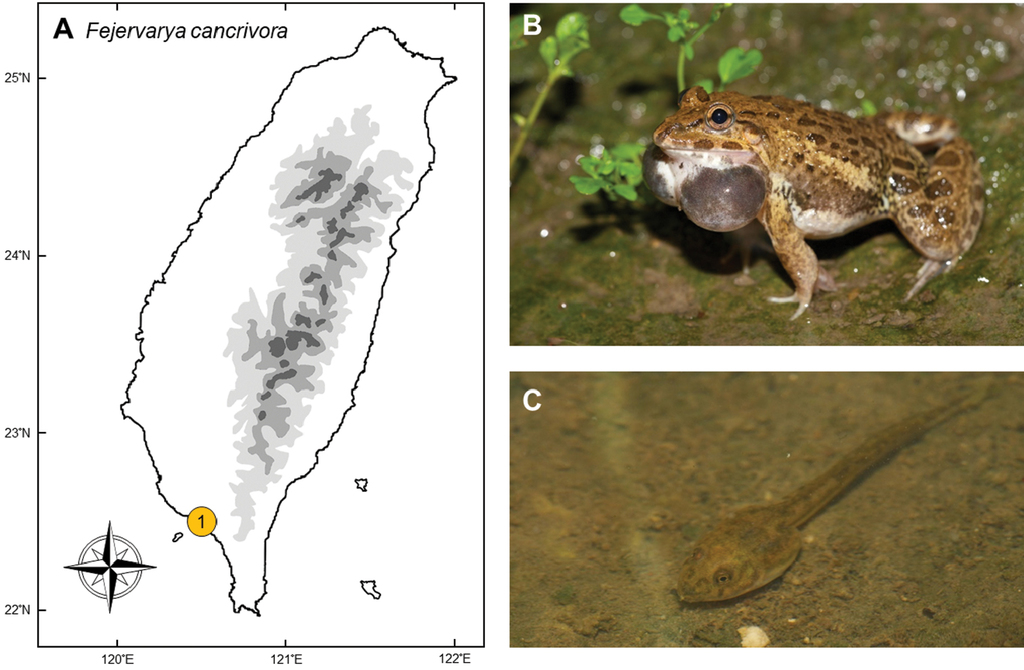

Natural distribution. Inhabiting the coasts and mangroves across south Asia, this robust dicroglossid frog (Fig.

Colonization history. This species was first listed as present in Taiwan by Johnson TF Chen in his first (

In June 2005, this frog was once again discovered by Mr Jia-Hui Lin, a teacher of Renhe primary school, Pingtung County. It was preliminarily identified by Dr Yi-Ju Yang and Cheng-En Li by photograph. Several specimens were later collected in July of the same year, and mating pairs and tadpoles were discovered in October. Fejervarya cancrivora was thus confirmed as a breeding population in southern Taiwan. This frog now has a restricted distribution in Taiwan to the river mouth of Donggang Stream and Linbian Stream, belonging to Donggang, Linbian, Jiadong, and Fangliao townships (point 1 in Fig.

Molecular analyses have shown that this population is closely related to the populations from Borneo, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula, but distantly related to adjacent populations in China and the Philippines (

Threats to native species and ecosystems. Fejervarya cancrivora normally utilizes brackish water, where almost no other amphibians exist. In Taiwan, they utilize fish farms, mangroves, and occasionally occur in orchards of wax apple, where local people use salty water to enhance the fertility of the plants. In inland areas, they sometimes occur in sympatry with native species Fejervarya limnocharis, Microhyla fissipes, and Duttaphrynus melanostictus, but the population is not dominant. Owing to the low to medium abundance of the frog and the lack of relevant research, there is no evidence for competition between F. cancrivora and native species, nor for the effects on the native food-web through predation as well as by being preyed.

Current status and trends. This species is currently found only in Donggang, Linbian, Jiadong, and Fangliao townships of Pingtung County, and also in the mangroves of Dapeng Bay. The population is limited both in abundance and range, with no prominent sign of fast continuing spread. There has not been a proposal to conduct removal or research on this species.

Polypedates megacephalus Hallowell, 1861

Natural distribution. This medium-sized Old-world treefrog (Rhacophoridae, Fig.

Colonization history. This species was first recorded by a citizen of Wuchi, Taichung City who accidently brought a group of tadpoles home with aquatic plants from Tienwei, Changhua in 2006 (point 1 Fig.

A Invasion of Polypedates megacephalus started in central Taiwan (Tienwei (1) and Wuchi (2)), and spread quickly by island hopping from habitat to habitat forward to northern Taiwan (Yingge (3) and Bali (4)) B a mating pair of adults with their foam nest C a small group of P. megacephalus tadpoles. Photographed by Yu-Jen Liang (B) and Gaus Shang (C).

When this species was first found in 2006, it could only be found in Changhua and Taichung. During the first several years, this species formed a disjunct distribution in northern (Taipei and Taoyuan) and central (Taichung and Changhua) Taiwan. It expanded progressively to nearby regions, such as Keelung, Yilan, Hsinchu, Miaoli, Nantou, Yunlin, and Pingtung (

Threats to native species and ecosystems. Polypedates megacephalus preys primarily on small insects, and sometimes small vertebrates such as Gekko hokouensis, Diploderma swinhonis, and Microhyla fissipes (

Current status and trends. This species is still expanding rapidly, with individuals being able to migrate up to 744 meters in a single day (

Monitoring and removal of this species began in 2011, supported by the Forestry Bureau. Hundreds of individuals were removed by volunteers every year from at least four hotspots: Bali (point 4 in Fig.

Current invasion patterns suggest the spread of this species will continue unabated. Management in the near future should focus on how the population size can be depressed and how to maintain the long term viability of native species. Current observations suggest this frog can utilize artificial water bodies and form large populations in disturbed areas. The removal of artificial water bodies could potentially reduce numbers of the frog without being harmful to native species. Ecological corridors between hot spots of this frog could be further interrupted by using fences in order to stop the expansion (

Trachemys scripta elegans (Wied, 1838)

Natural distribution. This freshwater emydid turtle (Fig.

Colonization history. Invasion of this species can be traced to the late decades of 20th Century through intentionally being released by pet owners and religious activities (

Nowadays, this species can be found in many aquatic systems in Taiwan, especially artificial ponds and rivers close to urban areas. Because of the pet market, citizens can get this species very easily, resulting in a fast assisted dispersal rate. Moreover, this species is sold near temples where Buddhists buy animals for their mercy ceremonies, which further facilitate this species to establish new populations.

Threats to native species and ecosystems. This species likely occupies most suitable water bodies through human-mediated dispersal (

A Trachemys scripta elegans can be found in natural, semi-natural, or artificial wetlands in urban or suburban regions all around the island B they are usually found in sympatry with the native Mauremys sinensis C the hatchling turtles show their potential to reproduce in some habitats. Photographed by Gaus Shang (B) and Yu-Jen Liang (C).

Current status and trends. There have been no plans in Taiwan to remove this species from the wild, or to investigate its impacts. The importation and trade continues, with at least hundreds of thousands of young turtles being imported every year. In recent years, the government has invested heavily in development along the river, which has caused dramatic habitat loss on the riverbank. These constructions destroy nesting sites for native turtles located near the river banks. Since T. s. elegans tends to lay their eggs on muddy lands some distance from the riverside, there is likely higher survival rates of these nests leading to potential population replacement of the invasive species over native species (T-HC, pers. obs.).

Based on capture records (

Physignathus cocincinus (Cuvier, 1829)

Natural distribution. This large-sized agamid lizard (Fig.

Colonization history. The first Taiwanese population of Physignathus cocincinus was discovered in Ankeng, New Taipei City in 2010 by a deliveryman who saw an adult lizard basking on the road along a river (point 1 in Fig.

A The invasive population of Physignathus cocincinus was first established by an intentional release in Xindian (1), New Taipei City; and further transferred to Linkou (2), also believed to be intentional B the typical habitat of this semi-aquatic agamid is beside lowland streams C juveniles tend to rest on branches at night. Photographed by Ren-Jay Wang.

Since the core zone of both these invasive populations are in wild, torrential streams which are far from human settlements, they are thought to be established by intentional release. In the late 20th century, P. cocincinus was valued as an alternative pet to the Green Iguana (Iguana iguana) when the latter was prohibited by the Conservation Act of Taiwan. In 2001, captive breeding individuals of I. iguana began to be legally imported, which made P. cocincinus became practically worthless. The origin of the Ankeng and Linkou populations are suspected to be due to releases by pet traders.

Threats to native species and ecosystems. Physignathus cocincinus is omnivorous, but primarily feeds on insects and snails (

Current status and trends. The population in Ankeng did not initially show signs of quick spread because they were usually confined to riparian habitat along streams. During this period, some students, herpers, and pet keepers teamed up to remove this species from the wild. From 2013 to 2017, the government of New Taipei city further held projects to attempt to intensively remove this species. According to these surveys, more than 680 individuals were captured in Ankeng (

Chamaeleo calyptratus (Duméril & Bibron, 1851)

Natural distribution. This large-sized Chamaeleon (Chamaeleonidae; Fig.

Colonization history. This species was first found on Cijin Island, ca. 200 meters offshore of Kaohsiung (point 1 in Fig.

Since the core zone of the chameleon population is located at the tip corner of an isolated peninsular, this invasive population was thought to be established by intentional release. As a popular and valuable animal in pet trades, captive breeding of this species is nevertheless difficult and costly. It was thus deduced that local pet traders released individuals deliberately so that they could “harvest” the young regularly and easily from the wild.

Threats to native species and ecosystems. Chamaeleo calyptratus feeds mainly on insects, although large adults can prey upon small mammals and fledgling birds (

Current status and trends. This species is currently restricted to a hill located on the northwestern corner of Cijin. Although eggs have never been found in the wild, hatchlings and juveniles have been found to constitute a large proportion of the population. Many gravid females have been captured with fertile eggs. Thus it is considered that this species has established a breeding population on the island.

No official project has been stablished to remove this population. However, news of their appearance attracted numerous students, reptile keepers, and pet traders to the island to attempt to catch this valuable pet in the summer of 2013 and 2014. This resulted in the population size decreasing. This species is now difficult to find there, which suggests that hand removal might be an effective management option.

Because this area is connected to Kaohsiung city only by ferry and an underwater tunnel, the spread of this species is likely to remain limited within the island. Nevertheless, invasion risk persists elsewhere with deliberate release from the pet trade.

Iguana iguana (Linnaeus, 1758)

Natural distribution. This iguanid lizard (Fig.

Colonization history. Although a popular pet in international reptile trade, keeping Iguana iguana was illegal in Taiwan until 2001 when the first captive bred individuals were legally imported. During 2002 to 2007, tens of thousands of green iguanas were imported into Taiwan each year (CITES trade database). In 2004, some juvenile I. iguana were found in the wild and sent to Pingtung Rescue Center, suggesting that some individuals had escaped from the pet trade.

Establishment of invasive populations in Taiwan originated from several independent incidents (Fig.

A The invasive populations of Iguana iguana were originally established by multiple intentional release events, specifically in Pingtung (1), Kaohsiung (2), Chiayi (3), and gradually expanded to become a continuous distribution. In 2018, a small disjunct population occurred in Taitung (4), which might be another human-induced translocation event B a mature male occupying the canopy during courtship exhibition C the large number of young lizards demonstrates breeding success. Photographed by Chung-Wei You.

Threats to native species and ecosystems. According to the experience of the Great Caribbean Basin, I. iguana can reach huge population sizes in suitable habitats (

Based on analyses of stomach contents, invasive I. iguana populations in Taiwan feed mostly on Broussonetia papyrifera (Rosales, Moraceae), one of the most abundant shrubs in the disturbed areas of Taiwan. Although we do not have evidence on the threats to native ecosystems in the wild, human agriculture might be seriously damaged from adult iguanas which are able to wipe out the entire crops from the field within a few days. Digging burrows along river banks creates damage to the structure of irrigation channels, which can make structures unstable and threaten the safety of nearby citizens (

Current status and trends. This species first established disjunct populations in southern Taiwan, and then gradually invaded into central Taiwan. During the invasion process, subordinate males play the role of dispersers into novel habitats at the invasion fronts, where they then occupy a territory and become dominant males (Fig.

The Chiayi City Government has offered rewards for invasive Anolis sagrei for several years and I. iguana was included in this rewards program in 2017. However, this approach is considered ineffective by scientists as it has not resulted in population decreases of either of these two species. In southern Taiwan, Kaohsiung City Government conducted another project to evaluate the invasion of I. iguana. More than 2,200 adults were caught in Kaohsiung and Pingtung counties from 2013 to 2017 by T-HC’s laboratory members, and this seems to have effectively reduced the population size (T-HC, unpublished data). We suggest that removal should focus on mature individuals near nesting sites before the breeding season, because dominant adults display strong habitat loyalty during this period (T-HC, pers. obs.). A large proportion of the captured individuals from the government reward program, however, were young lizards which naturally have very low survival rate in winter (T-HC, pers. obs.), which made this program inefficient. We conclude that complete eradication is unlikely in Taiwan; but more efficient management policy could help to depress their population.

Anolis sagrei Duméril & Bibron, 1837

Natural distribution. This small-sized anole (Dactyloidae; Fig.

A The population of Anolis sagrei was first discovered in Jiayi (1), southwestern Taiwan. Subsequently, this lizard occurred long-distance dispersal to eastern (Hualien (2)) and northwestern (Hsinchu (3)) Taiwan B a mature male showing courtship exhibition on a trunk in the invasive region C an egg and a hatchling of A. sagrei. Photographed by Ren-Jay Wang (B) and Wen-Bin Gong (C).

Colonization history. The first record of this species was in September of 2000, when one female and two males were found beside a road near a plant nursery in Sanjiepu, Chiayi by Gerrut Norval (point 1 in Fig.

It remained unknown how this species entered Taiwan, but we deduce that potting compost imported to the nursery likely contained eggs of this species, as was observed during its invasion onto Guana Island (

A. sagrei expands quickly once introduced to new areas and may adapt to new environments well due to its high genetic variation (

Threats to native species and ecosystems. Anolis sagrei occupies the tree-trunk niche within its habitat (Fig.

Current status and trends. In order to persuade citizens to help remove the lizards, the Chiayi County Government has offered rewards for carcasses of the anoles since 2009. However, this policy was regarded as being inefficient. The rewards have encouraged locals to accumulate huge amounts of carcasses, but this has not been effective in removing the population. We suggest several reasons for this: first, most citizens try to catch the lizards from the core zone(s) of the invasion, where high densities of lizards facilitate people to earn the reward with the least effort. However, individuals can quickly fill these gaps from adjacent regions and the population is thus impossible to eliminate. Second, with a long breeding season and continuous clutch production, it is ineffective when only a low proportion of individuals are removed. Although huge amounts of money have been spent on removing individuals every year, the distribution of this species is still expanding rapidly in western Taiwan. In contrast, the research team in Hualien, eastern Taiwan used an alternative strategy. Instead of citizens, volunteers were trained to focus on invasion fronts. By removing individuals from the front, the team led by Dr. Yi-Ju Yang has successfully reduced the speed of the invasion, and successfully eliminated some newly established populations. To date, the Chiayi population is continually expanding, but the expansion in Hualien has been slowed.

Current evaluations indicate that the expansion of Anolis sagrei is unstoppable and that regions which have already been invaded, eradication is likely impossible. The only thing we can do is to slow down the expanding speed of the front. Transportations of potted plants from core regions of lizards should be quarantined (

Gekko gecko (Linnaeus, 1758)

Natural distribution. This large-sized gecko (Gekkonidae; Fig.

Colonization history. Early records of this species in Taiwan can be traced back to the Japanese colonial period (

Rediscovery of this species occurred in 2008, when five individuals were found in Taichung (point 1 in Fig.

A Gekko gecko has been discovered in several disjunct localities (Taichung (1), Kaohsiung (2), Pingtung (3)), which was thought to be from multiple release events B a mature gecko showing defensive posture on a cornice in Kaohsiung C eggs in a nearby cave. Photographed by Ren-Jay Wang (B) and Ko-Huan Lee (C).

Threats to native species and ecosystems. We have recorded individuals regurgitating invasive species of cockroaches after being captured. Therefore, we suspect that they prey mainly upon cockroaches around houses, with some other small invertebrates and vertebrates. Besides direct predation, G. gecko may compete with other native geckos.

Current status and trends. Although distributed sporadically in a few places, only the population in Kaohsiung has been confirmed as a reproducing population. Distribution of this population is restricted to Guishan hill near Lienchi Lake, Zuoying District. Individuals occur around buildings and nearby forests, which is similar habitat to that which this species uses in native areas. There is currently no specific program to eradicate the species. However, the population size has been depressed through spontaneous capturing programs organized by students and pet keepers. Fortunately, Guishan is isolated from nearby natural habitats by urban areas which might prevent G. gecko from spreading to other natural habitats. However, a comprehensive survey is still required to investigate the dynamics of this population, especially with the risk that pet keepers might release more individuals to other localities.

Gekko monarchus (Schlegel, 1836)

Natural distribution. This medium-sized gecko (Gekkonidae; Fig.

Colonization history. This species was first discovered in 2009 from Linyuan District, Kaohsiung by locals (point 1 in Fig.

How this species entered into Taiwan remains unknown, but it is thought to be related to the timber trade of Kaohsiung Harbor (point 1 and 2 in Fig.

A Invasion of Gekko monarchus is thought to have occurred from international timber trades near the Kaohsiung Harbor ((1) and (2)) and a log-processing area (3). In 2018, the newest population was found with disjunt distribution in Taitung County (4) B a mature individual C a large colony of eggs. Photographed by Gaus Shang.

Threat to native species and ecosystems. Gekko monarchus eats small invertebrates in its native range. In Taiwan, it preys primarily upon Coleoptera and Blattodea (Shang et al. 2016), with small snails, egg shells and seeds also occasionally recorded from stomach contents. In invaded regions, this gecko out-competes other geckos such as Lepidodactylus lugubris on Pulau Cebeh (

The most crucial task in the near future would be preventing this species from moving onto Orchid Island, an offshore islet with only 48 km2, which is occupied by Gekko kikuchii (Oshima, 1912), a species closely related to G. monarchus and confined to this island within Taiwan (

Current status and trends. In Taiwan, this species lives close to humans and disturbed areas such as buildings or tunnels (Shang et al. 2016). Shang et al. (2016) estimated the population size of Fengbito to be 5,029 individuals using mark-recapture methods. A large proportion of individuals inhabit military tunnels beneath subtropical forest, which makes them difficult to be eradicated.

An eradication program was conducted by the Forest Bureau from June to December, 2015. A total of 532 individuals were caught, with more than 4,000 eggs being destroyed from three main invaded regions, mostly from Linyuan (Shang et al. 2016). Shang et al. (2016) suggested that removal plans should continue to restrict the population size, and to stop the invasion progress. However, the government seems unwilling to continue the program to eradicate this species. Based on current situation, it has a high potential to spread widely through southern Taiwan within a short period.

Hemidactylus brookii Gray, 1845

Natural distribution. This small-sized gecko (Gekkonidae; Fig.

Colonization history. This recently discovered species was found along the river banks of the Love River in Kaohsiung City (point 1 in Fig.

A Hemidactylus brookii is the most-recent invasive species which was discovered from a single population along the river banks of Love River, Kaohsiung City, southern Taiwan (1) B a mature male C large amount of young geckos indicated that they have successfully colonized in the city. Photographed by Chung-Wei You.

Threat to native species and ecosystems. Feces of H. brookii were collected to identify its diet in Kaohsiung. Diverse insects were identified using microscope, including Coleoptera, Orthoptera, Hemiptera, Diptera, Dermaptera, and Araneae, on which endemic geckos also prey (

Current status and trends. This species mainly dwells in the cement river bank along the Love River, and occasionally spotted in the bushes. A large population was found sympatric with native Gekko hokouensis and suspected invasive Hemidactylus frenatus. The large number of juveniles seen in this population suggests that this species has been breeding in this area, despite no eggs and gravid females were found during the survey. Based on this observation,

Eutropis multifasciata (Kunl, 1820)

Natural distribution. This medium-sized skink (Scincidae; Fig.

Colonization history. This species was first recorded in Meinong District and Chengcing Lake, Kaohsiung in 1992 (

A Eutropis multifasciata has originated from Meinong (1), expanded to the entire southwestern Taiwan, and also colonized offshore islets such as Siao Liouciou (2), Green Island (3), and Orchid Island (4) B an adult male basking on an abandoned tire along a river bank C a mature female with her new-born baby. Photographed by Chung-Wei You (B) and Ren-Jay Wang (C).

Although all of these localities are in western Taiwan, Green Island (point 2) and Orchid Island (point 3), located 33 and 72 km off shore from the east coast of Taiwan, have been reported to contain populations of E. multifasciata. The first record of this species on Green Island was a carcass, presumably killed by cats, in 2008. In the same year, Researcher Te-En Lin, confirmed that a population consisted of approximately one thousand individuals had successfully colonized around the Green Island lighthouse. On the other hand, E. multifasciata has been recorded for several years on Orchid Island with the population size not well documented and time of invasion unknown.

Whether this species immigrated to Green Island and Orchid Island through natural dispersal or artificial introduction remains controversial. For instance, previous research on reptiles (

Threat to native species and ecosystems. Eutropis multifasciata is a viviparous skink which breeds all year round with 4–12 neonates per litter (

Scientists suspect that the congener Eutropis longicaudata would be the first native species to be impacted from the invasion, because E. multifasciata has a much higher fecundity than E. longicaudata. E. longicaudata laid an average of ten eggs three times annually, while E. multifasciata can give birth to 4–12 hatchlings up to five times every year (

Current status and trends. In the early 20th century, E. multifasciata had been one of the major targets of government-funded monitoring. It now appears to be impossible to eradicate, with E. multifasciata having become one of the most abundant skinks south of the Jhuoshuei River, with the highest population density being in southern Taiwan (

Species with a controversial status

Lithobates catesbeianus (Shaw, 1802)

Notes. Captive breeding of this large ranid frog (Fig.

Mature individuals, froglets, and tadpoles are all potential targets for release ceremonies. Therefore, a variety of frog sizes have been discovered in the wild. Nevertheless, despite common records around the low land habitats of Taiwan (Fig.

A Escaped or released Lithobates catesbeianus has been recorded almost all around Taiwan B the injured snout of this adult indicated it is recently released from captivity. However, it seems that they have not established a successful breeding population C one of the very rare cases of tadpoles found in the wild was discovered by Gaus Shang. Photographs by Ren-Jay Wang (B) and Gaus Shang (C).

Mauremys reevesii (Gray, 1831)

Notes. This moderate-sized fresh water geoemydid turtle (Fig.

The first record of this turtle in Taiwan was reported by

A Most confirmed records of Mauremys reevesii in the 20th century are from the Tamsui River Drainage (1) close to the highly developed Taipei City, where this population has gradually gone extinction in the late 1980s B, C the pictures of the adult and the young were taken from a native population on Kinmen, an islet 3 km offshore from China. Photographed by Wei-Lun Lin.

Although currently listed as a threatened native species, this status has recently been challenged by

In order to trace the origin of M. reevesii of which the status was also controversial in Japan,

The reason for the disappearance of this turtle in the Taipei Basin remains a mystery. Habitat destruction could be a major reason, while hybridization and backcross to the dominant native congener M. sinensis could be another, as mitochondrial sequencing has shown hybridization between the species and intermediate forms exist (

Hemidactylus frenatus Dumeril & Bibron, 1836

Notes. This small-sized, house-dwelling gecko (Fig.

Historical observation indicated that H. frenatus and H. bowringii occupied the southern and northern parts of Taiwan, respectively (

A Hemidactylus frenatus has expanded not only throughout the lowland of Taiwan, but also almost all islands in the west Pacific region. The northern one third of Taiwan is believed to have become occupied only in recent decades (indicated by arrows) B a gravid female C the eggs. Photographed by Si-Min Lin.

Lepidodactylus lugubris (Dumeril & Bibron, 1836)

Hemiphyllodactylus typus Bleeker, 1860

Indotyphlops braminus (Daudin, 1803)

Notes. These three small squamates share a common feature: parthenogenesis. They are all regarded as native species in the current literature, and we do not yet have sufficient evidence either to justify, or reject this status. However, the possibility that they are in fact invasive should be reconsidered based on accumulating new lines of evidences.

Lepidodactylus lugubris was first listed as a member of the fauna of Taiwan by Chen’s (1984) revised book, but under the name Gehyra variegate ogasawarasimae Okada 1930, a junior synonym of Lepidodactylus lugubris which was used to refer to the population of Ogasawara Islands. However,

Similar to L. lugubris, Hemiphyllodactylus typus was discovered in central 1980s by

Another species, for which most local biologists are not yet aware of its status as an introduced species, is the brahminy blind snake (Indotyphlops braminus). This parthenogenic snake has been listed in the Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) as an invasive species except for its original habitat in India (

Currently, the two geckos have wide distributions throughout eastern and southern Taiwan, including Orchid Island and Green Island (Figs

Other high-risk species

Fourteen species, including three amphibians, four lizards, two snakes, four turtles, and one crocodilian (listed in Table

The cane toad, Rhinella marina, might be one of the most notorious invasive anurans in the world. Established populations have spread and expanded to huge population sizes in southern Ryukyu, which is located less than 200 km from eastern Taiwan (

The other species listed in Table

We do not consider these large reptiles to currently form invasive populations in Taiwan, but the disastrous cases of invasive reptiles in Ryukyu, Japan and Florida, USA serve as a useful reminder of the potential invasion risks and catastrophic ecological outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Dr Hidetoshi Ota for his careful review on this article with valuable comments, which largely improved the quality of the original manuscript. We also thank the assistance from those who dedicated in the removal and investigation of these invasive species, including: Prof Hsueh-Wen Chang, Researcher De-En Lin, Mr Meng-Hsien Chuang, Mr Chung-Wei You, assistants and students including Wei-Chieh Hsu, Shih-Bin Tsai, Bo-Kai Chiou, Ping-Hsiang Chang, Dun-Li You, Wen-Bin Gong, Li-Yu Chen, Chien-Wei Chin, Chien-Chih Chen, Che-U Chang, Kai-Chieh Hsieh, Chiung-Chen Cheng, Chia-Ming Tsao, Yu Li, and numerous volunteers in these removal processes especially for P. megacephalus and A. sagrei. We appreciate the photographers for providing excellent photos, including Ren-Jay Wang, Chung-Wei You, Yin-Hsun Yang, Yu-Jen Liang, Wei-Lun Lin, and Wen-Bin Gong. This paper combines the results from different grants provided to the removal or investigation of various invasive species, including: Forestry Bureau, Council of Agriculture for P. megacephalus (104-08-SB-28, 105-08.1-SB-28, 106-08.1-SB-28), P. cocincinus, I. iguana, and G. monarchus; Kenting National Park Headquarters for K. pulchra, T. s. elegans, and E. multifasciata (486-103-03); Agriculture Bureau of New Taipei City for P. cocincinus; Agriculture Bureau of Kaohsiung City for I. iguana; and Hualien Forest District of Forestry Bureau for A. sagrei.

References

- Bauer AM, Pauwels OSG, Sumontha M (2002) Hemidactylus brookii brookii – Distribution. Herpetological Review 33: 322.

- Bauer AM, Branch WR (2004) An accidental importation of Gekko monarchus into Africa. Hamadryad 28: 125–126.

- Bauer AM, Jackman TR, Greenbaum E, Giri VB, de Silva A (2010) South Asia supports a major endemic radiation of Hemidactylus geckos. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 57: 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2010.06.014

- Bellard C, Cassey P, Blackburn TM (2016) Alien species as a driver of recent extinctions. Biology letters 12: 20150623. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2015.0623

- Behm JE, van Buurt G, DiMarco BM, Ellers J, Irian CG, Langhans KE, McGrath K, Tran TJ, Helmus MR (2019) First records of the mourning gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris Duméril & Bibron, 1836), common house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus in Duméril, 1836), and Tokay gecko (Gekko gecko Linnaeus, 1758) on Curaçao, Dutch Antilles, and remarks on their Caribbean distributions. BioInvasions Records 8.

- Blackburn TM, Cassey P, Duncan RP, Evans KL, Gaston KJ (2004) Avian extinction and mammalian introductions on oceanic islands. Science 305: 1955–1958. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1101617

- Boulenger GA (1885) Catalogue of the Lizards in the British Museum (Nat. Hist.) I. Geckonidae, Eublepharidae, Uroplatidae, Pygopodidae, Agamidae. Order of the Trustees, London, 450 pp.

- Burgin S (2006) Confirmation of an established population of exotic turtles in urban Sydney. Australian Zoologist 33: 379–384. https://doi.org/10.7882/AZ.2006.011

- Burnett S (1997) Colonizing cane toads cause population declines in native predators: reliable anecdotal information and management implications. Pacific Conservation Biology 3: 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1071/PC970065

- Cadi A, Joly P (2003) Competition for basking places between the endangered European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis galloitalica) and the introduced red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans). Canadian Journal of Zoology 81: 1392–1398. https://doi.org/10.1139/z03-108

- Cadi A, Joly P (2004) Impact of the introduction of the red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) on survival rates of the European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis). Biodiversity and conservation 13: 2511–2518. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BIOC.0000048451.07820.9c

- Cadi A, Delmas V, Pre´vot-Julliard AC, Joly P, Pieau C, Girandot M (2004) Successful reproduction of the introduced slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans) in the South of France. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 14: 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.607

- Caillabet OS (2013) The Trade in Tokay Geckos Gekko gecko in South-east Asia: with a case study on Novel Medicinal Claims in Peninsular Malaysia. Traffic Press, Petaling Jaya, 34 pp.

- Campbell TS (1996) Northern range expansion of the brown anole (Anolis sagrei) in Florida and Georgia. Herpetological Review 27: 155–157.

- Capinha C, Seebens H, Cassey P, García‐Díaz P, Lenzner B, Mang T, Moser D, Pyšek P, Rödder D, Scalera R, Winter M, Dullinger S, Essl F (2017) Diversity, biogeography and the global flows of alien amphibians and reptiles. Diversity and Distributions 23: 1313–1322. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12617

- Carranza S, Arnold E (2006) Systematics, biogeography, and evolution of Hemidactylus geckos (Reptilia: Gekkonidae) elucidated using mitochondrial DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 38: 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2005.07.012

- Case TJ, Bolger DT, Petren K (1994) Invasions and competitive displacement among house geckos in the tropical Pacific. Ecology 75: 464–477. https://doi.org/10.2307/1939550

- Chang CU (2016) Movement and habitat use of the alien species, Polypedates megacephalus, in Taichung Metropolitan Park. Master’s thesis, Hualien, Taiwan: National Dong Hwa University. [In Chinese with English abstract]

- Chang HW, Liu KC (1995) The distribution of viviparous skinks in southern Taiwan. Notes and Newsletter of Wildlifers 3: 8.

- Chang NC (2007) The newly recorded alien lizard, Anolis sagrei, in Hualien. Nature Conservation Quarterly 57: 37–41. [In Chinese]

- Chang YH, Wu BY, Lu HL (2013) A study on the use of ecological fences for protection against Polypedates megacephalus. Ecological engineering 61: 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.09.068

- Chang YM (2012) Controlling and monitoring populations of the invasive frog, Kaloula pulchra, in Taiwan (101FD-7.1-C-33(1)). Forestry Bureau, Taipei. http://conservation.forest.gov.tw/File.aspx?fno=61742 [Accessed 2 February 2018; In Chinese with English abstract]

- Charles H, Dukes JS (2008) Impacts of invasive species on ecosystem services. In: Nentwig W (Ed.) Biological invasions. Ecological Studies (Analysis and Synthesis), vol 193, Springer, Berlin, 217–237.

- Chen CC (2015) Distribution of alien tree frog (Polypedates megacephalus) in Taiwan. Master’s thesis, Hualien, Taiwan: National Dong Hwa University. [In Chinese with English abstract]

- Chen JTF (1956) A Synopsis of the Vertebrates of Taiwan, Vol. 1. The Commercial Press Ltd., Taipei, 548 pp. [In Chinese]

- Chen JTF (1969) A Synopsis of the Vertebrates of Taiwan. Revised Edition. The Commercial Press Ltd., Taipei, 440 pp. [In Chinese]

- Chen JTF, Yu MJ (1984) A Synopsis of the Vertebrates of Taiwan. Revised and Enlarged Edition (in 3 vols), Vol III. Commercial Press, Taipei, 633 pp. [In Chinese]

- Chen LY (2014) Diet of the invasive tree frog (Polypedates megacephalus) in Taiwan. Master’s thesis, Hualien, Taiwan: National Dong Hwa University. [In Chinese with English abstract]

- Chen TH, Lue KY (1998) Ecological notes on feral populations of Trachemys scripta elegans in northern Taiwan. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 3: 87–90.

- Chen TH, Lue KY (2010) Population status and distribution of freshwater turtles in Taiwan. Oryx 44: 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605310000013

- Chen TH (2006) Distribution and status of the introduced red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) in Taiwan. In: Koike F, Clout MN, Kawamichi M, De Poorter M, Iwatsuki K (Eds) Assessment and Control of Biological Invasion Risks. Shoukadoh Book Sellers, Kyoto and IUCN, Gland, 187–195.

- Chen TH (2015) The investigation and management of invasive amphibians and reptiles in Kenting National Park (486-103-03). Kenting National Park, Kenting. http://ws.ktnp.gov.tw/Download.ashx?u=LzAwMS9VcGxvYWQvMjQ1L3JlbGZpbGUvNjczMi85NTYxMS8yMDE1MTIxNl8xNDA1MTkuMTA1MjEucGRm&n=MjAxNTEyMTZfMTQwNTE5LjEwNTIxLnBkZg%3d%3d&icon=.10521 [Accessed 2 February 2018; in Chinese with English abstract]

- Christy MT, Clark CS, Gee II DE, Vice D, Vice DS, Warner MP, Tyrrell CL, Rodda GH, Savidge JA (2007a) Recent records of alien anurans on the Pacific Island of Guam. Pacific Science 61: 469–483. https://doi.org/10.2984/1534-6188(2007)61[469:RROAAO]2.0.CO;2

- Christy MT, Savidge JA, Rodda GH (2007b) Multiple pathways for invasion of anurans on a Pacific island. Diversity and Distributions 13: 598–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00378.x

- Chu HP (2000) An exotic species of lizard introduced in southern Taiwan – Mabuya multifasciata. Nature Conservation Quarterly 29: 50–53.

- Ciou BK (2015) Study on food habits of the invasive Asian water dragon Physignathus cocincinus in Taiwan. Master’s thesis, Taipei, Taiwan: National Taipei University of Education. [In Chinese with English abstract]

- Conant R, Collins JT (1998) A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, 640 pp.

- Das I (2015) A field guide to the reptiles of South-East Asia. Bloomsbury Press, London, 376 pp.

- Degenhardt G, Painter C, Price A (1996) Amphibians and Reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 431 pp.

- Diesmos AC, Diesmos ML, Brown R (2006) Status and distribution of alien invasive frogs in the Philippines. Journal of Environmental Science and Management 9: 41–53.

- Doherty TS, Glen AS, Nimmo DG, Ritchie EG, Dickman CR (2016) Invasive predators and global biodiversity loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 11261–11265. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602480113

- Early R, Bradley BA, Dukes JS, Lawler JJ, Olden JD, Blumenthal DM, Gonzalez P, Grosholz ED, Ibañez I, Miller LP, Sorte CJB, Tatem AJ (2016) Global threats from invasive alien species in the twenty-first century and national response capacities. Nature Communications 7: 12485. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12485

- Ernst CH (1990) Systematics, taxonomy, variation, and geographic distribution of the slider turtle. In: Gibbons JW (Ed.) Life history and ecology of the slider turtle. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC, 57–67.

- Falcón W, Ackerman JD, Daehler CC (2012) March of the green iguana: Non-native distribution and predicted geographic range of Iguana iguana in the Greater Caribbean Region. IRCF Reptiles and Amphibians 19: 150–160.

- Falcón W, Ackerman JD, Recart W, Daehler CC (2013) Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 10. Iguana iguana, the Green Iguana (Squamata: Iguanidae). Pacific Science 67: 157–186. https://doi.org/10.2984/67.2.2

- Fei L, Ye CY, Jiang JP (2012) Colored atlas of Chinese amphibians and their distributions [In Chinese]. Sichuan Science and Technology Press, Sichuan, 619 pp.

- Ferriter A, Doren B, Winston R, Thayer D, Miller B, Thomas B, Barrett M, Pernas T, Hardin S, Lane J, Kobza M, Schmitz D, Bodle M, Toth L, Rodgers L, Pratt P, Snow S, Goodyear C (2009) Chapter 9: The Status of Nonindigenous Species in the South Florida Environment. In: Redfield G (Ed.) South Florida Environmental Report. South Florida Water Management District, West Palm Beach, 1–101.

- Fong JJ, Chen TH (2010) DNA evidence for the hybridization of wild turtles in Taiwan: possible genetic pollution from trade animals. Conservation Genetics 11: 2061–2066. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-010-0066-z

- Fritts TH, Rodda GH (1998) The role of introduced species in the degradation of island ecosystems: a case history of Guam. Annual review of Ecology and Systematics 29: 113–140. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.113

- Gerber GP, Echternacht AC (2000) Evidence for asymmetrical intraguild predation between native and introduced Anolis lizards. Oecologia 124: 599–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420000414

- Gill BJ, Bejakovich D, Whitaker AH (2001) Records of foreign reptiles and amphibians accidentally imported to New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology 28: 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014223.2001.9518274

- Greene BT, Yorks DT, Parmerlee JS, Powell R, Henderson RW (2002) Discovery of Anolis sagrei in Grenada with comments on its potential impact on native anoles. Caribbean Journal of Science 38: 270–272.

- Grismer LL (2011a) Amphibians and Reptiles of the Seribuat Archipelago (Peninsula Malaysia). Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt am Main, 239 pp.

- Grismer LL (2011b) Lizards of Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore and their Adjacent Archipelagos. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt am Main, 728 pp.

- Gurevitch J, Padilla DK (2004) Are invasive species a major cause of extinctions? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 19: 470–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.005

- Harlow PS, Thomas N (2010) American iguana eradication project: herpetologists’ final report. In: Duffy L (Ed.) Emergency Response to Introduced Green Iguanas in Fiji. CEPF and CI-Pacific, Apia, 59–65.

- Heidy Kikillus K, Hare K M, Hartley S (2010) Minimizing false‐negatives when predicting the potential distribution of an invasive species: A bioclimatic envelope for the red‐eared slider at global and regional scales. Animal Conservation 13: 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2008.00299.x

- Henderson RW, Villa J, Dixon JR (1976) Lepidodactylus lugubris (Reptilia: Gekkonidae). A recent addition to the herpetofauna of Nicaragua. Herpetological Review 7: 173.

- Henderson RW, De Latte A, McCarthy TJ (1993) Gekko gecko (Sauria: Gekkonidae) established on Martinique, French West Indies. Caribbean Journal of Science 29: 128–129.

- Hikida T (1988) A new white-spotted subspecies of Eumeces chinensis (Scincidae: Lacertilia) from Lutao Island, Taiwan. Japanese Journal of Herpetology 12: 119–123. https://doi.org/10.5358/hsj1972.12.3_119

- Hikida T, Suzuki D (2010) The introduction of the Japanese populations of Chinemys reevesii estimated by the descriptions in the pharmacopias in the Edo Era. Bulletin of the Herpetological Society of Japan 2010: 31–36.

- Horikawa Y (1934) Turtles of Taiwan. The Taiwan Jiho 181: 7–16. [In Japanese]

- Hou PCL (2011) Controlling and monitoring populations of the invasive frog, Kaloula pulchra, in Taiwan (IV) (100FD-7.1-C-26(2)). Forestry Bureau, Taipei. http://conservation.forest.gov.tw/File.aspx?fno=61742 [Accessed 2 February 2018; in Chinese with English abstract]

- Hou PCL, Tu MC, Mao JJ (2007) Monitoring distribution of the invasive Asiatic painted frog (Kaloula pulchra) and pilot study on eradication of the brown anole (Anolis sagrei) in Taiwan (95-00-8-04). Forestry Bureau, Taipei. http://conservation.forest.gov.tw/File.aspx?fno=63065 [accessed 2 February 2018; in Chinese with English abstract]

- Huang SC, Norval G, Tso IM (2008) Predation by an exotic lizard, Anolis sagrei, alters the ant community structure in betelnut palm plantations in southern Taiwan. Ecological entomology 33: 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.2008.00995.x

- Hulme PE (2014) Invasive species challenge the global response to emerging diseases. Trends in parasitology 30: 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2014.03.005

- Hunsaker D (1966) Notes on the population expansion of the house gecko, Hemidactylus frenatus. Philippine Journal of Science 95: 121–122.

- Hunsacker D, Breese P (1967) Herpetofauna of the Hawaiian Islands. Pacific Science 11: 423–428.

- Ineich I (1999) Spatio-temporal analysis of the unisexual-bisexual Lepidodactylus lugubris complex (Reptilia, Gekkonidae). In: Ota H (Ed.) Tropical Island Herpetofauna : Origin, Current Diversity and Conservation. Elsevier, Developments in Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Amsterdam, 199–228.

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2015) Lithobates catesbeianus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T58565A53969770. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T58565A53969770.en [Accessed 25 April 2018]

- Júnior JCR (2015) Occurrence of the Tokay Gecko, Gekko gecko Linnaeus 1758 (Squamata, Gekkonidae), an exotic species in southern Brazil. Herpetology Notes 8: 8–10.

- Karsen SJ, Lau MWN, Bogadek A (1998) Hong Kong Amphibians and Reptiles,2nd Ed. Urban Council, Hong Kong, 186 pp.

- King W, Krakauer T (1966) The exotic herpetofauna of southeast Florida. Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 29: 144–154.

- Kishinami ML, Kishinami CH (1996) New records of lizards established on Oahu. Bishop Museum Occasional Papers 46: 45–46.

- Kluge AG (1969) The evolution and geographical origin of the New World Hemidactylus mabouia-brookii complex (Gekkonidae, Sauria). Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 138: 1–78.

- Kolbe JJ, Glor RE, Schettino LR, Lara AC, Larson A, Losos JB (2004) Genetic variation increases during biological invasion by a Cuban lizard. Nature 431: 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02807

- Kowarik I (1995) Time lags in biological invasions with regard to the success and failure of alien species. In: Pyšek P (Ed.) Plant invasions: general aspects and special problems. Balogh Scientific Books, Champaign, IL, 15–38.

- Kraus F, Fern D (2004) New records of alien reptiles and amphibians in Hawai‘i. In: Evenhuis NL, Eldredge LG (Eds) Records of the Hawaii Biological Survey for 2003—Part 2: Notes. Bishop Museum, Hawai‘i, 62–64.

- Kraus F (2009) Alien Reptiles and Amphibians: A Scientific Compendium and Analysis. Springer, New York, 563 pp. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8946-6

- Krysko KL, Enge KM, King FW (2004) The veiled chameleon, Chamaeleo calyptratus Duméril and Bibron 1851 (Sauria: Chamaeleonidae): A new exotic species in Florida. Florida Scient 67: 249–253. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.emo087700

- Krysko KL, MacKenzie-Krysko C (2016) First report of the Mourning Gecko, Lepidodactylus lugubris (Duméril & Bibron, 1836), from The Bahamas. Caribbean Herpetology 54: 1–2. https://doi.org/10.31611/ch.54

- Kuraishi N, Matsui M, Hamidy A, Belabut DM, Ahmad N, Panha S, Sudin A, Yong HS, Jiang JP, Ota H, Thong HT, Nishikawa K (2013) Phylogenetic and taxonomic relationships of the Polypedates leucomystax complex (Amphibia). Zoologica Scripta 42: 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.2012.00562.x

- Kurita K, Hikida T (2014) Divergence and long-distance overseas dispersals of island populations of the Ryukyu five-lined skink, Plestiodon marginatus (Scincidae: Squamata), in the Ryukyu Archipelago, Japan, as revealed by mitochondrial DNA phylogeography. Zoological Science 31: 187–194. https://doi.org/10.2108/zs130179

- Kurita K, Nakamura Y, Okamoto T, Lin SM, Hikida T (2017) Taxonomic reassessment of two subspecies of Chinese skink in Taiwan based on morphological and molecular investigations (Squamata, Scincidae). ZooKeys 687: 131–148. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.687.12742

- Kurniawan N, Islam MM, Djong TH, Igawa T, Daicus MB, Yong HS, Wanichanon R, Khan MMR, Iskandar DT, Nishioka M, Sumida M (2010) Genetic divergence and evolutionary relationship in Fejervarya cancrivora from Indonesia and other Asian countries inferred from allozyme and mtDNA sequence analyses. Zoological Science 27: 222–233. https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.27.222

- Lai JS, Lue KY (2008) Two new Hynobius (Caudata: Hynobiidae) salamanders from Taiwan. Herpetologica 64: 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1655/06-065.1

- Lajmi A, Giri VB, Karanth KP (2016) Molecular data in conjunction with morphology help resolve the Hemidactylus brookii complex (Squamata: Gekkonidae). Organisms Diversity & Evolution 16: 659–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13127-016-0271-9

- Lapwong Y, Juthong W (2018) New records of Lepidodactylus lugubris (Duméril & Bibron, 1836) (Squamata, Gekkonidae) from Thailand and a brief revision of its clonal composition in southeast Asia. Current Herpetology 37: 143–150. https://doi.org/10.5358/hsj.37.143

- Letnic M, Webb JK, Shine R (2008) Invasive cane toads (Bufo marinus) cause mass mortality of freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnstoni) in tropical Australia. Biological Conservation 141: 1773–1782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.04.031

- Liang SKP (2005) A study on the impact from exotic Asiatic painted frog (Kaloula pulchra) in Taiwan and its origin. Master’s thesis, Taipei, Taiwan: National Taiwan Normal University. [In Chinese with English abstract]

- Lin DE (2008) Notes and Suggestion to prevent the spread of the alien species, Mabuya multifasciata. Nature Conservation Quarterly 61: 30–36. [In Chinese]

- Lin HD, Chen YR, Lin SM (2012) Strict consistency between genetic and topographic landscapes of the brown tree frog (Buergeria robusta) in Taiwan. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 62: 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2011.09.022

- Lin JY, Cheng HY (1990) Lizards of Taiwan. Taiwan Museum Press, Taipei, 176 pp. [In Chinese]

- Lin MI (2007) A study on the origin and population genetic structure of Asiatic painted frog (Kaloula pulchra) in Taiwan. Master’s thesis, Taipei, Taiwan: National Taiwan Normal University. [In Chinese with English abstract]

- Ling CS (1972) Turtle sacrifice in China and Oceania. Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, Taipei, 122 pp.

- Lever C (2003) Naturalized reptiles and amphibians of the world. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 318 pp.

- López-Torres AL, Claudio-Hernández HJ, Rodriguez-Gomez CA, Longo AV, Joglar RL (2012) Green Iguanas (Iguana iguana) in Puerto Rico: is it time for management? Biological invasions 14: 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-0057-0

- Losos JB, Marks JC, Schoener TW (1993) Habitat use and ecological interaction of an introduced and native species of Anolis lizard on Grand Cayman, with a review of the outcomes on anole introductions. Oecologia 95: 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00317437

- Lorvelec O, Levesque A, Bauer AM (2011) First record of the Mourning Gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris) on Guadeloupe, French West Indies. Herpetology Notes 4: 291–294.

- Lorvelec O, Barré N, Bauer AM (2017) The status of the introduced Mourning Gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris) in Guadeloupe (French Antilles) and the high probability of introduction of other species with the same pattern of distribution. Caribbean Herpetology 57: 1–7. https://doi.org/10.31611/ch.57

- Lovich JE, Yasukawa Y, Ota H (2011) Mauremys reevesii (Gray 1831) – Reeves’ Turtle, Chinese Three-keeled Pond Turtle. In: Rhodin AGJ, Pritchard PCH, van Dijk PP, Saumure RA, Buhlmann KA, Iverson JB, Mittermeier RA (Eds) Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. Chelonian Research Monographs No. 5. Chelonian Research Foundation, Massachusetts, 050.1–050.10. https://doi.org/10.3854/crm.5.050.reevesii.v1.2011

- Lowe S, Browne M, Boudjelas S, De Poorter M (2000) 100 of the world’s worst invasive alien species: a selection from the Global Invasive Species database. New Zealand: Invasive Species Specialist Group, Auckland, 11 pp.

- Lue KY, Chen SH, Chen YS, Chen SL (1987) Reptiles of Taiwan – Lizards. Education Administration, Ministry of Education, Taichung, 116 pp. [In Chinese]

- Lue KY, Lai JS (1990) The Amphibians of Taiwan. Education Administration, Ministry of Education, Taichung, 110 pp. [In Chinese]

- Lue KY, Tu MC, Chen SH, Lue SY, Zhuang GS (1985) The lakes and herpetofauna survey in Nanjenshan. National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei. [In Chinese]

- Luiselli L, Capula M, Capizzi D, Philippi E, Truillo-Jesus V, Anibaldi C (1997) Problems for conservation of pond turtles (Emys orbicularis) in central Italy: is the introduced red-eared turtle (Trachemys scripta) a serious threat? Chelonian Conservation and Biology 2: 417–419.

- Ma K, Shi H (2017) Red-eared slider Trachemys scripta elegans (Wied-Neuwied). In: Wan F, Jiang M, Zhan A (Eds) Biological invasions and its management in China. Invading nature – Springer series in invasion ecology, vol 13. Springer, Singapore, 49–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3427-5_4

- Mahony S (2011) Taxonomic revision of Hemidactylus brookii Gray: a re-examination of the type series and some Asian synonyms, and a discussion of the obscure species Hemidactylus subtriedrus Jerdon (Reptilia: Gekkonidae). Zootaxa 3042: 37–67.

- Manthey U, Grossmann W (1997) Amphibien and Reptilien Südostasiens [In German]. Natur und Tier Verlag, Münster, 512 pp.

- Mao SH (1971) Turtles of Taiwan. Commercial Press, Taipei, 123 pp.

- McKeown S (1996) A field guide to reptiles and amphibians in the Hawaiian islands. Diamond Head Publishing, Los Osos, 172 pp.

- Menzies JI (1996) Unnatural distribution of fauna in the East Malesian region. In: Kitchener DJ, Suyanto A (Eds) Proceedings of the First International Conference on Eastern Indonesian–Australian Vertebrate Fauna, Manado, Indonesia, 22–26 November 1994, Western Australian Museum for Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia, Perth, 31–38. Meshaka Jr WE, Bartlett RD, Smith HT (2004) Colonization success by green iguanas in Florida. Iguana 11: 154–161.

- Meshaka Jr WE (1999) The herpetofauna of the Kampong. Florida Scientist 62: 153–157.

- Meyer L, Du Preez L, Verneau O, Bonneau E, Héritier L (2015) Parasite host-switching from the invasive American red-eared slider, Trachemys scripta elegans, to the native Mediterranean pond turtle, Mauremys leprosa, in natural environments. Aquatic Invasions 10: 79–91. https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2015.10.1.08

- Mito T, Uesugi T (2004) Invasive alien species in Japan: the status quo and the new regulation for prevention of their adverse effects. Global Environmental Research 8: 171–193.

- Mooney HA, Cleland EE (2001) The evolutionary impact of invasive species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98: 5446–5451. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.091093398

- Moritz C, Case TJ, Bolger DT, Donnellan S (1993) Genetic diversity and the history of Pacific island house geckos (Hemidactylus and Lepidodactylus). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 48: 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1993.tb00882.x

- Norval G, Brown L, Mao JJ, Slater K (2017) A description of the characteristics of the habitats preferred by the brown anole (Anolis sagrei Dumeril and Bibron 1837), an exotic invasive lizard species in southwestern and eastern Taiwan. In: Yen SH (Ed.) Congress of Animal Behavior and Ecology (Taiwan), January 2017. National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung.

- Norval G, Bursey CR, Goldberg SR, Mao JJ, Slater K (2011) Origin of the helminth community of an exotic invasive lizard, the brown anole, Anolis sagrei (Squamata: Polychrotidae), in southwestern Taiwan. Pacific Science 65: 383–390. https://doi.org/10.2984/65.3.383

- Norval G, Dieckmann S, Huang SC, Mao JJ, Chu HP, Goldberg SR (2011) Does the tokay gecko (Gekko gecko [Linnaeus, 1758]) occur in the wild in Taiwan. Herpetology Notes 4: 203–205.

- Norval G, Mao JJ, Chu HP, Chen LC (2002) A new record of an introduced species, the brown anole (Anolis sagrei) (Duméril & Bibron, 1837), in Taiwan. Zoological Studies 41: 332–336. https://doi.org/10.15560/13.2.2083

- O’Dowd DJ, Green PT, Lake PS (2003) Invasional ‘meltdown’on an oceanic island. Ecology Letters 6: 812–817. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00512.x

- Okada Y (1936) Studies on the lizards of Japan. Contribution. I. Gekkonidae. Science Reports of the Tokyo Bunrika Daigaku Section B 42: 233–289.

- Old Bridge Association of Kaohsiung (2016) Removal and investigation of invasive amphibians. Forestry Bureau, Taipei. http://conservation.forest.gov.tw/File.aspx?fno=67180 [Accessed 2 February 2018; in Chinese]

- Oliveros CH, Moyle RG (2010) Origin and diversification of Philippine bulbuls. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 54: 822–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2009.12.001

- Ota H (1986) The mourning gecko Lepidodactylus lugubris (Dumcril & Bibron, 1836); an addition to the herpetofauna of Taiwan. Journal of Taiwan Museum 39: 55–58.

- Ota H (1995) A review of introduced reptiles and amphibians of the Ryukyu Archipelago Japan. Island Studies in Okinawa 13: 63–78.

- Ota H (1989) A review of the geckos (Lacertilia: Reptilia) of the Ryukyu Archipelago and Taiwan. In: Matsui M, Hikida T, Goris RC (Eds) Current Herpetology in East Asia. Herpetological Society of Japan, Kyoto, 222–261.

- Ota H, Toda M, Masunaga G, Kikukawa A, Toda M (2004) Feral population of amphibians and reptiles in the Ryukyu archipelago, Japan. Global Environmental Research 8: 133–143.

- Ota H (2009) Winter low temperature and its effects on animals in the subtropical islands of Okinawa. In: Yamazato K (Ed.) The Flexible Meridional Philosophy of Okinawa. Okinawa Times, Naha, 140–156. [In Japanese]

- Ota H, Huang WS (2000) Mabuya cumingi (Reptilia: Scincidae): An addition to the herpetofauna of Lanyu Island, Taiwan. Current Herpetology 19: 57–61. https://doi.org/10.5358/hsj.19.57

- Ota H, Chang HW, Liu KC, Hikida T (1994) A new record of the viviparous skink, Mabuya multifasciata (Kuhl, 1820) (Squamata: Reptilia), from Taiwan. Zoological Studies 33: 86–89.

- Ota H, Toda M, Masunaga G, Kikukawa A, Toda Ma (2004) Feral populations of amphibians and reptiles in the Ryukyu Archipelago, Japan. Global Environmental Research 8: 133–143.

- Pauwels OSG, Sumontha M (2007) Geographical distribution. Gekko monarchus (Malaysia House Gecko). Herpetological Review 38: 218.

- Perry G, Powell R, Watson H (2006) Keeping invasive species off Guana Island, British Virgin Islands. Iguana 13: 273–277.

- Polo-Cavia N, Gonzalo A, López P, Martín J (2010) Predator recognition of native but not invasive turtle predators by naïve anuran tadpoles. Animal Behaviour 80: 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.06.004

- Ramsay NF, Ng PKA, O’Riordan RM, Chou LM (2007) The red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) in Asia: A review. In: Gherardi F (Ed.) Biological invaders in inland waters: profiles, distribution, and threats. Springer, Dordrecht, 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6029-8_8

- Rodríguez Schettino L (1999) Iguanid lizards of Cuba. University Press of Florida, Florida, 448 pp.

- Romer JD (1977) Reptiles new to Hong Kong. Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 17: 232–234.

- Rösler H, Bauer AM, Heinicke MP, Greenbaum E, Jackman T, Nguyen TQ, Ziegler T (2011) Phylogeny, taxonomy, and zoogeography of the genus Gekko Laurenti, 1768 with the revalidation of G. reevesii Gray, 1831 (Sauria: Gekkonidae). Zootaxa 2989: 1–50.

- Roughgarden J (1995) Anolis Lizards of the Caribbean: Ecology, Evolution, and Plate Tectonics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 226 pp.

- Sakai AK, Allendorf FW, Holt JS, Lodge DM, Molofsky J, With KA, Baughman S, Cabin RJ, Cohen JE, Ellstrand NC, McCauley DE, O’Neil P, Parker IM, Thompson JN, Weller SG (2001) The population biology of invasive species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 32: 305–332. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037

- Satheeshkumar P (2011) First record of a mangrove frog Fejervarya cancrivora (Amphibia: Ranidae) in the Pondicherry mangroves, Bay of Bengal-India. World Journal of Zoology 6: 328–330.

- Sax DF, Gaines SD (2008) Species invasions and extinction: the future of native biodiversity on islands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105: 11490–11497. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0802290105

- Sementelli A, Smith HT, Meshaka Jr WE, Engeman RM (2008) Just green iguanas? The associated costs and policy implications of exotic invasive wildlife in South Florida. Public works management & policy 12: 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X08316157

- Shang G (2001) Natural Portraits of Lizards of Taiwan. Bigtrees Press, Taipei, 176 pp. [In Chinese]

- Shang G (2013) What is the potential threat of invasive species to the biggest gecko on Lanyu Island, Taiwan? The Quarterly Journal of Nature 121: 4–11. [in Chinese]

- Shang G, Yang YJ, Li PH (2009) Field guide to amphibians and reptiles in Taiwan. Owl Publishing House Company, Taipei, 336 pp. [in Chinese]

- Shi H, Parham JF, Fan Z, Hong M, Yin F (2008) Evidence of massive scale of turtle farming in China. Oryx 42: 147–150. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605308000562

- Shi HT (2000) Results of turtle market surveys in Chengdu and Kunming. Turtle and Tortoise Newsletter 6: 15–16.

- Shih HT, Hung HC, Schubart CD, Chen CA, Chang HW (2006) Intraspecific genetic diversity of the endemic freshwater crab Candidiopotamon rathbunae (Decapoda, Brachyura, Potamidae) reflects five million years of the geological history of Taiwan. Journal of Biogeography 33: 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01472.x

- Shine R (2010) The ecological impact of invasive cane toads (Bufo marinus) in Australia. The Quarterly Review of Biology 85: 253–291. https://doi.org/10.1086/655116

- Siler CD, Oaks JR, Cobb K, Ota H, Brown RM (2014) Critically endangered island endemic or peripheral population of a widespread species? Conservation genetics of Kikuchi’s gecko and the global challenge of protecting peripheral oceanic island endemic vertebrates. Diversity and Distributions 20: 756–772. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12169

- Steven GP, Lance WF (1994) Anolis sagrei. Herpetological Review 25: 33.

- Suzuki D, Ota H, Oh HS, Hikida T (2011) Origin of Japanese populations of Reeves’ pond turtle, Mauremys reevesii (Reptilia: Geoemydidae), as inferred by a molecular approach. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 10: 237–249. https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-0885.1

- Suzuki D, Yabe T, Hikida T (2013) Hybridization between Mauremys japonica and Mauremys reevesii inferred by nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analyses. Journal of Herpetology 48: 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1670/11-320

- Tan HH, Lim KK (2012) Recent introduction of the brown anole Norops sagrei (Reptilia: Squamata: Dactyloidae) to Singapore. Nature in Singapore 5: 359–362.

- Telecky TM (2001) United States import and export of live turtles and tortoises. Turtle and Tortoise Newsletter 4: 8–13.

- Thomas M, Hartnell P (2000) An occurrence of a red-eared turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans) in the Waikato river at Hamilton, New Zealand. Herpetofauna 30: 15–17.

- Thomas N, Macedru K, Mataitoga W, Surumi J, Qeteqete S, Niukula J, Naikatini A, Heffernan A, Fisher R, Harlow P (2011) Iguana iguana: A feral population in Fiji. Oryx 45: 321–322.

- Tilbury C (2010) Chameleons of Africa, an Atlas including the chameleons of Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt am Main, 831 pp.

- To A (2005) Another alien has landed: the discovery of a wild population of water dragon, Physignathus cocincinus, in Hong Kong. Porcupine 33: 3–4.

- Toda M, Nishida M, Matsui M, Lue KY, Ota H (1998) Genetic variation in the Indian rice frog, Rana limnocharis (Amphibia: Anura), in Taiwan, as revealed by allozyme data. Herpetologica 54: 73–82.

- Tseng HY, Lin DE (2008) Investigation of the northern boundary of the alien species, Mabuya multifasciata. Nature Conservation Quarterly 61: 37–42. [In Chinese]

- Tseng HY, Huang WS, Jeng ML, Villanueva RJT, Nuñeza OM, Lin CP (2018) Complex inter‐island colonization and peripatric founder speciation promote diversification of flightless Pachyrhynchus weevils in the Taiwan–Luzon volcanic belt. Journal of Biogeography 45: 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13110

- Tseng SP, Li SH, Hsieh CH, Wang HY, Lin SM (2014) Influence of gene flow on divergence dating-implications for the speciation history of Takydromus grass lizards. Molecular Ecology 23: 4770–4784. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12889

- Tseng SP, Wang CJ, Li SH, Lin SM (2015) Within-island speciation with an exceptional case of distinct separation between two sibling lizard species divided by a narrow stream. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 90: 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2015.04.022

- Uchida I (1989) The current status of feral turtles of Japan. Anima 205: 80–85.

- UNEP/WCMC (2017) CITES trade statistics derived from the CITES Trade Database, UNEP World Conservation. Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK. https://trade.cites.org/

- Vassilieva AB, Galoyan EA, Poyarkov NA, Geissler P (2016) A photographic field guide to the amphibians and reptiles of the lowland monsoon forests of southern Vietnam. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt am Main, 324 pp.

- Vuillaume B, Valette V, Lepais O, Grandjean F, Breuil M (2015) Genetic evidence of hybridization between the endangered native species Iguana delicatissima and the invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in the Lesser Antilles: management implications. PloS one 10: e0127575. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127575

- Wang GQ (2013) Modeling the dispersal pattern of brown anole (Anolis sagrei) population in Samtzepu, Chiayi County, Taiwan. Master’s thesis, Tainan, Taiwan: National Cheng Kung University. [In Chinese with English abstract]

- Wang S, Xie Y (2009) China species red list: vol. 2. Higher Education Press, Beijing, 1481 pp. [in Chinese]

- Wang YH, Hsiao YW, Lee KH, Tseng HY, Lin YP, Komaki S, Lin SM (2017) Acoustic differentiation and behavioral response reveals cryptic species within Buergeria treefrogs (Anura, Rhacophoridae) from Taiwan. PloS one 12: e0184005. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184005

- Wu HC, Lin CF, Yeh TC, Lue KY (2010) Life history of the spot-legged tree frog Polypedates megacephalus in captivity. Taiwan Journal of Biodiversity 12: 177–186. [In Chinese with English abstract]

- Wu SP, Huang CC, Tsai CL, Lin TE, Jhang JJ, Wu SH (2016) Systematic revision of the Taiwanese genus Kurixalus members with a description of two new endemic species (Anura, Rhacophoridae). ZooKeys 557: 121–153. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.557.6131