(C) 2013 Christopher K. Taylor. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Taylor CK (2013) Further revision of the genus Megalopsalis (Opiliones, Neopilionidae), with the description of seven new species. ZooKeys 328: 59–117. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.328.5439

The Australian harvestmen genus Megalopsalis (Neopilionidae: Enantiobuninae) is recognised as a senior synonym of the genera Spinicrus and Hypomegalopsalis, and seven new species are described in Megalopsalis: M. suffugiens, M. walpolensis, M. caeruleomontium, M. atrocidiana, M. coronata, M. puerilis and M. sublucens. A morphological phylogenetic analysis of the Enantiobuninae is also conducted including the new species. Monophyly of Neopilionidae and Enantiobuninae including ‘Monoscutidae’ is corroborated, with the Australasian taxa as a possible sister clade to the South American Thrasychirus.

Taxonomy, harvestmen, Australasia

The Enantiobuninae (previously Monoscutidae–see

Despite the small number of included species, Spinicrus was a morphologically heterogeneous assemblage right from its initial establishment (

Specimens came from the collections of the Australian Museum, Sydney (AMS), Museum Victoria, Melbourne (MV), Queensland Museum, Brisbane (QM) and Western Australian Museum, Perth (WAM). Specimens were examined using a Leica MZ6 microscope, and drawings were made using a camera lucida. Photographs and measurements were taken using a Nikon SMZ1500 stereo microscope and the NIS-Elements D 4.00.03 programme, and a Leica DM2500 compound microscope. Genitalia were retained in a microvial with the original specimen. Colouration described is as preserved in alcohol. Specimens to be photographed by SEM were dried using hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) as described by

Measurements were taken using a reticle. The number of specimens measured is given as “N = x” at the beginning of each description. Measurements are reported as the mean in millimetres, with total recorded range in parentheses; if no range is given, no variation was recorded. For those species in which not all available specimens were measured, the individuals measured are indicated as such in the specimen listings.

For those species in which discrete male morphs can be identified, separate descriptions are given for each form. The larger and smaller morphs are here referred to as ‘major’ and ‘minor’ males, respectively. Other sources dealing with dimorphic males have referred to the smaller morph as ‘effeminate’ (e.g.

Thrasychiroides brasilicus Soares & Soares, 1947 has had to be omitted from the following key, as it has not been redescribed since its original description (

| 1 | Legs relatively short, femur I less than twice length of prosoma; dorsum of opisthosoma usually conspicuously ornamented | 2 |

| – | Legs long, femur I more than twice length of prosoma | 5 |

| 2 | Bristle groups on right side of shaft-glans junction only; stylus conspicuously inflated (eastern Australia) | Australiscutum |

| – | Bristle groups on both sides of shaft-glans junction; stylus not inflated (New Zealand) | 3 |

| 3 | Opisthosoma with large flanking spines on lateral margins of dorsum | Acihasta salebrosa |

| – | Opisthosoma without such large spines | 4 |

| 4 | Dorsal denticles complex, laterally extended with raised lateral lobes; chelicerae small, unarmed | Monoscutum titirangiense |

| – | Dorsal denticles simple, subcircular; chelicerae with second segment swollen, heavily denticulate | Templar incongruens |

| 5 | Mobile hinge present between leg basitarsus and distitarsus; individual spines as lateral processes on penis (South America) | Thrasychirus |

| – | Junction between basitarsus and distitarsus fused, not hinged; bristle groups as lateral processes on penis (Australasia) | 6 |

| 6 | Pedipalp patella with distinct elongate (longer than broad) prodistal apophysis | 7 |

| – | Apophysis on pedipalp patella absent or, if present, not distinctly longer than broad | 9 |

| 7 | Pedipalp patella apophysis much longer than main body of patella (North Island, New Zealand) | ‘Megalopsalis’ triascuta |

| – | Pedipalp patella apophysis shorter than main body of patella (Australia) | 8 |

| 8 | Chelicerae with distinct frontodistal bulge; glans significantly longer than wide, bent distinctly dorsad from shaft, with vertical platelike lateral process on left side of shaft-glans junction (Western Australia) | Tercentenarium linnaei |

| – | Chelicerae without frontodistal bulge; glans not longer than wide, subtriangular in dorsal view, not bent significantly dorsad from shaft, no platelike lateral process | Megalopsalis (in part) |

| 9 | Glans in lateral view distinctly short and very deep, about as deep as long (New Zealand) | Mangatangi parvum |

| – | Glans elongate or, if relatively short, then distinctly less deep than long | 10 |

| 10 | Pedipalpal claw with ventral tooth-comb; prolateral margin of pedipalpal patella not hypersetose, lacking apophysis (Australia) | 11 |

| – | Pedipalpal claw usually without a tooth-comb; if ventral teeth present, then prolateral margin of pedipalp patella densely hypersetose or with small distal apophysis (New Zealand) | 12 |

| 11 | Dorsum of prosoma often raised in humps; proventral row of hypertrophied spines along femur I; glans in ventral view elongate, more than twice as long as wide, oval or oblong (New South Wales, Queensland) | Neopantopsalis |

| – | Dorsum of prosoma never raised in humps; glans in ventral view less than twice as long as wide, more or less subtriangular | Megalopsalis (in part) |

| 12 | Patella of pedipalp prolaterally densely hypersetose, entirely without apophysis; coxa of pedipalp unarmed | Pantopsalis |

| – | Patella of pedipalp not prolaterally hypersetose, often with small triangular prodistal apophysis; coxa of pedipalp with array of blunt tubercles on median side | Forsteropsalis |

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis

Macropsalis serritarsus Sørensen, 1886 by monotypy.

Megalopsalis serritarsus-species group: Megalopsalis epizephyros Taylor, 2011, Megalopsalis eremiotis Taylor, 2011, Megalopsalis hoggi Pocock, 1903, Megalopsalis pilliga Taylor, 2011.

Megalopsalis leptekes-species group: Megalopsalis leptekes, 2011, Megalopsalis tanisphyros (Taylor, 2011), comb. n. (=Hypomegalopsalis tanisphyros).

Megalopsalis minima-species group: Megalopsalis minima (Kauri, 1954), comb. n. (=Spinicrus minimum), Megalopsalis porongorupensis (Kauri, 1954), comb. n. (=Spinicrus porongorupense), Megalopsalis suffugiens sp. n., Megalopsalis walpolensis sp. n..

Species not placed in species groups: Megalopsalis atrocidiana sp. n., Megalopsalis caeruleomontium sp. n., Megalopsalis coronata sp. n., Megalopsalis puerilis sp. n., Megalopsalis stewarti (Forster, 1949), comb. n. (=Spinicrus stewarti), Megalopsalis sublucens sp. n., Megalopsalis tasmanica (Hogg, 1910), comb. n. (=Pantopsalis tasmanica), Megalopsalis thryptica (Hickman, 1957), comb. n. (=Spinicrus thrypticum).

Megalopsalis can be distinguished from all other genera of Enantiobuninae by its male genital morphology, with the glans being relatively short, broad, distally flattened, and more or less subtriangular in ventral view (e.g. Fig. 3d). It can be further distinguished from Monoscutum, Acihasta, Templar and Australiscutum by having the legs relatively long and thin, and the dorsum of the opisthosoma weakly sclerotised and unarmed (except Megalopsalis atrocidiana;

Ozopores usually large, oblong (small, round in Megalopsalis nigricans). Dorsum of opisthosoma unarmed (except with transverse rows of spines in Megalopsalis atrocidiana). Chelicera segment II denticulate or not; mobile finger usually closing tightly against finger of segment II, fingers bowed apart in larger males of Megalopsalis caeruleomontium. Pedipalp usually with patella shorter than tibia (slightly longer in Megalopsalis nigricans); apophysis present or absent on patella; claw with ventral tooth-row. Glans relatively short, broad, more or less subtriangular in ventral view, proximal section usually somewhat inflated dorsally (except in Megalopsalis nigricans); distal section more or less dorsoventrally flattened. Spiracle with reticulate or partially reticulate covering spines (reduced or absent in Megalopsalis minima-species group); lace tubercles present or absent.

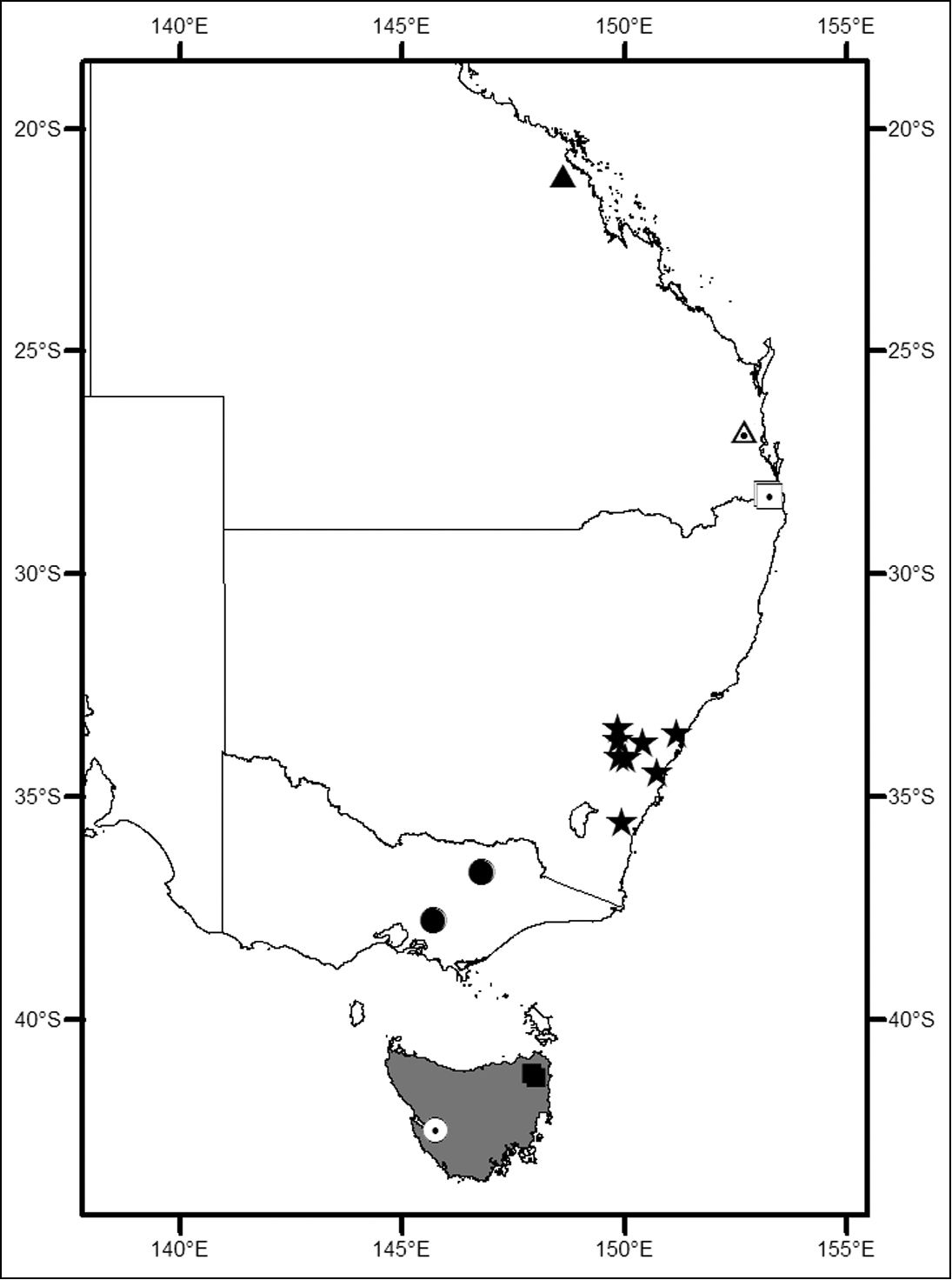

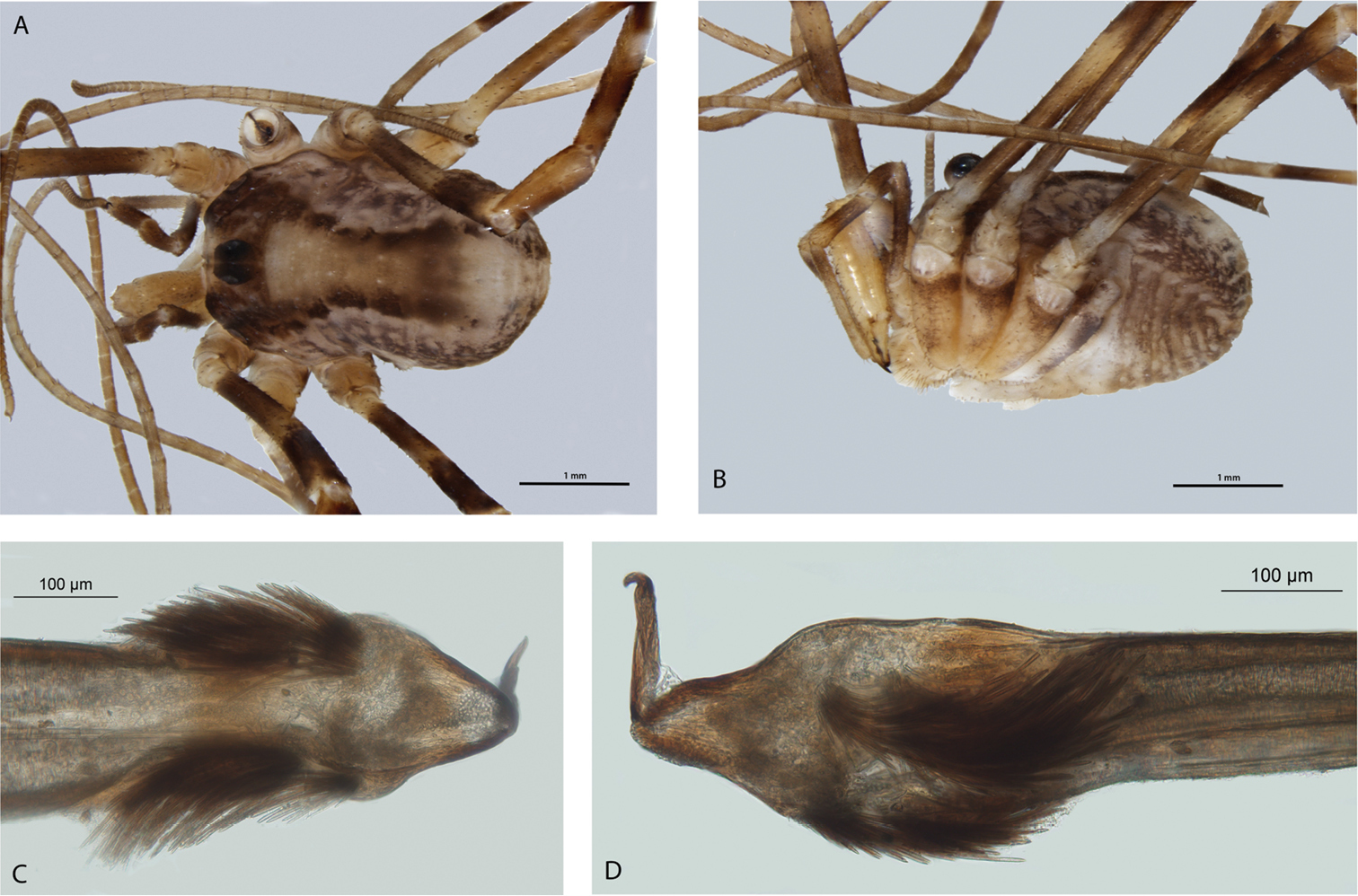

(Figs 1, 7). Southern and eastern Australia.

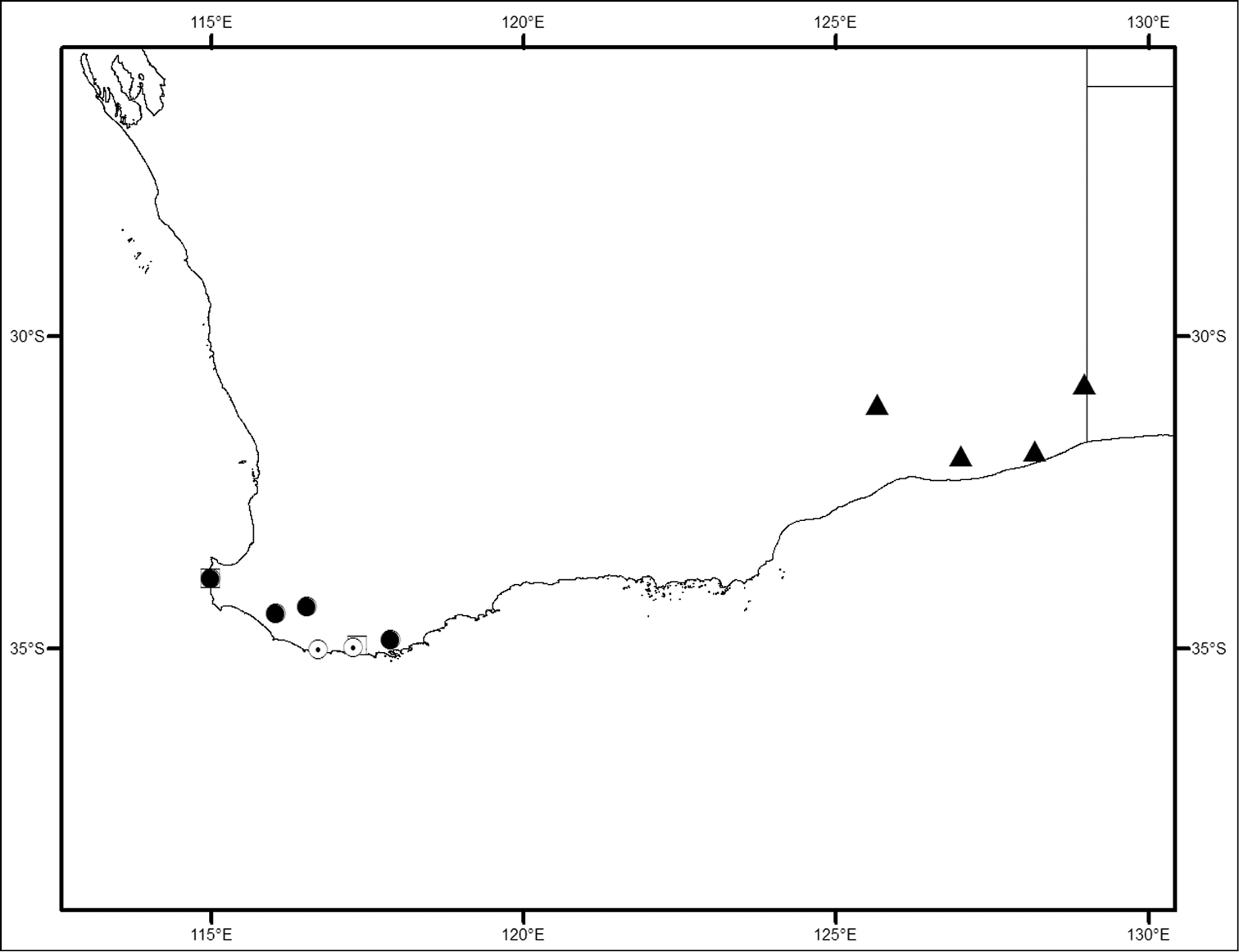

Locality map for Megalopsalis minima species-group in southern Western Australia: open square = Megalopsalis minima; solid circle = Megalopsalis porongorupensis; circle with dot = Megalopsalis walpolensis; solid triangle = Megalopsalis suffugiens.

The genus Spinicrus as previously defined (

Megalopsalis tasmanica and Megalopsalis thryptica were described in detail by

| 1 | Patella of pedipalp with elongate prodistal apophysis | 2 |

| – | Patella of pedipalp without apophysis | 8 |

| 2 | Distitarsi III and IV inflated proximally, with ventral rows of brush-like bristles | 3 |

| – | Distitarsi III and IV not inflated proximally, without ventral brush-like bristles | 7 |

| 3 | Distitarsus II with ventral swellings on pseudosegments | 4 |

| – | Distitarsus II with pseudosegments cylindrical | Megalopsalis hoggi |

| 4 | Femur II with ventral spines | 5 |

| – | Femur II unarmed | Megalopsalis pilliga |

| 5 | Pedipalpal femur with dorsal spines | Megalopsalis epizephyros |

| – | Pedipalpal femur unarmed or with ventral spines only | 6 |

| 6 | Spiracle spines relatively robust, lace tubercles short and forming more extensive field; pedipalpal femur never spinose (New South Wales) | Megalopsalis serritarsus |

| – | Spiracle spines more slender, lace tubercles more elongate but less extensive; pedipalpal femur may have ventral spines (Victoria, South Australia) | Megalopsalis eremiotis |

| 7 | Pedipalpal femur with dorsal and ventral spine rows | Megalopsalis leptekes |

| – | Pedipalpal femur unarmed | Megalopsalis tanisphyros |

| 8 | Dorsum of opisthosoma with transverse rows of spines raised on mounds | Megalopsalis atrocidiana |

| – | Dorsum of opisthosoma unarmed | 9 |

| 9 | Ozopore openings very small, circular, not raised on lateral lobes; pedipalpal femur relatively long, more than 1.5× length of prosoma | Megalopsalis nigricans |

| – | Ozopore openings oblong, raised on lateral lobes; pedipalpal femur shorter than or subequal to prosoma | 10 |

| 10 | Mobile finger of chelicera with ring of setae near central tooth | Megalopsalis caeruleomontium |

| – | Mobile finger of chelicera without setae | 11 |

| 11 | Distitarsi III and IV with ventral rows of brush-like bristles | 12 |

| – | Distitarsi III and IV without ventral brush-like bristles | 15 |

| 12 | Opisthosoma distinctly elongate, about 1.5× as long as wide | Megalopsalis tasmanica |

| – | Opisthosoma not elongate, not much longer than wide | 13 |

| 13 | Dorsum of prosoma entirely unarmed | Megalopsalis sublucens |

| – | Dorsum of prosoma strongly denticulate | 14 |

| 14 | Distitarsus IV inflated proximally | Megalopsalis thryptica |

| – | Distitarsus IV evenly cylindrical | Megalopsalis stewarti |

| 15 | Segment II of chelicera denticulate; spiracle with covering spines absent (Western Australia) | 16 |

| – | Segment II of chelicera unarmed; covering spines present over spiracle (eastern Australia) | 19 |

| 16 | Dorsum of prosoma strongly denticulate | Megalopsalis minima |

| – | Dorsum of prosoma unarmed or with very few denticles | 17 |

| 17 | Legs unarmed or with sparse, relatively long and slender spines; body silvery | Megalopsalis suffugiens |

| – | Legs with numerous small denticles; opisthosoma with dark transverse stripes | 18 |

| 18 | Pedipalp with numerous denticles on femur and patella | Megalopsalis porongorupensis |

| – | Pedipalp unarmed | Megalopsalis walpolensis |

| 19 | Ocularium spinose | Megalopsalis coronata |

| – | Ocularium unarmed | Megalopsalis puerilis |

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_minima

Fig. 31 minor male, Denmark, Western Australia, 34°57'S, 117°21'E, 11 November 1990, A. F. Longbottom, under granite (WAM T72865); 3 minor males, Glenbourne farm, Old Ellensbrook Rd, S of Gracetown, Western Australia, 33°53'S, 115°00'E, 27–28 October 1996, L. Marsh et al., pitfall (WAM T72171, T72184 [2 measured]); 3 major males, ditto, 28–30 June 1997, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfalls, base of cliff (WAM T72167–9; measured); 2 minor males, ditto, 13–15 September 1997, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72176 [measured], T72186); 1 minor male, ditto, 27–29 December 1997, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfalls, site 3 (WAM T72160); 1 minor male, 33°54'28"S, 115°00'49"E, 24–26 October 1998, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72172; measured); 2 minor males, ditto, 33°54'32"S, 115°00'24"E, 24–26 October 1998, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72158); 2 minor males, ditto, 33°54'40"S, 115°00'34"E, 30 October–1 November 1999, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72144; 1 measured); 1 minor male, ditto, 20–22 October 2001, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72193; measured); 1 minor male, ditto, 33°55'08"S, 115°00'44"E, 20–23 October 2000, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72187; measured).

Megalopsalis minima can be distinguished from other members of the Megalopsalis minima-species group by the heavier denticulation on the dorsal prosomal plate (Fig. 3a); the major males can also be distinguished from other species by the proportionately much longer chelicerae (Fig. 3b). It can be distinguished from Megalopsalis porongorupensis by the absence of spines on the pedipalpal femur and patella, and from Megalopsalis suffugiens by the heavily denticulate leg femora (Fig. 3b).

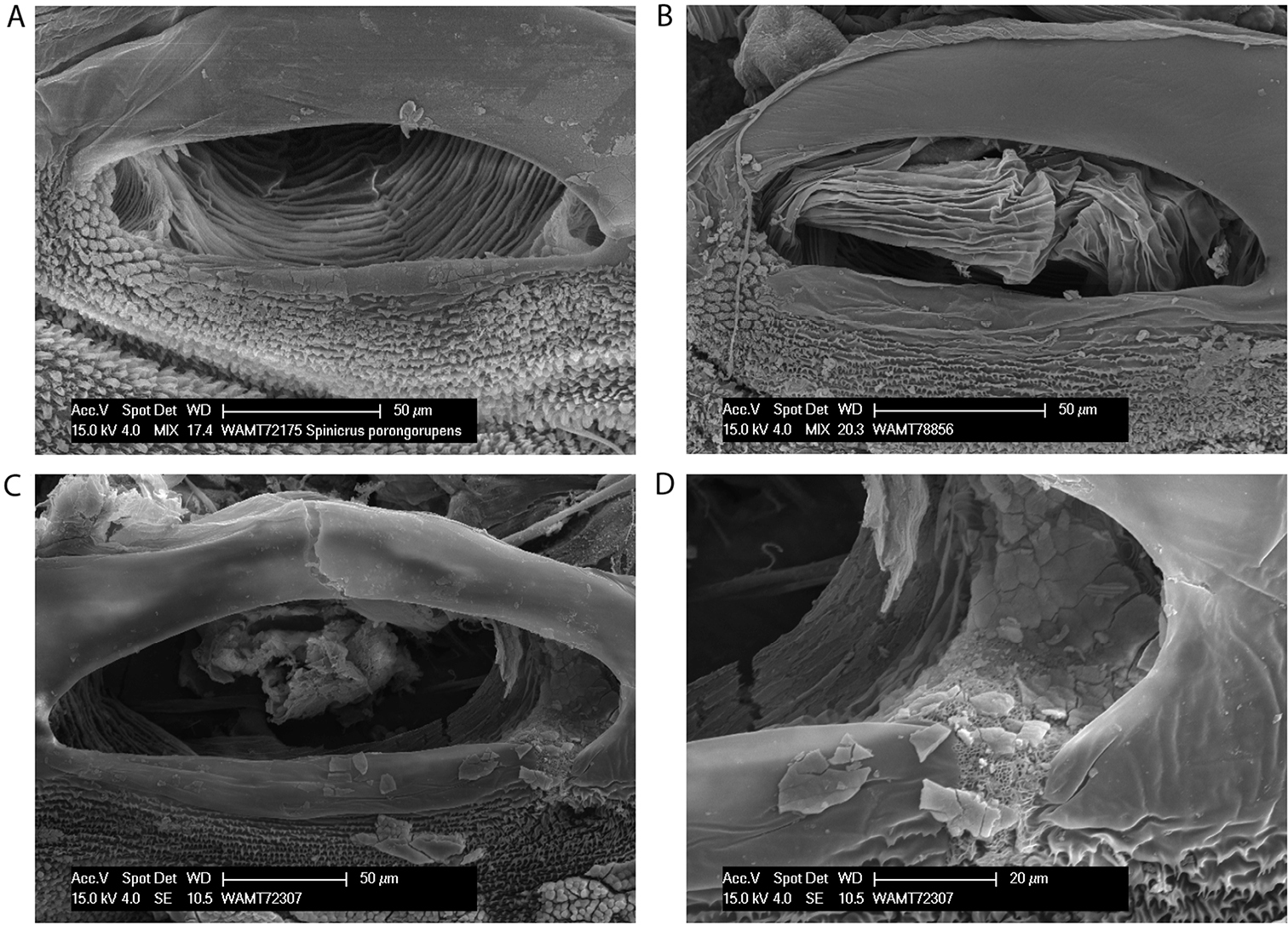

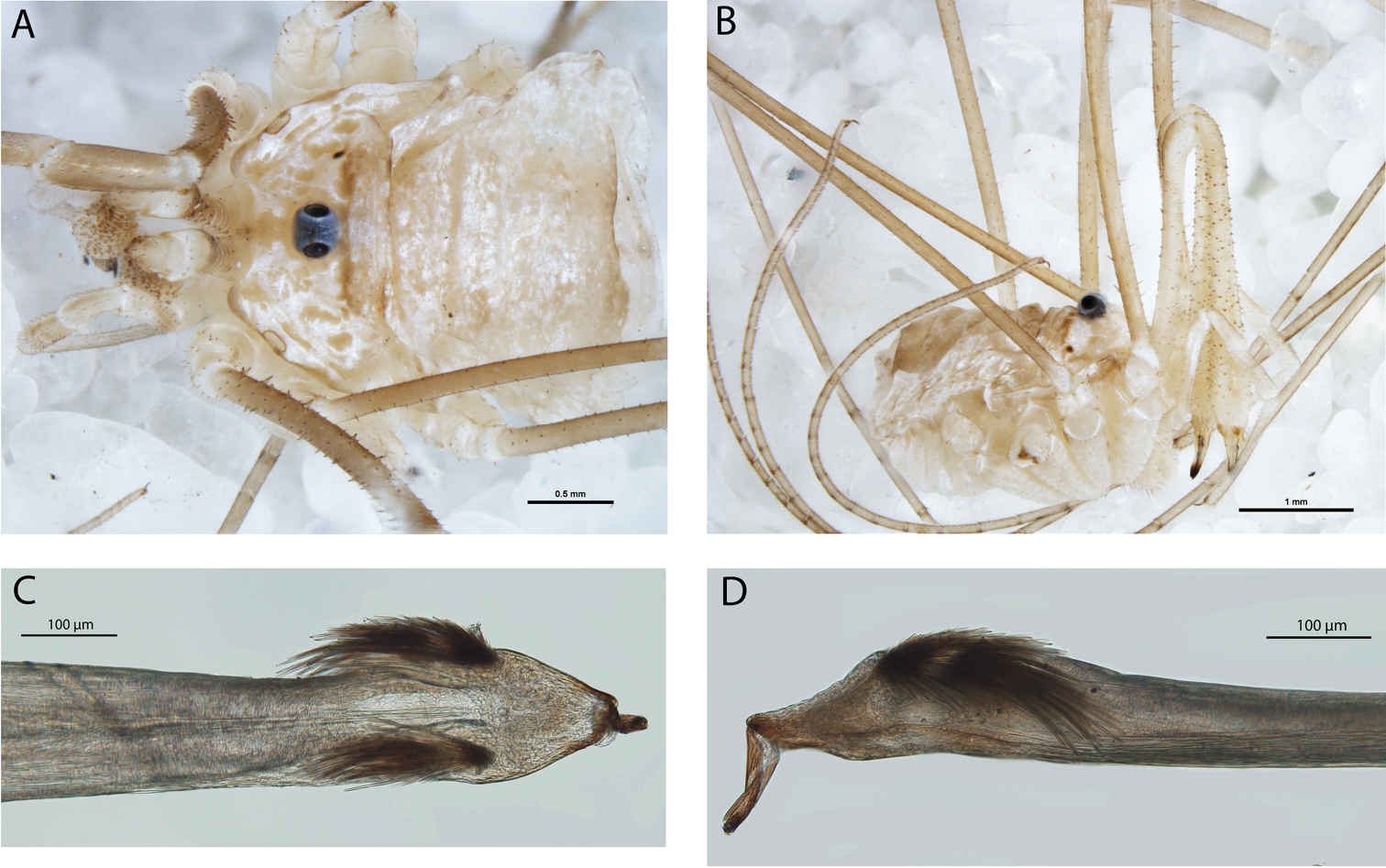

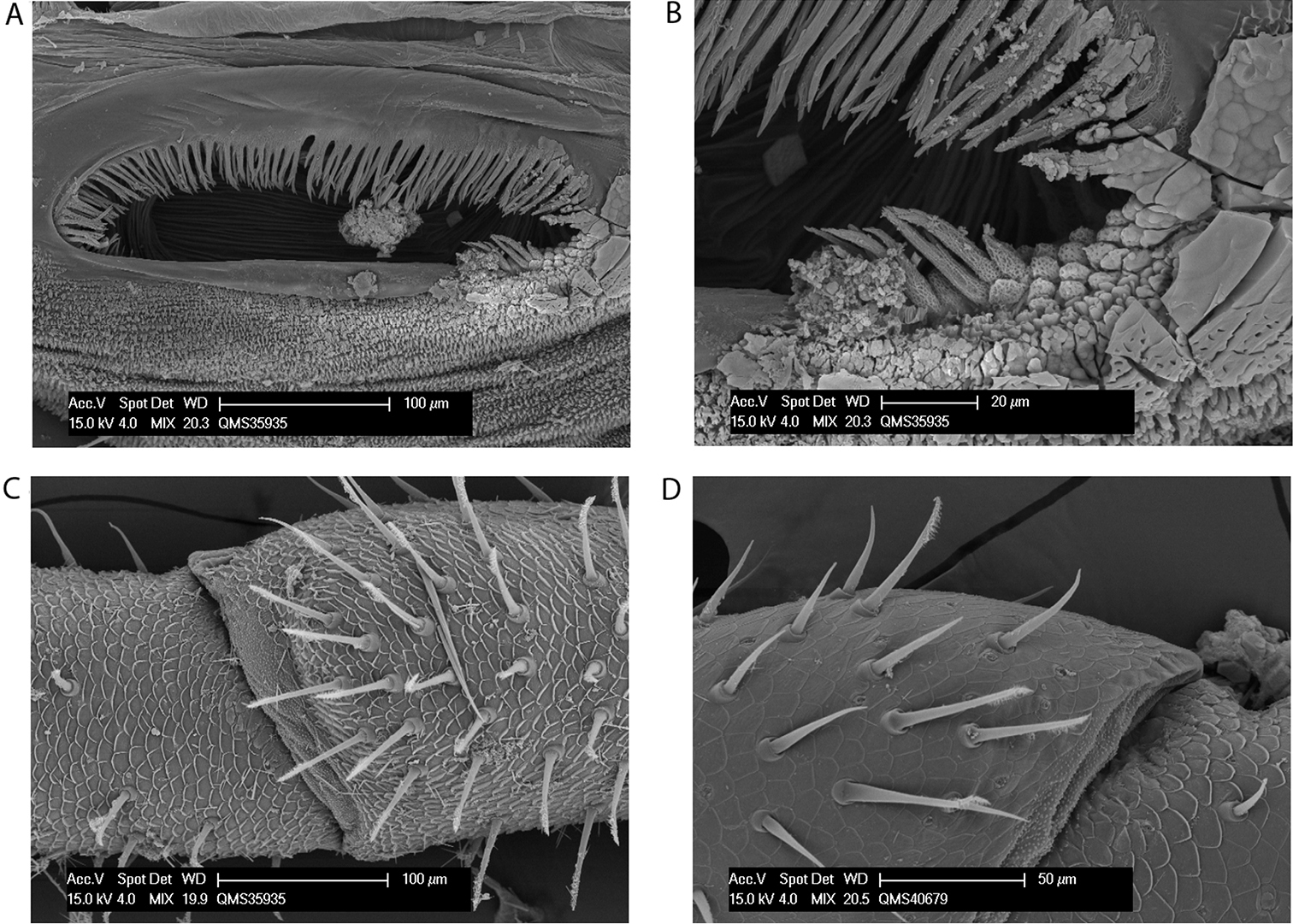

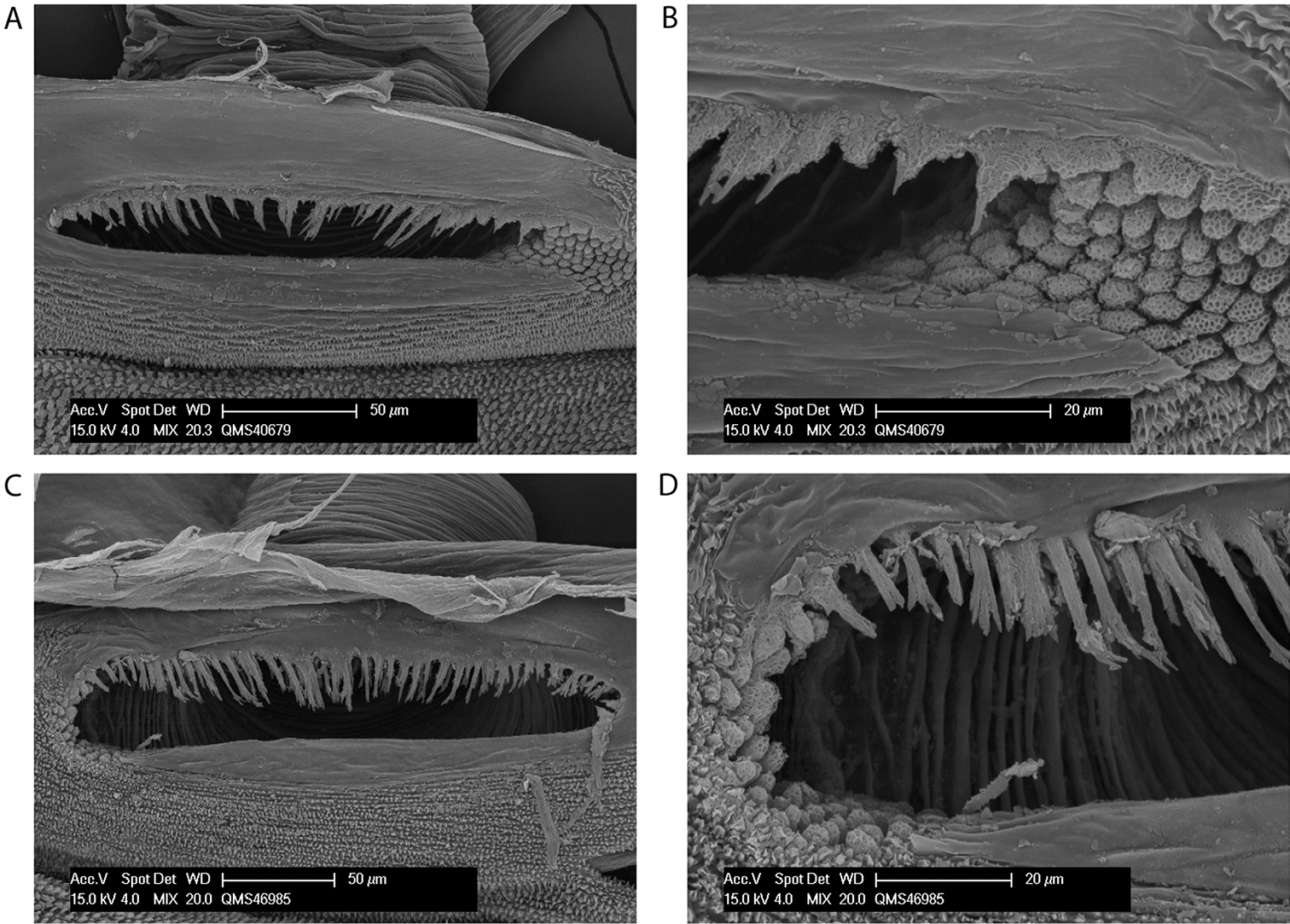

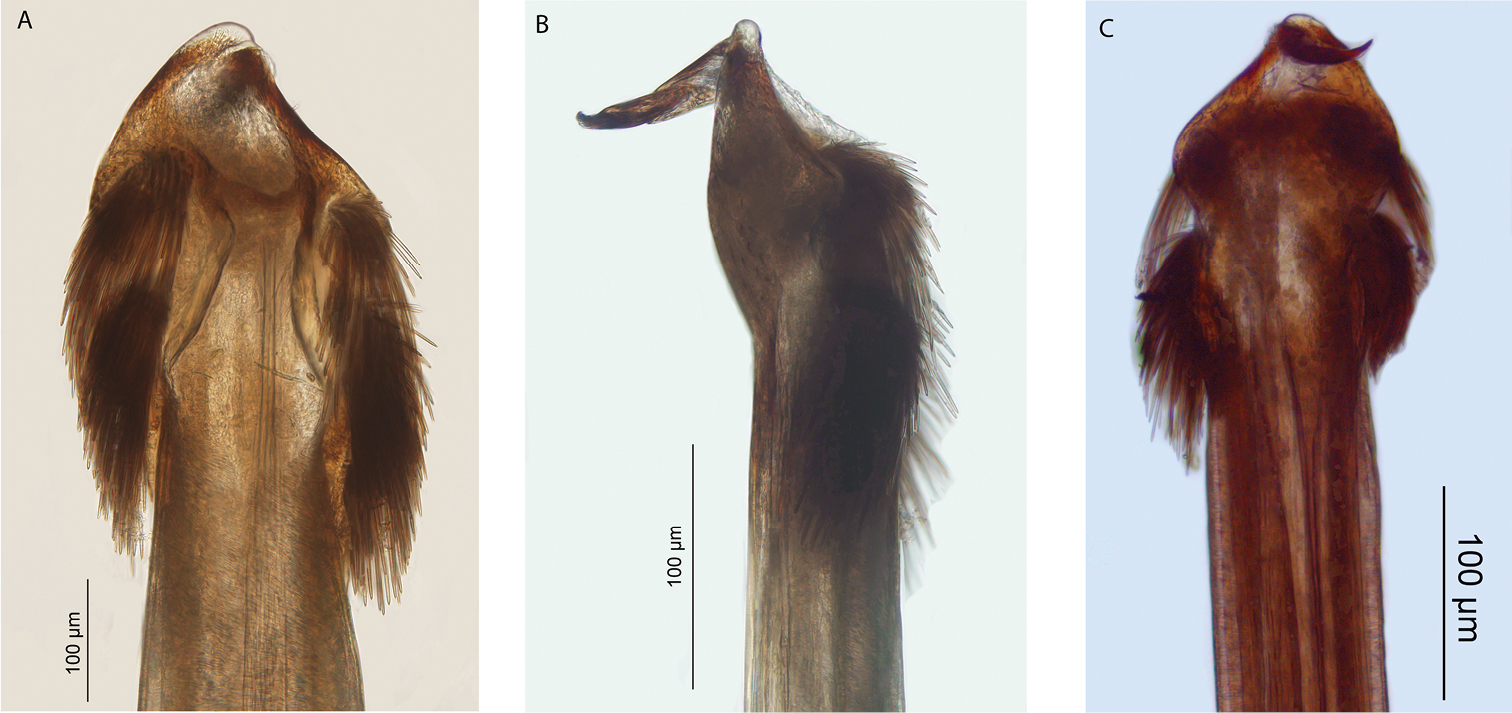

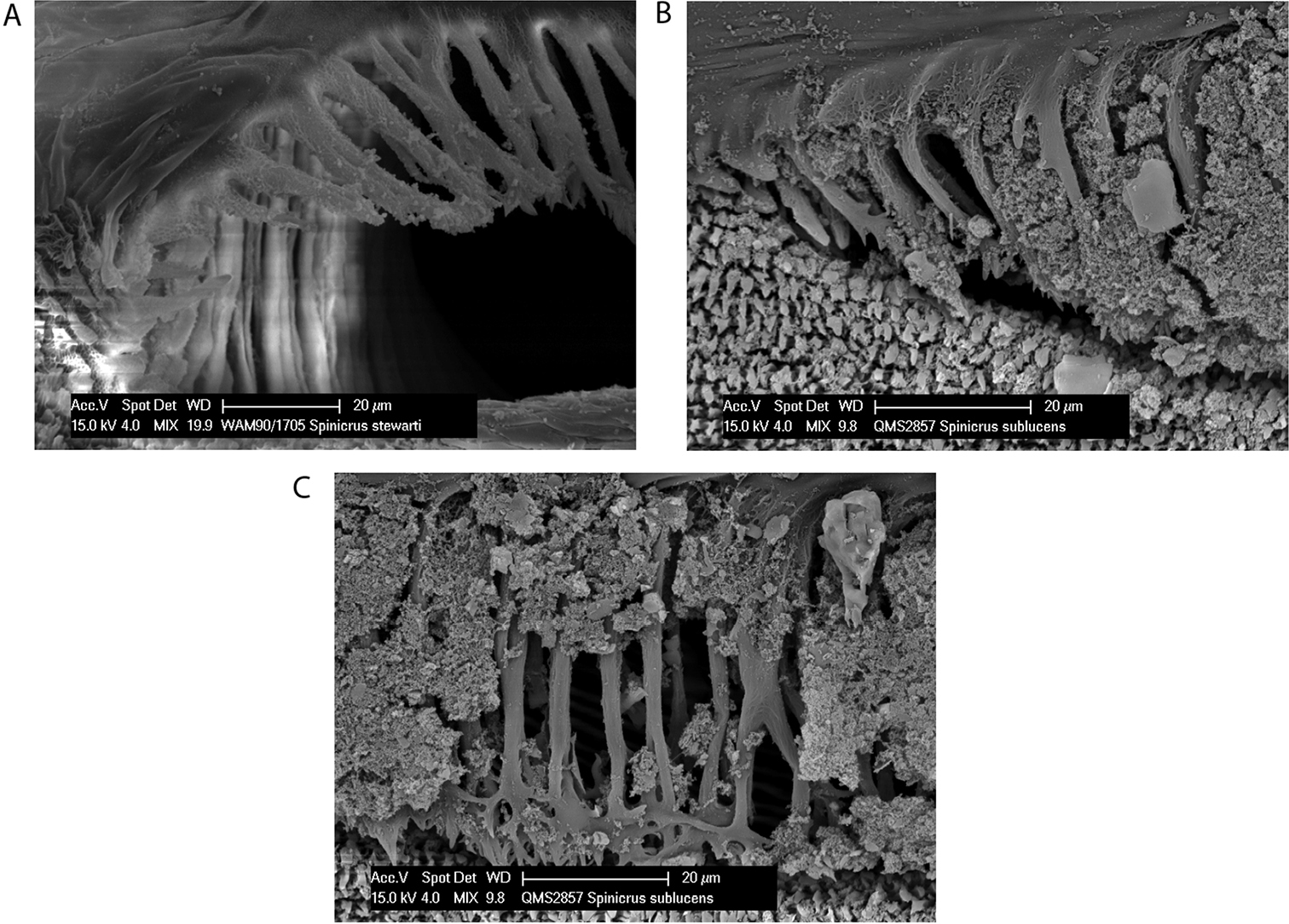

Spiracles of Megalopsalis minima species-group: a Megalopsalis porongorupensis b Megalopsalis walpolensis c Megalopsalis suffugiens d same, close-up of lateral corner showing area of reticulation.

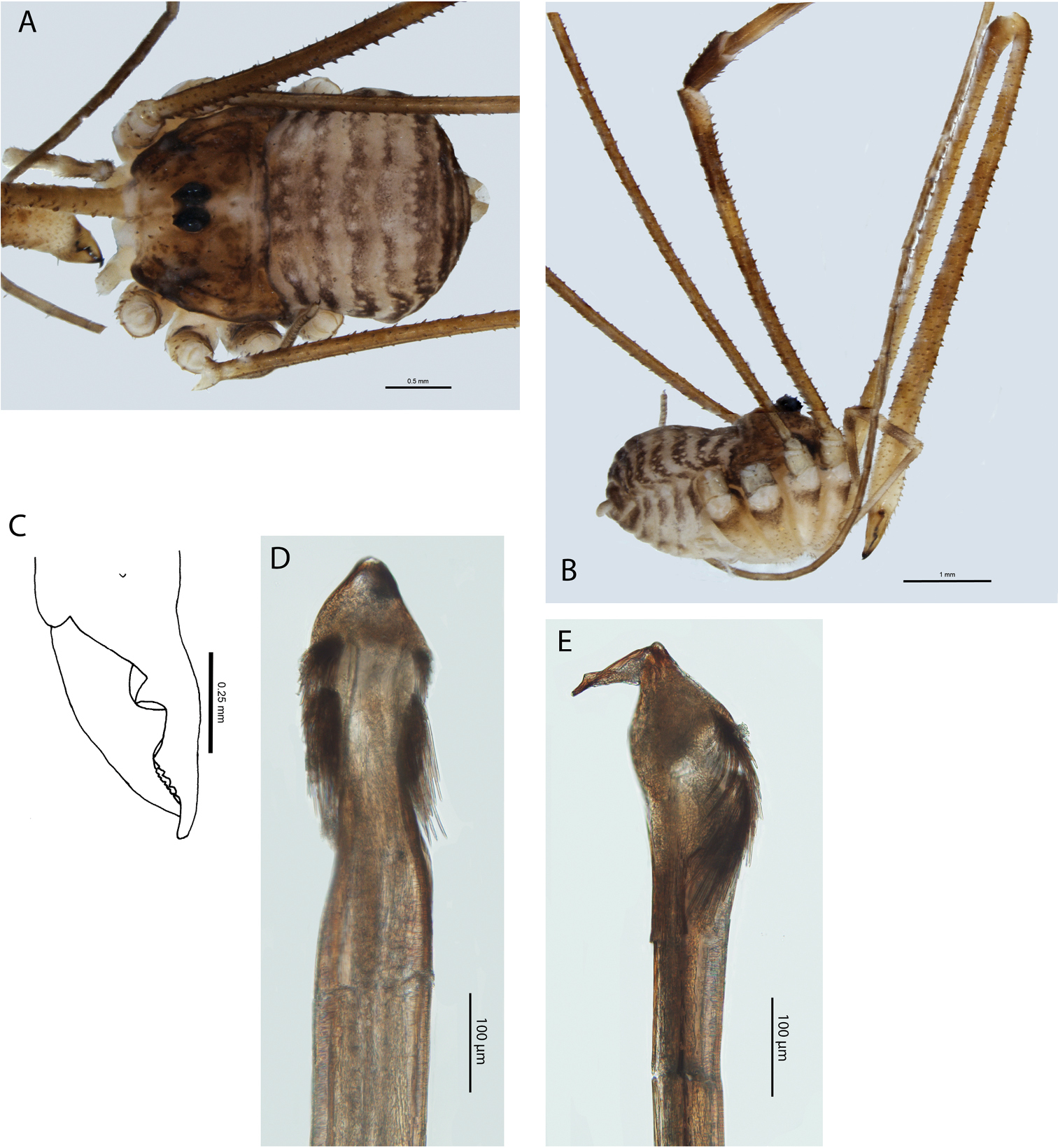

Megalopsalis minima, major male (all WAM T72169): a body, dorsal view b body, lateral view c right cheliceral fingers, frontal view d glans, ventral view e glans, right lateral view.

MAJOR MALE (N = 3). Prosoma length 0.85 (0.78–0.90), width 1.86 (1.74–1.92); total body length 2.37 (2.18–2.56). Dorsal prosomal plate golden brown; median prosomal area strongly denticulate, fewer denticles on margins of anterior and posterior prosomal areas. Ocularium black with row of denticles along edge on each side. Ozopore large, lenticulate. Dorsum of opisthosoma with alternating tan and dark brown mottled with tan stripes, and scattered iridescent white patches. Coxae tan with medium brown distal ends; venter of opisthosoma dark brown medially; tan dusted with black laterally.

Chelicerae. Segment I 5.81 (4.78–7.00), segment II 6.83 (6.10–7.88). Chelicerae golden brown with second segment tan distad; evenly denticulate. Fingers long; mobile finger crescent-shaped (Fig. 3c).

Pedipalps. Femur 0.96 (0.89–1.00), patella 0.44 (0.43–0.46), tibia 0.55 (0.54–0.59), tarsus 1.23 (1.21–1.26). Alternating tan and brown bands; femur without denticles. Femur to proximal part of tibia with longitudinal rows of large setae, distal tibia and tarsus with large setae interspersed among small setae. Inner dorsal distal patella with swelling but no distinct apophysis. Microtrichia on distal end of tibia and tarsus; claw with ventral tooth-row.

Legs. Femora 4.27 (3.82–4.55), 7.51 (6.92–7.92), 3.72 (3.48–3.96), 5.75 (5.33–5.94); patellae 0.87 (0.80–0.98), 0.96 (0.92–1.07), 0.81 (0.76–0.86), 0.95 (0.93–1.00); tibiae 3.96 (3.62–4.28), 8.15 (7.42–8.46), 3.67 (3.44–3.84), 5.79 (5.27–5.98). Femora with strong denticles. Patella I with two longitudinal rows of spines, one on each side; rows continue on tibia, dwindling distalwards. Patellae of other legs only lightly denticulate; tibiae smooth. Tibia II with 7–9 pseudosegments, tibia IV with two pseudosegments.

Penis (Figs 3d–e). Tendon long; waist in shaft behind bristle groups; left anterior bristle group reduced. Glans short, triangular in ventral view, not strongly flattened distally; dorsal side in line with shaft, evenly convex. Deep pores.

Spiracle. Spines almost entirely absent, residual reticulate bases only towards lateral corner; dense field of lace tubercles at lateral corner.

MINOR MALE (N = 7). Prosoma length 0.73 (0.55–0.83), width 1.82 (1.39–1.68); total body length 1.83 (1.45–2.25). As above, except for following.

Chelicerae. Segment I 0.96 (0.66–2.61), segment II 1.68 (1.27–3.44).

Pedipalps. Femur 0.84 (0.78–0.90), patella 0.37 (0.34–0.39), tibia 0.48 (0.43–0.53), tarsus 1.05 (0.93–1.10).

Legs. Femora 3.48 (3.20–3.70), 6.57 (6.27–6.79), 3.34 (3.00–3.52), 4.79 (4.30–5.00); patellae 0.72 (0.63–0.80), 0.83 (0.77–0.87), 0.72 (0.69–0.76), 0.83 (0.70–0.85); tibiae 3.46 (2.84–3.80), 7.02 (6.33–7.34), 3.26 (2.72–3.52), 4.74 (4.15–5.00). Patella I lightly denticulate, without longitudinal spine rows.

Unfortunately, the type specimen(s) of Megalopsalis minima were not available for the present study. This species has been identified based on its original description by

Females have been found in association with males of Megalopsalis minima, Megalopsalis porongorupensis and Megalopsalis walpolensis (unpublished observations, specimens in WAM). However, as no distinct morphotypes have been distinguished among the likely females, while the ranges of these species overlap, it has not been possible as yet to determine which females are assignable to which species.

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_porongorupensis

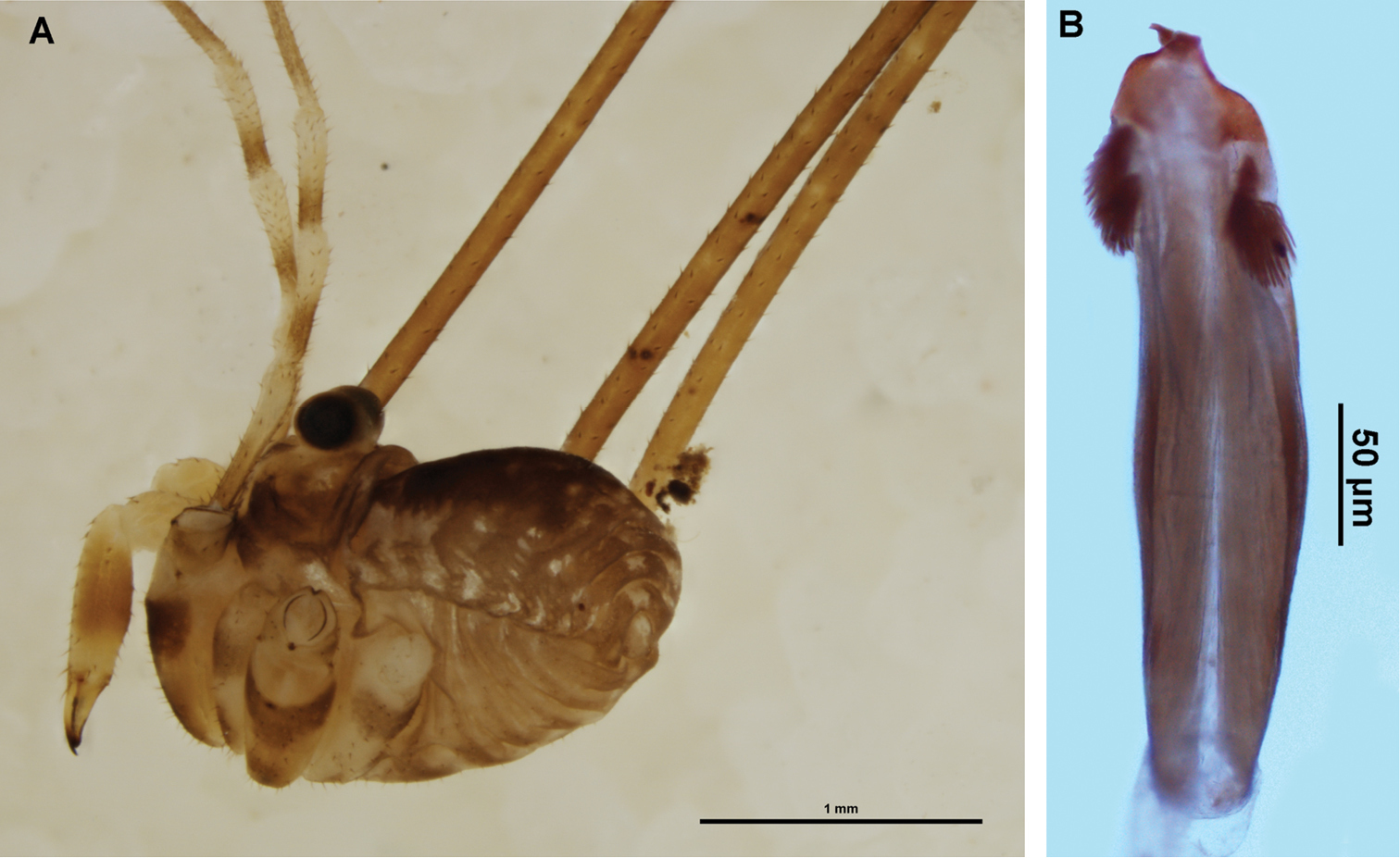

Figs 2a, 45 males, Glenbourne, Old Ellensbrook Road, S of Gracetown, Western Australia, 33°53'S, 115°00'E, 27–28 October 1996, L. Marsh et al., pitfalls (WAM T72175 [2 measured]; T72184 [1 measured]); 2 males, ditto, 27–29 December 1997, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfalls (WAM T72152–3; measured); 1 male, ditto, 33°54'50"S, 115°00'57"E, 24–26 October 1998, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72161; measured); 1 male, ditto, 33°54'32"S, 115°00'24"E, 20–23 October 2000, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72200); 1 male, ditto, 33°54'40"S, 115°00'34"E, 24-26 October 1998, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72173); 1 male, ditto, 25–27 October 2003, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72198; measured); 1 male, ditto, 33°54'35"S, 115°00'15"E, 30 October–1 November 1999, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72155; measured); 3 males, ditto, 33°54'50"S, 115°00'57"E, 30 October–1 November 1999, L. Marsh et al., dry pitfall traps (WAM T72143; 2 measured); 1 male, Pemberton, Crowea Block, Western Australia, 240 m, 17 December 1976, S. J. Curry, pitfall trap (WAM 90/1319); 2 males, ditto, 24 October 1977, S. J. Curry, ridge site, pitfall traps (WAM 90/1321–2); 1 male, ditto, 31 October 1977, S. J. Curry, ridge site, pitfall trap (WAM 90/1335); 1 male, ditto, 11 November 1977, S. J. Curry, ridge site, pitfall trap (WAM 90/1326); 1 male, Porongurup Range, Western Australia, 20 January 1932, E. W. Bennett (WAM 32/217); 1 male, Porongurup National Park, Porongurups, Western Australia, 34°40'55.8"S, 117°51'58.6"E, 570 m, 13 June 1996, S. Barrett, wet pitfalls (WAM T72214); 3 males, Mordalup Road, Unicup, Western Australia, 34°19'01"S, 116°31'49"E, 15 Oct 1999–31 Oct 2000, P. van Heurck, wet pitfalls (WAM T73035).

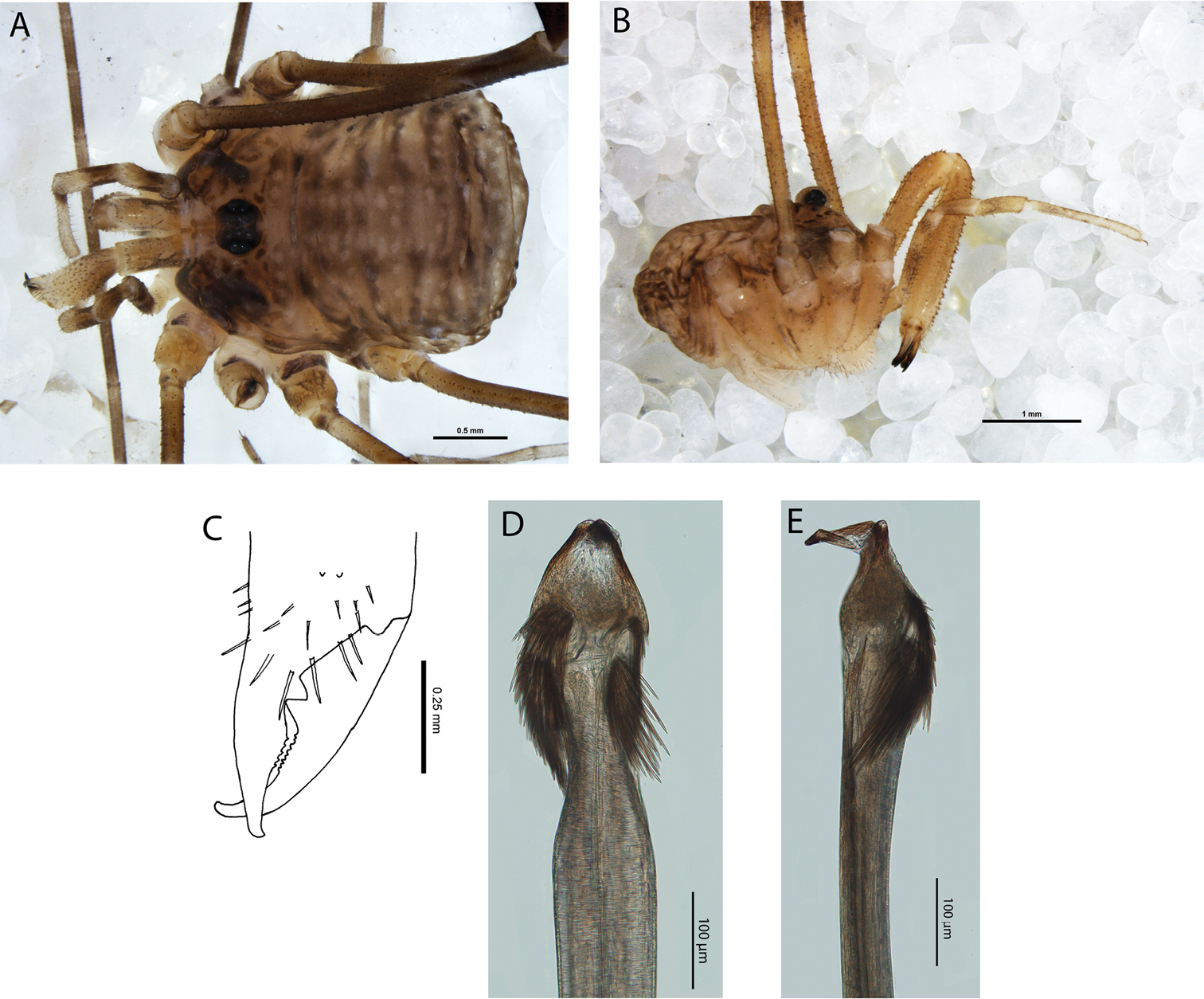

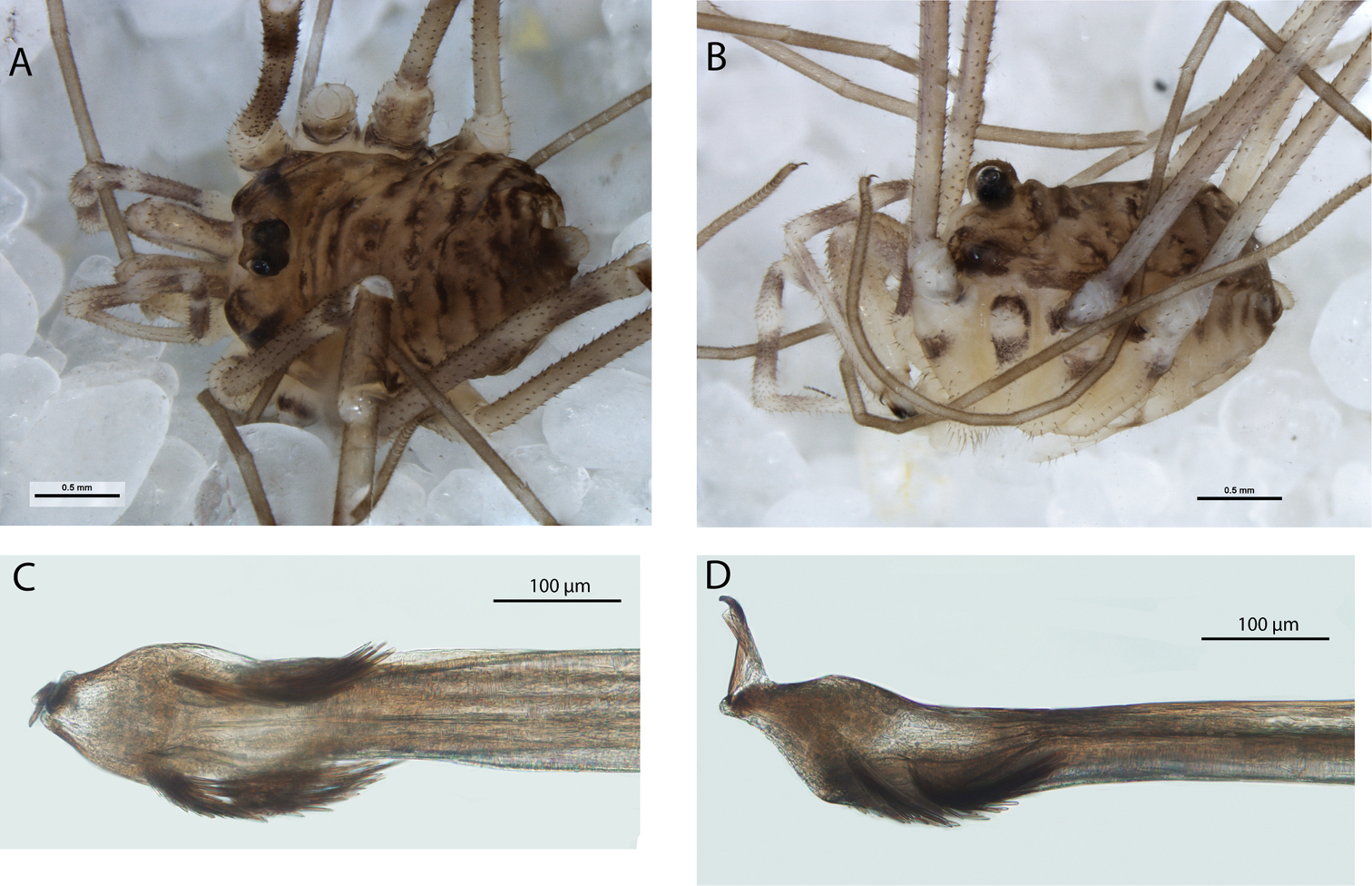

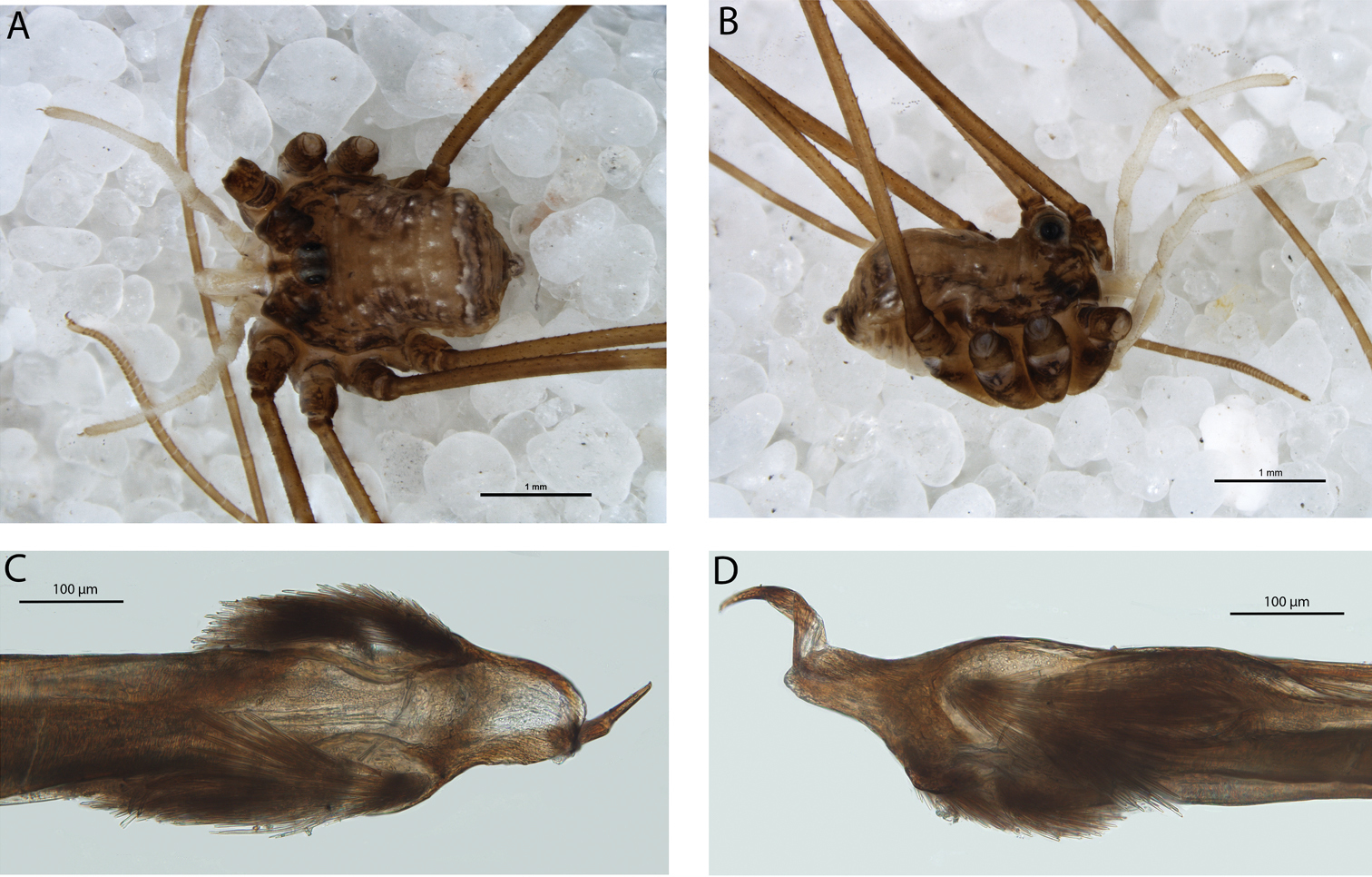

Megalopsalis porongorupensis is distinguishable from other members of the Megalopsalis minima-species group by the presence of denticulation on the pedipalp (

MALE (N = 10). Prosoma length 0.81 (0.65–0.91), width 1.55 (1.41–1.74); total body length 1.94 (1.70–2.33). Dorsal prosomal plate including ocularium tan with dark mottling; unarmed. Ozopore large. Dorsum of opisthosoma tan with iridescent white spots and broad white median stripe.

Chelicerae. Segment I 1.35 (0.69–2.20), segment II 2.04 (1.23–3.00). Tan; heavily and uniformly denticulate. Cheliceral fingers medium length; mobile finger crescent-shaped (Fig. 4c).

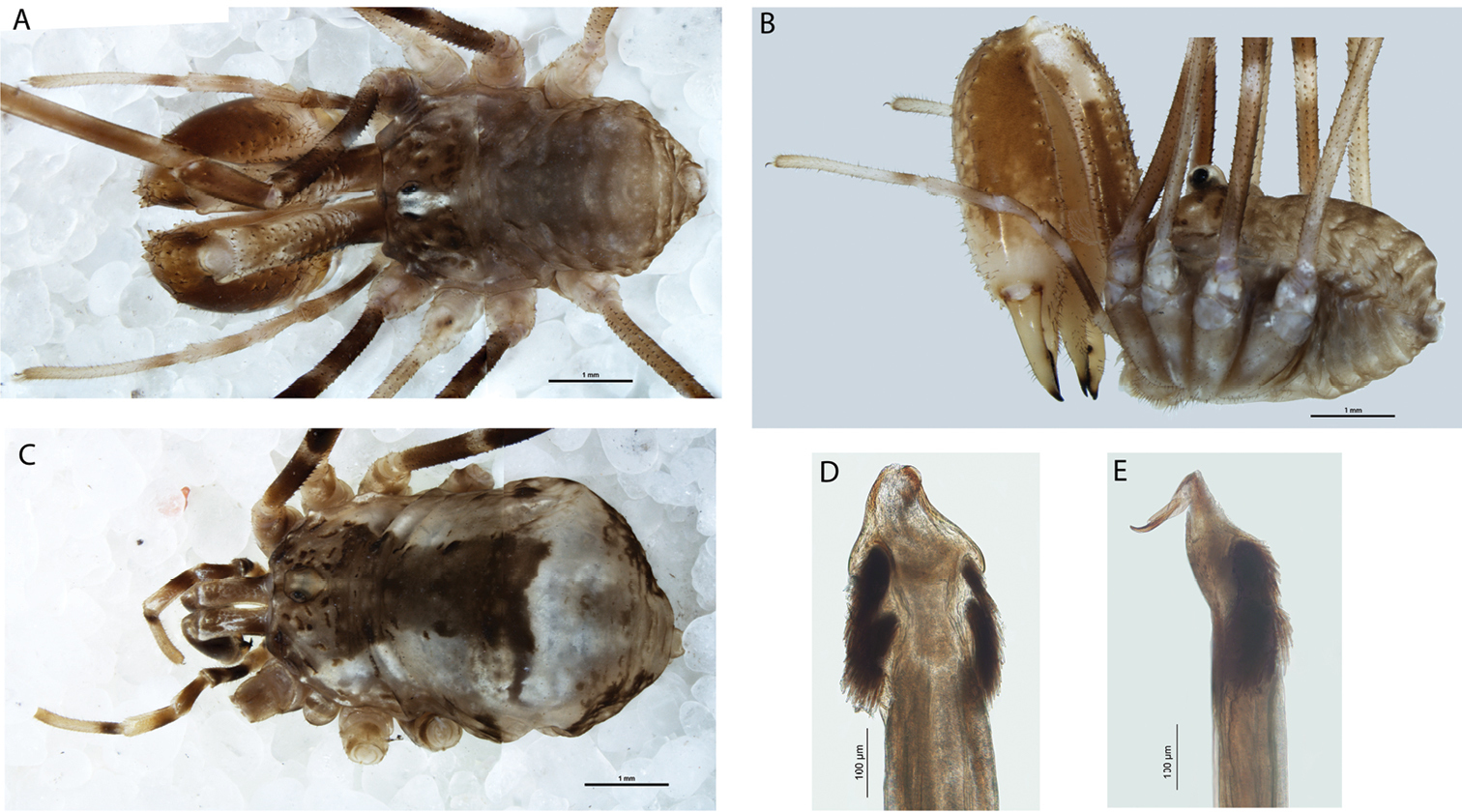

Megalopsalis porongorupensis, male: a body, dorsal view (WAM T72311) b body, lateral view (WAM T72203) c left cheliceral fingers, frontal view (WAM T72175) d glans, ventral view (WAM T72175) e glans, dorsolateral view (WAM T72175).

Pedipalps. Femur 0.83 (0.75–1.00), patella 0.38 (0.31–0.45), tibia 0.45 (0.40–0.52), tarsus 1.05 (0.94–1.19). Tan. Femur and patella heavily denticulate, few scattered large setae only; tibia lightly denticulate proximally. Inner dorsal distal patella slightly bulging but no distinct apophysis. Microtrichia on distal part of tibia and tarsus; claw with ventral tooth row.

Legs. Femora 3.46 (3.08–3.92), 6.68 (6.00–7.34), 3.24 (2.92–3.48), 5.20 (4.65–5.67); patellae 0.73 (0.66–0.84), 0.84 (0.67–0.89), 0.66 (0.56–0.78), 0.80 (0.64–1.00); tibiae 3.16 (2.88–3.42), 7.12 (6.60–7.83), 3.03 (2.70–3.24), 4.78 (4.15–5.27).

Penis (Figs 4d–e). Glans short, dorsal edge in line with shaft; stylus at 90° to glans and shaft. Left anterior bristle group reduced; waist in shaft behind bristle groups. Deep pores.

Spiracle (Fig. 2a). Spines almost entirely absent, residual reticulate bases only towards lateral corner; dense field of lace tubercles at lateral corner.

Unfortunately, the type specimen(s) of Megalopsalis porongorupensis were not available for the present study. This species has been identified based on its original description by

This species shows a relatively large degree of difference in cheliceral size between the largest and smallest individuals, but there is no clear clustering into a larger and a smaller morph.

http://zoobank.org/EA5093FB-A854-4AE1-B512-5789F226176C

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_suffugiens

Figs 2c–d, 5Male holotype. Balgair Station, cave 6N–612, Western Australia, 14 September 1999, N. Poulter, from ceiling adjacent to cave entrance (WAM T72303).

Paratypes. 1 male, Balgair Station, cave 6N–1536, Western Australia, 13 September 1999, N. Poulter, walking on damp earth floor (WAM T72299); 1 male, ditto, c. 11 m below cave entrance (WAM T72307); 1 female, Balgair Station, cave 6N-1616, Western Australia, 15 September 1999, P. Devine, N. Poulter, rockhole cave (WAM T72287); 2 males, 1 female, Hampton Tableland, Mundrabilla Station, cave 6N–326, 22 September 1999, P. Devine, N. Poulter, from cave walls in dark zone, largest [female] from entrance lip at night fall (WAM T72298); 1 female, Madura Plains Station (=Moonera Station), cave 6N–1617, 17 September 1999, R. Anderson, N. Poulter, from cave ceiling in dark zone (WAM T72305); 1 female, Nullarbor area, cave 6N–481, 1 October 1994, R. Foulds, from roof of entrance squeeze (WAM T72141).

Megalopsalis suffugiens is readily distinguished from other species of the Megalopsalis minima-species group by its pale coloration without dark transverse bands on the opisthosoma (Fig. 5a–b). The spines on the legs (if present) are also proportionately longer and more slender than those found in other species. It can also be distinguished from Megalopsalis minima by the lack of denticles on the ocularium and median propeltidial area (Fig. 5a) and from Megalopsalis porongorupensis by the lack of denticles on the pedipalps.

Megalopsalis suffugiens, male (all WAM T72299): a body, dorsal view b body, lateral view c glans, ventral view d Glans, right lateral view.

MALE (N = 5). Prosoma length 0.75 (0.68–0.83), width 1.69 (1.56–1.86); total body length 2.21 (2.08–2.30). Dorsal prosomal plate unarmed (Balgair Station specimens) or with few denticles on anterior propeltidial area (Hampton Tableland specimens); patched tan and iridescent white with scattered darker mottling. Mesopeltidium with distinct transverse row of black setae. Metapeltidium and anterior part of opisthosoma mottled tan and silver. Posterior part of opisthosoma silver with transverse bands of dark brown mottling.

Chelicerae. Segment I 1.47 (0.78–2.22), segment II 2.44 (1.56–3.28). Both segments tan; lightly denticulate with reduced denticulation distad on both segments. Segment II slightly inflated distad. Cheliceral fingers long, slender; mobile finger crescent-shaped.

Pedipalps. Femur 1.01 (0.87–1.09), patella 0.51 (0.50–0.54), tibia 0.57 (0.54–0.64), tarsus 1.27 (1.20–1.33). White with tan patches and black setae; femur with longitudinal rows of setae; patella and tibia with black setae laterally and medially, midline glabrous; no apophysis. Microtrichia over greater part of tarsus and tibia; claw with ventral tooth row.

Legs. Femora 3.83 (3.17–4.45), 7.14 (6.38–7.77), 3.10 (2.66–3.36), 4.94 (4.10–5.56); patellae 0.90 (0.83–0.99), 1.05 (0.98–1.12), 0.85 (0.78–0.94), 0.99 (0.90–1.06); tibiae 3.71 (3.34–4.00), 7.42 (6.81–7.89), 3.57 (2.90–4.05), 4.91 (4.10–5.52). Trochanters iridescent white; unarmed or with single anterior spine on trochanters I and III. Legs tan; femur I with sparse, slender spines, reduced to only a few dorsally in some specimens; femur II unarmed or with few spines near base; remaining segments unarmed. Femora and patellae with scattered black setae; tibiae and tarsi densely covered in small setae. Tibia II with 11 to 13 pseudosegments; tibia IV with two or three pseudosegments.

Penis (Figs 5c–d). Shaft broad, tendon relatively short; bristle groups well-developed. Glans short, broad, triangular in dorsal view; in line with shaft; dorsal side evenly convex; not significantly flattened distally. Pores shallowly recessed.

Spiracle (Figs 2c–d). No occluding spines; lace tubercles at lateral corner reduced to patch of reticulation.

FEMALE (N = 4). Prosoma length 1.16 (0.61–1.45), width 2.13 (1.98–2.28); total body length 3.83 (3.40–4.40). As for male, except for following: Dorsum unarmed.

Chelicerae. Segment I 0.75 (0.66–0.81), segment II 1.58 (1.55–1.62). Unarmed.

Pedipalps. Femur 1.31 (1.28–1.34), patella 0.68 (0.65–0.71), tibia 0.78 (0.73–0.83), tarsus 1.65 (1.63–1.67). Patella and tibia more densely setose medially than male.

Legs: Femora 4.68 (4.45–4.95), 9.28 (8.73–10.23), 4.01 (3.72–4.28), 5.95 (5.63–6.16); patellae 1.18 (1.07–1.24), 1.42 (1.32–1.45), 1.11 (1.03–1.19), 1.19 (1.13–1.24); tibiae 4.79 (4.65–4.96), 9.77 (9.12–10.38), 4.44 (4.28–4.63), 6.05 (5.81–6.25). Femora and patellae with longitudinal rows of small spines.

Males show a noticeable variation in the size of the chelicerae that correlates with the development of armature on the legs; however, the variation is not as large as that found in Megalopsalis minima, and it is uncertain at present whether variation is continuous or a distinction occurs between major and minor males. Further specimens are also required to establish whether the difference in dorsal armature recorded above between Balgair Station and Hampton Tableland specimens indicate separate populations in these localities.

From the Latin suffugio, to take shelter, to reflect the finding of specimens of this species within caves in the arid Nullarbor.

All specimens of Megalopsalis suffugiens recorded to date were collected in caves; however, Megalopsalis suffugiens does not show any obvious troglobitic adaptations. The eyes remain well-developed and the legs are proportionately only slightly longer than in other Megalopsalis species. It seems more likely that Megalopsalis suffugiens only uses the caves as damp refugia during the day, emerging at night to feed. This suggestion is supported by the collection of at least one specimen (WAM T72298) from a cave entrance at nightfall.

http://zoobank.org/9ACD0DA5-BE0D-4FCB-BEB7-D2E4F195C8E9

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_walpolensis

Figs 2b, 6Male holotype. Walpole-Nornalup National Park, Knoll Drive, Walpole, Western Australia, 34°59'43"S, 116°43'12"E, 29 October 2006, M. L. Moir, A. Sampey (WAM T78848).

Paratype. 1 male, Mt Shadforth, Western Australia, 34°58’04"S, 117°16’47"E, 6 November 2006, M. L. Moir, D. Jolly, in leaf litter (WAM T78856).

The features of Megalopsalis walpolensis appear intermediate between those of Megalopsalis minima and Megalopsalis porongorupensis. It differs from Megalopsalis minima in lacking significant denticulation on the ocularium and propeltidium (Fig. 6a) and from Megalopsalis porongorupensis in lacking denticles on the pedipalps.

Megalopsalis walpolensis, male (all WAM T78848): a body, dorsal view b body, lateral view c glans, ventral view d glans, left lateral view.

Locality map for Megalopsalis species (excluding Megalopsalis serritarsus-group) in eastern Australia: grey shading = Megalopsalis tasmanica and Megalopsalis nigricans; circle with dot = Megalopsalis sublucens; solid square = Megalopsalis thryptica; solid circle = Megalopsalis stewarti; solid star = Megalopsalis caeruleomontium; square with dot = Megalopsalis coronata, triangle with dot = Megalopsalis puerilis, solid triangle = Megalopsalis atrocidiana.

MALE (N = 2). Prosoma length 0.65 (0.55–0.74), width 1.44 (1.34–1.53); total body length 2.22 (2.13–2.30). Anterior propeltidial area cream, remainder of propeltidium golden-brown with mottled black patches on anterior corners of dorsal prosomal plate and lateral shelves. Prosoma mostly unarmed, except few small scattered denticles on lateral edge of dorsal prosomal plate near odoriferous glands. Odoriferous glands visible as black patches through cuticle. Ocularium dark golden-brown, with row of small low denticles around each eye. Mesopeltidium, metapeltidium and opisthosoma with transverse band of mottled black across golden-brown background of each segment, broken by tan or iridescent white spots. Coxae cream with mottled purple patches at distal ends; venter of opisthosoma cream dusted with purple, condensing to more solid patches laterally.

Chelicerae. Segment I 0.73 (0.67–0.79), segment II 1.42 (1.25–1.59). Segment I mottled purple on cream background with purple mottling more solid laterally than medially; scattered denticles dorsally. Segment II cream, mottled with purple proximally, densely denticulate proximally with denticles thinning until distal third is unarmed. Cheliceral fingers short, lateral margin evenly rounded.

Pedipalps. Femur 0.90 (0.89–0.91), patella 0.42 (0.40–0.44), tibia 0.50 (0.48–0.52), tarsus 1.11 (1.07–1.14). Cream banded with purple, with cream stripe down dorsal midline; unarmed. No patellar apophysis; black setae denser on medial side of patella but not hypersetose. Microtrichia on tarsus, except for proximal third, and distalmost end of tibia. Tooth-comb on claw.

Legs. Femora 3.48 (3.44–3.52), 6.20 (6.15–6.24), 3.33 (3.32–3.34), 5.05 (4.98–5.11); patellae 0.81 (0.78–0.83), 1.05 (1.03–1.06), 0.82 (0.81–0.83), 0.95; tibiae 3.42 (3.40–3.44), 6.95 (6.93–6.96), 3.16 (3.13–3.19), 4.90 (4.84–4.96). Trochanters white-cream mottled with purple, unarmed. Femora golden-brown proximally, with cream band beginning distad of halfway, followed by purple band, then cream distal end. Patellae dark cream dusted with black, tibiae and metatarsi banded cream and dusty black, tarsi cream. Femora and distal ends of patellae with broken rows of dorsal denticles, remaining segments unarmed. Tibia II with seven pseudosegments, tibia IV undivided.

Penis (Figs 6c–d). Left anterior bristle group somewhat reduced, remaining bristle groups well-developed. Glans short, broad, triangular in dorsal view; roughly in line with shaft; dorsal side evenly convex; not significantly flattened distally. Deep pores.

Spiracle (Fig. 2b). Spines entirely absent; dense patch of lace tubercles at lateral corner.

From the type locality, Walpole, with the suffix –ensis indicating geographic origin.

http://zoobank.org/10CF153B-F43C-4FFE-9511-EC6BE7320776

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_atrocidiana

Figs 8, 9a–cMale holotype. Central Queensland, Mt Dalrymple, 21°03'S, 148°38'E, 1200 m, 21 December 1992–10 January 1993, ANZSES Expedition, flight intercept trap (QM S35935).

Paratype. 1 female, ditto (QM S35935).

Megalopsalis atrocidiana differs from all other long-legged Enantiobuninae in the presence of transverse rows of spines on the opisthosoma (Fig. 8a); these are present in reduced form in the females as well as the males.

Megalopsalis atrocidiana (all QM S35935): a body of male, dorsal view b body of male, lateral view c body of female, dorsal view d glans, ventral view e glans, right lateral view.

MALE (N = 1). Prosomalength 2.18, width 1.26; total body length 2.66. Body medium brown; darker mottling on prosoma. Dorsal prosomal plate sharply denticulate; denticles along posterior margins of prosomal segments. Lateral spines on each side of metapeltidium. Ocularium with high spines. Ozopore large. Opisthosoma with transverse rows of spines on raised mounds along midlines of first four segments. Coxae golden brown with dark brown patches distally; venter of opisthosoma light grey-brown.

Chelicerae. Segment I 1.40, segment II 2.53. Segment II darker than segment I; distal end of segment I white. Both segments evenly denticulate. Cheliceral fingers long, mobile finger angular crescent-shaped.

Pedipalps. Femur 1.15, patella 0.53, tibia 0.63, tarsus 1.42. Proximal half of femur brown, distal half of femur to tibia white, tarsus tan. Unarmed; no apophysis on patella. Plumose setae present medially (Fig. 9c). Microtrichia on distal three-quarters of tarsus; claw with ventral tooth-row.

Megalopsalis atrocidiana and Megalopsalis coronata, SEM images: a Megalopsalis atrocidiana, spiracle b same, close-up of lateral corner c Megalopsalis atrocidiana, right pedipalp, medial view of patella and tibia, showing plumose setae d Megalopsalis coronata, left pedipalp, medial view of distal end of patella, showing mixture of plumose and non-plumose setae.

Legs. Femora –, 6.77, 3.48, 5.41; patellae –, 1.19, 1.01, 1.11; tibiae –, 7.89, 3.24, 5.03. Golden brown. Trochanters with robust spines on prolateral face. Leg I not preserved. Femora of remaining legs denticulate; patellae with longitudinal rows of small denticles; remaining segments unarmed. Tibia II with seven or eight pseudosegments; tibia IV undivided.

Penis (Figs 8d–e). Left anterior bristle group slightly reduced, remaining bristle groups well developed. Glans of medium length, edges converging in ventral view.

Spiracle (Figs 9a–b). Dense curtain of robust reticulate spines extending partway across spiracle; terminations of spines multifurcate but not palmate; lace tubercles in lateral corner, with small number of reticulate spines at lateral end of posterior margin.

FEMALE (Fig. 8c; N = 1). Prosoma length 1.5, width 2.3; total body length 3.48. Anterior propeltidial area tan, remainder of propeltidium mottled medium brown. Ocularium with row of denticles on each side. Mesopeltidium medially medium brown, laterally tan with black mottling; small denticles medially. Metapeltidium and first three segments of opisthosoma medially medium brown with black patches on edge of medial area, laterally tan mottled with black. Metapeltidium and first four segments of opisthosoma with transverse rows of small denticles. Posterior part of opisthosoma tan mottled with black. Coxae patched tan and dark brown; venter of opisthosoma grey with longitudinal rows of dark brown patches.

Chelicerae. Segment I 0.77, segment II 1.65. Segment I tan with dark brown lateral patches proximodorsally; segment II golden brown with tan fingers. Unarmed.

Pedipalps. Femur 1.28; patella 0.59; tibia 0.72; tarsus 1.60. Femur dark brown on proximal half, tan on distal half with golden brown patch on distalmost end; patella and tibia each golden brown proximally, tan distally; tarsus tan. Unarmed; no apophysis on patella.

Legs: Femora 3.56, 6.77, 3.40, –; patellae 1.17, 1.23, 1.11, –; tibiae 3.84, 7.69, 3.24, –. Banded tan and medium brown; longitudinal dorsal rows of denticles on femora and patellae. Tibia II with eight pseudosegments; leg IV not preserved.

From the Latin atrox, cruel, and the goddess Diana. The transverse rows of mounds on the opisthosoma are reminiscent of the figure known as Diana of Ephesus, while the epithet ‘cruel’ refers to the addition of a spine on each of the mounds.

http://zoobank.org/F531E2F7-3799-4970-AA4A-26F53A9F95B3

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_caeruleomontium

Figs 10–11Male holotype. Mt Kembla, Sydney Catchment Authority Reserve, New South Wales, 34°26'33"S, 150°44'24"E, 11–15 December 1998, L. Gibson, pitfall traps (AMS KS63019; measured).

Paratypes. 2 males, 1 female, Blue Mountains road to Ingar picnic area, New South Wales, 33°46'03"S, 150°24'30"E, 3 October 1996, pitfall trap (AMS KS57166, KS57168; all measured); 3 males, Clyde Mountain, 35°33'S, 149°57'E, 24 October 1968, G. B. M[illedge] (AMS KS65018; measured); 3 males, 2 females, Kirkconnell, 28 May 1972, G. S. Hunt (AMS KS21480; 2 females measured); 1 male, Mt Shivering (near pluviometer), E of Oberon, New South Wales, 23 September 1972, G. S. Hunt (AMS KS21484; measured); 4 males, 6 females, Mt Werong (near pluviometer), New South Wales, 3 July 1972, G. S. Hunt (AMS KS23117; 2 males, 5 females measured); 4 males, 3 females, Muogamarra Nature Reserve, Pacific Highway, 0.7 km SE of Bird Gully Swamp, New South Wales, 33°33'42"S, 151°11'15"E, 2-16 December 1999, M. Gray, G. Milledge, H. Smith, pitfall traps (AMS KS62256; 2 females measured); 1 male, hill NE of Oberon, 10 June 1972, G. S. Hunt (AMS KS21483; measured); 1 male, “Scalloway” pool, Geringong, New South Wales, 23 November 1986, G. Wishart, found ‘walking on water’ (AMS KS17413, measured).

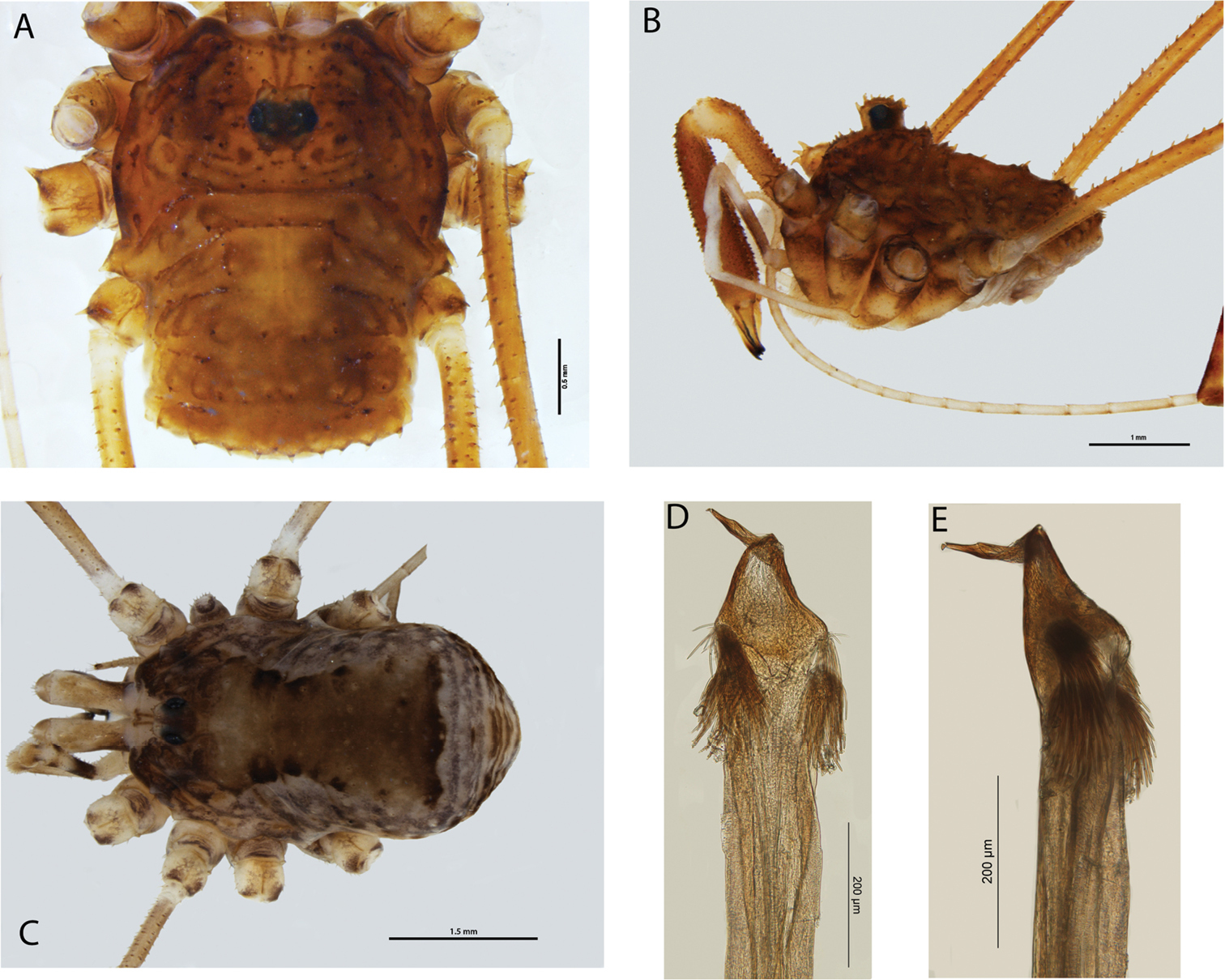

Megalopsalis caeruleomontium differs from other species of Megalopsalis in the presence of setae on the mobile finger of the chelicerae (Fig. 10b). Most males (except the smallest) can also be distinguished by the inflated second segment of the chelicerae (Fig. 10b). Megalopsalis caeruleomontium has a relatively flattened penis compared to other Megalopsalis species except Megalopsalis nigricans; the glans is rather short, with the sides becoming subparallel distally (Figs 10d–e).

Megalopsalis caeruleomontium: a body of male, dorsal view (AMS KS63019) b body of male, lateral view (AMS KS63019) c body of female, dorsal view (AMS KS57168) d glans, ventral view (AMS KS63019) e glans, right lateral view (AMS KS63019).

MALE (N = 10). Prosoma length 1.17 (0.88–1.46), width 2.34 (1.98–2.50); total body length 3.25 (2.81–3.88). Propeltidium light orange-brown spotted with white and dark brown patches. Anterior propeltidial area pinkish-brown, with diverging dark-brown lines from ocularium to anterior margin, and dark-brown area around short supracheliceral groove on sharply downturned face. Prosoma unarmed. Ocularium bright white with light orange-brown base and behind eyes; postocularium bright white. Mesopeltidium, metapeltidium and first four segments of opisthosoma grey-brown with slightly lighter median band and distinctive transverse row of black setae in lighter spots across each segment. Posterior part of opisthosoma yellow-brown dusted with dark-brown; anal operculum silver. Coxae pinkish-brown with median white areas proximally; venter of opisthosoma grey-brown.

Chelicerae. Segment I 2.26 (0.57–3.26), segment II 3.36 (1.24–4.55). Segment I medium-brown dorsally and on proximal two-thirds laterally, peach-coloured ventrally and distolaterally, white patch at distolateralmost end with ventrolateral medium-brown patch directly underneath it; denticulate dorsally and on ventrolateral and ventromedial edges. Segment II strongly inflated in larger specimens to not inflated in smallest specimens, proximally mottled medium-brown and pink dorsally, medium-brown laterally, peach ventrally; distally pink-cream, fingers yellow-cream; denticulate dorsally and ventrolaterally. Cheliceral fingers bowed apart proximally in larger specimens, less or not bowed in smaller specimens.

Pedipalps. Femur 1.29 (0–1.46), patella 0.55 (0.37–0.64), tibia 0.78 (0.48–0.95), tarsus 1.63 (1.08–1.91). Trochanter and proximalmost part of femur cream; proximal two-thirds of femur medium-brown, then peach band, then light-brown band; patella pink-brown; tibia pink-brown proximally, cream distally; tarsus pink-brown at proximalmost end, remainder cream. No patellar apophysis. Microtrichia on tarsus and distal third of tibia; tooth-comb on claw.

Legs. Femora 4.26 (3.72–4.65), 7.29 (6.50–8.15), 3.97 (3.60–4.25), 5.90 (5.31–6.28); patellae 1.11 (0.91–1.23), 1.26 (1.06–1.44), 1.08 (0.80–1.30), 1.23 (0.97–1.37); tibiae 3.96 (3.31–4.28), 7.35 (6.50–8.00), 3.81 (3.14–4.10), 5.48 (4.67–6.00). Trochanters pinkish-cream, unarmed. Legs I and III medium-brown with cream bands, legs II and IV yellow-brown. Femora denticulate, with larger denticles dorsally than ventrally; fewer denticles dorsally on patellae, remaining segments unarmed.

Penis (Fig. 10d–e). Tendon long; bristle groups well-developed. Glans in line with shaft; dorsoventrally flattened for entire length with bases of bristle groups (especially left) consequently more ventral than lateral; glans short, sides converging in ventral view. Deep pores.

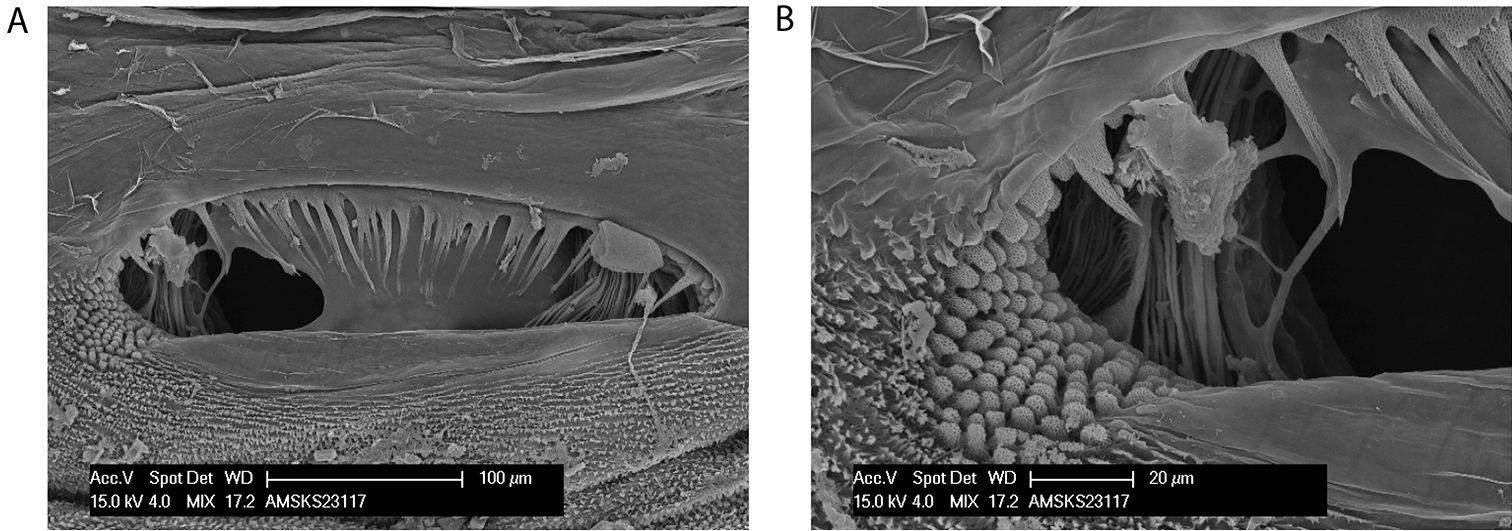

Spiracle (Fig. 11). Sparse curtain of slender reticulate spines extending only partway across spiracle; terminations of spines multifurcate; dense patch of lace tubercles at lateral corner.

FEMALE (Fig. 10c; N = 10). Prosoma length 1.30 (1.03–1.74), width 2.29 (2.08–2.59); total body length 4.60 (3.88–6.13). Propeltidium medium-grey-brown with dark-brown patches; prosoma unarmed. Ocularium grey-brown, unarmed. Mesopeltidium, metapeltidium and first three segments of opisthosoma medially dark-grey-brown, laterally whitish-grey with dark-brown patches on lateral margins. Posterior part of opisthosoma whitish-grey with mottled dark-brown patches laterally. Coxae light-brown mottled with white proximally followed by central cream band, medium-brown distally darkening to dark-brown pro- and retrolaterally. Mouthparts and genital operculum light tan. Venter of opisthosoma medium-orange-brown densely mottled with silver-white.

Megalopsalis caeruleomontium: a spiracle b same, close-up of lateral corner.

Chelicerae. Segment I 0.84 (0.72–0.95), segment II 1.66 (1.49–1.79). Dark orange-brown reticulated with silver dorsally and large silver-white patch distolaterally on first segment; unarmed.

Pedipalps. Femur 1.21 (1.14–1.38), patella 0.55 (0.50–0.59), tibia 0.78 (0.70–0.84), tarsus 1.55 (1.42–1.67). Femur light tan at proximalmost end, remainder medium brown; patella medium brown with small silver patches distolaterally; tibia and tarsus each proximally medium brown, distally light tan silvered dorsally. No apophysis or hypersetose areas; microtrichia over entire length of tibia and tarsus.

Legs. Femora 3.57 (3.38–3.92), 6.30 (5.97–7.23), 3.37 (3.17–3.86), 5.20 (4.94–5.63); patellae 1.10 (1.00–1.15), 1.22 (1.15–1.31), 1.06 (0.95–1.15), 1.18 (1.03–1.26); tibiae 3.40 (3.22–3.76), 6.31 (6.07–6.85), 3.26 (3.06–3.60), 4.84 (4.45–5.06). Trochanters grey-tan mottled with white, unarmed. Legs banded medium brown and light tan, with tan bands overlain by silver from distalmost end of femur to tibia. Femora and patellae with longitudinal rows of small denticles.

From the Latin words caeruleus, blue, and mons, mountain: “of the Blue Mountains”, in reference to the distribution of this species.

Males of this species vary significantly between the largest and smallest individuals in the development of the chelicerae, from inflated with bowed fingers in the largest specimens to slender with unbowed fingers in the smallest. However, variation appears to be more or less continuous (albeit with large individuals distinctly more numerous than small individuals) without a clear division between morphs.

http://zoobank.org/ACE42F7E-1AB9-48CE-A102-39E2530A452F

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_coronata

Figs 9d, 12, 13a–bMale holotype. Queensland, Sunday Creek, 18 December 1996–20 January 1997, G. Monteith, rainforest intercept (QM S40679).

Paratypes. 1 male, ditto (QM S40679); 1 male, ditto, Conondale Range, 900 m, 2 March–12 April 1992, D. J. Cook, rainforest pitfall (QM S74237).

Megalopsalis coronata is distinguished from all other Megalopsalis species except Megalopsalis tanisphyros, Megalopsalis puerilis and Megalopsalis sublucens by its small, unarmed chelicerae. It is distinguished from Megalopsalis tanisphyros by the absence of a pedipalpal patellar apophysis, from Megalopsalis puerilis by the presence of denticles on the ocularium, and from Megalopsalis sublucens by the absence of ventral brush-like bristles on distitarsi III and IV. The glans of Megalopsalis coronata is relatively long compared to other Megalopsalis species, with a lower angle of convergence between the sides in ventral view (Fig. 12c).

Megalopsalis coronata, male (all QM S74237): a body, dorsal view b body, lateral view c glans, ventral view d glans, right lateral view.

MALE (N = 3). Prosoma length 0.97 (0.93–1.04), width 1.79 (1.74–1.86); total body length 1.94 (1.78–2.13). Propeltidium golden-brown reticulated with iridescent white, anterior propeltidial area mottled with black; prosoma unarmed. Lateral shelves mostly iridescent white. Mesopeltidium and metapeltidium medially light golden-brown with transverse rows of iridescent white spots, laterally iridescent gold-white. First three segments of opisthosoma medially yellow-brown with iridescent white spots, median area broadening posteriorly; laterally solid gold-white, fading posteriorly, with medium brown edges medially and along boundary of segments I and II. Posterior part of opisthosoma patched white and mottled purple. Coxae I-III yellow-cream; coxae IV and venter of opisthosoma orange.

Chelicerae. Segment I 0.48 (0.36–0.57), segment II 1.09 (1.06–1.11). Iridescent white articular membranes between prosoma and chelicerae. Chelicerae white-cream reticulated with iridescent white; unarmed. Fingers long, closing tightly against each other.

Pedipalps. Femur 0.89 (0.89–0.90), patella 0.44 (0.42–0.45), tibia 0.53 (0.51–0.55), tarsus 1.09 (1.05–1.12). White-cream, unarmed. Patella with angular mediodistal bulge, but no apophysis; medial side not hypersetose. Small number of plumose setae on mediodistal end of patella only (Fig. 9d). Microtrichia along most of tarsus; claw with ventral tooth row.

Legs. Femora 3.60, 6.70 (6.46–6.93), 3.48 (3.36–3.70), 5.45 (5.13–5.94); patellae 0.88, 0.97 (0.95–0.98), 0.80 (0.75–0.85), 0.93 (0.88–0.95); tibiae 3.36, 7.40 (7.38–7.42), 3.06 (2.84–3.36), 4.91 (4.63–5.25). Trochanters medium-brown, unarmed. Legs banded medium-brown and golden-brown; legs I and III predominantly medium-brown, legs II and IV predominantly golden-brown. Femora with scattered denticles, remaining segments unarmed.

Penis (Figs 12c–d). Tendon relatively short; bristle groups well-developed. Glans of medium length; sides in ventral view subparallel, converging only slightly; dorsal side angled only slightly dorsad from shaft. Pores with surrounding rim, not raised.

Spiracle (Figs 13a–b). Sparse curtain of reticulate spines extending partway across spiracle; spines basally much broader than terminally; terminations of spines simple, pointed, some larger central spines multifurcate; dense patch of lace tubercles at lateral corner.

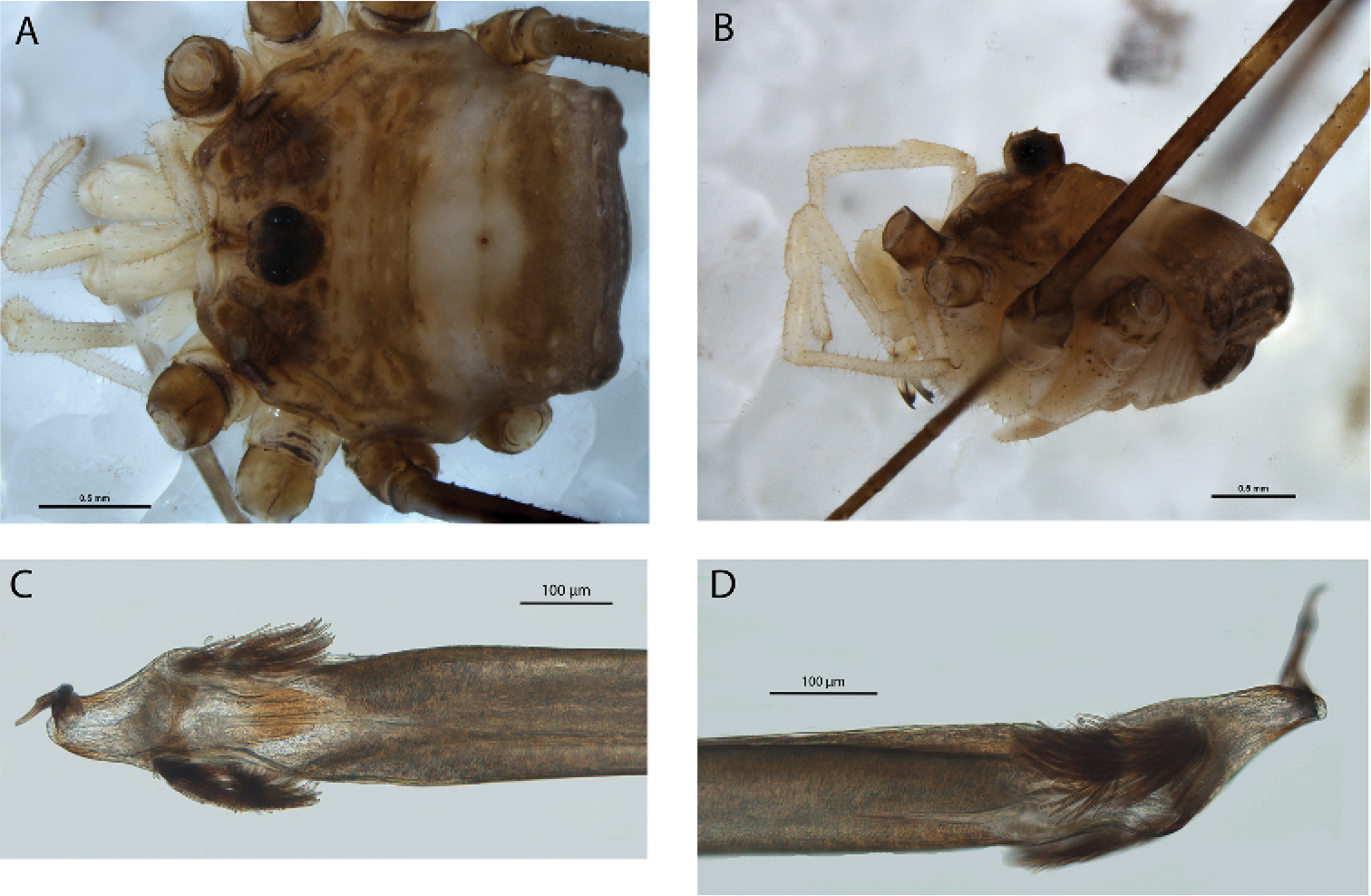

Spiracles of Megalopsalis species: a Megalopsalis coronata, spiracle b same, close-up of lateral corner c Megalopsalis puerilis, spiracle d same, close-up of lateral corner.

The paratype specimens differ in coloration from the holotype, but this may be due to preservation. QM S74237 has the prosoma golden-brown mottled with orange-brown patches, while both QM S74237 and the paratype QM S40679 have a brown transverse band, cream in the former and iridescent white in the latter, across the anterior part of the opisthosoma.

From the Latin coronatus, crowned, referring to the denticulate ocularium.

Leg I was only preserved in the holotype.

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_nigricans

Fig. 141 major male, Tasmania, Mount Wellington, 4 January 1969, J. L. Hickman, under logs (AMS KS23719); 1 major male, Tasmania, V. V. Hickman (AMS KS23737); 1 female, SW Tasmania, 12 February 1977, C. Howard, C. Johnson (AMS KS24747); 1 minor male, ditto (AMS KS24749); 2 minor males, NE Tasmania, August 1993 (QM C3.2, C5.1); 1 minor male, 1 female, SW Tasmania, Mount Rufus track, 42°07'S, 146°07'E, 29 April 1987, R. Raven, T. Churchill, open forest, pyrethrum knockdown (QM S1707).

MALE. As for

Megalopsalis nigricans: a minor male, lateral view (AMS KS24749) b penis, ventral view (AMS KS23719).

Spiracle (

This species has already been described in detail by

Despite

http://zoobank.org/6ED54D80-108C-4AFC-BB79-E9B5B92CB5E4

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_puerilis

Figs 13c–d, 15Male holotype. SE Queensland, Binna Burra, 27 March 1976, R. Raven, VED, night collection (QM S2835).

Paratype. 1 male, Springbrook Repeater, SE Queensland, 1000 m, 28°15'S, 153°16'E, 9 January–19 February 1995, G. B. Monteith, intercept traps (QM S46985).

Megalopsalis puerilis is distinguished from all other Megalopsalis species except Megalopsalis tanisphyros, Megalopsalis coronata and Megalopsalis sublucens by its small, unarmed chelicerae. It is distinguished from Megalopsalis tanisphyros by the absence of a pedipalpal patellar apophysis, from Megalopsalis coronata by the absence of denticles on the ocularium, and from Megalopsalis sublucens by the absence of ventral brush-like bristles on distitarsi III and IV. The glans of Megalopsalis puerilis is less triangular in overall shape than most other Megalopsalis species, with the sides distally subparallel in ventral view (Fig. 15c).

Megalopsalis puerilis, male (all QM S2835): a body, dorsal view b body, lateral view c glans, ventral view d glans, left ventrolateral view.

MALE (N = 2). Prosoma length 0.89 (0.83–0.94), width 1.72 (1.56–1.88); total body length 2.37 (2.35–2.38). Dorsum entirely unarmed. Anterior propeltidial area with central stripe of light orange-brown between ocularium and anterior margin of prosoma, flanked by two yellow stripes; remainder of anterior and median propeltidial areas mottled black and dark orange-brown with broad iridescent dark silver patches between ocularium and ozopores. Ocularium iridescent white with dark grey stripe down central groove. Mesopeltidium, metapeltidium and first four segments of opisthosoma orange-yellow medially and along segment boundaries with blackish brown patches laterally; fifth opisthosomal segment with transverse iridescent white stripe bordered by mottled black; remaining segments mottled black with yellow segment boundaries. Mouthparts brown-cream. Coxae dull orange proximally, mottled black distally; venter of opisthosoma iridescent white.

Chelicerae. Segment I 0.53 (0.52–0.54), segment II 1.07 (1.00–1.14). Cream; segment I with iridescent white reticulation dorsally. Both segments unarmed. Fingers long; mobile finger closes tightly with segment II.

Pedipalps. Femur 0.94 (0.90–0.97), patella 0.45 (0.44–0.45), tibia 0.58 (0.57–0.59), tarsus 1.15 (1.14–1.15). Cream; unarmed. Patella with distomedial bulge, but no true apophysis. Microtrichia on distal three-quarters of tarsus; claw with ventral tooth-comb. Legs: Femora 4.16 (3.86–4.45), 7.20 (6.08–8.31), 4.00 (3.76–4.23), 5.65 (5.10–6.19); patellae 0.91 (0.87–0.94), 1.13, 0.87 (0.84–0.89), 1.00 (0.98–1.02); tibiae 4.10 (3.64–4.55), 7.50 (6.46–8.54), 3.74 (3.46–4.02), 5.46 (4.98–5.94). Trochanters mottled black on orange, remaining segments orange-yellow, with widely-spaced mottled black transverse stripes. Femora with scattered denticles, mostly dorsal; other segments unarmed.

Penis (Figs 15c–d). Bristle groups well-developed on both sides, left groups set slightly back and longer than right groups. Glans short, sides in ventral view subparallel, dorso-ventrally flattened distally, dorsal surface in plane with shaft. Deep pores.

Spiracle (Figs 13c–d). Curtain of robust reticulate spines extending only partway across spiracle; terminations of spines multifurcate but not palmate; lace tubercles on margin of lateral corner only.

From the Latin puerilis, childish, referring to the lack of ornamentation or significant secondary sexual characteristics in the adult male.

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_stewarti

Figs 16, 18aParatypes. 1 female, Victoria, Mount Buffalo, 30–31 December 1947, ex bole of snow gum (Eucalyptus pauciflora) (NMV K-8910); 8 males, ditto (NMV K-8911–8919).

Other material examined. 1 male, Victoria, Lala Falls, near Warburton, 37°46'S, 145°42'E, 22 December 2002, M. S. Harvey, M. E. Blosfelds, under bark of Eucalyptus regnans (WAM T72315).

MALE. Description as in

Legs. Leg I with anterior longitudinal row of enlarged denticles from proximal end of femur to distal end of tibia (males with smaller chelicerae with reduced denticle row on femur only), scattered denticles on basitarsus I; smaller row on femora and patellae of other legs.

Penis (Fig. 16). Shaft and tendon elongate; all four bristle-groups well-developed. Distinct lateral protrusion of glans above left anterior bristle group. Glans short, broad, triangular in dorsal view, dorsoventrally flattened at distal end. Pores shallowly recessed.

Megalopsalis stewarti, male, glans (all WAM T72315): a ventral view b right lateral view c dorsal view.

Spiracle (Fig. 18a). Reticulate spines extending only partway across spiracle; terminations of spines palmate; small group of lace tubercles in lateral corner.

FEMALE. Description as in

Megalopsalis thryptica is very similar to Megalopsalis stewarti, from which it can be distinguished by having distitarsus IV basally swollen.

http://zoobank.org/7EAD50EE-61F4-40AB-9EFE-B6164D1596A1

http://species-id.net/wiki/Megalopsalis_sublucens

Figs 17, 18b–cMale holotype. SW Tasmania, Franklin River, below Goodwin’s Peak, January 1983, ANZSS Expedition (QM S2857).

Paratypes. 1 male, 1 female, as above (QM S2857).

Megalopsalis sublucens can be readily distinguished from other Megalopsalis species by the absence of a pedipalpal patellar apophysis or enlarged chelicerae, in combination with the presence of ventral brush-like bristles on distitarsi III and IV. It can also be distinguished from other species except Megalopsalis stewarti by the presence of a lateral protrusion on the left side of the glans near the shaft-glans junction (Fig. 17c).

Megalopsalis sublucens, male (all QM S2857): a body, dorsal view b body, lateral view c glans, ventral view d glans, left ventrolateral view.

MALE (N = 2). Prosoma length 1.34 (1.33–1.34), width 1.99 (1.98–2.00); total body length 2.66 (2.59–2.72). Dorsum entirely unarmed. Dark tan stripes from ocularium to anterior margin, remainder of anterior iridescent white. Median propeltidial area white with dark brown patches. Posterior propeltidial area mottled dark brown. Lateral shelves dark brown anteriorly, iridescent white around and posterior to ozopores. Ocularium golden-brown with anterior face silver. Mesopeltidium, metapeltidium and first four segments of opisthosoma medially yellow-brown edged with dark brown with medial iridescent white spots; laterally iridescent white with dark purple mottling. Posterior of opisthosoma white with purple mottling. Venter of prosoma cream, coxae mottled black distally; opisthosoma purple-brown with transverse rows of iridescent white spots.

Chelicerae. Segment I 0.68, segment II 1.65 (1.57–1.73). Yellow-cream with tan mottling; not particularly enlarged compared to female. Segment I unarmed, segment II with proximodorsal denticles only. Fingers long, apotele closely opposed to finger of segment II.

Pedipalp. Femur 1.13 (1.11–1.15), patella 0.54 (0.50–0.58), tibia 0.70, tarsus 1.35 (1.32–1.38). Banded dark brown and yellow-brown; unarmed; no apophyses. Tooth-comb on apotele.

Legs. Femora 3.50 (3.42–3.58), 6.26 (6.13–6.38), 3.28, 5.44 (5.19–5.69); patellae 1.17 (1.13–1.20), 1.27, 1.02, 1.13 (1.06–1.20); tibiae 3.15 (3.07–3.22), 5.48, 3.08, 4.70 (4.50–4.90). Banded dark brown and yellow-brown, with prominent iridescent white spots around accessory spiracles on tibiae. No denticles, but robust spinose setae on all legs to tibiae. Brush-like bristles intermittently present on ventral side of distitarsi III and IV. Femur II not pseudosegmented, tibia II with six pseudosegments, tibia IV with two pseudosegments.

Penis (Figs 17c–d). Left anterior bristle group reduced, but left posterior group well-developed. Glans short, triangular in dorsal view, dorsoventrally flattened, dorsal edge in plane with shaft.

Spiracle (Figs 18b–c). Sparse spines, reticulate basally with reticulations fading terminally, extending across spiracle; terminations of spines palmate, anastomosing; no lateral lace tubercles.

FEMALE (N = 1). Prosoma length 1.40, width 2.03; total body length 4.45. As for male except for following. Ocularium iridescent white. Venter of opisthosoma duller.

Spiracles of Megalopsalis species: a Megalopsalis stewarti, lateral corner b Megalopsalis sublucens, lateral corner c same, showing anastomosing ends of median spines.

Chelicerae. Segment I 0.75, segment II 1.32. Unarmed.

Pedipalps. Femur 1.01, patella 0.50, tibia 0.64, tarsus 1.27.

Legs. Femora 2.32, 4.45, 2.28, 3.56; patellae 0.82, 1.01, 0.93, 0.95; tibiae 2.43, 4.30, 2.35, 3.44. Tibia IV undivided.

From the Latin sublucens, gleaming faintly, in reference to the iridescent patches covering part of the dorsum.

Those measurements for which a range is not given in the description of the male were only preserved in the holotype.

While Megalopsalis sublucens possesses brush-like bristles on distitarsi III and IV as found in Megalopsalis stewarti, Megalopsalis tasmanica and species of the Megalopsalis serritarsus-group, the number of bristles is reduced and they are proportionately more widely spaced and less regular. This may be related to Megalopsalis sublucens’ smaller size.

A maximum parsimony analysis was conducted using the programme TNT (

- Elongate anterior propeltidial area, sloping downwards anteriorly: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Ozopore position: (0) flush with lateral margin of prosoma; (1) raised on protruding lobes.

- Ozopore shape: (0) small and circular; (1) large and oval or oblong.

- Raised humps on either side of ocularium: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Raised postocularial hump: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Mesopeltidium: (0) distinct; (1) merged with propeltidium.

- Position of anterior margin of mesopeltidium relative to ocularium: (0) mesopeltidium immediately behind ocularium; (1) distinct space between ocularium and anterior margin of mesopeltidium.

- Metapeltidium: (0) non-sclerotised; (1) sclerotised.

- Dorsal junction between prosoma and opisthosoma: (0) free; (1) fused.

- Dorsum of opisthosoma: (0) non-sclerotised; (1) sclerotised.

- Penis tendon: (0) long; (1) short.

- Angular ventral junction between shaft and glans: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Lateral processes behind shaft-glans articulation: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Bristle groups as lateral processes of penis: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Asymmetry of penis bristle groups: (0) both sides present; (1) left bristle groups absent in ventral view.

- Fused base of lateral bristles on penis: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Dorsal edge of glans: (0) in same plane as shaft; (1) directed dorsad relative to shaft.

- Lateral extension on left side of glans: (0) absent; (1) present. In Megalopsalis stewarti and Megalopsalis sublucens, the left side of the glans protrudes outwards above the anterior bristle group (Figs 16c, 17d).

- Setae or bristles on glans: (0) absent; (1) single lateral setae; (2) numerous setae or bristles.

- Deeply recessed pores on glans: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Raised pore-bearing papillae on glans: (0) absent; (1) present. These last two characters were treated as separate states of a single character in

Taylor (2011 ; character 25 therein). This was probably inappropriate: there is no a priori reason to believe that a single species could not possess both pore morphologies, and they are here treated separately.Taylor (2011) also differentiated character states for shallowly recessed or shallowly raised genital pores; upon re-examination of the electron micrographs used in coding these states, I am not convinced that they are not artefactual (possibly related to the preservation of the specimen used). I have therefore not included these states in the current analysis. - Glans length: (0) short; (1) long.

- Glans depth: (0) shallow in lateral view; (1) distinctly deep. In Pantopsalis albipalpis, the glans is surmounted by a relatively high, narrow dorsal keel, but the main body of the glans is still recognisable a narrow triangular shape in lateral view, contrasting with the more uniformly deep glans in Tercentenarium linnaei (

Taylor 2008b ) and Australiscutum species (Taylor 2009 ). Pantopsalis albipalpis is therefore coded as lacking this character. - Glans shape in ventral view: (0) subtriangular; (1) parabolic; (2) narrow or constricted. This character replaces character 19 in

Taylor (2011) , in which the alternate character states were poorly distinguished. A subtriangular glans characterises the species discussed in the current paper (as well as those attributed to Megalopsalis inTaylor 2011 ), in which the sides converge along the greater length of the relatively broad glans. Species of genera such as Pantopsalis (Taylor 2004 ,2013 ) and Australiscutum (Taylor 2009 ) have a parabolic glans shape, in which the glans is relatively longer and the rate of convergence of the sides less rapid. Species of outgroup taxa such as Ballarrinae (Hunt and Cokendolpher 1991 ), as well as Monoscutum titirangiense (Taylor 2008a ) have a very narrow, elongate glans. - Central concavity on ventral face of glans: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Dorsal side of glans basally inflated: (0) absent; (1) present (e.g. Figs 3e, 4e).

- Shape of distal end of glans: (0) not dorsoventrally flattened; (1) distinctly dorsoventrally flattened.

- Protruding distal end of glans: (0) absent; (1) present. In species exhibiting this character, the glans is essentially subtriangular in overall shape, but the distal end of the glans has become extended, with the lateral margins becoming more subparallel distally after converging in the proximal part of the glans (Figs 10d, 15c).

- Triangular dorsolateral keel on glans: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Sharp dorsal papillae on glans: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Longitudinal membrane on stylus: (0) absent; (1) present; (2) enlarged. Species of Neopilionidae have a longitudinal membranous banner running along the stylus, and often wrapped around it. This membrane has become particularly large in Australiscutum. Ballarra longipalpus is coded as lacking this character, though its presence in Americovibone lanfrancoae suggests its absence may be secondary for the former species; small membranous flanges at the base of the stylus in Ballarra species (

Hunt and Cokendolpher 1991 ) may represent the remnants of a reduced banner. - Number of seminal receptacles: (0) two; (1) four.

- Microsculpture anterior to spiracle: (0) unornamented; (1) ornamented.

- Spiracular entapophysis: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Anterior spines at spiracular aperture: (0) absent; (1) Dyspnoi-form spines; (2) Thrasychirus-form spines or lace tubercles. This character has not been treated as additive. See

Taylor (2011) for a discussion of the potential homology or otherwise between the spiracular spines present in Enantiobuninae and those present in Dyspnoi and Caddo. Ballarra longipalpus was coded byTaylor (2011) as exhibiting a fourth state of this character; however, as illustrated byTaylor (2011 : fig. 15), the spiracular spines of Ballarra longipalpus are derived from hypertrophy of the micro-ornamentation covering the broader venter, and are almost certainly not directly homologous with the spines present in Enantiobuninae, which are restricted to the spiracle and differ from the surrounding micro-ornamentation. The character state ‘Ballarra-form spines’ has therefore been removed from the current analysis, and Ballarra longipalpus has been coded as lacking this character. Neopilio australis, previously coded as unknown for this character, has been re-coded as possessing Thrasychirus-form spines on the basis of the figure provided byHunt and Cokendolpher (1991) . - Reticulate anterior spiracular spines: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Extent of anterior spines over spiracle: (0) absent; (1) halfway; (2) entire spiracle.

- Terminations of anterior spiracular spines: (0) simple; (1) palmate.

- Lace tubercles at corner of spiracle: (0) absent; (1) present. Megalopsalis suffugiens possesses a patch of lace-like reticulation marking the position occupied by the lace tubercles in other taxa, and has been coded as possessing this character.

- Posterior margin of spiracle: (0) unornamented; (1) short ornamentation; (2) elongate spines.

- Ventral spur at base of cheliceral segment I: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Ventrolateral row of enlarged denticles on cheliceral segment I: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Cheliceral segment II compared to segment I: (0) not significantly inflated; (1) inflated.

- Cheliceral finger length: (0) short; (1) long.

- Mobile finger of chelicera: (0) closes tightly against immobile finger of segment II; (1) bows away from immobile finger proximally.

- Setae on mobile finger of chelicera: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Medial side of pedipalpal coxae: (0) unarmed; (1) with covering of blunt denticles.

- Plumose setae on pedipalp: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Length of pedipalpal femur: (0) shorter than or subequal to prosoma length; (1) more than 1.5 × as long as prosoma.

- Pedipalpal patella vs tibia: (0) patella shorter than tibia; (1) patella longer than tibia.

- Medial side of pedipalpal patella: (0) sparsely setose; (1) hypersetose.

- Apophysis on pedipalpal patella: (0) absent; (1) poorly developed (less than one-third of patella length); (2) well-developed (about one-half of patella length). In

Taylor (2011) , the presence of a pedipalpal patellar apophysis was coded separately for males and females; this risked inappropriately weighting the significance of the patellar apophysis as the two characters are closely correlated. Instead, the presence of a pedipalpal patellar apophysis has here been coded as a single character, with a second character (character 53 below) coded only for species possessing the apophysis to account for the reduction of the apophysis in the male of Pantopsalis species relative to the females. - Pedipalpal patellar apophysis in male: (0) reduced relative to female apophysis; (1) fully developed as in female.

- Shape of apophysis on pedipalpal patella: (0) rounded; (1) triangular. As with character 52, this character has been coded for both males and females rather than the two being coded separately as in

Taylor (2011) . The only species in which males and females are known to differ in apophysis shape, Forsteropsalis grimmetti, has been coded as polymorphic for this character. - Pedipalp with reflexed tibia relative to patella: (0) absent; (1) present. A dorsally reflexed pedipalpal tibia is characteristic of the Ballarrinae (

Hunt and Cokendolpher 1991 ). - Shape of pedipalpal tibia: (0) straight; (1) bent mediad from patella.

- Distribution of microtrichia on pedipalp: (0) absent; (1) distal half to third of tarsus only; (2) full length of tarsus; (3) tibia and tarsus.

- Pedipalpal claw: (0) reduced or absent; (1) present. Neopilio australis has been coded as possessing a reduced pedipalpal claw, as per

Hunt and Cokendolpher (1991) . - Teeth on pedipalpal claw: (0) absent or only one or two teeth; (1) tooth-comb.

- Armature of coxa I: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Armature of trochanter I: (0) absent; (1) present in the form of prolateral denticles only; (2) present in the form of prolateral and retrolateral denticles; (3) present in the form of retrolateral denticles only. This character has not been treated as additive.

- Leg I length and shape: (0) long and slender; (1) short and sturdy.

- Leg I armature in male: (0) absent; (1) present on femur; (2) present on femur to patella; (3) present on femur to tibia; (4) present on femur to basitarsus; (5) present on femur to distitarsus.

- Arrangement of denticles on leg I: (0) scattered; (1) sublinear; (2) linear.

- Prolateral longitudinal row of hypertrophied spines on leg I: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Pseudoarticulations in femur II: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Accessory tracheal stigmata in tibiae: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Tibia II shape: (0) cylindrical; (1) swollen.

- Pseudoarticulations in tibia II: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Pseudoarticulations in tibia IV: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Pseudoarticulations in basitarsi: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Ventrodistal spines on basitarsal pseudosegments: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Mobile hinge between basitarsus and distitarsus: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Ventrodistal spines on the junction of the basitarsus and distitarsus: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Ventrodistal swelling on pseudosegments of distitarsus II: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Ventral double row of brush-like bristles on distitarsi III and IV: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Ventrodistal spines on distitarsal pseudosegments: (0) absent; (1) present.

- Proximal part of distitarsi III and IV: (0) not swollen; (1) swollen.

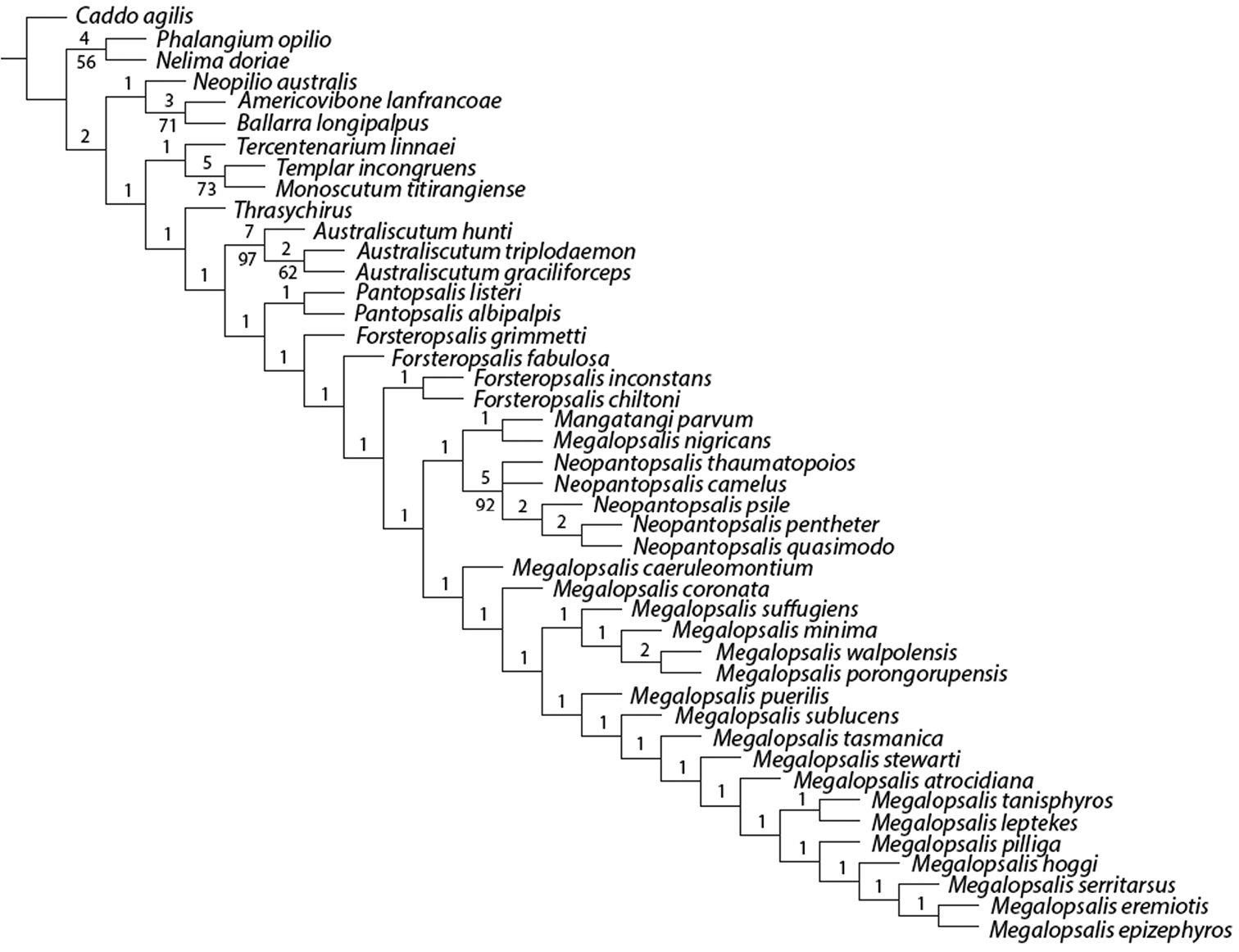

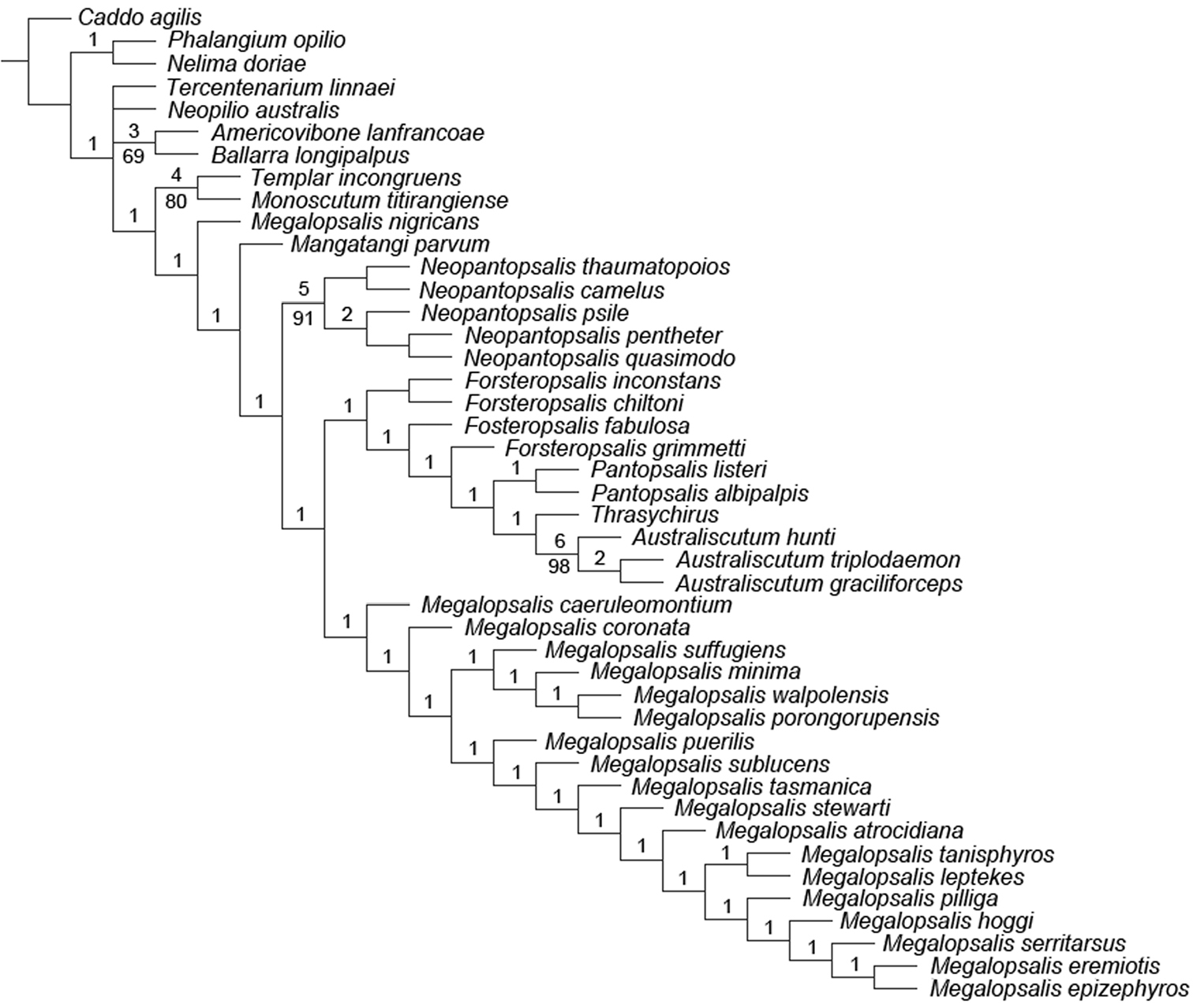

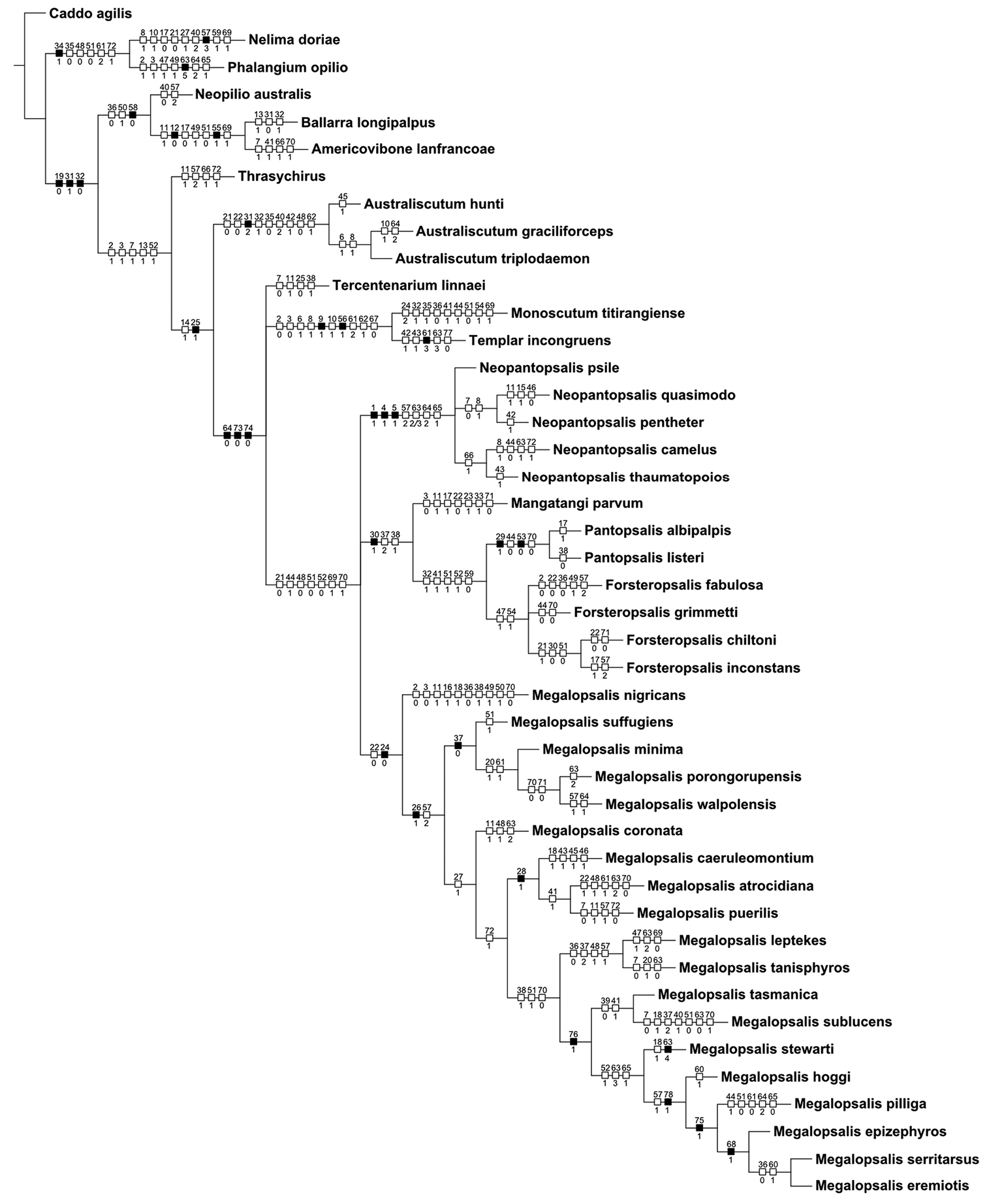

The analysis with all characters given equal weight, and multistate characters treated as ordered, produced two equally supported trees of 321 steps (CI = 0.290, RI = 0.626), the consensus of which is shown in Fig. 19. Bremer support for most clades was low, and very few can be regarded as numerically well supported. Nevertheless, monophyly was recovered for Neopilionidae (including Ballarrinae) and Enantiobuninae sensu

Consensus from equal weights analysis with multistate characters ordered. Numbers above branches indicate Bremer support values; numbers below branches indicate jack-knife support. Those branches without lower numbers received less than 50% jack-knife support.

50% majority rule consensus of trees resulting from equal and implied weights analyses with multistate characters ordered. Numbers on branches indicate percentage of trees in which the given clade was recovered.

Plot of recovery for selected clades under varying weight analyses with ordered characters. Gray fill indicates monophyly; white fill indicates para- or polyphyly. Abbreviations used: Mang. = Mangatangi; Pant. = Pantopsalis; Forst. = Forsteropsalis; M. = Megalopsalis. See text for definition of Megalopsalis minima- and Megalopsalis serritarsus-groups.

| k value | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neopilionidae | |||||||

| Enantiobuninae | |||||||

| Australasian Enantiobuninae | |||||||

| Australiscutum | |||||||

| Mang. + Pant. + Forst. | |||||||

| Pantopsalis + Forsteropsalis | |||||||

| Pantopsalis | |||||||

| Forsteropsalis | |||||||

| Neopantopsalis | |||||||

| Megalopsalis | |||||||

| Megalopsalis excl. M. nigricans | |||||||

| M. minima-group | |||||||

| M. serritarsus-group |

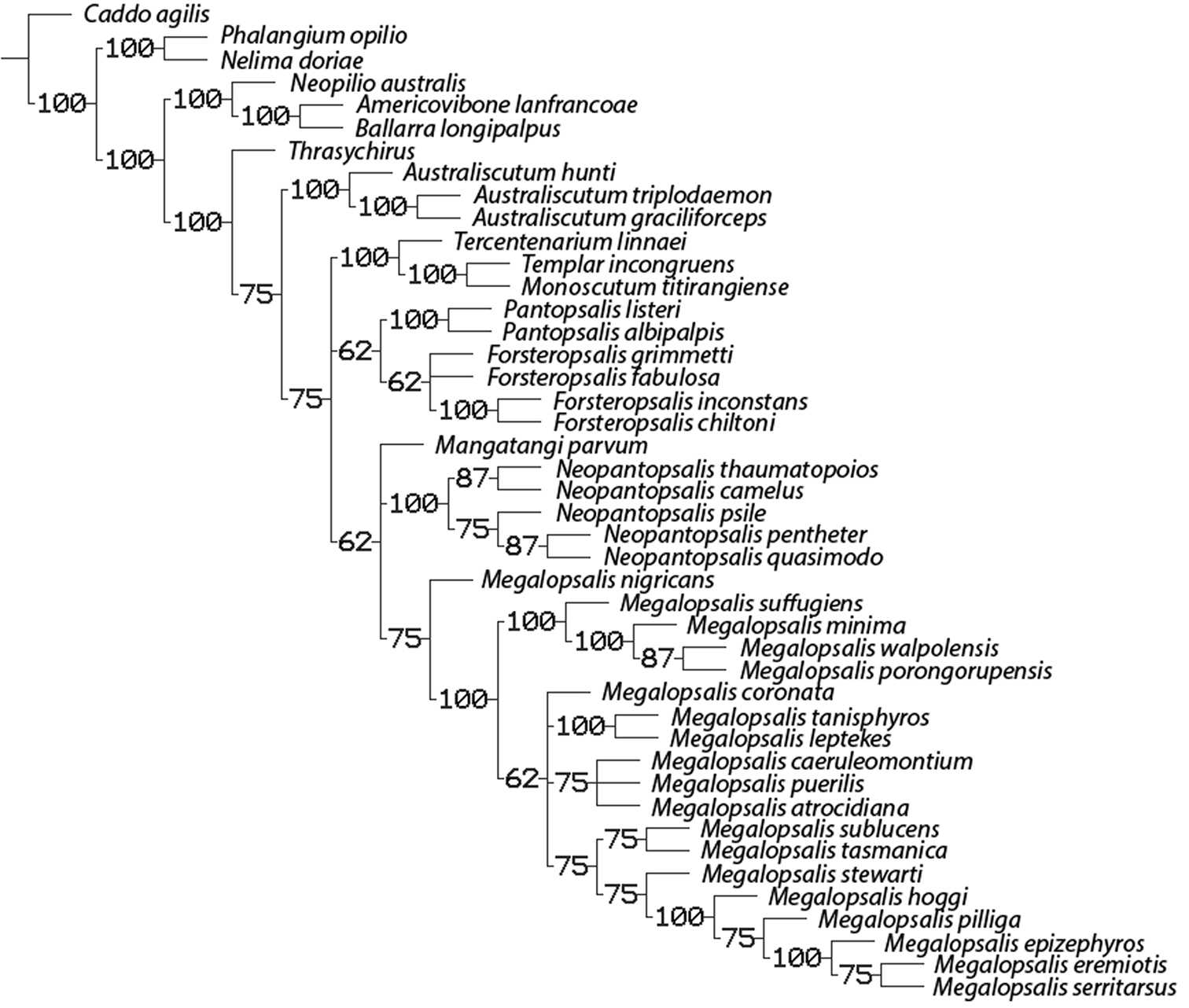

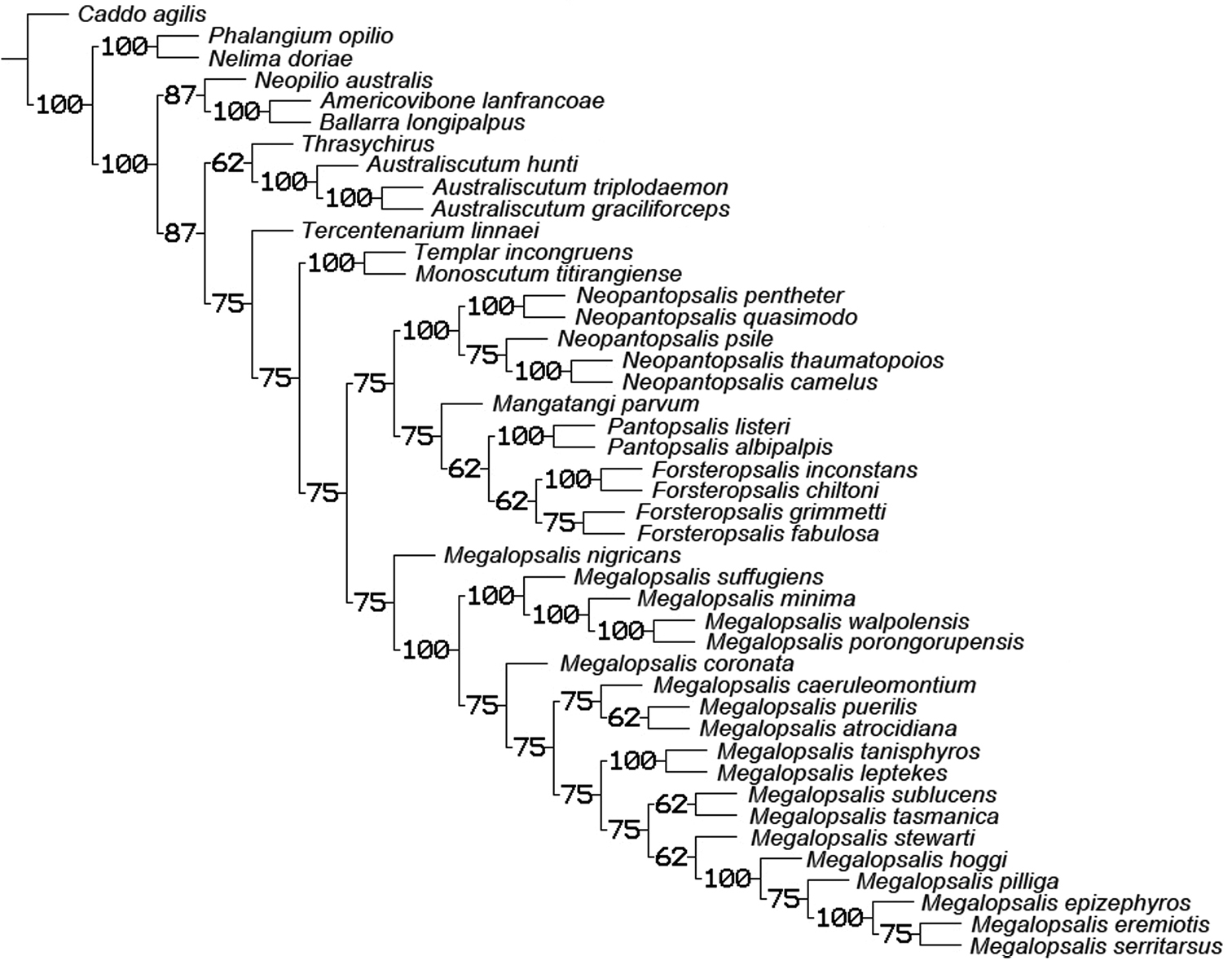

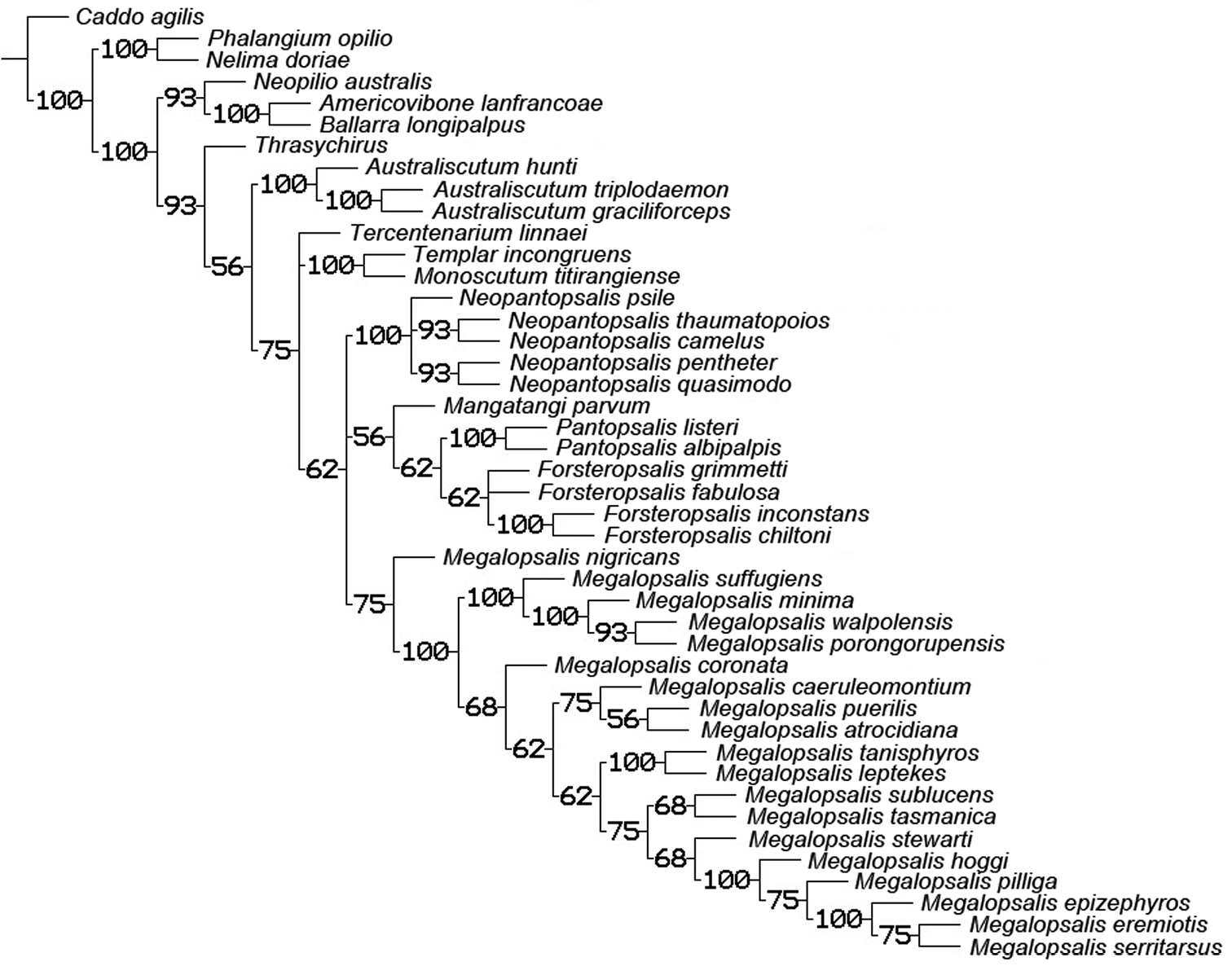

A second round of analyses was also conducted with multistate characters treated as unordered. When all characters were given equal weight, this analysis produced two equally supported trees of 309 steps (CI = 0.301, RI = 0.633), the consensus of which is shown in Fig. 21. Though Neopilionidae was recovered as monophyletic in both trees, Enantiobuninae was only recovered in one tree, in which Neopilio australis and Ballarrinae were sister taxa as in the analyses with ordered characters. In the other best tree, Neopilio australis alone was sister to the remaining Neopilionidae, while Tercentenarium linnaei was placed outside a clade of Ballarrinae and the remaining Enantiobuninae. All implied weights analyses with unordered characters recovered a single best tree in which both Neopilionidae and Enantiobuninae were monophyletic. Figure 22 shows the majority-rule consensus for all analyses with unordered characters, with support for selected clades under individual weighting schemes shown in Table 2. Figure 23 shows the strict consensus of clades recovered under all analytical conditions, with a total majority-rule consensus shown in Fig. 24. Figure 25 shows the distribution of apomorphies when mapped onto the consensus tree in Fig. 24; some of these apomorphies are discussed below.

Consensus from equal weights analysis with multistate characters unordered. Numbers above branches indicate Bremer support values; numbers below branches indicate jack-knife support. Those branches without lower numbers received less than 50% jack-knife support.

50% majority rule consensus of trees resulting from equal and implied weights analyses with multistate characters unordered. Numbers on branches indicate percentage of trees in which the given clade was recovered.

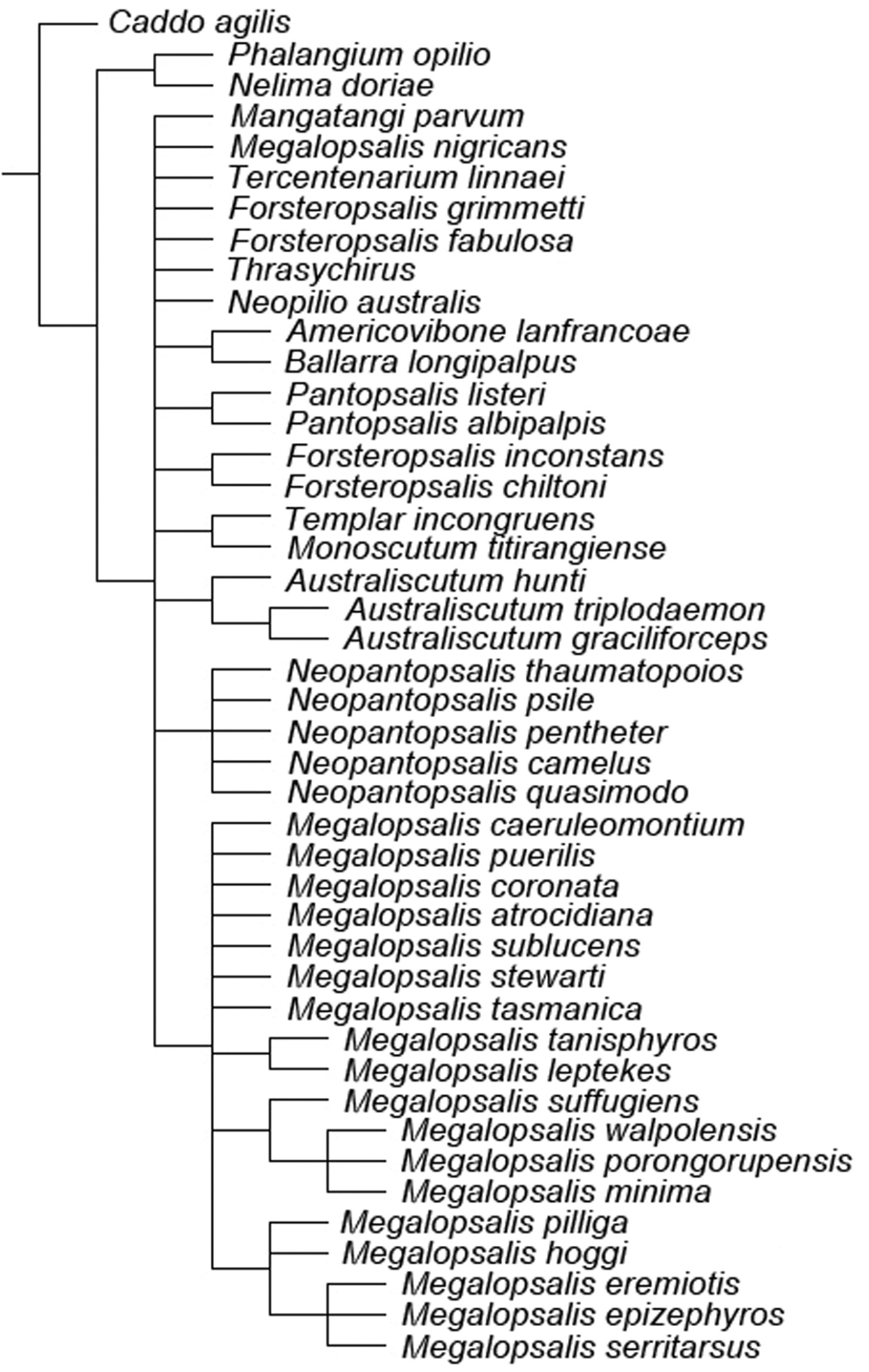

Strict consensus of all trees recovered under all analytical conditions.

50% majority rule consensus of all trees resulting from all analyses. Numbers on branches indicate percentage of trees in which the given clade was recovered.

Plot of recovery for selected clades under varying weight analyses with unordered characters. Grey fill indicates monophyly; black fill indicates monophyly in only one of two best trees; white fill indicates para- or polyphyly. Abbreviations as for Table 1.

| k value | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neopilionidae | |||||||

| Enantiobuninae | |||||||

| Australasian Enantiobuninae | |||||||

| Australiscutum | |||||||

| Mang. + Pant. + Forst. | |||||||

| Pantopsalis + Forsteropsalis | |||||||

| Pantopsalis | |||||||

| Forsteropsalis | |||||||

| Neopantopsalis | |||||||

| Megalopsalis | |||||||

| Megalopsalis excl. M. nigricans | |||||||

| M. minima-group | |||||||

| M. serritarsus-group |

Neopilionidae is potentially supported by the absence of setae on the glans itself (char. 19), and by the presence of a longitudinal banner on the stylus (char. 31: lost within Ballarrinae, unknown for Thrasychirus). Reduction of the number of seminal receptacles to two (char. 32) is also mapped as a potential synapomorphy, but this character is reversed in Australiscutum and Pantopsalis + Forsteropsalis. Within Neopilionidae, most analyses supported a basal split between Enantiobuninae on one side and Neopilio + Ballarrinae on the other. The relationship between the latter two taxa is supported by one unique synapomorphy, the reduction in the pedipalpal claw (char. 58;

The current analysis is, admittedly, limited in its ability to test neopilionid monophyly by the low number of outgroup taxa included. Members of all other families of Phalangioidea possess setae on the glans (

Many of the relationships within the Enantiobuninae are sensitive to weighting regimes, but the results are more stable than those found by

For the most part, the remaining relationships between genera in Enantiobuninae were not robust to analytical conditions. Analyses with multistate characters ordered supported a relationship between Tercentenarium and the Monoscutum clade, but this was not supported when multistate characters were unordered. Most analyses placed these taxa towards the base of the enantiobunines, which accords with their morphological distinctiveness. The New Zealand Templar incongruens and Monoscutum titirangiense (together with Acihasta salebrosa, not included in the current analysis but expected to be closely related to these two taxa) are short-legged, heavily sclerotised species previously classified as their own subfamily Monoscutinae (

Implied weights analyses supported a relationship between the New Zealand genera Pantopsalis and Forsteropsalis as found by

Neopantopsalis was supported as monophyletic in all analyses, though its internal topology was sensitive to analysis conditions. Varying analyses placed it closer to either Megalopsalis or Pantopsalis + Forsteropsalis.

As found by

Spinicrus and Megalopsalis were distinguished by the presence in the latter of a lateral apophysis on the patella of the pedipalp (

For the most part, this expanded Megalopsalis forms a distinct clade in all analyses. The only exception is Megalopsalis nigricans, which is placed as the basalmost species of Megalopsalis in the implied weights analyses but does not form a clade with Megalopsalis in the equal weights analyses. The glans of Megalopsalis nigricans lacks the bellied profile of other Megalopsalis species, and is less regularly subtriangular than most other species. Megalopsalis nigricans also possesses a distinctly short and broad shaft to the penis compared to the relatively elongate and narrow shaft of other Megalopsalis species (Fig. 14b). Nevertheless, Megalopsalis nigricans is more similar in genital morphology to Megalopsalis speciesthan to other Enantiobuninae. Compared to other species of Enantiobuninae, Megalopsalis nigricans is a particularly small taxon with reduced armature, and it is possible that its position is being distorted in the equal weights analyses by homoplasy with similarly small-bodied taxa such as Mangatangi parvum. Rather than creating a new monotypic genus for this species, Megalopsalis nigricans is here provisionally assigned to Megalopsalis.