(C) 2013 Rafe M. Brown. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

We provide the first report on the herpetological biodiversity (amphibians and reptiles) of the northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range (Cagayan and Isabela provinces), northeast Luzon Island, Philippines. New data from extensive previously unpublished surveys in the Municipalities of Gonzaga, Gattaran, Lasam, Santa Ana, and Baggao (Cagayan Province), as well as fieldwork in the Municipalities of Cabagan, San Mariano, and Palanan (Isabela Province), combined with all available historical museum records, suggest this region is quite diverse. Our new data indicate that at least 101 species are present (29 amphibians, 30 lizards, 35 snakes, two freshwater turtles, three marine turtles, and two crocodilians) and now represented with well-documented records and/or voucher specimens, confirmed in institutional biodiversity repositories. A high percentage of Philippine endemic species constitute the local fauna (approximately 70%). The results of this and other recent studies signify that the herpetological diversity of the northern Philippines is far more diverse than previously imagined. Thirty-eight percent of our recorded species are associated with unresolved taxonomic issues (suspected new species or species complexes in need of taxonomic partitioning). This suggests that despite past and present efforts to comprehensively characterize the fauna, the herpetological biodiversity of the northern Philippines is still substantially underestimated and warranting of further study.

Biodiversity, Cagayan River Valley, Cordillera Mountain Range, Sierra Madre Mountain Range, Northern Philippines

The highly distinctive terrestrial vertebrate fauna of the northeastern Philippines has been the subject of intense interest, speculation, and debate since the first historical explorations of the northern extremes of the archipelago (

In the context of this biogeographical world view, islands like Luzon, at the tail ends of island chains and possible dispersal routes from the continental source (

Recent works suggest that the northern end of Luzon Island (Fig. 1) and the islands between Luzon and Taiwan (

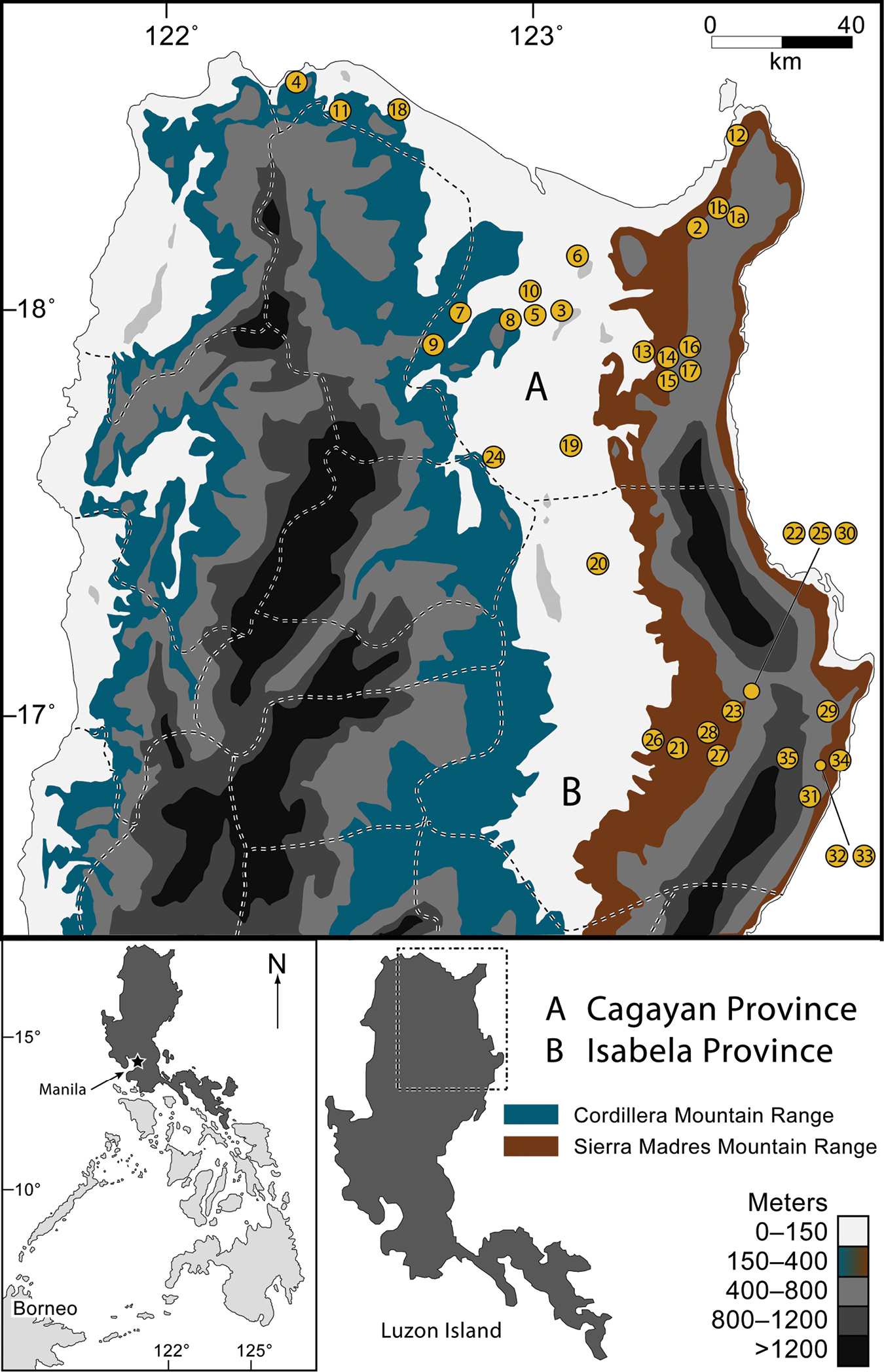

Map of northern Luzon Island, Philippines, with the Sierra Madre and Cordillera mountain ranges indicated (contour shading depicts elevational increments; see key, lower right). Provincial boundaries are indicated with dashed lines. Sampling localities marked with numbered circles, corresponding to localities listed in Table 1. The inset (bottom left) shows the location of Luzon Island (darkly shaded) within the Philippines.

In this paper we take the first step towards gaining a better understanding of the faunal communities of the northeastern-most extreme of Luzon by considering the amphibians and reptiles of the northern Sierra Madre Mountains (Fig. 1). We provide the first attempt to synthesize the known herpetological diversity of Cagayan and Isabela provinces (Fig. 1), northern Luzon Island (see also

Cagayan and Isabela Provinces: Geography and Landscape. Cagayan and Isabela provinces lie at the extreme northeastern portion of Luzon (Fig. 1), with land areas totaling more than 9, 000 and 10, 664 square kilometers, respectively. Cagayan contains 28 municipalities and 825 barangays (villages) while Isabela contains 35 municipalities and 1018 barangays. Their capital cities are Tuguegarao and Ilagan, respectively. Inhabited by six major enthnolinguistic groups (Ilocanos, Ibanags, Malauegs, Itawis, Gaddangs, and Aetas), together they are home to more than 2.6 million human residents (

Both Provinces are dominated by three strikingly distinct geographical and topographical features: the wide alluvial plains surrounding the Cagayan River valley, the northern extremes of a strikingly elongate north-south mountain range (The Sierra Madre; Figs 3

The Babuyan Island Group across the Balintang channel to the north of Luzon (Fig. 1) is included administratively in Cagayan Province; this biogeographically distinct region has recently been reviewed for its herpetofauna (

View of the north coast of Luzon, along the boundary between west Cagayan Province and Ilocos Province (fig. 1). Photo: JS.

View of the forested west coast of Isabela Province (Dinapique). Photo: MVW.

View of the Sierra Madre from the west, at the Municipality of Cabagan, Barangay Garita (Isabela Province). Photo: MVW.

View of the northeast coast of Luzon from the foothills of Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga. Note northern end of the Sierra Madre at right and Palaui Island in the background to the right. Photo: RMB.

Ultrabasic forests above 1200 m at Barangay Diddadungan, Palanan, northern Isabela Province. Photo: MVW

View south of the northern Sierra Madre (from peak of Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga, Cagayan Province). Photo: LJW.

Mt. Cagua, Cagayan Province, with rice fields on the outskirts of Barangay Magrafil in the foreground. Photo: RMB.

We surveyed amphibian and reptile diversity at numerous sites throughout Cagayan and Isabela provinces (Table 2) using standardized sampling techniques (

Sampling Locations. Data presented here include results of our own surveys (Table 1) and a variety of collections, both intensive and incidental, from major U.S. Museum collections (see acknowledgements). In addition, an extensive series of collections housed at the USNM (field work of R. I. Crombie), KU and PNM (field work of ACD and surveys of MVW, EJ, and DR) targeted several localities to the south, in central Cagayan Province and Isabela Province. To be as comprehensive as possible in our treatment of Cagayan and Isabela, we include all of these records here, with the caveat that methods of surveying herpetological communities most likely differed among collection efforts and locations.

Cagayan and Isabela localities where amphibian and reptile specimens have been collected or observed (see Materials and Methods).

| Location | Municipality | Barangay/Barrio | GPS coordinates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cagayan | ||||

| 1a | Gonzaga | Barangay Magrafil | Mt. Cagua crater | 18.213N, 122.110E |

| 1b | Gonzaga | Barangay Magrafil | Mt. Cagua low elevation | 18.236N, 122.104E |

| 2 | Gonzaga | Barangay Santa Clara | Purok 7 | 18.228N, 122.060E |

| 3 | Gattaran | Barangay Nassiping | 18.054N, 121.641E | |

| 4 | Santa Praxedes | Taggat Forest Reserve | 18.580N, 121.010E | |

| 5 | Lasam | Lasam Centro | 18.051N, 121.600E | |

| 6 | Lasam | Battalan Barrio | 18.171N, 121.723E | |

| 7 | Lasam | Cabatacan Barrio | 18.072N, 121.480E | |

| 8. | Lasam | Alannay Barrio | 18.053N, 121.551E | |

| 9 | Lasam | Vintar Barrio | 18.045N, 121.43E | |

| 10 | Lasam | San Pedro | 18.081N, 121.597E | |

| 11 | Santa Ana | Barangay San Vicente, | Sitio Angib | 18.490N, 121.168E |

| 12 | Santa Ana | Santa Ana Centro | 18.482N, 122.1569E | |

| 13 | Baggao | Barrio Santa Margarita | 17.923N, 121.960E | |

| 14 | Baggao | Road between Barrio San Miguel and Barrio Imurung | 17.914N, 121.988E | |

| 15 | Baggao | Barrio Via | Vicinity of hot springs on bank of Ital river | 17.887N, 121.986E |

| 16 | Baggao | Barrio San Miguel | 17.917N, 122.000E | |

| 17 | Baggao | Barrio Imurung | 17.898N, 122.001E | |

| 18 | Pamplona | ca. 4 km NW of Abulug River Bridge | 18.464N, 121.339E | |

| 19 | Solana | Barrio Nabbutuan | 17.658N, 121.683E | |

| 20 | Peñablanca | Barangay Malibabag | Callao Caves area | 17.677N, 121.8444E |

| Isabela | ||||

| 21 | Cabagan | Barangay Garita, Mitra Ranch | 17.417N, 121.8231E | |

| 22 | San Mariano | Barangay Binatug | 16.954N, 122.0669E | |

| 23 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan, Apaya Creek area | Sitio Apaya | 17.029N, 122.1928E |

| 24 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan, Dunoy Lake area | Sitio Dunoy | 16.995N, 122.1579E |

| 25 | San Mariano | Barangay Del Pilar | 16.8592N, 122.104E | |

| 26 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan, Dibanti Ridge, Dibanti River area | 17.015N, 122.2036E | |

| 27 | San Mariano | Barangay Alibadabad | 16.964N, 122.0451E | |

| 28 | San Mariano | San Jose | 16.934N, 122.1275E | |

| 29 | San Mariano | Barangay Disulap | 16.963N, 122.1250E | |

| 30 | Palanan | Barangay Didian | Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park | 16.970N, 122.4122E |

| 31 | San Mariano | Barangay Dibuluan | Catalangan River | 17.024N, 122.1794E |

| 32 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Dyadyadin, ultrabasic forest | 16.798N, 122.3922E |

| 33 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Pangden, lowland dipterocarp forest | 16.833N, 122.4181E |

| 34 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Limestone forest near Magsinaraw cave | 16.941N, 122.4536E |

| 35 | Palanan | Barangay Diddadungan | Coastal habitat, Divinisa | 16.834N, 122.4319E |

| 36 | Palanan | Barangay Didian | Dipagsanghan, lowland dipterocarp forest | 16.879N, 122.3447E |

| 37 | Maconacon | Barangay Reina Mercedes | Blos River | 17.508N, 122.1916E |

Amphibians (anurans) and reptiles (lizards , snakes, turtles, and crocodiles) from Cagayan Province, andIsabela Province (to the south; together the two provinces make up the northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range, of Luzon Island; Fig. 1). N = new provincial record (observed during this study, with voucher specimen). P = previously reported literature records for Cagayan or Isabela provinces (with vouchered specimens of photographic evidence deposited in museum collections). O = new observation (no voucher specimens collected). R = Range extension within Cagayan and/or Isabela Province. * = Luzon faunal region (

| AMPHIBIA | Cagayan | Isabela |

| Bufonidae | ||

| Rhinella marina (Linnaeus, 1758) | N | P |

| Ceratobatrachidae | ||

| Platymantis cagayanensis Brown, Alcala & Diesmos, 1999* | P, R | N |

| Platymantis corrugatus (Duméril, 1853) | N | N |

| Platymantis cornutus (Taylor, 1922)* | N | N |

| Platymantis polillensis (Taylor, 1922)* | N | |

| Platymantis pygmaeus Alcala, Brown & Diesmos, 1998* | N | P |

| Platymantis sierramadrensis Brown, Alcala, Ong & Diesmos, 1999* | N | P |

| Platymantis taylori Brown, Alcala & Diesmos, 1999* | P | |

| Platymantis sp. “Yokyok” * | N | N |

| Platymantis sp.2 “Cheep-cheep” * | N | N |

| Platymantis sp.3 “See-yok” * | N | N |

| Platymantis sp. | N | N |

| Dicroglossidae | ||

| Fejervarya moodiei (Taylor, 1920) | N | |

| Fejervarya vittigera (Wiegmann, 1834) | N | N |

| Hoplobatrachus rugulosus (Wiegmann, 1834) | N | N |

| Limnonectes macrocephalus (Inger, 1954)* | N | P |

| Limnonectes woodworthi (Taylor, 1923)* | N | N |

| Occidozyga laevis (Günther, 1859) | P | N |

| Microhylidae | ||

| Kaloula kalingensis Taylor, 1922* | N | P |

| Kaloula rigida Taylor, 1922* | N | N |

| Kaloula picta (Duméril & Bibron, 1841) | N | N |

| Kaloula pulchra Gray, 1825 | N | N |

| Ranidae | ||

| Hylarana similis (Günther, 1873)* | N | P |

| Sanguirana luzonensis (Boulenger, 1896)* | N | P |

| Sanguirana tipanan (Brown, McGuire & Diesmos, 2000)* | P | |

| Rhacophoridae | ||

| Philautus surdus (Peters, 1863) | N | N |

| Polypedates leucomystax Gravenhorst, 1829 | N | N |

| Rhacophorus pardalis Günther, 1859 | N | N |

| Rhacophorus appendiculatus (Günther, 1858) | N | |

| REPTILIA (Lizards) | ||

| Agamidae | ||

| Bronchocela marmorata Gray, 1845 | N | N |

| Draco spilopterus (Wiegmann, 1834) | N, P | N |

| Gekkonidae | ||

| Cyrtodactylus philippinicus (Steindacher, 1867) | N | N |

| Gehyra mutilata (Wiegmann, 1834) | O | N |

| Gekko gecko (Linnaeus, 1758) | N | N |

| Gekko kikuchii (Oshima, 1912) | N | N |

| Hemidactylus frenatus Duméril & Bibron, 1836 | O | N |

| Hemidactylus platyurus (Schneider, 1792) | O | |

| Hemidactylus stejnegeri Ota & Hikida, 1989 | N | |

| Lepidodactylus cf. lugubris (Duméril & Bibron, 1836) | N | N |

| Luperosaurus cf. kubli Brown, Diemsos & Duya, 2007* | N | N |

| Pseudogekko compressicorpus (Taylor, 1915) | N | |

| Scincidae | ||

| Brachymeles bicolor (Gray, 1845)* | N | P |

| Brachymeles bonitae Duméril & Bibron, 1839 | N | N |

| Brachymeles kadwa Siler & Brown, 2010* | P | |

| Brachymeles muntingkamay Siler, Rico, Duya & Brown, 2009* | N | |

| Eutropis cumingi (Brown & Alcala, 1980) | N | N |

| Eutropis multicarinata borealis Brown & Alcala, 1980 | N | N |

| Eutropis multifasciata (Kuhl, 1820) | O | N |

| Lamprolepis smaragdina philippinica Mertens, 1829 | N | N |

| Lipinia cf. vulcania Girard, 1857 | N | |

| Otosaurus cumingi Gray, 1845 | N | N |

| Pinoyscincus abdictus aquilonius (Brown & Alcala, 1980) | N | N |

| Parvoscincus decipiens (Boulenger, 1895)* | N | N |

| Parvoscincus cf. decipiens* | N | N |

| Parvoscincus leucospilos (Peters, 1872)* | O | N |

| Parvoscincus steerei (Stejneger, 1908) | N | N |

| Parvoscincus tagapayao (Brown, McGuire, Ferner & Alcala, 1999)* | N | N |

| Varanidae | ||

| Varanus marmoratus (Wiegmann, 1834)* | N | P |

| Varanus bitatawa Welton, Siler, Bennet, Diesmos, Duya, Dugay, Rico, Van Weerd & Brown, 2010* | P, R | P |

| REPTILIA (Snakes) | ||

| Colubridae | ||

| Ahaetulla prasina preocularis (Taylor, 1922) | N | N |

| Boiga cynodon (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Boiga dendrophila divergens Taylor, 1922* | N | |

| Boiga philippina (Peters, 1867)* | N | |

| Calamaria bitorques Peters, 1872* | N | N |

| Calamaria gervaisi Duméril & Bibron, 1854 | N | N |

| Coelognathus erythrurus manillensis (Jan, 1863)* | N | P |

| Cyclocorus lineatus lineatus (Reinhardt, 1843)* | N | N |

| Dendrelaphis luzonensis Leviton, 1961* | N | N |

| Dendrelaphis marenae Vogel & van Rooijen, 2008 | N | N |

| Dryophiops philippina Boulenger, 1896 | N | N |

| Gonyosoma oxycephalum (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Hologerrhum philippinum Günther, 1858* | N | N |

| Lycodon capucinus (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Lycodon muelleri Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854* | N | |

| Lycodon solivagus Ota & Ross, 1984* | N | |

| Oligodon ancorus (Girard, 1858) * | N | |

| Psammodynastes pulverulentus (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Pseudorhabdion cf. mcnamarae (Taylor, 1917)* | N | |

| Pseudorhabdion cf. talonuran Brown, Leviton & Sison, 1999* | N | |

| Ptyas luzonensis (Günther, 1873) | N | |

| Rhabdophis spilogaster (Boie, 1827) | N | N |

| Tropidonophis dendrophiops (Günther, 1883) | N | N |

| Elapidae | ||

| Hemibungarus calligaster (Wiegmann, 1835)* | N | |

| Naja philippinensis Taylor, 1922; Ophiophagus hannah (Cantor, 1836) | NN | |

| Homolopsidae | ||

| Cerberus schneideri (Schlegel, 1837) | N | |

| Lamprophiidae | ||

| Oxyrhabdium leporinum leporinum (Günther, 1858)* | N | |

| Pythonidae | ||

| Python reticulatus (Schneider, 1801) | N | P |

| Typhlopidae | ||

| Ramphotyphlops braminus (Daudin, 1803) | N | N |

| Typhlops ruficaudus (Gray, 1845)* | N | |

| Typhlops sp. 1* | N | |

| Typhlops sp. 2* | N | |

| Viperidae | ||

| Trimereserus flavomaculatus (Gray, 1842) | N | N |

| Tropidolaemus subannulatus (Gray, 1842) | O | |

| REPTILIA (Turtles) | ||

| Geomydidae | ||

| Cuora amboinensis amboinensis (Daudin, 1802) | P | N |

| Trionychidae | P | P, O |

| Pelochelys cantorii Gray, 11864 | P | P, O |

| Cheloniidae | ||

| Caretta caretta (Linnaaeus, 1758) | O | |

| Chelonia mydas (Linnaaeus, 1758) | O | |

| Eretmochelys imbricata (Linnaaeus, 1766) | O | |

| Crocodylidae | ||

| Crocodylus mindorensis Schmidt, 1935 | P, O | P, O |

| Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801 | P, O | P, O |

The forested edge of the Mt. Cagua volcanic crater with the northern Sierra Madre in the background. Photo: RMB.

Natural grassland area on the edge of Mt. Cagua volcanic crater. Photo: JS.

Appearance of lower edge of cloud forest, 1250 m, Mt. Cagua. Photo: RMB.

Volcanic vent on the forested floor of the Mt. Cagua crater. Photo: LJW.

Appearance of Mt. Cagua cloud forest below the canopy at 1250 m asl. Photo: RMB.

Mature forest at Location 1a in the crater floor of Mt. Cagua. Photo: JS.

Unnamed waterfall at Location 1a in the crater floor of Mt. Cagua. Photo: JS.

Streamside habitat typical of Limnonectes macrocephalus, Hylarana similis, Sanguirana luzonensis, and Platymantis sp. 2 (near Location 1a). Photo: LJW.

Signs of illegal timber poaching on the boundary of the Mt. Cagua protected area, Location 2. Photo: RMB.

We document 101 species of amphibians and reptiles from Cagayan and Isabela provinces, including 29 frog species, 30 lizards, 35 snakes, two freshwater turtles, three marine turtles, and two crocodilian taxa (Table 2). Taken together this diversity represents approximately 35% percent of the total Philippine herpetofauna (approximately 350 species;

Family Bufonidae

Rhinella marina (Linnaeus, 1758)

Rhinella marina (Fig. 18) is a non-native species that may have originally been introduced to the Philippines during the industrial revolution and the major sugar cane agricultural production boom on the central Philippine island of Negros (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330585; Location 5: USNM 498512–15, PNM 7424.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307440.

Rhinella marina at San Mariano (Location 23; specimen not collected); Photo: ACD.

Family Ceratobatrachidae

Platymantis cagayanensis Brown, Alcala & Diesmos, 1999

Originally described from extreme northwest Cagayan Province at the Municipality of Santa Praxedes along the border with Ilocos Norte Province (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330300–01; Location 1b: KU 330302–26; Location 3: PNM 7614–24; Location 4: CAS 207447–50 (paratypes); PNM 6691 (holotype), 6692–93 (paratypes).

Isabela Province—Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Platymantis cagayanensis (KU 330716) from mid-elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Note diagnostic yellow coloration of upper iris. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis corrugatus (Duméril, 1853)

Platymantis corrugatus (Fig. 20), as presently recognized, is a widespread endemic species found throughout the archipelago. There is considerable color pattern variation, but the species can be generally diagnosed by its medium body size, some form of a dark (gray, brown, or black) facial mask, and elongate tubercular ridges running along the dorsal surface. We observed this species at many locations calling most intensively at sunset (1800–1900 hr) after which it only called intermittently. The species commonly calls from beneath some kind of ground cover (leaf of other debris) on the forest floor. Its call sounds to the human ear like a raspy “whaaah…whaaah.”

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330249–54: Location 1b: KU 330255–63; Location 11: PNM 6453; Location 15: USNM 498730.

Isabela Province—Location 30: PNM 6448, MVW photo voucher.

Platymantis corrugatus (KU 330255) from mid-elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b) Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis cornutus (Taylor 1922)

Originally described on the basis of a single specimen from Balbalan, Kalinga, in the northern Cordillera Mountain Range (holotype CAS 231501;

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330362–89; Location 1b: KU 330390–92.

Platymantis cornutus (KU 330390) from mid-elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Note diagnostic yellow inguinal coloration and white infratympanic tubercle. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis polillensis (Taylor 1922)

Platymantis polillensis (Fig. 22) is a small, herbaceous-layer specializing arboreal species encountered most often in ferns and shrubs colonizing disturbed forest edges, secondary growth forest, forest gaps, and tree falls. Previously considered “Critically Endangered, ” or “Endangered” (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330234–35; Location 1b: KU 330236–38.

Isabela Province—Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Female Platymantis polillensis (KU 330235) from mid elevation of Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Platymantis pygmaeus Alcala, Brown & Diesmos, 1998

Platymantis pygmaeus (Fig. 23) was originally described from Palanan, Isabela Province, and is now known to be widespread and abundant in Bulacan, Quezon, Aurora, Kalinga, Isabela, Cagayan, and Ilocos Norte provinces (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330239–43; Location 1b: KU 330244–48; Location 13: PNM 7800–01; Location 33: no specimen (MVW photo voucher).

Isabela Province—Location 30: CAS 204762–66 (paratypes), PNM 6255 (holotype), 7792–99; Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Platymantis pygmaeus (specimen not collected) at San Mariano (Location 33). Photo: MVW.

Platymantis sierramadrensis Brown, Alcaka, Ong & Diesmos, 1999

Platymantis sierramadrensis was described on the basis of specimens from Barangay Umiray, Municipality of General Nakar, Quezon Province (holotype PNM 6465), from Aurora Province (paratypes 204738, 204742–45), and other, non-type material from Palanan, Isabela Province (CAS 204739, 204740, CAS 204741). Subsequent confusion in identification of Platymantis sierramadrensis has involved a suspicion that two separate taxa may have been attributed to this species, a confusion that may have undermined the type description (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330637–51.

Isabela Province—Location 30: CAS 204739–41; Location 36: PNM 6461–63, 6470–74.

Platymantis taylori Brown, Alcala, Diesmos, 1999

Since the time of its discovery (

Long overdue for a conservation status revision, we categorize this species as “Data Deficient” (DD) because (1) it has been recorded only once and no repeat surveys to the immediate or surrounding areas have been undertaken to determine the extent of its range, and (2) there is no evidence that this taxon requires intact, low-elevation forest and no evidence to suggest that it is range-restricted. Thus, there is no way to determine whether continued degradation of lowland coastal forests in Palanan will adversely affect this species. Originally characterized as “common and widespread” at the original collection site (

Isabela Province—Location 21: PNM 8676; Location 26: ACD specimens deposited in PNM; Location 30: CAS 207440–46 (paratypes), PNM 6684, 8659–74, 8953.

Platymantis taylori (PNM 8676) from San Mariano (Location 29). Photo: ACD.

Platymantis sp. 1 “Yokyok”

This distinctive form (Fig. 25) is now known from two sites in Cagayan and Isabela provinces (both between 400 and 500 m in disturbed forested habitats). We suspect that this possible undescribed species is much more widespread and will be frequently encountered if surveys can be conducted in intervening localities. This terrestrial species is slightly smaller than the morphologically similar Platymantis cagayanensis and Platymantis sp. 3 “seeyok, ” and calls with a long pulse train, sounding to the human ear like “Yok-yok-yok-yok….”

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330628–35.

Isabela Province—Location 3: KU 307608–09, 327587; Location 30: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Platymantis sp. 1 (“Yokyok;” KU 330628) from lower elevation Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga, below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis sp. 2 “Cheep-cheep”

We encountered another potentially distinct species (Fig. 26) of Platymantis at both high and low elevation sites on Mt. Cagua, Municipality of Gonzaga. The suspected new species appears phenotypically most similar to Platymantis lawtoni from Sibuyan Island (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330588–330600; Location 1b: 330601–615.

Platymantis sp. 2 (“Cheep-cheep;” KU 330606) from the crater of Mt. Cagua, Location 1a. Photo: RMB.

Platymantis sp. 3 “See-yok”

This suspected new species (Figs 27, 28) was first observed in Old Balbalan Town (Kalinga Province; RMB and ACD, personal observations) and has since been recorded at many sites throughout central and northern Luzon. Morphologically most similar to Platymantis cagayanensis, this species can reliably be identified by its silvery iris (versus the bright yellow-orange iris in Platymantis cagayanensis) and by distinctive advertisement call, sounding to the human ear like “seee-yok…seee-yok” (Brown et al. unpublished data).

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330618–27, PNM 8678–90.

Isabela Province—Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Platymantis sp. 3 (“See-yok;” specimen not collected) from Location 36. Photo: MVW.

Another color variant of Platymantis sp. 3 (“See-yok;” KU 330627) from mid-evelation, Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Platymantis sp.

Without genetic data, information on mating calls, and/or photographs in life, numerous museum specimens of ground-dwelling, medium sized, dorsally tuberculate members of the genus Platymantis cannot confidently be identified to species. Many have previously been identified by field collectors as Platymantis dorsalis on the basis of generalized morphological similarity to that southern Luzon (type locality: Laguna Bay) species (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330653–713; Location 1b: KU 330714–16; Location 6: USNM 498524–28; Location 13: USNM 498692–93; Location 15: USNM 498731–34.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307611–17.

Family Dicroglossidae

Fejervarya moodiei (Taylor 1920)

Fejervarya moodiei (Fig. 29) is a widespread, endemic estuarine specialist that can be found in a variety of coastal areas including brackish water swamps. Previously considered conspecific with the widespread Southeast Asian species Fejervarya cancrivora, recent genetic evidence suggests that the Philippine populations are genetically distinct; the available name for the Philippine population is Fejervarya moodiei (

Cagayan Province—Location 5: PNM 7424; Location 11: PNM 5654, Location 12: PNM 5654, 5675.

Fejervarya moodiei (ACD specimen deposited in PNM) from Ilocos Norte Province. Photo: ACD.

Fejervarya vittigera (Wiegmann, 1834)

Fejervarya vittigera is a widespread, low elevation species typically observed in highly disturbed areas with standing water (rice fields, ponds and lakes) or along small, denuded streams near coastal areas or canals bordering agricultural areas. Our specimens were found along muddy stream banks in disturbed forests at the edge of agricultural plantations. Although until now this species has always been considered “Least Concern” (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330225; Location 5: USNM 498529–45, 498973–80; PNM 6256–60; Location 6: USNM 498546; Location 11: USNM 498649; Location 14: USNM 498761–62; Location 19: PNM 6191–93.

Isabela Province—Location 21: 307469.

Hoplobatrachus rugulosus (Wiegmann, 1834)

This introduced species (Fig. 30) was first detected in Laguna province in 1996 (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330225; Location 3: PNM 9448.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307488.

Hoplobatrachus rugulosus from Minanga (ACD 3159, deposited in PNM). Photo ACD.

Limnonectes macrocephalus (

The Luzon fanged frog Limnonectes macrocephalus (Fig. 31) inhabits rivers and streams from sea level up to high elevation forests. Although targeted by humans for food and potentially at risk from predation and competition from invasive species (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330425–54; Location 1b: KU 330455–69; Location 13: USNM 498704–10, PNM 5888–93; Location 15: USNM 498750–57, 498967–70.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307493–94, 307498–99, 307501–503; Location 22: KU 307506–18; Location 23: KU 327509–17; Location 30: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Limnonectes macrocephalus (specimens not collected from Dipagsanghan, Location 36. Photo: MVW.

Limnonectes woodworthi (

Limnonectes woodworthi (Fig. 32) is a commonly encountered stream frog in the mountains of southern Luzon and throughout the Bicol Peninsula (Diesmos 1998;

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330227; Location 1b: KU 330226; Location 4: PNM 7523; Location 12: PNM 7522.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307491–92, 307496–97, 307500; Location 23: KU 326471–75.

Limnonectes woodworthi (KU 330226) from mid-elevation Mt. Cagua (Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Occidozyga laevis (Günther, 1859)

Occidozyga laevis (Fig. 33) is a common, widespread species known throughout many of the islands and neighboring continental landmasses of Southeast Asia (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330327–52; Location 1b: KU 330353–61, 330717, PNM 5256–63; Location 2: KU 320164–71, 323421; Location 5: USNM 498519; Location 6: USNM 498520–23; Location 15: USNM 498727–19, 499017.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307540–57; Location 23: KU 326478–79; Location 30: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: PNM 5179–86; MVW photo voucher.

Occidozyga laevis (specimens not collected) from Dyadyadin (Location 32). Photo: MVW.

Family Microhylidae

Kaloula kalingensis Taylor 1922

Kaloula kalingensis (Fig. 34) originally was described from Balbalan, Kalinga Province (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: 330264–72; Location 1b: KU 330273–78, PNM 7485–89; Location 11: PNM 7461–63.

Isabela Province—Location 34: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Kaloula kalingensis (KU 330273) from forests below the crater of Mt. Cagua (near Location 1a). Photo: RMB.

Kaloula picta (Duméril and Bibron, 1841)

Kaloula picta (Fig. 35) is a widespread Philippine endemic, distributed widely in low elevation agricultural areas, along riparian habitats in the foothills of mountain systems, and along low-elevation river valleys and coastal areas (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 17; Location 5: USNM 498516–17; Location 6: 498518; Location 11: USNM 498638–48, PNM 6701–07; Location 12: PNM 6708–12; Location 14: USNM 498719; Location 15: USNM 498720.

Kaloula pulchra Gray, 1825

Kaloula pulchra is an invasive species (

Cagayan Province—Location 31: no specimens (ACD field observation).

Isabela Province—Cagayan River banks: no specimens (ACD and RMB field observations).

Kaloula picta (KU 330616) from the forest edge just above Barangay Magrafil (near Location 1b). Photo: RMB.

Kaloula rigida Taylor 1922

Kaloula rigida (Fig. 36) was described from Baguio City, Benguet Province (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330470–74; Location 1b: KU 330475–515; Location 3: PNM 7492; Location 13: PNM 9666–67; Location 15: USNM 498721–16, 498950, 498963–64, 499016.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 326467–70.

Kaloula rigida male (KU 330507) and female (KU 330508) in amplexus, following heavy rains near Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Family Ranidae

Hylarana similis (Günther, 1873)

Hylarana similis (Fig. 37) is ubiquitous throughout Luzon and associated land-bridge islands (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330516–63; Location 1b: KU 330564–84; Location 2: KU 320252–65; Location 12: PNM 8378; Location 13: USNM 498711–15, PNM 8301–05; Location 15: USNM 498758–60, 498972.

Isabela Province—Location 23: 326367–69; Location 30: PNM8371; MVW photo voucher; Location 34: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Hylarana similis (KU 329815) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Sanguirana luzonensis (Boulenger, 1896)

This widespread, Luzon faunal-region (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330393-95; Location 1b: KU 330396–424; Location 13: USNM 498694–703, PNM 8128–37; Location 15: USNM 498737–49, 498951–52, 498965–66, 499020–21; Location 16: USNM 498735.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307636; Location 23: KU 326491; Location 30: PNM 8162–66, MVW photo voucher; Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Sanguirana luzonensis female (KU 330408) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Sanguirana tipanan (Brown, McGuire, and Diesmos, 2000)

The presence of this species (Fig. 39), originally described from Aurora Province (

Isabela Province—Location 30: no specimens (ACD photo voucher).

Sanguirana tipanan (CMNH 5582) photographed in Aurora Province (

Family Rhacophoridae

Philautus surdus (Peters, 1863)

A single specimen of this widespread Luzon-region rhacophorid frog has been collected in Palanan. The loud “crunch…crunch” vocalizations of this species have been heard by the authors at Barangay Nassiping, Municipality of Gattaran.

Cagayan Province—Location 3: no specimens (RMB and ACD field observations).

Isabela Province—Location 30: PNM 5378.

Polypedates leucomystax (Gravenhorst, 1829)

Philippine Polypedates leucomystax (Fig. 40) is a genetically distinct variant of a widespread species complex ranging throughout much of Southeast Asia (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330233; Location 1b: KU 330230–32; Location 3: KU 307624–30; Location 5: USNM 498547–49, 498981–89, PNM 3886–90; Location 6: USNM 498550; Location 7: USNM 498551–53; Location 8: USNM 498554–58; Location 11: USNM 498650–66, PNM 3891–3907; Location 14: USNM 498763; Location 15: USNM 498765–76, 498992–94; Location 17: USNM 498764.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307631–35; Location 22: 307618–23; Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: PNM 3916.

Female Polypedates leucomystax (KU 330233) from the crater of Mt. Cagua, Location 1a. Photo: JS.

Rhacophorus pardalis Günther, 1859

This species of Southeast Asian “flying frog” (Fig. 41) is also known from the islands of Indonesia and Malaysia (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330279–92; Location 1b: KU 330293–99; Location 15: USNM 498777–82, 499023, PNM 5473.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 326492–94; Location 32: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 37: PNM 8607.

Rhacophorus pardalis female (KU 330294) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Rhacophorus appendiculatus (Günther, 1858)

Rhacophorus appendiculatus, although considered widely distributed (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330228–29.

Rhacophorus appendiculatus (KU 330228) from the forest in the crater of Mt. Cagua, near Location 1a. Photo: JS.

Family Agamidae

Bronchocela marmorata Gray, 1845

We collected individuals of this widespread northern Luzon species (Fig. 43) 4–8 m above the ground in secondary growth trees and agricultural hedgerows. Our specimens are clearly diagnosable, in accordance with

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330104–06; Location 2: KU 320283–84; Location 3: PMM 7559; Location 13: USNM 498716; Location 15: USNM 498783; Location 20: PNM 7470.

Male Bronchocela marmorata (KU 330106) from low-elevation, Mt. Cagua (just above Barangay Magrafil), below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Draco spilopterus (Wiegmann, 1834)

This widely distributed Luzon and Visayan faunal-region (

Cagayan Province—Location 2b: KU 330061–62; Location 3: KU 307457–48, 327734, 327736.

Isabela Province—Location 22: KU 327735; Location 25: KU 327737; Location 26: KU 327739; Location 32: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: PNM 1007–08; Location 36: PNM 1011–12.

Male Draco spilopterus (KU 330062) from low-elevation, Mt. Cagua (just above Barangay Magrafil), below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Family Gekkonidae

Cyrtodactylus philippinicus (Steindacher, 1867)

One of the most common squamates in the northern Philippines, Cyrtodactylus philippinicus (Fig. 45) is common from low- to mid-elevation forests, at elevations of 800 or 900 m (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330168–78; Location 1b: KU 330179–97, PNM 1467; Location 20: PNM 1466.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 327071–76; Location 26: 327077–78; Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Cyrtodactylus philippinicus from Palanan (Location 30). Photo: MVW.

Gehyra mutilata (Wiegmann, 1834)

Gehyra mutilata (Fig. 46) is a common, widespread “house” gecko that differs from the other most common human commensals (Hemidactylus platyurus and Hemidactylus frenatus) in that it prefers dark perches, away from overhead lights, probably as a result of competitive interactions with these latter species (

Cagayan Province—Location 3: KU 307471; Location 5: USNM 498559–61, 499244–46, 499249; Location 7: USNM 498562–63, 499247–48, PNM 5367; Location 9: USNM 498601–05; Location 14: USNM 498791; Location 17: USNM 498786–90, 499250.

Isabela Province—Location 36: PNM 6500–01.

Gehyra mutilata (PNM 6501) from Barangay Dibuluan (Location 31). Photo: ACD.

Gekko gecko (Linnaeus, 1758)

Gekko gecko (Fig. 47) is a widespread Southeast Asian species. In the northwrn Sierra Madre, specimens have been observed on a variety of man-made structures in and around human habitation (but this species is less frequently encountered in forests). Although we heard its distinctive vocalizations at many of the sites we visited in Cagayan and Isabela Provinces (including Locations 2–4, 19, 20–22, 28–30), we seldom endeavored to collect this identifiable and well-known species. One specimen, captured on a house in a small village, was brought to us by a resident of Barangay Magrafil.

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330057.

Male Gekko gecko (KU 330057) the outskirts of Barangay Magrafil. Photo: RMB.

Gekkokikuchii (Oshima, 1912)

Gekko kikuchii (Fig. 48) is the name available for the genetically distinct northern Luzon and Lanyu Island (Taiwan) lineage (

Cagayan Province—Location 11: USNM 340413–21, PNM 4114–22; Location 13: USNM 340376–412; Location 15: USNM 499241–42.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307472; Location 25: KU 327390.

Gekko kikuchii (ACD 3077, deposited in PNM) from Barangay Binatug, San Mariano (Location 22). Photo: K. M. Hesed.

Hemidactylus frenatus Duméril & Bibron, 1836

One of the most common “house” geckos (Fig. 49) in the Philippines, this species is frequently encountered under exterior lights of buildings, preying on insects attracted to artificial illumination. It can be easily diagnosed from Hemidactylus platyurus by its round tail and smooth, non-frilled flanks.

Cagayan Province—Location 3: KU 307475–76; Location 5: USNM 498564–78, 499251; Location 7: USNM 498579–90, PNM 5368–70, 5490; Location 8: USNM 498591–600; Location 11: PNM 5444–5459; Location 12: USNM 498669; Location 15: USNM 498953–55, 499257; Location 17: USNM 498792–94, 499258; Location 18: USNM 499252; Location 36: PNM 7039.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307477–87.

Hemidactylus frenatus (specimen in PNM) from Barangay Dibuluan (Location 31). Photo: ACD.

Hemidactylus platyurus (Schneider, 1792)

Like its congener, Hemidactylus frenatus, Hemidactylus platyurus is one of the most common “house” geckos in the Philippines and is frequently encountered under exterior lights of buildings, preying on insects attracted to artificial illumination. It is diagnosable from Hemidactylus frenatus by the presence of expanded dermal flanges along the sides of the body and by its flattened, transversely expanded tail.

Cagayan Province—Location 3: KU 307442–48; Location 5: USNM 499243, 499253–56; Location 11: USNM 498670–84; Location 12: USNM 498667–68, PNM 6118–19; Location 15: USNM 498795–828; Location 17: USNM 498784–85.

Hemidactylus stejnegeri Ota & Hikida, 1989

Diagnosed as a triploid species (

Cagayan Province—Location 15: USNM 291834.

Lepidodactylus cf. lugubris (Duméril & Bibron, 1836)

Although

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330065–66.

Isabela Province—Location 22: KU 327729–30.

Lepidodactylus cf. lugubris (KU 330065) from the forested crater of Mt. Cagua, Location 1a. Photo: JS.

Luperosaurus cf. kubli Brown, Diesmos & Duya, 2007

A single specimen provisionally assigned to the rare species Luperosaurus kubli (

Isabela Province—Location 32: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Luperosaurus cf. kubli (specimen not collected) from Palanan (Location 32). Photo: MVW.

Pseudogekko compressicorpus (Taylor, 1915)

As currently defined, this species is widely distributed throughout the Philippines (Fig. 52), from extreme southwestern Mindanao, throughout the eastern island arc (Leyte–Samar) and the Bicol faunal region (including Polillo and Catanduanes islands), and widely throughout the rest of Luzon (

Cagayan Province—Location 2b: KU 330058; Location 3: PNM 8270.

Pseudogekko compressicorpus (KU 330058) from 850 m on Mt. Cagua, above Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Family Scincidae

Brachymeles bicolor (Gray, 1845)

Brachymeles bicolor (Fig. 53) has remained one of the Philippines most distinctive and enigmatic skinks since the time of its original discovery (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330073–78; Location 111 PNM 1341; Location 13: USNM 498717, PNM 1340; Location 15: USNM 498829–33, 498997, CAS 186111.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 326112–13; 329452–56; Location 24: KU 329458; Location 26: KU 329459; Location 28: KU 329460; Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Brachymeles bicolor (KU 330074) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Brachymeles bonitae Duméril & Bibron, 1839

As currently defined, Brachymeles bonitae (Fig. 54) is a common, widespread species, endemic to the Luzon faunal region (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330094–100; Location 2: KU 320468–70, 330101–03; Location 15: USNM 498835–37; Location 16: USNM 498834.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307436; Location 23: KU 326087, 326091–95, 326561.

Brachymeles bonitae (KU 330100) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Brachymeles kadwa Siler & Brown 2010

This recently described species (Fig. 55) is known from numerous localities across Luzon (Bicol Peninsula, Aurora, Isabela, Laguna, and Cagayan provinces) and also Calayan and Camiguin Norte islands, north of Luzon (

Cagayan Province—Location 3: KU 307437, 326139–66.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 326131–36; Location 24: KU 326124–28; Location 25: KU 326129–30; Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Brachymeles kadwa (specimen not collected) from Location 33. Photo: MVW.

Brachymeles muntingkamay Siler, Rico, Duya & Brown 2009

Recently discovered and described (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330086–89; Location 1b: KU 330090–93; Location 2: KU 327347.

Isabela Province—Nassiping: no specimens (ACD photovoucher)

Brachymeles muntingkamay (KU 330093) from 900 m on Mt. Cagua, above Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Eutropis cumingi (Brown & Alcala 1980)

Eutropis cumingi (Fig. 57) was described in 1980 from several small series of specimens from Subic Bay, southwest Luzon (CAS 15473; holotype, and CAS 15452, 15454–56, and 15472, 60955–64, paratypes), “northern Luzon” (FMNH 161666–68, paratypes), Ifugao (FMNH 177299–300, paratypes), and generally, “Luzon” (exact locality unknown: FMNH 177304–09, 177311, paratypes). Given its wide distribution, we are not surprised to find specimens diagnosable as this species in the northern Sierra Madre. Past studies have also found it present in the Babuyan and Batanes islands to the north, on Lanyu Island near Tawian (

Cagayan Province—Location 15: USNM 498999–9011.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 327365, 327376–82; Location 24: KU 327383, 327386; Location 26: KU 327384–85, 327387–88.

Eutropis cumingi (uncataloged specimen in PNM) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: ACD.

Eutropis multicarinata borealis (Brown & Alcala 1980)

Known from the northern Philippines and Lanyu Island near Taiwan, this species is considered widespread throughout Luzon and associated smaller island groups (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330070; Location 1b: KU 330071–72; Location 11: PNM 5462–66.

Isabela Province—Location 21; PNM 9519, 9566; Location 23: KU 327366–67, 327533; Location 24: PNM 674, 1385–86; Location 26: KU 327533; Location 28: KU 327530–32; Location 36: PNM 6507, 6517.

Eutropis multicarinata borealis (KU 330072) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Eutropis multifasciata (Kuhl, 1820)

This widespread Southeast Asian species (

Cagayan Province—Location 3: KU 307538–39; Location 5: USNM 305883, 498608–09; Location 6: USNM 498606–07; Location 7: USNM 498610–17; Location 11: USNM 498686–91, PNM 669, 1205, 1208, 1267, 1269, 1271, 1291, 1294, 1313; Location 15: USNM 498876–95, 498957; Location 16: USNM 498840–45; Location 17: USNM 498846–75.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 327560–61; Location 22: KU 307537; Location 23: KU 327534–48; Location 24: KU 327548–54; Location 25: KU 327555–59; Location 26: KU 327563–66; Location 28: KU 327567–69.

Eutropis multifasciata (uncataloged specimen in PNM) from Barangay Dibuluan, San Mariano (Location 31). Photo: ACD.

Lamprolepis smaragdina philippinica Mertens, 1829

Lamprolepis smaragdina philippinica (Fig. 60) is one of the most locally abundant lizards in coastal areas throughout the archipelago. Also encountered in agricultural plantations (coconut palm plantations, avocado, cacao, and mango plantations) and in regenerating forest nurseries and riparian corridors, Lamprolepis smaragdina philippinica exhibits geographically based color variation, with fully green individuals at some localities, brown patches on the head and dorsal surfaces or forelimbs at other sites, and all gray-brown individuals at two known areas (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330054; Location 3: KU 307489; Location 11: USNM 498685; Location 12: PNM 5461; Location 15: USNM 498838–39, 498998, PNM 5474; Location 20: PNM 7471.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 326564; Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: PNM 6728.

Lamprolepis smaragdina philippinica (specimen not collected) from Palanan (Location 33). Photo: MVW.

Lipinia cf. vulcania Girard 1857

Girard’s (1857) single specimen of this distinctive species reportedly originated at1700 m asl on Dapitan Peak, Zamboanga Peninsula, of Mindanao Island; this unique specimen is now presumed lost (

Isabela Province—Location 23: ACD 2036, deposited in PNM.

Lipinia cf .vulcania (specimen in PNM) from Barangay Dibuluan, San Mariano (Location 30). Photo: ACD.

Otosaurus cumingi

This is the largest Philippine species in the Sphenomorphus Group (Greer and Parker 1967) and was formerly referred to the genus Otosaurus (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330063–64, 330652, PNM 8484; Location 15: USNM 498904.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 326581–82, PNM 671; Location 31: (specimen in PNM).

Otosaurus cumingi juvenile (KU 330652) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Otosaurus cumingi adult male (PNM 8484) mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: ACD.

Pinoyscincus abdictus aquilonius (Brown & Alcala 1980)

Recently transferred from the paraphyletic genus Sphenomorphus to the newly recognized genus Pinoyscincus (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330198–05; Location 1b: KU 330206–21, 330224; Location 2: KU 320497, 330222–23; Location 15: USNM 498897–903; Location 16: USNM 498896.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307677, 327657–58; Location 22: KU 327664; Location 23: KU 326568–69, 327642, 327643–53; Location 24: KU 327659–63; Location 25: KU 327654–56; Location 30: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Pinoyscincus abdictus aquilonius (KU 330206) low-elevation, Mt. Cagua, below Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Parvoscincus decipiens (Boulenger, 1895)

Recently transferred from the paraphyletic genus Sphenomorphus to an expanded Parvoscincus (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330119–22; Location 1b: KU 330067–69, 330123–30, PNM 8486; Location 3: KU 326718: Location 5; PNM 5371–72; Location 6: USNM 498618–25; Location 13: PNM 8427; Location 15: USNM 498906–12; Location 16: USNM 498905.

Isabela Province—Location 22: KU 326585, 326603, 326715; Location 21: PNM 6544; Location 23: KU 326586, 325592–96, 326706–08; Location 24: KU 326560, 326604–12; Location 25: 326597–602, 326709–12; Location 26: KU 326713–14, 327429; Location 27: 326716–17; Location 30: PNM 6531, 6538, 6541; Location 36: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Parvoscincus cf. decipiens

A second small leaf-litter skink species, related to Parvoscincus decipiens (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330120, 330122, 330126, 330128.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 329951, 330067–68, 330119.

Parvoscincus decipiens (KU 326609) from Barangay Dibuluan, San Mariano (Location 31). Photo: ACD.

Parvoscincus cf. decipiens (KU 330124) from 900 m asl, Mt. Cagua, above Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Parvoscincus leucospilos (Peters, 1872)

Yet another species recently transferred from the paraphyletic genus Sphenomorphus on the basis of an extensive phylogenetic analysis and a survey of morphological characters (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: no specimens (RMB and J. E. Fernandez field observation).

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 320522; Location 24: KU 327785–86; Location 25: KU 327787–96.

Parvoscincus leucospilos (KU 327785) from Barangay Dibuluan, San Mariano (Location 30). Photo: ACD.

Parvoscincus steerei (Stejneger, 1908)

Considered a widespread, variable Philippine endemic, Parvoscincus steerei, like its congener, Parvoscincus leucospilos, has been transferred from the paraphyletic genus Sphenomorphus on the basis of a robust phylogenetic analysis and a survey of new morphological characters (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330107–17; Location 1b: KU 330118; Location 5: PNM 5373–74; Location 6: USNM 498626-29; Location 15: USNM 498914; Location 16: USNM 498913.

Isabela Province—Location 23: PNM 673.

Parvoscincus tagapayo (Brown, McGuire, Ferner & Alcala 1999)

Discovered only in 1999 (

Cagayan Province—Location 2b: KU 330059–60.

Family Varanidae

Varanus marmoratus (Wiegmann, 1834)

This Luzon faunal region (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330729; Location 3: KU 326697; Location 5: USNM 305884; Location 13: PNM 5475; Location 15: USNM 498915–17; Location 19: PNM 5989.

Isabela Province—Location 23: PNM 683.

Varanus marmoratus (KU 330731) from low-elevation, Mt. Cagua, below Location 1b, near Barangay Magrafil. Photo: RMB.

Varanus bitatawa Welton, Siler, Benett, Diesmos, Duya, Dugay, Rico, van Weerd & Brown 2010

This distinctive species of arboreal, frugivorous, large-bodied monitor lizard (Figs 69, 70) was discovered by scientists during the past decade but not described until 2010 (holotype PNM 9719 from Aurora Province); the species was previously well known to Agta tribes peoples (Estioko–Griffin and Griffin 1975;

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330730; Location 2: KU 330636, 330731.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 322188 (paratype); Exact locality unknown: KU 327100.

One of the firstphotographs in life of the newly discovered (

A large (nearly 2 m) adult male Varanus bitatawa in life, near Location 2. Photo: RMB.

Varanus bitatawa (skull and partial specimen salvaged: KU 330636) stew being prepared at Location 2 by Agta tribesmen. Photo: RMB.

Family Pythonidae

Broghammerus reticulatus (Schneider 1801)

Reticulated pythons (Fig. 72) are common in a wide variety of low- to mid-elevation habitats, including residential areas, agricultural plantations, and the slash-and-burn shifting disturbed forests typical of the foothills of major Sierra Madre mountain slopes. Also hunted for meat and leather (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330021; Location 15: USNM 498919, 499259; Location 17: USNM 498918.

Isabela Province—Location 21: PNM 9157.

Subadult maleBroghammerus reticulatus (KU 330021) at Location 1a. Photo: JS.

Family Colubridae

Ahaetulla prasina preocularis (Taylor, 1922)

Widely distributed throughout the Philippines (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330032–33; Location 1b: KU 330034–37; Location 3: KU 307433; Location 15: USNM 498920; Location 16: USNM 498921.

Isabela Province—Location 21: PNM 241; Location 23: KU 327171; Location 26: KU 327172; Location 30: PNM 254; Location 32: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 35: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Ahaetulla prasina preocularis (KU 330037) green morph from Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Ahaetulla prasina preocularis (specimen not collected) yellow morph from Palanan (Location 35). Photo: MVW.

Boiga cynodon (Boie, 1827)

Widely distributed in Southeast Asia (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330586–87; Location 3: KU 327774, 327777.

Isabela Province—Location 24: KU 327773.

Boiga cynodon (KU 330586) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: LJW..

Boiga dendrophila divergens Taylor, 1922

One specimen of this widespread endemic Luzon subspecies (Fig. 76) has been collected at the Municipality of Santa Ana (circumstances of collection unknown). This species is undoubtedly widespread throughout low elevation and coastal habitats of northeastern Luzon, and its presence has been confirmed in the Babuyan Islands off the northeast tip of Luzon as well (

Cagayan Province—Location 12: PNM 969.

Boiga dendrophila divergens (PNM 969) from Santa Ana (Location 12). Photo: ACD.

Boiga philippina (Peters, 1867)

A single specimen was collected in the Nassiping Forest Reserve where it was active at night in lower branches of streamside understory vegetation. Also now known from the Babuyan Islands (

Boiga philippina (KU 307435) from Barangay Nassiping, Gattaran (Location 3). Photo: ACD.

Cagayan Province—Location 3: KU 307435.

Calamaria bitorques Peters 1872

Previously collected in the southern Sierra Madre (Aurora Province;

Calamaria bitorques (KU 327409) from Barangay Dibuluan, San Mariano (Location 31). Photo: ACD.

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: PNM 8475; Location 15: USNM 498922; Location 20: PNM 8273.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 327409–10.

Calamaria gervaisi Duméril & Bibron, 1854

Widely distributed in the Philippines (

Calamaria gervaisi (KU 330084) from 1000, Mt. Cagua, near Location 1a. Photo: RMB.

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330081–85.

Isabela Province—Location 21: KU 307441, PNM 102; Location 23: KU 326693; Location 26: KU 327406–07; Location 30: PNM 126.

Coelognathus erythrurusmanillensis (Jan, 1863)

We encountered this Luzon endemic (

Coelognathus erythrurus manillensis (uncataloged specimen in PNM) from Barangay Binatug (Location 22). Photo: ACD.

Cagayan Province—Location 3: KU 307468; Location 10: USNM 498631–33; Location 19: PNM 388.

Isabela Province—Location 24: uncataloged specimen in PNM; Location 30: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Cyclocorus lineatus lineatus (Reinhardt, 1843)

One of only four snake genera endemic to the Philippines (

Cyclocorus lineatus lineatus (KU 326690) from Barangay Dibuluan, San Mariano (Location 30). Photo: ACD.

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: 330024–27; Location 1b: 330028–29, PNM 8477; Location 2: KU 320511; Location 5: USNM 305879–82; Location 6: USNM 498630; Location 15: USNM 498923–25, 292494; Location 18: USNM 292495.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 326689–90, 327755; Location 24: KU 327756–59; Location 26: KU 327760–61; Location 28: KU 327762–64; Location 34: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Dendrelaphis luzonensis

Luzon populations of Dendrelaphis luzonensis (

Dendrelaphis luzonensis (KU 330030) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330030; Location 5: USNM 498636, 499013, CAS 116192; Location 11: PNM 474; Location 17: USNM 498926; Location 19: PNM 458, 461.

Isabela Province—Location 21: PNM 9146, 9189, 9190.

Dendrelaphis marenae Vogel & van Rooijen, 2008

Common in residential and agricultural areas where they are most often seen active during the day on the ground or sleeping in bushes at night, this common species is widely distributed throughout the northern Philippines (

Dendrelaphis marenae (uncataloged ACD specimen in PNM). Photo: ACD.

Cagayan Province—Location 5: USNM 498637; CA 116193; Location 10; USNM 498634; Location 13: PNM 8410.

Isabela Province—Location 21: PNM 9163; Location 33: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: PNM 542.

Dryophiops philippina Boulenger, 1896

This widespread Philippine endemic (Fig. 84) has been collected in recent years with increasing frequency as workers target the remaining low-elevation and coastal forests of the Philippines. We observed one specimen in ultrabasic forests near the municipality of Palanan.

Dryophiops philippina (specimen not collected) from Pangden (Location 33). Photo: MVW.

Isabela Province—Location 32: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Gonyosoma oxycephalum (Boie, 1827)

This widespread, non-endemic, Southeast Asian rat snake (Fig. 85) has been documented throughout the Philippines in a wide variety of habitats. Our records originated in forested areas at low elevations in Binatug and Palanan.

Gonyosoma oxycephalum (ACD 3091) from Barangay Binatug (Location 22). Photo: K. M. Hesed.

Isabela Province—Location 22: uncataloged specimen deposited in PNM (K. Hesed photo voucher); Location 30: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 32: PNM 2031.

Hologerrhum philippinum Günther, 1858

Seldom encountered, the genus Hologerrhum is one of only four snake genera endemic to the Philippines (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330056, PNM 8480; Location 13: USNM 498718.

Isabela Province—Location 36: PNM 6505.

Hologerrhum philippinum (KU 330056) from 650 m asl, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Closeup of Hologerrhum philippinum (KU 33056) illustrating details of head scalation and color, and vibrant yellow ventral coloration. Photo: RMB.

Lycodon capucinus (Boie, 1827)

Widespread and common throughout the Philippines and Southeast Asia (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: Uncataloged specimen at KU (RMB 15097).

Lycodon capucinus (uncataloged ACD specimen in PNM). Photo: ACD.

Lycodon muelleri Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854

Lycodon muelleri (Fig 89) has been recorded throughout Luzon (

Isabela Province—Location 26: KU 327573; Location 35: no specimens (MVW photo voucher); Location 36: PNM 6592.

Typical appearanceof Lycodon muelleri (PNM 6592) from Barangay Binatug (Location 22). Photo: ACD.

Lycodon solivagus Ota and Ross, 1984

A single specimen of this species was collected close to the type locality (

Cagayan Province—Location 5: USNM 499014, PNM 2046.

Oligodon ancorus (Girard, 1858)

Cagayan Province—Location 15: USNM 498927.

Psammodynastes pulverulentus (Boie, 1827)

This common, widespread species (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330023; Location 1b: KU 330022, PNM 8482; Location 13: PNM 8399.

Isabela Province—Location 30: CAS 15320.

Psammodynastes pulverulentus from Location 1a (KU 330023). Photo: JS.

Pseudorhabdion cf. mcnamarae (

Pseudorhabdion mcnamaraewas originally described from northern Negros (Visayan island group;

Isabela Province—Location 22: KU 327206; Location 23: KU 326694–95; Location 26: KU 327189–205.

Pseudorhabdion cf. mcnamarae (KU 327193) from Barangay Binatug (Location 22). Photo: ACD.

Pseudorhabdion cf. talonuran Brown, Leviton & Sison, 1999

Another specimen of a distinctive species of Pseudorhabion has been collected in the Dibanti River basin, Barangay Dibuluan (Municipality of San Mariano). This specimen most closely resembles Pseudorhabdion talonuran, a high-elevation species from Panay Island (

Isabela Province—Location 26: KU 327216.

Ptyas luzonensis (Günther, 1873)

Now considered common and widespread throughout the Luzon and Visayan faunal regions (

Cagayan Province—Location 15: USNM 498931.

Ptyas luzonensis (uncataloged specimen in PNM) from Barangay Dibuluan, San Mariano (Location 31). Photo: ACD.

Rhabdophis spilogaster (Boie, 1827)

Rhabdophis spilogaster (Fig. 93) is diurnally active in riparian habitats at low- to mid-elevations throughout Luzon. Specimens were collected in artificial fish ponds in residential areas, swimming in side pools of small streams, along the borders of flooded rice fields, and among rocks on stream banks in regenerating secondary growth forest.

Cagayan Province—Location 5: USNM 498635; Location 12: PNM 4094; Location 13: PNM 4093; Location 15: USNM 498928–30.

Isabela Province—Location 21: PNM 4106; Location 23: KU 327287–89, PNM 4060; Location 26: KU 327290–94.

Rhabdophis spilogaster (KU 327287) from Barangay Dibuluan, San Mariano (Location 23). Photo: K. M. Hesed.

Tropidonophis dendrophiops (Günther, 1883)

This moderately common natricine snake (Fig. 94) is an ecological generalist that is frequently encountered in riparian habitats (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330031, PNM 8481.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 327620–21.

Tropidonophis dendrophiops (KU 330031) from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Family Elapidae

Hemibungarus calligastercalligaster (Wiegmann, 1835)

A single specimen of this widespread coral snake (

Isabela Province—Location 21: PNM 6607.

Hemibungarus calligaster calligaster (uncataloged ACD specimen in PNM). Photo: ACD.

Naja philippinensis Taylor 1922

A single specimen of the distinctive Philippine cobra (

Cagayan Province—Location 10: USNM292493.

Ophiophagus hannah (Cantor 1936)

Residents of San Mariano and Palanan related to us numerous instances of sightings and resident killings of very large, light tan-colored cobras in the vicinity of settlements and agricultural areas. This species has been reported widely on Luzon (

Isabela Province—Locations 22 and 29: no specimens (ACD field identification).

Family Homalopsidae

Cerberus schneideri (Schlegel, 1837)

Dog-faced water snakes (Fig. 96) are distributed in coastal areas throughout much of Southeast Asia (

Cagayan Province—Location 12: PNM 7544.

Cerberus schneideri (uncataloged ACD specimen in PNM). Photo: ACD.

Family Lamprophiidae

Oxyrhabdium leporinum leporinum (Günther, 1858)

Adults of this common Luzon faunal region endemic (Fig. 97) are frequently encountered actively foraging along stream banks in forests of varying levels of disturbance (

Cagayan Province—Location 1b: KU 330079–80.

Oxyrhabdium leporinum leporinum(KU 330079)from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Family Typhlopidae

Ramphotyphlops braminus (Daudin, 1803)

Specimens of this common, parthenogenetic, presumably introduced species were collected under rocks, palm fronds, and other debris on the edge of forests, and within selectively logged forests at low- to mid-elevations.

Cagayan Province—Location 15: USNM 498933–48, PNM 5476–80; Location 16: USNM 498932.

Isabela Province—Location 24: KU 326636, 326639; Location 25: KU 326640.

Typhlops ruficaudus (Gray, 1845)

A single specimen of this species was collected in a fern axil in a small primary growth forest fragment. As the taxonomy of Philippine typhlopids has improved in the past decade (

Isabela Province—Location 28: KU 328598.

Typhlops sp. 1

This distinctive, probable new species appears related to the Typhlops ruficaudus Group (

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 328594.

Typhlops sp. 2

This distinctive, probable new species appears phenotypically most similar to Typhlops luzonensis, but differs from that species on the basis of several characters of scalation and body size.

Cagayan Province—Location3: KU 328597.

Family Viperidae

Trimeresurus flavomaculatus (Gray, 1842)

Exceedingly common on the lower slopes of Mt. Cagua, Typhlops flavomaculatus (Fig. 98) was observed in high densities surrounding ephemeral pools during the start of the rainy season at mid-elevations (400–700 m). We encountered multiple individuals per night at the same temporary pond as they actively hunted frogs (Occidozyga laevis, Polypedates leucomystax, Rhacophorus pardalis, Kaloula rigida and Kaloula picta) in the lower strata (30–100 cm above the forest floor) of shrub layer vegetation or in temporary pools along muddy paths in secondary forest. Trimereserus flavomaculatus is widespread and common throughout the Luzon faunal region (

Cagayan Province—Location 1a: KU 330038–41; Location 1b: KU 330042–53.

Isabela Province—Location 23: KU 327223–24; Location 26: KU 327225–27; Location 32: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Trimeresurus flavomaculatus (KU 330049)from mid-elevation, Mt. Cagua, Location 1b. Photo: RMB.

Tropidolaemus subannulatus (Gray, 1842)

This common and widespread Luzon and Visayan region pit viper is frequently encountered in forested areas from sea level to mid-montane elevations. Although no specimens are available, it has been photographed in the Dibanti River area, Municipality of San Mariano.

Isabela Province—Location 26: no specimens (ACD photo voucher).

Family Geoemydidae

Cuora amboinensisamboinensis (Daudin, 1802)

Cagayan Province—Location 15: USNM 498949, 499260–61; Location 19: uncataloged specimen in PNM.

Isabela Province—Location 21: PNM 6730; Location 29: PNM 658; Location 30: PNM 6499.

Cuora amboinensis amboinensis (ACD 3229, deposited in PNM) from Barangay Binatug (Location 22). Photo: K. M. Hesed.

Family Trionychidae

Pelochelys cantorii Gray, 1864

Cagayan Province—Location 3: ACD field observation (June, 2006; no specimen); “Upper Cagayan River Basin:” PNM 8487; Location 31: no specimens (ACD field observation).

Isabela Province—Location 24 and St. Victoria: no specimens (MVW photo voucher).

Pelochelys cantorii from the vicinity of San Mariano (specimen not collected); Photo: MVW.

Pelochelys cantorii from the vicinity of St Victoria (specimen not collected); Photo: MVW.

Family Cheloniidae

Caretta caretta (Linnaaeus, 1758)

Loggerhead Turtles have been observed in coastal waters of Isabela Province (van

Chelonia mydas (Linnaaeus, 1758)

Green Turtles have been observed nesting on the beaches of the coast of Isabela Province (MVW, personal observations); we expect the vast, undeveloped coastline of Cagayan Province also supports nesting populations to the north.

Isabela Province—Location 30: no specimens (MVW, personal observations).

Eretmochelys imbricata (Linnaeus, 1766)

Hawksbill Turtles nest on the beaches of the coast of Isabela Province (MVW, personal observations) and we expect this species also nests along the beaches of Cagayan Province to the north.

Isabela Province—Location 30: no specimens (MVW, personal observations).

Family Crocodylidae

Crocodylus mindorensis Schmidt, 1935

The target of an extensive local conservation program (

Cagayan Province—Location: “Northern Cagayan Valley:” USNM 252669, 252699, 252670.

Isabela Province—Locations 23, 28, 34, 36, Divilacan, Benito Soliven and San Guillermo: No specimens (MVW personal observations and photo vouchers).

Crocodylus mindorensis basking on a rock in the Disulap River, Barangay Disulap (Location 29): Photo MVW.

Crocodylus mindorensis basking on a log in the Dunoy Lake, Barangay Dibuluan (Location 24): Photo MVW.

Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801

The large-bodied saltwater crocodile Crocodylus porosus is distributed in estuarine and coastal areas, swamps and rivers, from India, throughout Southeast Asia, eastward to Australia (

Isabela Province—Locations 34, 36: No specimens (MVW personal observations and photo vouchers).

Crocodylus porosus foraging in surf at Maconacon, March 2004. Photo MVW.

Recent studies focusing on the major subcenters of herpetological endemism of the Luzon faunal region (

This study further supports our general expectation of within-Luzon biogeographic provincialism in the sense that the northern Sierra Madre, like the other major components of Luzon, contains a high percentage of locally endemic amphibians and reptiles. At the same time, this study confirms recent and unexpected findings of a considerable degree of overlap in faunal elements between the northern Cordilleras and the northern Sierra Madre (

In this study we have made a preliminary, first-pass, enumeration of the amphibians and reptiles of the northern Sierra Madre and documented species diversity of this region at more than 100 species. This level of diversity surpasses all but one faunistic study for Luzon (

In a 10-day preliminary survey at Aurora National Park,

We concentrate on these two pairs of studies because they are the only two of their kind for Luzon: the northern Cordillera surveys (

A second major lesson involves the naturally patchy distribution of many amphibian and reptile species (

With these caveats in mind, diversity patterns for the reasonably well surveyed areas of Luzon include 52–55 species for the Northern Cordillera (

At present the Luzon faunal region’s herpetological diversity stands at more than 150 species. A total of 49 total amphibian species have been documented, 44 of which are native (5 introduced;

In addition to this expected increase in biodiversity associated with refined taxonomic partitioning (e.g., splitting) of species groups, the northern Philippines has been the focus of the majority of de novo new species discovery in recent decades (W.

The results of this and related studies from the northern Philippines contribute to an ongoing revision of the biogeographic characterization of the Philippines as a “fringing archipelago” with a depauperate fauna in its northern regions (

Conservation of Luzon’s vertebrate biodiversity—in particular the more spectacular Philippine evolutionary radiations and complex ecological communities supported by the remaining forested areas of Luzon—remains an on-going effort, challenged by rapid development, large-scale extractive logging and mining industries and conversion of natural habitats into agricultural lands driven by a burgeoning human population (

We thank the Philippine Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR-Manila), in particular the Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau (PAWB-Manila) for their steadfast support of our research program in the Philippines. We are grateful to Dr. R. Antolin of the DENR-Region 2 Office and the members of the Protected Area Management Board of the Baua and Wangag Watershed Forest Reserves for their support of our field surveys. Fieldwork followed research protocols of the University of Kansas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (KU IACUC) and administrative procedures established in a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between the University of Kansas and PAWB, as outlined in a Gratuitous Permit to Collect (GP) biological specimens, No. 201, administered by PAWB for 2010–2011. At PAWB we thank T. M. Lim, A. Manila, J. de Leon, C. Custodio, and A. Tagtag for their continued support of our work. We are grateful to the people of Gonzaga, Cagayan Province, for their hospitality and participation in our surveys of Mt. Cagua. In particular we thank Gonzaga Mayor Carlito Pentecostes Jr. and Barangay Magrafil Captain Judy Mirasol for their hospitality during our stay in Gonzaga. ACD thanks the Municipal authorities at San Mariano, Baggao, Santa Ana, and Gattaran for support of his field surveys. Recent survey work on Mt. Cagua was made possible by a U.S. National Science Foundation Biotic Surveys and Inventories grant (DEB 0743491) to RMB. Fieldwork in Isabela was made possible by a Rufford Foundation grant (to ACD) and funding from Isabela State University, the Cagayan Valley Program on Environment and Development (CVPED), Leiden University, and the Mabuwaya Foundation (to MVW, DR, and EJ). ACD thanks the Turtle Survival Alliance, National Museum of the Philippines, Conservation International Philippines, University of Santo Tomas, and the National University of Singapore for generously providing additional funding. Logistical assistance in Isabela Province was provided by the PAMB of the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, by the Protected Area Superintendant Unit (notably by W. Savella and F. Mansibang), by the Isabela DENR PENRO and CENRO staff and by the municipal governments of Maconacon, Divilacan, Palanan and San Mariano. We thank S. Rogers (Carnegie Museum), A. Resetar (Field Museum of Natural History), J. Rosado (Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University), J. Vindum (California Academy of Sciences), R. Crombie, and A. Wynn (Smithsonian Institution) for access to data and specimens. For the use of photographic images or provision of other data and information, we thank K. Hesed, J. van Beijnen, J. Guerrero, S. Telan, J. van der Ploeg and P. Brakels. Publication of this work was made possible with support from the One-University Open Access Fund at KU. Particular thanks are extended to our field collaborators J. Fernandez, P. Buenavente, K. Hesed, J. Bulalacao, W. Bulalacao, P. Brakels, J. Cantil, B. Tarun, D. Afan, P. Agustin, M. Babon, A. Diesmos, H. Garcia, J. Holopainen, R. Lagat, E. Mannag, M. Mannag, A. Marcelino, L. Medecilo, M. Quilala, A. Sañosa, R. Sison, G. Tubay, A. Uy, R. Vinuya, N. Antoque, and V. Yngente, who made this work possible with tireless efforts in the field.