| Taxon names | Citations | Turn highlighting On/Off |

Citation: Jordal BH, Smith SM, Cognato AI (2014) Classification of weevils as a data-driven science: leaving opinion behind. ZooKeys 439: 1–18. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.439.8391

Data and explicit taxonomic ranking criteria, which minimize taxonomic change, provide a scientific approach to modern taxonomy and classification. However, traditional practices of opinion-based taxonomy (i.e., mid-20th century evolutionary systematics), which lack explicit ranking and naming criteria, are still in practice despite phylogenetic evidence. This paper discusses a recent proposed reclassification of weevils that elevates bark and ambrosia beetles (Scolytinae and Platypodinae) to the ranks of Family. We demonstrate that the proposed reclassification 1) is not supported by an evolutionary systematic justification because the apparently unique morphology of bark and ambrosia beetles is shared with other unrelated wood-boring weevil taxa; 2) introduces obvious paraphyly in weevil classification and hence violates good practices on maintaining an economy of taxonomic change; 3) is not supported by other taxonomic naming criteria, such as time banding. We recommend the abandonment of traditional practices of an opinion-based taxonomy, especially in light of available data and resulting phylogenies.

Curculionoidea, Scolytinae, Platypodinae, weevil phylogeny, taxonomic naming criteria, Evolutionary systematics, Scolytidae, Platypodidae

Catalogues of plant and animal species are for many scientists essential tools in biodiversity related research, ecology and wildlife management. Publications of this nature include the compilation of large amounts of data from thousands of different literature sources. Without the time and effort devoted to such research activity, most evolutionary and ecological studies are undoubtedly more difficult given the fragmented distribution of literature relevant to any projects on a particular group of organisms. Major taxonomic reviews and taxonomic catalogues organize their contents according to a classification scheme chosen by the author, which may not follow the best evidence for higher level relationships. This creates an unfortunate situation as comprehensive catalogues are frequently cited sources for taxon relationships and as such, may misrepresent the evolution of a group of organisms.

In a recent supplement to the catalogue on the worldwide fauna and taxonomy of Scolytinae and Platypodinae (bark and ambrosia beetles),

Our philosophical debate began over 50 years ago with the growing use of phylogenies to infer classifications. The greatest arguments occurred between the evolutionary systematists who recognized taxa and their rank based on evolutionary uniqueness, including paraphyletic groups, and the cladists (phylogeneticists) who recognized monophyletic (i.e., holophyletic) taxa and their rank based on group hierarchy (

We argue that the application of family category on these two weevil groups is unjustified because: i) evolutionary systematic justification for family rank is unsupported, i.e., the apparently unique morphology of bark and ambrosia beetles is in part shared with other unrelated wood-boring weevil taxa, ii) the suggested classification does not promote an economy of nomenclatural change, i.e., it creates massive paraphyly of the remaining Curculionidae; and, iii) the suggested classification is not supported by other taxonomic naming criteria, i.e., it elevates two relatively young lineages of weevils to the same rank as much older groups.

List of taxa mentioned in the text, with author and year of publication.

| Name | Author & date |

|---|---|

| Anthonomini | |

| Araucariini, Araucarius | |

| Attelabidae | |

| Bagoinae | |

| Baridinae | |

| Bostrichidae | |

| Brachyceridae, -inae | |

| Brentidae | |

| Conoderinae | |

| Cossoninae | |

| Cryphalinae | |

| Cryphalus | |

| Curculionoidea, -idea, -inae | |

| Cyclominae | |

| Dactylipalpus | |

| Dryocoetini | |

| Dryophthoridae, -inae | |

| Entiminae | |

| Hexacolidae, -inae, ini | |

| Homoeometamelus | |

| Hylastes | |

| Hylesininae | |

| Hylurgops | |

| Hyorrhynchini | |

| Hyperinae | |

| Hypocryphalus | |

| Ipinae, -ini | |

| Mesoptiliinae | |

| Molytinae | |

| Phrixosoma | |

| Platypodidae, -inae | |

| Premnobiini, -ina | |

| Scolitarii, Scolytoidea, -idae, -inae, ini, | |

| Scolytoplatypodini | |

| Scolytus | |

| Xyleborini | |

| Xyloctonini | |

| Xyloterini |

Bark and ambrosia beetles were treated separately from other weevils from the beginning of binominal nomenclature (see e.g.

Comparison of weevil classification of extant families as more broadly defined by

| Nemonychidae | Nemonychinae | Nemonychidae | Nemonychinae |

| Cimberidinae | Cimberidinae | ||

| Rhinorhynchinae | Rhinorhynchinae | ||

| Anthribidae | Anthribinae | Anthribidae | Anthribinae |

| Choraginae | Choraginae | ||

| Urodontinae | Urodontinae | ||

| Belidae | Belinae | Belidae | Belinae |

| Oxycoryninae | Oxycoryninae | ||

| Attelabidae | Attelabinae | Attelabidae | Attelabinae |

| Rhynchitinae | Rhynchitinae | ||

| Archolabinae | |||

| Isotheinae | |||

| Pterocolinae | |||

| Eurhynchidae | Eurhynchinae | ||

| Caridae | Carinae | Caridae | Carinae |

| Brentidae | Brentinae | Brentidae | Brentinae |

| Apioninae | Antliarhininae | ||

| Eurhynchinae | Cyladinae | ||

| Ithycerinae | Cyphagoginae | ||

| Microcerinae | Pholidochlamydinae | ||

| Nanophyinae | Taphroderinae | ||

| Trachelizinae | |||

| Ulocerinae | |||

| Nanophyidae | Nanophyinae | ||

| Ithyceridae | Ithycerinae | ||

| Apionidae | Apioninae | ||

| Myrmacicelinae | |||

| Rhinorhynchidiinae | |||

| Curculionidae | Brachycerinae | Brachyceridae | Brachycerinae |

| Microcerinae | |||

| Ocladiinae | |||

| Erirhinidae | Erirhininae | ||

| Tadiinae | |||

| Raymondionymidae | Raymondionymidae | ||

| Myrtonyminae | |||

| Cryptolaryngidae | Cryptolarynginae | ||

| Dryophthorinae | Dryophthoridae | Dryophthorinae | |

| Cryptodermatinae | |||

| Orthognathinae | |||

| Stromboscerinae | |||

| Rhynchophorinae | |||

| Entiminae | Curculionidae | Entiminae | |

| Curculioninae | Curculioninae | ||

| Baridinae | Baridinae | ||

| Conoderinae | |||

| Ceutorhynchinae | |||

| Molytinae | Molytinae | ||

| Cryptorhynchinae | |||

| Magdalinae | |||

| Mesoptiliinae | |||

| Lixinae | |||

| Cyclominae | Cyclominae | ||

| Hyperinae | |||

| Bagoinae | |||

| Cossoninae | Cossoninae | ||

| Scolytinae | Scolytinae | ||

| (2009: Platypodinae) | |||

| Platypodinae | Platypodidae | ||

While entomologists in general have accepted the modern definition of Curculionidae, many forest entomologists that actively work on bark and ambrosia beetle ecology and forest health tend to oppose Crowson’s system. The most prominent opponent was Stephen L. Wood who published a series of influential monographs and reviews (

This brings us to the crux of the matter, namely that weevil relationships and rank can only be objectively assessed through the inclusion of the broadest possible range of characters in a phylogenetic analysis. Bright’s change in rank for bark and ambrosia beetles is not based on carefully designed hypothesis testing of monophyly, but through the use of arguments, similar to

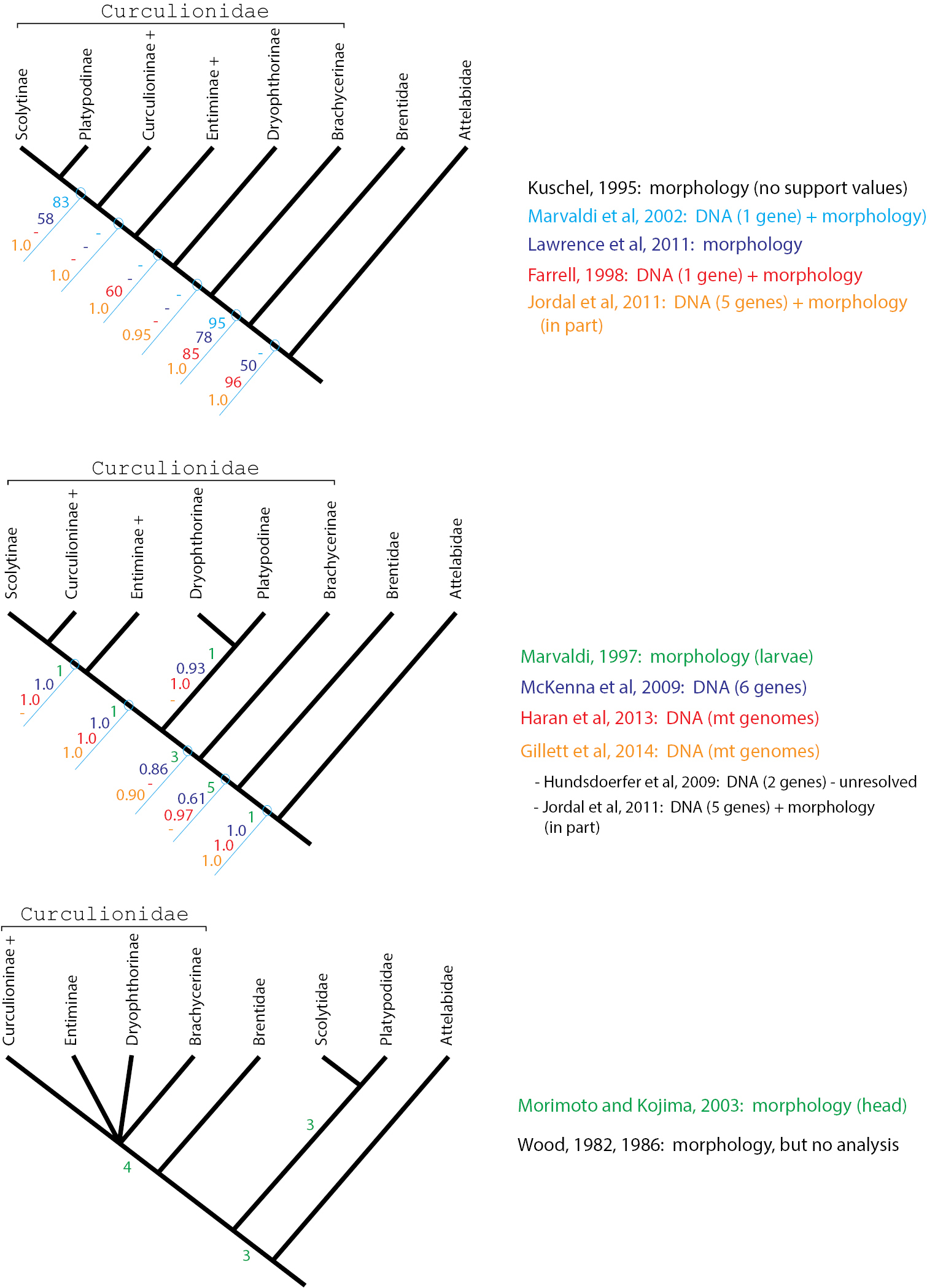

Three alternative phylogeny-based classifications. Numbers on nodes indicate support values according to the method reported in the publication listed in the same colour to the right. Low integers (1-9) indicate Bremer support or number of apomorphic characters, higher integers (>50) indicate parsimony bootstrap support, and proportions (>0.50) indicate posterior probabilities from Bayesian analyses.

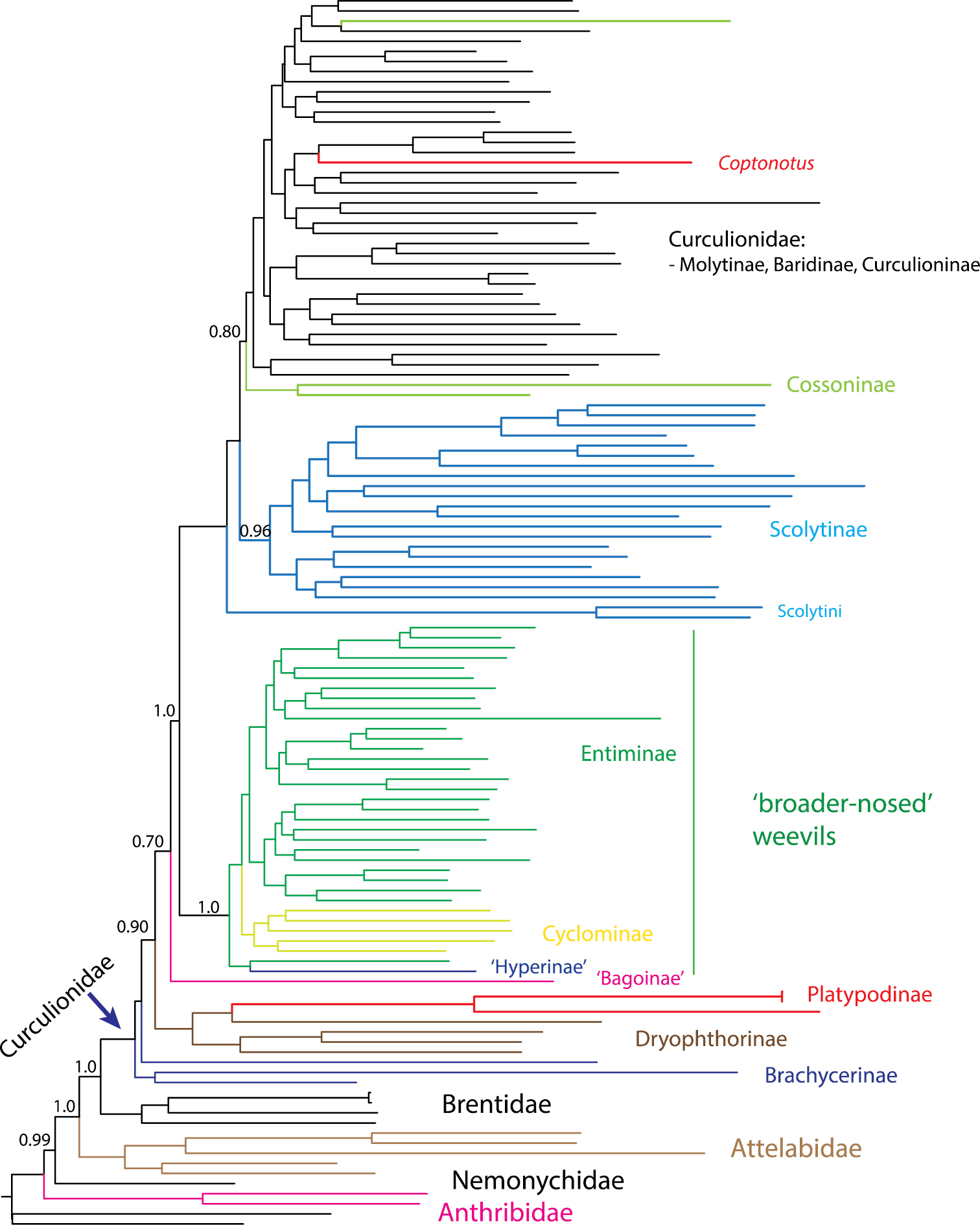

Platypodinae may also belong to a similarly defined Curculionidae, but the long phylogenetic branches that characterise Platypodinae make placement of this subfamily less certain. In several purely molecular phylogenetic studies, they tend to group with Dryophthorinae, but still well inside a more broadly defined Curculionidae (sensu

Mitochondrial genome phylogeny redrawn from

Bright rejects the current classification scheme for weevils mainly based on what he describes as overwhelming morphological differences between Scolytinae and Platypodinae and the remaining Curculionidae. However, phylogenetic analyses of morphological data do not support his view, and both larval (

Moreover, Bright argues that socketed denticles on the tibiae are synapomorphic for Scolytinae, which in fact they are not. Socketed denticles are found throughout the insect world in burrowing species, particularly so in wood-boring beetles. Strong socketed denticles along the lateral margins of all tibiae are found in unrelated wood-boring groups such as the conoderine genus Homoeometamelus (see

Bright also referred to differences in larval head features between Scolytinae and other Curculionidae. This is entirely at odds with published sources showing that Scolytinae is indistinguishable from many other Curculionidae based on larval characters (

Overall, the morphological uniqueness in Scolytinae and Platypodinae fades rapidly when all body parts and all life stages are studied simultaneously in a phylogenetic analysis. The strong arguments for a separate position of Scolytinae and Platypodinae hinges upon the study of few characters which are apparently under strong adaptive selection for optimizing tunnelling behaviour in dead wood. The characters most frequently used to argue for an early separate standing of these groups all appear to be losses or modifications of plesiomorphic features. Optimisation of these features on the best supported phylogenetic topologies (e.g. Fig. 2), demonstrates that the hypostomal teeth are lost multiple times, including certain Cossoninae and Entiminae (

The recognition of Scolytidae, and in most classification schemes also Platypodidae, would render Curculionidae paraphyletic and as a result create more nomenclatural issues and work for current and subsequent weevil taxonomists. In order to maintain monophyly of Curculionidae, many if not most current weevil subfamilies would need to change rank to family given the phylogenetic position of scolytines and platypodines (Fig. 2). Some of these subfamilies are paraphyletic; thus, their change in rank would require the recognition of additional currently unnamed clades as families. As illustrated by the most recent and well sampled study to date (Fig. 2), the mitochondrial genome phylogeny indicates a separate clade of the ‘broader-nosed’ weevils (Entiminae, Cyclominae, Hyperinae) as sister to Scolytus (Scolytini), the remaining Scolytinae, and most other Curculionidae except Brachycerinae, Dryophthorinae and Platypodinae. This means that the erection of Scolytinae to a family would require a similar elevation in status for several Curculionidae subfamilies as families (e.g. Entiminae, Cyclominae and Hyperinae) to restore the monophyletic status of Curculionidae. Without a coordinated change in ranks of equivalent weevil groups, the isolated act on Scolytinae and Platypodinae will cause instability in weevil classification.

There is still much phylogenetic ambiguity in even the most well-sampled weevil phylogenies, thus with greater phylogenetic resolution in future analyses, many of these new recognized families would likely be demoted in rank or synonymized and forgotten. The recognition of Scolytidae and Platypodidae also results in the loss of taxonomic information. As families these groups can only be inferred as beetles with some distinguishing characters. But as weevil subfamilies, these groups are recognised as distinguished weevils, namely as snout-less.

In addition, with the elevation of Scolytinae to full family status, Bright promotes 13 new subfamilies, 10 containing a single tribe, and 3 with a collection of 2, 6 or 12 tribes. Even if everyone accepted ‘Scolytidae’, the change in categories is premature. Bright states that “the ultimate goal of phylogenetic systematics is the development and recognition of monophyletic lineages. As stated above, I herein recognize 13, supposedly monophyletic, subfamilies.” However, he does not cite a phylogeny or discuss synapomorphic characters that would support his supposition of monophyletic subfamilies. Although we share Bright’s view that

There are also issues concerning monophyly and their corresponding category. Bright does not include criteria for deciding which monophyletic groups should be considered subfamilies. We assume his decision is based on large differences among morphological features (a main tenant in evolutionary systematic philosophy) but the classification is subjective without quantifying these differences. For example, Cactopinini and Micracidini are sister (or nested) clades (

Of the other proposed taxonomic naming criteria, time banding (the use of evolutionary age to determine rank) is most applicable to this issue (

The oldest scolytine and platypodine fossils are both of mid-Cretaceous age around 100 (Burmese amber) and 116 Ma (Lebanese amber), and fit nicely with these time estimates (

For the 21st century, taxonomic classification should be based on well-supported, character-rich phylogenies and clear taxonomic ranking (naming) criteria. Instead, the newly proposed classification scheme is derived from an evolutionary systematic perspective, which, despite the phylogenetic evidence to the contrary, is biased by a selection of apparently unique characters. The resulting high cost of change to Curculionidae taxonomy further undermines the proposed classification. We strongly recommend current and subsequent researchers to evaluate classifications conservatively to maintain stability and encourage an economy of taxonomic change that is based on well-supported phylogenies reconstructed with various sources of data. Awaiting the great overhaul of curculionid classifications, the catalogue published by