Citation: Esqueda-González MC, Ríos-Jara E, Galván-Villa CM, Rodríguez-Zaragoza FA (2014) Species composition, richness, and distribution of marine bivalve molluscs in Bahía de Mazatlán, México. ZooKeys 399: 43–69. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.399.6256

We describe the composition and distribution of bivalve molluscs from the sandy and rocky intertidal and the shallow subtidal environments of Bahía de Mazatlán, México. The bivalve fauna of the bay is represented by 89 living species in 28 families, including 37 new records and four range extensions: Lithophaga hastasia, Adula soleniformis, Mactrellona subalata, and Strigilla ervilia. The number of species increases from the upper (44) and lower intertidal (53) to the shallow subtidal (76), but only 11 (17%) have a wide distribution in the bay (i.e., found in all sampling sites and environments). The bivalve assemblages are composed of four main life forms: 27 epifaunal species, 26 infaunal, 16 semi-infaunal, and 20 endolithic. A taxonomic distinctness analysis identified the sampling sites and environments that contribute the most to the taxonomic diversity (species to suborder categories) of the bay. The present work increased significantly (31%) to 132 species previous inventories of bivalves of Bahía de Mazatlán. These species represent 34% of the bivalve diversity of the southern Golfo de California and approximately 15% of the Eastern Tropical Pacific region.

Mollusca, Bivalves, Taxonomic distinctness, Bahía de Mazatlán, Mexican Pacific

Studies on molluscs from Bahía de Mazatlán, located in the Mexican Pacific, have focused mainly on the conspicuous species of gastropods and bivalves from the rocky intertidal (

According to

Many studies on marine biodiversity have used species accumulation curves (i.e., sample-based rarefactions) to evaluate the sampling effort; this technique indicates when a sufficiently large percentage of species has been observed with a definite number of samples with respect to a theoretical expected total number of species of a given community (

Marine biodiversity has been evaluated with the taxonomic distinctness approach (

Bahía de Mazatlán is located in the southern portion of Golfo de California. The alternating warm and temperate seasons of this region create conditions that favor the development of a very diverse marine biota composed by species from both Golfo de California and the Mexican Tropical Pacific biogeographic subprovinces (

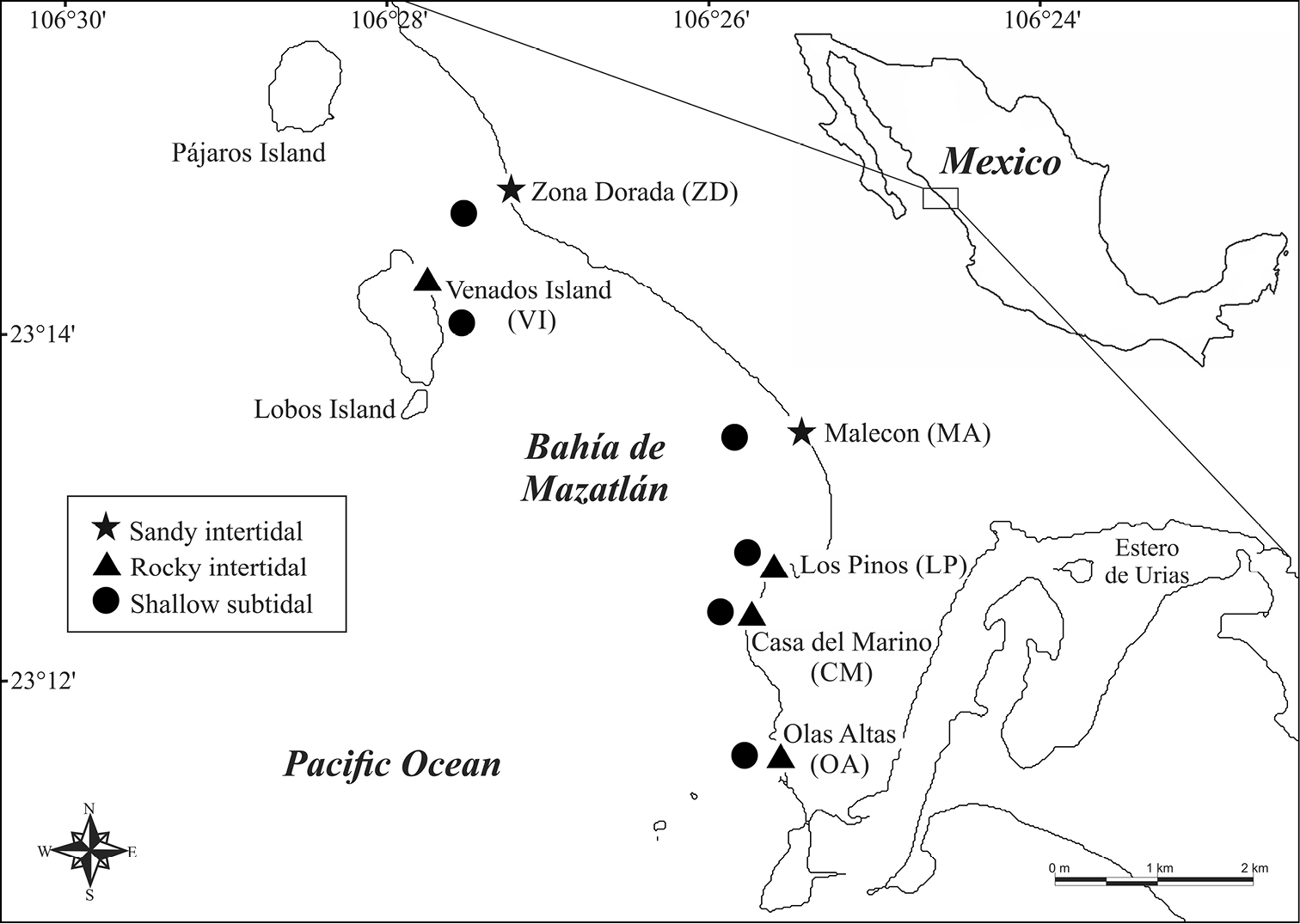

Study Area. Bahía de Mazatlán is located at the mouth of the Golfo de California (23°15'–23°11'N, 106°29'–106°25'W) (Figure 1). The bay has a total extent of approx. 3, 500 hectares and a coastline of 13.5 km. There are three major islands (Venados, Pájaros, and Lobos), located approximately 1.5 km off the coast. These islands are protected as ecological reserves for migratory birds and marine animals and plants, and part of the “Islands of the Golfo de California Protection Area” (

Study area and sampling sites at Bahía de Mazatlán, México.

The bay belongs to the Cortesian Eco-Region included in the Warm-Temperate Northeast Pacific Province (

Fieldwork. Six sampling sites protected or exposed to wave action conditions were established along Bahía de Mazatlán: four rocky beaches and two sandy beaches. Three environments were considered in each site: upper intertidal (UI), lower intertidal (LI), and shallow subtidal (SS) (3–10 m depth) adjacent to each beach. The intertidal zones were defined according to the natural zonation of benthic invertebrates (

Some of the general characteristics of these beaches are: 1) Olas Altas (OA), a partially-protected beach with a well-developed rocky area of approx. 150 m long and smaller areas of medium-to-coarse sand; 2) Los Pinos (LP), a protected rocky beach approx. 100 m long, with some areas of medium-to-coarse sand; 3) Casa del Marino (CM), a semi-protected to exposed rocky beach approx. 250 m long mixed with small sandy areas of fine-to-medium size grains; 4) Venados Island (VI), the east side of the island has an extensive protected sandy beach approx. 850 m long and 30–60 m wide with medium-to-coarse sand; towards the northern part of the beach there is a rocky beach approx. 200 m long with many tidal pools and boulders; 5) Malecon (MA), an exposed and very dynamic sandy beach approx. 400 m long of medium-to-coarse sand and pebbles. The beach runs along the urban sector of the city of Mazatlán and it is frequently visited by locals and tourists; and 6) Zona Dorada (ZD), a protected beach of medium-to-fine sand approx. 300 m long located in the tourist hub of the city just in front of hotels and extensively visited by tourists. The adjacent shallow subtidal environments of all these beaches include mixed substrates composed by coarse and fine sand, rocky reef areas, and many shell fragments. In Venados Island and Los Pinos small patches of live coral are also frequent.

Different sampling techniques (transect-quadrats, dredges, and direct searches) were applied during four expeditions in December 2008, and March, June, and August 2009. The transects (15 m long) were set parallel to the coastline, two in each environment (UI, LI, SS) of each beach. Two to four (x = 3) quadrats (0.5 m2) were placed equidistant along each transect and all bivalves found in each quadrat identified in situ or collected for taxonomic identification in the laboratory. In the shallow subtidal, sampling was performed during SCUBA diving. The total sampling effort was 126 quadrats (63 m2) in the rocky intertidal and 52 quadrats (26 m2) in the sandy intertidal. A total of 90 quadrats (45 m2) were sampled in the shallow subtidal environments of all beaches. Additionally, in order to increase the inventory of bivalves, the specimens found in the areas immediately adjacent to the quadrats were also identified in situ or collected during direct searches in the intertidal and shallow subtidal environments. Dredges (24) were carried out in the shallow subtidal zone (8–15 m depth) of the six beaches, using a naturalist´s dredge (mesh size = 2.5 cm, cod-end mesh size = 1.3 cm) (

Laboratory methods. A detailed examination of each sample was conducted to search for bivalves. Only living specimens were considered. Endolithic specimens (i.e., those growing within rocks or other hard substrates) were obtained by breaking rocks and shells, coral fragments, polychaete tubes, and rodoliths. Epifaunal specimens (i.e., species attached to a hard substrate) were obtained by scraping the surface of rocks. Semi-infaunal specimens (i.e., partially buried in the sediment but protruding above it) and infaunal specimens (< 4 mm) (i.e., those living buried in soft substrate) were obtained by screening the sandy sediment (

The absolute frequency of every species in each environment and site was estimated by calculating the ratio between the number of sites where that species was recorded and the total number of sites. A reference collection was set up with all the locality information in the Laboratory of Marine Ecosystems and Aquaculture at the Department of Ecology, University of Guadalajara, México. Voucher specimens were also deposited in this laboratory.

Analysis of the data. Only specimens recorded with the transect-quadrat method in the rocky intertidal and the adjacent shallow subtidal zones were used to evaluate sampling effort. Species accumulation curves were based on the cumulative number of species per quadrat. The expected richness was calculated using the nonparametric estimators Chao 2, Jackknife 1, and Jackknife 2. Plots were constructed with 10, 000 non-replacement iterations based on samples for each site and environment, using the software EstimateS v8 (

A species presence-absence matrix was constructed using information from the records obtained from the transect-quadrats, dredges, and direct search techniques on the rocky beaches (Olas Altas, Los Pinos, Casa del Marino, and Venados Island). Six taxonomic levels (species, genus, family, superfamily, order, and superorder) were considered based on the classification schemes of

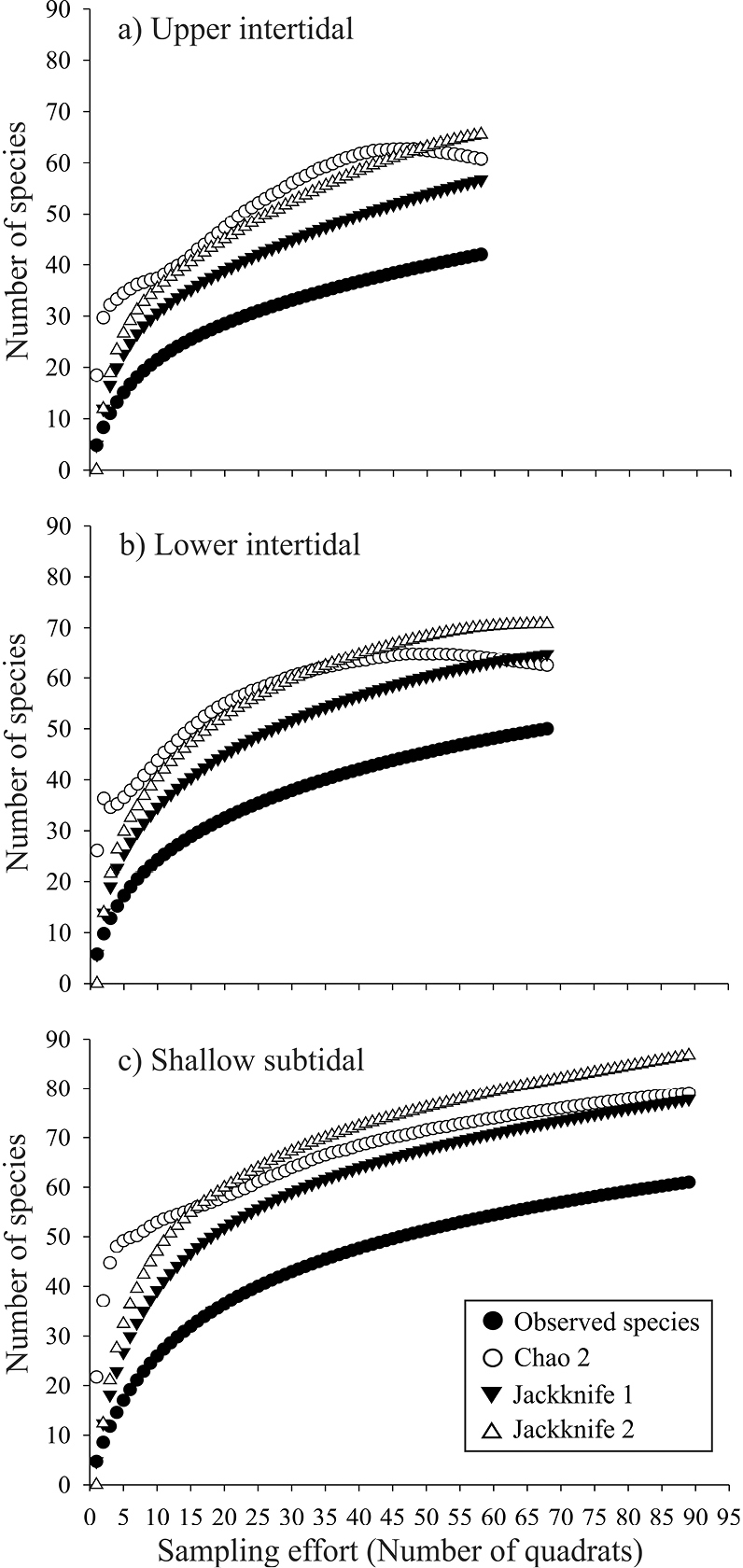

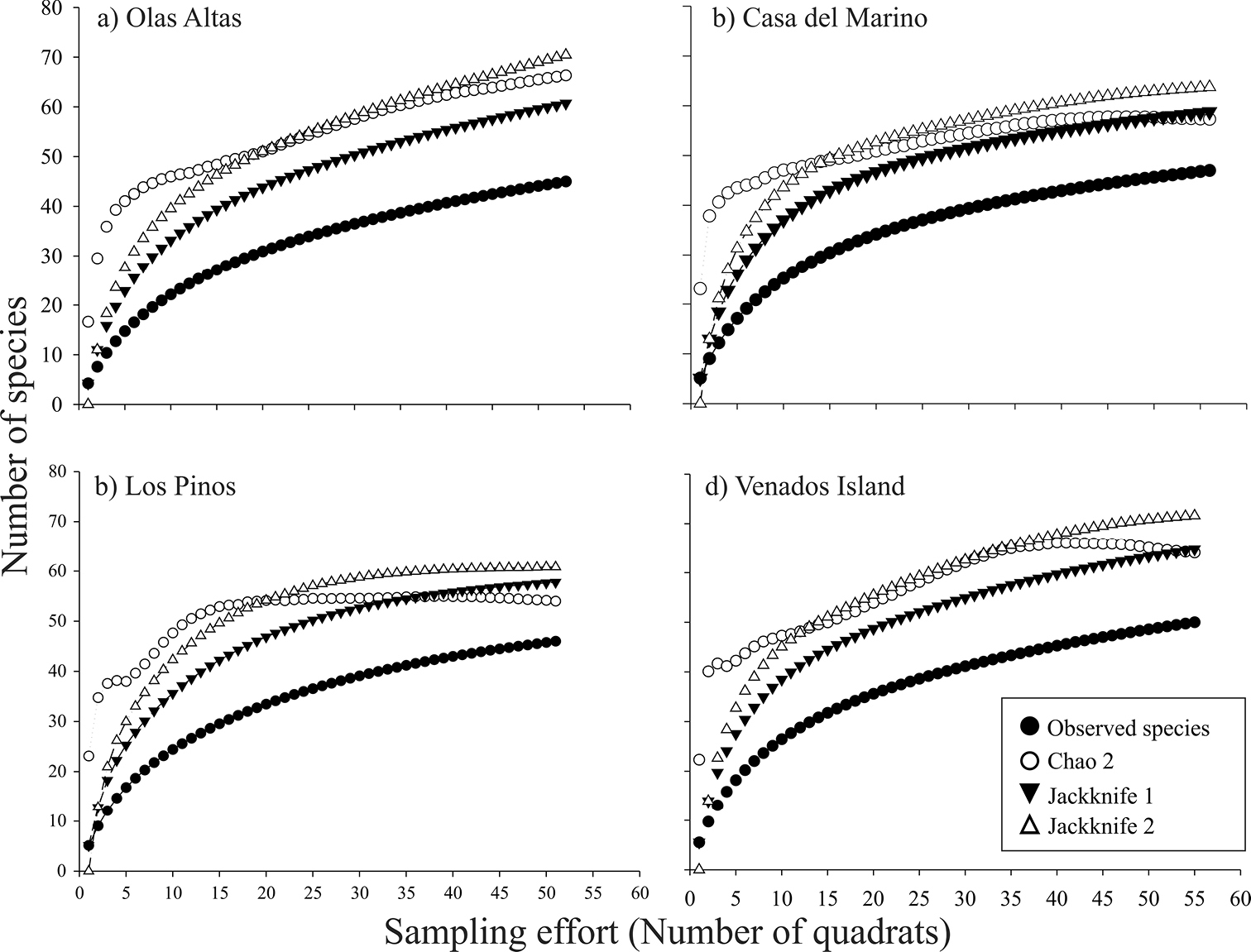

The species accumulation curves show a trend towards an symptote in all environments (Figure 2). The observed species representativeness with respect to the estimators Chao 2, Jackknife 1, and Jackknife 2 ranged between 64 and 80%, with Jackknife 1 always estimating the lowest expected richness, while Jackknife 2 always estimating the highest values. The species accumulation curves revealed a similar and more evident trend in the four sampling sites (Figure 3). The observed species representativeness ranged between 64 and 85% with respect to the estimators, with Jackknife 2 being the estimator that yielded the highest expected richness. Los Pinos and Casa del Marino possessed the highest species representativeness (≥ 79%), while Olas Altas had the lowest value (68-75%). A large number of unique (12–17) and duplicate (6–9) species were obtained in the three environments and the four sites (Table 1).

Observed and expected bivalves species accumulation curves, with nonparametric indices Chao 2, Jackknife 1, and Jackknife 2, in the three environments of Bahía de Mazatlán (a–c). Plots were constructed with 10, 000 non-replacement iterations.

Observed and expected bivalves species accumulation curves, with nonparametric indices Chao 2, Jackknife 1, and Jackknife 2, of four sites of Bahía de Mazatlán (a–d). Plots were constructed with 10, 000 non-replacement iterations.

Rarity of species in four sites and three environments in Bahía de Mazatlán, México.

| Rarity of species | Sites | Environments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olas Altas | Los Pinos | Casa Marino | Venados Island | Upper intertidal | Lower intertidal | Shallow subtidal | |

| Uniques | 16 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 17 |

| Duplicates | 6 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 8 |

A total of 21, 694 live bivalve specimens was recorded, representing 28 families, 55 genera, and 89 species (Table 2). The most diverse families were Mytilidae (14 species), Veneridae (10), and Arcidae (8). Ten families (35%) included only one species. The number of species increased from the upper (44) and lower intertidal (53) to the shallow subtidal (76). In addition, the numbers of unique species were 7 (upper), 4 (lower), and 18 (subtidal). The species richness was similar in the adjacent shallow subtidal zone of all beaches (28–36 species) except for Venados Island (55 species), which had the highest number of species restricted to this island (7) (Table 3).

Systematic list of species and sampling method used in the different environments of Bahía de Mazatlán, México. Q = quadrat & transect, D = dredge, DS = direct search, I = infaunal, E = epifaunal, S = semi-infaunal, En = endolithic; * = geographical range extensions; ** = species in only one environment; + = new record for the bay.

| Species | Environments | Life forms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper intertidal | Lower intertidal | Shallow subtidal | ||

| Mytilidae | ||||

| 1. Brachidontes adamsianus (Dunker, 1857) | Q | Q | Q, DS | E |

| 2. Brachidontes semilaevis (Menke, 1849) | Q | Q | Q | E |

| 3. Gregariella coarctata (P. P. Carpenter, 1857) | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| 4. Lioberus salvadoricus (Hertlein & Strong, 1946) | - | - | Q, DS | E |

| 5. Lithophaga (Diberus) plumula (Hanley, 1843) + | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| 6. Lithophaga (Labis) attenuata (Deshayes, 1836) | Q | Q | Q, DS | En |

| 7. Lithophaga (Myoforceps) aristata (Dillwyn, 1817) | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| 8. Lithophaga (Rupiphaga) hastasia Olsson, 1961 *, + | - | - | Q, DS | En |

| 9. Adula soleniformis (Olsson, 1961) *, + | - | - | Q, D, DS | En |

| 10. Botula cylista S. S. Berry, 1959 | - | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| 11. Leiosolenus spatiosus P. P. Carpenter, 1857 | - | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| 12. Modiolus americanus (Leach, 1815) | - | - | Q, D | E |

| 13. Modiolus capax Conrad, 1837 | - | Q | Q | E |

| 14. Septifer zeteki Hertlein & Strong, 1946 + | - | - | Q | E |

| Arcidae | ||||

| 15. Arca mutabilis (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) | Q | Q | D | E |

| 16. Arca pacifica (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) + | - | - | Q | E |

| 17. Acar bailyi Bartsch, 1931 | Q | - | - | E |

| 18. Acar gradata Broderip & G. B. Sowerby I, 1829 | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | E |

| 19. Acar rostae (S. S. Berry, 1954) | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | E |

| 20. Barbatia reeveana (d’Orbigny, 1846) | - | Q | - | E |

| 21. Barbatia illota (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) + | - | - | D | E |

| 22. Anadara formosa (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) | - | - | D, DS | S |

| Noetiidae | ||||

| 23. Arcopsis solida (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | E |

| Pteriidae | ||||

| 24. Pinctada mazatlanica (Hanley, 1856) | Q | Q | Q, DS | E |

| Isognomonidae | ||||

| 25. Isognomon (Melina) janus P. P. Carpenter, 1857 | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | E |

| 26. Isognomon (Melina) recognitus (Mabille, 1895) + | - | Q | - | E |

| Ostreidae | ||||

| 27. Ostrea conchaphila P. P. Carpenter, 1857 | Q | Q | Q, DS | E |

| 28. Saccostrea palmula (P. P. Carpenter, 1857) | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | E |

| 29. Striostrea prismatica (J. E. Gray, 1825) | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | E |

| Plicatulidae | ||||

| 30. Plicatula penicillata P. P. Carpenter, 1857 | Q | - | Q, D, DS | E |

| 31. Plicatulostrea anomioides (Keen, 1958) | Q | Q | Q, DS | E |

| Limidae | ||||

| 32. Limaria pacifica (d’Orbigny, 1846) | - | Q | Q, DS | E |

| Lucinidae | ||||

| 33. Liralucina approximata (Dall, 1901) | - | Q | - | S |

| 34. Ctena mexicana (Dall, 1901) + | Q | Q | Q, D | S |

| Carditidae | ||||

| 35. Carditamera affinis (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | I |

| 36. Cardites laticostatus (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) | Q | Q | Q, DS | I |

| Crassatellidae | ||||

| 37. Crassinella coxa Olsson, 1964 + | - | - | Q | S |

| 38. Crassinella ecuadoriana Olsson, 1961 | - | Q | Q | S |

| 39. Crassinella nuculiformis S. S. Berry, 1940 + | - | Q | Q | S |

| 40. Crassinella aff. pacifica (C. B. Adams, 1852) + | Q | Q | Q | S |

| Cardiidae | ||||

| 41. Laevicardium substriatum (Conrad, 1837) + | Q | - | - | I |

| Chamidae | ||||

| 42. Chama buddiana C. B. Adams, 1852 | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | E |

| 43. Chama coralloides Reeve, 1846 + | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | E |

| 44. Chama sordida Broderip, 1835 | Q | Q | Q, DS | E |

| 45. Chama cf. frondosa Broderip, 1835 | - | - | D | E |

| Lasaeidae | ||||

| 46. Kellia suborbicularis (Montagu, 1803) + | - | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| Mactridae | ||||

| 47. Mactrellona subalata (Mörch, 1860) *, + | - | - | D | I |

| 48. Mulinia pallida (Broderip & G. B. Sowerby I, 1829) + | - | - | D | I |

| Tellinidae | ||||

| 49. Strigilla (Strigilla) cicercula (R. A. Philippi, 1846) | - | Q | Q, D, DS | I |

| 50. Strigilla (Strigilla) dichotoma (R. A. Philippi, 1846) | Q | Q | Q | I |

| 51. Strigilla (Strigilla) ervilia (R. A. Philippi, 1846) *, + | Q | - | - | I |

| 52. Tellina (Laciolina) ochracea P. P. Carpenter, 1864 + | - | - | Q | I |

| 53. Tellina (Moerella) coani Keen, 1971 + | - | Q | Q, D | I |

| 54. Tellina (Moerella) felix Hanley, 1844 | - | Q | D | I |

| Donacidae | ||||

| 55. Donax (Chion) punctatostriatus Hanley, 1843 + | Q | Q | - | I |

| 56. Donax (Paradonax) gracilis Hanley, 1845 | - | Q | D | I |

| Semelidae | ||||

| 57. Cumingia lamellosa G. B. Sowerby I, 1833 | Q | Q | - | I |

| 58. Semele (Semele) cf. bicolor (C. B. Adams, 1852) | Q | - | - | I |

| 59. Semele (Semele) californica (Reeve, 1853) + | - | - | Q | I |

| 60. Semele (Semele) flavescens (A. A. Gould 1851) + | - | Q | - | I |

| 61. Semele jovis (Reeve 1853) + | Q | - | - | I |

| 62. Semele hanleyi Angas, 1879 + | Q | Q | Q | I |

| Ungulinidae | ||||

| 63. Diplodonta orbella (A. A. Gould, 1851) + | Q | - | Q, D, DS | En |

| 64. Diplodonta (Pegmapex) caelata (Reeve, 1850) | - | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| 65. Diplodonta (Timothynus) inezensis (Hertlein & Strong, 1947) + | - | - | Q | En |

| Veneridae | ||||

| 66. Chione subimbricata (G. B. Sowerby I, 1835) | Q | Q | Q, D | S |

| 67. Chione undatella (G. B. Sowerby I, 1835) + | - | - | Q | S |

| 68. Chioneryx squamosa (P. P. Carpenter, 1857) + | Q | Q | Q | S |

| 69. Paphonotia elliptica (G. B. Sowerby, 1834) | Q | - | - | S |

| 70. Periglypta multicostata (G. B. Sowerby, 1835) + | Q | - | - | S |

| 71. Megapitaria squalida (G. B. Sowerby, 1835) | - | - | Q | I |

| 72. Nutricola cf. humilis (P. P. Carpenter, 1857) | - | - | D | S |

| 73. Pitar cf. omissa (Pilsbry & Lowe, 1932) | - | - | Q | I |

| 74. Transennella modesta (G. B. Sowerby, 1835) + | - | - | Q | S |

| 75. Transennella cf. puella (P. P. Carpenter, 1864) | - | - | Q, D | S |

| Neoleptonidae | ||||

| 76. Neolepton (Neolepton) subtrigonum (P. P. Carpenter, 1857) | - | Q | Q, D, DS | S |

| Myidae | ||||

| 77. Sphenia fragilis (H. & A. Adams 1854) + | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| Corbulidae | ||||

| 78. Caryocorbula biradiata (G. B. Sowerby I, 1833) | Q | Q | Q | I |

| 79. Caryocorbula marmorata (Hinds, 1843) + | Q | Q | Q, DS | I |

| 80. Caryocorbula nasuta G. B. Sowerby I, 1833 | Q | - | Q, D | I |

| 81. Juliacorbula bicarinata G. B. Sowerby I, 1833 | Q | Q | Q | I |

| Petricolidae | ||||

| 82. Choristodon robustus (G. B. Sowerby I, 1834) + | - | - | D | En |

| 83. Petricola (Petricola) linguafelis (P. P. Carpenter, 1857) + | - | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| 84. Petricola (Petricolirus) californiensis Pilsbry & Lowe, 1932 + | - | - | DS | En |

| Phadidae | ||||

| 85. Parapholas calva (G. B. Sowerby I, 1834) + | - | - | Q | En |

| 86. Pholadidea (Hatasia) melanura (G. B. Sowerby I, 1834) | - | - | D | En |

| Hiatellidae | ||||

| 87. Hiatella arctica (Linnaeus, 1767) | Q | Q | Q, D, DS | En |

| Gastrochaenidae | ||||

| 88. Lamychaena truncata (G. B. Sowerby I, 1834) | - | - | Q, D | En |

| Lyonsidae | ||||

| 89. Entodesma brevifrons (G. B. Sowerby I, 1834) + | - | Q | Q, D, DS | I |

| Total sampling species richness (**) | 44 (7) | 53 (4) | 76 Q = 64 (10) D = 42 (7) DS = 38 (1) |

- |

| Total infaunal species richness | - | 26 | ||

| Total semi-infaunal species richness | - | 16 | ||

| Total endolithic species richness | - | 20 | ||

| Total epifaunal species richness | - | 27 | ||

Distribution of bivalve species at six sites in the Bahía de Mazatlán, México. Sites: OA = Olas Altas, LP = Los Pinos, CM = Casa del Marino, VI = Venados Island, MA = Malecon, ZD = Zona Dorada. Environments: UI = upper intertidal, LI = lower intertidal, SS = shallow subtidal, * = species recorded in only one site or environment. AF = absolute frequency, by sites and environment (for each environment, the number of sites where there was a species / total sites).

| Species | Sites and Environments | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA | LP | CM | VI | ZD | MA | AF | |||||||||||||||

| UI | LI | SS | UI | LI | SS | UI | LI | SS | UI | LI | SS | UI | LI | SS | UI | LI | SS | UI | LI | SS | |

| Acar bailyi | X | X | X | 0.5 | - | - | |||||||||||||||

| Acar gradata | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |||||||

| Acar rostae | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | ||||

| Adula soleniformis | X | X | - | - | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Anadara formosa | X | X | - | - | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Arca mutabilis | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||

| Arca pacifica* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Arcopsis solida | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | ||||||

| Barbatia illota* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Barbatia reeveana* | X | - | 0.2 | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Botula cylista | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.8 | ||||||||||||

| Brachidontes adamsianus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | ||||||

| Brachidontes semilaevis | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | |||||||

| Carditamera affinis | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | ||||

| Cardites laticostatus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ||||||||||

| Caryocorbula biradiata | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |||||||||||

| Caryocorbula marmorata | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||

| Caryocorbula nasuta | X | X | X | X | 0.2 | - | 0.5 | ||||||||||||||

| Chama buddiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.8 | |||||||

| Chama cf. frondosa* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Chama coralloides | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | |||||||

| Chama sordida | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | ||||||||||

| Chione subimbricata | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | ||||||||||

| Chione undatella* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Chioneryx squamosa | X | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||

| Choristodon robustus* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Crassinella aff. pacifica | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||

| Crassinella coxa* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Crassinella ecuadoriana | X | X | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||||

| Crassinella nuculiformis | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ctena mexicana | X | X | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | |||||||||||||

| Cumingia lamellosa | X | X | 0.2 | 0.2 | - | ||||||||||||||||

| Diplodonta caelata | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | 0.3 | 0.8 | |||||||||||

| Diplodonta inezensis | X | X | - | - | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Diplodonta orbella | X | X | X | X | X | 0.3 | - | 0.5 | |||||||||||||

| Donax gracilis | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Donax punctatostriatus | X | X | X | X | 0.3 | 0.3 | - | ||||||||||||||

| Entodesma brevifrons | X | X | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||||

| Gregariella coarctata | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.8 | ||||||||||

| Hiatella arctica | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Isognomon janus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | |||||

| Isognomon recognitus* | X | - | 0.2 | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Juliacorbula bicarinata | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||

| Kellia suborbicularis | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.8 | ||||||||||||

| Laevicardium substriatum* | X | 0.2 | - | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Lamychaena truncata | X | X | X | X | - | - | 0.7 | ||||||||||||||

| Leiosolenus spatiosus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | 0.5 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| Limaria pacifica | X | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.3 | |||||||||||||||

| Lioberus salvadoricus | X | X | - | - | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Liralucina approximata* | X | - | 0.2 | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Lithophaga aristata | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Lithophaga attenuata | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 | ||||||||

| Lithophaga hastasia* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Lithophaga plumula | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| Mactrellona subalata | X | X | - | - | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Megapitaria squalida* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Modiolus americanus | X | X | - | - | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Modiolus capax | X | X | X | X | X | - | 0.3 | 0.5 | |||||||||||||

| Mulinia pallida* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Neolepton subtrigonum | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | 0.3 | 0.8 | |||||||||||

| Nutricola cf. humilis* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Ostrea conchaphila | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | |||||

| Paphonotia elliptica* | X | 0.2 | - | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Parapholas calva* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Periglypta multicostata* | X | 0.2 | - | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Petricola californiensis* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Petricola linguafelis | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | - | 0.3 | 0.8 | |||||||||||

| Pholadidea melanura* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Pinctada mazatlanica | X | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||

| Pitar cf. omissa* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Plicatula penicillata | X | X | X | 0.2 | - | 0.3 | |||||||||||||||

| Plicatulostrea anomioides | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | ||||||

| Saccostrea palmula | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | ||||

| Semele californica | X | X | - | - | 0.3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Semele cf. bicolor* | X | 0.2 | - | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Semele flavescens | X | X | X | - | 0.5 | - | |||||||||||||||

| Semele hanleyi | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||

| Semele jovis* | X | 0.2 | - | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Septifer zeteki* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Sphenia fragilis | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| Strigilla cicercula | X | X | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||||

| Strigilla dichotoma | X | X | X | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||

| Strigilla ervilia* | X | 0.2 | - | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Striostrea prismatica | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | ||||

| Tellina coani | X | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.3 | |||||||||||||||

| Tellina felix | X | X | - | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Tellina ochracea* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Transennella cf. puella* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Transennella modesta* | X | - | - | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Exclusive species | 3 | - | 4 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | 7 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 2 | |||

| Total (enviroment by site) | 30 | 28 | 28 | 25 | 32 | 34 | 22 | 22 | 36 | 17 | 33 | 53 | 2 | 3 | 30 | 1 | 1 | 33 | |||

| Total epifaunal species richness | 17 | 15 | 10 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 17 | 22 | - | - | 10 | - | - | 11 | |||

| Total endolithic species richness | 6 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 13 | 2 | 7 | 14 | - | - | 14 | - | - | 13 | |||

| Total semi-infaunal species richness | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 10 | - | - | 3 | - | - | 2 | |||

| Total infaunal species richness | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||

| Total species richness by sites | 48 | 47 | 49 | 55 | 32 | 34 | |||||||||||||||

Several species of small size (5–10 mm) were recorded in rocky and sandy substrates: Crassinella coxa, Crassinella nuculiformis, Liralucina approximata, Ctena mexicana, Kellia suborbicularis, Neolepton subtrigonum, Nutricola cf. humilis, Pitar cf. omissa, Sphenia fragilis, Chioneryx squamosa, and Transennella cf. puella. Only three species were collected in the sandy intertidal environment: Strigilla cicercula, Strigilla dichotoma, and Donax punctatostriatus.

More species were recorded with the quadrat-transect technique in the shallow subtidal (64 species) than with either dredges (42 species) or direct searches (38 species). However, the species composition was different since some were collected only with quadrat-transects (10 species), dredges (7) or direct searches (1). The life-forms recorded included epifaunal (27), infaunal (26 species), endolithic (20), and semi-infaunal (16). Endolithic species were found in various hard substrates such as sedimentary rocks, corals, polychaete tubes, bivalve shells, and rodoliths. The rock-drilling bivalve Parapholas calva was found only in sedimentary rocks; all other species were found in two or more types of hard substrates.

Compared to previous studies in the region, this study includes 37 new records for Bahía de Mazatlán (Table 1), and geographic range extensions for four species: Lithophaga hastasia, Adula soleniformis, Mactrellona subalata, and Strigilla ervilia.

Twelve (13.5%) of the 89 species recorded were widely distributed in the bay (e.g., found in six sites), and 11 were recorded at three of the environments (UI, LI, and SS): Acar rostae, Carditamera affinis, Gregariella coarctata, Hiatella arctica, Lithophaga aristata, Lithophaga plumula, Leiosolenus spatiosus, Ostrea conchaphila, Saccostrea palmula, Striostrea prismatica, and Sphenia fragilis. However, a large number of species (27) were unique to one environment and sampling site. Only nine species were recorded in the three environments and in five or six sampling sites: Acar rostae, Arcopsis solida, Brachidontes adamsianus, Carditamera affinis, Isognomon janus, Ostrea conchaphila, Plicatulostrea anomioides, Saccostrea palmula, and Striostrea prismatica (Table 3).

There are several distribution patterns revealed by the life forms recorded in the different environments of Bahía de Mazatlán. Epifaunal bivalves were more frequent in the upper and lower rocky intertidal (12–17 species), followed by the endolithic species (1–8), whereas the number of infaunal species was very similar in all six sites (4–5), except for Venados Island. Similarly, epifaunal species dominated the shallow subtidal and intertidal zones (10–22), followed by the endolithic (7–14), infaunal (3–8) and semi-infaunal species (2–10) (Table 3).

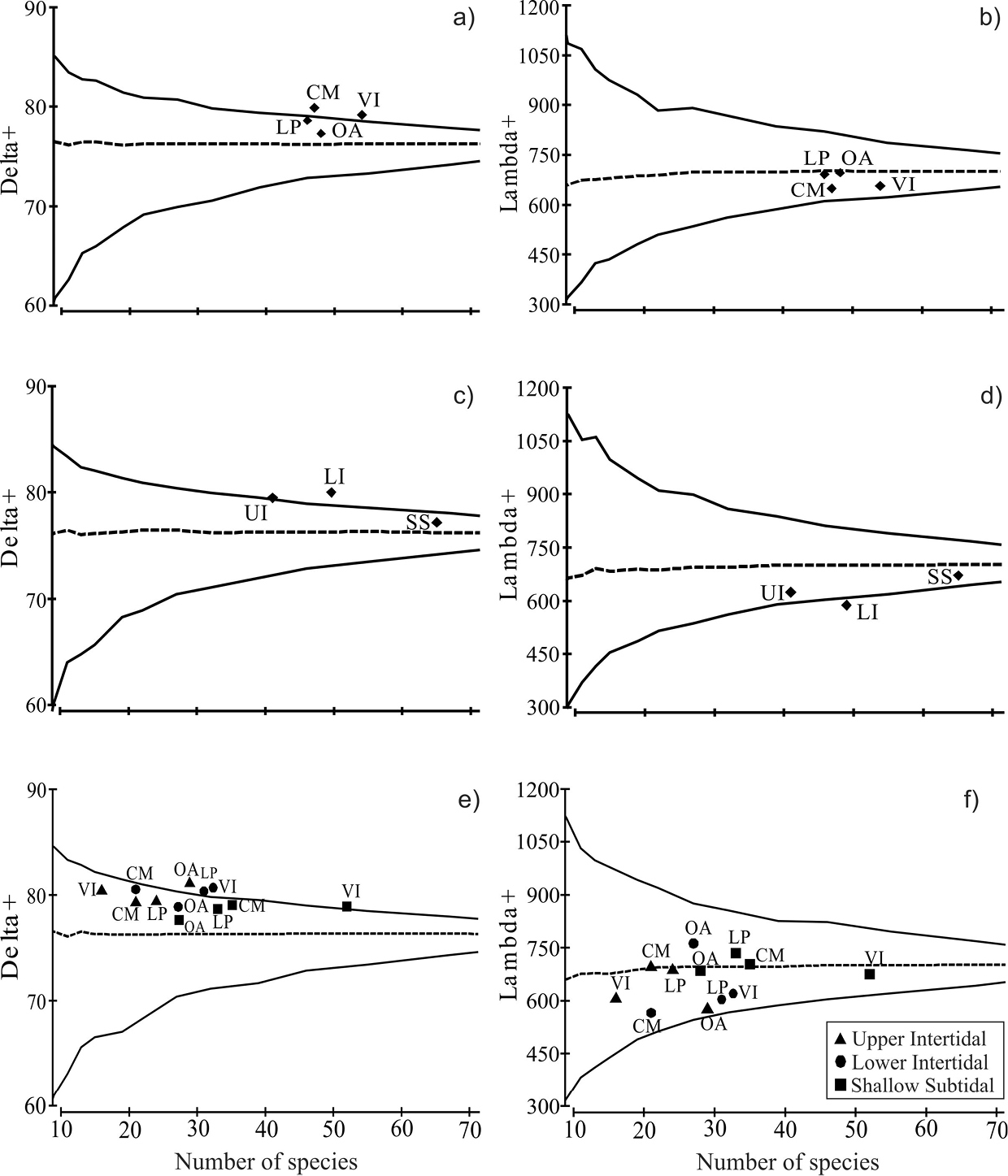

The average taxonomic distinctness analysis revealed complementary information on the bivalve assemblages recorded in the sampling sites and in the environments. The values of Δ+ for Los Pinos and Olas Altas fell within the probability funnel (e.g. within the confidence intervals of 95%, p>0.05), indicating a greater contribution to the mean taxonomic diversity of Bahía Mazatlan. However, values of Λ+ fell within the probability funnel for the four sites, suggesting that these are significantly representative of the bay’s bivalve assemblage (Figures 4a–b). On the other hand, the values of Δ+ for the SS zone and the values of Λ+ of the UI and SS fell within the confidence funnel, close to the bay’s mean taxonomic inventory (Figures 4c–d). Finally, in the case of the site-by-environment analysis, most sites fell within the Δ+ probability funnel (p>0.05), except for Olas Altas upper intertidal zone and Los Pinos and Venados Island lower intertidal zone (Figure 4e). Also the Λ+ values of all sites and environments fell within the funnel, i.e., all sites contribute significantly to the bay’s total taxonomic diversity (Figure 4f; Table 4).

Average taxonomic distinctness (∆+) and variation in taxonomic distinctness (Λ+) of bivalves assemblages in the four sites (a and b), in the three environments (c and d) and in the sites by environments of Bahía de Mazatlán (e and f). The continuous line shows confidence intervals at 95% and the dashed line shows values ∆+ & Λ+. The statistical significance of ∆+ & Λ+ were tested using 1, 000 permutations. Abbreviations as in Table 3.

Number of bivalve species, genera, families, superfamilies, orders and superorders registered in four sites in Bahía de Mazatlán, México. Sites: OA = Olas Altas, LP = Los Pinos, CM = Casa del Marino, VI = Venados Island. Environments: UI = upper intertidal, LI = lower intertidal, SS = shallow subtidal.

| Classification levels | Taxon | OA | LP | CM | VI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UI | LI | SS | UI | LI | SS | UI | LI | SS | UI | LI | SS | ||

| 1 | Species | 30 | 28 | 28 | 25 | 32 | 34 | 22 | 22 | 36 | 17 | 33 | 53 |

| 2 | Genera | 25 | 22 | 24 | 19 | 26 | 28 | 16 | 18 | 26 | 15 | 27 | 39 |

| 3 | Families | 14 | 14 | 17 | 13 | 19 | 14 | 11 | 13 | 19 | 11 | 18 | 24 |

| 4 | Superfamilies | 11 | 12 | 13 | 11 | 15 | 14 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 10 | 14 | 19 |

| 5 | Orders | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 12 |

| 6 | Superorders | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

The present work increased significantly (31%) the inventory of bivalve species of Bahía de Mazatlán to an updated total number of 132 species, including 37 new records (Table 5). According to these figures, the bay contributes 34% to the bivalve diversity of the southern Golfo de California (390 species) (

Previous studies in Bahía de Mazatlán, México. * = Species list not provided.

| Environments | Sampling method | Total species | Shared species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtidal (10–15 m) | Grab (Van Veen) | 3 | 2 | |

| Subtidal (3.5–27 m) | Grab (Van Veen) | 42 | 11 | |

| Subtidal | Trawls | 2 | 1 | |

| Rocky intertidal | Quadrats & transects | 15 | 14 | |

| Middle rocky intertidal | Direct search | 4 | 4 | |

| Lower rocky intertidal | Direct search | 12 | 11 | |

| Shallow subtidal (1–5 m) | Grab (Van Veen) & trawls | 22 | 12 | |

| Rocky– sandy intertidal | Quadrats | 7 | 5 | |

| Rocky– sandy intertidal | Quadrats | 13 | 5 | |

| Intertidal | Quadrats & transects | 9 | - | |

| Rocky– sandy intertidal | Transect band | 19 | 13 | |

| Total species previous studies | 83 | |||

| Total shared species | 40 | |||

| Rocky– sandy intertidal | Quadrats & transects | 60 | This study | |

| Sandy intertidal | Quadrats & transects | 3 | ||

| Subtidal (4–10 m) | Quadrats & transects | 64 | ||

| Subtidal (8–15 m) | Naturalist’s dredge | 42 | ||

| Subtidal (4–10 m) | Direct search | 38 | ||

| Total species present study | 89 | |||

| Total species in Bahía de Mazatlán | 132 | |||

Our surveys yielded a substantial increase in the number of infaunal (29%) and endolithic (23%) species of bivalves; most of them (67%) not recorded previously in the bay. This is particularly important since frequently the species richness of molluscs has been underestimated in ecological investigations due to two main factors that, alone or combined, contribute to incomplete inventories (

We also report range extension of four species previously known in other regions of the Eastern Pacific coast: Lithophaga hastasia (from Bahía de Banderas, Jalisco, to Perú); Strigilla ervilia (from Bahía de Tenacatita, Jalisco, to Salinas, Ecuador); Mactrellona subalata (from La Peñita, Nayarit to Tumbes, Perú); and Adula soleniformis (El Lagartillo, Los Santos, Panamá to Paita, Perú) (

A total of 83 additional species were collected during field work; these are not reported here because they were not living specimens however they were identified from complete and well preserved shells. Interestingly, most of these species (64) have not been recorded previously in the bay, thus raising the total inventory (living specimens plus empty shells) to 196 species. Many ecological investigations include the species recorded from empty mollusc shells assuming that they are components of the regional community (i.e.,

Some implications that emerge from the taxonomic identification of five bivalve taxa classified here as “cf.” (from the Latin confer which means “compare with”, that is, similar to and probably the same as, the parent taxon) are worth mentioning. These specimens corresponded to juvenile stages (Chama cf. frondosa, Semele cf. bicolor, Nutricola cf. humilis, Transennella cf. puella, and Pitar cf. omissa), which restricts their taxonomic determination because the keys and photographs in the literature consistently refer to adult specimens (i.e.,

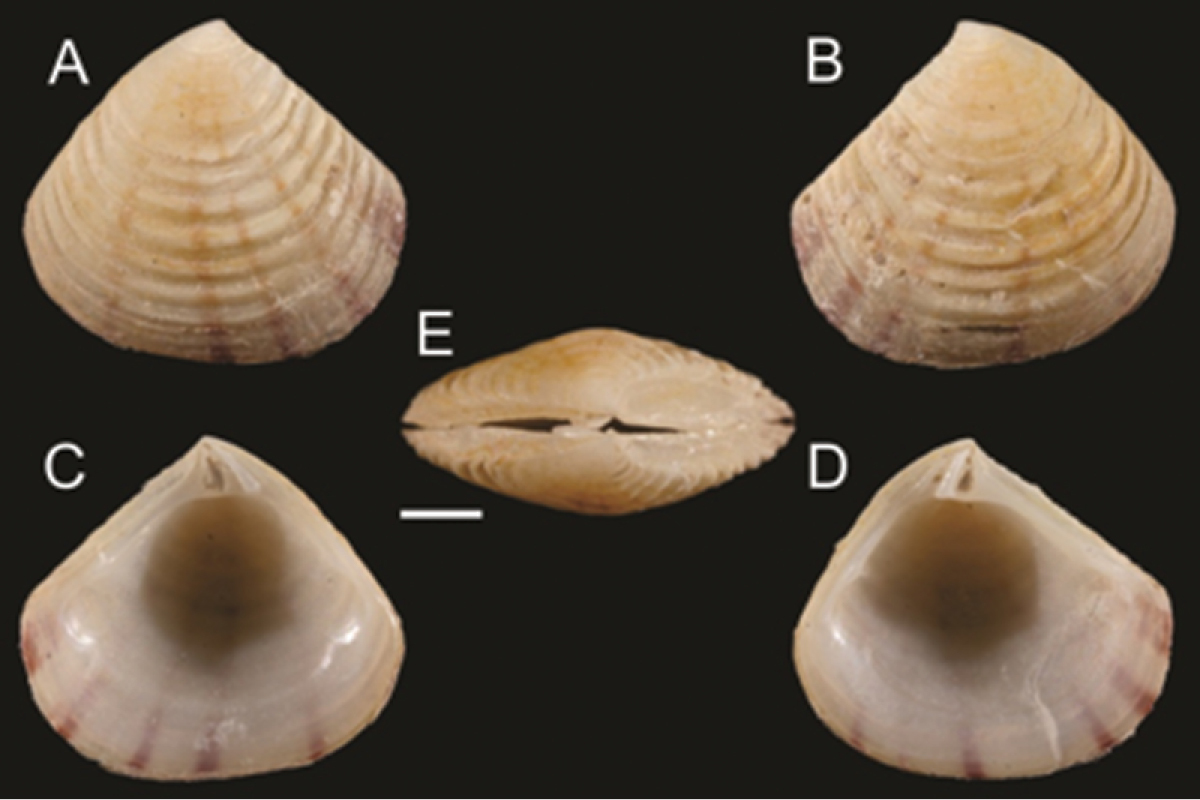

Crassinella aff. pacifica. Length = 4.92 mm A Exterior of right valve B Exterior of left valve C Interior of right valve D Interior of left valve E Dorsal view of both valves joined. Scale = 1 mm. Venados Island, Bahía de Mazatlán, México. LEMA-BI-14. Photography credit: Paul Valentich-Scott.

Some specimens of the rock oyster Striostrea prismatica did not show the thick lamellae on the outer shell surface which characterize this species. Instead, they exhibited tubular spines as Ostrea tubulifera. The spines are located on the outer edge of the shell, and the features of the inner surface match those of Striostrea prismatica. If only the analysis of morphological traits is considered, the problem could be explained as either hybridization between the two species–as this phenomenon is very common among oysters (

According to the different projections obtained with species accumulation curves, the expected total numbers of species is 32% (for the intertidal zone) and 57% (for the subtidal zone) higher than the number of species we actually collected. This difference relates to the large number of rare species recorded and it is a good estimator of the potential number of species expected in these environments at Bahía de Mazatlán. Even so, the species accumulation curves confirmed that our sampling effort was sufficient to calculate the theoretical total number of bivalve species in the bay.

Although different sampling techniques were used in the bay’s different environments, the sampling effort was estimated only for the quadrat-transect technique. Thus, whether all the bivalve species that inhabit the bay were collected in this study was not satisfactorily demonstrated. Some bivalves may be present either only in some seasons or impermanently, so these will not be recorded irrespective of the sampling intensity, which in turn is reflected in the sampling effort outcome (Figures 2, 3).

The high marine biodiversity of Golfo de California has been related to its irregular coastal geomorphology (i.e., open and protected bays and inlets, rocky and sandy beaches, estuaries, and numerous islands), the local dynamics of the surface currents and the seabed heterogeneity (

The characteristics of the Bahía de Mazatlán coastline provide a variety of benthic habitats to support a large number of bivalve species. A number of studies on the Mexican Pacific coast have shown that the high species richness and diversity of bivalve life forms are related to substrate heterogeneity, wave exposure and particle size of the sediments in the intertidal and shallow subtidal environments (

Our analysis combined data from three different sampling techniques, which was a major advantage, as the average taxonomic distinctness analysis is not affected by the various techniques and sampling effort used (

In this study, the combination of sites and environments provided better values of Δ+ and Λ+ when rocky shores and shallow subtidal adjacent zones were taken into consideration. This is because, although the three environments are clearly different from each other, all the sites contribute towards the taxonomic diversity of the bay. For example, Venados Island and Casa del Marino had the highest number of taxa in the shallow subtidal zone; Los Pinos and Venados Island, in the lower intertidal zone; and Olas Altas, in the upper intertidal zone. Theoretically, populations with a high genetic diversity have a high evolutionary potential or ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions (

The present work demonstrates that the bivalve fauna in Bahía de Mazatlán is well represented by various life forms (epifaunal, infaunal, semi-infaunal, and endolithic) in all the sites studied. Venados Island is an area protected by two government agencies; this is significant because it displayed high species richness and a large number of unique species. Since the bay is now a popular destination for tourists, efforts to preserve its ecosystems and species are essential, including those bivalves of economic importance such as the rock oyster Striostrea prismatica and the pearl oyster Pinctada mazatlanica. The latter species is on the Mexican Official List of Protected Species (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010).

The information on bivalve assemblages in Bahía de Mazatlán should be supplemented with analysis including an assessment of α, γ, and β diversity in order to determine their relative distribution at different spatial scales. A quantitative analysis investigating the relationship between bivalve assemblage structure and local and seasonal environmental parameters is also required. Such an analysis, would contribute to a comprehensive framework on the ecology of these bivalves, which is essential for further studies on the conservation of the bay.

The present research was conducted with the technical and financial support of the Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias (Universidad de Guadalajara), the Laboratorio de Invertebrados Bentónicos (ICMyL-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) led by Michel Hendrickx, and the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología de México (CONACyT). All the staff in the Laboratorio de Invertebrados Bentónicos offered us much help during field and laboratory work, especially José Salgado and Juan Toto. We are grateful to Arizbeth Alonso, Dafne Bastida, Arturo Santos, Vladimir Pérez, Rafael Negrete, Aurora Martínez, and Daniel Godard for their help during field work. Many bivalve specimens were identified or validated at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History under the supervision of Paul Valentich-Scott, who also reviewed and improved the preliminary version of this manuscript. We are very grateful to the Subject Editor Richard Willan and two anonymous referees for their comments that greatly improved earlier versions of the manuscript.