(C) 2013 DeeAnn M. Reeder. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

A new genus is proposed for the strikingly patterned African vespertilionid “Glauconycteris” superba Hayman, 1939 on the basis of cranial and external morphological comparisons. A review of the attributes of a newly collected specimen from South Sudan (a new country record) and other museum specimens of “Glauconycteris” superba suggests that “Glauconycteris” superba is markedly distinct ecomorphologically from other species classified in Glauconycteris and is likely the sister taxon to Glauconycteris. The recent capture of this rarely collected but widespread bat highlights the need for continued research in tropical sub-Saharan Africa and in particular, for more work in western South Sudan, which has received very little scientific attention. New country records for Glauconycteris cf. poensis (South Sudan) and Glauconycteris curryae (Gabon) are also reported.

Glauconycteris superba, Glauconycteris poensis, Glauconycteris curryae, Niumbaha gen. nov. , Badger Bat, South Sudan, Description

In 1939 Hayman described a new vespertilionid bat from the Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), noting that it was “one of the most striking discoveries of recent years’’ (

Glauconycteris, originally described by

Close examination of our 2012 South Sudan specimen relative to other specimens of Glauconycteris superba and of other Glauconycteris species indicates that, while this taxon is probably closely related to species of Glauconycteris, it lacks many of the most notable specializations of that genus, and we suggest that it is sufficiently and remarkably different from other vespertilionids as to warrant placement in a unique genus.

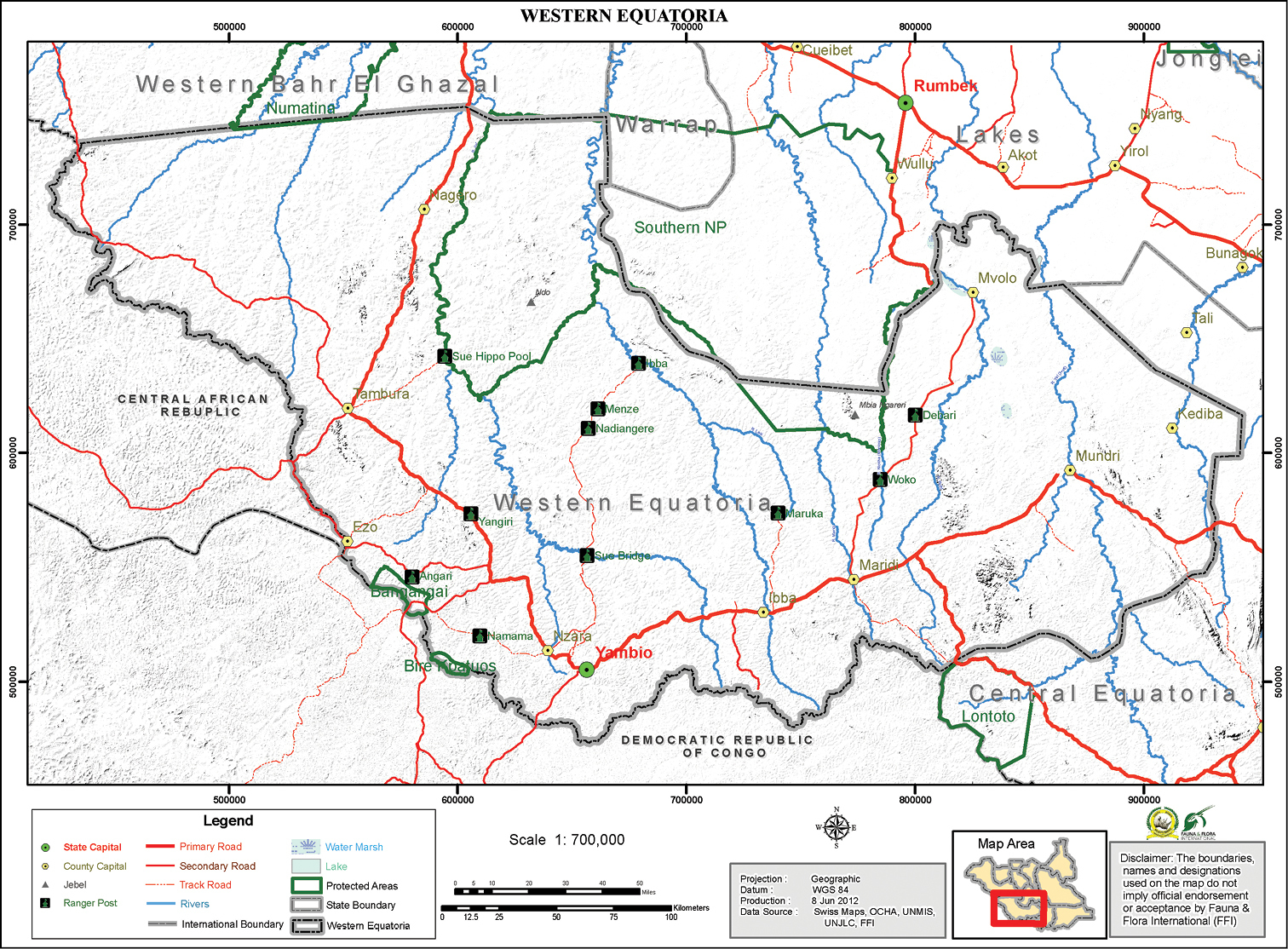

Field work was conducted in Bangangai Game Reserve, Western Equatoria State in the new country of South Sudan in July 2012 (Fig. 1). Bats, including the single “Glauconycteris” superba specimendescribed below and two other species of Glauconycteris, were captured in single ground-height or triple-high mist-nets and euthanized by isoflurane overdose. Tissue samples (liver and muscle) were collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Specimens were either formalin fixed and then transferred to ethanol with skulls extracted or were prepared as skins, skulls, and skeletal material. Field work was approved by the Internal Animal Care and Use Committee of Bucknell University and by the South Sudanese Ministry for Wildlife Conservation and Tourism.

Map of Western Equatoria State, South Sudan. Location of the Bangangai Game Reserve (and the neighboring Bire Kpatuos Game Reserve) and other protected areas shown.

A comparative analysis included data from our 2012 specimens, a few South Sudan specimens from our earlier expeditions, data from the three previously collected specimens of “Glauconycteris” superba and data from museum specimens as noted below. Measurements were taken with rulers (ears) or dial calipers (all other measurements). External and osteological characters examined are based largely upon

Definition of external, craniodental, and mandibular measurements used in this study.

| Measurement | Definition |

|---|---|

| Forearm length (FA) | Distance from the elbow (tip of the olecranon process) to the wrist (including the carpals). |

| Metacarpal length (ML-III, -IV, -V) | Distance from the joint of the wrist (carpals) with the 3rd metacarpal to the metacarpophalangeal joint of the 3rd digit; same for 4th and 5th digits. |

| Phalangeal length (1PL, 2PL) | 1PL: Distance from the metacarphophalangeal joint of each respective digit (DI, DII, DIII) to the phalangeal joint. 2 PL: Distance from the phalangeal joint to the tip of the bone (cartilage tip not included). |

| Greatest length of skull (GLS) | Greatest distance from the occiput to the anteriormost point on the premaxilla. |

| Condyloincisive length (CIL) | Distance between a line connecting the posteriormost margins of the occipital condyles and the anteriormost point on the upper incisors. |

| Condylocanine length (CCL) | Distance between a line connecting the posteriormost margins of the occipital condyles and the anteriormost surfaces of the upper canines. |

| Palatal length | Distance from the posterior palatal notch to the anteriormost border of the incisive alveoli. |

| Zygomatic breadth (ZB) | Greatest breadth across the zygomatic arches. |

| Mastoid width | Greatest breadth at the mastoid processes. |

| Breadth of braincase (BBC) | Greatest breadth of the globular part of the braincase, excluding mastoid and paraoccipital processes. |

| Height of braincase (HBC) | Distance from basisphenoid and basioccipital bones to top of braincase on either side of sagittal crest. |

| Interorbital width | Distance between orbits measured below lachrymal processes. |

| Postorbital process width (POP) | Width across postorbital processes. |

| Postorbital constriction (POC) | Least distance between orbits. |

| Width across M3 (M3-M3) | Greatest width of palate across labial margins of the alveoli of M3s. |

| Maxillary toothrow length (C-M3) | Distance from anteriormost surace of the upper canine to the posteriormost surface of the crown of M3. |

| Width at upper canines (C-C) | Width between labial alveolar borders of upper canines. |

| Greatest length of mandible | Distance from midpoint of condyle to the anteriormost point of the dentary, including the incisors. |

| Mandibular toothrow length (c-m3) | Distance from posterior alveolar border of m3 to the anterior alveolar border of lower canine. |

| Height of the upper canine | Greatest height of the upper canine from point immediately dorsal to cingulum to end of tooth (not taken if tooth too worn). |

| Thickness of the upper canine | Greatest anterior-posterior thickness of the upper canine. |

| Width M3 (WM3) | Greatest lateral-medial width of last tooth (M3). |

| Width M2 (WM2) | Greatest lateral-medial width of second to last tooth (M2). |

| Mid rostrum length (MRL) | Length of a medial line from the inflexion point at the rostrum/braincase to posterior point of emargination in the upper palate. |

| I-M2 alv | Length from anterior alveoli of incisors to posterior alveoli of second to last tooth (M2). |

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:EDF16BEE-0749-41BC-AE19-BAE130BE58F8

http://species-id.net/wiki/Niumbaha

Figures 2–6The name is the Zande word for ‘rare/unusual’. This name was chosen because of the rarity of capture for this genus, despite its wide distribution throughout West and Central Africa, and for the unusual and striking appearance of this bat. Zande is the language of the Azande people, who are the primary ethnic group in Western Equatoria State in South Sudan (where our recent specimen was collected). The homeland of the Azande extends westwards into Democratic Republic of the Congo, where superba has also been collected (the holotype and another recent capture), and into southeastern Central African Republic. Gender: feminine.

Glauconycteris superba Hayman, 1939; by monotypy.

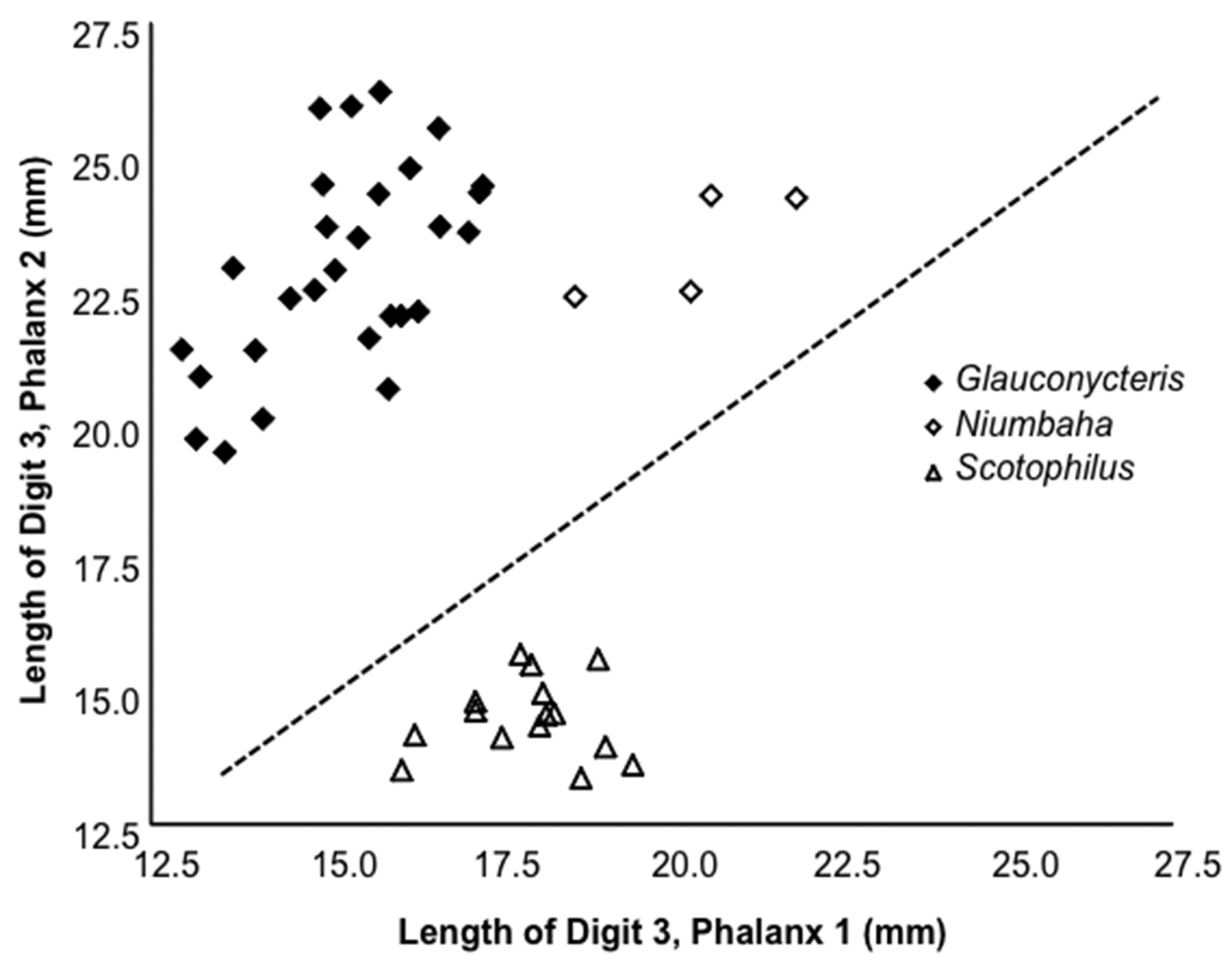

Among vespertilionids, Niumbaha bears closest comparison with species of Glauconycteris (the type species of which is Glauconycteris poensis), to which it is apparently closely related, but it has a considerably larger skull and is more strikingly patterned compared to any member of Glauconycteris (its patterning most closely approaching the Asian vespertilionid genus Scotomanes). It lacks various of the most exaggeratedly derived traits (specializations) that uniquely unite the species of Glauconycteris among African vespertilionids, including the excessively foreshortened rostrum, moderately to highly reduced relative canine size, and very elongate wing tips (second wing phalanxes) of Glauconycteris (

Photographs of Niumbaha superba live and as a freshly prepared specimen. Top photos show profile and anterior view, with ventral and dorsal images below.

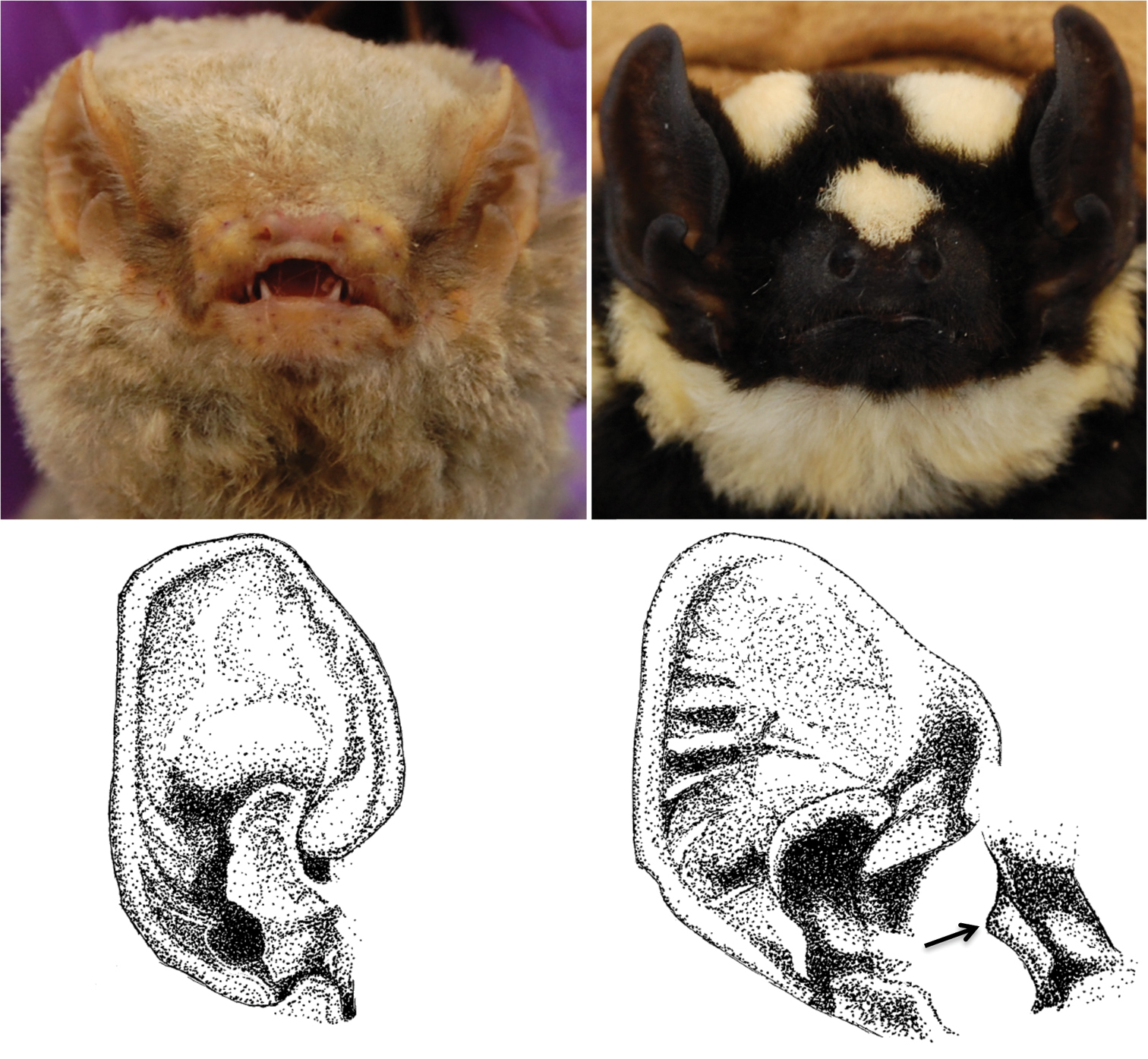

Contrasting facial aspects for Glauconycteris cf. poensis (left) and Niumbaha superba (right). Top panels show differences in nostril shape and orientation from photographs of live bats, bottom drawings show difference in ear and tragus structure. Glauconycteris poensis and Niumbaha superba are the type species of Glauconycteris and Niumbaha.

Length of the 2nd phalanx (2PL) of the 3rd digit vs. the 1st phalanx (1PL) of the 3rd digit. Several species of Glauconycteris are shown (closed diamond), as is Niumbaha superba (open diamond), and for comparison, two species of Scotophilus (open triangle; a ‘typical’ African vespertilionid bat). The ratio of 2PL/1PL is significantly greater in Glauconycteris than in Niumbaha (with a theoretical 1:1 ratio indicated by the dashed line). Data as reported in Table 2.

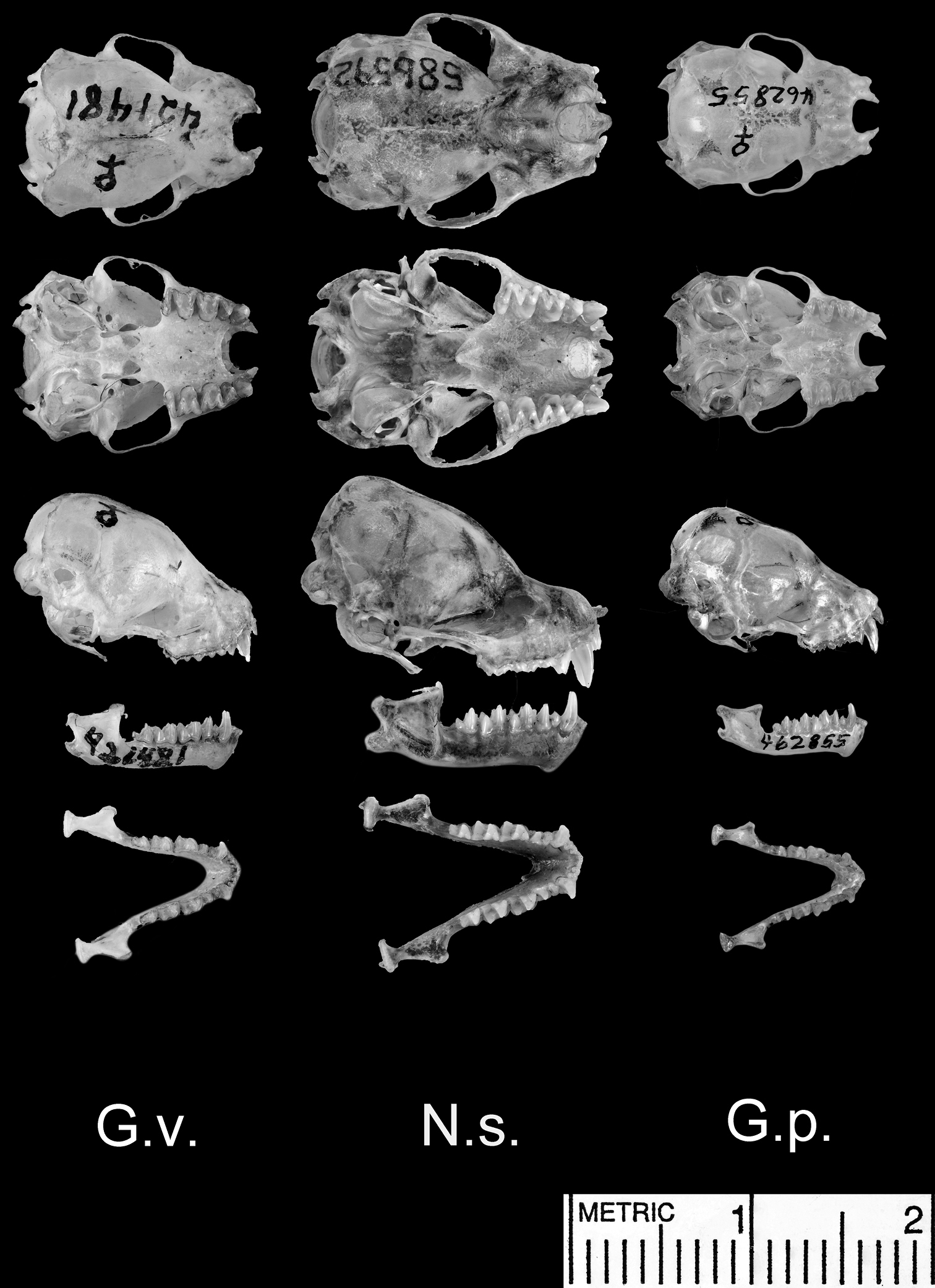

Dorsal and ventral views of the cranium, lateral views of the cranium and mandible, and dorsal view of the mandible. Species shown include Glauconycteris variegata (G.v.; a relatively large species of Glauconycteris, which nearly matches Niumbaha superba in linear body size, but not in skull size); Niumbaha superba (N.s.; the type species of Niumbaha), and Glauconycteris poensis (G.p., the type species of Glauconycteris).

Selected measurements (in mm) of Niumbaha superba and several Glauconycteris and Scotophilus species. Summary statistics (mean and standard deviation), observed range and sample size of measurements are given for each species. See Table 1 for definition of measurement abbreviations and see methods for list of specimens examined.

| Character | Niumbaha superba* | Glauconycteris alboguttata | Glauconycteris argentata | Glauconycteris beatrix | Glauconycteris curryae | Glauconycteris humeralis | Glauconycteris poensis | Glauconycteris cf. poensis | Glauconycteris variegata | Scotophilus leucogaster | Scotophilus viridis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-III | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 44.7 ± 2.3 | 39.8 | 41.7 ± 0.7 | 37.8 ± 1.9 | 35.0 | - | 38.4 ± 1.3 | 42.3 ± 1.1 | 42.3 ± 1.3 | 50.8 ± 1.4 | 46.8 ± 2.5 |

| Min-max | 42.0–47.4 | - | 40.8–42.3 | 35.2–39.6 | - | - | 36.4–39.6 | 40.8–44.3 | 40.5–44.1 | 48.6–52.4 | 41.5–50.1 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| DIII-1PL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 20.4 ± 1.3 | 16.0 | 15.6 ± 0.6 | 13.4 ± 0.9 | 13.6 | - | 13.9 ± 0.9 | 15.6 ± 0.7 | 16.6 ± 0.6 | 18.6 ± 0.5 | 17.1 ± 1.1 |

| Min-max | 18.7–22.0 | - | 15.0–16.3 | 12.3–14.5 | - | - | 12.9–15.2 | 14.9–16.7 | 15.7–17.4 | 18.1–19.6 | 15.7–19.2 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| DIII-2PL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 23.4 ± 1.1 | 22.0 | 25.7 ± 0.6 | 21.3 ± 1.6 | 19.5 | - | 21.3 ± 1.0 | 24.1 ± 0.8 | 22.8 ± 1.4 | 14.6 ± 0.8 | 13.9 ± 1.2 |

| Min-max | 22.4–24.3 | - | 24.8–26.2 | 19.7–22.9 | - | - | 20.1–22.9 | 22.5–25.6 | 20.7–24.5 | 13.4–15.5 | 11.9–15.7 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| ML-IV | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 43.4 ± 2.5 | 35.8 | 39.1 ± 1.1 | 34.1 ± 1.8 | 32.5 | - | 34.9 ± 1.1 | 39.3 ± 1.4 | 40.8 ± 1.3 | 48.9 ± 1.6 | 45.6 ± 2.3 |

| Min-max | 40.6–46.4 | - | 37.7–40.3 | 31.6–36.0 | - | - | 33.6–36.4 | 37.0–41.8 | 39.4–42.5 | 46.4–50.6 | 41.4–48.9 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| DIV-1PL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 13.5 ± 1.2 | 11.8 | 11.7 ± 0.4 | 10.1 ± 0.7 | 8.8 | - | 11.1 ± 0.4 | 11.6 ± 0.7 | 12.7 ± 0.9 | 13.7 ± 1.1 | 13.5 ± 1.0 |

| Min-max | 12.2–15.0 | - | 11.4–12.1 | 9.1–10.8 | - | - | 10.5–11.4 | 10.8–12.2 | 11.2–13.9 | 11.3–15.1 | 12.1–14.8 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| DIV-2PL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 10.1 ± 0.9 | 10.8 | 11.8 ± 0.6 | 11.5 ± 1.1 | 12.0 | - | 10.8 ± 0.9 | 11.6 ± 0.8 | 12.3 ± 0.8 | 10.2 ± 0.3 | 9.1 ± 0.9 |

| Min-max | 9.0–10.8 | - | 11.2–12.4 | 10.1–12.6 | - | - | 9.9–11.9 | 10.6–12.5 | 10.9–13.5 | 9.8–10.7 | 7.2–10.2 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 4 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| ML-V | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 38.8 ± 2.8 | 31.2 | 35.5 ± 0.9 | 32.5 ± 1.2 | 29.9 | - | 32.1 ± 0.8 | 35.5 ± 0.8 | 38.6 ± 1.5 | 47.1 ± 1.6 | 42.9 ± 1.9 |

| Min-max | 35.5–42.0 | - | 34.3–36.3 | 31.3–34.2 | - | - | 30.6–32.8 | 33.7–37.0 | 36.1–40.4 | 43.9–49.4 | 39.5–45.8 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| DV-1PL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 8.8 ± 1.2 | 9.6 | 9.6 ± 0.4 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 8.4 | - | 9.8 ± 0.5 | 10.3 ± 1.0 | 10.6 ± 0.6 | 10.2 ± 0.9 | 9.0 ± 0.6 |

| Min-max | 7.6–10.4 | - | 9.2–10.2 | 8.8–9.7 | - | - | 9.1–10.3 | 9.1–11.4 | 9.7–11.4 | 8.9–11.6 | 7.9–9.6 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| DV-2PL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 7.5 ± 0.7 | 7.8 | 8.7 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.5 | 7.6 | - | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 8.3 ± 0.9 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.7 |

| Min-max | 6.8–8.2 | - | 8.3–9.5 | 6.8–7.9 | - | - | 7.5–8.8 | 6.7–8.4 | 7.2–9.8 | 5.9–6.9 | 5.7- 7.4 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| DIII-2PL/1PL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.4 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.4 | - | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.01 |

| Min-max | 1.1–1.2 | - | 1.5–1.7 | 1.5–1.7 | - | - | 1.4–1.7 | 1.5–1.6 | 1.3–1.4 | 0.7–0.9 | 0.7–0.9 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| DIV-2PL/1PL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.4 | - | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Min-max | 0.7–0.8 | - | 1.0–1.1 | 1.0–1.3 | - | - | 0.9–1.1 | 0.9–1.1 | 0.9–1.1 | 0.7–0.8 | 0.6–0.8 |

| n | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 4 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| GLS | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 16.8 ± 0.6** | 13.3 | 12.7 ± 0.3 | 11.4 ± 0.2 | 12.2 | 11.1 ± 0 | 12.3 ± 0.3 | - | 13.9 ± 0.3 | 20.5 ± 0.3 | 18.0 ± 0.7 |

| Min-max | 16.2–17.4 | 13.2–13.4 | 12.0–13.3 | 11.2–11.6 | - | 11.1–11.1 | 12.0–12.7 | - | 13.4–14.4 | 20.1–20.9 | 17.0–18.4 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| CIL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 15.6 ± 0.4** | 12.8 | 12.3 ± 0.3 | 11.1 ± 0.3 | 11.1 | 10.9 ± 0.1 | 11.9 ± 0.3 | - | 13.3 ± 0.3 | 18.0 ± 0.2 | 16.3 ± 0.5 |

| Min-max | 15.4–16.2 | 12.7–12.9 | 11.7–12.5 | 10.9–11.5 | - | 10.8–11.0 | 11.5–12.4 | - | 12.8–13.8 | 17.7–18.3 | 15.6–16.6 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| CCL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 16.0 | 12.4 | 11.9 ± 0.4 | 10.9 ± 0.3 | 10.7 | 10.8 ± 0.3 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | - | 12.9 ± 0.3 | 17.5 ± 0.3 | 15.8 ± 0.4 |

| Min-max | - | 12.4–12.4 | 11.0–12.2 | 10.7–11.2 | - | 10.5–11.0 | 11.1–12.0 | - | 12.3–13.4 | 17.1–17.9 | 15.3–16.3 |

| n | 1 | 2 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| Palatal length | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 5.9 ± 0.4** | 5.3 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | - | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | - | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 6.5 ± 0.5 |

| Min-max | 5.5–6.5 | 5.1–5.5 | 4.4–5.3 | 4.3–4.5 | - | 4.4–4.8 | 4.4–5.5 | - | 4.8– 6.0 | 6.9–7.3 | 6.1–7.2 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 13 | 3 | - | 3 | 4 | - | 22 | 7 | 4 |

| ZB | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 11.4 ± 0.5** | 9.5 | 9.0 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 8.5 | 8.2 | 8.6 ± 0.2 | - | 10.2 ± 0.3 | 13.1 ± 0.4 | 12.0 ± 0.4 |

| Min-max | 11.0–11.9 | 9.4–9.5 | 8.6–9.2 | 8.1–8.4 | - | 8.0–8.3 | 8.4–8.9 | - | 9.5–10.9 | 12.7–13.8 | 11.5–12.3 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| Mastoid width | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 9.6 ± 0.2** | 8.4 | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 7.3 | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | - | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 11.5 ± 1.0 | 10.2 ± 0.4 |

| Min-max | 9.5–9.9 | 8.4 – 8.4 | 7.9–8.5 | 7.4–7.6 | - | 7.1–7.4 | 7.5–8.0 | - | 8.4–9.4 | 9.3–12.3 | 9.6–10.5 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| BBC | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 8.7 ± 0.3** | 7.8 | 7.6 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 6.8 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 0.3 | - | 8.0 ± 0.2 | 9.2 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 0.2 |

| Min-max | 8.5–9.0 | 7.7–7.9 | 7.4–8.0 | 6.9–7.0 | - | 6.7–6.9 | 6.8–7.4 | - | 7.6–8.4 | 8.8–9.4 | 8.1–8.5 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| HBC | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 6.9 ± 0.3** | 5.8 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 4.9 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | - | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 6.8 ± 0.5 |

| Min-max | 6.6–7.3 | 5.8 – 5.8 | 5.5–6.0 | 4.9–5.2 | - | 5.0–5.2 | 5.1–5.6 | - | 5.7–6.2 | 7.7–8.6 | 6.1–7.1 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| Interorbital width | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 6.4 ± 0.2** | 5.7 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | - | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 0.3 | 7.1 ± 0.4 |

| Min-max | 6.2–6.7 | 5.6–5.8 | 5.3–5.6 | 4.6–4.7 | - | 4.4–4.7 | 5.1–5.4 | - | 5.6–6.9 | 7.6–8.4 | 6.5–7.3 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| POP | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 6.4 ± .3** | 5.8 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.7 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | - | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 7.9 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.3 |

| Min-max | 6.1–6.9 | 5.8–5.8 | 5.3–5.8 | 4.8–5.0 | - | 4.4–4.9 | 5.1–5.5 | - | 5.7–6.4 | 7.6–8.2 | 6.5–7.3 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| POC | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 4.8 ± 0.1** | 4.7 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.0 | 4.4 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | - | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.2 |

| Min-max | 4.7–5.0 | 4.5–4.8 | 4.5–5.9 | 4.3–4.3 | - | 4.0–4.1 | 3.9–4.4 | - | 4.2–4.8 | 4.6–5.2 | 4.1–4.5 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| M3-M3 | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 8.0 ± 0.3** | 6.5 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 5.6 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | - | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 8.5 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 0.1 |

| Min-max | 7.5–8.2 | 6.4–6.5 | 5.8–6.2 | 5.2–5.7 | - | 5.2–5.3 | 5.5–6.1 | - | 6.6–7.2 | 8.3–8.7 | 7.6–7.9 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| C-M3 | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 6.0 ± 0.2** | 4.4 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 4.0 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | - | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.2 |

| Min-max | 5.8–6.2 | 4.3–4.4 | 3.9–4.2 | 3.8–4.0 | - | 3.7–3.9 | 4.0–4.2 | - | 4.5–5.0 | 6.5–6.7 | 5.7–6.0 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| C-C | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 6.0 ± 0.2** | 4.8 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.5 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | - | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 5.7 ± 0.2 |

| Min-max | 5.8–6.2 | 4.8–4.9 | 4.1–4.5 | 3.9–4.0 | - | 3.6–3.8 | 4.0–4.6 | - | 4.4–5.2 | 6.2–6.6 | 5.4–5.9 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| Mandible | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 12.3 ± 0.5** | 9.6 | 9.0 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 8.2 | 8.6 ± 0.5 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | - | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 14.1 ± 0.3 | 12.7 ± 0.2 |

| Min-max | 11.6–12.7 | 9.6–9.6 | 8.7–9.3 | 8.2–8.5 | - | 8.2–9.1 | 8.4–9.1 | - | 9.8–10.5 | 13.6–14.5 | 12.4–12.9 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| c-m3 | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 6.7 ± 0.2** | 5.0 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4.4 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | - | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.2 | 6.6 ± 0.1 |

| Min-max | 6.4–6.9 | 4.9–5.1 | 4.3–4.9 | 3.9–4.5 | - | 4.0–4.8 | 4.2–4.7 | - | 5.1–5.6 | 7.2–7.7 | 6.5–6.8 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| Height of the upper canine | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 2.8 | 2.2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.4 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | - | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

| Min-max | - | 2.1–2.2 | 1.7–2.1 | 1.2–1.4 | - | 1.1–1.3 | 1.6–1.9 | - | 1.8–2.4 | 2.9–3.9 | 2.9–3.4 |

| n | 1 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 | - | 22 | 7 | 4 |

| Thickness of the upper canine | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0 | - | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| Min-max | - | 0.9–0.9 | 0.5–1.0 | 0.6–0.8 | - | 0.6–0.7 | 0.8–0.8 | - | 0.7–1.0 | 1.4–1.9 | 1.2–1.4 |

| n | 1 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| WM3 | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.4 | 1.3 ± 0 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | - | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 |

| Min-max | - | 1.5–1.5 | 1.4–1.5 | 1.2–1.4 | - | 1.3–1.3 | 1.3–1.4 | - | 1.6–2.0 | 2.1–2.5 | 1.9–2.0 |

| n | 1 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| WM2 | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 ± 0 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | - | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| Min-max | - | 1.6–1.8 | 1.4–1.5 | 1.2–1.3 | - | 1.3–1.3 | 1.4–1.6 | - | 1.6–2.0 | 2.1–2.4 | 2.1–2.4 |

| n | 1 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| MRL | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 2.9 | 2.1 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 2.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | - | - | 2.1 ± 0.2 | - | - |

| Min-max | - | 1.9–2.2 | 1.5–2.4 | 1.4–1.9 | - | 1.5–2.0 | - | - | 1.6–2.5 | - | - |

| n | 1 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | - | - | 23 | - | - |

| I-M2 alv | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 6.8 | 4.9 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | - | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 7.2 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.1 |

| Min-max | - | 4.9–4.9 | 4.2–4.8 | 4.1–4.6 | - | 4.1–4.4 | 4.4–4.8 | - | 4.7–5.4 | 6.9–7.5 | 6.3–6.6 |

| n | 1 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 24 | 7 | 4 |

| Mastoid width/GLS | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 0.57 ± 0.01** | 0.63 | 0.65 ± 0.01 | - | 0.60 | 0.65 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.01 | - | 0.64 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.00 |

| Min-max | 0.56–0.59 | 0.63–0.64 | 0.63–0.67 | - | - | 0.64–0.67 | 0.62–0.64 | - | 0.61–0.66 | 0.46–0.60 | 0.56–0.57 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | - | 1 | 3 | 6 | - | 22 | 7 | 4 |

| BBC/GLS | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 0.52 ± 0.00** | 0.59 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | - | 0.56 | 0.61 ± 0.01 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | - | 0.58 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.02 |

| Min-max | 0.52–0.52 | 0.58–0.60 | 0.58–0.63 | - | - | 0.60–0.62 | 0.56–0.60 | - | 0.55–0.61 | 0.43–0.46 | 0.46–0.47 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | - | 1 | 3 | 6 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

| HBC/GLS | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 0.41 ± 0.01** | 0.44 | 0.45 ± 0.12 | - | 0.40 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | - | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.02 |

| Min-max | 0.41–0.42 | 0.43–0.44 | 0.43–0.47 | - | - | 0.45–0.46 | 0.42–0.45 | - | 0.41–0.45 | 0.38–0.41 | 0.36–0.39 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 11 | - | 1 | 3 | 6 | - | 22 | 7 | 4 |

| ZB/GLS | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 0.71 | 0.71 ± 0.03 | - | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.70 ± 0.02 | - | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 0.64 ± 0.02 | 0.67 ± 0.01 |

| Min-max | 0.67–0.69 | 0.71–0.71 | 0.68–0.77 | - | - | 0.72–0.75 | 0.67–0.73 | - | 0.69–0.77 | 0.62–0.66 | 0.66–0.68 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 10 | - | 1 | 2 | 6 | - | 22 | 7 | 4 |

| C-C/M3-M3 | |||||||||||

| X‾ ± SD | 0.76 ± 0.01** | 0.74 | 0.72 ± 0.02 | - | 0.63 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.76 ± 0.04 | - | 0.70 ± 0.02 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 0.73 ± 0.03 |

| Min-max | 0.74–0.77 | 0.73–0.76 | 0.69–0.76 | - | - | 0.69–0.73 | 0.69–0.82 | - | 0.65- 0.75 | 0.72–0.80 | 0.70–0.77 |

| n | 4 | 2 | 12 | - | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | 23 | 7 | 4 |

* For cranial and dental measurements and ratios, significant size differences (based upon t-tests with p ≤ 0.05) between Niumbaha and Glauconycteris (all measured species combined) are indicated with **.

The collection of a new specimen of Niumbaha superba in South Sudan (USNM 586592) in July 2012 allowed for the examination of a live bat and for the preservation of an intact specimen in fluid. This bat was captured in a single-high ground-level mist net next to a stagnant pool of water on a rocky grasslands plateau. This plateau, located at 04°52.643'N, 027°40.557'E (elevation ~ 720 m) is surrounded by secondary thicket forest and is within the boundaries of Bangangai Game Reserve, Ezo County, Western Equatoria State. Data for previously collected specimens of Niumbaha superba were taken from

Data for Niumbaha superba were compared to those of various species of Glauconycteris, as summarized in Table 2. Additionally, for the wingtip analysis, comparisons with other, more ‘typical’ West African vespertilionids of similar size to Niumbaha superba (Scotophilus leucogaster and Scotophilus viridis) were made. Species/specimens examined: Glauconycteris alboguttata J. A. Allen, 1917 (2): Cameroon (AMNH 236329, USNM 598588); Glauconycteris argentata (Dobson, 1875) (14): Cameroon (AMNH 23624, AMNH 23625, AMNH 23627, AMNH 23628), Democratic Republic of the Congo (AMNH 120328, AMNH 120332, USNM 535398), Kenya (USNM 268759), Tanzania (AMNH 55545, AMNH 55546, AMNH 55548, USNM 297476, USNM 297477, USNM 297478); Glauconycteris beatrix Thomas, 1901 (4): Cameroon (USNM 511928, USNM 511929), Gabon (USNM 584723), Ghana (USNM 420078); Glauconycteris curryae Eger and Schlitter, 2001 (1): Gabon (USNM 584724); Glauconycteris humeralis J.A. Allen, 1917 (3): Democratic Republic of the Congo (AMNH 49014, AMNH 49312, AMNH 49315); Glauconycteris poensis (Gray, 1842) (12): Ivory Coast (USNM 429953, USNM 429954, USNM 429955, USNM 468192), Ghana (USNM 479528, USNM 479529, USNM 479530, USNM 479531, USNM 479533), Nigeria (AMNH 273244), Togo (USNM 437777, USNM 437778); Glauconycteris cf. poensis (6): South Sudan (new country record) (USNM 586596, USNM 586597, USNM 586598, USNM 586599, USNM 586600, USNM 586601), Glauconycteris variegata (Tomes, 1861) (27): Benin (USNM 421480, USNM 421481), Botswana (USNM 518696, USNM 518697), Democratic Republic of the Congo (AMNH 49060, AMNH 49061, AMNH 49062, AMNH 49063, AMNH 49066, AMNH 49067, AMNH 49068, AMNH 49070, AMNH 49195, AMNH 49313), Ghana (USNM 420077, USNM 424900), Kenya (AMNH 238490), Mozambique (USNM 304844), Nigeria (USNM 378863, USNM 378864, USNM 378865), South Africa (AMNH 257397), South Sudan (USNM 586593, USNM 586594, USNM 586595, USNM 590905), Uganda (AMNH 184228); Niumbaha superba (Hayman, 1939) (4): Democratic Republic of the Congo (RMCA 14.765), Ivory Coast (RMCA A9363), Ghana (BMNH 47.10), South Sudan (USNM 586592); Scotophilus leucogaster (Cretzschmar, 1830) (8): Benin (USNM 421421, USNM 421424, USNM 421425), Burkina Faso (USNM 450698, USNM 452887, USNM 452889, USNM 503955), Sierra Leone (USNM 547030); Scotophilus viridis (Peters, 1852) (9): Ivory Coast (USNM 468194, USNM 468195, USNM 468199), Mozambique (USNM 365411, USNM 365412, USNM 365413, USNM 365414, USNM 365417, USNM 365418). Museum abbreviations and information: USNM: National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, (Washington, D.C., USA); AMNH: American Museum of Natural History (New York, USA); BMNH: British Museum of Natural History (London, UK); RMCA: Royal Museum for Central Africa (Tervuren, Belgium).

Species of Glauconycteris are quickly recognized by a variety of distinctive traits, many of which are shared with the monotypic Niumbaha. Below we examine each of these traits, highlighting similarities and differences between Niumbaha and Glauconycteris.

Coloration, pattern, and body size:

In 1947, Hayman described the second specimen collected, this time from the Gold Coast (Ghana) (BMNH 47.10). Hayman found the markings of this specimen sufficiently different from the holotype of superba that he erected a new subspecies based upon it, Glauconycteris superba sheila. The patterning of this specimen differs in that (1) two white spots are found on each shoulder next to the base of the humerus, (2) the unpigmented areas on the upper surface of the elbow, knee and ankle joints are present, and (3) the ventral interfemoral membrane is a pale gray color. Our newly collected specimen more closely resembles the Ghana specimen, but has only one white spot on each shoulder next to the base of the humerus and lacks an unpigmented area at the base of the ankle (Fig. 2). The recent DRC specimen (

Notably, our specimen of Niumbaha superba (and that reported by

Finally, Niumbaha superba is larger than all species of Glauconycteris, as noted by

Wing morphology:

Facial features (including the ear): Glauconycteris is distinctive among African vespertilionids in possessing an extremely shortened but broad muzzle in which the nostrils open more or less to the side from a transverse, thick subcylindrical naked pad. On the underlip is found a thickened pair of pads and the lower lip near the corner of the mouth has a fleshy lappet or fold that can be made to extend horizontally (

The ears of Glauconycteris sensu stricto are of small to moderate size and rounded with a strong semicircular inner margin that ends basally in a “curiously backwardly projecting lobe” and a pronounced antitragus (

Cranial features: Despite placing this bat in Glauconycteris, Hayman (1939:222) noted that the skull was longer and less broad with marked flattening of the rostrum “so that the profile shows an angle at the junction of the brain-case and the rostrum” and (1947:549) and so that there is “considerable lengthening of the infraorbital foramen”; he also noted the presence of proportionally deeper basisphenoid pits (Fig. 5).

Niumbaha shares its dental formula and many dental characteristics with Glauconycteris. The dental formula is 2.1.1.3/3.1.2.3 = 32, but

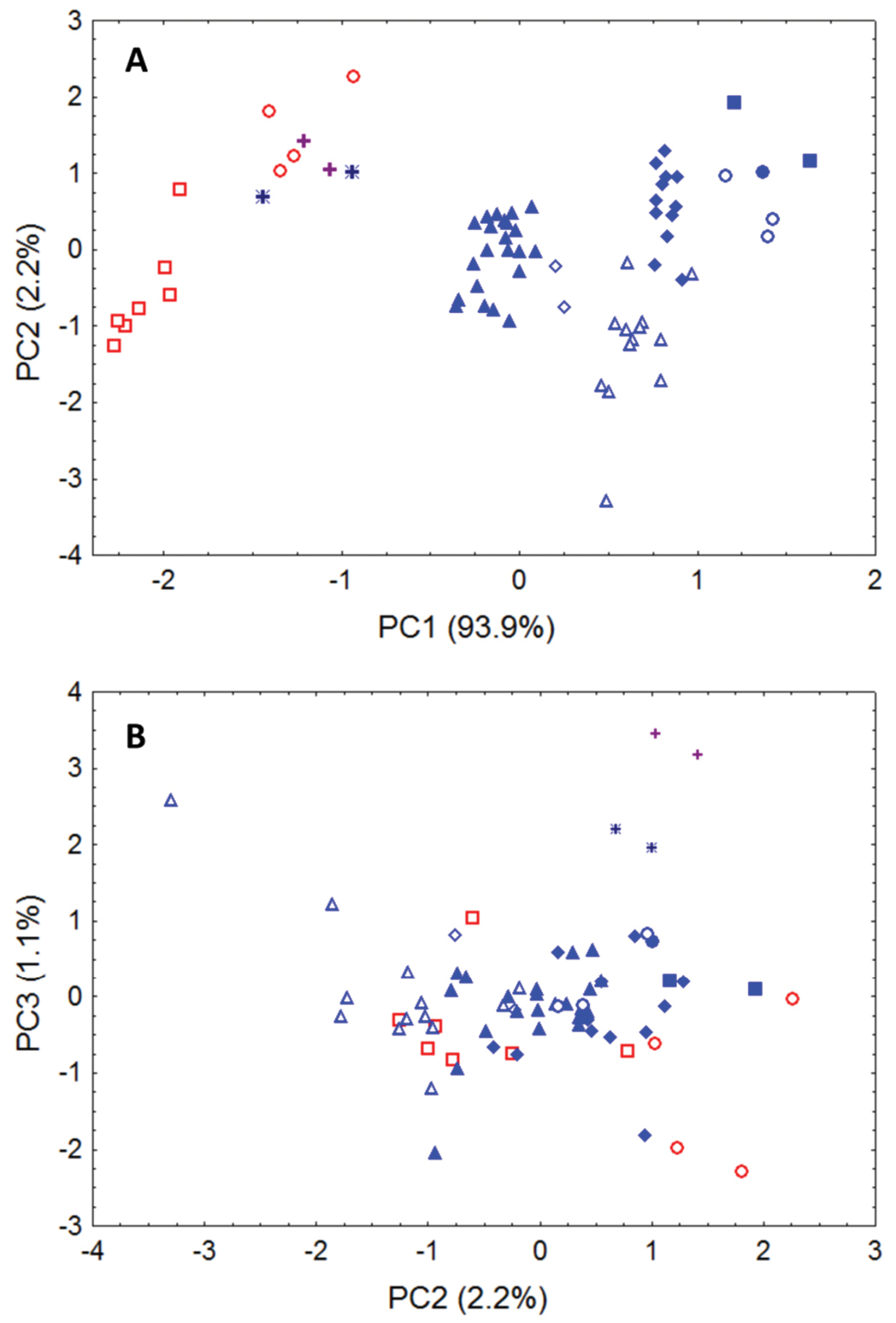

Our principal components analysis of cranial and dental data (based upon measurements listed in Table 2 from Niumbaha, Glauconycteris, and Scotophilus) clearly indicates that the skulls of Niumbaha separate from skulls of species of Glauconycteris, suggesting greater overall ecomorphological resemblance of Niumbaha with medium-sized, less specialized African vespertilionids such as Scotophilus (Fig. 6). The first principal component reflects distinctions in overall skull size and indeed each of the cranial measurements in this analysis is significantly larger for Niumbaha than for Glauconycteris (see Table 2). Beyond size, separation of skulls of Niumbaha from those of Glauconycteris and Scotophilus in combination along the second and third components indicates the morphological isolation of Niumbaha and illustrates consistent differences in skull shape, reflecting (in separation along the third component) the proportionally narrower interorbital dimensions, less dramatic postorbital constriction, longer toothrows, narrowed skull, but widened anterior rostrum in Niumbaha relative to Glauconycteris.

Morphometric separation (first three principal components of a Principal Components Analysis) of 12 cranial and dental measurements. Data are from 70 adult skulls of Glauconycteris, Niumbaha, and Scotophilus (with measurements following Table 1 and 2). Specimens of Scotophilus, included for ecomorphological comparison, are indicated in red (open red squares, Scotophilus leucogaster; open red circles, Scotophilus viridis). Specimens of Glauconycteris are indicated in blue (open blue diamonds, Glauconycteris alboguttata; open blue triangles, Glauconycteris argentata; open blue circles, Glauconycteris beatrix, closed blue circles, Glauconycteris curryae; closed blue squares, Glauconycteris humeralis; closed blue diamonds, Glauconycteris poensis; closed blue triangles, Glauconycteris variegata). Specimens of Niumbaha superba from central Africa (DRC, S Sudan) are marked with crosses; specimens of Niumbaha superba from west Africa (Cote D’Ivoire, Ghana) are marked with asterisks. A Skulls of Niumbaha separate from skulls of species of Glauconycteris in combination along the first and second components, suggesting greater overall ecomorphological resemblance of Niumbaha with medium-sized, less specialized African vespertilionids such as Scotophilus. The first principal component reflects distinctions in overall skull size, which increases from right to left. B Separation of skulls of Niumbaha from those of Glauconycteris and Scotophilus in combination along the second and third components indicates the morphological isolation of Niumbaha and illustrates consistent differences in skull shape, reflecting (in separation along the third component) the proportionally narrower interorbital dimensions, less dramatic postorbital constriction, longer toothrows, narrowed skull, but widened anterior rostrum in Niumbaha relative to Glauconycteris.

Factor loadings, eigenvalues, and percentage of variance explained by illustrated components (Fig. 6) from Principal Components Analysis of 70 adult skulls of Glauconycteris, Niumbaha, and Scotophilus. Principal components were extracted from a covariance matrix of 12 log-transformed cranial measurements (see Table 1, 2).

| Variable | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zygomatic breadth | -0.988 | 0.003 | -0.044 |

| Mastoid width | -0.962 | -0.083 | -0.098 |

| Breadth of braincase | -0.940 | -0.218 | 0.082 |

| Height of braincase | -0.969 | -0.137 | -0.020 |

| Interorbital width | -0.970 | -0.109 | -0.160 |

| Postorbital process width | -0.971 | -0.133 | -0.146 |

| Postorbital constriction | -0.489 | -0.726 | 0.449 |

| Width at M3 | -0.977 | 0.035 | 0.064 |

| Maxillary toothrow length (C-M3) | -0.985 | 0.129 | 0.073 |

| Width at upper canines | -0.966 | 0.054 | 0.091 |

| Greatest length of mandible | -0.989 | 0.077 | 0.012 |

| Mandibular toothrow length | -0.983 | 0.130 | 0.054 |

| Eigenvalues | 0.222 | 0.005 | 0.003 |

| Percent variance (%) | 93.9 | 2.1 | 1.1 |

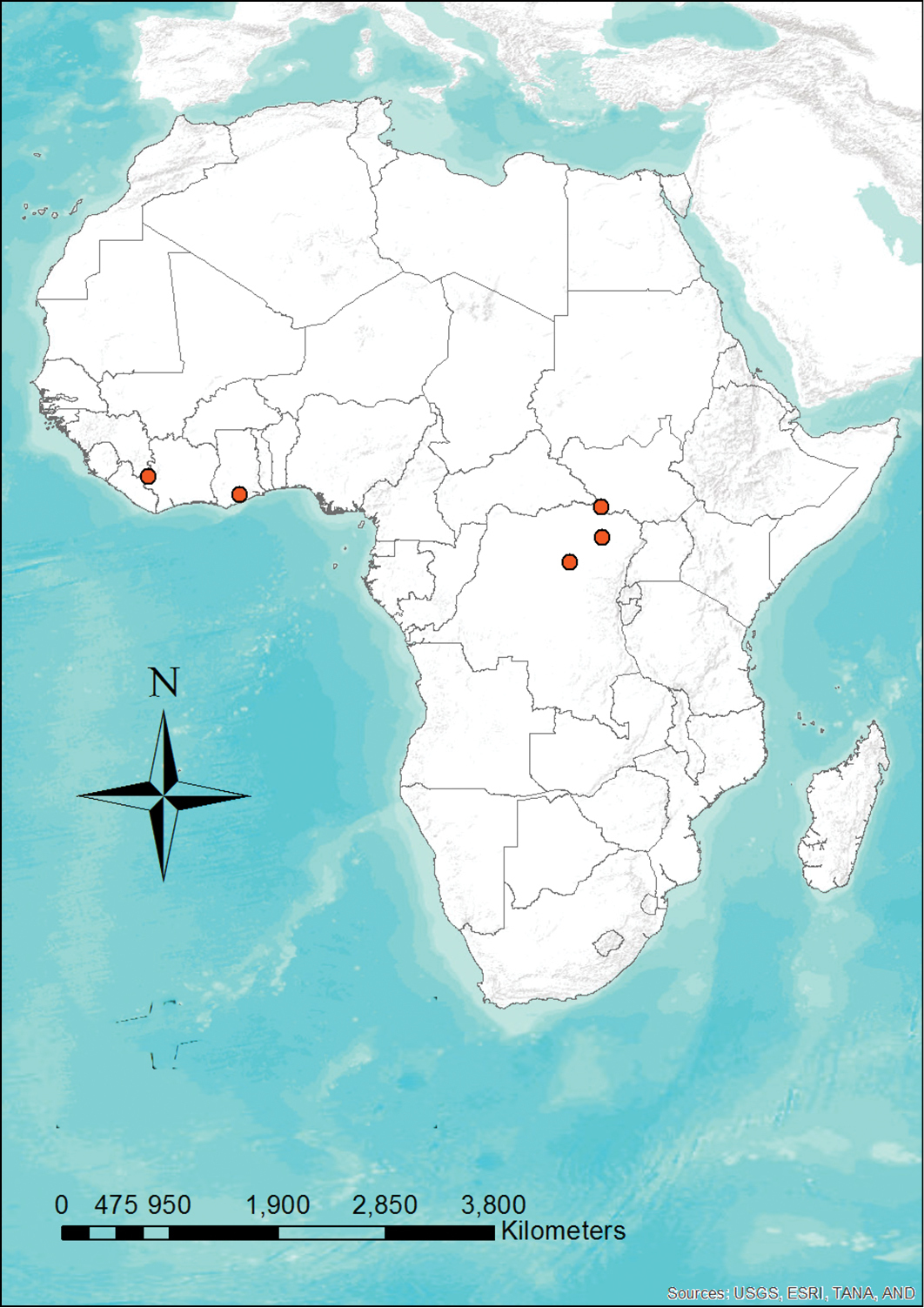

Niumbaha superba has been rarely captured (only five times) but is apparently widely distributed (Fig. 7), being recorded from Ghana, Ivory Coast, Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan. This broad distribution suggests that it is more common than its collection records indicate. Although most species in its apparent sister genus, Glauconycteris, are not well known, at least one species (Glauconycteris variegata) is believed to be a high flier (

Distribution map showing the locations of the five recorded specimens of Niumbaha superba. Given how widely distributed this species is, its rarity in collections is enigmatic.

The generic placement of “Glauconycteris” superba has never been critically reviewed. Only four specimens have previously been mentioned in the literature (

Our naming of a new genus for one of the most extraordinary and rarest-collected bats in Africa highlights a number of issues. Niumbaha superba displays one of the most striking pelage patterns known in bats. While species of Glauconycteris are known for their spots, stripes, and wing reticulation, none are so boldly patterned as Niumbaha superba. Similar markings are found in only a small number of vespertilionids, especially the East Asian Harlequin bat, Scotomanes ornatus, and the western North American Spotted bat, Euderma maculata, as well as in (albeit to a considerably lesser extent) some emballonurids, such as Saccopteryx bilineata.

The conservation status of poorly known species such as Niumbaha superba is difficult to assess. Until 2004, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed Niumbaha superba as “Vulnerable”. In 2008, it changed the listing to “Least Concern” “in view of its wide distribution, presumed large population, and because it is unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for listing in a more threatened category” (

The capture of this bat in South Sudan (as well as the collection of Glauconycteris cf. poensis, a new country record) highlights the need to expand biodiversity surveys and studies in this new nation. These bats were captured in the Bangangai Game Reserve in Western Equatoria State, which resides within a ‘tropical belt’ along the border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is largely composed of dense tropical/subtropical forest, the type of which is highly restricted in South Sudan. Its placement near the Congo Basin ecoregion sets it apart from the rest of South Sudan and elements of the faunas and floras of West Africa and East Africa overlap here (

In his original description of Niumbaha superba,

We are indebted to Matthew Rice and Adrian Garside of Fauna & Flora International (FFI), who provided significant assistance with field logistics in South Sudan and who provided figure 1. Our thanks go to Lauren Helgen of the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH, Smithsonian Institution) for help with photographing specimens, Melissa Meierhofer of Bucknell University for illustrations, Aniko Toth and Paige Engelbrektsson for the distribution map, and to the Woodtiger Fund who graciously provided the funding for the 2012 expedition to South Sudan.