Research Article |

|

Corresponding author: Laetitia M. Gunton ( laetitia.gunton@austmus.gov.au ) Academic editor: Greg Rouse

© 2021 Laetitia M. Gunton, Elena K. Kupriyanova, Tom Alvestad, Lynda Avery, James A. Blake, Olga Biriukova, Markus Böggemann, Polina Borisova, Nataliya Budaeva, Ingo Burghardt, Maria Capa, Magdalena N. Georgieva, Christopher J. Glasby, Pan-Wen Hsueh, Pat Hutchings, Naoto Jimi, Jon A. Kongsrud, Joachim Langeneck, Karin Meißner, Anna Murray, Mark Nikolic, Hannelore Paxton, Dino Ramos, Anja Schulze, Robert Sobczyk, Charlotte Watson, Helena Wiklund, Robin S. Wilson, Anna Zhadan, Jinghuai Zhang.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation:

Gunton LM, Kupriyanova EK, Alvestad T, Avery L, Blake JA, Biriukova O, Böggemann M, Borisova P, Budaeva N, Burghardt I, Capa M, Georgieva MN, Glasby CJ, Hsueh P-W, Hutchings P, Jimi N, Kongsrud JA, Langeneck J, Meißner K, Murray A, Nikolic M, Paxton H, Ramos D, Schulze A, Sobczyk R, Watson C, Wiklund H, Wilson RS, Zhadan A, Zhang J (2021) Annelids of the eastern Australian abyss collected by the 2017 RV ‘Investigator’ voyage. ZooKeys 1020: 1-198. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1020.57921

|

Abstract

In Australia, the deep-water (bathyal and abyssal) benthic invertebrate fauna is poorly known in comparison with that of shallow (subtidal and shelf) habitats. Benthic fauna from the deep eastern Australian margin was sampled systematically for the first time during 2017 RV ‘Investigator’ voyage ‘Sampling the Abyss’. Box core, Brenke sledge, and beam trawl samples were collected at one-degree intervals from Tasmania, 42°S, to southern Queensland, 24°S, from 900 to 4800 m depth. Annelids collected were identified by taxonomic experts on individual families around the world. A complete list of all identified species is presented, accompanied with brief morphological diagnoses, taxonomic remarks, and colour images. A total of more than 6000 annelid specimens consisting of 50 families (47 Polychaeta, one Echiura, two Sipuncula) and 214 species were recovered. Twenty-seven species were given valid names, 45 were assigned the qualifier cf., 87 the qualifier sp., and 55 species were considered new to science. Geographical ranges of 16 morphospecies extended along the eastern Australian margin to the Great Australian Bight, South Australia; however, these ranges need to be confirmed with genetic data. This work providing critical baseline biodiversity data on an important group of benthic invertebrates from a virtually unknown region of the world’s ocean will act as a springboard for future taxonomic and biogeographic studies in the area.

Keywords

Biodiversity, Biogeography, deep sea, Echiura, lower-bathyal, Marine Parks, Polychaeta, Sipuncula, Tasman Sea

Introduction

The deep sea (> 200 m depth) is the least explored environment on our planet, where most species have not been sampled and remain undiscovered. The vast sediments of the deep sea cover approximately 65% of the Earth’s surface, and it is a unique environment characterised by darkness, low temperatures and low currents, high hydrostatic pressure, and well oxygenated oligotrophic waters (

In Australia, the abyssal plain (3000 to 6000 m depth) and deep ocean floor covers ~ 2.8 million km2, or 30% of Australia’s marine territory (

Earlier sampling of the eastern Australian abyss was performed as part of research expeditions to the area organised by non-Australian institutions. These include expeditions dating back to the H.M.S. ‘Challenger’ expedition (1874, the UK), the ‘Galathea’ expedition (1951–52, Denmark), the research vessel (RV) ‘Dmitry Mendeleev’ (1975–76, USSR), and RV ‘Tangaroa’ voyages (1982, New Zealand) (reviewed in

A new era for deep-sea biological exploration in Australia began in 2014 with the launch of the Marine National Facility’s RV ‘Investigator’, the first Australian research vessel equipped to routinely perform biological sampling to depths of 5000 m. The systematic biological study of abyssal depths in Australia on board RV ‘Investigator’ started with the Great Australian Bight (GAB) Research Program. This programme conducted six surveys off the southern coastline of Australia during 2013, 2015, and 2017, sampling epifauna from soft substrates, rocky outcrops in canyons and seamounts from depths of 200–5000 m (

The significant gap in knowledge about the eastern abyss was addressed by the 2017 ‘Sampling the Abyss’ research project supported by the Marine National Facility, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (

Annelids occur in all marine environments and they are typically a dominant macrofauna (> 300 µm) taxon in terms of abundance and species diversity in deep-sea soft sediments (

This study reports an illustrated and annotated preliminary species-level checklist of the annelid fauna collected during the 2017 ‘Sampling the Abyss’ survey along with species diversity and distribution data. Morphospecies are compared with those collected from the GAB sampling programme where possible.

Annelid species described below 1000 m in Australian waters (roughly corresponding to Exclusive Economic Zone, 12 nautical miles from the coast). Bold font indicates species from eastern Australian margin.

| Family | Species | Depth (m) | Type Locality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polynoidae | Lepidasthenia australiensis (Augener, 1927) | 1000 | Off eastern Victoria |

| Sabellidae | Potaspina australiensis Capa, 2007 | 1000 | South of Point Hicks, Victoria |

| Polynoidae | Brychionoe karenae Hanley & Burke, 1991 | 1100 | Cascade Plateau off Tasmania |

| Onuphidae | Paradiopatra imajimai Paxton & Budaeva, 2013 | 1277 | Off eastern Victoria |

| Polynoidae | Lagisca torbeni Kirkegaard, 1995 | 1320–1340 | Great Australian Bight, south of Adelaide |

| Polynoidae | Harmothoe australis Kirkegaard, 1995 | 1340 | Great Australian Bight, south of Adelaide |

| Spionidae | Laonice pectinata Greaves, Meißner & Wilson, 2011 | 1440 | Indian Ocean, west of Perth |

| Onuphidae | Paradiopatra spinosa Paxton & Budaeva, 2013 | 1600 | Bass Canyon |

| Polynoidae | Eunoe ivantsovi Averincev, 1978 | 1640 | Lord Howe Island Rise |

| Polynoidae | Eunoe papillaris Averincev, 1978 | 1800 | Off southwestern Tasmania |

| Nephtyidae | Aglaophamus profundus Rainer & Hutchings, 1977 | 2195 | Off northeastern Tasmania |

| Polynoidae | Parapolyeunoa flynni (Benham, 1921) | 2379 | Off Maria Island, Tasmania |

| Fauveliopsidae | Fauveliopsis challengeriae McIntosh, 1922 | 3566 | South Indian Ocean, midway between Australia and Antarctica |

| Polynoidae | Eunoe abyssorum McIntosh, 1885 | 4755 | South of Australia |

| Polynoidae | Polynoe ascidioides McIntosh, 1885 (now considered a nomen dubium) | 4755 | South of Australia |

Materials and methods

Sampling area

The eastern Australian continental shelf is relatively narrow compared with the rest of the continent. The shelf break occurs ~ 15 km from the coast and the foot-of-slope and beginning of the abyssal plain can be as close as 60 km from the coast (

The East Australian Current (EAC) is an important shallow water current carrying ~ 22–27 Sverdrups from north to south along the east coast of Australia. This counter-clockwise southern Pacific gyre circulates shallow water from the Coral Sea along the continental margin until 32–35°S before heading eastward to New Zealand. Part of the EAC is deflected offshore ~ 30°S along the Tasman Front, this divides the warm waters of the Coral Sea and the cooler waters of the Tasman Sea (

Field collection and processing

Biological samples were collected from 13 sites at one-degree intervals of latitude from 42°S to 24°S along the east coast of Australia from Tasmania to Southern Queensland (Fig.

Sample Sites. Beam trawl, Brenke sledge, and box core deployments on RV ‘Investigator’ cruise IN2017_V03 from the Australian eastern lower bathyal and abyssal environment. Abbreviations: Op., operation, BT,

| Op. | Location | Gear | Date | Start latitude and longitude | End latitude and longitude | Trawling distance (km) | Start depth (m) | End depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 004 | Freycinet MP | BT | 18/05/17 | -41.731, 149.120 | -41.791, 149.156 | 7.3 | 2820 | 2751 |

| 005 | Freycinet MP | BS | 18/05/17 | -41.730, 149.135 | -41.753, 149.147 | 2.8 | 2789 | 2779 |

| 006 | Freycinet MP | BT | 18/05/17 | -41.626, 149.552 | -41.689, 149.584 | 7.5 | 4022 | 4052 |

| 007 | Freycinet MP | BC | 18/05/17 | -41.647, 149.570 | 4030 | |||

| 008 | Freycinet MP | BC | 19/05/17 | -41.647, 149.569 | 4012 | |||

| 009 | Freycinet MP | BS | 19/05/17 | -41.626, 149.560 | -41.662, 149.574 | 4.2 | 4021 | 4035 |

| 011 | Freycinet MP | BC | 19/05/17 | -41.721, 149.125 | 2793 | |||

| 013 | Flinders MP | BT | 20/05/17 | -40.386, 148.928 | -40.383, 148.951 | 2.0 | 932 | 1151 |

| 014 | Flinders MP | BT | 20/05/17 | -40.464, 149.102 | -40.461, 149.147 | 3.8 | 2298 | 2486 |

| 015 | Flinders MP | BT | 20/05/17 | -40.473, 149.397 | -40.464, 149.426 | 2.6 | 4114 | 4139 |

| 016 | Flinders MP | BS | 21/05/17 | -40.463, 149.415 | -40.461, 149.364 | 4.3 | 4129 | 4131 |

| 017 | Flinders MP | BC | 21/05/17 | -40.460, 149.109 | s | 2331 | ||

| 022 | Bass Strait | BT | 22/05/17 | -39.462, 149.276 | -39.465, 149.242 | 2.9 | 2760 | 2692 |

| 023 | Bass Strait | BS | 22/05/17 | -39.462, 149.277 | -39.465, 149.246 | 2.7 | 2774 | 2694 |

| 027 | Bass Strait | BC | 22/05/17 | -39.462, 149.271 | 2741 | |||

| 028 | Bass Strait | BC | 22/05/17 | -39.500, 149.535 | 4147 | |||

| 030 | Bass Strait | BT | 23/05/17 | -39.552, 149.553 | -39.496, 149.598 | 7.3 | 4197 | 4133 |

| 031 | Bass Strait | BS | 23/05/17 | -39.422, 149.604 | -39.391, 149.597 | 3.5 | 4150 | 4170 |

| 032 | East Gippsland MP | BT | 24/05/17 | -38.479, 150.185 | -38.453, 150.186 | 2.9 | 3850 | 3853 |

| 033 | East Gippsland MP | BS | 24/05/17 | -38.521, 150.213 | -38.498, 150.207 | 2.6 | 4107 | 4064 |

| 035 | East Gippsland MP | BT | 25/05/17 | -37.792, 150.382 | -37.818, 150.353 | 3.9 | 2338 | 2581 |

| 040 | East Gippsland MP | BS | 25/05/17 | -37.815, 150.373 | -37.818, 150.356 | 1.5 | 2746 | 2600 |

| 041 | off Bermagui | BT | 26/05/17 | -36.418, 150.800 | 3980 | |||

| 042 | off Bermagui | BS | 26/05/17 | -36.385, 150.863 | -36.434, 150.863 | 5.4 | 4744 | 4716 |

| 043 | off Bermagui | BT | 27/05/17 | -36.351, 150.914 | -36.384, 150.913 | 3.7 | 4800 | 4800 |

| 044 | off Bermagui | BT | 27/05/17 | -36.355, 150.644 | -36.315, 150.651 | 4.5 | 2821 | 2687 |

| 045 | off Bermagui | BS | 27/05/17 | -36.360, 150.644 | -36.323, 150.650 | 4.1 | 2835 | 2739 |

| 046 | off Bermagui | BC | 27/05/17 | -36.284, 150.658 | 2643 | |||

| 053 | Jervis MP | BT | 28/05/17 | -35.114, 151.469 | -35.084, 151.441 | 4.2 | 3952 | 4011 |

| 054 | Jervis MP | BS | 28/05/17 | -35.117, 151.473 | -35.099, 151.455 | 2.6 | 4026 | 3881 |

| 055 | Jervis MP | BS | 28/05/17 | -35.335, 151.259 | -35.334, 151.219 | 3.6 | 2667 | 2665 |

| 056 | Jervis MP | BT | 29/05/17 | -35.333, 151.258 | -35.332, 151.214 | 4.0 | 2650 | 2636 |

| 57* | Jervis MP | BC | ||||||

| 065 | off Newcastle | BT | 30/05/17 | -33.441, 152.702 | -33.435, 152.665 | 3.5 | 4280 | 4173 |

| 066 | off Newcastle | BS | 30/05/17 | -33.448, 152.733 | -33.437, 152.674 | 5.6 | 4378 | 4195 |

| 067 | off Newcastle | BT | 31/05/17 | -32.985, 152.952 | -33.015, 152.913 | 4.9 | 2704 | 2902 |

| 068 | off Newcastle | BS | 31/05/17 | -32.993, 152.957 | -33.023, 152.943 | 3.6 | 2745 | 2963 |

| 069 | Hunter MP | BT | 03/06/17 | -32.479, 152.994 | -32.507, 152.991 | 3.1 | 1006 | 1036 |

| 070 | Hunter MP | BT | 03/06/17 | -32.575, 153.162 | -32.632, 153.142 | 6.6 | 2595 | 2474 |

| 076 | Hunter MP | BS | 03/06/17 | -32.577, 153.161 | -32.613, 153.149 | 4.2 | 2534 | 2480 |

| 078 | Hunter MP | BT | 04/06/17 | -32.138, 153.527 | -32.182, 153.524 | 4.9 | 3980 | 4029 |

| 079 | Hunter MP | BS | 04/06/17 | -32.131, 153.527 | -32.163, 153.524 | 3.6 | 4031 | |

| 080 | Central Eastern MP | BT | 05/06/17 | -30.099, 153.596 | -30.128, 153.571 | 4.0 | 1257 | 1194 |

| 086 | Central Eastern MP | BT | 05/06/17 | -30.098, 153.899 | -30.119, 153.875 | 3.3 | 2429 | 2518 |

| 087 | Central Eastern MP | BS | 06/06/17 | -30.113, 153.898 | -30.116, 153.867 | 3.0 | 2634 | 2324 |

| 088 | Central Eastern MP | BT | 06/06/17 | -30.264, 153.870 | -30.287, 153.830 | 4.6 | 4481 | 4401 |

| 089 | Central Eastern MP | BS | 06/06/17 | -30.263, 153.859 | -30.289, 153.844 | 3.2 | 4436 | 4414 |

| 090 | off Byron Bay | BT | 07/06/17 | -28.677, 154.203 | -28.709, 154.190 | 3.8 | 2587 | 2562 |

| 096 | off Byron Bay | BS | 07/06/17 | -28.678, 154.204 | -28.716, 154.189 | 4.5 | 2591 | 2566 |

| 097 | off Byron Bay | BT | 08/06/17 | -28.355, 154.636 | -28.414, 154.615 | 6.9 | 3762 | 3803 |

| 098 | off Byron Bay | BS | 08/06/17 | -28.371, 154.647 | -28.389, 154.612 | 4.0 | 3811 | 3754 |

| 099 | off Byron Bay | BT | 09/06/17 | -28.371, 154.649 | -28.388, 154.617 | 3.7 | 3825 | 3754 |

| 100 | off Byron Bay | BT | 09/06/17 | -28.054, 154.083 | -28.097, 154.081 | 4.8 | 999 | 1013 |

| 101 | off Moreton Bay | BT | 09/06/17 | -26.946, 153.945 | -26.971, 153.951 | 2.8 | 2520 | 2576 |

| 102 | off Moreton Bay | BT | 10/06/17 | -27.008, 154.223 | -27.049, 154.224 | 4.6 | 4274 | 4264 |

| 103 | off Moreton Bay | BS | 10/06/17 | -27.000, 154.223 | -27.061, 154.223 | 6.8 | 4260 | 4280 |

| 104 | off Moreton Bay | BT | 10/06/17 | -26.961, 153.848 | -26.991, 153.847 | 3.3 | 1071 | 1138 |

| 109 | off Fraser Island | BT | 11/06/17 | -25.221, 154.164 | -25.253, 154.192 | 4.5 | 4006 | 4005 |

| 110 | off Fraser Island | BS | 11/06/17 | -25.220, 154.160 | -25.261, 154.200 | 6.1 | 4005 | 4010 |

| 115 | off Fraser Island | BT | 11/06/17 | -25.325, 154.068 | -25.351, 154.076 | 3.0 | 2350 | 2342 |

| 118** | off Fraser Island | BS | ||||||

| 119 | off Fraser Island | BS | 12/06/17 | -25.206, 153.991 | -25.178, 153.979 | 3.3 | 2247 | 2369 |

| 121 | Coral Sea MP | BT | 13/06/17 | -23.587, 154.194 | -23.617, 154.195 | 3.3 | 1013 | 1093 |

| 122 | Coral Sea MP | BT | 13/06/17 | -23.751, 154.639 | -23.773, 154.616 | 3.4 | 2369 | 2329 |

| 123 | Coral Sea MP | BS | 13/06/17 | -23.749, 154.641 | -23.774, 154.617 | 3.7 | 2271 | 2339 |

| 128 | Coral Sea MP | BT | 13/06/17 | -23.631, 154.660 | -23.659, 154.644 | 3.5 | 1770 | 1761 |

| 131 | Coral Sea MP | BS | 14/06/17 | -23.748, 154.643 | -23.778, 154.613 | 4.5 | 2297 | 2358 |

| 132 | Coral Sea MP | BS | 14/06/17 | -23.756, 154.568 | -23.780, 154.540 | 3.9 | 2181 | 2132 |

| 134 | Coral Sea MP | BS | 14/06/17 | -23.750, 154.572 | -23.774, 154.546 | 3.8 | 2093 | 2156 |

| 135 | Coral Sea MP | BT | 15/06/17 | -24.352, 154.291 | -24.384, 154.325 | 5.0 | 3968 | 4034 |

The

The Brenke sledge (mesh size 1 mm) was used to collect microbenthic infauna living near the sediment-water interface and more mobile epibenthic fauna (

Prior to fixation, all specimens were weighed and registered on board and assigned labels with operation (op) and accession numbers (acc).

Annelid specimens collected during the voyage were shipped to the Australian Museum, Sydney (

Laboratory identification of annelids

At the respective institutions, annelids fixed in formalin were soaked in water, preserved with 80% ethanol and sorted in 80% ethanol, while ethanol-fixed annelids were sorted in 95% ethanol. Mixed lots of annelids were sorted to families at the

All beam trawl specimens were identified. Brenke sledge and box core material was identified past family level when specimens were large enough (considered adult) and/or complete. Annelids were assigned Latin binomial names where possible or determined in open nomenclature following

The matrix of all annelid species-level abundance and presence data (including beam trawl, box core, and Brenke sledge material) from voyage IN2017_V03 was constructed in MS Excel in standardised Darwin Core format.

Results

Taxonomic overview

Family Acoetidae Kinberg, 1856

A. Murray

This family of scale worms is characterised by the presence of internal ‘spinning’ glands which produce fibres used to construct their tough fibrous permanent tubes. These fibres often appear as golden strings emerging from the notopodia. Acoetidae are active carnivores and predators, and most frequently collected by fishers on baited lines, in shallow to deep waters (1–200 m). There are currently nine valid genera with 58 nominal species worldwide (

Panthalis

Diagnosis

One damaged specimen, with 24 anterior segments measuring 1.2 cm long, 0.6 mm wide. Head region badly damaged, but some features recognisable: low rounded ommatophores without necks and colourless, a single long median antenna attached mid-prostomium, longer than prostomium length; lateral antennae and palps missing, however; tentaculophores with a few chaetae, styles missing; elytra present on segments 2, 4, 5, 7 and alternating segments thereafter, delicate, transparent. All chaetae simple. Acicular neurochaetae starting from chaetiger 3, notochaetae absent from chaetiger 4 and on all parapodia thereafter. Notopodia with notoaciculum and spinning glands internally, golden ‘spinning’ fibres emergent from the inner surface of the notopodial bract. Superior group of neurochaetae from chaetiger 9 onwards, of two types: long, with plumose (brush) tips, and shorter chaetae with few whorls of short widely spaced hairs along shafts; middle group of neurochaetae stout, acicular chaetae with hairy aristate tips; inferior group of neurochaetae curved, lanceolate, with many transverse rows of overlapping spines along shaft.

Remarks

This specimen possesses brush-tipped neurochaetae typical of the genera Acoetes and Panthalis, but lacks notochaetae in all middle segments, a feature which distinguishes it as a species of Panthalis. The genus Panthalis has not yet been reported from Australian waters; however, specimens have been collected previously from deep water in the Arafura Sea off Western Australia and Northern Territory (

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

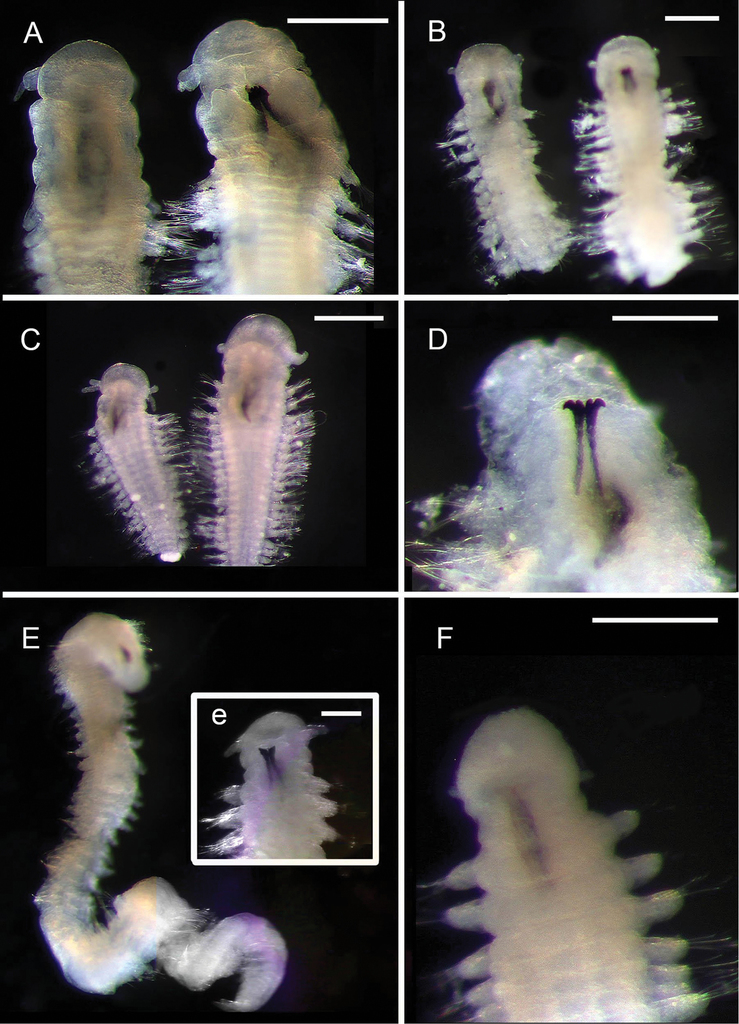

Acoetidae, Chrysopetalidae, Nephtyidae, Oweniidae A Acoetidae, Panthalis sp., dorsal view (

Family Acrocirridae Banse, 1969

N. Jimi

Acrocirridae are generally small, thread-like or maggot-shaped worms, which are predominantly benthic. There are currently nine valid genera with 43 nominal species (

Chauvinelia

Diagnosis

Length 1.5 mm, width 0.4 mm, 19 chaetigers, two pairs of branchiae, palps lost. Large ventral papillae present in anterior achaetous segments. Notochaetae elongated, simple, spinous in the tip. Neurochaetae elongated, compound, spinous in the tip.

Records

5 specimens. Suppl. material

Flabelligella

Records

1 specimen: Suppl. material

Flabelligena

Diagnosis

Length ~ 15 mm, width 1–2 mm, 31–35 chaetigers, prostomium subpentagonal, three pairs of branchiae, two or three spinous notochaetae, one or two composite neurochaetae, short lateral cirri. Body papillae short, with sediment particles. Large ventral papillae absent.

Records

12 specimens. Suppl. material

Flabelligena

Diagnosis

Incomplete, length ~ 7 mm, width 0.5 mm, ~ 18 chaetigers, prostomium subpentagonal, three pairs of branchiae, one or two spinous notochaetae, one composite neurochaetae, long lateral cirri in posterior chaetigers. Body papillae short, without attached sediment particles. Large ventral papillae present.

Records

5 specimens. Suppl. material

Flabelligena

Diagnosis

Length ~ 7 mm, width 0.5 mm, 13 chaetigers, prostomium subpentagonal, two pairs of branchiae, one or two spinous notochaetae, one or two composite neurochaetae, short lateral cirri. Body papillae very short, without attached sediment particles. Large ventral papillae absent.

Records

4 specimens. Suppl. material

Flabelligena

Diagnosis

Length ~ 7 mm, width 0.5 mm, 40 chaetigers, prostomium subpentagonal, two pairs of branchiae, three or four spinous notochaetae, 2–4 composite neurochaetae, pair of short lateral cirri. Body papillae very short, with attached sediment particles. Large ventral papillae present.

Records

6 specimens. Suppl. material

Flabelligena spp.

Records

6 specimens. Suppl. material

Swima

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Acrocirridae

Diagnosis

Incomplete, length ~ 7 mm, width 0.4 mm, ~ 17 chaetigers, prostomium subpentagonal, ~ four pairs of branchiae, two or three notochaetae, three or four composite neurochaetae. Body papillae short, without sediment particles. Large ventral papillae absent.

Records

14 specimens. Suppl. material

Acrocirridae

Diagnosis

Incomplete (posterior fragment), length ~ 10 mm, width 0.7 mm, 25 chaetigers, 1–2 spinous notochaetae, one composite short neurochaetae. Body papillae short, with sediment particles. Large ventral papillae absent. Similar to Flabelligena sp. 1, but different in neurochaetal shape.

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Acrocirridae

Diagnosis

Incomplete, length ~ 4 mm, width 0.4 mm, 12 chaetigers, 2–3 notochaetae, 2–3 composite neurochaetae. Body papillae short, without sediment particles. Large ventral papillae absent.

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Acrocirridae gen. spp.

Remarks

Samples were identified to family level only or individuals were too fragmented for further analysis.

Records

16 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Ampharetidae Malmgren, 1866

T. Alvestad, L. M. Gunton

Ampharetidae are tubicolous annelids, with a body divided into a distinct thorax and abdomen, unlike the closely related Terebellidae, species of Ampharetidae are able to fully retract buccal tentacles into the mouth. The family Ampharetidae is composed of 64 accepted genera and > 300 species (

Amage

Diagnosis

Length 12 mm, width 4 mm. Body short, thick, with a short abdomen. Prostomium complex; central part drawn out into two lateral horns, lateral parts form large lobes while front part forms a ‘lip’. No glandular ridges or eyes. Approximately three pairs of branchiae in a transverse line in two widely separate groups. No paleae. Fourteen thoracic segments with notopodia with chaetae. First three pairs of notopodia and chaetae small. Thoracic uncini from segment VI. Eleven thoracic uncinigers. Nine abdominal uncinigers. Abdomen with rudimentary notopodia. Pygidium without lateral cirri.

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Ampharetidae and Melinnidae. Ampharetidae A Amage sp. nov. 1 B Anobothrus sp. nov. 1, anterior end methyl blue staining C Anobothrus sp. nov. 2 anterior end methyl blue staining. Melinnidae D Melinna cf. armandi and tube (

Amage tasmanensis

Diagnosis

Length 16–30 mm, width 3–5 mm. Widest at branchial region. Thorax long and cylindrical, not tapering towards abdomen. Abdomen short; half length of thorax tapering towards pygidium. Prostomium without glandular ridges or eyes. Distal part of prostomium with longitudinal folds. Ventral surface of buccal segment with longitudinal folds. Four pairs of branchiae arranged as three middle pairs, almost in a transverse line, and one outer pair behind the outermost of the inner branchiae. Right and left branchial group separated by a space more or less equal to width of one branchia. Large lateral lobes on segment II. No paleae. Third segment with rudimentary notopodia with a few extremely small chaetae. Fourth and fifth segment with small notopodia with a few very short chaetae. Sixth to 16th segment with normal sized notopodia and notochaetae. Fourteen thoracic segments with notochaetae. Thoracic uncini from segment VI. Eleven thoracic uncinigers. Approximately 12 abdominal uncinigers. Abdomen with rudimentary notopodia. Pygidium with a pair of lateral cirri with thick bases and slender tips.

Remarks

The holotype of Amage tasmanensis was collected from 3830 m in the Tasman Sea. Due to the matching morphology and close proximity of the specimens from this study to the collection location of the holotype, we assign the name Amage tasmanensis.

Records

29 specimens. Suppl. material

Amphicteis sp. nov.

Diagnosis

Length 20–30 mm, 3 mm at widest section. Paired longitudinal glandular ridges curving slightly sidewise anteriorly. Paired transverse nuchal ridges separated by median gap, ridges at right angle to each other. Buccal tentacles and branchiae missing on both specimens. Chaetae on segment II modified to golden paleae extending past prostomium. Seventeen thoracic chaetigers including paleae, 15 abdominal chaetigers including pygidium. Anal cirri absent.

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Anobothrus

Diagnosis

Length 14 mm, width 1 mm. Prostomium trilobed. Median lobe, narrow and protruding, delimited by deep lateral grooves. Eye spots present. Three pairs of branchiae. Branchiae arranged in transverse row without median gap. Branchiophores fused at base, forming a characteristic and well-marked edge/fold above head. Long filiform paleae. Thorax and abdomen of similar length. Fifteen thoracic segments with notopodia and capillary chaetae. Last 12 chaetigers of thorax with neuropodia and uncini. Notopodia on thoracic unciniger 8 slightly elevated and connected with a ciliated band. Tube a thin layer of secretion loosely incrusted with mud and foraminifera.

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Anobothrus

Diagnosis

Incomplete, 9 mm length, 1 mm width. Specimens not in a good condition. Not possible to discern characters on the prostomium or count segments. Conical prostomium. Long filiform paleae. Space between the two groups of branchiae similar to width of one branchia. Tube a thin layer of secretion loosely incrusted with mud and foraminifera.

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Jugamphicteis galatheae

Diagnosis

Length 25–40 mm, width 2–3 mm. Prostomium with four curved nuchal arches. Body long tapering towards pygidium. Four pairs of branchiae. Paleae present, long golden extend past rim of prostomium. First abdominal segment with dorsal fan with large median notch.

Remarks

The holotype of Jugamphicteis galatheae was collected from Kermadec Trench in the South Pacific Ocean ~ 4500 m; however, paratypes were recovered from both the Kermadec Trench and off the east coast of South Africa between Cape Town and Durban ~ 5000 m. The species is reported to have a wide distribution, which may indicate a species complex. Due to the matching morphology and close proximity of the specimens from this study to collection location of the holotype, we assign the name Jugamphicteis galatheae.

Records

40 specimens. Suppl. material

Ampharetidae gen. spp.

Remarks

Beam trawl specimens were incomplete which does not allow further identification, while Brenke sledge samples were identified to family level.

Records

260 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Amphinomidae Lamarck, 1818

L. M. Gunton, D. Ramos, R. S. Wilson

The family Amphinomidae is characterised by simple calcareous chaetae, in some species these chaetae are very fragile breaking off if touched and causing a burning sensation giving them the common name, ‘fireworms’. The family is divided in to two subfamilies, Archinominae Kudenov, 1991 and Amphinominae Lamarck, 1818 based on the presence of accessory dorsal cirrus in the former and absence in the latter. Currently, there are 23 genera containing 148 valid species (

Bathychloeia cf. sibogae

Diagnosis

Body short, ovate, ~ 8 mm in length. 17–18 chaetigers bearing long (3–44 mm) furcate chaetae. Body pale colour, pair of purple spots dorsal on chaetiger 6, visible under skin. Dark blue-black colouration visible under skin on chaetigers 10–13, dorsal and ventral. Caruncle lobed, extending to chaetiger 3. Branchiae branched, only found on chaetiger 5. Parapodia short, but neuro-and notochaetae well separated, neurochaetae lateral. Notochaetae dorsal (remaining tuft on chaetiger 7). Parapodial cirri on all (?) chaetigers, longer on final five. Chaetae long, bifurcate. No serrations or harpoon chaetae. Neurochaetae shorter than notochaetae. Faint membrane/covering visible over the furcate tips of some chaetae. Pygidium with thick anal cirrus, may be part of a pair.

Remarks

The type locality of Bathychloeia sibogae is in the Banda Sea, Malay Archipelago 1158 m depth.

Records

4 specimens: Suppl. material

Linopherus

Diagnosis

Prostomium divided into two. Posterior portion pentagonal with medial antennae on posterior edge, flanked laterally by the first chaetiger. Anterior section round with antennae and palps reduced to small bumps anterolaterally and laterally respectively. Body small, slightly wider anteriorly and tapering posteriorly. Eyes absent. First chaetiger reduced, not continuous dorsally. Papilliform notopodial postchaetal lobe present throughout. Bipinnate branchiae present on chaetigers 3–5.

Remarks

Linopherus sp. 1 differs from a second species of Linopherus known from the GAB (

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Amphinomidae A Linopherus sp. 1, bipinnate branchiae B Linopherus sp. 1, antennae and palps C Paramphinome cf. australis D Paramphinome cf. australis, hooks E Pareurythoe sp. (

Paramphinome cf. australis

Diagnosis

Body shape elongate ~ 3 mm length. Eyes absent. Prostomium rounded. One or two strongly curved hooks on chaetiger 1 (Fig.

Remarks

A redescription of Paramphinome australis is given in

Records

40 specimens. Suppl. material

Pareurythoe

Diagnosis

Body shape elongate (with parallel sides). Notochaetae in dorsal tufts. Caruncle inconspicuous. Caruncle median ridge absent. Branchiae as tufts from chaetiger 3.

Remarks

Also known from six stations (189–2867 m) in the GAB (

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Amphinomidae gen. spp.

Remarks

Samples identified to family level only as individuals too damaged for further analysis, or juveniles (Fig.

Records

5 specimens. ops. 16, 110 (

Family Aphroditidae Malmgren, 1867

A. Murray, R. S. Wilson

Aphroditidae is a family of scale-worms commonly referred to as ‘sea mice’ due to their hairy appearance. Currently, there are seven genera containing 104 species (

Aphrodita cf. talpa

Diagnosis

Body shape ovate, length less than twice maximum width. Specimens with dorsal felt of fine notochaetae covering and obscuring elytra; 15 pairs elytra, elytral surface with micropapillae. Prostomium rounded, without ocular peduncles, eye pigment absent (may be present), nuchal flaps absent; facial tubercle well-developed, ~ same length as prostomium, papillate. Median antenna long, thin, as long as prostomium, with ceratophore ~ one third the length of style; palps long, minute papillae present. Notochaetae of three kinds: capillary chaetae forming matted dorsal felt; iridescent capillary chaetae projecting laterally; and stout, golden acicular spines with fine tubercles and hairs and with fine curved/hooked tips. Neurochaetae stout, superior tier thicker, brown with pilose margin and smooth slightly curved naked tip, inferior tier similar but golden brown and thinner than upper neurochaetae, with thickly pilose margin and slightly curved naked tips.

Remarks

This species may be undescribed; it differs from Aphrodita talpa Quatrefages, 1866 (described from New Zealand) in having an elongate median antenna, hirsute notochaetae, iridescent capillary notochaetae, and lacking hastate neurochaetae. It has previously been reported from a number of locations around Australia at depths of 17–171 m as Aphrodita talpa by

Records

10 specimens. Suppl. material

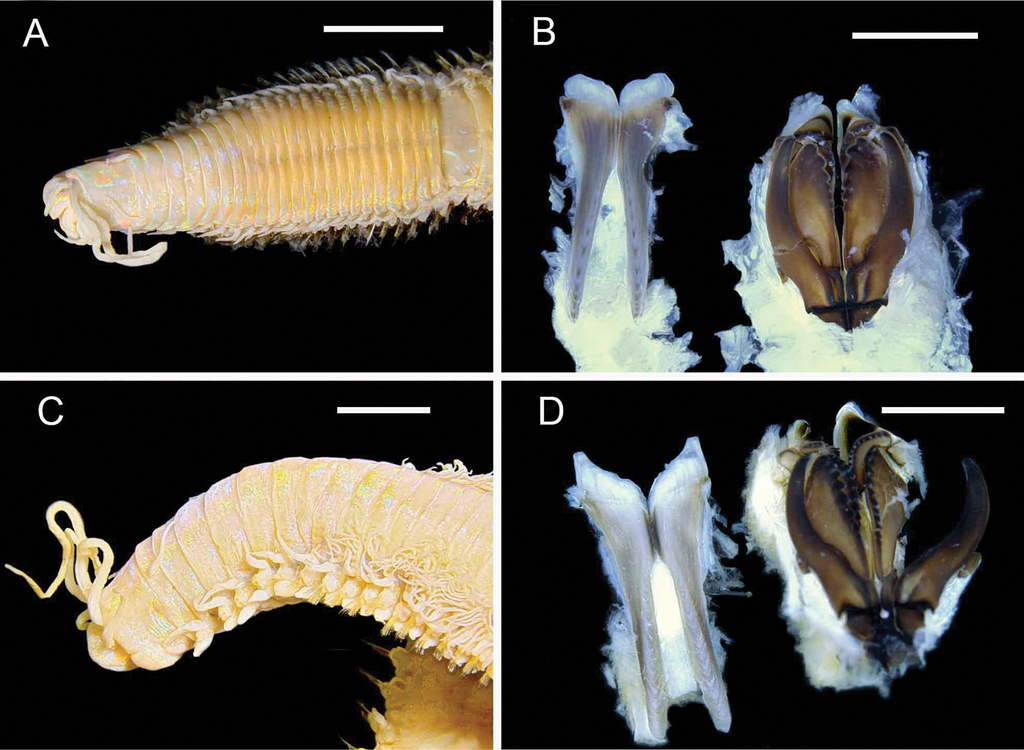

Aphroditidae A Aphrodita cf. talpa (NMV F.293294) dorsal view B Aphrodita cf. talpa (

Aphrodita goolmarris

Diagnosis

Large-bodied specimens, body shape ovate, length less than twice maximum width. Thin dorsal felt of fine notochaetae covering elytra; 15 pairs elytra, elytral surface with micropapillae. Prostomium rounded, without ocular peduncles, with raised ocular areas, pigment absent; facial tubercle well-developed, inflated, with small papillae. Palps extending to segment 11 with minutely papillated margins. Median antenna rod-shaped, fifth length of prostomium. Notochaetae of three kinds: capillary chaetae forming matted dorsal felt; stout, golden-brown, smooth chaetae curving over dorsum; and lateral short tuft of faintly iridescent capillary notochaetae, not forming a fringe. Neuropodia with three tiers of chaetae: stout, superior tier with two stout dark, pilose-tipped acicular neurochaetae, middle tier with 4–9 similar chaetae, inferior tier with 8–15 similar chaetae. Some anterior segments with non-pilose acicular neurochaetae with smooth margins and tips. Numerous golden-yellow, bipinnate neurochaetae present in chaetigers 2 and 3 in inferior position.

Remarks

This species is recorded from Western Australia (WA), New South Wales (NSW) and Queensland (QLD) (Cape York) in depths of 353–3058 m (

Records

4 specimens. Suppl. material

Laetmonice benthaliana

Diagnosis

Body shape elongate, > twice as long as maximum width. Number of chaetigers 33–34. Dorsal felt of fine notochaetae absent. Fifteen pairs of elytra, elytral surface smooth. Elytra comments: some inconspicuous brown pigmented spots in the middle. Prostomium rounded, facial tubercle large and visible dorsally. Facial tubercle papillate. Eye pigmentation absent. Eyes located on elongate ocular peduncles, longer than wide. Median antenna bi-articulate with basal ceratophore and elongate style. Median antenna ceratophore length ~ as long as prostomium. Median antenna ceratostyle length much longer than prostomium (3–6 × as long). Palp surface smooth, palps extending to segment 15. Ventrum with sparse cover of papillae, appearing almost smooth. Ventral cirri of mid-body chaetigers short, not reaching base of neurochaetae. Dorsal notochaetae harpoon-like, with several barb-like tips. Harpoon notochaetae (stout with barbed tips) present. Harpoon notochaetae shaft with fine granulations. Prominent basal spur on neurochaetae present. Spur-neurochaetae of (mid-body segments) subdistal teeth absent. Spur-neurochaetae subdistal hairs present. Marginal hairs not reaching the tip of the spur but leaving a significant basal gap.

Remarks

In this study the species was recorded from 2751–2820 m; other records from the Australian region include RV ‘Dmitry Mendeleev’ voyage 16 stations 1372 and 1373 in the GAB (700–1976 m) by

Records

4 specimens. Suppl. material

Laetmonice yarramba

Diagnosis

Specimens dorsally with debris entangled in felted notochaetae, sometimes obscuring elytra, but dorsal felt not covering elytra, elytra 12–15 pairs. Prostomium with short ocular peduncles, eye pigment absent; facial tubercle well-developed, papillate; nuchal flaps absent. Palps extending to segments 13 and 14, margins finely papillate. Median antenna with ceratophore half length of prostomium; antennal style long thin, > 3 × length of prostomium. Notochaetae of three kinds: golden, curved, smooth, acicular chaetae arched over dorsum; stout, long harpoon chaetae with three recurved fangs below tips, shafts tuberculate on some specimens; tuft of fine mud-covered chaetae ventrally. Neurochaetae in two tiers: superior tier of 2–4 yellow acicular chaetae with basal spur and subdistal fringe of hairs, inferior tier with numerous yellow bipinnate chaetae. Ventrum with small papillae present, or may be absent.

Remarks

Specimens range from 0.2 mm to 7 cm in length. Some individuals are badly damaged, with chaetae missing, and other intact specimens show some morphological variability from the original description by

Records

354 specimens. Suppl. material

Laetmonice cf. producta

Diagnosis

Large-bodied specimen, body shape elongate, > twice as long as maximum width. Dorsal felt of fine notochaetae absent, 18 pairs elytra with purple colouration on inner halves. Prostomium with pair of large ocular peduncles, without eye pigment; facial tubercle well-developed, with long conical papillae; small nuchal flaps present. Palps extending to segment 11, margins finely papillate. Median antenna with ceratophore half the length of the prostomium; antennal ceratostyle longer than prostomium, slender, clavate-tipped, 3 × length of prostomium. Notochaetae of three kinds: ~ 15 smooth, golden, unidentate acicular chaetae; ~ ten long, stout, yellow brown harpoon-like chaetae with 3–5 recurved fangs below tips, shafts smooth or tuberculate; tuft of short, fine mud-covered capillary chaetae ventrally. Neurochaetae in two tiers: superior tier of yellow acicular chaetae with basal spur and subdistal fringe of long hairs and bare tips, inferior tier with numerous golden bipinnate neurochaetae. Ventrum covered with small papillae.

Remarks

This specimen agrees well with the description of other Australian specimens assigned to Laetmonice producta Grube, 1877 by Hutchings & McRae (1993), who stated that the species displayed much morphological variability and had a broad distribution. Grube originally described L. producta from the area of the Kerguelen Islands in the Southern Ocean.

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Family Capitellidae Grube, 1862

L. M. Gunton

Capitellids resemble terrestrial earthworms due to their simple cylindrical body shape, lack of head appendages and often reduced parapodia. The family contains 44 genera and ~ 186 species (

Capitella spp.

Records

7 specimens. Suppl. material

Notomastus spp.

Remarks

A single OTU provisionally referred to Notomastus was recorded from six stations (437–3771 m) in the GAB (

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Capitellidae gen. spp.

Remarks

Specimens not identified beyond family level.

Records

19 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Chaetopteridae Audouin & Milne Edwards, 1833

L. M. Gunton, J. Zhang

Chaetopterids are characterised by a pair of long palps and a body divided into three distinct regions. Some species produce bright blue luminescent mucus. Currently there are five genera and 73 accepted species (

Phyllochaetopterus spp.

Records

7 specimens. Suppl. material

Chaetopteridae gen. spp.

Remarks

The specimens were too fragmented to be identified further.

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Chrysopetalidae Ehlers, 1864

C. Watson

Chrysopetalids are distinguished by broad notochaetal, leaf-like paleae and/or notochaetal spines in fans covering the dorsum. Chrysopetalidae currently contains 29 genera and ~ 110 species (

Dysponetus cf. caecus

Diagnosis

Prostomium truncate, with three short antennae and two short palps. No eyes. Large mouth cirrus and pair of rod-like stylets. Two pairs of cirriform tentacular cirri on segments 1 and 2; segments one and two fused; dorsal cirri segment 1 very long, notopodia 2 with notochaetae. Mid-body notopodia with two lengths of semi-erect, golden-coloured notochaetal fascicles: short, broad and long, slender, spines with two rows of spinelets; elongate cirrophores and long dorsal styles. Neuropodia with fascicle of very slender falcigerous neurochaetae with very long shafts; ventral cirri longer than neuropodia.

Remarks

Similar to, but differs from abyssal East Atlantic Dysponetus cf. caecus (sensu

Records

48 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Cirratulidae Ryckholt, 1851

J. A. Blake

Cirratulids possess many anterior tentacular filaments and numerous long filamentous branchiae along their body which gives them a frilly appearance. Currently there are 11 genera and ~ 277 accepted species (

Cirratulids are divided into (1) bitentaculate genera, having a narrow head consisting of a distinct prostomium and peristomium, a pair of long dorsal tentacles and branchiae along most of the body, and (2) multitentaculate genera having a wedge-shaped head and numerous dorsal tentacles arising from anterior segments (

Aphelochaeta spp. nov.

Remarks

At least three new species of Aphelochaeta are present among these samples. Four OTUs of the genus Aphelochaeta were recorded from the GAB (189–2867 m) (

Records

16 specimens. Suppl. material

Chaetocirratulus sp. nov.

Remarks

A single specimen, believed to be a new species, is similar to Chaetocirratulus pinguis (Hartman, 1978) from Weddell Sea, Antarctica re-described by

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Chaetozone spp. nov.

Remarks

One distinct new species is similar to Chaetozone brunnea described by

Records

13 specimens. Suppl. material

Kirkegaardia sp. nov.

Remarks

At least one new species of Kirkegaardia is present. The specimens have a long smooth peristomium, typical of several species of this genus (

Records

3 specimens. Suppl. material

Cirratulidae gen. spp.

Remarks

Brenke sledge samples were identified to family level.

Records

7 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Dorvilleidae Chamberlin, 1919

H. Wiklund

Dorvilleids contain some of the smallest described annelids and are the only extant group with ctenognath jaws. The family Dorvilleidae consists of ~ 200 species arranged in 32 genera (

Remarks. Species were preliminary separated on the basis of the forms of mandibles, shape of head and appendages, and shape of chaetae. The species vary slightly in size, with the smallest species being just 1 mm long (Ophryotrocha sp. 2) and the largest being 3.2 mm long (Ophryotrocha sp. 5).

Ophryotrocha

Ophryotrocha

Records

137 specimens. Suppl. material

Ophryotrocha

Records

136 specimens. Suppl. material

Ophryotrocha

Records

29 specimens. Suppl. material

Ophryotrocha

Records

17 specimens. Suppl. material

Ophryotrocha

Records

17 specimens. Suppl. material

Ophryotrocha

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Ophryotrocha

Records

3 specimens. Suppl. material

Dorvilleidae gen. spp.

Remarks

Specimens from whale fall (op. 100) were too damaged or dried out to be identified. A single specimen provisionally referred to Schistomeringos was recorded from 932 m in the GAB (

Records

75 specimens. Table

Family Eunicidae Berthold, 1827

R. S. Wilson

Along with other members of the order Eunicida, species of Eunicidae possess a ventral muscular pharynx with mineralized or sclerotized jaws. Eunicidae are recognisable by possessing a prostomium with one to three antennae which lack ringed ceratophores. The family consists of 11 extant genera and 453 currently accepted species (

Eunice sp. nov.

Diagnosis

No pigmentation on preserved specimens. Prostomium bilobed, slightly notched. Eyes present, behind bases of palps. Prostomial appendages with widest gap separating palps from lateral antennae. Palpostyles, antennal styles, and peristomial cirri with irregular articulations. Peristomial rings distinct dorsally and ventrally but continuous laterally. Maxillae dentition: Mx I left 1, right 1. Mx II left 7, right 6. Mx III left 6. Mx IV left 5, right 9. Mx V left 1, right 1.

Branchiae absent. Lateral black dot between posterior parapodia absent. Dorsal cirri length short, at most as long as two body segments. Dorsal cirri of anterior chaetigers tapering, median chaetigers tapering, posterior chaetigers tapering, smooth, without articulations. Digitiform ventral cirri, basally inflated, commence chaetiger 3.

Pectinate chaetae absent. Compound falcigers present, appendages distally bidentate, hoods without mucros (rounded). Compound spinigers absent. Aciculae dark honey-coloured to black, distally bluntly pointed. Subacicular hooks dark honey-coloured to black, bidentate, distal tooth directed distally, subdistal tooth directed laterally. Subacicular hooks first present from chaetiger 24–27.

Remarks

Although referred to here as ‘Eunice sp.’, the above combination of characters cannot be accommodated in any currently known eunicid genus. The species is here treated as a member of Eunice since that genus remains poorly defined and already contains species of uncertain relationships (

Leodice sp. nov.

Diagnosis

Prostomial lobes frontally rounded, bilobed, slightly notched. Eyes behind bases of palps. Prostomial appendages evenly spaced, with palps slightly thinner than antennae. Antennal styles and palpostyles without articulations. Peristomial rings distinct dorsally and ventrally, continuous laterally. Peristomial (tentacular) cirri present, reach anterior region of peristomium, styles tapering, without articulations.

Maxillae dentition: Mx I left 1, right 1. Mx II left 7, right 9. Mx III left 12 (right absent). Mx IV left 6, right 11. Mx V left 1, right 1.

Branchiae present from chaetiger 4. Branchiae distinctly longer than dorsal cirri. Maximum number of branchial filaments 12–13 (at ~ chaetiger 10–12); five or six anterior chaetigers with single branchial filaments, no posterior chaetigers with single branchial filaments. Branchiae continuing until chaetiger 32–34. Ventral cirri of anterior segments digitiform.

Compound falcigers present, appendages bidentate, hoods without mucros (rounded). Aciculae light yellow, translucent. Subacicular hooks colour light yellow, translucent, bidentate.

Variation

A number of very small specimens (< ~ 1.5 mm maximum width) differ from the above description in having at most three or four branchial filaments, and a single specimen much larger than the remaining material has < 18 branchial filaments. These specimens apparently do not differ in other respects and all are assumed to represent a single species.

Remarks

This species clearly belongs in the genus Leodice following the generic concept of

Records

28 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Euphrosinidae Williams, 1852

D. Ramos

Euphrosinidae have short, wide bodies bearing many chaetae. There are ~ 62 species in four genera now considered valid (

Euphrosinopsis cf. horsti

Diagnosis

Narrow prostomium, flanked by first three chaetigers, with a broader ventral pad. Pair of large eyes dorsally. Oval body dorsoventrally flattened. Abundant chaetae densely covering the dorsum. Notochaetae in five tiers: first and fifth tiers with small furcate chaetae, second and fourth tiers with large furcate chaetae, and third tier with category IIB ringent chaetae. Neurochaetae furcate. Paired inflated anal cirri with unfused bases present.

Remarks

Observed specimens differ from described Euphrosinopsis species in having five tiers of notochaetae instead of two in E. antarctica, three in E. crassiseta, and four in E. horsti (

Records

3 specimens. Suppl. material

Euphrosinidae

Records

1 specimen. op. 9 (

Family Fabriciidae Rioja, 1923

A. Murray

Fabriciids are small (0.85–10 mm long) fanworms. Approximately 80 species in 17 valid genera are now considered to be in the family Fabriciidae (

Fabriciidae

Diagnosis

One small complete specimen, ~ 2 mm long. Branchial crown with three pairs of radioles with long pinnules terminating at same height as radioles. Eight thoracic and three abdominal chaetigers. Peristomial collar low, membranous, entire ventrally, mid-dorsally incised, anterior margin with shallow lateral notches (ventral conical flap or lobe absent). Dorsal lips as low rounded structures, ventral filamentous appendages absent. Conical structure above mouth absent. Peristomial glandular patches present. All thoracic notochaetae of two lengths: superior elongate, narrowly hooded; inferior short, narrowly hooded. Notochaetae of segments 3–8 similar to those of 1 and 2, pseudospatulate notochaetae absent. Thoracic uncini acicular with few rows of similar-sized teeth above main fang, hood present. Abdominal uncini with rasp-shaped teeth and long manubrium. Pigmented pygidial eyespots absent.

Remarks

This single specimen has been preserved in 95% ethanol and may have lost pigmentation of the peristomial and pygidial eyes. There are many similarities with the genus Fabriciola but the absence of ventral filamentous appendages is not typical for that genus, so the identification is tentative. More complete and well-preserved specimens would be required to provide a positive identification. This specimen also does not match the diagnosis for Pseudofabriciola, with which it is also similar. This specimen is also similar to that found in the deep GAB surveys of 2015 and 2017, recorded as ‘? Fabriciola sp.’ (

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Fabriciidae

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Family Fauveliopsidae Hartman, 1971

A. Murray, D. Ramos

Fauveliopsids may be cylindrical or have swellings along the body, they can be free-living or occupy gastropod shells, foraminifera tests, or tubes (

Fauveliopsis cf. challengeriae

Diagnosis

Specimens complete, 14.5 mm long, 1.5 mm wide at widest point. Body integument rugose and opaque, with scattered small papillae, tapered, posteriorly swollen, with segments in posterior region short (2–4 × wider than long), and 33 chaetigers. Anterior chaetigers with 2–4 chaetae per ramus, capillary and acicular (sigmoid or falcate) chaetae; middle and posterior chaetigers with 2–3 chaetae per notopodium and 3–5 chaetae per neuropodium, including falcate acicular chaetae and capillary chaetae. Interramal papillae distinct, somewhat stalked. Genital papillae not seen. Living in cemented sediment foraminifera tubes.

Remarks

The type locality for this species is in the Southern Ocean between Antarctica and Australia in 3510 m depth. It has not previously been recorded in Australian waters, but was recently redescribed from specimens from Antarctic waters and Eastern Pacific Ocean (

Records

3 specimens. Suppl. material

Laubieriopsis hartmanae

Diagnosis

Prostomium retracted. Body linear, blunt on both ends with 16 chaetigers. Chaetigers 1–4 shorter with 2–3 large acicular chaetae and 2–3 small acicular chaetae per parapodia. Chaetigers 5–16 with one acicular and one capillary per ramus, longest on chaetiger 16. Granular genital papillae on boundary of chaetigers 6 and 7.

Remarks

Similar in appearance to L. brevis from the Atlantic Ocean, but differs in the tips of the aciculars (bidentate in L. brevis) and genital papilla (smooth in L. brevis) (

Records

22 specimens. Suppl. material

Riseriopsis cf. santosae

Diagnosis

Prostomium retracted. Body linear with annulations, slightly inflated terminally with 27 chaetigers. Chaetigers 1–3 shorter, parapodia with one acicular and one capillary per ramus and an interramal papillae. Following chaetigers with one acicular and one capillary in the neuropodia and one larger acicular in the notopodia.

Remarks

Riseriopsis santosae resembles this specimen but differs in having more chaetigers (37–88). Riseriopsis santosae is known from shallower depths (410–415 m), while the only described deep-sea species in the genus, R. confusa (Thiel, Purschke & Böggemann, 2011), has a similar number of chaetigers as this specimen, but with an acicular and capillary in the medial notopodia. Both of these species are recorded from the South Atlantic.

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Fauveliopsidae gen. spp.

Remarks

Brenke sledge samples identified to family level.

Records

60 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Flabelligeridae de Saint-Joseph, 1894

N. Jimi

The family Flabelligeridae is a group of sedentary annelids living in soft sediments or on hard substrates, except for two pelagic genera (

Bradabyssa cf. kirkegaardi

Diagnosis

Length 3 mm, width 0.5 mm, body papillae very long, thin, abundant. Cephalic cage not developed. One capillary notochaeta, one anchylosed neurochaeta. Sediment particles present on base of papillae.

Remarks

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Flabelligeridae A Bradabyssa cf. kirkegaardi (

Bradabyssa

Diagnosis

Incomplete, length 9 mm, width 1 mm, 26 chaetigers, body papillae long, thin, abundant, with mud. Cephalic cage not developed. 2–4 capillary notochaetae, 3–4 anchylosed neurochaetae. Sediment particles present on body surface.

Remarks

This species belongs to group ‘villosa’ described in

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Bradabyssa

Diagnosis

Incomplete, length 25 mm, width 3 mm, 28 chaetigers, body tubercles short, without sediment particles, abundant. Cephalic cage not developed. 4–5 capillary notochaetae, 3–4 anchylosed neurochaetae. Sediment particles present on body surface.

Remarks

This species belongs to group ‘verrucosa’ described in

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Diplocirrus

Diagnosis

Incomplete, length 5.4 mm, width 1 mm, 16 chaetigers. Body with first ten chaetigers swollen, thereafter cylindrical. Cephalic cage (chaetiger 1) developed. Lateral papillae and chaetae well developed in posterior chaetigers. Sand particles restricted on body wall. Body papillae few, short, thin.

Records

7 specimens. Suppl. material

Diplocirrus

Diagnosis

Incomplete, length ~ 5–8 mm, width 1 mm, ~ 17 chaetigers. Body with first nine chaetigers swollen, thereafter cylindrical. Cephalic cage (chaetigers 1 and 2) developed. Lateral papillae and chaetae well developed in posterior chaetigers. Sand particles on body wall, absent on body papillae. Body papillae abundant, short, thin.

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Diplocirrus

Diagnosis

Incomplete. Length 4 mm, width 0.5 mm, ~ 16 chaetigers. Body with first eight chaetigers swollen, thereafter cylindrical. Cephalic cage (chaetigers 1–3) developed. Lateral papillae not developed in posterior chaetigers, chaetae developed in posterior chaetigers. Attached sand particles absent. Body papillae scarce, very short, thin.

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Diplocirrus

Diagnosis

Incomplete. Length 5 mm, width 1.5 mm, ~ 13 chaetigers. Body with first eight chaetigers swollen, thereafter cylindrical. Cephalic cage (chaetigers 1–4) developed. Lateral papillae not developed in posterior chaetigers, chaetae developed along entire body. Sand particles present on body surface. Body papillae abundant, very short, thin, without sand particles.

Records

5 specimens. Suppl. material

Diplocirrus

Diagnosis

Incomplete, only anterior fragments. Cephalic cage (chaetiger 1) developed. Large sand particles present on body surface. Body papillae few, short, thin, with large sediment particles on the base.

Records

3 specimens. Suppl. material

Ilyphagus

Diagnosis

Incomplete, damaged. Only anterior chaetigers. Body papillae very long, thin, abundant, with sediment particles at base of papillae. Cephalic cage developed. 1–2 capillary notochaetae, 4–5 anchylosed neurochaetae.

Records

4 specimens. Suppl. material

Flabelligeridae gen. spp.

Remarks

Specimens were too damaged to identify further and Brenke sledge samples were identified only to family level.

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Family Glyceridae Grube, 1850

M. Böggemann, R. Sobczyk

Cylindrical and long-bodied worms, widely distributed in soft bottom sediments from intertidal zone to abyssal depths (

Glycera cf. capitata

Diagnosis

Specimens < 7 mm long, 1.2 mm wide. Prostomium with ~ ten rings. Parapodia of mid-body with longer neuropodial than notopodial prechaetal lobes and one rounded postchaetal lobe, dorsal cirri inserted on body wall far above parapodial base. Proboscideal papillae of two types, long digitiform (Fig.

Remarks

The identification to species level is tentative because the type locality of Glycera capitata is in the Atlantic Ocean off Greenland and there are no molecular data.

Records

4 specimens. Suppl. material

Glyceridae and Goniadidae. A Glyceridae, Glycera sp. anterior body with everted pharynx, ventrolateral view (

Glycera cf. russa

Diagnosis

Specimen 74 mm long, 6 mm wide. Prostomium with only nine rings. Postchaetal lobes of mid-parapodia both triangular and similar in length along most of the body, posteriorly more acute. Proboscideal papillae of two types, long conical ones (Fig.

Remarks

This specimen most resembles Glycera russa Grube, 1870. However, the prostomium consists of nine rings and the proboscideal papillae have only up to ten ridges, therefore, this may be a new species.

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Glycera spp.

Diagnosis

Specimens with various lengths of the body and number of segments. Specimens dried up or missing the anterior parts of body. Prostomium when present prolonged, distinctly annulated with two pairs of appendages situated on anterior margin; eyes absent. Cylindrical proboscis, if present, covered by papillae; terminal part with four ailerons. Parapodia biramous.

Records

4 specimens. Suppl. material

Glyceridae gen. spp.

Remarks

Brenke sledge samples were identified to family level.

In addition to the taxa recorded from this study, Glycera lapidum Quatrefages, 1866 (13 stations, 212–2063 m) and Glycerella magellanica (McIntosh, 1885) (a single specimen, 2503 m) were recorded from the GAB (

Records

17 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Goniadidae Kinberg, 1865

M. Böggemann, R. Sobczyk

As the sister group to glycerids, goniadids are cylindrical, long-bodied annelids. The family is easily distinguished from glycerids by presence of usually one pair of macrognaths and variable number of ventral and dorsal micrognaths instead of two pairs of jaws on the anterior end of pharynx (

Bathyglycinde profunda

Diagnosis

Up to 24 mm length and 69 segments; anterior 36–37 parapodia uniramous; prostomium indistinctly annulated with bi-articulated terminal appendages; eyes absent; chevrons not present; papillae on pharynx arranged in rows (Fig.

Remarks

A Depth range of 350–5500 m has been reported (

Records

7 specimens. Suppl. material

Goniadidae gen. spp.

Remarks

Brenke sledge samples were identified to family level. Goniada antipoda (a single specimen, 2366 m), Progoniada regularis (a single specimen, 1486 m) and Progoniada sp. MoV7077 (5 stations, 932–4068 m) were recorded from the GAB (

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Family Hesionidae Grube, 1850

C.J. Glasby, D. Ramos

Hesionids are a reasonably common and widespread group of polychaetes that have affinities with other nereidiforms, especially nereidids and syllids (

Microphthalmus

Diagnosis

Prostomium round, anteriorly cleft, broader than long, with three antennae and two palps. Antennae twice the length of the palps. No eyes. Six pairs of cirriform tentacular cirri on segments 1–3, longer than dorsal cirri. Uniramous parapodia. Dorsal cirri shorter on segment 4 than those on segment 5 onwards. Neuropodia with a pointed prechaetal lobe longer than the blunt postchaetal lobe. Neurochaetae heterogomph falcigers with serrated edge. Pygidium with two anal cirri and a ventral anal plate. Colour in ethanol pale yellow.

Records

10 specimens. Suppl. material

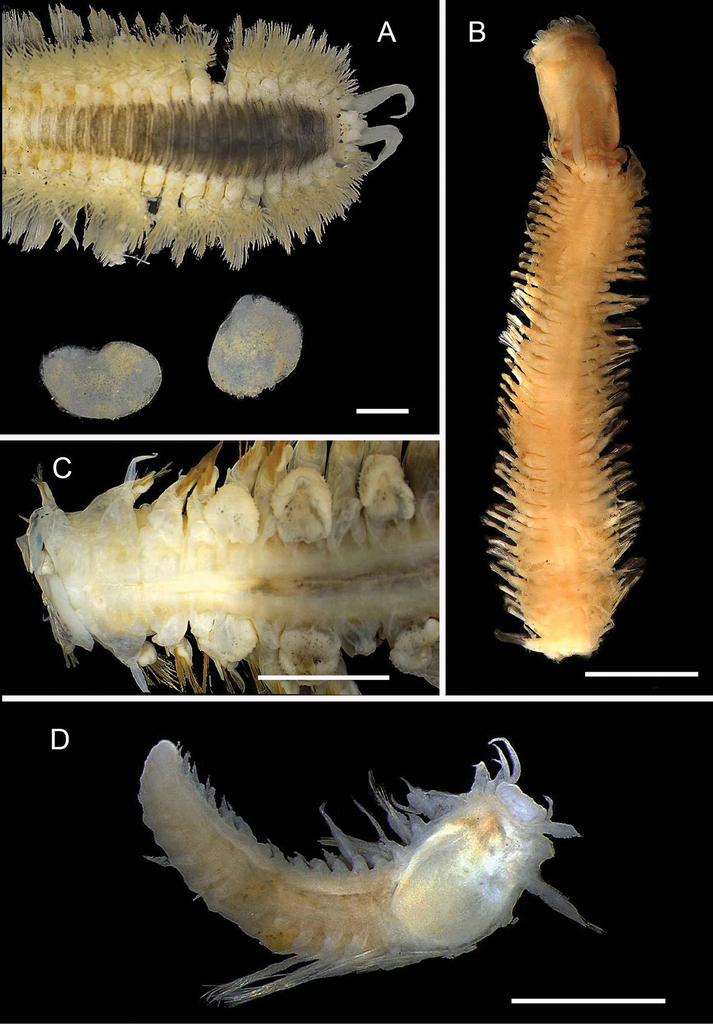

Hesionidae A Microphthalmus sp. B Microphthalmus sp., anterior end C Microphthalmus sp., pygidium D Neogyptis sp. nov. 1 (

Neogyptis

Diagnosis

Specimens all incomplete. Prostomium subrectangular (broader than long), posteriorly with deep mid-dorsal incision; one pair lateral antennae, tips well defined, extending two thirds to just short of length of palps; one short mid-prostomial antenna. Eyespots not visible. Palps bi-articulate, palpostyle cylindrical, twice length palpophore. Proboscis with many cylindrical papillae two or three rows deep, each papilla cilia-tipped. Nuchal organs very conspicuous, light brown, extending from anterolateral prostomium and coalescing mid-posterodorsally. First four segments tentacular, achaetous, bearing eight pairs tentacular cirri, longest extending back to chaetigers 5 or 6. Parapodia biramous throughout, dorsal cirri slender tapered, ~ two thirds length parapodial lobes anteriorly, half length in mid body; ventral cirri slender distally attached, tapered, extending less than half length parapodial lobes. Notopodia bearing capillaries only. Neuropodia compound spinigers. Colour in ethanol yellow-white base, with dark brown band dorsally and laterally on all tentacular segments, and lighter brown nuchal organs.

Remarks

The present material clearly falls within the concept of the tribe Amphidurini Pleijel, Rouse, Sundkvist & Nygren, 2012, which includes Amphiduros Hartman, 1959, Amphiduropsis Pleijel, 2001, Neogyptis Pleijel, Rouse, Sundkvist & Nygren, 2012, and questionably Parahesione Pettibone, 1956. Of these three genera the present specimens are closest to Neogyptis because of the terminal ring of proboscideal papillae and presence of a median antenna. The fine-tipped lateral cirri and cilia-tipped cylindrical papillae were clearly visible only in the formalin-fixed specimen (

Of the 12 species in the genus the only species currently known from the West Pacific is Neogyptis hinehina Pleijel, Rouse, Sundkvist & Nygren, 2012 from the Lau Basin, south of Tonga. However, this species has twisted noto- and neurochaetae, which were not observed in the present material. Therefore, the present material probably represents an undescribed species.

Records

11 specimens. Suppl. material

Neogyptis

Diagnosis

Specimens incomplete. Prostomium subrectangular (broader than long), posteriorly with slight mid-dorsal incision; antennae, presence implied from scars as follows: two lateral and one median antenna situated mid-posteriorly. Eyespots not visible. Palps bi-articulate, palpostyle cylindrical to conical, approximately equal in length to palpophore. Everted proboscis with many cushion-shaped distal papillae. First four segments tentacular, achaetous, bearing eight pairs tentacular cirri, slightly shorter than dorsal cirri of chaetiger 1. Nuchal organs, unpigmented, coalescing mid-dorsally. Parapodia biramous throughout, dorsal cirri slender tapered, ~ equal in length to parapodial lobes, except those on first chaetiger which are many times longer than parapodial lobe; ventral cirri distally attached, slender tapered, ~ half-length parapodial lobes throughout. Notopodia bearing serrated capillaries and one or two smooth spines. Neurochaetae all compound spinigers. Colour in ethanol yellow-white, unpigmented.

Remarks

See above for discussion justifying placement of this material into Neogyptis, tribe Amphidurini Pleijel, Rouse, Sundkvist & Nygren, 2012, and reasons for considering it represents an undescribed species. Neogyptis sp. 2 differs from Neogyptis sp. 1 in having palpostyles approximately equal in length to the palpophore, and lacking brown pigmentation on tentacular segments and the nuchal organs.

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Parahesiocaeca

Diagnosis

Specimens in poor condition, incomplete. Prostomium sub-rectangular, with three antennae, all tapering rapidly and broader at base, extending just beyond tip of palps. Bi-articulated palps, palpostyle cylindrical. Eyes absent. Proboscis with marginal papillae. First two segments tentacular, achaetous, bearing four pairs of tentacular cirri (inferred from stubs). Tentacular and dorsal cirri appearing to be articulated. Parapodia sub-biramous. Neuropodia with long prechaetal lobe, short postchaetal lobe, and short ventral cirrus; all neurochaetae with long-bladed heterogomph falcigers with very fine tips.

Remarks

The present specimens fit the description of the genus Parahesiocaeca Uchida, 2004, although it differs from the description of the only species, P. japonica Uchida, 2004, in lacking eyes, having brown-pigmented nuchal organs, and the heterogomph falcigers having very long blades with very fine tips. The specimens probably represent an undescribed species, but their condition is too poor to describe as a new species.

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Pleijelius cf. longae

Diagnosis

Prostomium ovoid, broader than long, with three short antennae and two short palps. No eyes. Six pairs of cirriform tentacular cirri on segments 1–3, longer than dorsal cirri. Dorsal cirri from segment 4 onwards multiarticulate, longer than body width. Notopodia low mounds with notochaetae spread out in a fan-like arrangement dorsally. Neuropodia elongated, with straight acicula and long acicular lobes. Neurochaetae heterogomph falcigers with serrated edge. Ventral cirri cirriform, much smaller than dorsal cirri. Three cirriform anal cirri on pygidium. Colour in ethanol white.

Remarks

We use the cf. designation here in recognition that Pleijelius longae, the only representative of the genus and originally described from the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean at 3500 m, is unlikely to be the same species as ours. Pleijelius is represented by a single species, P. longae Salazar-Vallejo & Orensanz, 2006. Observed specimens differ from P. longae in having notochaetal capillaries with denticles along the entire length instead of just near the tip, as well as possessing three anal cirri instead of six. This is the first report of this genus in the Pacific Ocean, occurring on whale fall, and at a depth of 1000 m.

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Vrijenhoekia ketea

Diagnosis

Prostomium rectangular, with two lateral antennae, a very small median antenna, two palps, and a facial tubercle. Palpophores thicker than palpostyles, similar lengths. No eyes. Everted proboscis lacking papilla. Three fused anterior segments. Parapodia uniramous. Dorsal cirri long, especially in segments 1–5. Ventral cirri the same length as neuropodia after segments 1–3, digitiform, and inserted subterminally. Colour in ethanol pale yellow.

Remarks

The specimen differs from other specimens of the V. ketea species complex in having a larger body, being closer to the size range observed for V. balaenophila (

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Vrijenhoekia

Diagnosis

Two complete specimens, 22 chaetigers (i.e., appears to be fixed growth of maximum 22 chaetigers). Prostomium subrectangular (broader than long), one pair lateral antennae, long, tapered, extending to tip of palps or 2 × longer; median antenna absent. Small red eyespots present, two or three pairs. Palps bi-articulate, palpostyle oval to globulose, slightly longer than palpophore. Proboscis with ten digitate terminal papillae and micro-papillae on surface; jaws absent. Facial tubercle absent. First three segments tentacular, achaetous, bearing six pairs tentacular cirri, slender, longest almost half length of body. Parapodia uniramous throughout, bearing digitate prechaetal lobe; dorsal and ventral cirri slender, tapered, similar in length throughout: ~ 0.5–1 × length of parapodial lobes, except for first and second pairs which are many times longer than parapodial lobe (similar in length to tentacular cirri). Ventral cirri inserted subterminally. Fan-like supra- and sub-neuropodial fascicles, bearing compound spinigers only, all with similar-length blades. Colour in ethanol yellow-white, unpigmented.

Remarks

The present specimens are closer to Vrijenhoekia than any other described hesionid genus, but differ from its type species, Vrijenhoekia balaenophila, and from V. cf. ketea as described above, as follows: a mediodorsal prostomial process (tubercle or antenna) was not observed (present in other members of the genus though minute and probably only observable clearly with scanning electron microscopy); palpostyles are globulose in the present material vs. tapered; compound chaetae blades are relatively longer in the present material; and the present specimens appear to have a maximum of 22 chaetigers, whereas there are 35 in the type species (this character is not reported in other species of the genus). On the other hand, the present material resembles more closely the type species than V. cf. ketea in having ten digitate proboscideal papillae (absent in the latter). The globulose (= ovoid) palpostyles are the most distinctive feature of the species.

Records

13 specimens. Suppl. material

Hesionidae gen. spp.

Remarks

Twelve specimens of Hesionidae could not be identified beyond family because key features were lacking or the specimens were damaged (missing posterior segments, tentacles, antennae etc.).

Material provisionally referred to Leocrates cf. chinensis (four stations, 987–1402 m), Hesiolyra sp. (one specimen, 996 m), Nereimyra sp. (one specimen, 1256 m), and Parahesione sp. MoV6858 (three stations, 203–236 m) was recorded from the GAB (

Records

11 specimens. Suppl. material

Family Lacydoniidae Bergström, 1914

A. Murray

Lacydoniidae are an uncommon, but widespread group of polychaetes that have affinities with phyllodocids (

Lacydonia cf. laureci

Diagnosis

Specimen incomplete, ~ 2 mm wide excluding chaetae, 3 mm long for head plus 12 anterior segments. Body dorsoventrally flattened. Prostomium approximately as wide as long, somewhat indented anteriorly, with conspicuous lateral lobes present on posterior margin of prostomium, giving the appearance of a much wider than long prostomium. Eyes absent, median antenna missing. Pair of short digitiform to filiform lateral antennae located in slight incisions mid-prostomium; pair of similar-sized/shaped palps arising ventral to prostomial anterior margin. Faded pale brown pigment present on prostomium, dorsally and ventrally, and dorsally as transverse bands on tentacular segment and some other segments, and as spots on dorsal cirri and parapodia. Tentacular segment short, achaetous, with pair of ventrolateral cirri. Chaetigers 1–3 uniramous, with compound spinigerous chaetae, subsequent parapodia biramous, rami elongate and widely separated, with elongate supracicular lobes. Notochaetae simple capillary chaetae, finely spinulose distally; neurochaetae compound spinigers with heterogomph shaft-heads and long, finely spinulose blades. Dorsal cirri short, thick, digitiform, glandular, inserted basally on first three chaetigers, thereafter medially to distally on notopodia. Ventral cirri of similar size and shape, inserted distally on neuropodia. Posterior segments, pygidium and pygidial cirri, all missing and therefore unknown.

Remarks

Lacydonia laureci Laubier, 1975 is the only currently described species that possesses conspicuous lateral lobes on the posterior margin of the prostomium. This specimen bears some similarity to L. laureci, because of these lobes, as well as the absence of eyes, but there are a few differences also apparent:

Records

1 specimen (incomplete). Suppl. material

Family Lumbrineridae Schmarda, 1861

P. Borisova, N. Budaeva, D. Ramos

Lumbrineridae is a family of jaw-bearing annelids from the large monophyletic group Eunicida. Lumbrinerids have a simple external morphology, with uniform elongated body, simple uniramous parapodia, and conical prostomium lacking distinct appendages or eyes. No appendages are present on the peristomium consisting of two rings, and only few species have branchiae associated with parapodia. In contrast, the diversity of jaw morphology is remarkable, and morphology of maxillary plates is used as diagnostic characters at genus and species levels. The family comprises 19 genera and ~ 300 species and has world-wide distribution (

Cenogenus sp. nov.

Diagnosis

Body width: 1–2 mm. Prostomium conical, elongated, shorter than peristomium. Nuchal antenna not observed. All parapodia well developed, first four pairs of parapodia smaller than remaining parapodia. Parapodia with inconspicuous prechaetal and postchaetal lobes equal in size. Anterior parapodia with simple digitate elongate (length to width ratio near 2:3) branchia attached dorsally and posteriorly to parapodial lobes, in middle parapodia branchiae decrease in length becoming more rounded.

Anterior parapodia with long fragile limbate chaetae only, middle parapodia with limbate chaetae and simple multidentate hooded hooks with six to seven small teeth and long blade. All chaetae dark, black or dark brown in colour, becoming translucent near tip. Acicula dark, two in median parapodia.

Maxillary apparatus dark, stout, with four pairs of maxillae. Maxillary carriers shorter than MI. MI forceps-like with attachment lamellae, without connecting plates. MII as long as MI, with two large teeth. MIII unidentate, completely pigmented, dark in colour. MIV large, unidentate round-square plates, completely pigmented.

Remarks

The specimen

Records

4 specimens. Suppl. material

Lumbrineridae A Cenogenus sp. nov. (

Eranno sp. nov.

Diagnosis

Prostomium conical, as long as wide, shorter than peristomium. Nuchal antenna absent. All parapodia well developed, first four to five pairs of parapodia smaller than remaining parapodia. Prechaetal lobes inconspicuous in all parapodia, postchaetal lobes auricular in anterior parapodia (1–40), becoming small and rounded posteriorly, always longer than prechaetal lobes.

Anterior parapodia with limbate chaetae and limbate simple hooded hooks. Clear simple multidentate hooded hooks present after chaetiger 25, with seven to eight teeth and long blades, all of similar size. In median chaetigers (27–40) part of limbate chaetae exceedingly longer than in the remaining chaetigers and ~ twice as long as hooded hooks.

Maxillary apparatus dark, with five pairs of maxillae, elongated. Maxillary carriers shorter than MI. MI forceps-like with attachment lamellae, with narrow connecting plates. MII shorter than MI, with five teeth. MIII unidentate, completely pigmented, dark in colour. MIV unidentate, large, completely pigmented. MV reduced to attachment lamella, partly fused with MIV.

Remarks

Limbate simple hooded hooks are not typical for Eranno and similar to those reported for Abyssoninoe, however, maxillary apparatus is of typical Eranno shape with narrow connecting plates and MII significantly shorter than MI. There is not enough information to consider this a new genus, but we suggest it is a new species.

Records

1 specimen. Suppl. material

Lumbrineris

Diagnosis

Bluntly conical prostomium without appendages. Two peristomial rings of similar sizes. Parapodia uniramous, neuropodia bearing yellow acicula, limbate chaetae compound (until chaetiger 13) and simple (chaetiger 14 onwards) hooded hooks with up to nine teeth. Maxillary apparatus: MII quadridentate, almost as long as MI; MIII and MIV unidentate. Colour in ethanol pale yellow.

Records

1 specimen. op. 4 (

Lumbrineridae gen. spp.

Remarks

Brenke sledge samples were identified to family level.

Records

5 specimens: Suppl. material

Family Maldanidae Malmgren, 1867

J.A. Kongsrud

The family Maldanidae, commonly known as bamboo worms, are infaunal burrowers inhabiting tubes made of sediments consolidated by mucus. The family comprises ~ 240 valid species in 38 genera and five subfamilies (

Boguea sp. nov.

Diagnosis

Complete specimens with ~ 30 chaetigers, < 20 mm long and 0.2 mm wide. Head rounded without a cephalic plate. Cephalic keel well developed. Nuchal slits curved, parallel on each side of the cephalic keel. Neuropodia with avicular uncini present from chaetiger 5. Avicular uncini in single row in chaetiger 5–8, in double rows from chaetiger 9 and onwards. Pygidium simple, without papillae. Anus terminal. Tube cylindrical, straight, thick and solid, consisting of a thin inner organic layer incrusted with a thick layer of densely packed mud. Ventral glandular pads on anterior part of chaetigers 4–6 with reddish-brown pigmentation.

Remarks

At present, only two species of Boguea have been described, B. enigmatica Hartman, 1945 from North Carolina, USA and B. panwaensis Meyer & Westheide, 1997 from Phuket, Thailand. This is the first record of the genus in the deep sea.

Records

10 specimens. Suppl. material

Chirimia sp. nov.

Diagnosis

Largest specimen available, anterior fragment with 14 chaetigers, 43 mm long and 3 mm wide. Head with cephalic plate bordered with well-developed rim. Cephalic rim divided in lateral and posterior lobes by deep lateral incisions; lateral lobes with five elongated, triangular cirri. Posterior lobe with eight triangular cirri. Nuchal slits long, U-shaped. No visible cephalic keel between nuchal slits. Palpode wide, rounded. Chaetiger 1 with distinct collar with deep lateral notches. Neurochaeta as rostrate hooks, starting on chaetiger 2. Posterior part of body and pygidium unknown. Tube unknown. Specimen in alcohol uniformly pale.

Remarks

In general, this species is similar to C. fauchaldi Light, 1991, described from 2070 m depth in the East Pacific, off Panama, but differs in the development of the cephalic rim.

Records

2 specimens. Suppl. material

Lumbriclymene

Diagnosis