Citation: Maddison DR (2014) An unexpected clade of South American ground beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Bembidion). ZooKeys 416: 113–155. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.416.7706

Phylogenetic relationships of the Antiperyphanes Complex of the genus Bembidion are inferred using DNA sequences from seven genes (two nuclear ribosomal, four nuclear protein coding, and one mitochondrial protein coding). Redefined subgenera within the complex are each well-supported as monophyletic. Most striking was the discovery that a small set of morphologically and ecologically heterogeneous species formed a clade, here called subgenus Nothonepha. This unexpected result was corroborated by the discovery of deep pits in the lateral body wall (in the mesepisternum) of all Nothonepha, a trait unique within Bembidion. These pits are filled with a waxy substance in ethanol-preserved specimens. In one newly discovered species (Bembidion tetrapholeon sp. n., described here), these pits are so deep that their projections into the body cavity from the two sides touch each other internally. These structures in Bembidion (Nothonepha) are compared to very similar mesepisternal pits which have convergently evolved in two other groups of carabid beetles. The function of these thoracic pits is unknown. Most members of subgenus Nothonepha have in addition similar but smaller pits in the abdomen. A revised classification is proposed for the Antiperyphanes Complex.

Carabidae, Bembidiini, Bembidion, phylogeny, systematics, DNA, South America, ground beetles

Ground beetles of the genus Bembidion are distributed throughout the temperate regions of the world (

The Antiperyphanes Complex is a clade restricted to South and Central America. Eight subgenera are considered to belong to the complex (

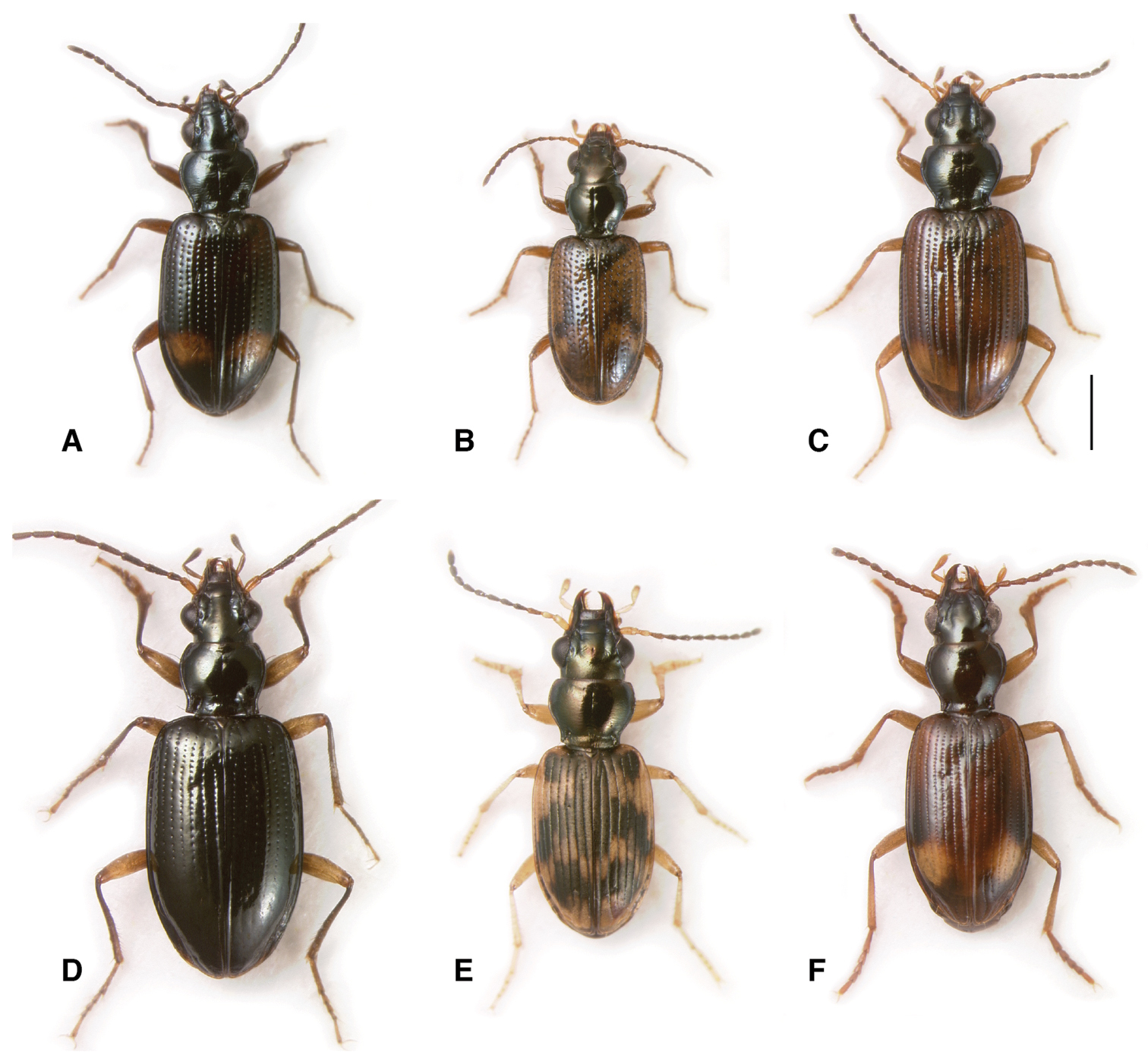

Adults of subgenera Antiperyphanes and Chilioperyphus. A Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) rufoplagiatum. Argentina: Neuquén: Arroyo Queñi at Lago Queñi, DRM voucher V100796 B Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) hirtipes, Argentina: Mendoza: Pampa Palauco, DRM voucher V100792 C Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) spinolai, Argentina: Chubut: Rio Azul at Lago Puelo, DRM voucher V100788 D Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) zanettii, Ecuador: Napo: Rio Quijos W of Baeza, DRM voucher V100791 E Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) mandibulare. Chile: Reg. X, Chiloé: Cucao, DRM voucher V100789 F Bembidion (Chilioperyphus) orregoi, Argentina: Chubut: Rio Azul at Lago Puelo, DRM voucher V100674. Scale bar 1 mm.

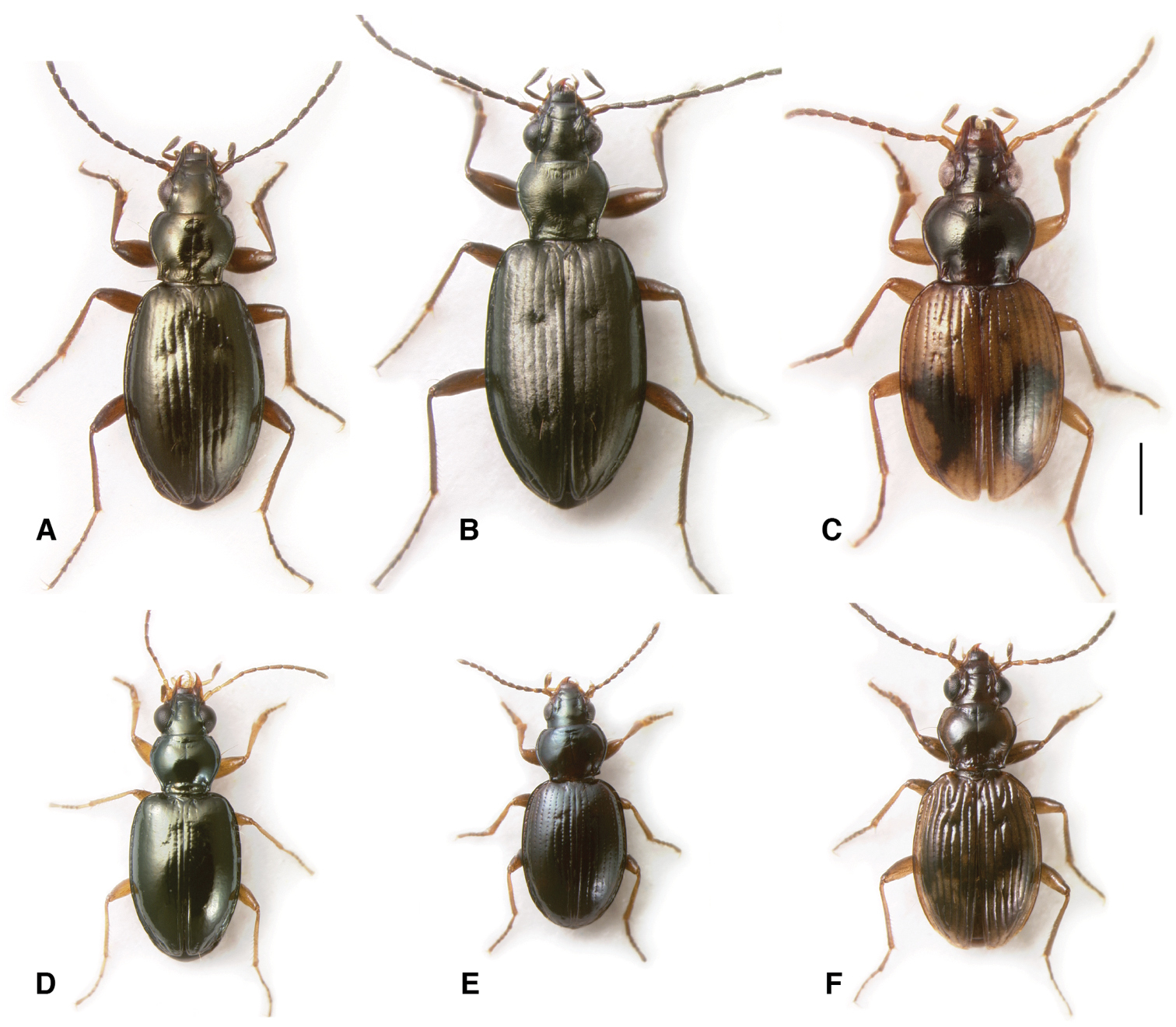

Adults of subgenera Antiperyphus and Notholopha. A Bembidion (Antiperyphus) philippii, Argentina: Neuquén: Rio Collón Curá ca 13 km S La Rinconada, DRM voucher V100787 B Bembidion (Notholopha) scitulum, CHILE: Reg. VII: Los Niches E of Curicó, DRM voucher V100790 C Bembidion (Notholopha) sexfoveolatum, CHILE: Reg. IX: 16.3 km E Malalcahuello, Cuesta Las Raices, DRM voucher V100598. Scale bar 1 mm.

Adults of subgenus Ecuadion. A Bembidion chimborazonum, ECUADOR: Pichincha: Paso de la Virgen, DRM voucher V100793 B Bembidion sanctaemarthae, ECUADOR: Napo: Rio Chalpi Grande, DRM voucher V100798 C Bembidion andersoni, ECUADOR: Pichincha: Reserva Yanacocha, start Andean Snipe Trail, DRM voucher V100655 D Bembidion walterrossi, ECUADOR: Napo: Vinillos, 4.1 km S Cosanga, DRM voucher V100794 E Bembidion cotopaxi, ECUADOR: Pichincha: km 17 on route 28 W of Papallacta DRM voucher V100797 F Bembidion ricei, ECUADOR: Napo: Rio Chalpi Grande, DRM voucher V100622. Scale bar 1 mm.

Habitats of the Antiperyphanes Complex. A River shore, Argentina: Neuquén: Rio Collón Curá, about 13 km S La Rinconada, 625m. On the sandy bank in the foreground Bembidion philippii is abundant, as is Bembidion (Nothonepha) sp. nr. lonae. Also occurring on the sand banks are Bembidium orregoi and Bembidion (Nothonepha) eburneonigrum. On the upper sand banks across the river are Bembidium mandibulare, and in the gravel are Bembidium spinolai B Edges of snowfields at Chile: Reg. IX: Volcán Lonquimay, 1910m. Habitat of Bembidion (Notholopha) sexfoveolatum C Open high-elevation grassland at Ecuador: Pichincha: Paso de la Virgen, 4060m, habitat of three species of subgenus Ecuadion: Bembidion chimborazonum, Bembidion guamani, and Bembidion humboldti D Leaf litter in cloud forest, Ecuador: Pichincha: Reserva Yanacocha, 0.1152°S, 78.5837°W, 3540m, habitat of Bembidion andersoni, Bembidion georgeballi, and Bembidion onorei.

Although monophyly of the Antiperyphanes Complex is well supported (

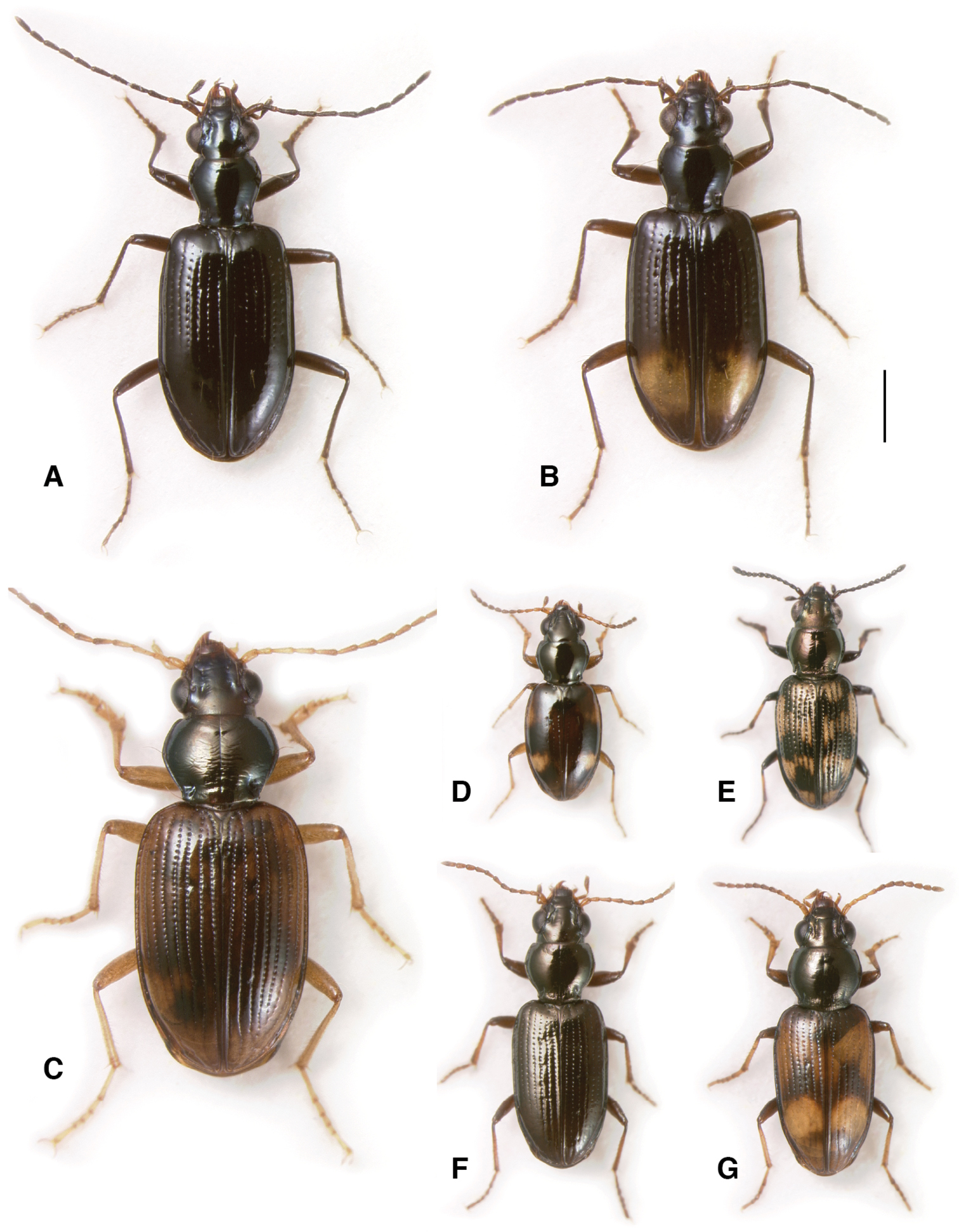

The current more in-depth investigation into phylogeny of the Antiperyphanes Complex was inspired by discovery, on the gravel shores of Rio Puntra on Isla Grande de Chiloé, Chile, of a large, distinctive, undescribed species of Bembidion (Figs 5A and 5B). This unusual species appeared to fall outside any named subgenus, and is given the name Bembidion tetrapholeon in this paper. In order to infer its relationships, additional members of the Antiperyphanes Complex were gathered and sequenced. Preliminary results from the sequences of one gene indicated the existence of a clade so surprising that I initially considered it fallacious, a result of errors in sample labeling, but when additional samples and genes provided stronger support, that explanation was no longer tenable. This apparent clade, including the new species, consisted of taxa that are much more diverse in form (Fig. 5) and habitat (Fig. 6) than other small clades of similar molecular diversity. This paper reports the results of sequencing of seven genes which together provide very strong support for this clade. The discovery of the clade led to the search for morphological synapomorphies of its members, and a striking, derived character was found in thoracic structure. Although the focus of the paper is on this unexpected clade, the relationships of other members of the Antiperyphanes Complex are explored, and a new classification is proposed for the group.

Adults of subgenus Nothonepha. A Bembidion tetrapholeon (black form), Argentina: Neuquén: Arroyo Queñi at Lago Queñi, DRM voucher V100781 B Bembidion tetrapholeon (orange form), Argentina: Chubut: Rio Azul at Lago Puelo, DRM voucher V100780 C Bembidion germainianum, Argentina: Neuquén: Rio Salado at route 40, DRM voucher V100782 D Bembidion lonae, Argentina: Mendoza: Salinas del Diamante, DRM voucher V100786 E Bembidion eburneonigrum, Argentina: Neuquén: Rio Neuquén at Chos Malal, DRM voucher V100785 F Bembidion tucumanum, Argentina: Mendoza: Salinas del Diamante, DRM voucher V100783 G Bembidion engelhardti engelhardti, Argentina: Neuquén: Rio Salado at route 40, DRM voucher V100784. Scale bar 1 mm.

Habitats of the subgenus Nothonepha. A Habitat of Bembidion (Nothonepha) eburneonigrum (on sand patches) and Bembidion (Nothonepha) sp. nr. lonae (on sand patches and in gravel). This habitat (Chile: Reg. IX: Rio Allipén at route 119, 132m) is also home to Bembidion spinolai Solier and Bembidion rufoplagiatum B Habitat of Bembidion (Nothonepha) tucumanum, Bembidion (Nothonepha) lonae, and Bembidion (Nothonepha) engelhardti (Argentina: Mendoza: Salinas del Diamante, 1280m). The beetles are common under rocks and around vegetation on the salt-encrusted clay and sand banks of this saline pond; in the same habitat Bembidion (Notaphus) cillenoides Jensen-Haarup and two other Notaphus are common C On the sand shores of this desert river Bembidion (Nothonepha) germainianum, Bembidion (Nothonepha) engelhardti, and Bembidion (Nothonepha) lonae are common (Argentina: Neuquén: Rio Salado at route 40, 725m) D Type locality of Bembidion (Nothonepha) tetrapholeon (Argentina: Neuquén: Arroyo Queñi at Lago Queñi, 830m). The beetles are found under rocks along the river shore; Bembidion rufoplagiatum is also common in this habitat.

Specimens examined and depositories. Specimens examined are from or will be deposited in the collections listed below. Each collection’s listing begins with the coden used in the text.

BMNH The Natural History Museum, London, UK

CMNH Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

CTVR Luca Toledano collection, Verona, Italy

EMEC Essig Museum Entomology Collection, University of California, Berkeley, USA

IADIZA Instituto Argentino de Investigaciones de las Zonas Aridas, Mendoza, Argentina

MACN Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia”, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

MNHN Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France

MNNC Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Santiago, Chile

NHMW Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Austria

OSAC Oregon State Arthropod Collection, Oregon State University, Corvallis, USA

USNM National Museum of Natural History, Washington, USA

ZMUC Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Collecting methods. Specimens were collected by hand or using an aspirator; specimens were found during the day in their habitat after splashing the soil with water, or with the aid of a headlamp at night, when the beetles are more actively moving on the surface.

Most specimens were killed and preserved in Acer sawdust to which ethyl acetate was added. Specimens collected specifically for DNA sequencing were killed and stored in 95% or 100% ethanol, with best results obtained when the abdomen was slightly separated from the rest of the body to allow better penetration, or when the reproductive system was dissected out through the rear of the abdomen within a few minutes of the beetle’s death in ethanol. Ethanol was decanted and refilled at least two times within the first few weeks after death. Storage was then at 4° or -20°C.

Taxon sampling for DNA studies. DNA was newly sequenced from 25 species of the Antiperyphanes Complex of Bembidion; to these sequences were added sequences of 20 more species of this complex acquired during previous studies (Table 1). Forty additional species of Bembidion were also included in the analyses (27 species of the Bembidion Series exclusive of the Antiperyphanes Complex, plus 13 species of Bembidion outside the Bembidion Series). The 27 additional Bembidion Series species are evident in Fig. 7; details about these species and specimens sequenced are available in

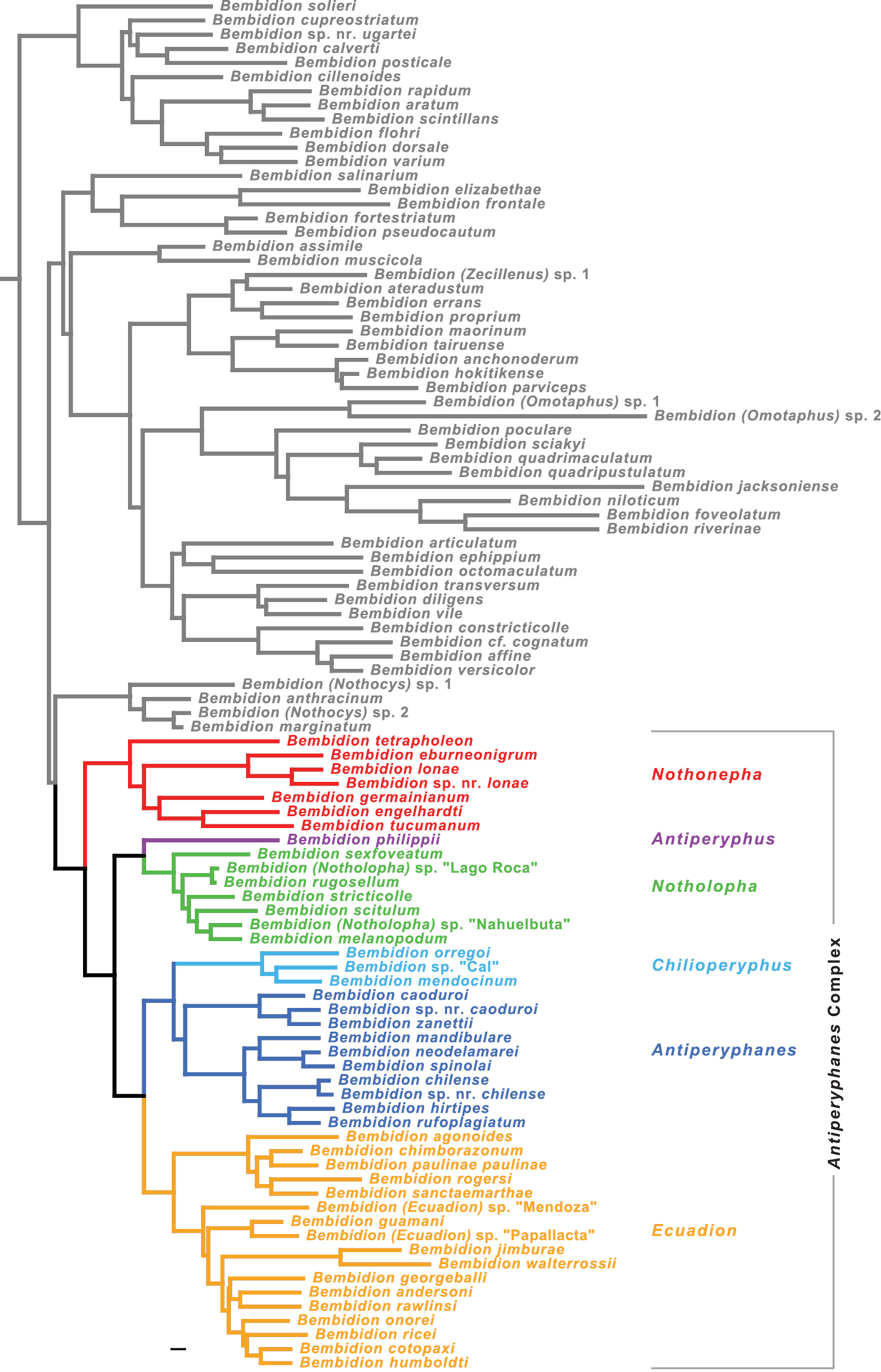

Tree of highest likelihood found for the combined, seven-gene matrix with partitioning scheme chosen by PartitionFinder. Only members of the Bembidion Series shown; more distant outgroups not depicted. Scale bar: 0.01, branch lengths as reconstructed by RAxML.

Sampling of Bembidion species of the Antiperyphanes Complex. The ID column indicates how the specimens were identified: if there is a number in square brackets, then the specimen was identified by me using one of the following references: 1:

Nine additional specimens of Bembidion tetrapholeon sp. n., were sequenced (Table 2) to examine variation. The 10 specimens sequenced in total included specimens from two localities in Chile and three localities in Argentina (Tables 1, 2), and included the typical uniformly black specimens, and others that have a large orange spot on their elytra.

Additional sampling of Bembidion tetrapholeon to examine DNA sequence variation. The DNA voucher number is listed in the “#” column. Color of elytra: BL: nearly black; OR: black with large orange spot. * indicates the holotype. Further details about the localities are provided under the description of Bembidion tetrapholeon and in the Appendix 1. All of these are “genseq-2” sequences (

| # | Color | CAD | wg | ArgK | Topo | 28S | COI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1752 | BL | KJ653110 | KJ653213 | KJ653179 | KJ653047 | KJ653143 | |

| 2356* | BL | KJ653112 | KJ653215 | KJ653082 | KJ653181 | KJ653049 | KJ653145 |

| 2357 | OR | KJ653113 | KJ653216 | KJ653083 | KJ653182 | KJ653050 | KJ653146 |

| 2562 | BL | KJ653115 | KJ653217 | KJ653084 | KJ653184 | KJ653052 | KJ653148 |

| 2566 | BL | KJ653119 | KJ653218 | KJ653085 | KJ653188 | KJ653056 | KJ653152 |

| 2555 | OR | KJ653114 | KJ653183 | KJ653051 | KJ653147 | ||

| 2564 | OR | KJ653117 | KJ653186 | KJ653054 | KJ653150 | ||

| 2565 | BL | KJ653118 | KJ653187 | KJ653055 | KJ653151 | ||

| 2563 | BL | KJ653116 | KJ653185 | KJ653053 | KJ653149 |

Vouchers are housed in the David Maddison voucher collection at Oregon State University, with the exception of voucher number DNA2356, the holotype of Bembidion tetrapholeon, which is deposited in IADIZA.

DNA sequencing. The genes studied, and abbreviations used in this paper, are: 28S or 28S rDNA: 28S ribosomal DNA; 18S or 18S rDNA: 18S ribosomal DNA; ArgK: arginine kinase; CAD: carbamoyl phosphate synthetase domain of the rudimentary gene; COI: cytochrome oxidase I; Topo: topoisomerase I; wg: wingless.

Fragments for these genes were amplified using the Polymerase Chain Reaction on an Eppendorf Mastercycler Thermal Cycler ProS, using TaKaRa Ex Taq and the basic protocols recommended by the manufacturer. Primers and details of the cycling reactions used are given in

Assembly of multiple chromatograms for each gene fragment and initial base calls were made with Phred (

Sequences of COI for two species showed evidence of nuclear copies of this mitochondrial gene (“numts”) (

Alignment and data exclusion. The appropriate alignment was obvious for all protein-coding genes. There were no insertion or deletions (indels) evident in the sampled CAD, ArgK, Topo, or COI sequences. In wingless, there were two small, well-separated indels, restricted to only three taxa: three inserted nucleotides in Bembidion (Zemetallina) parviceps Bates, and six inserted nucleotides in a different region in the two species of subgenus Omotaphus Netolitzky sampled. These inserted nucleotides were excluded from analyses.

The ribosomal genes showed a slightly more complex history of insertions and deletions. Both genes were first subjected to multiple sequence alignment in MAFFT version 7.130b (

Molecular phylogenetic analysis. Models of nucleotide evolution were chosen with the aid of jModelTest version 2.1.1 (

Likelihood analyses of nucleotide data were conducted using RAxML version 7.2.6 (

Most-parsimonious trees (MPTs) were sought using PAUP* (

Morphological methods. General methods of specimen preparation for morphological work, and terms used, are given in

An examination of external and internal features of the exoskeleton was conducted to search for possible apomorphies of one of the discovered clades, focusing on externally-visible pits in the mesothorax and anterior region of the abdomen. Internal skeletal elements were studied on specimens whose soft tissue was dissolved by placing the opened body in a 10% KOH solution at 65 °C for 10 minutes.

Studies of muscles and other internal soft tissue were conducted on specimens killed and preserved in 100% ethanol. This is not the ideal preservation medium, as it leaves muscles brittle and more difficult to trace. However, since the unexpected discovery of structures requiring internal examination, better-fixed specimens have not been available.

Photographs of body parts were taken with a Leica Z6 and JVC KY-F75U camera. For pronotal, elytral, and genitalic images, a stack of photographs at different focal planes was taken using Microvision’s Cartograph software; these TIFF images were then merged using the PMax procedure in Zerene Systems’s Zerene Stacker; the final images thus potentially have some artifacts caused by the merging algorithm.

Sequences have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers KJ653019 through KJ653220. GenBank numbers for the two apparent numts sequences are KJ653155 for DNA2661 and KJ653156 for DNA2650. Aligned data for each specimen as well as files containing inferred trees for each gene and concatenated matrices are available in Suppl. material 1 and 2, and have been deposited in the Dryad Digital Repository, http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.47r16.

The inferred phylogeny is presented in Figs 7 and 8, with support values for notable clades given in Table 3. Maximum likelihood trees and maximum likelihood bootstrap trees for each gene and the concatenated matrices are illustrated in Suppl. material 3 and 4. They are also contained in the NEXUS file S1 in the Suppl. material 1.

Maximum likelihood bootstrap tree showing only those clades appearing in 90% of the bootstrap replicates; taxa outside of the Antiperyphanes Complex not shown. Numbers below branches indicate maximum likelihood bootstrap percentage / parsimony bootstrap percentage. Circled letters on branches correspond to groups documented in Table 3.

Support for and against various clades. The letter at the left corresponds to the circled letters of clades in Fig. 8 (although clade i, consisting of clades j and k, is absent in Fig. 8). ML: Maximum likelihood analysis; P: parsimony analysis. Numbers indicate the bootstrap support expressed as a percentage. Cells shaded in gray to black indicate that the clade is present with bootstrap support greater than 50 or present in the optimal (maximum likelihood or most parsimonious) trees but with bootstrap value below 50. Cells in white indicate that the clade has a bootstrap value less than 50 and is not present in the optimal tree; if the bootstrap value is listed in parentheses, it means that a contradictory clade was present in the optimal trees. For no analysis was there bootstrap support greater than 50 against any of these clades. Abbreviations: “exc.” = “excluding”.

| Clade | Combined | CAD | wg | ArgK | Topo | 28S | 18S | COI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML | P | ML | P | ML | P | ML | P | ML | P | ML | P | ML | P | ML | P | ||

| a | Antiperyphanes Complex | 98 | 94 | 88 | 86 | 27 | 19 | (4) | 1 | (1) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (2) | 1 | (0) | (0) |

| b | Nothonepha | 100 | 100 | 97 | 92 | 69 | 70 | (1) | 0 | (2) | 1 | 50 | 34 | 79 | 59 | (0) | (0) |

| c | Nothonepha exc. Bembidion tetrapholeon | 95 | (48) | 81 | 71 | 55 | 62 | 42 | 43 | (1) | 1 | (9) | 7 | 46 | 40 | (0) | (0) |

| d | Antiperyphanes Complex exc. Nothonepha | 100 | 99 | 80 | 79 | (15) | 20 | 38 | 22 | (3) | 9 | 81 | 75 | 54 | 23 | (0) | 0 |

| e | Antiperyphus + Notholopha | 100 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 78 | 70 | 8 | 2 | (20) | 20 | (1) | 3 | (8) | 46 | (0) | (0) |

| f | Notholopha | 100 | 100 | 63 | 80 | 83 | 81 | 16 | 43 | 43 | 53 | (2) | 3 | 72 | 68 | 49 | 63 |

| g | Antiperyphanes + Chilioperyphus + Ecuadion | 100 | 100 | 97 | 97 | 22 | 32 | (1) | 0 | (29) | 45 | 65 | 53 | 65 | 34 | (0) | 0 |

| h | Antiperyphanes + Chilioperyphus | 100 | 100 | 99 | 99 | 48 | 57 | (7) | 3 | 61 | 60 | 65 | 71 | 87 | 70 | (0) | 0 |

| i | Antiperyphanes | 68 | 71 | 54 | 59 | (15) | 16 | (6) | 7 | 33 | 58 | 68 | 73 | 75 | 62 | (0) | 0 |

| j | Bembidion caoduroi group | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95 | 96 | 98 | 98 | 96 | 96 | 93 | 92 | 66 | 57 | 62 | 57 |

| k | Antiperyphanes exc. Bembidion caoduroi group | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 96 | 97 | 32 | 32 | 61 | 77 | 94 | 91 | (38) | 34 | (29) | 12 |

| l | Ecuadion | 100 | 100 | 54 | 46 | 47 | 53 | 44 | 33 | 66 | 59 | 99 | 100 | 55 | 43 | (2) | 0 |

| m | Bembidion chimborazonum group | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 53 | 56 | 95 | 95 | 97 | 93 | 68 | 68 | 93 | 90 | 17 | 11 |

| n | Ecuadion exc. Bembidion chimborazonum group | 100 | 100 | 46 | 33 | (38) | 5 | (23) | 21 | 46 | 39 | 99 | 99 | 89 | 83 | (1) | 0 |

The monophyly of each subgenus (indicated by color in Figs 7 and 8) is well supported by analyses of the concatenated matrix (MLB=100 and PB=100 for all but one subgenus) and at least four genes (Table 3), except for subgenus Antiperyphanes. Antiperyphanes is monophyletic in the maximum likelihood trees of four genes, but bootstrap support is low (Table 3).

The basal split in the Antiperyphanes Complex appears to be between clade b and clade d (Fig. 8). Clade b is strongly supported in seven-gene analyses (MLB=100, PB=100), and there is bootstrap support in individual analyses of four genes (Table 3). As a subgenus of Bembidion, this clade would take the name Nothonepha Jeannel, as it contains Bembidion lonae, the type species of Nothonepha. Clade d is also strongly supported in the seven-gene analyses (MLB=100, PB=99), and there is moderate to weak bootstrap support from four genes (Table 3).

Within the Antiperyphanes Complex, strongly supported relationships between subgenera include a clade containing Antiperyphanes and Chilioperyphus, and a sister-group relationship between that clade and the subgenus Ecuadion (Fig. 8, Table 3). Bembidion (Antiperyphus) philippii appears as the sister group to subgenus Notholopha.

As a whole, the Antiperyphanes Complex is supported as monophyletic (clade a in Figs 7 and 8, Table 3), although not as strongly as in an earlier study with more limited sampling of the group (

Different analytical methods yielded similar results for the concatenated, seven-gene matrices. The two partition schemes examined (by gene and as chosen by PartitionFinder) resulted in maximum likelihood trees that differ only in the placement of Bembidion georgeballi within subgenus Ecuadion. In maximum likelihood bootstrap analyses, clades with MLB>90 were the same in both partition schemes. Parsimony analyses showed similar results to maximum likelihood (Table 3).

Within Bembidion tetrapholeon sp. n., the 10 specimens sequenced from five localities showed little variation in DNA, and the variation observed was not correlated with presence of an orange spot. There was no variation observed in CAD (n=10), ArgK (n=5), Topo (n=10), and 28S (n=10), over a total of more than 3090 bases. In the wingless gene (n=6) variation was observed at three third-position sites, all of which represent synonymous differences, and for each of which some other specimens were heterozygous for the variants. COI showed the most variation with variability at eight sites, seven of which represented synonymous differences and one a non-synonymous difference. At seven of these sites, nine of the ten specimens had the same nucleotide, with the tenth specimen being unique; the specimen that was unique varied from site to site. The most distinct specimen was DNA2236, from Chiloé, with three unique nucleotides in the more than 650 bases of COI sequenced.

With the unexpected discovery that Bembidion tetrapholeon sp. n., belongs in a clade with an assortment of morphologically and ecologically diverse Bembidion, the search for synapomorphies for this clade became compelling.

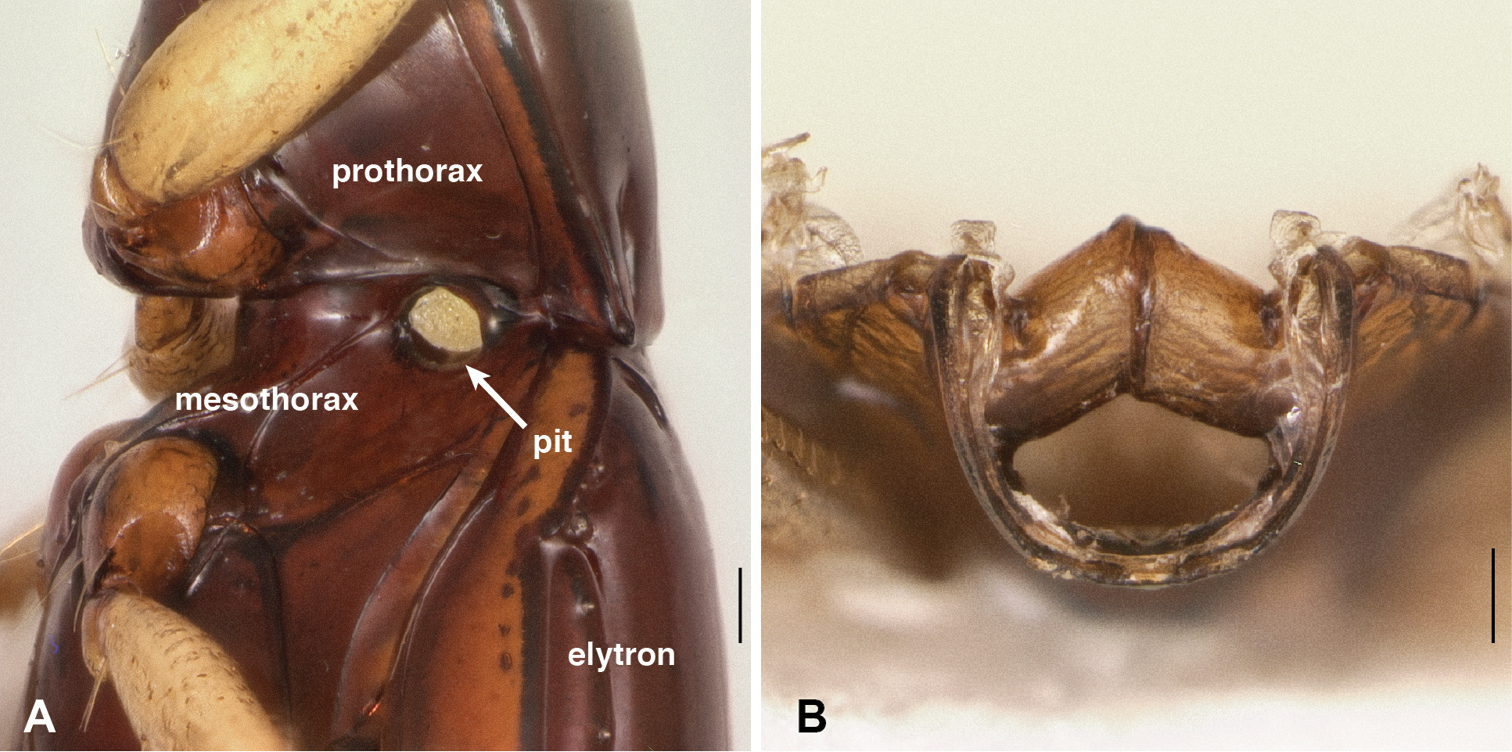

Mesothoracic pits. The most striking derived feature observed was presence in all Nothonepha species of a pit in each lateral wall of the mesothorax. This mesepisternal pit (Fig. 9A) appears empty in many specimens killed in ethyl acetate, but in most specimens preserved in ethanol, a waxy substance is visible within it (Fig. 9A). When extracted and placed in glycerin on a microscope slide, this substance appears slightly yellowish-gray and contains no obvious substructure or particles (including no evident bacteria or fungal spores) when examined at 400× with transmitted, brightfield light (n=2, from Bembidion tetrapholeon). In contrast, all other members of Bembidion examined to date lack such a pit (e.g., Fig. 9B).

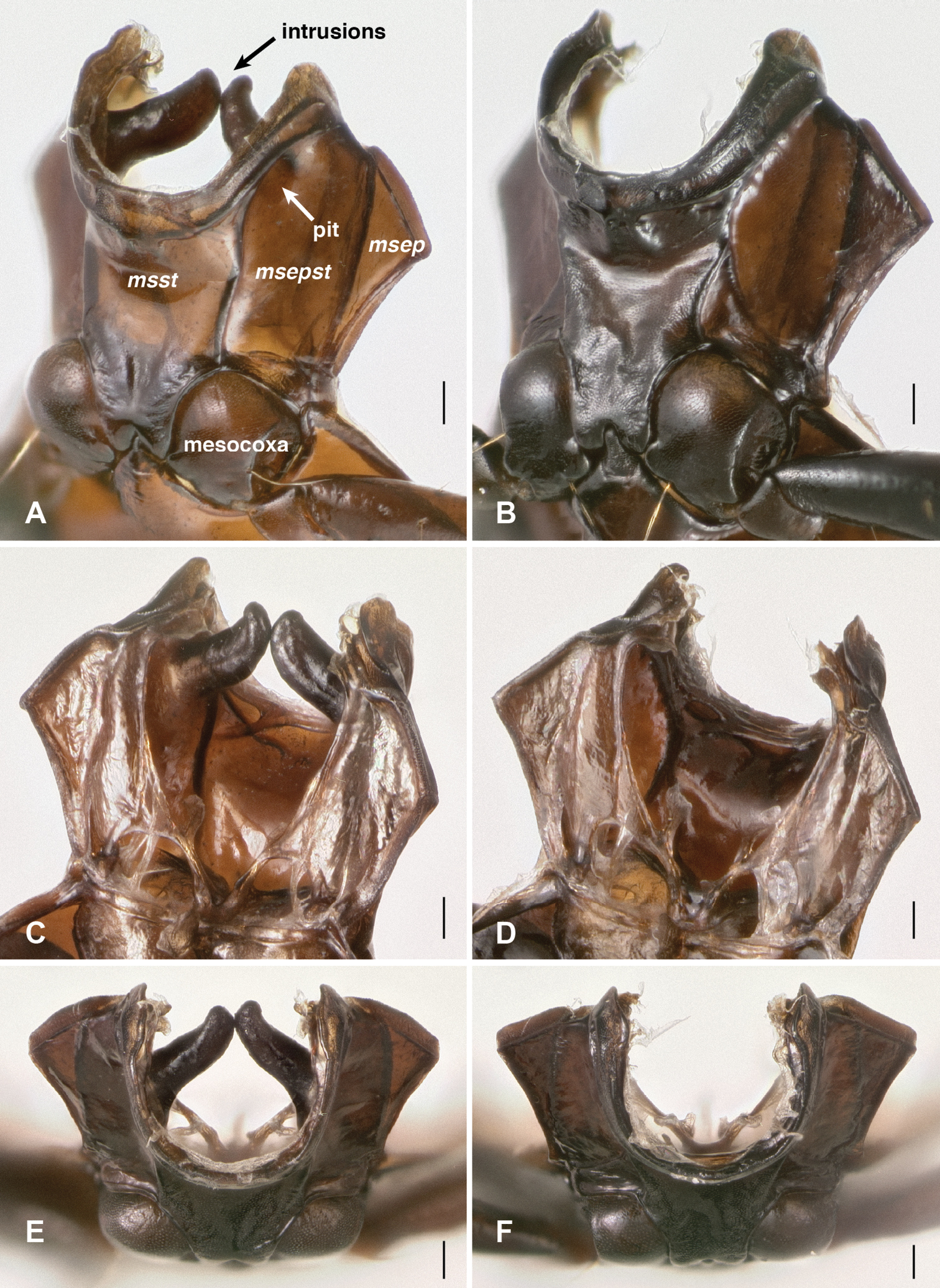

Left lateral region of the prothorax and mesothorax; top of each photograph is anterior. msst: mesosternum; msepst: mesepisternum; msep: mesepimeron (note that the boundaries between these sclerites are not evident externally in A. A Bembidion (Nothonepha) tetrapholeon, DRM voucher V100810 B Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) zanettii, DRM voucher V100811. Scale bar 0.1 mm.

In Bembidion tetrapholeon these paired structures, one on either side, internally manifest as large intrusions which touch in the center of the body cavity (Figs 10A, C, E). Typical Bembidion have no such structures internally (Figs 10B, D, F). There is variation within Nothonepha in the size of the intrusions, with Bembidion engelhardti having relatively small intrusions (and thus relatively shallow pits) (Fig. 11).

Mesothorax, dorsal surface and soft tissue removed. msst: mesosternum; msepst: mesepisternum; msep: mesepimeron. Scale bar 0.1 mm. (A, C and E) Bembidion (Nothonepha) tetrapholeon, DRM voucher V100766 B, D, and F Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) zanettii, DRM voucher V100767 A, B oblique ventral view; view from lower left side, slightly in front of mesothorax. C, D oblique dorsal view; view from upper right side, slightly behind the mesothorax. E, F anterior view.

Mesothorax, dorsal surface and soft tissue removed, of Bembidion (Nothonepha) engelhardti rayoda Toledano. Oblique dorsal view; view from upper right side, slightly behind the mesothorax. Scale bar 0.1 mm.

Examination of musculature in Bembidion tetrapholeon (n=4) and Bembidion tucumanum (n=1) revealed no muscles attached to the internal intrusions, although the course of some muscles appeared to be bent by the necessity to wrap around the structures. There were no evident large glands associated with the intrusions, although there were small patches of tissue on their internal surfaces.

Two other groups of carabids reported to have mesepisternal pits were also examined, members of subgenus Tachylopha of the genus Elaphropus (

Mesothoracic structures of Elaphropus (Tachylopha) leleupi Basilewsky. A Left lateral region of the prothorax and mesothorax B Anterior view of mesothorax, dorsal surface and soft tissue removed. Scale bars 0.1 mm.

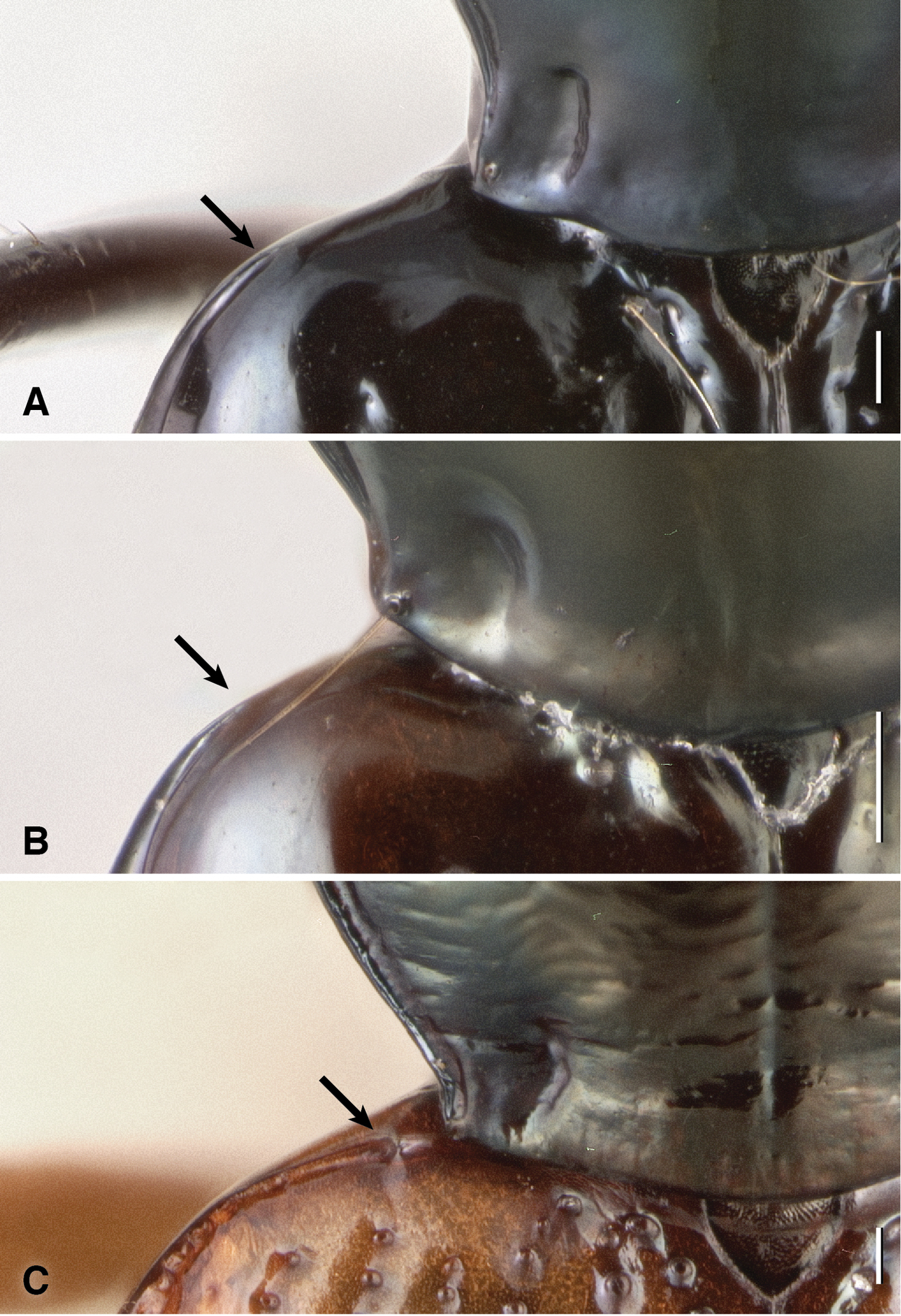

Abdominal pits. In additional to mesepisternal pits, Bembidion tetrapholeon has a prominent pit on each side of the abdomen, ventrally, between abdominal segments II and III (Fig. 13A). In ethanol-preserved specimens, this pit is filled with a waxy substance similar to that in the mesepisternal pits. Almost all other species of subgenus Nothonepha have similar pits (e.g., Bembidion (Nothonepha) sp. nr. lonae, Fig. 13C); they are lacking only in Bembidion (Nothonepha) lonae (Fig. 13D), the sister to Bembidion sp. nr. lonae.

Ventral surface of anterior end of abdomen and posterior region of metathorax. The second and third abdominal segments are marked by II and III. A Bembidion tetrapholeon, DRM voucher V100773. B Bembidium mandibulare, DRM voucher V100772 C Bembidion sp. nr. lonae, DRM voucher V100771 D Bembidion lonae, DRM voucher V100770. Scale bar 0.1 mm.

Internally these abdominal pits are evident as knob-shaped intrusions (Fig. 14A, C). Consistent with the lack of externally visible pits, Bembidion lonae lacks these intrusions, and has instead only a ridge between the abdominal segments (Fig. 14D), as is typical in Bembidion.

Inner surface of the anterior portion of the abdomen, soft tissue removed. The abdomen is slightly tilted to the left. sp: sclerotized patch on membrane that bounds the front of the abdomen on the ventral side. All species shown are members of the Bembidion Series; A–F are members of the Antiperyphanes Complex; A, C and D are members of the subgenus Nothonepha A Bembidion tetrapholeon, DRM voucher V100766 B Bembidium mandibulare, DRM voucher V100805 C Bembidion sp. nr. lonae, DRM voucher V100803 D Bembidion lonae, DRM voucher V100802 E Bembidium philippii, DRM voucher V100804 F Bembidion chimborazonum, DRM voucher V100809 G Bembidion charile Bates, DRM voucher DNA1171 H Bembidion quadrimaculatum oppositum Say, DRM voucher V100807. Scale bar 0.1 mm.

Outside of Nothonepha I have seen no species of Bembidion with as prominent abdominal pits, and most species lack them entirely. Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) mandibulare, for example, lacks abdominal pits and has only a slight linear depression in that region (Fig. 13B), and internally a simple ridge is evident (Fig. 14B). There is much variation between members of the Antiperyphanes Complex in this feature, however, with some species having an evident pit/internal intrusion (e.g., Bembidion (Antiperyphus) philippii, Fig. 14E, and Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) zanettii), and others (e.g., Bembidion (Ecuadion) chimborazonum, Fig. 14F) having a low, wide hump internally. Outside of the Antiperyphanes Complex all species examined either have a sinuate (Fig. 14G) or straight (Fig. 14H) ridge internally in this region.

Whatever internal structure is present between abdominal segments II and III, whether a ridge, or low mound, or knob-like intrusion, in the species examined this structure serves (at least in part) as an apodeme. In Bembidion tetrapholeon (n=5), for example, a muscle bundle is attached to the apex of the internal intrusion, and extends forward to the small sclerotized patch (sp in Fig. 14C) in the membrane that serves as the front boundary above the ventral margin of the abdomen. Another muscle bundle extends from this sclerotized patch forward and laterally to the lateral wall of the body, where it attaches to an external rod-like sclerite that is connected to the posterior lateral corner of the metanotum; this rod-like sclerite extends posterior laterally from that point to near the metepimeron. I have examined Bembidion (Ecuadion) chimborazonum (n=1) and it has a similar muscle attached to the low mound in the same region; Bembidion (Bracteon) foveum Motschulsky (n=1), Bembidion (Ocydromus Complex) nebraskense (n=2), and the bembidiine Lionepha casta (n=2) all have a similar muscle connecting the intersegmental ridge at the equivalent region to the small sclerotized patch.

Monophyly of Nothonepha. DNA data strongly support Nothonepha as a clade. Four genes (CAD, wg, 28S, 18S) independently have bootstrap support for the clade (Table 3), and the concatenated seven-gene analysis has MLB=100 and PB=100. Combined with the striking synapomorphy of mesothoracic pits, evidence for this clade becomes convincing. As

The unexpectedness of Nothonepha. The relationship between species here grouped into subgenus Nothonepha was so unexpected when first discovered from sequences of 28S that it was dismissed, and considered to be the result of DNA contamination or mislabeled extractions. This small clade, of only ten known species, includes some of the largest Bembidion in South America (Bembidion germainianum, up to 6.4 mm in length, Fig. 5C), and some of the smallest (Bembidion lonae, down to 2.4 mm in length, Fig. 5D). They range in habitat from cobbles shores of small, cold, clear rivers (Fig. 6D) to mixed shores of large rivers (Fig. 6A), and sand shores of desert rivers (Fig. 6C) to warm, exposed salt flats (Fig. 6B). In the field, beetles in this group give the appearance of rather different groups of carabids. In my first field encounter with live Bembidion lonae, I mistook them for tachyines of the genus Elaphropus Motschulsky; Bembidion germainianum is reminiscent of the Nearctic Bembidion perspicuum Casey, a member of the Ocydromus Series of Bembidion; Bembidion eburneonigrum looks very much like a small member of the subgenus Notaphus as it scurries on the sandy shores of rivers.

There are many examples of clades throughout the tree of life that contain species of diverse forms living in diverse habitats. Why then is Nothonepha unexpected? The current classification, to the extent that it might be a predictor of relationships, would suggest that these taxa are not related. Bembidion lonae is the only described species of those sampled that was placed in Nothonepha; the very similar but undescribed Bembidion sp. nr. lonae would have been placed there as well. The other described species (Bembidion germainianum, Bembidion engelhardti, Bembidion tucumanum, Bembidion eburneonigrum, and Bembidion tucumanum) had all been classified in subgenus Antiperyphus, along with Bembidium philippii. When I first discovered Bembidion tetrapholeon, I thought it represented a separate lineage requiring a new subgeneric name, as it is very different in form from any other South American Bembidion. This apparently added a third element to the diverse group. However, the current classification, constructed with limited data and without phylogenetic analyses, may not be the best predictor of phylogenetic relationships.

Nonetheless, Nothonepha is a morphologically heterogeneous group (Fig. 6). I have been studying Bembidion systematics for over three decades, and whatever predictive map my brain has developed from all the data accumulated over the years contained no hint that the species shown in Fig. 6 formed a clade.

However, it may not be the diversity of form within Nothonepha that is unusual, but rather the diversity given the lack of intermediate forms and small size of the group. Other clades in the South American fauna are also diverse in form and size (e.g., Ecuadion, Fig. 3), but they have many more species, some of which are intermediate between the more distinct forms. The lack of intermediate forms in Nothonepha may be a result of low speciation rates with high rates of morphological evolution, or it might be a result of extinction of intermediate forms; it is unlikely to be a lack of sampling, as enough collecting has been done in South America to suggest that there are not a large number of undescribed species of Nothonepha. A full investigation of patterns of morphological and molecular rates, times of divergence, and speciation and extinction rates relative to other clades is beyond the scope of this paper, but would be a worthwhile topic for future studies.

Function of mesepisternal pits. Exoskeletal invaginations are widespread in beetles (

The functions of mesepisternal pits in the two carabid groups in which they were previously described is not known, but functions have been hypothesized.

The similarities between the wax-filled mesepisternal pits observed in the bembidiine Bembidion (Nothonepha), the tachyines Elaphropus (Tachylopha) and Elaphropus (Sphaerotachys), and the oodine Oodinus are striking (e.g., Figs 9A and 12A in this paper, and Fig. 145 in

Correlates in way of life might provide some hints about function. Members of the three carabid groups are all presumably generalist predators, as is typical in Carabidae (

It appears unlikely that mesepisternal pits are used as ant handles in Bembidion (Nothonepha) and Oodinus, and probably not in Elaphropus (Tachylopha).

There is also evidence against the mesepisternal pits functioning as apodemes. As noted above, Nothonepha and Tachylopha do not have muscles attached to the internal walls of the mesepisternal pits.

It is possible that the function is as a reservoir for the wax, although where the wax is produced is not evident.

Whatever the source of the wax, its function (if it has one) is unclear. It seems unlikely that it would be for retaining fungal spores (

Function of abdominal pits. In contrast to the mesepisternal pits, the abdominal pits in Bembidion (Nothonepha) evidently serve (in part) as apodemes, that is, as attachment points for muscles. However, the function of those muscles is unclear; in general the nature and function of muscles at the junction of the metathorax and abdomen in beetles is poorly known (Rolf Beutel, pers. comm. 2014). Even if the abdominal pits serve as apodemes, they may serve additional functions as well, perhaps related to the presence of wax that appears similar to that found in the mesepisternal pits.

Three clades of Bembidion comprise the South American fauna: subgenus Notaphus Dejean (32 species (

Members of the Antiperyphanes Complex are diverse in form (Figs 1–3, 5). There are no recognized derived morphological characteristics of the group, although the clade is moderately well supported by the concatenated DNA sequence data (Fig. 8, Table 3). Within the South American fauna, most species can be recognized by the lack of an N sclerite in the internal sac of the male genitalia (

The Antiperyphanes Complex, as here classified, consists of at least five subgenera: Antiperyphanes, Chilioperyphus, Antiperyphus, Notholopha, Ecuadion, and Nothonepha. Each of these subgenera is briefly discussed below, with notes about their composition. Two other poorly known subgenera, Pseudotrepanes Jeannel and Notoperyphus Bonniard de Saludo, are likely members of this complex, but specimens will need to be examined to confirm their membership.

This group contains at least 19 described species (

Included here are some species previously placed in subgenus Antiperyphus by

Antiperyphanes has two distinct clades, each very well supported: the Bembidion caoduroi group (clade j in Fig. 8; Fig. 1D), consisting (among the sampled species) of three large species from the northern Andes (Fig. 1D); (2) the remaining Antiperypanes (clade k in Fig. 8; Figs 1A–C, E). Each is supported by MLB=100 and PB=100 in the multi-gene analyses, and individually by support from five to seven genes (Table 3). As a whole, however, the monophyly of Antiperyphanes is only weakly supported by the combined analysis and analyses of four genes (Table 3).

Members of this subgenus are found at the edges of bodies of water. For example, Bembidion rufoplagiatum and Bembidion zanettii are common on gravel and cobble river shores, Bembidion ringueleti is found on gravel and sand shores of smaller creeks, and Bembidium mandibulare on the sand beaches of the Pacific Ocean in Chile and sand beaches of rivers in Argentina.

This subgenus contains two described species (

As noted by

In addition, Bembidion peterseni

B. philippii is common on sand shores of rivers in the provinces of Neuquén and Chubut in Argentina; it also occurs in Chile.

Notholopha consists of 11 described species (

Jeannel considered Pacmophena and Notholopha to be two subgenera within the genus Notholopha. As the characters that Jeannel used to distinguish the two are minor characters such as surface texture and antennal length, and as it appears that Pacmophena is paraphyletic with respect to the Notholopha (s. str.) (Fig. 7), I consider them synonymous, with Notholopha as the valid name.

Ecuadion is the largest subgenus in the Antiperyphanes Complex, with over 50 described species (

Ecuadion falls into two distinct clades among the sampled species: (1) the Bembidion chimborazonum group (clade m in Fig. 8), consisting mostly of larger, long-legged species (Figs 3A, B); (2) remaining Ecuadion (clade n in Fig. 8), consisting of mostly smaller species with shorter appendages (Figs 3C–F). The Bembidion chimborazonum group is supported by all genes examined (Table 3); support for the complementary clade is not quite as strong, with the clearest evidence coming from ribosomal genes (Table 3).

Unlike most Bembidion, this subgenus has radiated in habitats away from water. Some occur in leaf litter in cloud forests (e.g., Bembidion andersoni, Bembidion georgeballi, Bembidion onorei, Bembidion sp. “Papallacta”; Fig. 4D), in habitats that would typically be occupied by the genus Trechus Clairville in North America. A number of species are found in open, high-elevation grasslands (e.g., Bembidion chimborazonum, Bembidion guamani, Bembidion humboldti; Fig. 4C). Some species occur on the upper banks of creek shores (e.g., Bembidion sanctaemarthae, Bembidion ricei); others are found on clay or silt cliffs (e.g., Bembidion agonoides, Bembidion walterrossii).

As here defined, the subgenus Nothonepha includes all species of the Antiperyphanes Complex possessing mesepisternal pits. Seven described species belong to Nothonepha:

Bembidion lonae Jensen-Haarup, 1910 (Fig. 5D)

Bembidion pallideguttula Jensen-Haarup, 1910

Bembidion eburneonigrum Germain, 1906 (Fig. 5E)

Bembidion engelhardti Jensen-Haarup, 1910

Bembidion engelhardti engelhardti Jensen-Haarup, 1910 (Fig. 5G)

Bembidion engelhardti rayoda Toledano, 2008

Bembidion tucumanum (Jeannel, 1962) (Fig. 5F)

Bembidion germainianum Toledano, 2002 (Fig. 5C)

Bembidion tetrapholeon Maddison, sp. n. (Figs 5A, B)

Four of these species (Bembidion germainianum, Bembidion tucumanum, Bembidion engelhardti, and Bembidion eburneonigrum) were formerly placed in subgenus Antiperyphus. In addition, there are at least three undescribed species (including Bembidion sp. nr. lonae, sequenced here). The species figured by

http://zoobank.org/90188564-6B1E-4F0E-B411-5AD99047F716

Figs 5A, B, 9A, 15, 16, 17A, 18male (IADIZA), with 3 labels: “Argentina: Neuquén: Arroyo / Queñi at Lago Queñi, 830m, / 40.1575°S, 71.721°W, / 10-11.ii.2007. DRM 07.035. / D.R. Maddison, S.A.Roig”, “David R. Maddison / DNA2356 / DNA Voucher” [printed on pale green paper], and “HOLOTYPE / Bembidion / tetrapholeon / David R. Maddison” [printed on red paper]. Genitalia in glycerine in small plastic vial beneath specimen; extracted DNA stored separately. GenBank accession numbers for DNA sequences of the holotype are KJ653049 (28S), KJ653145 (COI), KJ653112 (CAD), KJ653181 (Topo), KJ653215 (wg), and KJ653082 (ArgK).

Total of 244, in IADIZA, MACN, MNNC, OSAC, MNHN, BMNH, EMEC, CTVR, and CMNH, from “Argentina: Neuquén: Arroyo / Queñi at Lago Queñi, 830m, / 40.1575°S, 71.721°W, / 10–11.ii.2007. DRM 07.035. / D.R. Maddison, S.A.Roig” [135 exx.], Argentina: Neuquén: Rio Pichi / Traful nr Lago Traful, 810m, / 40.4867°S, 71.5958°W, / 12.ii.2007. DRM 07.039. / D.R. Maddison, S.A.Roig” [95 exx], “Argentina: Chubut: Rio / Azul at Lago Puelo, 200m / 42.0929°S, 71.6244°W / 13.ii.2007. DRM 07.044. / D.R. Maddison” [12 exx], “Argentina: Chubut: Rio / Azul at Lago Puelo, 200m / 42.0929°S, 71.6244°W, / 13.ii.2007. DRM 07.045. / S.A.Roig, D.R. Maddison” [1 exx].

CHILE: Reg. X, Chiloé: Rio Puntra at rt 5, 55m, 42.1661°S, 73.7256°W, 19.i.2006. DRM 06.075. D.R. Maddison [5 exx, OSAC, MNNC]. CHILE: Region X, Rio Pullinque at Puente Huanehue, 8 km NE Panguipulli. 16 Jan 2002, 39.6162°S, 72.2286°W, 1590 ft. W. D. Shepard [2 exx, OSAC].

The following specimens have been examined by Luca Toledano and confirmed to belong to this species (based upon photographs we have shared). CHILE: Reg. X, Los Lagos, P.N. Vicente Péres Rosales, Petrohué, Lago Todos los Santos, 190m, mouth Rio El Caulle, 41.0924°S, 72.3950°W. 5.i.2014. L. Toledano, R. Olivieri, J.P. Morales. [1 ex, CTVR]; CHILE: Region XI, Parque Nat. Rio Simpson, H. Franz [4 exx, NHMW]; CHILE: Reg. X, I. Chiloé, R. Punta, 31.i.1986. M. Spies. [1 ex, USNM].

Argentina: Neuquén: Arroyo Queñi at Lago Queñi, 830m, 40.1575°S, 71.7210°W. The habitat at the type locality is a cobble, gravel, and coarse sand river shore (Fig. 6D); the river is cold and has crystal-clear water. In the same habitat members of the genus Bembidarenas Erwin are abundant, as is Bembidion (Antiperyphanes) rufoplagiatum.

From the Greek “tetra”, meaning “four”, and “pholeon”, meaning “pit”, referring to the four prominent pits visible on the underside of adults.

A large, sleek, shiny Bembidion, with an unusual body form (Figs 5A, B) of narrow forebody and large elytra. With its shape, color, and smoothness it is one of the most distinctive Bembidion species in South America, and no other known species is likely to be confused with it; it is more reminiscent of some species in New Zealand, e.g., Bembidion (Zeplataphus) dehiscens Broun (

Length (4.7–5.7 mm, with most specimens above 5.0 mm). Color piceous (Fig. 5A), with legs and antennae in some specimens slightly paler, and with a few specimens having a large orange spot just in front of the elytral apices (Fig. 5B).

Head with shallow and parallel frontal furrows.

Pronotum narrow, cordate, with hind angles flaring outward (Fig. 15). Very smooth, without punctures, and with a linear basolateral foveae; without distinct carina at hind angle. Lateral bead of pronotum not complete, not reaching front angle of prothorax and only in some specimens reaching the hind angle. One midlateral and one basolateral seta on each side.

Pronotum of Bembidion tetrapholeon, DRM voucher V100781. Scale bar 0.1 mm.

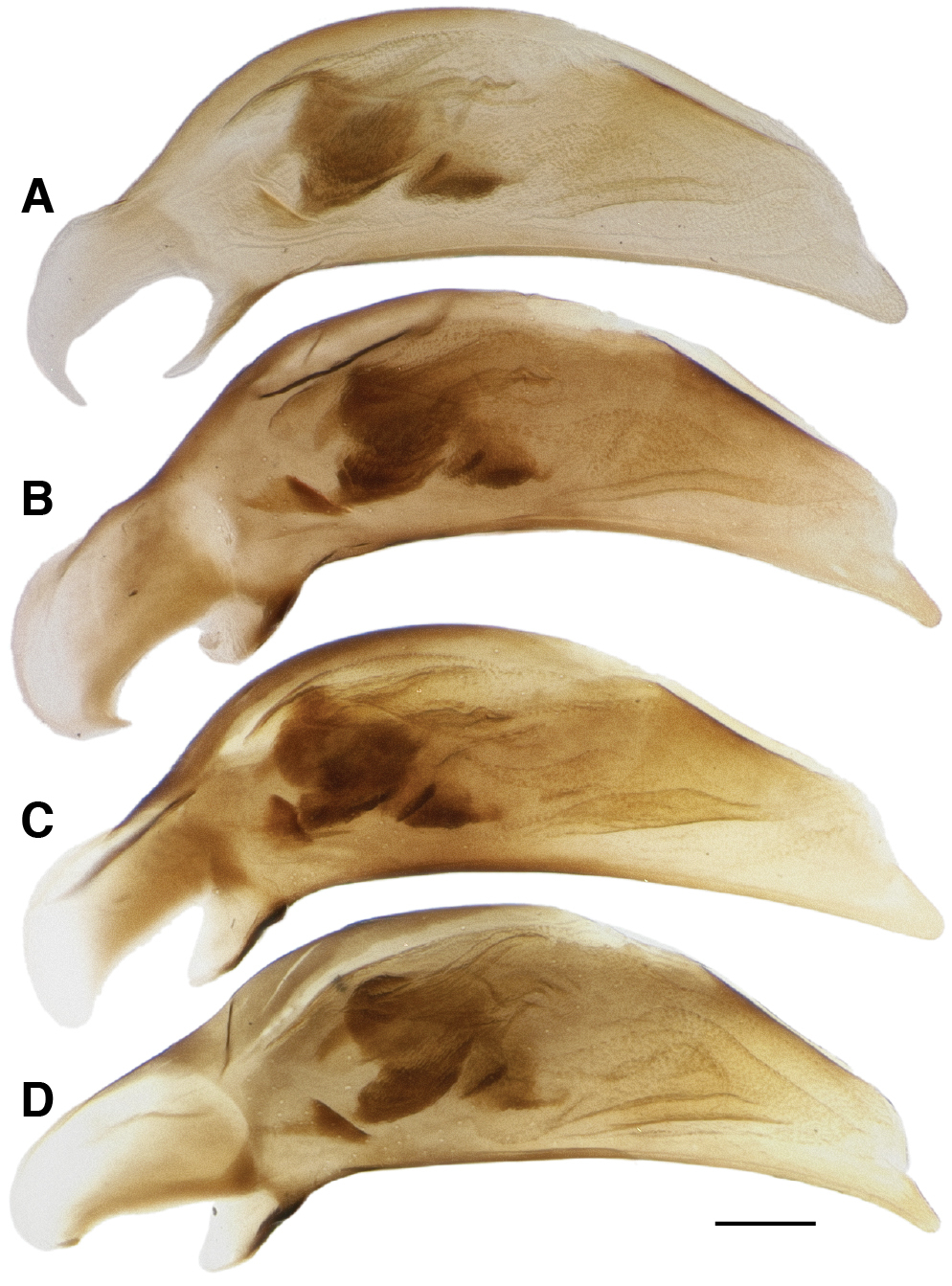

Each elytron with two discal setae (ed3 and ed5); ed3 in third stria. Elytral striae with prominent punctures in their basal half, but with striae 2–7 absent in about the hind 40% or more of the elytra, such that the posterior discal seta, ed5, is in a region without striae. Striae 7 absent in many specimens. In many specimens the striae are effaced anteriorly, especially striae 2 and 3. Lateral bead of elytron effaced anteriorly, not extended onto shoulder (Fig. 16A), similar to that of Bembidion (Nothonepha) lonae (Fig. 16B), but unlike most other Bembidion (e.g., Bembidion (Nothonepha) germainianum, Fig. 16C).

Humeral region of left elytron and posterior corner of pronotum of three Bembidion (Nothonepha) species. A Bembidion tetrapholeon, DRM voucher V100781 B Bembidion lonae, DRM voucher V100786 C Bembidion germainianum, DRM voucher V100782. Arrows show the anterior end of the lateral elytral groove and bead. Scale bar 0.1 mm.

Mesothorax with prominent pits in the mesepisternum (Fig. 9A), which appear internally as large intrusions that touch in the middle (Figs 10A, C, E). Smaller pits are present ventrally at the junction of abdominal segments II and III (Fig. 13A), which are evident internally as knob-like intrusions (Fig. 14A).

Hind wings full.

Microsculpture absent from entire dorsal surface of the body except for the cervical region of the head, labrum, and faintly on the clypeus; the beetles are thus brilliantly shiny. Microsculpture absent from most of the ventral surface as well, with the most notable microsculpture being on the undersurface of the head.

Aedeagus with nearly straight ventral margin, tip of variable width (Fig. 17). Prominent brush sclerite, and with flagellum not clearly evident from the left side. There is no evident correlation between aedeagal structure and presence or absence of orange spots on the elytra (compare Figs 17A, B to Figs 17C, D).

Male aedeagus of Bembidion tetrapholeon. A Black form, Chile: Region X, Rio Pullinque at Puente Huanehue, 8 km NE Panguipulli, DRM voucher DNA1752 B Black form, Chile: Reg. X, Chiloé: Rio Puntra at route 5, DRM voucher DNA2236 C Orange-spotted form, Argentina: Neuquén: Rio Pichi Traful nr Lago Traful, DRM voucher DNA2564 D Orange-spotted form, Argentina: Neuquén: Rio Pichi Traful nr Lago Traful, DRM voucher DNA2555. Scale bar 0.1 mm.

The most noted variation is in color of the elytra. Of the 257 specimens examined (including the six specimens identified by Luca Toledano), 245 have uniformly piceous elytra (Fig. 5A); the remaining 12 have a large, diffuse orange spot occupying most of the posterior third of the elytra (Fig. 5B). Ten of these orange-spotted specimens are from the three localities in Argentina, with at least one orange-spotted specimen from each locality, and two of the orange-spotted specimens are from Chile. In most of orange-spotted specimens, the posterior discal seta (ed5) is in the orange region, but immediately around the seta is a small dark spot. No other aspect of morphological or molecular variation was observed to be correlated with presence or absence of the orange spot.

As noted above under Results, there was minor variation present in COI and the wingless gene, and no variation in the other genes studied.

At all four localities where habitat data were recorded, Bembidion tetrapholeon specimens were found on cobble, gravel, and coarse sand shores of clear, fast-flowing rivers (Fig. 6D), from 55 m elevation (Rio Puntra, Isla Grande de Chiloé, Chile) to 830 m elevation (Arroyo Queñi, Neuquén, Argentina). These shorelines lack vascular plants. The beetles occur close to the water, most within 1 m. Specimens have been found in January and February.

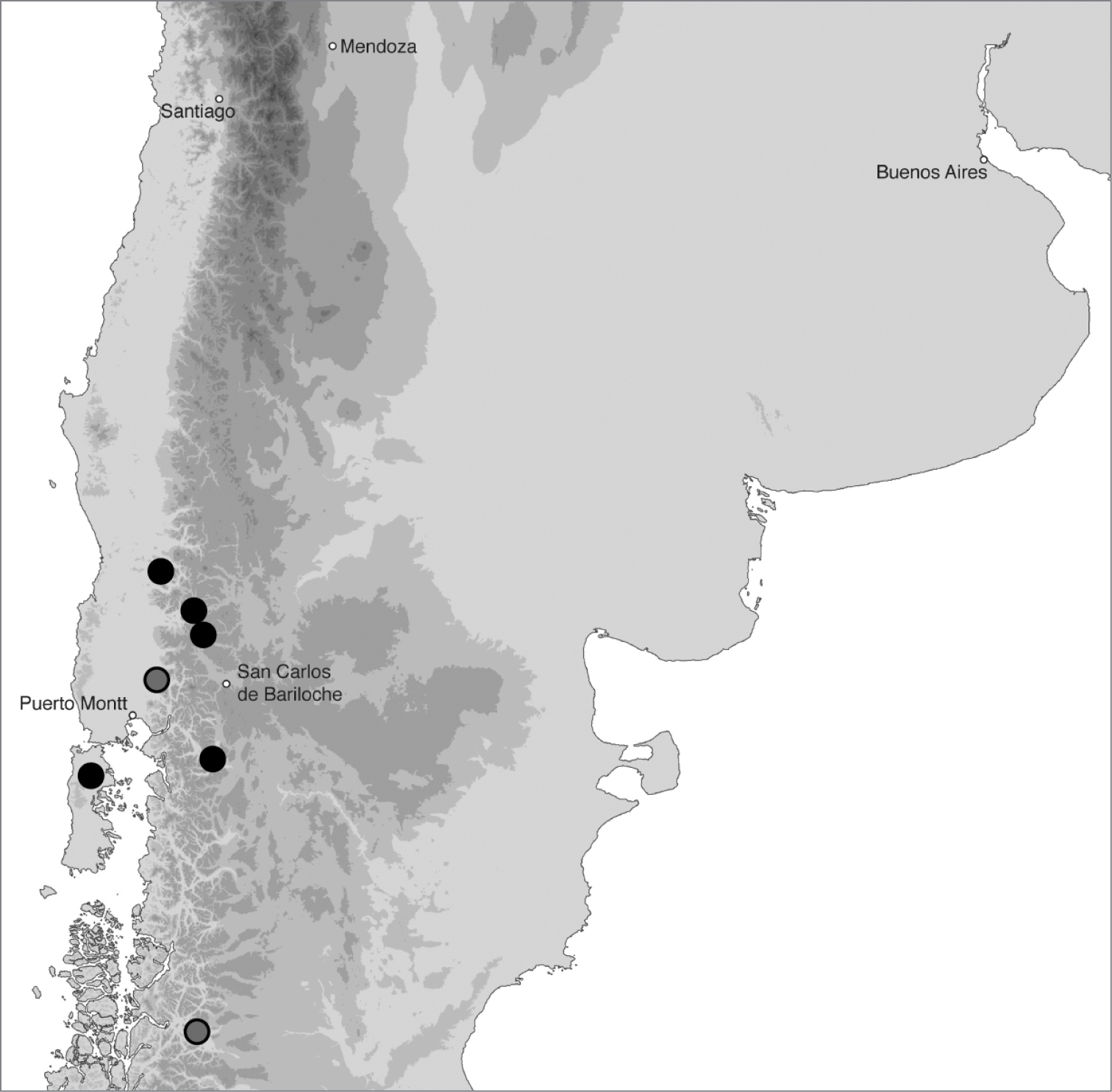

In southern Argentina and Chile (Fig. 18). In Argentina this species has been found in Neuquén and Chubut, and in Chile from Regions X and XI.

Geographic distribution of Bembidion tetrapholeon. Circles filled in black are based upon specimens I have examined and that have been sequenced; circles filled in gray are based upon specimens identified by Luca Toledano. Five cities are included as landmarks.

Bembidion tetrapholeon is a member of subgenus Nothonepha, as strongly supported by DNA sequences (Table 3) and the presence of shared, derived mesepisternal pits. Bembidion tetrapholeon appears to be the sister of remaining Bembidion (Nothonepha) (Figs 7, 8). Four genes support this placement (CAD, wg, ArgK, and 18S; Table 3), although the support is weak or moderate in single-gene analyses.

“when the same organ appears in several members of the same class, especially if in members having very different habits of life, we may attribute its presence to inheritance from a common ancestor.” (

In groups such as beetles, in which a preponderance of lineages split without later reticulation, the evolutionary tree at the core of life’s history yields hierarchical patterns in the distributions of characteristics. Any particular lineage in the tree, if separated long enough or with a high enough rate of evolution, will leave in the bodies of its descendants marks of its existence. The echoes from that deep historical well can reverberate down through later lineages in the form of signals scattered throughout the genomes. The repeated patterns of these branch markers both in the DNA and on the bodies of organisms are among the most compelling signs of the existence of the tree of life, and provide to us evidence about its shape. On occasion the clades thereby revealed are so unexpected that it is only with multiple independent markers, all showing the same pattern, that we can confidently accept the existence of the clade. Nothonepha is such a clade.

Many of us who study the diversity of life, and see the hierarchical patterns of organismal traits, are steeped in evidence of the existence of a genetic tree of life, so much so that we perhaps take it for granted (I often do). I think about the evidence about the tree’s shape, but much less so evidence about its existence. In encountering the first evidence of Nothonepha, my belief in the tree-like structure of beetle genetic history was challenged, as the data made little sense in that light. As newly sequenced genes added to the evidence, my acceptance of the clade increased. The struggle was fully resolved when the mesothoracic pits came to light; this harmonizing of the morphological data with the molecular not only instilled a firm belief in this clade, but also a simple confirmation of the tree itself.

I am most grateful to Sergio Roig-Juñent, who arranged the collecting expedition that yielded most known specimens of Bembidion tetrapholeon, and most of the other Nothonepha studied; he was also a very welcome companion on the trip.

I am very thankful to all those who helped with a collecting expedition to Ecuador during which most sequenced members of subgenus Ecuadion were collected. Mauricio Vega arranged many details of the trip, including relevant collecting and export permits; Wayne Maddison, Marco Reyes, and Mauricio Vega accompanied the author into the field and helped collect the specimens. I am also grateful to Reserva Yanacocha, Pichincha, Ecuador, for permission to collect on their lands. The Ecuadorian Ministry of the Environment and the Museum of Zoology of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Ecuador assisted with permits.

I would also like to thank Elizabeth Arias and Kipling Will for organizing and providing excellent logistical support, including permit acquisition, for field work in Chile. I am also grateful for their companionship during my first experience with South American Bembidion.

Some key specimens were provided by others, and I am thankful for their contributions; without a network of collectors, a work such as this would not be possible. In particular, I would like to thank William D. Shepard (for the Rio Pullinque specimen of Bembidion tetrapholeon), Wendy Moore (Bembidion tucumanum), Karl M. Kjer (for South African Tachylopha), Geoff B. Monteith (for Australian Tachylopha), Caroline S. Chaboo (for South African Sphaerotachys), and James M. Pflug (for Oodinus from Texas).

I am also grateful to Luca Toledano, both for his review of the manuscript, and for the information he provided about specimens of Bembidion tetrapholeon he has examined from Chile. My thanks to Wayne Maddison and an anonymous reviewer for their comments on the manuscript. Thanks as well to myrmecologists Alex Wild and Philip Ward for discussing the ants that might live in the same habitats as Nothonepha, Tachylopha, and Oodinus.

This project was made possible by funds provided by the University of Arizona, the Harold E. and Leona M. Rice Endowment Fund at Oregon State University, and National Sciences Foundation grant EF-0531754. National Sciences Foundation DEB-0445413, to Elizabeth Arias and Kipling Will, provided funds that helped support field work in Chile. The expedition to South Africa that yielded the Elaphropus (Sphaerotachys) I studied was supported by a Hellman Postdoctoral Fellowship (to C.S. Chaboo).

Locality data for newly sequenced specimens

Locality data for Bembidion specimens newly sequenced for this study. Under “#” the D.R. Maddison DNA voucher number is listed.

| # | Locality | |

|---|---|---|

| Bembidion agonoides | 2675 | ECUADOR: Napo: Vinillos, 4.1 km S Cosanga, 2090m, 0.6024°S, 77.8509°W |

| Bembidion andersoni | 2651 | ECUADOR: Pichincha: Reserva Yanacocha, start Andean Snipe Trail, 3540m, 0.1152°S, 78.5837°W |

| Bembidion chimborazonum | 2659 | ECUADOR: Pichincha: Paso de la Virgen, 4070m, 0.3331°S, 78.2025°W |

| Bembidion cotopaxi | 2658 | ECUADOR: Pichincha: Quebrada Lozada, on road to Res. Yanacocha, 3460m, 0.1105°S, 78.5642°W |

| Bembidion eburneonigrum | 2204 | CHILE: Reg. IX: Rio Allipén at route 119, 132m, 39.0164°S, 72.5045°W |

| Bembidion engelhardti | 2334 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Rio Salado at route 40, 725m, 38.2143°S, 70.0931°W |

| Bembidion georgeballi | 2661 | ECUADOR: Pichincha: Quebrada Lozada, on road to Res. Yanacocha, 3455m, 0.1105°S, 78.5642°W |

| Bembidion germainianum | 2336 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Rio Salado at route 40, 725m, 38.2143°S, 70.0931°W |

| Bembidion guamani | 2660 | ECUADOR: Pichincha: Paso de la Virgen, 4070m, 0.3331°S, 78.2025°W |

| Bembidion humboldti | 2673 | ECUADOR: Pichincha: Paso de la Virgen, 4070m, 0.3331°S, 78.2025°W |

| Bembidion jimburae | 2674 | ECUADOR: Napo: Rio Guango, 2730m, 0.3758°S, 78.0748°W, 26.x.2010 |

| Bembidion neodelamarei | 2342 | ARGENTINA: Mendoza: Uspallata, 1880m, 32.5908°S, 69.3513°W, 25.ii.2007 |

| Bembidion onorei | 2678 | ECUADOR: Pichincha: Quebrada Lozada, on road to Res. Yanacocha, 3455m, 0.1105°S, 78.5642°W |

| Bembidion paulinae paulinae | 2783 | ECUADOR: Pichincha: Quebrada Lozada, on road to Res. Yanacocha, 3455m, 0.1105°S, 78.5642°W |

| Bembidium philippii | 2327 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Rio Collón Curá ca 13 km S La Rinconada, 625m, 40.1015°S, 70.7545°W |

| Bembidion ricei | 2653 | ECUADOR: Napo: Rio Chalpi Grande, 2800m, 0.3645°S, 78.0852°W |

| Bembidion sanctaemarthae | 2652 | ECUADOR: Napo: Rio Chalpi Grande, 2780m, 0.3657°S, 78.0848°W |

| Bembidion sp. nr. caoduroi | 2677 | ECUADOR: Napo: Rio Cosanga at mouth of Rio Angenaro, 2185m, 0.6407°S, 77.9083°W |

| Bembidion stricticolle | 2240 | CHILE: Reg. IX: ca. 28 km E Melipeuco, 1262m, 38.83°S, 71.4038°W |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 1752 | CHILE: Region X, Rio Pullinque at Puente Huanehue, 8 km NE Panguipulli. 39°36’58’’S, 72°13’43’’W, 1590 ft. |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 2236 | CHILE: Reg. X, Chiloé: Rio Puntra at rt 5, 55m, 42.1661°S, 73.7256°W |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 2356 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Arroyo Queñi at Lago Queñi, 830m, 40.1575°S, 71.7210°W |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 2357 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Arroyo Queñi at Lago Queñi, 830m, 40.1575°S, 71.7210°W |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 2555 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Rip Pichi Traful nr Lago Traful, 810m, 40.4867°S, 71.5958°W |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 2562 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Arroyo Queñi at Lago Queñi, 830m, 40.1575°S, 71.7210°W |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 2563 | ARGENTINA: Chubut: Rio Azul at Lago Puelo, 200m, 42.0929°S, 71.6244°W |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 2564 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Rip Pichi Traful nr Lago Traful, 810m, 40.4867°S, 71.5958°W |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 2565 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Rip Pichi Traful nr Lago Traful, 810m, 40.4867°S, 71.5958°W |

| Bembidion tetrapholeon | 2566 | ARGENTINA: Neuquén: Arroyo Queñi at Lago Queñi, 830m, 40.1575°S, 71.7210°W |

| Bembidion tucumanum | 1430 | ARGENTINA: Santa Cruz District, Dept. of Deseado, Cañadón Minerales. 25 km S. of Caleta Olivia. 46.7146°S, 67.367°W. 25m. |

| Bembidion walterrossii | 2650 | ECUADOR: Napo: Vinillos, 4.1 km S Cosanga, 2090m, 0.6024°S, 77.8509°W |

| Bembidion (Ecuadion) sp. “Mendoza” | 2701 | ARGENTINA: Mendoza: Reserva Villavicencio, 1540m, 32.5232°S, 68.9949°W |

| Bembidion (Ecuadion) sp. “Papallacta” | 2657 | ECUADOR: Napo: Papallacta, 3315m, 0.3703°S, 78.1481°W |

| Bembidion (Notholopha) sp. “Nahuelbuta” | 2239 | CHILE: Reg. IX: P.N. Nahuelbuta, 1090m, 37.8274°S, 73.0096°W |

NEXUS file containing DNA sequence matrices and maximum likelihood trees

Authors: David R. Maddison

Data type: NEXUS file with DNA data and trees

Explanation note: This is a NEXUS file containing the seven individual gene matrices as well as the two matrices of the concatenated genes. In addition, it contains the maximum likelihood trees for each matrix, and all of the bootstrap trees (2000 trees for each matrix). The file is formatted to be opened in Mesquite 2.75 or later.

Copyright notice: This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

NEXUS file containing DNA sequences for Bembidion tetrapholeon

Authors: David R. Maddison

Data type: NEXUS file with DNA data

Explanation note: This is a NEXUS file containing six matrices showing observed sequences for all of the specimens of Bembidion tetrapholeon sequenced. The file is formatted to be opened in Mesquite 2.75 or later.

Copyright notice: This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

Images of maximum likelihood trees

Authors: David R. Maddison

Data type: images of phylogenetic trees

Explanation note: This file shows the maximum likelihood trees for the concatenated, seven-gene matrices as well as each individual gene. Each figure is labeled to indicate the nature of the data analyzed for that tree.

Copyright notice: This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

Images of maximum likelihood bootstrap trees

Authors: David R. Maddison

Data type: images of phylogenetic trees

Explanation note: This file shows the maximum likelihood bootstrap trees for the concatenated, 7-gene matrices as well as each individual gene. Each figure is labeled to indicate the nature of the data analyzed for that tree. Numbers on each branch are the frequencies of that clade in the bootstrap replicates, expressed as a percentage.

Copyright notice: This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.