| Taxon treatments | Taxon names |

|

Turn highlighting On/Off |

(C) 2012 Yves Bousquet. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

All scientific names of Trachypachidae, Rhysodidae, and Carabidae (including cicindelines) recorded from America north of Mexico are catalogued. Available species-group names are listed in their original combinations with the author(s), year of publication, page citation, type locality, location of the name-bearing type, and etymology for many patronymic names. In addition, the reference in which a given species-group name is first synonymized is recorded for invalid taxa. Genus-group names are listed with the author(s), year of publication, page citation, type species with way of fixation, and etymology for most. The reference in which a given genus-group name is first synonymized is recorded for many invalid taxa. Family-group names are listed with the author(s), year of publication, page citation, and type genus. The geographical distribution of all species-group taxa is briefly summarized and their state and province records are indicated.

One new genus-group taxon, Randallius new subgenus (type species: Chlaenius purpuricollis Randall, 1838), one new replacement name, Pterostichus amadeus new name for Pterostichus vexatus Bousquet, 1985, and three changes in precedence, Ellipsoptera rubicunda (Harris, 1911) for Ellipsoptera marutha (Dow, 1911), Badister micans LeConte, 1844 for Badister ocularis Casey, 1920, and Agonum deplanatum Ménétriés, 1843 for Agonum fallianum (Leng, 1919), are proposed. Five new genus-group synonymies and 65 new species-group synonymies, one new species-group status, and 12 new combinations (see Appendix 5) are established.

The work also includes a discussion of the notable private North American carabid collections, a synopsis of all extant world geadephagan tribes and subfamilies, a brief faunistic assessment of the fauna, a list of valid species-group taxa, a list of North American fossil Geadephaga (Appendix 1), a list of North American Geadephaga larvae described or illustrated (Appendix 2), a list of Geadephaga species described from specimens mislabeled as from North America (Appendix 3), a list of unavailable Geadephaga names listed from North America (Appendix 4), a list of nomenclatural acts included in this catalogue (Appendix 5), a complete bibliography with indication of the dates of publication in addition to the year, and indices of personal names, supraspecific names, and species-group names.

Ground beetles, Trachypachidae, Rhysodidae, Carabidae, North America

The Adephaga, a name coined by the Swiss entomologist and botanist Joseph Philippe de Clairville [1742-1830] in 1806, represents the second largest suborder of Coleoptera with an estimated 39, 300 species described to 2005. The group is undisputedly natural, based on the presence of several synapomorphies in the adult and immature stages (Beutel and Ribera 2005: 53; Beutel et al. 2008; Lawrence et al. 2011). The term Adephaga comes from the Greek word adephagos meaning gluttonous, greedy, in reference to the predaceous habits of adults and larvae of the vast majority of the species. Conventionally the Adephaga are divided into two groups, the Geadephaga for the terrestrial families and the Hydradephaga for the aquatic families.

The extant hydradephagan families include the Gyrinidae (about 875 species), Haliplidae (about 220 species), Noteridae (about 250 species), Amphizoidae (five species), Hygrobiidae (six species), Dytiscidae (about 3, 700 species), Aspidytidae (two species), and Meruidae (one species). Some studies, based on structural features of the adult (Burmeister 1976; Baehr 1979) and larva (Ruhnau 1986) as well as molecular data (Shull et al. 2001; Ribera et al. 2002; Hunt et al. 2007), suggest that the Hydradephaga is monophyletic. Other studies, including recent DNA sequence analyses (Maddison et al. 2009), indicate a polyphyletic origin for the complex.

The extant geadephagan groups include the trachypachids (six species), rhysodids (about 355 species), cicindelids (about 2, 415 species), and carabids (about 31, 490 species). The monophyletic origin of the Geadephaga was supported in some structural and molecular studies but rejected in others (see Maddison et al. 2009 for an overview). While the taxonomic concept of the hydradephagan families is stable, that of the geadephagan families is not. Several authors consider either the trachypachids, rhysodids, or cicindelids as Carabidae.

This work catalogues all geadephagan taxa of America, north of Mexico. The last catalogue covering the Geadephaga of the region is that of Bousquet and Larochelle in 1993. Since then relatively few taxonomic studies have been published on the North American fauna. The increased interest toward the inadequately known but amazingly rich Neotropical Region is probably one of the reasons behind the situation. So, is there a need for this catalogue? For one, it is more informative than the previous one. It includes, besides the usual information on nomenclature, the type locality of each available species, locations of the primary type specimens, references to the original synonymies of invalid names, and a short description of the geographical distribution of each species. Furthermore, a number of errors were discovered in the previous catalogue and needed to be corrected.

Brief historyThe first checklist / catalogue covering the North American Geadephaga was the checklist of beetles of the United States by Friedrich Ernst Melsheimer [1784-1873] published in July 1853. The interest for this work originated with the establishment in 1842 of the first entomological society in America, The Entomological Society of Pennsylvania. The compilation of this list was one of the main objects of the Society (Sorensen 1995: 17) and it prevailed upon Melsheimer, the first and only President of the Society, to complete the task. The manuscript was delivered in 1848 to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Its secretary, Joseph Henry, asked Samuel S. Haldeman and John L. LeConte to advise on its publication. The two gentlemen volunteered to update the manuscript, which delayed its release considerably. The work was a straightforward list of valid species, with abridged references and synonyms but without distributional data, arranged under the valid generic names. Although limited to the United States, it included more than 90% of the species known from North America at the time. Melsheimer, a physician by profession, was the son of Frederick Valentine Melsheimer [1749-1814] who in 1806 published the first book on American entomology, a 60-page booklet entitled “Catalogue of insects of Pennsylvania. Part first.” It enumerates 111 genera and 1, 363 species of Coleoptera (Meisel 1929: 367), though almost all of them are nomina nuda.

In April 1866, John Lawrence LeConte [1825-1883] published the first part of a checklist of the Coleoptera of North America (north of Mexico) for the Smithsonian Institution. It covered the Adephaga and a large section of the Polyphaga. The first 49 pages, which included the Adephaga, were reprinted with minor modifications from a list already issued in March 1863. The list included synonyms but no geographical information. The second part of the checklist, covering the Chrysomeloidea and Curculionoidea, was never published. Two additional checklists of North American beetles would be published in the United States during the xix Century, both straightforward lists without geographical data. The first one, issued in 1874, was authored by George Robert Crotch [1842-1874], a British coleopterist who at the time was assistant to Hermann Hagen at the Museum of Comparative Zoology. A supplement to Crotch’s checklist was authored in 1880 by Edward Payson Austin, an amateur coleopterist and member of the Cambridge Entomological Club in its early years. The second checklist was published in 1885 by Samuel Henshaw [1852-1941], then assistant to Professor Hyatt at Lowell Technological Institute. Three supplements, in 1887, 1889, and 1895, were later issued by Henshaw.

In Europe, the German Max Gemminger [1820-1887] and Freiherr Edgar von Harold [1830-1886] published, between 1868 and 1876, a checklist of beetles of the world in 12 volumes, compiling 77, 008 species over 3, 800 pages. The Geadephaga were included in the first (Carabidae including cicindelids and trachypachids), second (paussids on pages 700-706), and third volumes (rhysodids on pages 867-868), all issued in 1868. Along with each specific name the authors listed the publication year as well as the original reference and region(s) of capture. This work spurred a large number of additions and corrections by many coleopterists. It stood alone in its class until the publication of the Coleopterorum Catalogus under the editorship of Walther Junk and Sigmund Schenkling. Published between 1909 and 1940, this catalogue was issued in 170 parts forming 30 volumes and involved the participation of more than 60 entomologists. A list by parts and another by families can be found in Blackwelder (1957: 1022-1034). The Geadephaga were covered in parts 1 (Rhysodidae by Raffaello Gestro in 1910), 5 (Paussinae by R. Gestro in 1910), 86 (Cicindelinae by Walther Horn in 1926), 91, 92, 97, 98, 104, 112, 115, 121, 124, 126, and 127 (Carabidae, including trachypachids, by Ernst Csiki between 1927 and 1933). Second editions of the Rhysodidae, by Walter D. Hincks in 1950, and Paussinae, by Emile Janssens in 1953, were issued much later.

While the Coleopterorum Catalogus was being published in Berlin, Charles William Leng [1859-1941], then director of the museum at the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences, released in 1920 his catalogue of the Coleoptera of America, north of Mexico, still known as the “Leng catalogue.” His goal was “to enumerate systematically all the species of Coleoptera described prior to January 1, 1919 ... with consecutive numbers, synonyms, citation of original description, and an indication of distribution.” Leng and Andrew J. Mutchler in 1927 (covering the years 1919-1924) and 1933 (for 1925-1932), Richard E. Blackwelder in 1939 (for 1933-1938), and Blackwelder and his wife, Ruth M. Blackwelder, in 1948 (for 1939-1947) published supplements to Leng’s catalogue.

In 1972, Ross H. Arnett, Jr. [1919-1999], the catalyst behind the birth of the Coleopterist’s Society and its journal The Coleopterists Bulletin, initiated the “North American beetle fauna project” (NABF) with the help of a small group of coleopterists. The main goal of this cooperative adventure was to “produce a series of manuals for the identification of the species of beetles of the United States and adjacent Canada, and adjacent Mexico.” Although no such book was ever published, a preliminary checklist of North American beetles, known as the “Red Version, ” was compiled by 1976 by Richard E. Blackwelder and Arnett. This version was used as a “working copy” for the next one, the “Yellow Version” defined as the “definitive checklist and the one which will be kept up-to-date.” Of this version, only two families would be compiled and published (July 1977), the Cupedidae by Arnett and the Carabidae (including trachypachids but excluding cicindelids) by Terry L. Erwin, Donald R. Whitehead, and George E. Ball. The “Red Version” was reissued with modifications in 1983 under the editorship of Arnett.

In November 1978, the Science and Educational Administration, USDA, released its first fascicle, covering the family Heteroceridae, of “A catalogue of the Coleoptera of America north of Mexico.” The goal was to “supplant the Leng catalogue and supply additional essential information.” A total of 34 fascicles, treating various family-group taxa, would be published up to February 1997. Among the fascicles, one only, the Rhysodidae by Ross T. Bell in 1985, deals with Geadephaga.

In 1993, Bousquet and Larochelle published the first catalogue specifically devoted to the geadephagan beetles of North America. They listed, for the first time, the original combination of every available species-group taxon and provided a general idea of the distribution of each species by listing state and province records. One of the goals behind their work was to stimulate interest toward publication of distributional records as done regularly in Europe.

In 1998, Wolfgang Lorenz issued the first edition of his “Systematic list of extant ground beetles of the world” compiling 32, 567 species (in 1861 genera) of Geadephaga. Despite being limited to scientific names with their authors and publication years, the list soon became a useful tool to those interested in carabids. A second edition was released in 2005, compiling the same information for 34, 281 extant species, placed in 1929 genera.

The first catalogue of the world Coleoptera published is that of Schönherr issued in four parts, 1806, 1808, 1817 and 1826. The Carabidae were grouped in the following genera: Scarites (23 species), Cychrus (seven species), Manticora (two species), Carabus (340 species), Calosoma (12 species), Galerita (nine species), Brachinus (16 species), Anthia (27 species), Agra (three species), Collyris (four species), Odocantha [sic!] (seven species), Drypta (four species), Cicindela (67 species), Elaphrus (11 species), Scolytes [sic!] (three species), all included in the first volume (1806), and Paussus (ten species) and Cerapterus (two species) included in the third volume (1817). Overall 547 species of Geadephaga were listed along with references and synonyms. By comparison, the number of Carabidae (including Cicindelinae) listed in the four catalogue editions of the Dejean collection amounted to 104 (first edition, 1802), 908 (second edition, 1821), 2494 (third edition, 1833), and 2791 (fourth edition, 1836).

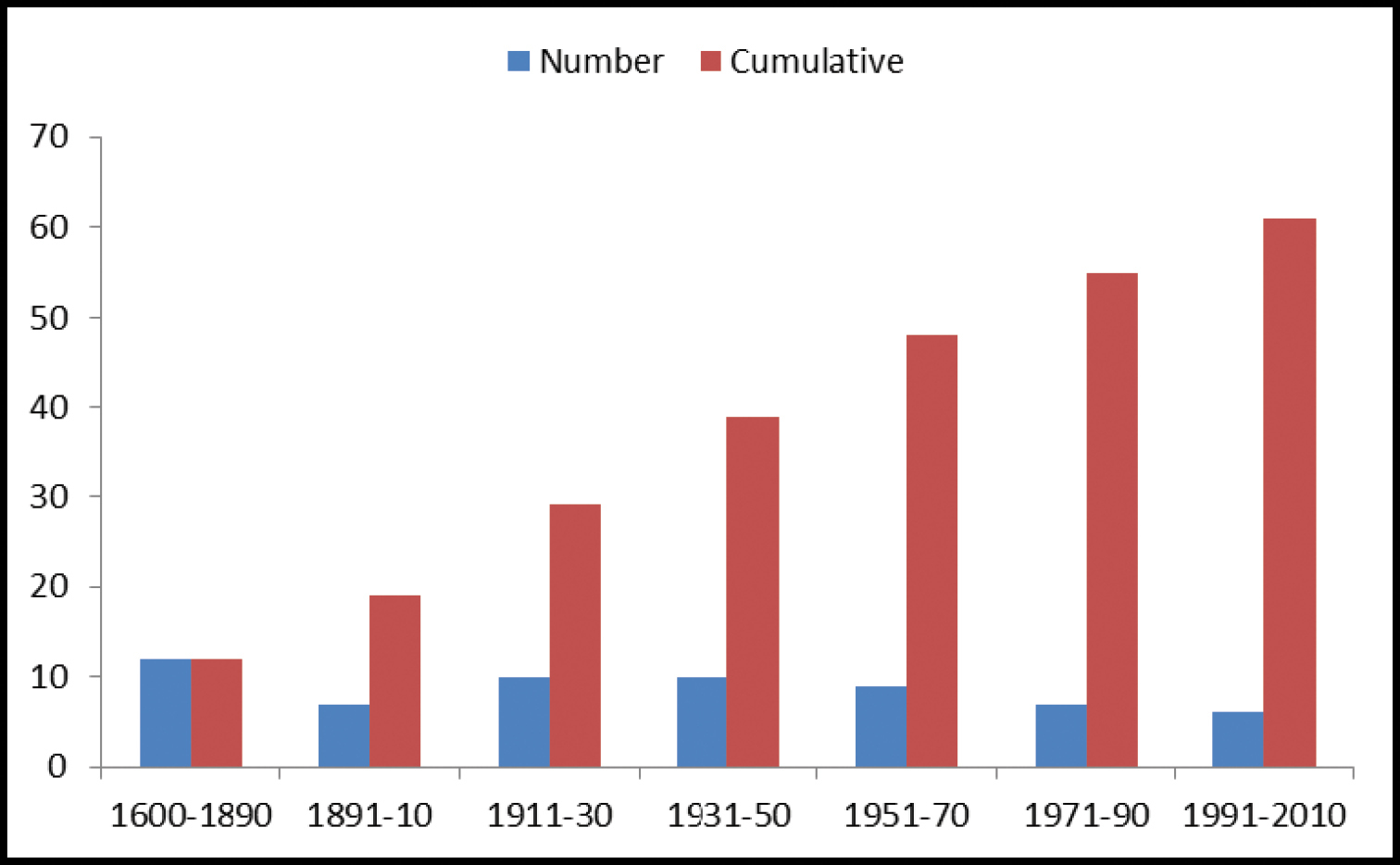

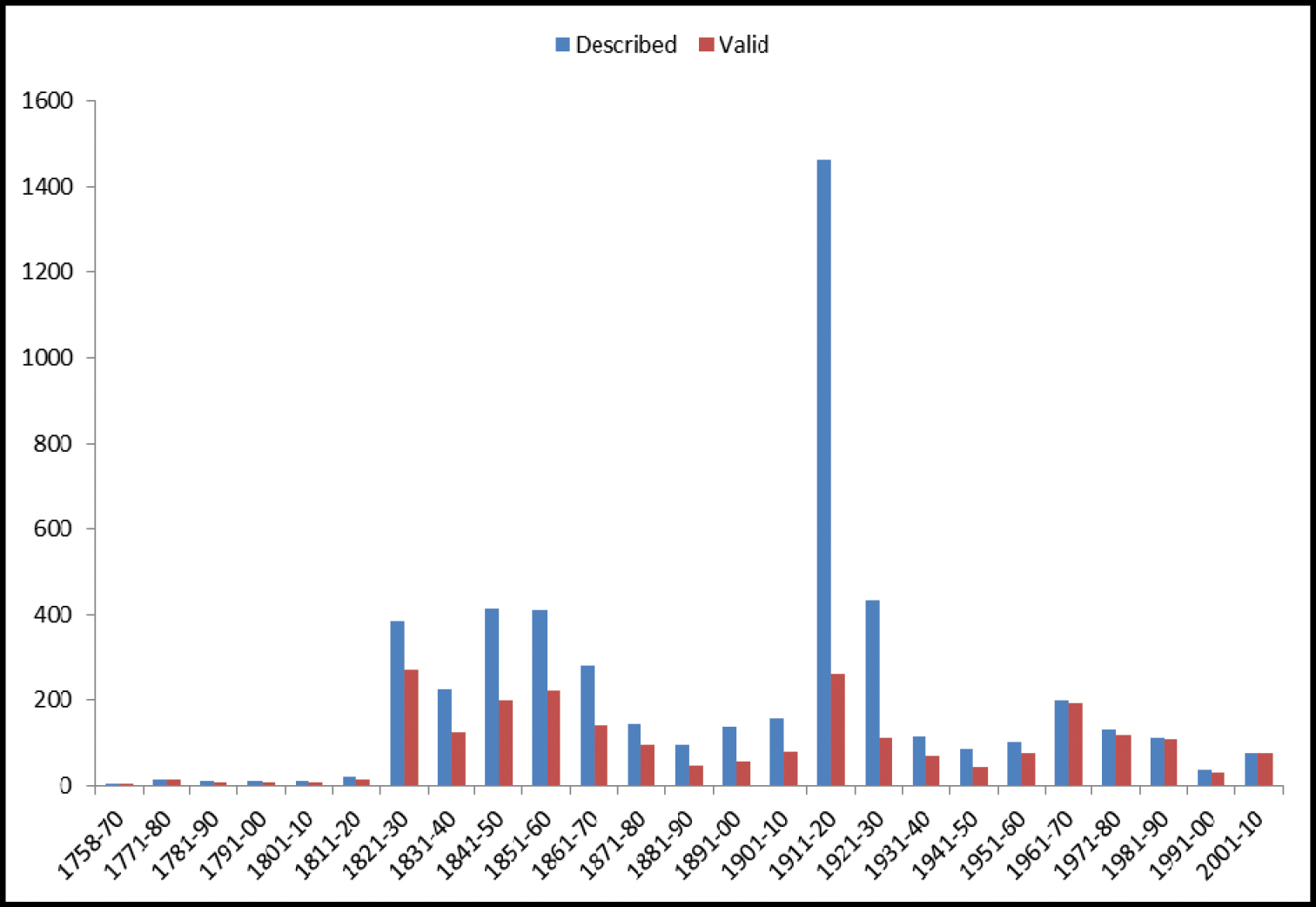

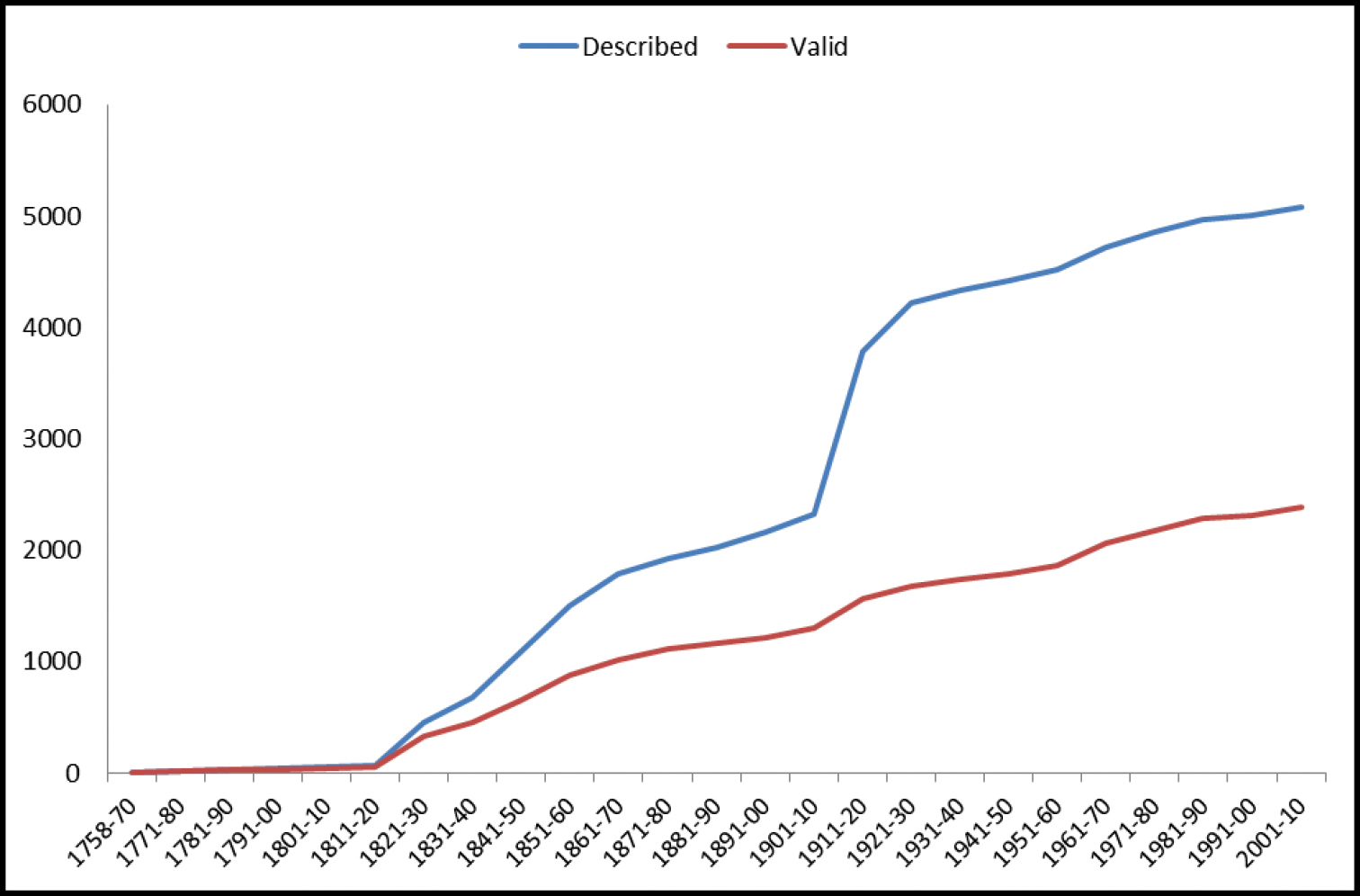

A comparison of the number of valid species and genera between this and previous checklists / catalogues is presented in Table 1.

North American Geadephaga species/genera counts in checklists.

| Publications | Trachyp | Rhysod | Cicindel | Carabid | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melsheimer 1853 | 0 | 3/1 | 64/4 | 935/112 | 1002/117 |

| LeConte 1866 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 65/4 | 1090/107 | 1159/117 |

| Gemminger & Harold 1868 | 2/1 | 2/1 | 61/5 | 1167/124 | 1232/131 |

| Crotch 1874a | 2/1 | 2/2 | 67/4 | 1097/118 | 1168/125 |

| Henshaw 1885 | 2/1 | 4/2 | 70/4 | 1179/114 | 1255/121 |

| Leng 1920 | 2/1 | 4/2 | 114/4 | 2207/207 | 2327/214 |

| Coleopterorum Catalogus 1926-33 | 6/1 | 4/2 | 70/4 | 2916/144 | 2996/151 |

| Erwin et al. 1977 | 3/1 | 9/21 | 109/42 | 2308/169 | 2429/176 |

| Bousquet & Larochelle 1993 | 3/1 | 8/2 | 107/4 | 2230/183 | 2348/190 |

| Present catalogue | 3/1 | 8/2 | 112/12 | 2316/193 | 2439/208 |

1 Species count from Bell (1985b)

2 Species count from Boyd (1982)

The information on species-group taxa comprises a nomenclatural and a distributional component. The nomenclatural component consists of the scientific name with its author, date and page of publication, the type locality (see section Type locality under “Nomenclature” below), and the repository of the name-bearing type of each valid and invalid taxon. In addition, the reference in which a given scientific name is first synonymized is listed. Such references were difficult to find for several names, simply because they were never compiled before. Taxa listed as varieties subsequently to their original descriptions were not considered as listed in synonymy but those listed as aberrations or as “simple varieties” were. Codens used for collection repositories are given in the next section. When available, the accession numbers of name-bearing types for each institution are recorded.

This catalogue deals with extant available taxa. Fossil taxa are listed in Appendix 1. Unavailable names found in the literature are listed in Appendix 4 without comment. Listings of valid species-group names are alphabetic but listings of invalid names are chronologic. Synonyms of adventive and Holarctic species found in North America are selective. Misidentifications by subsequent authors are not listed. All species-group names are given in their original combinations.

The distributional component consists of a list of state and province records, using the same two-letter postal service style abbreviations used in the 1993 catalogue (Table 2), and a short description of the distribution, usually referring to the northeasternmost, northwesternmost, southwesternmost, and southeasternmost states or provinces. In addition, records for Cape Breton Island, the Queen Charlotte Islands, Vancouver Island, and the Channel Islands are indicated in parentheses after their respective provinces or states. Western Hemisphere countries are listed for species found south of the area covered. States and provinces placed in quotation marks in the descriptive section indicate that only the state or province was given without further precision in the reference cited. The starting point for the distributional records used in this work is Bousquet and Larochelle’s (1993) catalogue. However, many of their records were undocumented or came from old lists and were not always reliable. State and province records undocumented or considered doubtful are shown in square brackets following the accepted records. Except for the Amara records which come from identifications generally made by Fritz Hieke, almost all records from CMNH specimens are based on identifications made by Robert L. Davidson, those from LSAM specimens on identifications made by Igor Sokolov, and those from CNC, MCZ, and USNM specimens from identifications or confirmations made by myself. The records provided by Ken Karns and Brian Raber are based on identifications made by Robert L. Davidson.

Two-letter abbreviations for political regions covered by this catalogue.

| AB | Alberta | MA | Massachusetts | OH | Ohio |

| AK | Alaska | MB | Manitoba | OK | Oklahoma |

| AL | Alabama | MD | Maryland | ON | Ontario |

| AR | Arkansas | ME | Maine | OR | Oregon |

| AZ | Arizona | MI | Michigan | PA | Pennsylvania |

| BC | British Columbia | MN | Minnesota | PE | Prince Edward Island |

| CA | California | MO | Missouri | PM | St.Pierre and Miquelon |

| CO | Colorado | MS | Mississippi | QC | Quebec |

| CT | Connecticut | MT | Montana | RI | Rhode Island |

| DC | District of Columbia | NB | New Brunswick | SC | South Carolina |

| DE | Delaware | NC | North Carolina | SD | South Dakota |

| FL | Florida | ND | North Dakota | SK | Saskatchewan |

| GA | Georgia | NE | Nebraska | TN | Tennessee |

| GL | Greenland | NF | Newfoundland | TX | Texas |

| IA | Iowa | NH | New Hampshire | UT | Utah |

| ID | Idaho | NJ | New Jersey | VA | Virginia |

| IL | Illinois | NM | New Mexico | VT | Vermont |

| IN | Indiana | NS | Nova Scotia | WA | Washington |

| KS | Kansas | NT | Northwest Territories | WI | Wisconsin |

| KY | Kentucky | NU | Nunavut | WV | West Virginia |

| LA | Louisiana | NV | Nevada | WY | Wyoming |

| LB | Labrador | NY | New York | YT | Yukon Territory |

The information on supraspecific taxa consists of the scientific name with its author and date and page of publication. Type species of genus-group taxa are also given, in their original combinations, followed by the valid names in parentheses when applicable, and type genera are listed for family-group taxa. Etymology is given for all valid generic names and for some of the invalid names; the works of Brown (1956) and Cailleux and Komorn (1981) have been particularly useful.

The listing of valid supraspecific taxa is “phylogenetic, ” starting with taxa putatively branching off early along the evolutionary path of the group. Synonyms of supraspecific taxa are listed chronologically. If readily available, the first reference in which a given genus-group name is synonymized is included.

In the references section, titles of journals are cited in full. Titles of papers and books using alphabets other than Latin have been translated into English and the original language listed in square brackets after the title. An improvised title is given in square brackets, in the language used by the author(s), to papers without formal title. Unless otherwise noted, all references listed were seen. Except when only the year was found, the date of publication [DP] is given in square brackets at the end of each citation.

Institution / collection acronyms and abbreviationsCollections cited in the catalogue are referred to by the abbreviations listed below.

ALM Alabama Museum of Natural History, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, USA

AMNH American Museum of Natural History, New York, New York, USA

ANSP Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

BMNH The Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom

BYUC Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA

CAS California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, California, USA

CMC Cincinnati Museum of Natural History, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

CMN Canadian Museum of Nature, Gatineau, Quebec, Canada

CMNH Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

CNC Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

CUIC Cornell University Insect Collection, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA

DAPC Darren A. Pollock collection, Eastern New Mexico University, Portales, New Mexico, USA

DEI Institute für Pfanzenschutzforschung (formerly Deutsches Entomologisches Institut), Kleinmachnow, Eberswalde, Germany

EMEC Essig Museum of Entomology Collection, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA

ETHZ Entomologisches Institut, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, Zürich, Switzerland

FFPC Foster Forbes Purrington collection, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

FMNH Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA

FSCA Florida State Collection of Arthropods, Gainesville, Florida, USA

GNM Göteborgs Naturhistoriska Museum, Göteborg, Sweden

HMUG Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

INHS Illinois Natural History Survey, Champaign (Urbana), Illinois, USA

IRSN Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles, Brussels, Belgium

IZWP Museum and Institute of Zoology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Warszawa, Poland

KSUC Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas, USA

LACM Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, Los Angeles, California, USA

LMMC Lyman Entomological Museum, McGill University, Macdonald Campus, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, Canada

LSAM Louisiana State Arthropod Museum, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA

LSL Linnean Society, London, United Kingdom

MCZ Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

MHNG Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, Geneva, Switzerland

MHNP Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France

MSB Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA

MSNG Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, Genoa, Italy

MSNM Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, Milano, Italy

MSNT Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, Trieste, Italy

MSUE Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, USA

MVM Museum Victoria, Melbourne, Australia

NCSU North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

NHMW Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Wien, Austria

NIAS National Institute for Agro-environmental Sciences, Tsukuba, Japan [formerly National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Tokyo]

NMNS National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo, Japan

NMP National Museum, Prague, Czech Republic

NRSS Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm, Sweden

NSNH Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

ODAC Oregon Department of Agriculture, Plant Division, Salem, Oregon, USA

ORUM Collection Ouellet-Robert, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

OSAC Oregon State Arthropod Collection, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA

OSUO Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

PMNH Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA

PURC Purdue State University, West Lafayette, Indiana, USA

SIM Staten Island Museum, Staten Island, New York, USA

SMEK Snow Museum of Entomology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA

SMTD Staatliches Museum für Tierkunde, Dresden, Germany

TAMU Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA

TMB Magyar Természettudományi Múzeum, Budapest, Hungary

TME Texas Museum of Entomology, Pipe Creek, Texas, USA

UAIC University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas, USA

UASM Strickland Museum, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

UBC Spencer Entomological Museum, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

UCD University of California, Davis, California, USA

UCM University of Colorado Museum, Boulder, Colorado, USA

UICU University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois, USA

UMAA University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

UMM Philipps-Universität Marburg, Zoologische Sammlung, Marburg, Germany

UMO The University Museum, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

UMSP University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA

USMT Ueno Science Museum, Tokyo, Japan

USNM National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, DC, USA

USS University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

UZIU Uppsala Universitet, Zoologiska Museum, Uppsala, Sweden

VMNH Virginia Museum of Natural History, Martinsville, Virginia, USA

WSU Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, USA

ZILR Zoological Institute, Academy of Sciences, Saint Petersburg, Russia

ZMH Zoologiska Museum, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

ZMHB Zoologisches Museum, Humboldt Universität, Berlin, Germany

ZMLS Zoological Museum, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

ZMMU Zoological Museum, Moscow University, Moscow, Russia

ZMUA Zoologisch Museum, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

ZMUC Zoologisk Museum, Universitets Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

ZMUO Zoological Museum, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

ZMUT Zoological Museum, University of Turku, Turku (= Åbo), Finland

Besides those used for provinces and states (see Table 2), the following abbreviations are used in the text:

B.P. Before Present

CAN Canada

CBI Cape Breton Island

CHI Channel Islands (Santa Barbara Islands)

DEN Denmark

DP Date of publication

FRA France

ICZN International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature

QCI Queen Charlotte Islands

USA United States of America

VCI Vancouver Island

In addition, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature is sometimes abridged to “Commission” and United States of America to “United States.”

Geographical termsFor simplicity, North America, north of Mexico, is referred to simply as North America in the text. Middle America refers to Mexico and the republics of Central America taken collectively. The West Indies refers to the Greater and Lesser Antilles and the Bahamas. The North American continent proper is referred to as North and Middle America.

For practical reasons, the zoogeographical regions of the world are defined following national boundaries as much as possible. The Nearctic Region corresponds to Canada, the continental United States, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, and Greenland. Although the region extends into Mexico, its southern limit is difficult to define and often varies depending on the group under study. This concept implies that North America and the Nearctic Region are equivalent in this work. The Neotropical Region comprises Middle America and South America. The Afrotropical Region consists of Africa, including Madagascar and a number of smaller islands of the Indian Ocean, such as the Comoros, the Mascarene Islands, and the Seychelles, and of the Atlantic Ocean, such as Cape Verde Islands and São Tomé, but excludes the northern countries of Morocco (including Western Sahara), Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt west of the Suez Canal, and the Canary and Madeira Islands. The limits of the Palaearctic Region are similar to those used in the Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera (Löbl and Smetana 2003: 8). The region thus comprises Europe, Africa north of the Sahara, and Asia as far south as the Arabian Peninsula, Pakistan, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, Arunachal Pradesh, China, and Taiwan. The Oriental Region is Asia south of the regions used to define the southern limit of the Palaearctic Region. It includes all the Malay Archipelago (except New Guinea). The Australian Region comprises Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea, and some smaller islands of the Pacific, such as Fiji, New Britain, New Caledonia, and Solomon Islands.

The New World consists of the Nearctic, Neotropical, and Australian Regions combined and the Old World of the Oriental, Palaearctic, and Afrotropical Regions grouped. The Northern Hemisphere is the Nearctic and Palaearctic Regions combined and the Southern Hemisphere is the Afrotropical, Oriental, Australian, and Neotropical Regions united. The Western Hemisphere consists of the Nearctic and Neotropical Regions and the Eastern Hemisphere of the Palaearctic, Afrotropical, Oriental, and Australian Regions. Far East used in reference to the Palaearctic Region includes the Russian Far Eastern Region, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, Taiwan, and China excluding the Autonomous Regions of Inner Mongolia, Sinkian Uighur, and Tibet. Middle East is used for the southwestern Asian countries, including Egypt, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

The adjective “Holarctic” is used to denote a taxon that occurs naturally in both the Nearctic and Palaearctic Regions. The adjective “Australian” (as in “Australian species”) refers to the zoogeographical region, not to the country itself. The adjective “worldwide” is used to denote a genus-group or family-group taxon represented by at least one native species in all six zoogeographical regions as defined above including both the European and Asian parts of the Palaearctic Region. The adjective “endemic” indicates that the taxon is found only in the region listed.

Names of geographical places are given in their current English forms based on Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, third edition (1997).

NomenclatureThe rules outlined in the fourth edition of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclatural, published in 1999, have been followed throughout this catalogue. The following are comments about some nomenclatural issues.

Principle of priority. Priority for identical taxa made available the same year, whether under the same name or not, is determined by the date, other than the year, of publication. If not specified in the work itself, the publication date is the earliest day or month on which the work is demonstrated to be in existence (ICZN 1999: Article 21.3). When both works are published or assumed to be published the same day, precedence is determined by the First Reviser (Article 24.2). Unless listed in the work itself, dates of publication besides the year can be demonstrated only for some works. Those without specific dates are listed as published the last day of the year (Article 21.3.2) and priority goes to the work with a “demonstrated” date of publication. However, the situation is subject to change with new bibliographic discoveries, which could challenge the validity of synonyms (as well as relative precedence of homonyms and validity of nomenclatural acts) and bring nomenclatural instability. In this catalogue, priority was given to the publication “in prevailing usage” when the dates of publication were determined from external sources.

New taxa. In the xviii and first half of the xix Century it was common practice for authors not to indicate the attribution of the new species-group taxa. Instead, some authors added the word mihi after the specific name, usually to indicate a taxon that the author, himself, was describing. Several collectors provided names for their specimens, even for undescribed ones, and these specimens often circulated among European coleopterists through exchange, gift, or sale. Many undescribed species were subsequently described or illustrated under the collector’s names by different authors. For these, citations are provided in this catalogue only to the first description or illustration of each species unless the term “new species” or an equivalent expression (such as an asterisk preceding the specific epithet as in Say 1823a

New taxa first published as synonyms. The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature admits the availability of taxa first published in an available work as junior synonyms and adopted before 1961 as valid taxa or treated as senior homonyms (ICZN 1999: Article 11.6.1). In such cases the taxa date from their first publication as synonyms. Even though this ruling has existed since the publication of the ICZN first edition in 1960, it has rarely been enforced in the carabid literature. A few cases were found during the preparation of this catalogue. For example, Notiophilus sylvaticus has been credited in the past to Eschscholtz (1833: 24) but the name was first proposed as a junior synonym of Notiophilus biguttatus Fabricius by Dejean (1831: 589). The name is credited to Dejean (1831) in this catalogue. It is possible that other cases like this one will eventually be found.

Lectotype. Prior to 2000, a lectotype could be selected by using the term “the type” instead of “lectotype” (ICZN 1999: Article 74.5). The words “type” and “holotype” are also acceptable if the author unambiguously selects a particular syntype to act as the unique name-bearing type of the taxon. This is the case for almost all designations using the word “type” or “holotype” relating to North American Carabidae published after 1950, in particular by George E. Ball and his students. In this catalogue the expression “lectotype [as type]” or “lectotype [as holotype]” applies to such cases. Unfortunately the Commission does not mandate the addition of “lectotype” labels to selected specimens, which often creates ambiguity when authors fail to do so.

Type locality. According to the ICZN (1999: Article 76.1), the type locality is the geographical place of capture of the primary type (holotype or lectotype). In the absence of a primary type, the type locality encompasses the localities of all the syntypes (Article 73.2.3). This information can be obtained from labels attached to primary types or to syntypes or from the original publication (referred to as “original citation” in the text) whichever is more inclusive, or inferred from the title of the publication or even from the name of the species. When a neotype is designated, its place of capture becomes the type locality (Article 76.3) even if the specimen was collected outside the original area. In this catalogue, type localities taken from labels or from original publications are listed as indicated although the order of the elements is sometimes changed; any additional information is placed in square brackets. Many species described in the xviii and xix Centuries had but little informative place of origin, such as a country, state, province, or large geographical area (e.g., Rocky Mountains or Lake Superior). Lindroth (1961-1969) restricted the type locality of several of these North American species by selecting a specific locality or a county within the original region specified. This practice is followed in this catalogue and specific type localities are selected for several species-group taxa. Of course, only localities where a given species was actually collected can be selected.

Notable private carabid collectionsMany North American species of carabids described in the xix and beginning of the xx Centuries were from specimens held in private collections. The whereabouts of these collections are important to taxonomists. Some of the more significant ones are discussed.

Pierre François Marie Auguste Dejean (1780-1845) CollectionDejean, a French military officer by profession, certainly held the largest private beetle collection of his time, which he built through exchanges, purchases, gifts, and his own collecting in various parts of Europe. He described a total of 289 new carabid species-group taxa from North America, of which 182 (63%) had not been described earlier according to the present catalogue. At the sale of his collection in 1840, the carabid section (which also included the agyrtid genus Pteroloma) was the most significant, not only because it contained 3, 014 species and 17, 914 specimens, but because it was the only one to include name-bearing types. Dejean did not describe a new species-group taxon during his lifetime that he did not consider a carabid. Dejean’s carabid collection (including tiger beetles) was purchased for 7, 000 francs by Marquis F. Thibault de LaFerté-Sénectère who sold it, along with his own carabids, to Baron Maximilien de Chaudoir [q.v.] in 1859. Dejean’s carabid specimens are at MHNP today. Lindroth (1955b) discussed the name-bearing types and status of almost all North American species described by Dejean.

Thomas Say (1787-1834) CollectionSay was the first naturalist born in North America to describe new species of beetles from this continent. In the course of 17 years (1817-1834), he described 164 carabid species from North American material which he believed were new to science. Based on their current status, 142 (87%) had effectively not been previously described. Say left his collection by verbal bequest through his wife to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia in 1834 (Weiss 1936: 277). After his death, which occurred in October of the same year, the collection was shipped from New Harmony, Indiana, to Philadelphia through New Orleans. In 1836, Charles Pickering sent Say’s insects to Thaddeus W. Harris in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in order to “put them in good order, and return them in a condition to be preserved” (Harris to D.H. Storer, 2 November 1836). In the same letter Harris reported “They [Say’s specimens] arrived about the middle of July; but on examination were found to be in a deplorable condition, most of the pins having become loose, the labels detached, and the insects themselves without heads, antennae and legs, or devoured by destructive larvae, and ground to powder by the perilous shakings which they had received in their transportation from New Harmony.” In a letter to C.J. Ward, dated 8 March 1837, Harris wrote “I assure you that Mr. Say’s cabinet does not contain one half of the species which he has described; of the insects in it, many are without names, and all more or less mutilated, and so badly preserved that most of them are now absolutely worthless.” On July 16, 1838, Harris indicated in a letter to S.G. Morton (see Fox 1902: 11) that he had “been obliged to bake a considerable part of the insects lately belonging to Mr. Say twice, and some of them three times, in order to destroy the vermin with which they are infested.” Say’s collection was returned to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia in March 1842 “in such a state of ruin and dilapidation as to be almost useless” (Ruschenberger 1852: 25).

During his life, Say sent some of his specimens abroad including many to Dejean in Paris (see Dejean 1826: vi). Fortunately Dejean’s carabid collection has remained intact and in good condition to this day. In their attempt to bring taxonomic stability to Say’s names, Lindroth and Freitag (1969) selected lectotypes for eight carabid species described by Say for which Say’s authentic specimens could be located in Dejean’s collection. They also designated neotypes from the MCZ material for 131 of the remaining 156 of Say’s species leaving the tiger beetles (14 species) and a few taxa, all currently considered invalid, without type specimens. Say’s species were interpreted by Lindroth and Freitag from LeConte’s concept according to his collection. LeConte never saw Say’s collection and his interpretation of Say’s species came exclusively from the original descriptions which he considered adequate: “The entire destruction of his [Say’s] original specimens would be the subject of much greater regret, were it not for the fact that his descriptions are so clear as to leave scarcely a doubt regarding the object designated. I am thus enabled to assign to nearly all of his Coleoptera their proper place in the modern system” (LeConte 1859d: vi).

Thaddeus William Harris (1795-1856) CollectionHarris, well known for his work in economic entomology (his profile having appeared on every cover of the Journal of Economic Entomology for more than 35 years), described 28 new carabid species from North America. Ten (36%) are considered valid in this catalogue. To his defence, several of his species were made available by the posthumous publication of some of his letters several decades after they were written. At Say’s suggestion, Harris sent his entire collection to Thomas Say in Philadelphia, in 1825, who labeled the specimens as well as he could. Harris’ collection, which included “4, 838 specimens in 2, 241 species of Coleoptera, ” contained “many typical specimens described by Harris, Say, and others” (Scudder 1860: 72). It was bought by friends in 1858 and presented to the Boston Society of Natural History. Harris’ collection was transferred to the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Cambridge in April 1941 (Darlington 1941b: 273) where it stands separately from the general collection in two standard 25 drawer cabinets.

Gustav Graf von Mannerheim (1797-1854) CollectionMannerheim, a Finnish noble by birth and wealthy by inheritance, described 72 new North American carabid species, all from Alaska and California. Of these, 23 (32%) had not been described previously. Mannerheim never visited the New World and his descriptions were based on specimens brought back chiefly by Russian collectors such as Johann F. Eschscholtz, Eduard L. Blaschke, Egor L. Tschernikh, and Il’ia G. Vosnesensky. His library and personal collection, which consisted, at the end, of 18, 000 species and nearly 100, 000 specimens, were sold for the sum of 8, 000 silver rubles by his widow, Countess Eva Mannerheim, in 1855 to the University of Helsinki. The money used to buy the collection came from a loan made by the Emperor to the University with the understanding that the University will pay back annually the sum of 500 rubles to the Imperial Bank of Finland which will use it for poor- and workhouses in the country (Rein 1857). Mannerheim’s collection is kept separately at the University of Helsinki (Silfverberg 1995: 43).

Jules Antoine Adolphe Henri Putzeys (1809-1882) CollectionPutzeys described 38 new North American species of carabids; 15 (39%) are listed as valid in this catalogue. He worked in close collaboration with Chaudoir, the leading carabidologist of the time, and described several new species from specimens in Chaudoir’s collection. These specimens are now in MHNP. He also gave many of his own types to Chaudoir. His personal collection was bequeathed in 1885 to the Société Royale Belge d’Entomologie under the care of the Musée Royal d’Histoire Naturelle in Brussels. Putzeys’ collection consisted of 26, 429 specimens of carabids (including cicindelids) and 6, 123 species (Preudhomme de Borre 1885: clx) as well as many other beetles and various insects.

Victor de Motschulsky (1810-1871) CollectionMotschulsky, a Russian Imperial Army Colonel, described 121 new geadephagan species from North America; 27 (22%) were undescribed at the time based on current practice. A large part of this material came from a 10-month trip he made in 1853-54 to the United States and Panama. He collected at several locations including New York, Niagara Falls, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Cawington, Lexington, the Mammoth Cave, Nashville, Louisville, New Orleans, Mobile, Montgomery, Atlanta, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia. In the last city, he visited LeConte, Haldeman, Melsheimer, and Zeigler. The first three gentlemen gave Motschulsky several specimens from their collections including “types” (Motschulsky 1856: 16). LeConte also identified part of the beetles Motschulsky collected in Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and Carolina. Motschulsky’s main collection, which included almost 60, 000 specimens and about 4, 000 types of beetles, was bequeathed to the Société Impériale des Naturalistes de Moscou. It was stored in poor condition and suffered considerable damage before it was acquired in 1911 by the Zoological Museum, Moscow Lomonosov State University (Antonova 1991: 72). Keleinikova (1976) catalogued the carabid syntypes of Motschulsky’s collection at ZMMU.

Samuel Stehman Haldeman (1812-1880) CollectionHaldeman described 45 new carabid species from North America; 22 (49%) had not been described previously. In 1869 Haldeman, who had purchased Hentz’s collection, sold his collection of beetles to Simon Snyder Rathvon of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, “for about what the cases cost” (Rathvon in Geist 1881: 125). Rathvon’s collection and library were purchased for $1, 000 by Henry Bobb of East Greenville, Pennsylvania, and presented to the Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, as a memorial of his son (Dubbs 1903: 369). In a letter dated April 1875 and addressed to Alexander Agassiz (see below), John L. LeConte stated that he owned “all the unique types” of Haldeman. This leads one to speculate that Haldeman, a close friend of LeConte, gave his name-bearing specimens to LeConte prior to selling his collection to Rathvon.

Maximilien Stanislavovitch Baron de Chaudoir (1816-1881) CollectionRussian aristocrat of French origin, Chaudoir was not the typical insect collector. He made a single extensive collecting trip in his life, a 40 day-journey to the Caucasus in company of M.H. Hochhuth in 1845. His collection was mostly built through purchases and gifts. The single most significant purchase was LaFerté-Sénectère’s carabid collection in 1859 which included Dejean’s original specimens. In January 1874 Chaudoir gave his tiger beetle specimens, representing 713 species, to MHNP. After his death in May 1881 his collection passed into the hands of René Oberthür in Rennes as agreed upon between Chaudoir and the Oberthür brothers. Over nearly five decades, Chaudoir described 126 new carabid species based on specimens collected in North America; 58 (46%) had not been described earlier based on this catalogue.

René Oberthür died in April 1944 and his collection, certainly one of the two largest private beetle collections ever built, was classified as “monument historique” in January 1948 by the French government. The collection, which included at least five million specimens, was acquired for the sum of 32 million francs by the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris (MHNP) in 1951 (Cambefort 2006: 249).

Henry Ulke (1821-1910) CollectionAlthough Ulke described only two North American carabids in his life, Bembidion nevadense in 1875 and Pterostichus johnsoni in 1889, his collection, which he sold in 1900 to the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, was used extensively by LeConte and Horn and contains numerous syntypes of new species described by the two coleopterists. However, recognition of many of these syntypes can be difficult. Sometimes all syntypes were retained by LeConte and Horn while on other occasions all or some of them were returned to Ulke. Furthermore, syntypes returned to Ulke were often reincorporated in his collection with others of the same species from the same place. Usually these were marked with a number or colored square, but since many syntypes were left unmarked at the time, it is sometimes impossible to recognize them at the Carnegie Museum (Robert L. Davidson pers. comm. 2008).

John Lawrence LeConte (1825-1883) CollectionLeConte is without doubt the most outstanding North American coleopterist of the xix Century, not only because he described 514 new genus-group and about 4, 730 new species-group taxa of beetles (Henshaw 1882: 270), but because he was the first to work seriously on the classification of the North American fauna. During his scientific activity, which lasted almost 40 years, he described 724 new species-group taxa of Geadephaga from North America, 439 (61%) of which were not previously described. LeConte built his collection through his own collecting but also from gifts he received and identifications he provided to many persons from whom he usually retained all or some of the specimens. There is also little doubt that his father, Major John Eatton LeConte

In April 1875, LeConte wrote to his friend Alexander Agassiz, director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology in Cambridge, and expressed the wish that his collection be deposited at the museum after his death

LeConte used small colored paper disks to indicate the provenance of his specimens. The color system used is as follows:

Pale blue Lake Superior, Canada

Pink Middle states, i.e., Maryland, Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and possibly also Connecticut and Rhode Island

Pale pink Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts

White Northern and eastern states, Canada, and possibly also Alaska

Orange (brick red) Southern and Gulf states, i.e., Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and possibly also eastern Tennessee and Arkansas

Dark red Texas

Yellow Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, western Tennessee, Kentucky, and possibly Iowa and the southern edge of the Great Lakes

Pale green Nebraska, Kansas, North Dakota, South Dakota, Oklahoma, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana

Dark green New Mexico

Black Utah

Silver Arizona and Valley of Gila (so including also southwestern New Mexico)

Silver with edge cut Baja California, Mexico

Gold California

Dark blue Oregon, Washington

Brown Russian America, i.e., probably the region around Colony Ross, a farming community about 75 miles north of San Francisco along the coast in California, and Alaska

George Henry Horn (1840-1897) CollectionA physician by profession, Horn authored or coauthored more than 250 papers, in which he described 154 new genera and more than 1, 600 new species of beetles, including 103 North American Geadephaga. Based on the current classification, 75 (73%) of his new geadephagan species had not been described previously. His collection and library were bequeathed to the American Entomological Society, which deposited them at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. In October 1974, the Horn and William G. Dietz collections were delivered to the Museum of Comparative Zoology in return for the Scudder and Morse orthopteroid insects of the MCZ (Philip D. Perkins pers. comm. 2004; see Lawrence 1973: 151). Horn’s collection is preserved along with that of LeConte apart from the general collection.

Thomas Lincoln Casey (1857-1925) CollectionFrom 1884 to the end of his life, Casey described 1, 864 new species-group taxa of North American Geadephaga; only 307 (16%) had not been described previously based on current concepts. Still many of his remaining “valid species” have not been subsequently studied, particularly those belonging to small species of the tribe Harpalini, and a substantial proportion will certainly end up in synonymy. Furthermore, several of Casey’s species are valid simply by chance as he did not recognize or study the proper characters (such as the male genitalia) that distinguished them from their closely related taxa known at the time. His collection, consisting of almost 117, 000 specimens, including name-bearing types for more than 9, 200 species-group taxa (Buchanan 1935: 7; Blackwelder 1950: 65), was built through Casey’s own collecting and by purchases. It was bequeathed to the United States National Museum in Washington, D.C. Casey (1918: 291) stated that “about a dozen” of his types “disappeared from ... [his] collection while temporarily at the Cambridge Museum.” The syntypes of some of these species (e.g., Bembidion militare, Tachys occultator, Amara pallida, Amara ferruginea, and Amara marylandica among Carabidae) are at the MCZ. Casey did not designate holotypes as such and therefore, unless he expressly indicated in the original description that he had but a single specimen or that a lectotype had been designated, all type specimens in his collection are syntypes.

Willis Stanley Blatchley (1859-1940) CollectionBlatchley described 12 new North American carabid species; only two (17%) are considered valid in this work. His library and large insect collection, which included 470 name-bearing specimens, were given to Purdue University. Blatchley did not select type specimens in his publications but subsequently designated lectotypes [as types] for all the new species he had described (Blatchley 1930: 33-50).

Charles Frederic August Schaeffer (1860-1934) CollectionSchaeffer, curator of the insect collection at the Museum of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, described 30 new carabid species; 22 (73%) are still valid today. In 1929, the Brooklyn Museum transferred 37, 100 insect specimens, including many of Schaeffer’s carabid types, to the USNM (Debbie Feher pers. comm. 2008). Currently the type material of 25 (possibly 26) of Schaeffer’s species-group taxa are in the USNM. It is clear in his 1910 paper that Schaeffer was selecting one of the specimens from his series as “the type.” However he may not have labeled them as such because lectotypes have been designated for several of his new species by various authors.

Henry Clinton Fall (1862-1939) CollectionA teacher by profession, Fall owned one of the largest private collections of North American beetles toward the end of his life, with an estimated 250, 000 specimens (including those of Charles Liebeck which came to Fall in the 1930s) representing between 14, 000 and 15, 000 species or about 90% of the fauna of the time (Darlington 1940a: 46) if one excludes the “species” described by Casey. Over a period of about 40 years, Fall described 47 new North American carabid species-group taxa; 31 (66%) are still considered valid today. He left his collection, together with his correspondence, notebooks, and reprints, to the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University where his specimens are kept separately at the end of each genus in the general collection. In one of his 1910 papers, Fall designated holotypes (as “the type”) for the first time. From this publication, “type” specimens labeled as such in his collection are considered holotypes. All original specimens of his new species described prior to 1910 should be considered syntypes. Type labels on some of these specimens were probably added after the publication of the original descriptions.

Roland Hayward (1865-1906) CollectionHayward, a member of the Boston Stock Exchange and of the Boston Society of Natural History, described 42 new species of carabids from North America, all in the tribe Bembidiini and the genus Amara. Currently 32 (76%) are considered valid. His collection, which he built through purchases, gifts, exchanges, and his own collecting in New England as well as in Colorado, Manitoba, and New Brunswick, was bequeathed to the Museum of Comparative Zoology in Cambridge. Hayward did not designate type specimens for his new species.

Edwin Cooper Van Dyke (1869-1952) CollectionProfessor Van Dyke described 73 new carabid and one new trachypachid species from North America; 54 (73%) of which had not been described previously based on their current status. His collection, consisting of about 200, 000 specimens (Essig 1953: 88), was presented to the California Academy of Sciences in 1924 where the holotypes of all but three of his 74 new species of Geadephaga are currently stored.

Howard Notman (1881-1966) CollectionNotman described 38 new carabid species from North America between 1919 and 1929; 21 (55%) had not been described previously based on their current status. In 1948 he donated his entire collection to the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences, where it is still today (Smetana and Herman 2001: 118). Based on Hennessey’s (1990) type catalogue of that institution, type specimens of all new species Notman collected himself, most from the Adirondacks where he owned a summer home, are in his collection in SIM (18 in total). He also described several new species from material owned by institutions, such as the USNM. Notman did not designate type specimens in his papers of 1919 and 1920 but did so after.

Classification of GeadephagaUnfortunately, there is no consensus among coleopterists concerning the classification of Geadephaga even at the family level. Some authors rank the cicindelids, rhysodids, and trachypachids as Carabidae while others consider one, two, or all three groups as distinct families. Even the paussines are sometimes raised to family level by modern authors. At this time, I prefer to classify the Geadephaga into three families, i.e., Trachypachidae, Rhysodidae, and Carabidae.

Following Jeannel’s (1941b-1942) classification of the carabids of France, a number of authors, mostly French and Spanish taxonomists, still recognized several families of “ground beetles.” Such an approach does not add anything to the understanding of carabid evolution. It simply adds another level to the Linnaean classification. If Jeannel’s approach is followed, it could and should have an impact on the classification of the other adephagan groups, particularly the dytiscids. Since I have been under the influence of Lindroth’s work on the carabids of Canada and Alaska, Jeannel’s approach seems to me unjustified.

Following is a discussion of the family-group taxa of Geadephaga.

Family Trachypachidae. Monophyly of this family is well supported by larval and adult apomorphies (Arndt and Beutel 1995; Beutel 1994; Beutel 1998). The systematic position of this group, however, is contentious. Bell (1966b, 1967), Bils (1976), Evans (1977a, 1985), Hammond (1979), Ward (1979), Burmeister (1980), Roughley (1981), Nichols (1985c), Beutel and Belkaceme (1986), Ruhnau (1986), Beutel and Roughley (1988), Acorn and Ball (1991), Arndt (1993), Deuve (1993), Arndt and Beutel (1995), Arndt (1998), and Beutel (1998) provided or discussed elements suggesting that trachypachids are more closely related to hydradephagans or part of Hydradephaga (i.e., Dytiscoidea) than to carabids. While most authors have regarded the Hydradephaga and Carabidae as distinct phyletic lineages, Bils (1976) and Nichols (1985c) argued that the hydradephagan-trachypachid lineage may have arisen within the Carabidae. Kavanaugh (1986) reevaluated the evidence supporting relationships of Trachypachidae with Hydradephaga. He concluded that trachypachids could be the sister-group of carabids and ranked the group as a subfamily within the Carabidae. Ponomarenko (1977) also postulated, from fossil evidence, that trachypachids and carabids are sister-groups that evolved from a common eodromeid ancestor. Beutel and Haas (1996), Kavanaugh (1998: 337), Fedorenko (2009), Dressler and Beutel (2010), and Martínez-Navarro et al. (2011) found support for monophyly of a clade including trachypachids and carabids. Recent molecular studies also suggested that trachypachids are more closely related to Geadephaga than to Hydradephaga (Shull et al. 2001; Maddison et al. 2009). In addition, pygidial gland compounds in trachypachids are more similar to those known from Carabidae than from Hydradephaga (Attygalle et al. 2004: 586). In this catalogue, trachypachids are included in the Geadephaga and given family rank.

The Trachypachidae includes two extant genera: Systolosoma Solier with two species in Chile and Argentina and Trachypachus Motschulsky with four species, one in Eurasia and three in western North America.

Many putative trachypachid fossils were found in Mesozoic deposits of Asia. Ponomarenko (1977), who studied the material, included all seven genera of trachypachid fossils in a distinct subfamily, Eodromeinae. Beutel (1998: 83) pointed out that the affinities between trachypachids and eodromeines are unclear because there are no apparent synapomorphic character states between the two groups.

Family Rhysodidae. Traditionally ranked as a distinct family, rhysodids (also known as wrinkled bark beetles) have been included within the family Carabidae in recent years by several authors following evidence or discussion provided by Bell and Bell (1962), Bell (1970), Forsyth (1972), Reichardt (1977), Baehr (1979), Beutel (1990, 1992c), Yahiro (1996), Bell (1998), Liebherr and Will (1998), and others. Some authors have treated the group as a tribe related to Scaritini or Clivinini. Reichardt (1977: 393) stated that rhysodids were “closest” to salcediines and Bell (1998: 268) even suggested that the genus Solenogenys Westwood, traditionally included within the Salcediini, is the sister-group to rhysodids. Erwin (1991a: 10) on the other hand included rhysodids within his subfamily Psydrinae along with gehringiines, psydrines, moriomorphines, patrobines, trechines, zolines, pogonines, and bembidiines. Molecular data published by Maddison et al. (1999: 125) suggest that rhysodids could be the sister-group to cicindelids and that both could be closely related to the subfamily Harpalinae. Others taxonomists, however, have continued to treat the rhysodids as a distinct family. Regenfuss (1975) and Nagel (1979) suggested that the Rhysodidae could be the sister-group of the remaining Geadephaga; Deuve (1993: 100) the sister-group to the other Adephaga (with the possible exception of Gehringiinae); Beutel and Roughley (1988) the sister-group of the remaining Adephaga excluding Gyrinidae; Beutel (1992a, 1993, 1998) the sister-group to Carabidae (without trachypachids). Recently Makarov (2008) found no evidence from the larval morphology suggesting that rhysodids are specialized Carabidae. Instead rhysodid larvae share several features with those of the suborder Archostemata. At this time, I prefer to rank rhysodids as a distinct family based on tradition but also on the fact that there is no solid morphological or molecular evidence presented to date pointing out that the Carabidae (with or without trachypachids) are paraphyletic in regard to rhysodids.

About 355 species of rhysodids are currently known and are placed into seven family-group taxa, namely Leoglymmiini, Medisorini, Rhysodini, Dhysorini, Sloanoglymmiini, Omoglymmiini, and Clinidiini. These taxa are usually ranked as subtribes when rhysodids are included in the carabids. I have followed Bousquet and Larochelle (1993) in listing them as tribes. Only the last two-mentioned tribes are represented in North America.

Tribe Leoglymmiini. This tribe contains a single species, Leoglymmius lignarius (Olliff), from Australia. Contrary to other rhysodids, the minor setae on antennomeres 5-10 are arranged in broad bands encircling the distal third of the segment and the mentum is separated from the ventral lobe of the gena by a distinct suture in its anterior half.

Tribe Medisorini. A single species, Medisores abditus Bell and Bell, belongs to this tribe. The few known specimens have been found in Cape Province in the Republic of South Africa.

Tribe Rhysodini. This tribe is confined to the Eastern Hemisphere and includes about 25 species in three genera: Rhysodes Germar (two Palaearctic species), Kupeus Bell and Bell (one New Zealand species), and Kaveinga Bell and Bell (23 Australian species).

Tribe Dhysorini. This tribe includes ten species placed in three genera, Dhysores Grouvelle in Africa, Tangarona Bell and Bell in New Zealand, and Neodhysores Bell and Bell in South America.

Tribe Sloanoglymmiini. This tribe has been proposed for one species, Sloanoglymmius planatus (Lea), endemic to southeastern Australia. The genus is taxonomically isolated and its relationship to other rhysodid genera is obscure.

Tribe Omoglymmiini. This tribe includes 180 species placed in eight genera. The group is represented in all zoogeographical regions but less so in Australia, Africa, and South America (Bell and Bell 1978: 66). The two North American species belong to the subgenus Boreoglymmius Bell and Bell, of the genus Omoglymmius Ganglbauer, along with one Japanese species. According to Bell and Bell (1983: 141), the two North American species are probably more closely related to each other than either is to the Japanese species.

Tribe Clinidiini. This tribe contains about 135 species placed in the genera Clinidium Kirby, Rhyzodiastes Fairmaire, and Grouvellina Bell and Bell. The species are found in all zoogeographical regions, including Madagascar, but are absent from the African continent. The North American fauna has only six species, five in the east and one in the west, included in the subgenus Arctoclinidium Bell of the genus Clinidium. This subgenus also contains three Palaearctic species, one in Japan and two in Europe. According to Bell and Bell (1985: 77), the North American species and the Japanese one form a clade and the European species another clade. These authors also placed the Japanese species, Clinidium veneficum Lewis, as the sister-group to Clinidium valentinei Bell of eastern North America.

Family Carabidae. Monophyly of the Carabidae, as defined here, is not evident. The layout of the prehypopharyngeal setae in the larvae (Beutel 1993) and the development of antennal pubescence in the adults (Beutel 1995) have been suggested as synapomorphies for the family. However, Arndt et al. (2005: 138) considered these character states not very convincing given the variation involved in the structures. Recent molecular sequence analyses conducted by Maddison et al. (2009) found little support for monophyly of the group no matter if the trachypachids, rhysodids, and/or cicindelids were included or excluded unless the Carabidae was considered equivalent to the Geadephaga. Therefore, the Carabidae, as defined here, could be paraphyletic in regard to rhysodids, trachypachids, and possibly even to Hydradephaga.

Carabids are found on all continents, except Antarctica, and on most islands. They range from well above the arctic circle to Tierra del Fuego and South Georgia in the Southern Hemisphere. Based on Lorenz’s (2005) checklist, 33, 920 valid species are recognized.

The current classification of the Carabidae is based mainly on morphological data of adults although molecular sequence data have been used recently to discuss various aspects of carabid phylogeny. Despite several attempts there is no consensus on the classification of several subfamilies or tribes. This is particularly evident among ‘basal grade’ carabids.

Fossils belonging to the family Carabidae are known from the early Jurassic (Ponomarenko 1977) which suggests that the family emergence dates back to the beginning of the Jurassic or the end of the Triassic (Kryzhanovskij 1983). Ponomarenko (1977) proposed two family-group taxa of Carabidae among Mesozoic fossils, the subfamily Protorabinae for five genera and the tribe Conjunctiini for two genera.

The world classification of family-group taxa, which has been adopted for the North American fauna in this catalogue, is outlined in Table 3.

Classification of world family-group taxa of Carabidae. Taxa represented in North America are followed by a dot.

| Subfamily Nebriinae | |

| Tribe Pelophilini • | |

| Tribe Opisthiini • | |

| Tribe Nebriini • | |

| Tribe Notiokasiini | |

| Tribe Notiophilini • | |

| Subfamily Cicindinae | |

| Tribe Cicindini | |

| Subfamily Carabinae | |

| Tribe Cychrini • | |

| Tribe Pamborini | |

| Tribe Ceroglossini | |

| Tribe Carabini • | |

| Subfamily Cicindelinae | |

| Tribe Amblycheilini • | |

| Tribe Manticorini | |

| Tribe Megacephalini • | |

| Tribe Cicindelini • | |

| Tribe Ctenostomatini | |

| Tribe Collyridini | |

| Subfamily Loricerinae | |

| Tribe Loricerini • | |

| Subfamily Elaphrinae | |

| Tribe Elaphrini • | |

| Subfamily Omophroninae | |

| Tribe Omophronini • | |

| Subfamily Migadopinae | |

| Tribe Amarotypini | |

| Tribe Migadopini | |

| Subfamily Hiletinae | |

| Tribe Hiletini | |

| Subfamily Scaritinae | |

| Tribe Pasimachini • | |

| Tribe Carenini | |

| Tribe Scaritini • | |

| Tribe Clivinini • | |

| Tribe Salcediini | |

| Tribe Dyschiriini • | |

| Tribe Promecognathini • | |

| Tribe Dalyatini | |

| Subfamily Broscinae | |

| Tribe Broscini • | |

| Subfamily Apotominae | |

| Tribe Apotomini | |

| Subfamily Siagoninae | |

| Tribe Enceladini | |

| Tribe Siagonini | |

| Tribe Lupercini | |

| Subfamily Melaeninae | |

| Tribe Melaenini | |

| Subfamily Gehringiinae | |

| Tribe Gehringiini • | |

| Subfamily Trechinae | |

| Tribe Trechini • | |

| Tribe Zolini | |

| Tribe Bembidiini • | |

| Tribe Pogonini • | |

| Subfamily Patrobinae | |

| Tribe Lissopogonini | |

| Tribe Patrobini • | |

| Subfamily Psydrinae | |

| Tribe Psydrini • | |

| Subfamily Moriomorphinae | |

| Tribe Moriomorphini | |

| Tribe Amblytelini | |

| Subfamily Nototylinae | |

| Tribe Nototylini | |

| Subfamily Paussinae | |

| Tribe Metriini • | |

| Tribe Mystopomini | |

| Tribe Ozaenini • | |

| Tribe Protopaussini | |

| Tribe Paussini | |

| Subfamily Brachininae | |

| Tribe Crepidogastrini | |

| Tribe Brachinini • | |

| Subfamily Harpalinae | |

| Supertribe Pterostichitae | |

| Tribe Morionini • | |

| Tribe Cnemalobini | |

| Tribe Microcheilini | |

| Tribe Chaetodactylini | |

| Tribe Cratocerini | |

| Tribe Abacetini • | |

| Tribe Pterostichini • | |

| Tribe Zabrini • | |

| Tribe Metiini | |

| Tribe Drimostomatini | |

| Tribe Chaetogenyini | |

| Tribe Dercylini | |

| Tribe Melanchitonini | |

| Tribe Oodini • | |

| Tribe Peleciini | |

| Tribe Brachygnathini | |

| Tribe Bascanini | |

| Tribe Panagaeini • | |

| Tribe Chlaeniini • | |

| Tribe Cuneipectini | |

| Tribe Orthogoniini | |

| Tribe Idiomorphini | |

| Tribe Glyptini | |

| Tribe Amorphomerini | |

| Supertribe Harpalitae | |

| Tribe Licinini • | |

| Tribe Harpalini • | |

| Tribe Geobaenini | |

| Tribe Omphreini | |

| Tribe Sphodrini • | |

| Tribe Platynini • | |

| Tribe Perigonini • | |

| Tribe Ginemini | |

| Tribe Enoicini | |

| Tribe Atranini • | |

| Tribe Catapieseini | |

| Tribe Lachnophorini • | |

| Tribe Pentagonicini • | |

| Tribe Odacanthini • | |

| Tribe Calophaenini | |

| Tribe Ctenodactylini • | |

| Tribe Hexagoniini | |

| Tribe Cyclosomini • | |

| Tribe Somoplatini | |

| Tribe Masoreini | |

| Tribe Corsyrini | |

| Tribe Sarothrocrepidini | |

| Tribe Graphipterini | |

| Tribe Lebiini • | |

| Tribe Dryptini | |

| Tribe Galeritini • | |

| Tribe Zuphiini • | |

| Tribe Physocrotaphini | |

| Tribe Anthiini | |

| Tribe Helluonini • | |

| Tribe Xenaroswellianini | |

| Tribe Pseudomorphini • | |

Subfamily Nebriinae. This subfamily includes the tribes Nebriini, Notiokasiini, Notiophilini, Opisthiini, and Pelophilini. All but notiokasiines are Northern Hemisphere elements and represented in North America. Evidence supporting monophyly of Nebriinae is not overwhelming. The only known synapomorphy in the adult stage is the asetose parameres (Kavanaugh and Nègre 1983), a character state found in other, clearly unrelated carabid lineages. Arndt (1993: 21) listed three putative synapomorphies upon examination of the larval morphology. The molecular data analyses by Maddison et al. (1999: 125) provided only moderate support for monophyly of the subfamily and Kavanaugh’s (1998) phylogenetic analysis suggested that this subfamily represents a grade rather than a clade.

The subfamilies Nebriinae and Carabinae could be closely related as pointed out by Jeannel (1940: 7), Bell (1967: 105), Beutel (1992c: 57), and Su et al. (2004: 49). Both groups have open procoxal cavities, contrary to the remaining carabids. In addition, the external lamella of the metepimeron is completely covered and functionally replaced by an extension of the hind margin of the anepisternum (Beutel 1992c: 57). Some authors (e.g., Lorenz 2005: 125) also include the cicindines within the subfamily suggesting a close relationship between these groups. Based on similarities in the genitalia, Deuve (1993: 125) raised the possibility that the Hydradephaga, trachypachids, omophronines, and nebriines form a clade.

Tribe Pelophilini. This tribe includes a single genus, Pelophila Dejean, which has been retained in the tribe Nebriini until recently. Two species are known, both living in the boreal and subarctic regions: one is circumpolar, the other restricted to Canada and Alaska. Kavanaugh (1996: 34) suggested that the genus represents the sister-group to the remaining Nebriinae. One of Kavanaugh’s (1998: Fig. 2) cladograms suggested that Pelophila is more closely related to the tribe Nebriini than are the Opisthiini, Notiophilini, and Notiokasiini.

Tribe Opisthiini. This tribe includes two genera with five species and is doubtless monophyletic. Kavanaugh and Nègre (1983: 564) argued that opisthiines could be the sister-group to the remaining Nebriinae. On the other hand, Kavanaugh’s (1996: Fig. 1A) most parsimonious tree suggested that this tribe is the sister-group to Notiophilini and that these two tribes, along with Notiokasiini, form a clade which represents the sister-group to Nebriini.

Tribe Nebriini. This tribe contains about 600 species in the Palaearctic, Nearctic, and northern parts of the Oriental Regions. However, the group is clearly more diverse in the Palaearctic. The main genera of the tribe are Leistus Frölich, Archastes Jedlička, and particularly Nebria Latreille with more than 60% of the species. The limits of the genus Nebria are not quite settled. Kavanaugh (1995, 1996) regarded Nippononebria Uéno (including Vancouveria Kavanaugh) as the sister-group to Leistus while Ledoux and Roux (2005) listed Nippononebria and Vancouveria as subgenera of Nebria and suggested they form the sister-group to Eonebria Semenov and Znojko and Sadonebria Ledoux and Roux, a complex of 60 Palaearctic species.

Tribe Notiokasiini. This tribe contains a single species, Notiokasis chaudoiri Kavanaugh and Nègre, found in South America. Although the relationships of the tribe are obscure (Kavanaugh and Nègre 1983), Kavanaugh (1996: 33) found 12 synapomorphies supporting monophyly of a clade including notiokasiines, notiophilines, and opisthiines.

Tribe Notiophilini. The tribe includes a single genus, Notiophilus Duméril, very characteristic in the adult stage. The larvae, however, are similar in most structural features to those of Nebriini as pointed out by van Emden (1942). Jeannel (1941b: 175) included Notiophilini, Nebriini (with Pelophila), and Opisthiini in his family Nebriidae, suggesting implicitly a close relationship between the three groups. Kavanaugh’s (1996: Fig. 1A) most parsimonious cladogram suggested a sister-group relationship between Notiophilini and Opisthiini based on adult and larval morphological data. Based on confluent procoxal cavities, Nichols (1985c: Fig. 5) considered the tribe to be the sister-group to {Omophronini + Trachypachini + Hydradephaga}. Erwin (1991a: 11) noted that notiophilines, along with omophronines, hiletines, and trachypachids, have the first mesotarsomere slightly dilated and with squamate setae underneath. However, it remains to ascertain whether this character state is synapomorphic or convergent. Based on female reproductive tracts, Liebherr and Will (1998: 146) suggested that the tribe Notiophilini represents the sister-group to {Opisthiini + Nebriini (with Pelophila) + Omophronini}.

Notiophilines, with about 55 species described to date, live in the Nearctic and Palaearctic Regions and at higher altitudes in the northern parts of the Neotropical and Oriental Regions. They are more speciose in Asia than anywhere else. The phylogenetic relationships of the species have not been studied yet.

Subfamily Cicindinae. This subfamily includes two species, Archaeocindis johnbeckeri (Bänninger) from the Persian Gulf (Kuwait and Iran) and Cicindis horni Bruch from the Córdoba Province of Argentina. Very little can be said at this time about the relationships of the subfamily except that it represents a basal grade carabid taxon. Kryzhanovskij (1976a: 87) associated cicindines with paussines (excluding metriines) and nototylines; Nagel (1979, 1987) and Roig-Juñent et al. (2011) viewed them as the sister-group to paussines. Ball (1979: 100), however, doubted such proposed affinities between cicindines and paussines. Erwin (1985, 1991a), followed by Lorenz (2005: 125), included the Cicindini in the Nebriitae. Kavanaugh and Erwin (1991) studied the structural features and reviewed the relationships of the group. They concluded that cicindines are best placed in a distinct supertribe near the Nebriitae and Elaphritae (sensu Kryzhanovskij 1976a: 88). Kavanaugh’s (1998: Fig. 3) phylogenetic analysis using 153 characters of adult external and male genitalic structures suggested that cicindines may be closely related to omophronines, carabines, cychrines, and cicindelines. Aspects of the behaviour and life history of the Argentine species have been published recently (Erwin and Aschero 2004).