(C) 2013 Kristofer M. Helgen. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Helgen KM, Pinto CM, Kays R, Helgen LE, Tsuchiya MTN, Quinn A, Wilson DE, Maldonado JE (2013) Taxonomic revision of the olingos (Bassaricyon), with description of a new species, the Olinguito. ZooKeys 324: 1–83. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.324.5827

We present the first comprehensive taxonomic revision and review the biology of the olingos, the endemic Neotropical procyonid genus Bassaricyon, based on most specimens available in museums, and with data derived from anatomy, morphometrics, mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, field observations, and geographic range modeling. Species of Bassaricyon are primarily forest-living, arboreal, nocturnal, frugivorous, and solitary, and have one young at a time. We demonstrate that four olingo species can be recognized, including a Central American species (Bassaricyon gabbii), lowland species with eastern, cis-Andean (Bassaricyon alleni) and western, trans-Andean (Bassaricyon medius) distributions, and a species endemic to cloud forests in the Andes. The oldest evolutionary divergence in the genus is between this last species, endemic to the Andes of Colombia and Ecuador, and all other species, which occur in lower elevation habitats. Surprisingly, this Andean endemic species, which we call the Olinguito, has never been previously described; it represents a new species in the order Carnivora and is the smallest living member of the family Procyonidae. We report on the biology of this new species based on information from museum specimens, niche modeling, and fieldwork in western Ecuador, and describe four Olinguito subspecies based on morphological distinctions across different regions of the Northern Andes.

Andes, Bassaricyon, biogeography, Neotropics, new species, olingo, Olinguito

“New Carnivores of any sort are always few and far between…”

Oldfield Thomas (1894:524)

Olingos (genus Bassaricyon J.A. Allen, 1876) are small to medium-sized (0.7 to 2 kg) arboreal procyonids found in the forests of Central America and northern South America. No comprehensive systematic revision of the genus has ever been undertaken, such that species boundaries in Bassaricyon are entirely unclear, and probably more poorly resolved than in any other extant carnivoran genus. There are various reasons for limited knowledge of Bassaricyon. For such a widespread genus of Carnivora, olingos were discovered surprisingly late (first described from Central America in 1876 and from South America in 1880;

Here we review the taxonomic standing of all named forms of Bassaricyon based on morphological, morphometric, and molecular comparisons of voucher specimens in museums; we clarify the distribution and conservation status of each valid taxon; and, as far as possible, we enable information from published literature on olingo anatomy (e.g., Beddard 1900,

All previously described olingo taxa occur in lower to middle-elevation tropical or subtropical forests (≤ 2000 meters in elevation). Remarkably, our morphological, morphometric, molecular, and field studies document the existence of an undescribed species in the genus, endemic to higher-elevation cloud forests (1500 to 2750 meters) in the Western and Central Andes of Colombia and Ecuador, which we describe here as a new species. (This species has been discussed preliminarily, in advance of its formal description, by

We examined all Bassaricyon specimens in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA (AMNH); Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, USA (ANSP); Natural History Museum, London, UK (BMNH); Museo de Zoología, Universidad Politecnica, Quito, Ecuador (EPN); Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, USA (FMNH); Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence, USA (KU); Los Angeles County Natural History Museum, Los Angeles, USA (LACM); Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA (MCZ); Museo Ecuatoriano de Ciencias Naturales, Quito, Ecuador (MECN); Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, USA (MVZ); Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm, Sweden (NMS); Museo de Zoología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador (QCAZ); Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada (ROM); Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections, Texas A&M University, College Station, USA (TCWC); Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA (UMMZ); National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA (USNM); Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, USA (YPM); and Museum für Naturkunde, Humboldt Universität, Berlin, Germany (ZMB). These holdings include all type specimens in the genus and represent the great majority (well over 95%) of olingo specimens in world museums. We also had access to published information on a few additional specimens in museum collections in Colombia and Bolivia (

List of samples (and associated information) used in phylogenetic analysis. Boldfaced entries represent samples newly sequenced in this study.

| SPECIES | Identifier in Figure 1 | Specific locality | Source (catalog reference) | Genbank Accession Numbers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome b | CHRNA1 | ||||

| Bassaricyon medius orinomus | Panama | Limbo plot | NYSM ZT105 | EF107703 | KC773757 |

| Bassaricyon medius orinomus | Panama | Rio Juan Grande | NYSM ZT106 | EF107704 | KC773758 |

| Bassaricyon medius orinomus | Panama | Limbo plot | Koepfli et al. (2007) | DQ660300 | DQ660210 |

| Bassaricyon medius medius | Ecuador | Las Pampas | QCAZ 8659; tk149097 | EF107706 | KC773759 |

| Bassaricyon medius medius | Ecuador | Las Pampas | QCAZ 8658; tk149094 | EF107707 | KC773760 |

| Bassaricyon alleni | Guyana | Iwokrama | ROM 107380 | EF107710 | KC773763 |

| Bassaricyon alleni | Peru | Rio Cenapa | MVZ 155219; Koepfli et al. (2007) | DQ660299 | DQ660209 |

| Bassaricyon gabbii | Costa Rica | Monteverde | KU 165554 | JX948744 | --- |

| Bassaricyon neblina neblina | Ecuador | La Cantera | QCAZ 8662; tk149108 | EF107708 | KC773761 |

| Bassaricyon neblina neblina | Ecuador | Otonga Reserve | QCAZ 8661; tk149001 | EF107709 | KC773762 |

| Bassaricyon neblina osborni | Colombia | Vicinity of Cali | Genbank | X94931 | DQ533950 |

| Potos flavus | Potos flavus | Costa Rica |

|

DQ660304 | DQ660214 |

| Procyon cancrivorus | Procyon cancrivorus | Paraguay |

|

DQ660305 | DQ660215 |

| Procyon lotor | Procyon lotor | Montana, USA |

|

DQ660306 | AF498152 |

| Bassariscus astutus | Bassariscus astutus | Arizona, USA |

|

AF498159 | AF498151 |

| Bassariscus sumichrasti | Bassariscus sumichrasti | Mexico |

|

DQ660301 | DQ660211 |

| Nasua nasua | Nasua nasua | Bolivia |

|

DQ660303 | DQ660213 |

| Nasua narica | Nasua narica | Panama |

|

DQ660302 | DQ660212 |

| Enhydra lutris | Mustelidae | Attu Island, Alaska, USA |

|

AF057120 | AF498131 |

| Eira barbara | Mustelidae | Bolivia |

|

AF498154 | AF498144 |

| Taxidea taxus | Mustelidae | New Mexico, USA |

|

AF057132 | AF498148 |

| Neovison vison | Mustelidae | Texas, USA |

|

AF057129 | AF498140 |

| Martes americana | Mustelidae | Rocky Mtn Research Station, USA |

|

AF057130.1 | AF498141 |

| Lontra longicaudis | Mustelidae | Kagka, Peru |

|

AF057123.1 | AF498134 |

| Ictonyx libyca | Mustelidae | Brookfield Zoo | Genbank | EF987739.1 | EF987699 |

| Meles meles | Mustelidae | No voucher infromation |

|

AM711900.1 | AF498147 |

| Mephitis mephitis | Mephitidae | San Diego Zoo |

|

HM106332.1 | GU931029.1 |

| Spilogale putorius | Mephitidae |

|

NC_010497.1 | GU931030.1 | |

| Ailurus fulgens | Ailuridae |

|

AM711897.1 | GU931037.1 | |

| Arctocephalus australis | Otariidae |

|

AY377329.1 | DQ205738.1 | |

| Odobenus rosmarus | Odobenidae |

|

GU174611.1 | DQ093076.1 | |

| Phoca fasciata | Phocidae |

|

GU167294.1 | GU167764.1 | |

| Mirounga angustirostris | Phocidae |

|

AY377325.1 | DQ093075.1 | |

| Canis lupus | Canis lupus |

|

AY598499 | DQ205757 | |

| Nyctereutes procyonoides | other Canidae |

|

GU256221 | GU931027.1 | |

| Urocyon cinereoargenteus | other Canidae |

|

JF489121.1 | GU931028.1 | |

| Ailuropoda melanoleuca | Ursidae |

|

NC_009492 | DQ093074.1 | |

| Ursus americanus | Ursidae |

|

NC_003426.1 | DQ205726.1 | |

Values from external measurements of 95 specimens are presented to provide an appreciation of general body size and lengths and proportions of appendages. Values (in mm) for total length and length of tail are those recorded by collectors on labels attached to skins; subtracting length of tail (abbreviated TV) from total length produced a value for length of head and body (HB). Values for length of hind foot (HF), which includes claws, were either obtained from skin labels or from our measurements of dry study skins; those for length of external ear (E), or pinna, come from collector’s measurements recorded on skin labels or in field journals (we assume, but are not certain for all specimens, that ear-length measurements represent the greatest length from the notch to the distal margin of the pinna).

Morphological terminology follows

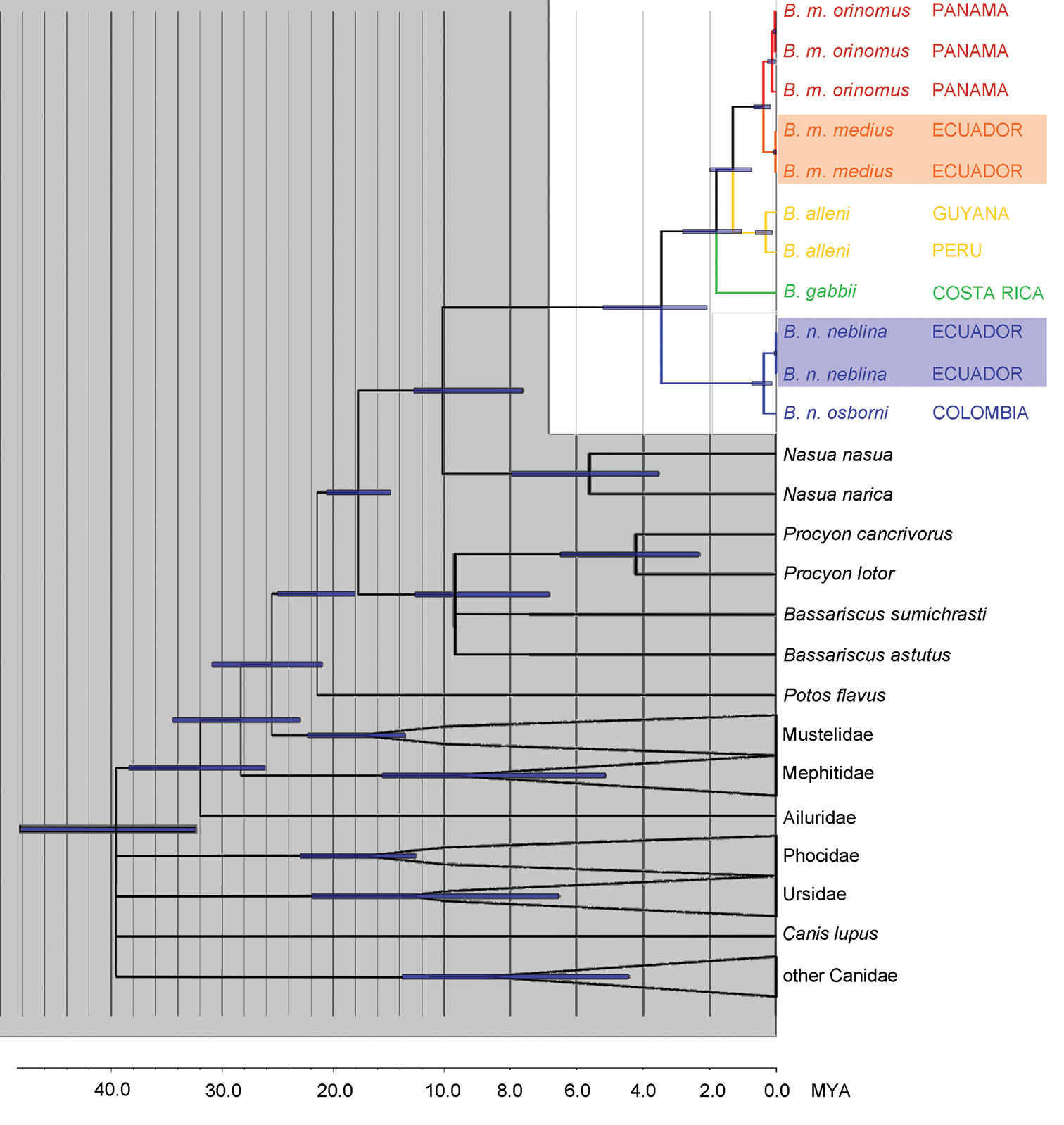

The taxa and sequences included in our analysis are listed in Table 1. Our choice of taxa outside of Bassaricyon was guided by the findings of

Tissues from fresh and frozen specimens were processed using a Qiagen DNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) to obtain genomic DNA. The sample from the skull of KU 165554, a museum specimen of Bassaricyon gabbii, was taken from the turbinate bones and extracted following the method of

Mitochondrial gene, cytochrome b: For cytochrome b (1140 bp), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing reactions were carried out with primers LGL 765 and LGL 766 from

Nuclear intron, Cholinergic Receptor Nicotinic Alpha Polypeptide 1 precursor (CHRNA1): For CHRNA1 (347 bp), we used the primers described by

Each PCR was conducted with negative and positive controls to minimize risk of spurious results from contamination or failure of the reaction. A 2μL sample of the PCR product was stained with ethidium bromide and run on an agarose gel with a 1 kb ladder. The gel was placed under UV light to visualize the PCR products. Polymerase chain reaction products were amplified for sequencing using a 10 μL reaction mixture of 2 μL of PCR product, 0.8 μL of primer (10 μM), 1.5 μL Big Dye 5 x Buffer (Applied Biosystems), 1 μL Big Dye version 3 (Applied Biosystems), and 4.7 μL sterile water. The reaction was run using a thermal cycler (MJ Research) with denaturation at 96°C for 10 s, annealing at 50°C for 10 s and extension at 60°C for 4 min: this was repeated for 25 cycles. The product was cleaned using sephadex filtration method and sequences for both strands were run on a 50 cm array using the ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Sequences were aligned and edited in Sequencher version 4.1.2 using the implemented Clustal algorithm and the default gap penalty parameters (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, http://www.genecodes.com).

For Bassaricyon, we included all newly sequenced and previously available sequences for cytochrome b and CHRNA1 (for cytochrome b this included five individuals of Bassaricyon medius, two Bassaricyon alleni, one Bassaricyon gabbii and three Bassaricyon neblina sp. n.; for CHRNA1 this included five individuals of Bassaricyon medius, two Bassaricyon alleni, and three Bassaricyon neblina sp. n.) (Table 1).

Maximum Parsimony, Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian analyses were performed for each gene and a concatenation of the two genes to check for any incongruence in structure and support of the Bassaricyon clade. All Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic inferences were carried out using the Cipres Portal (

Pairwise distances for cytochrome b were generated using the Kimura 2-parameter model using MEGA4 (

The branch and bound search method implemented in the software package TNT (

Maximum Likelihood analysis was conducted using the software package GARLI 0.96b (

jModeltest version 0.1.1 (

Molecular divergence estimates were generated in BEAST (

To infer geographical range evolution of procyonids we used the Maximum Likelihood model of dispersal-extinction-cladogenesis (DEC) implemented in Lagrange v. 20130526 (

Vouchered localities of occurrence for Bassaricyon used in our analyses were extracted from museum specimen labels, often as clarified by associated field notes and journals, and from definitive published accounts. Gazetteers published by

We used Maximum Entropy Modeling (Maxent) (

With the largest molecular sampling effort to date, we show that Bassaricyon is well resolved as a monophyletic genus (cf.

The family Procyonidae is well resolved as monophyletic (100% bootstrap and probability values) with a divergence date of 21.4 mya (CI 18.1 – 25.0 mya), in agreement with the divergence estimate of 22.6 mya (CI 19.4 – 25.5 mya) by

Phylogeny of the genus Bassaricyon. Phylogeny generated from the concatenated CHRNA1 and cytochrome b sequences. All analyses consistently recovered the same relationships with high support. Divergence dating was generated in BEAST; bars show the 95% confidence interval at each node. Branches without support are collapsed and outgroup clades have been collapsed, leaving monophyletic groupings with 100% support. Data for CHRNA1 are missing for Bassaricyon gabbii, for which DNA was extracted from a museum skull. All nodes in Bassaricyon have 1.00 Bayesian posterior probability, except the split between Bassaricyon gabbii and Bassaricyon alleni/Bassaricyon medius (0.97 Bayesian posterior probability). Non-focal and outgroup taxa are shaded in gray, Bassaricyon species and subspecies are color coded, samples of Bassaricyon medius medius and Bassaricyon neblina neblina that were collected within 5 km of each other in Ecuador are shaded.

The concordance of our recovered topology and estimates of genetic divergence with previous phylogenetic studies of the Procyonidae suggests that data from cytochrome b and CHRNA1 across sampled taxa have provided a well-supported framework in which the species relationships and divergence dates within Bassaricyon can be reliably assessed. Previous molecular phylogenetic studies have included either only one species (e.g.,

Percentage sequence divergence in cytochrome b sequences (Kimura 2-Parameter) among specimens of Bassaricyon (numbers 1-11) and other Procyonidae (numbers 12-18) in our analyses (see Table 1, Figure 1). Numbers across the top row match numbered samples in the vertical column.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bassaricyon medius orinomus (Panama) | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Bassaricyon medius orinomus (Panama) | 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Bassaricyon medius orinomus (Panama) | 0.3 | 0.4 | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Bassaricyon medius medius (Ecuador) | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.6 | ||||||||||||||

| 5. Bassaricyon medius medius (Ecuador) | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.1 | |||||||||||||

| 6. Bassaricyon alleni (Guyana) | 6.9 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 7.4 | ||||||||||||

| 7. Bassaricyon alleni (Peru) | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 1.3 | |||||||||||

| 8. Bassaricyon gabbii (Costa Rica) | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 6.6 | ||||||||||

| 9. Bassaricyon neblina neblina (Ecuador) | 10.1 | 10.1 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 9.9 | |||||||||

| 10. Bassaricyon neblina neblina (Ecuador) | 10.1 | 10.1 | 9.8 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 9.9 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| 11. Bassaricyon neblina osborni (Colombia) | 10.0 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 11.2 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 1.6 | 1.6 | |||||||

| 12. Potos flavus | 28.7 | 28.9 | 28.7 | 29.5 | 29.5 | 29.8 | 29.0 | 28.1 | 29.8 | 29.9 | 28.9 | ||||||

| 13. Procyon lotor | 34.8 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 35.2 | 34.9 | 35.6 | 34.9 | 33.0 | 33.8 | 33.7 | 32.7 | 27.3 | |||||

| 14. Procyon cancrivorus | 31.9 | 31.2 | 31.2 | 32.2 | 32.0 | 32.1 | 29.9 | 31.9 | 32.0 | 31.8 | 30.4 | 29.4 | 13.1 | ||||

| 15. Bassariscus astutus | 30.7 | 30.5 | 30.0 | 29.8 | 30.0 | 30.8 | 30.0 | 29.4 | 29.3 | 29.1 | 29.5 | 29.6 | 20.7 | 17.8 | |||

| 16. Bassariscus sumichrasti | 28.1 | 27.4 | 27.7 | 27.7 | 27.9 | 27.7 | 25.7 | 28.3 | 26.2 | 26.1 | 25.6 | 26.8 | 17.1 | 18.3 | 15.8 | ||

| 17. Nasua nasua | 26.8 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 28.1 | 28.4 | 25.4 | 24.1 | 25.7 | 25.0 | 24.8 | 24.1 | 35.6 | 35.8 | 30.3 | 30.5 | 29.1 | |

| 18. Nasua narica | 30.3 | 29.7 | 30.0 | 30.2 | 30.0 | 29.0 | 29.2 | 28.8 | 25.1 | 25.1 | 24.2 | 31.3 | 29.7 | 26.4 | 27.3 | 26.3 | 20.4 |

We obtained the highest bootstrap and posterior probability support values (100% and 1.0 respectively) for relationships within Bassaricyon with every method of phylogenetic inference that was used in this study. The single exception was that the topology that recovered the node uniting Bassaricyon alleni and Bassaricyon medius to the exclusion of Bassaricyon gabbii was assigned a slightly lower Bayesian posterior probability value of 0.97, but all other methods lent full support to this topology (Bassaricyon gabbii, (Bassaricyon medius, Bassaricyon alleni)). These results were also well-supported by our comparisons of morphological characters and together lend strong support for this scenario as being an accurate representation of the evolutionary history of diversification within Bassaricyon.

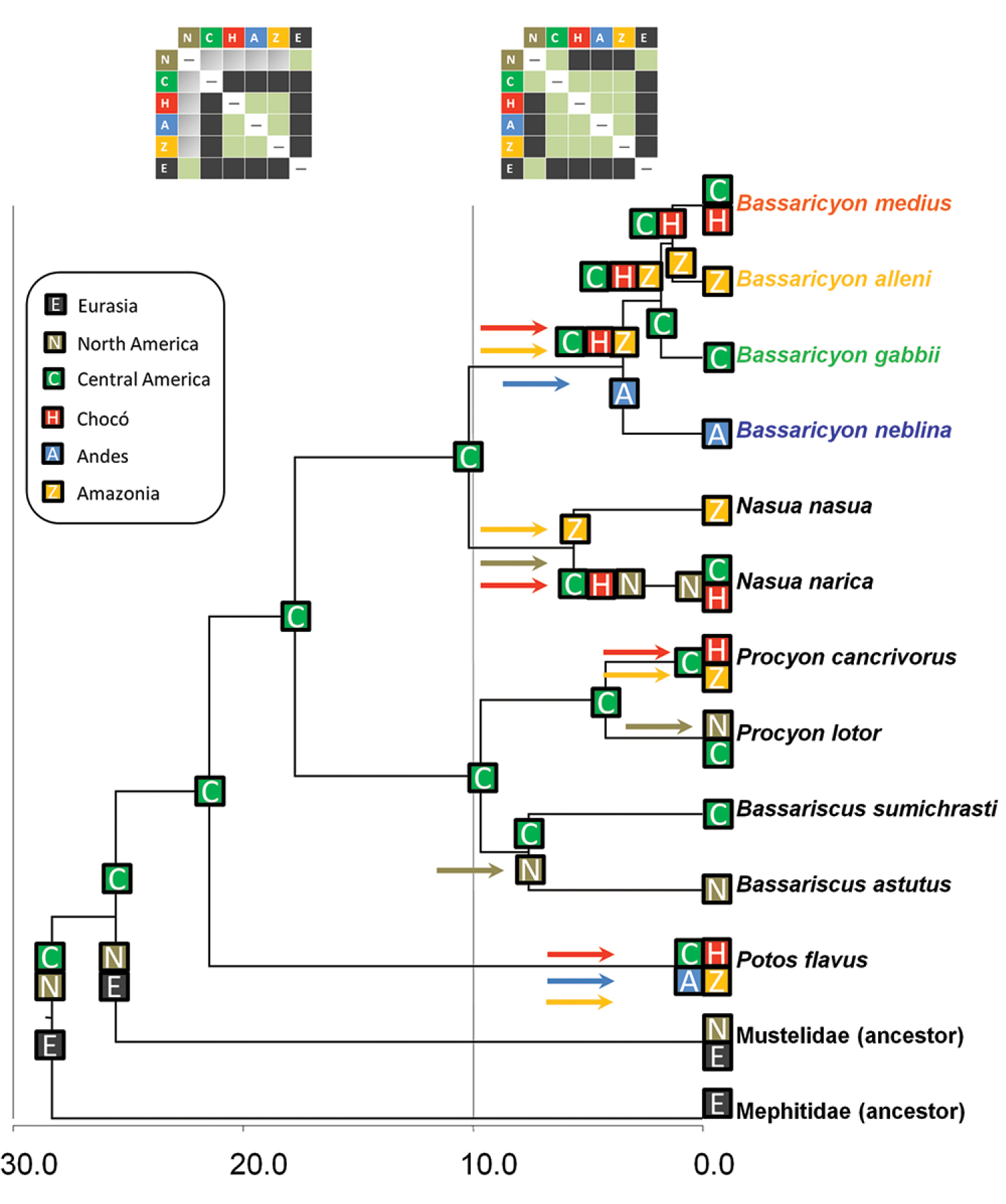

The historical biogeographic reconstruction for the Procyonidae using the DEC model sets Central America as the likely center of origin of crown-group procyonids (Figure 2) (though we note that the family has many extinct, Eocene to Miocene representatives in North America and Europe). Major splits within the family appear to have occurred in Central America previous to the formation of the Panamanian Isthmus, and all the dispersal events resulting in the extant species have occurred within the last 10 million years. All those dispersal events involving southward movements seem to have occurred up to circa 6 mya, coinciding with the initial uplift of the Panamanian Isthmus, and, presumably once it was consolidated, with the Great American Biotic Interchange (GABI) (Figures 1–2). The clade containing all olingo species is likely to have originated directly as a result of the formation of the Panamanian Isthmus, and provides evidence of a complex pattern of dispersal events out of Central America (Figure 2).

Historical biogeography of procyonids. Reconstructed under the DEC model implemented in Lagrange. See legend for geographical areas used in the analysis. Colored squares at the tip of the branches reflect the distribution of taxa, and previously inferred distributions of the ancestors of mustelids and mephitids. Colored squares at the nodes represent the geographic ranges with the highest probabilites in the DEC model inherited by each descendant branch. Colored arrows reflect dispersal events between ancestral and derived areas, with colors matching with recipient areas. Upper boxes: different dispersal constraints at time intervals 0–10 mya and 10–30 mya, the former to simulate the effect of the land bridge formation between Central and South America, the latter restricted dispersal due to the absence of the land bridge; the cells in green indicate no restriction to dispersal, cells in gray indicate a reduction by half in dispersal capability, and cells in black do not allow dispersal. Timescale in millions of years before present (mya).

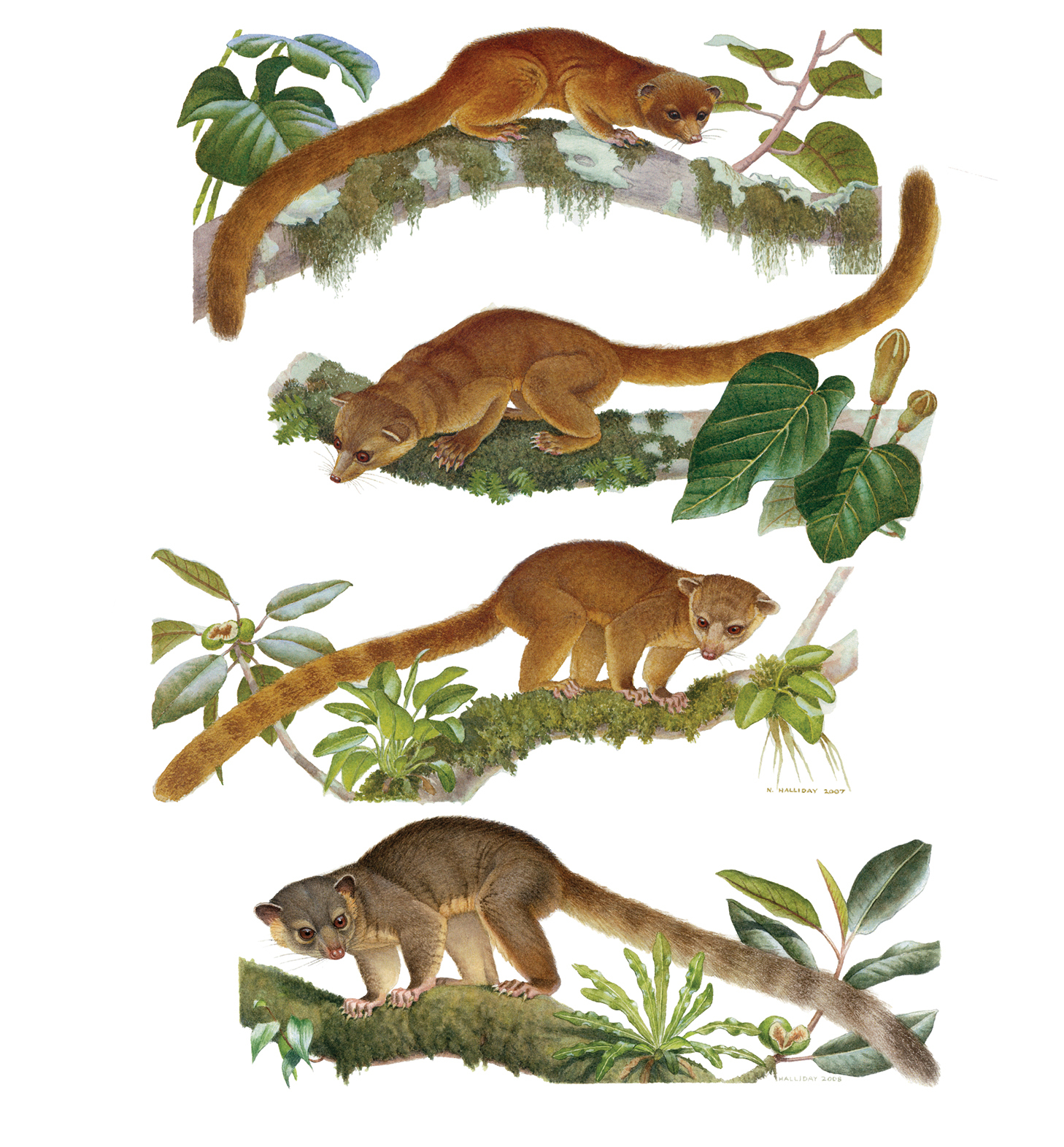

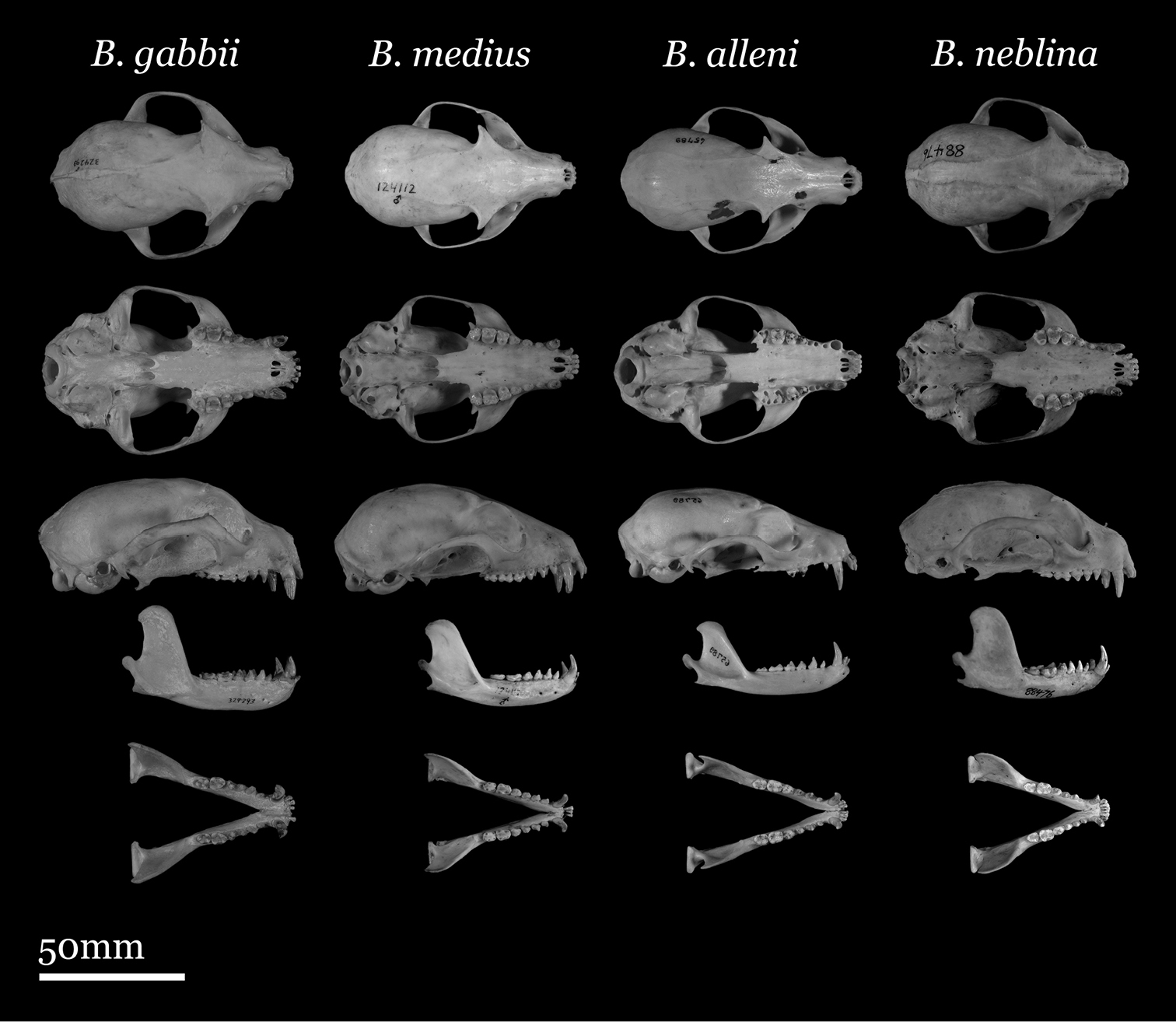

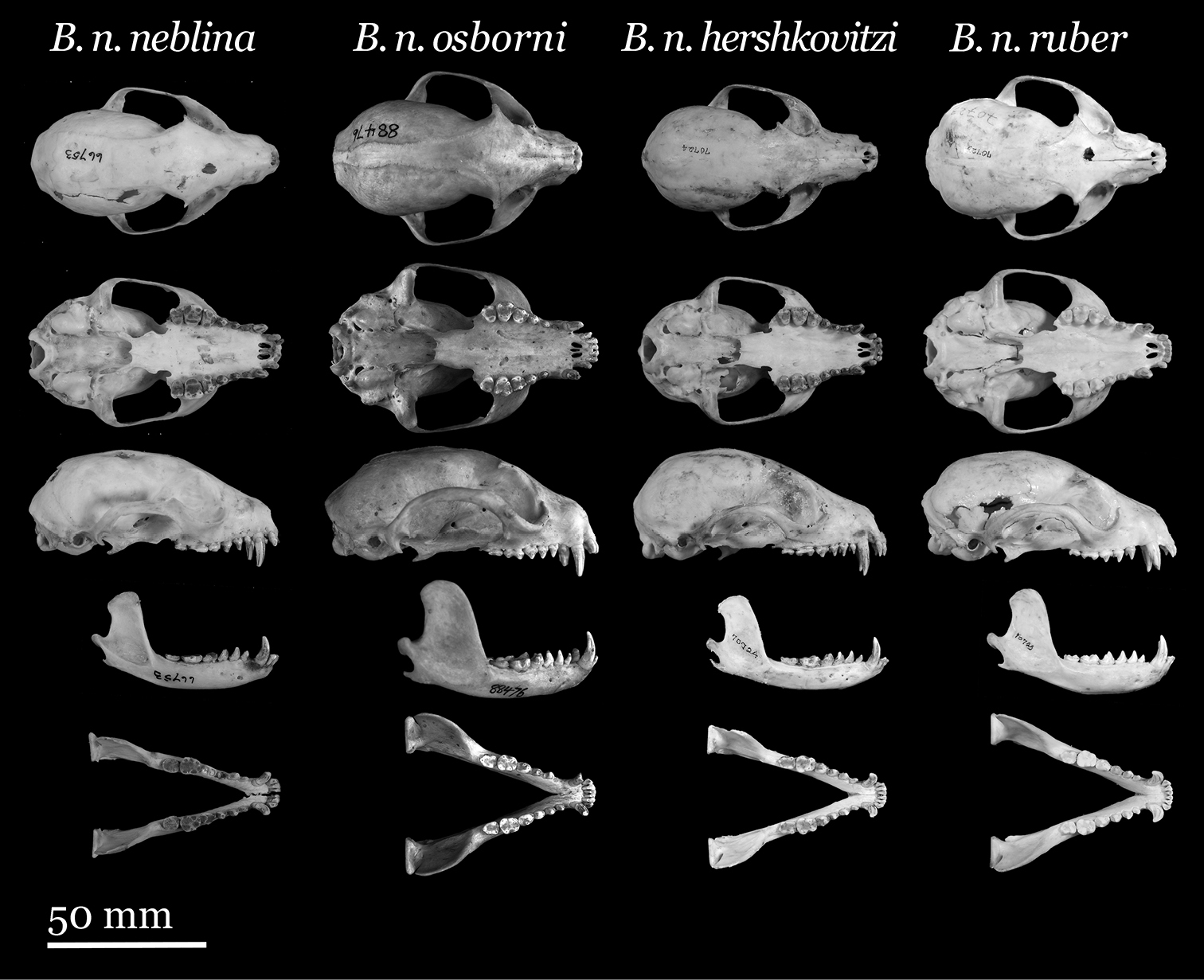

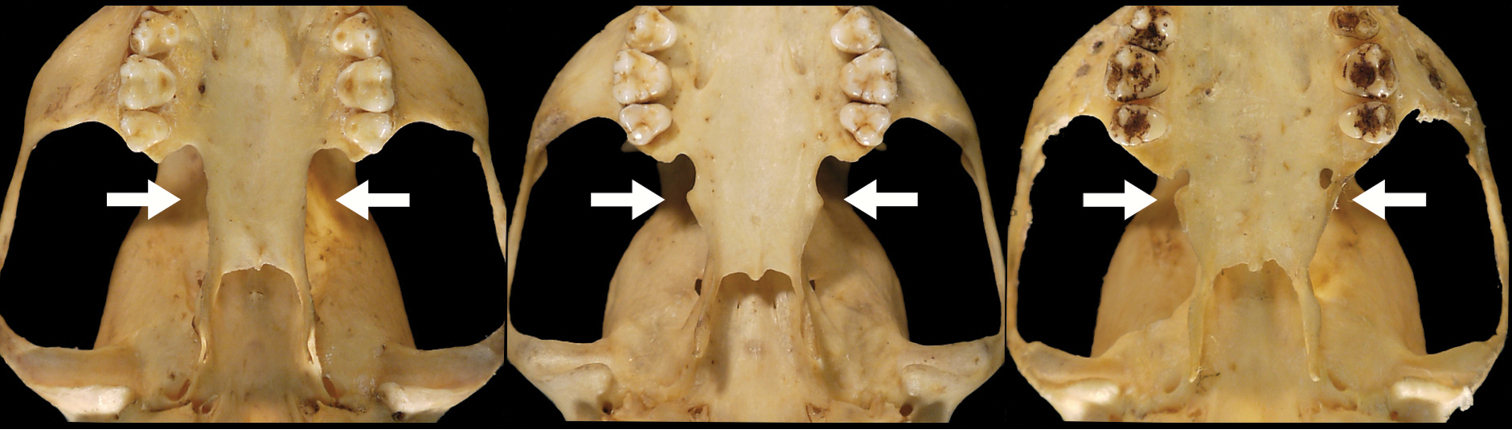

Our study of Bassaricyon taxonomy originally began with close examination of craniodental traits of museum specimens, which quickly revealed to the first author the existence of Bassaricyon neblina sp. n., which is highly distinctive morphologically. Close examinations of skins and skulls revealed clear differences in qualitative traits, and in external and craniodental measurements and proportions, between the four principal Bassaricyon lineages identified in this paper (which we recognize taxonomically as Bassaricyon neblina sp. n., Bassaricyon gabbii, Bassaricyon alleni, and Bassaricyon medius; Figures 3–5). Externally, these especially include differences in body size, pelage coloration, pelage length, relative length of the tail, and relative size of the ears (Figure 3, Table 5). Craniodentally, these especially include differences in skull size, relative size of the premolars and molars, configuration of molar cusps, relative size of the auditory bullae and external auditory meati, and the shape of the postdental palatal shelf (Figures 4–5, Tables 3–4). These and other differences are discussed in greater detail in the species accounts provided later in the paper.

Illustrations of the species of Bassaricyon. From top to bottom, Bassaricyon neblina sp. n. (Bassaricyon neblina ruber subsp. n. of the western slopes of the Western Andes of Colombia), Bassaricyon medius (Bassaricyon medius orinomus of eastern Panama), Bassaricyon alleni (Peru), and Bassaricyon gabbii (Costa Rica, showing relative tail length longer than average). Artwork by Nancy Halliday.

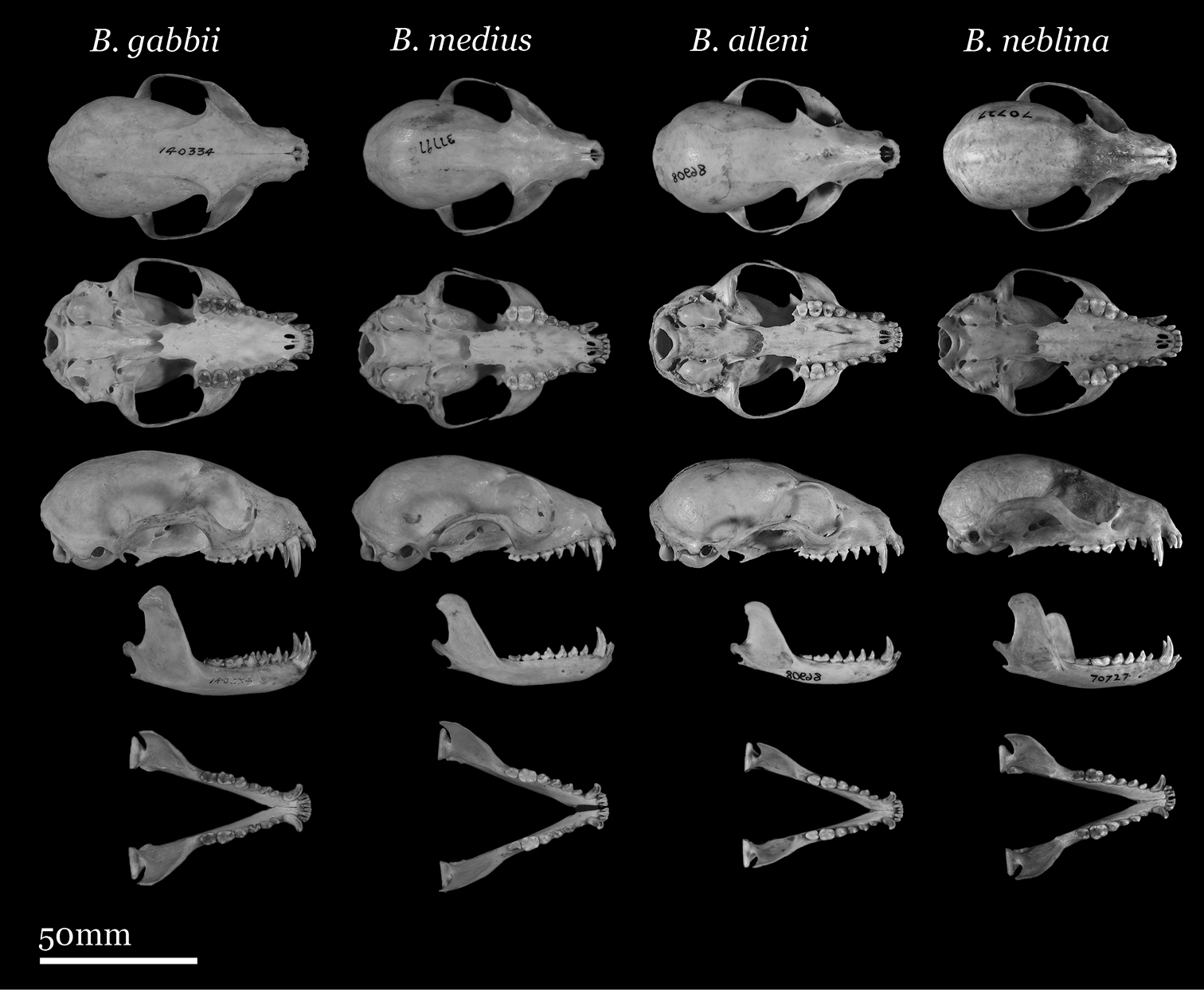

Skulls of adult male Bassaricyon. From left to right: Bassaricyon gabbii (USNM 324293, Cerro Punta, 1700 m, Chiriqui Mountains, Panama); Bassaricyon medius medius (MVZ 124112, Dagua, 1800 m, Colombia); Bassaricyon alleni (FMNH 65789, Chanchamayo, 1200 m, Junin, Peru); Bassaricyon neblina osborni (FMNH 88476, Munchique, 2000 m, Cauca, Colombia). Scale bar = 50 mm.

Skulls of adult female Bassaricyon. From left to right: Bassaricyon gabbii (AMNH 140334, Lajas Villa, Costa Rica); Bassaricyon medius orinomus (AMNH 37797, Puerta Valdivia, Antioquia District, Colombia); Bassaricyon alleni (FMNH 86908, Santa Rita, Rio Nanay, Maynas, Loreto Region, Peru); Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi (FMNH 70727, San Antonio, Agustin, Huila District, Colombia). Scale bar = 50 mm.

Cranial measurements for olingo species (compiled separately by sex). For each measurement, means are provided, ± standard deviation, with ranges in parentheses.

|

Bassaricyon gabbii n= 11 ♂♂, 11 ♀♀ |

Bassaricyon medius n= 18 ♂♂, 27 ♀♀ |

Bassaricyon alleni n= 12 ♂♂, 17 ♀♀ |

Bassaricyon neblina n= 10 ♂♂, 9 ♀♀ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBL | ♂♂ | 80.8 ± 1.50 (78.1 - 83.0) |

79.4 ± 2.67 (74.5 - 85.1) |

79.4 ± 1.81 (76.5 - 82.8) |

74.5 ± 3.26 (70.1 - 79.5) |

| ♀♀ | 78.2 ± 1.75 (75.0 - 80.2) |

77.3 ± 2.70 (70.8 - 82.3) |

77.0 ± 2.24 (73.1 - 80.5) |

75.1 ± 1.49 (72.9 - 77.9) |

|

| ZYG | ♂♂ | 55.2 ± 2.76 (49.5 - 58.7) |

52.0 ± 2.66 (48.3 - 56.7) |

51.6 ± 1.02 (49.0 - 52.8) |

50.1 ± 3.02 (46.2 - 54.4) |

| ♀♀ | 51.3 ± 1.90 (48.1 - 54.4) |

50.0 ± 2.50 (44.4 - 54.0) |

50.2 ± 0.99 (48.6 - 52.2) |

49.0 ± 2.69 (44.6 - 53.0) |

|

| BBC | ♂♂ | 36.1 ± 0.86 (34.3 - 37.6) |

35.1 ± 1.16 (32.9 - 37.5) |

35.4 ± 0.80 (34.2 - 36.8) |

34.6 ± 1.62 (32.4 - 37.5) |

| ♀♀ | 35.7 ± 1.34 (33.1 - 37.5) |

34.6 ± 1.20 (32.0 - 37.2) |

34.9 ± 0.91 (33.3 - 36.8) |

34.2 ± 1.62 (31.0 - 36.6) |

|

| HBC | ♂♂ | 28.7 ± 0.88 (26.4 - 29.7) |

27.6 ± 0.84 (26.5 - 29.3) |

27.4 ± 0.73 (26.2 - 28.5) |

27.4 ± 0.61 (26.5 - 28.3) |

| ♀♀ | 27.9 ± 0.74 (26.9 - 28.8) |

26.9 ± 0.90 (25.4 - 28.5) |

26.9 ± 0.63 (26.0 - 28.1) |

26.5 ± 0.93 (24.9 - 27.8) |

|

| MTR | ♂♂ | 28.5 ± 0.50 (27.8 - 29.3) |

28.6 ± 0.87 (27.0 - 30.4) |

28.4 ± 0.83 (26.5 - 29.5) |

26.5 ± 1.38 (24.5 - 28.7) |

| ♀♀ | 27.3 ± 1.02 (26.0 - 29.0) |

27.7 ± 0.90 (25.6 - 29.1) |

27.3 ± 0.69 (26.1 - 28.5) |

26.9 ± 0.88 (25.8 - 28.3) |

|

| CC | ♂♂ | 18.7 ± 1.12 (17.2 - 20.4) |

16.4 ± 0.92 (15.0 - 17.9) |

16.8 ± 0.51 (15.8 - 17.6) |

15.9 ± 0.94 (14.7 - 17.1) |

| ♀♀ | 16.9 ± 0.76 (15.6 - 17.9) |

15.7 ± 0.80 (14.5 - 17.2) |

15.9 ± 0.55 (14.8 - 16.8) |

15.7 ± 0.47 (14.9 - 16.4) |

|

| WPP | ♂♂ | 11.3 ± 1.27 (9.0 - 12.9) |

10.3 ± 0.95 (8.4 - 12.1) |

10.4 ± 0.82 (8.7 - 11.8) |

11.7 ± 1.05 (10.6 - 14.0) |

| ♀♀ | 10.7 ± 0.99 (9.3 - 12.7) |

10.3 ± 0.90 (9.0 - 13.0) |

9.9 ± 0.89 (8.2 - 11.7) |

11.6 ± 0.87 (10.5 - 12.7) |

|

| LPP | ♂♂ | 12.3 ± 0.99 (10.7 - 14.0) |

10.2 ± 0.88 (7.9 - 11.7) |

10.8 ± 1.21 (9.3 - 12.9) |

11.2 ± 1.24 (9.2 - 12.7) |

| ♀♀ | 10.8 ± 0.77 (9.7 - 12.0) |

10.1 ± 0.90 (8.1 - 11.8) |

10.4 ± 0.67 (8.7 - 11.6) |

11.1 ± 0.82 (9.7 - 12.3) |

|

| LAB | ♂♂ | 13.8 ± 0.63 (12.9 - 14.7) |

14.0 ± 0.81 (12.8 - 15.6) |

15.1 ± 0.76 (14.1 - 16.8) |

11.8 ± 0.76 (10.9 - 13.3) |

| ♀♀ | 13.8 ± 0.67 (12.9 - 14.8) |

14.0 ± 0.80 (12.6 - 15.2) |

14.4 ± 0.81 (13.0 - 15.6) |

12.2 ± 0.51 (11.0 - 12.7) |

|

| EAM | ♂♂ | 3.6 ± 0.47 (2.6 - 4.2) |

3.9 ± 0.33 (3.4 - 4.5) |

3.8 ± 0.40 (3.2 - 4.5) |

2.9 ± 0.22 (2.5 - 3.1) |

| ♀♀ | 3.6 ± 0.39 (3.0 - 4.2) |

3.9 ± 0.30 (3.5 - 4.7) |

3.8 ± 0.36 (3.2 - 4.4) |

3.2 ± 0.33 (2.6 - 3.5) |

|

Selected dental measurements of olingo species. For each measurement, means are provided, ± standard deviation, with ranges in parentheses.

|

Bassaricyon gabbii n= 22 |

Bassaricyon medius n= 45 |

Bassaricyon alleni n= 34 |

Bassaricyon neblina n= 19 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p1 width | 1.7 ± 0.17 (1.4 - 2.1) |

1.7 ± 0.13 (1.4 - 2.0) |

1.7 ± 0.12 (1.5 - 1.9) |

1.6 ± 0.13 (1.4 - 1.8) |

| p2 width | 2.4 ± 0.24 (2.0 - 2.8) |

2.2 ± 0.18 (1.8 - 2.6) |

2.2 ± 0.15 (1.9 - 2.5) |

2.1 ± 0.17 (1.9 - 2.5) |

| p3 width | 2.7 ± 0.21 (2.3 - 3.0) |

2.5 ± 0.18 (2.2 - 2.9) |

2.6 ± 0.16 (2.2 - 2.9) |

2.4 ± 0.22 (2.1 - 2.9) |

| p4 width | 3.4 ± 0.27 (3.0 - 3.9) |

3.2 ± 0.18 (2.8 - 3.6) |

3.4 ± 0.21 (2.8 - 3.7) |

3.3 ± 0.15 (3.0 - 3.7) |

| P2 width | 2.4 ± 0.24 (2.1 - 2.9) |

2.3 ± 0.19 (1.9 - 2.8) |

2.2 ± 0.17 (1.9 - 2.7) |

2.1 ± 0.19 (1.8 - 2.5) |

| P3 width | 2.9 ± 0.22 (2.5 - 3.3) |

3.0 ± 0.29 (2.5 - 3.6) |

3.0 ± 0.22 (2.6 - 3.5) |

2.9 ± 0.21 (2.6 - 3.4) |

| P4 length | 4.4 ± 0.24 (3.9 - 4.8) |

4.2 ± 0.27 (3.6 - 4.9) |

4.2 ± 0.20 (3.8 - 4.6) |

4.5 ± 0.24 (4.1 - 4.9) |

| P4 width | 5.1 ± 0.35 (4.5 - 5.6) |

4.7 ± 0.26 (4.2 - 5.4) |

4.8 ± 0.23 (4.4 - 5.6) |

5.0 ± 0.40 (4.5 - 5.9) |

| M1 length | 5. 0 ± 0.27 (4.4 - 5.4) |

5.0 ± 0.29 (4.3 - 5.6) |

5.1 ± 0.21 (4.6 - 5.5) |

5.3 ± 0.35 (4.8 - 6.1) |

| M1 width | 5.5 ± 0.30 (4.7 - 5.9) |

5.3 ± 0.32 (4.7 - 5.9) |

5.5 ± 0.28 (4.9 - 6.0) |

5.8 ± 0.31 (5.4 - 6.4) |

| M2 length | 3.7 ± 0.32 (2.8 - 4.1) |

4.0 ± 0.25 (3.2 - 4.4) |

3.8 ± 0.27 (3.3 - 4.4) |

3.8 ± 0.35 (3.3 - 4.4) |

| M2 width | 4.6 ± 0.38 (4.0 - 5.3) |

4.7 ± 0.27 (4.1 - 5.2) |

4.7 ± 0.28 (4.0 - 5.2) |

4.8 ± 0.24 (4.4 - 5.4) |

| m1 length | 5.6 ± 0.31 (5.0 - 6.3) |

5.7 ± 0.26 (4.9 - 6.2) |

5.6 ± 0.22 (5.2 - 6.0) |

5.8 ± 0.29 (5.4 - 6.3) |

| m1 width | 4.3 ± 0.29 (3.8 - 4.9) |

4.3 ± 0.21 (3.9 - 4.7) |

4.3 ± 0.23 (3.7 - 4.8) |

4.8 ± 0.22 (4.5 - 5.3) |

| m2 length | 4.8 ± 0.25 (4.4 - 5.3) |

5.1 ± 0.36 (4.2 - 5.7) |

4.8 ± 0.25 (4.4 - 5.4) |

5.0 ± 0.35 (4.4 - 5.6) |

| m2 width | 3.8 ± 0.24 (3.3 - 4.2) |

3.7 ± 0.24 (3.2 - 4.2) |

3.7 ± 0.19 (3.3 - 4.0) |

3.8 ± 0.17 (3.5 - 4.1) |

External measurements of olingo species. For each measurement, means are provided, ± standard deviation, with ranges in parentheses.

|

Bassaricyon gabbii n= 13 |

Bassaricyon medius n= 36 |

Bassaricyon alleni n= 27 |

Bassaricyon neblina n= 19 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL | 873 ± 54.8 (785 - 970) |

819 ± 60.5 (680 - 905) |

842 ± 50.6 (705 - 985) |

745 ± 33.7 (660 - 820) |

| Tail | 445 ± 40.3 (400 - 521) |

441 ± 44.6 (350 - 520) |

450 ± 28.8 (401 - 530) |

390 ± 21 (335 - 424) |

| HF | 84 ± 8.7 (65 - 100) |

81 ± 7.3 (58 - 92) |

81 ± 5.8 (70 - 92) |

76 ± 6.9 (60 - 86) |

| Ear | 36 ± 4.7 (25 - 44) |

37 ± 5.4 (25 - 44) |

37 ± 3.4 (30 - 43) |

34 ± 4.3 (25 - 39) |

| Mass (g) | 1382 ± 165 (1136 - 1580) |

1076 ± 71.6 (915 - 1200) |

1336 ± 152 (1100 - 1500) |

872 ± 169 (750 - 1065) |

| HB | 428 ± 27.9 (373 - 470) |

379 ± 23.2 (310 - 415) |

391 ± 29.3 (304 - 455) |

355 ± 21.1 (325 - 400) |

| Tail/HB | 1.04 ± 0.1 (0.9 - 1.2) |

1.16 ± 0.1 (1.0 - 1.4) |

1.15 ± 0.08 (1.0 - 1.3) |

1.10 ± 0.08 (1.0 - 1.2) |

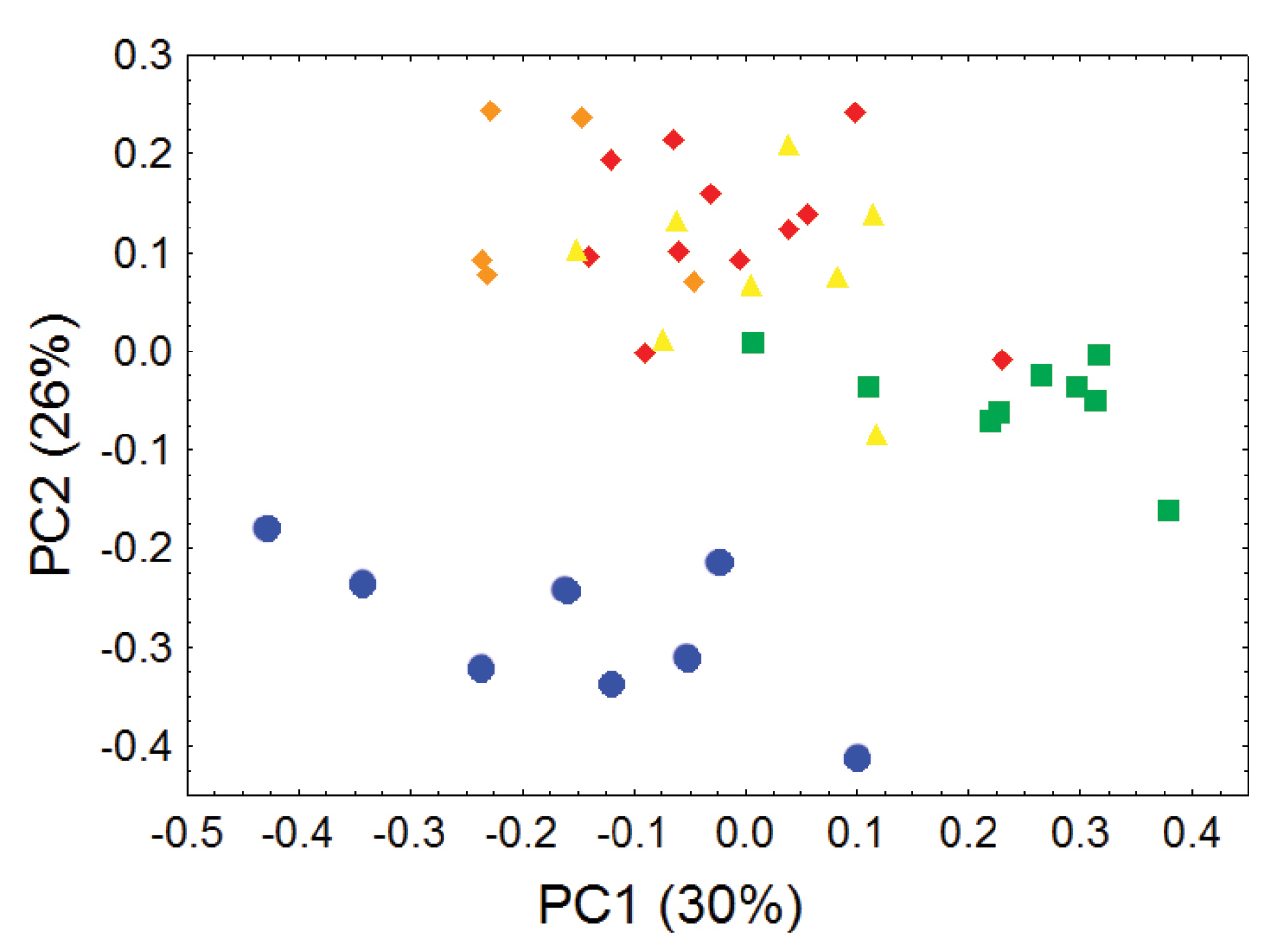

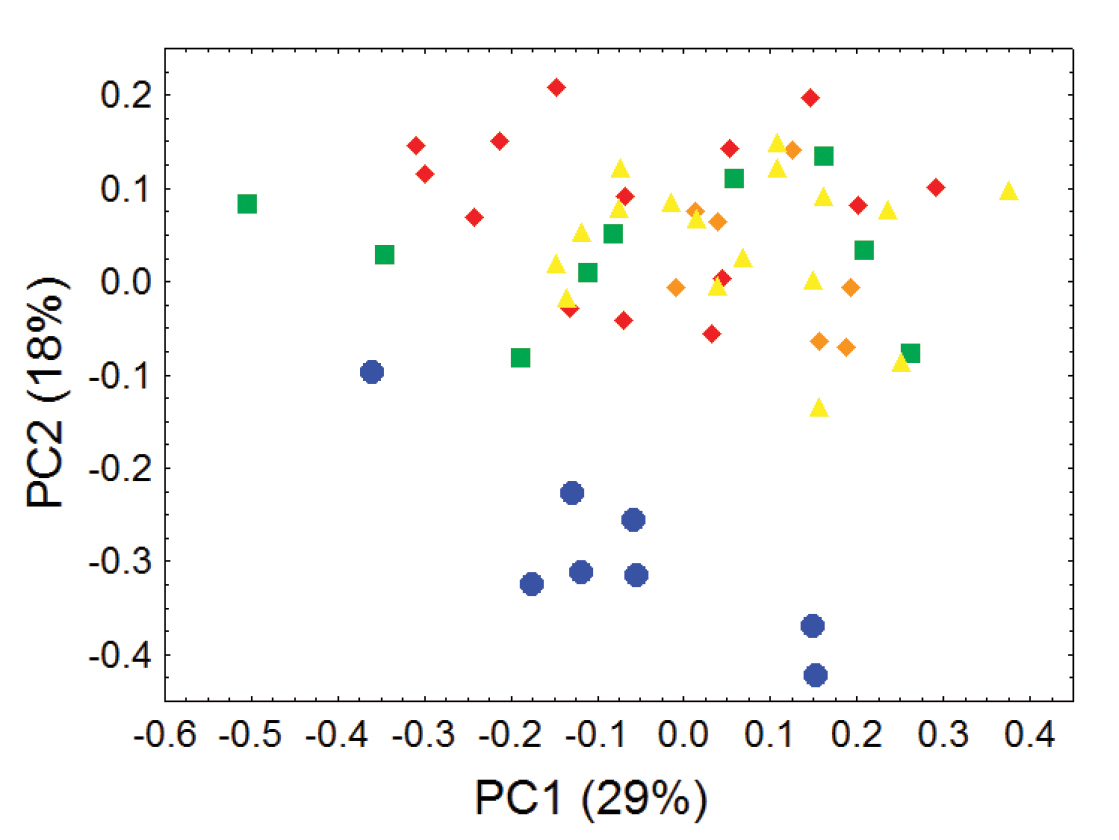

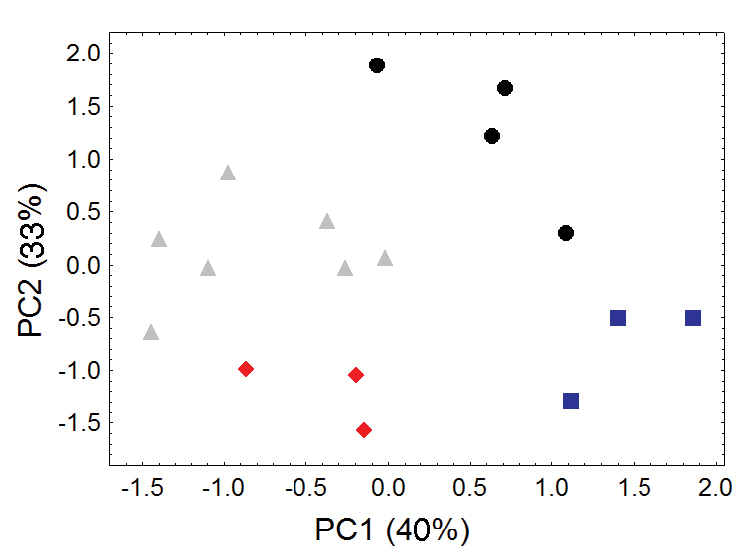

Principal component analyses of cranial and dental measurements support our molecular results in clearly identifying a fundamental morphometric separation between the Olinguito (Bassaricyon neblina sp. n.) and all other Bassaricyon taxa, in separate comparisons involving both males and females (Figures 6–7, Appendix 1). When first and second principal components are juxtaposed in a bivariate plot, Olinguito specimens demonstrate clear morphometric separation from all other Bassaricyon, despite overlap between these clusters in body size (as indicated by overlap in the first principal component, on which all or most variables in the analysis show positive [males] or negative [females] loadings). Despite smaller average body size compared to other Bassaricyon, the morphometric distinctness of Olinguito specimens is reflected not especially in small size but rather primarily by separation along the second principal component, indicating trenchant differences in overall shape and proportion, especially reflecting consistent differences in the molars, auditory bullae, external auditory meati, and palate, in which the Olinguito differs strongly and consistently from other Bassaricyon (Figures 6–7, Tables 3–4, Appendix 1).

Morphometric distinction between Olinguitos and other Bassaricyon, males. Morphometric dispersion (first two components of a principal component analysis) of 41 adult male Bassaricyon skulls based on 21 craniodental measurements (see Appendix 1, Table A1). The most notable morphometric distinction is between the Olinguito (blue circles) and all other Bassaricyon taxa. The plot also demonstrates substantial morphometric variability across geographic populations of the Olinguito, which we characterize with the description of four subspecies across different Andean regions. Symbols: blue circles (Bassaricyon neblina), green squares (Bassaricyon gabbii), yellow triangles (Bassaricyon alleni), orange diamonds (Bassaricyon medius medius), red diamonds (Bassaricyon medius orinomus).

Morphometric distinction between Olinguitos and other Bassaricyon, females. Morphometric dispersion (first two components of a principal component analysis) of 55 adult female Bassaricyon skulls based on 24 craniodental measurements (see Appendix 1, Table A2). The most notable morphometric distinction is between the Olinguito (blue circles) and all other Bassaricyon taxa. The plot also demonstrates substantial morphometric variability across geographic populations of the Olinguito, which we characterize with the description of four subspecies across different Andean regions. Symbols: blue circles (Bassaricyon neblina), green squares (Bassaricyon gabbii), yellow triangles (Bassaricyon alleni), orange diamonds (Bassaricyon medius medius), red diamonds (Bassaricyon medius orinomus).

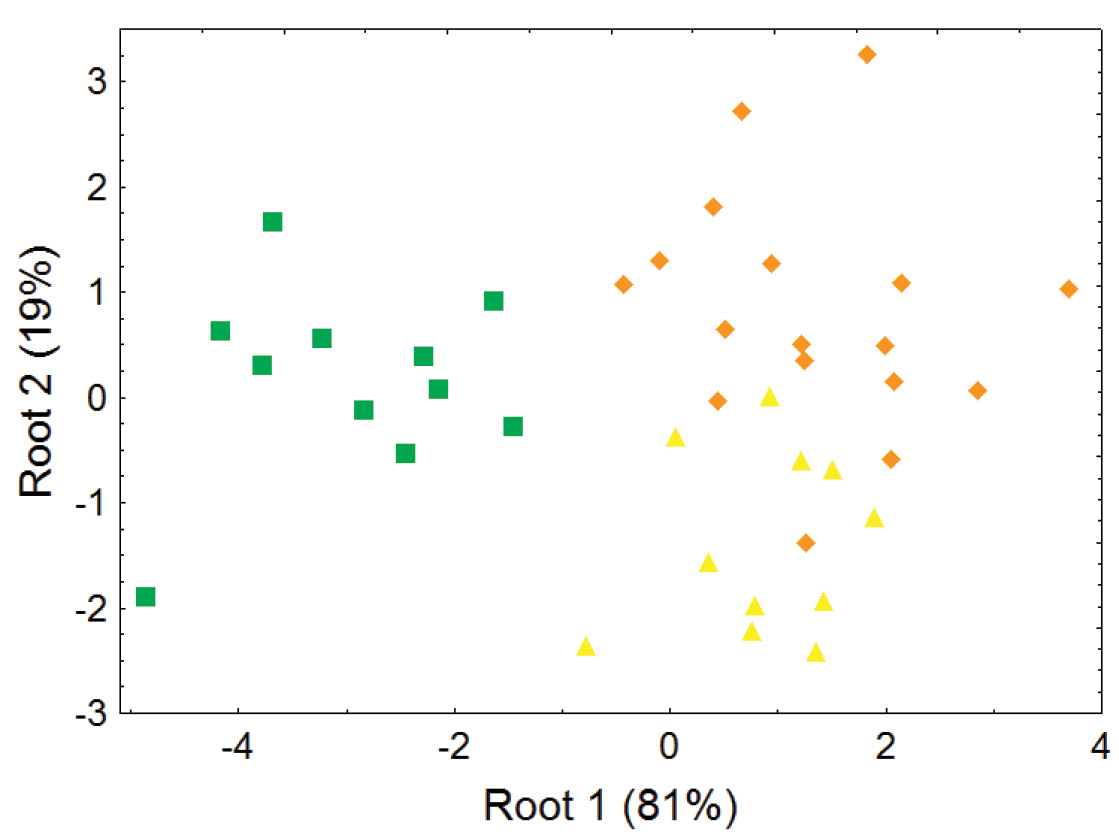

The lower elevation olingo taxa Bassaricyon gabbii, Bassaricyon medius, and Bassaricyon alleni are not separable in most principal component analyses of craniodental measurements (e.g., Figures 6–7), but discriminant function analyses of craniodental measurements (e.g., Figure 8, showing separation of male skulls) separates them into discrete clusterings with few misclassifications, and identifies some of the more important craniodental traits that help to distinguish between them (Appendix 1). These (and other, qualitative) craniodental distinctions are complemented by differences in pelage features and genetic divergences that we discuss below.

Morphometric distinction between species of Bassaricyon, excluding the Olinguito, adult males. Morphometric dispersion (first two variates of a discriminant function analysis) of 39 adult male Bassaricyon skulls based on 8 craniodental measurements (see Appendix 1, Table A3). Symbols: green squares (Bassaricyon gabbii), yellow triangles (Bassaricyon alleni), orange diamonds (Bassaricyon medius).

Because of marked and consistent differences in body size between the two regional populations of Bassaricyon medius (one distributed in western South America, the other primarily distributed in Panama), we choose to recognize these two as separate subspecies (Bassaricyon medius medius and Bassaricyon medius orinomus, respectively, Tables 6–7). The Olinguito likewise shows a clear pattern of geographic variation, with different regional populations in the Northern Andes showing consistent differences in craniodental size and morphology (Figures 9–10, Table 8, Appendix 1), as well as pelage coloration and length. We recognize four distinctive subspecies of the Olinguito throughout its recorded distribution, as discussed in the description of Bassaricyon neblina sp. n., below. Two of these subspecies are included in our genetic comparisons; genetic comparisons involving the remaining two subspecies remain a goal for the future.

Cranial measurements for the two subspecies of Bassaricyon medius. For each measurement, means are provided, ± standard deviation, with ranges in parentheses.

| Bassaricyon medius medius | Bassaricyon medius orinomus | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| W Colombia, W Ecuador | C Panama to N Colombia | ||

| n = 5 ♂♂, 7 ♀♀ | n = 12 ♂♂, 17 ♀♀ | ||

| CBL | ♂♂ | 77.2 ± 1.81 (74.5 - 78.8) | 80.3 ± 2.50 (76.2 - 85.1) |

| ♀♀ | 75.4 ± 1.65 (72.4 - 76.7) | 78.8 ± 1.72 (75.5 - 82.3) | |

| ZYG | ♂♂ | 50.2 ± 1.14 (48.9 - 51.2) | 53.0 ± 2.57 (48.9 - 56.7) |

| ♀♀ | 48.5 ± 1.69 (46.5 – 51.0) | 51.2 ± 1.98 (47.4 – 54.0) | |

| BBC | ♂♂ | 34.0 ± 0.80 (32.9 - 34.8) | 35.6 ± 0.98 (34.0 - 37.5) |

| ♀♀ | 34.4 ± 0.41 (33.7 – 35.0) | 35.0 ± 1.15 (32.8 - 37.2) | |

| HBC | ♂♂ | 28.2 ± 1.06 (27.1 - 29.3) | 27.4 ± 0.62 (26.6 - 28.3) |

| ♀♀ | 26.8 ± 0.89 (26.1 - 28.5) | 27.0 ± 0.89 (25.4 - 28.5) | |

| MTR | ♂♂ | 28.5 ± 0.97 (27.3 - 29.8) | 28.7 ± 0.90 (27.0 - 30.4) |

| ♀♀ | 27.1 ± 0.78 (25.6 - 27.9) | 28.0 ± 0.77 (26.4 - 29.1) | |

| CC | ♂♂ | 15.9 ± 0.69 (15.1 - 17.0) | 16.7 ± 0.94 (15.0 - 17.9) |

| ♀♀ | 15.0 ± 0.46 (14.5 - 15.8) | 16.1 ± 0.71 (14.6 - 17.2) | |

| WPP | ♂♂ | 9.7 ± 0.95 (8.4 - 10.8) | 10.6 ± 0.91 (8.6 - 12.1) |

| ♀♀ | 10.0 ± 0.57 (9.1 - 10.6) | 10.3 ± 1.04 (9.0 - 13.0) | |

| LPP | ♂♂ | 9.4 ± 1.03 (7.9 - 10.6) | 10.5 ± 0.64 (9.8 - 11.7) |

| ♀♀ | 9.8 ± 0.84 (8.9 - 11.3) | 10.2 ± 1.01 (8.1 - 11.8) | |

| LAB | ♂♂ | 13.6 ± 0.72 (12.8 - 14.6) | 14.2 ± 0.84 (13.1 - 15.6) |

| ♀♀ | 13.4 ± 0.45 (12.6 - 13.9) | 14.3 ± 0.73 (12.8 - 15.2) | |

| EAM | ♂♂ | 3.9 ± 0.47 (3.4 - 4.5) | 3.9 ± 0.27 (3.5 - 4.4) |

| ♀♀ | 3.9 ± 0.34 (3.5 - 4.4) | 3.9 ± 0.28 (3.6 - 4.7) | |

External measurements for the two subspecies of Bassaricyon medius. For each measurement, means are provided, ± standard deviation, with ranges in parentheses.

|

Bassaricyon medius medius W Colombia, W Ecuador n= 12 |

Bassaricyon medius orinomus C Panama to N Colombia n= 24 |

|

|---|---|---|

| TL | 754 ± 49.7 (680 - 819) | 844 ± 42.9 (770 - 905) |

| Tail | 392 ± 29.1 (350 - 435) | 460 ± 33.6 (400 - 520) |

| HF | 73 ± 5.4 (58 - 79) | 85 ± 3.5 (77 - 92) |

| Ear | 32 ± 4.8 (25 - 40) | 39 ± 4 (30 - 44) |

| Mass (g) | 1058 ± 146 (915 - 1200) | 1090 ± 19.2 (1050 - 1100) |

| HB | 362 ± 29.5 (310 - 415) | 385 ± 17.2 (355 - 410) |

| Tail/HB | 1.1 ± 0.09 (0.97 - 1.24) | 1.2 ± 0.08 (1.04 - 1.35) |

Morphometric distinction between Olinguito subspecies. Both sexes combined. Morphometric dispersion (first two components of a principal component analysis) of 17 adultskulls based on 13 cranial measurements (see Appendix 1, Table A4). (Dental measurements also discretely partition these subspecies in a separate principal component analysis, not shown.) Black dots = Bassaricyon neblina neblina; gray triangles = Bassaricyon neblina osborni; red diamonds = Bassaricyon neblina ruber; blue squares = Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi.

Skulls of Olinguito subspecies. From left to right: Bassaricyon neblina neblina (AMNH 66753, holotype, old adult female, Las Maquinas, Ecuador); Bassaricyon neblina osborni (FMNH 88476, holotype, adult male, Munchique, 2000 m, Cauca Department, Colombia); Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi (FMNH 70724, paratype, adult male, San Antonio, Agustin, Huila District, Colombia); Bassaricyon neblina ruber (FMNH 70723, paratype, adult male, Guapantal, 2200 m, Urrao, Antioquia Department, Colombia). Scale bar = 50 mm.

Dental and cranial measurements of Olinguito (Bassaricyon neblina) subspecies. For each measurement, means are provided, ± standard deviation, with ranges in parentheses.

|

Bassaricyon neblina ruber n= 3 |

Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi n= 4 |

Bassaricyon neblina osborni n= 8 |

Bassaricyon neblina neblina n= 4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p1 width | 1.4 ± 0.06 (1.4 - 1.5) |

1.5 ± 0.12 (1.4 - 1.6) |

1.6 ± 0.09 (1.6 - 1.8) |

1.7 ± 0.11 (1.5 - 1.8) |

| p2 width | 2.1 ± 0.14 (1.9 - 2.2) |

1.9 ± 0.06 (1.9 – 2.0) |

2.2 ± 0.15 (2.0 - 2.5) |

2.2 ± 0.17 (2.1 - 2.4) |

| p3 width | 2.4 ± 0.08 (2.3 - 2.5) |

2.2 ± 0.06 (2.1 - 2.2) |

2.5 ± 0.16 (2.4 - 2.8) |

2.4 ± 0.32 (2.2 - 2.9) |

| p4 width | 3.3 ± 0.11 (3.2 - 3.4) |

3.1 ± 0.12 (3.0 - 3.3) |

3.4 ± 0.13 (3.2 - 3.7) |

3.4 ± 0.09 (3.3 - 3.5) |

| P2 width | 2.0 (2.0 – 2.0) |

1.9 ± 0.05 (1.8 – 2.0) |

2.2 ± 0.17 (2.1 - 2.5) |

2.3 ± 0.15 (2.2 - 2.5) |

| P3 width | 2.9 ± 0.17 (2.7 - 3.1) |

2.7 ± 0.10 (2.6 - 2.8) |

3.0 ± 0.19 (2.8 - 3.4) |

3.1 ± 0.15 (2.9 - 3.3) |

| P4 length | 4.3 ± 0.21 (4.1 - 4.5) |

4.2 ± 0.13 (4.1 - 4.3) |

4.5 ± 0.17 (4.3 - 4.8) |

4.7 ± 0.17 (4.5 - 4.9) |

| P4 width | 4.6 ± 0.14 (4.5 - 4.8) |

5.0 ± 0.23 (4.8 - 5.3) |

4.9 ± 0.20 (4.6 - 5.1) |

5.7 ± 0.13 (5.6 - 5.9) |

| M1 length | 5.0 ± 0.12 (5.0 - 5.2) |

5.0 ± 0.25 (4.8 - 5.4) |

5.3 ± 0.23 (5.0 - 5.6) |

5.7 ± 0.4 (5.2 - 6.1) |

| M1 width | 5.5 ± 0.14 (5.4 - 5.6) |

5.5 ± 0.10 (5.4 - 5.6) |

5.8 ± 0.20 (5.5 - 6.1) |

6.2 ± 0.13 (6.1 - 6.4) |

| M2 length | 3.6 ± 0.22 (3.5 - 3.9) |

3.5 ± 0.16 (3.3 - 3.7) |

4.1 ± 0.29 (3.6 - 4.4) |

3.9 ± 0.4 (3.3 - 4.2) |

| M2 width | 4.5 ± 0.13 (4.4 - 4.6) |

4.7 ± 0.03 (4.7 - 4.8) |

4.8 ± 0.20 (4.6 - 5.2) |

4.9 ± 0.3 (4.7 - 5.4) |

| m1 length | 5.5 ± 0.05 (5.4 - 5.5) |

5.8 ± 0.21 (5.6 – 6.0) |

5.8 ± 0.18 (5.6 – 6.0) |

6.2 ± 0.03 (6.2 - 6.3) |

| m1 width | 4.7 ± 0.12 (4.6 - 4.8) |

4.8 ± 0.17 (4.7 – 5.0) |

4.8 ± 0.26 (4.5 - 5.3) |

5.0 ± 0.22 (4.7 - 5.2) |

| m2 length | 4.7 ± 0.39 (4.4 - 5.1) |

5.0 ± 0.37 (4.5 - 5.2) |

5.2 ± 0.26 (4.9 - 5.6) |

4.8 ± 0.22 (4.5 - 5.1) |

| m2 width | 3.7 ± 0.09 (3.6 - 3.8) |

3.7 ± 0.19 (3.5 - 3.9) |

3.9 ± 0.10 (3.7 - 4.0) |

3.9 ± 0.16 (3.7 - 4.1) |

| CBL | 73.0 ± 0.58 (72.4 - 73.5) |

71.4 ± 1.13 (70.1 - 72.9) |

76.6 ± 1.64 (75.1 - 79.5) |

75.9 ± 1.4 (74.6 - 77.9) |

| ZYG | 51.1 ± 2.28 (48.9 - 53.4) |

46.7 ± 0.60 (46.2 - 47.5) |

51.7 ± 1.73 (49.1 - 54.4) |

46.9 ± 1.59 (44.6 - 48) |

| BBC | 36.0 ± 1.44 (34.7 - 37.5) |

32.9 ± 0.54 (32.4 - 33.6) |

35.1 ± 0.90 (33.9 - 36.6) |

33.2 ± 1.62 (31.0 - 34.9) |

| HBC | 27.7 ± 0.55 (27.2 - 28.3) |

27.6 ± 0.38 (27.1 - 27.9) |

27.2 ± 0.58 (26.5 - 28.2) |

25.8 ± 0.63 (24.9 - 26.2) |

| MTR | 25.9 ± 0.22 (25.7 - 26.1) |

25.1 ± 0.56 (24.5 - 25.8) |

27.4 ± 0.78 (26.0 - 28.7) |

27.5 ± 0.56 (27 - 28.3) |

| CC | 15.7 ± 0.52 (15.4 - 16.3) |

14.9 ± 0.15 (14.7 – 15.0) |

16.4 ± 0.54 (15.5 - 17.1) |

15.6 ± 0.25 (15.4 - 15.9) |

| WPP | 12.1 ± 0.25 (11.8 - 12.3) |

11.8 ± 1.54 (10.6 – 14.0) |

11.8 ± 0.74 (10.8 - 12.8) |

10.9 ± 0.8 (10.5 - 12.1) |

| LPP | 10.9 ± 0.54 (10.3 - 11.4) |

9.7 ± 0.34 (9.2 - 9.9) |

11.9 ± 0.56 (11.0 - 12.7) |

11.2 ± 1.05 (9.7 - 12.3) |

| LAB | 11.7 ± 0.38 (11.4 - 12.1) |

11.2 ± 0.40 (10.9 - 11.8) |

12.3 ± 0.60 (11.2 - 13.3) |

12.5 ± 0.18 (12.3 - 12.7) |

| EAM | 2.7 (2.7 - 2.7) |

3.2 ± 0.16 (3.1 - 3.4) |

2.9 ± 0.29 (2.5 - 3.3) |

3.4 ± 0.05 (3.4 - 3.5) |

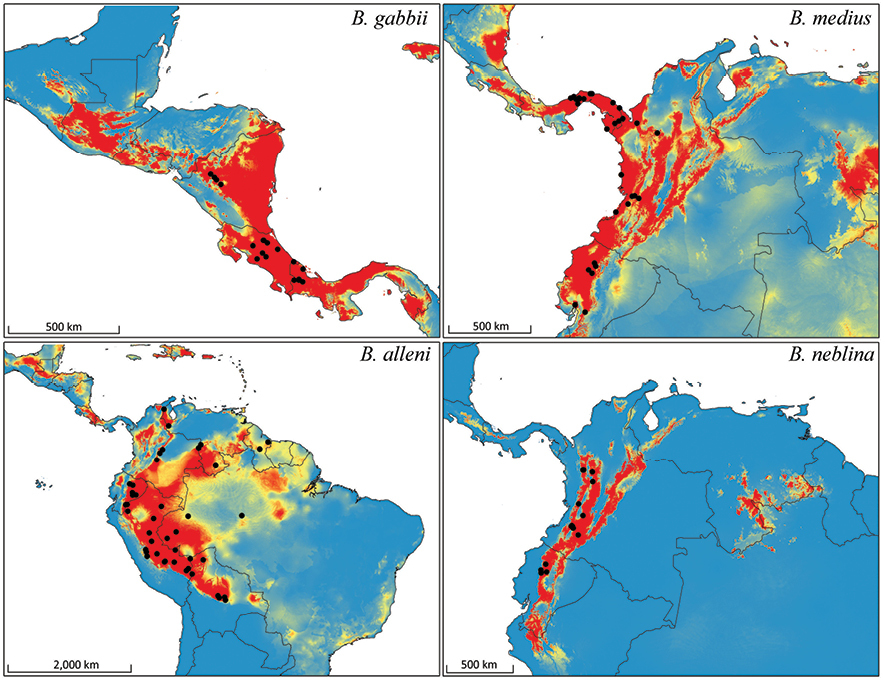

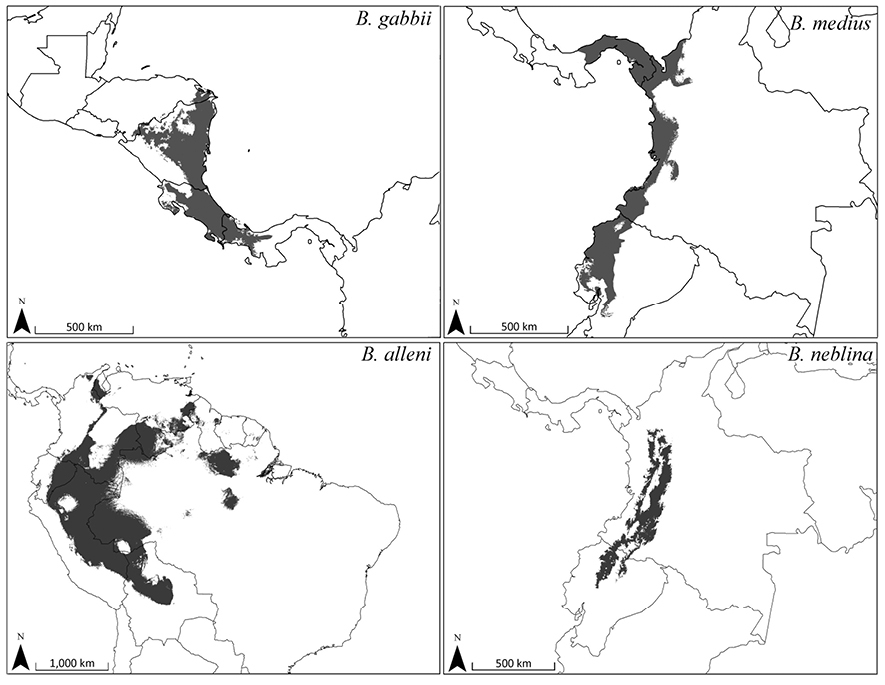

Distribution models for all species are judged to have performed well based on their high values for ‘area under the curve’ (AUC) and unregularized test gain (Table 9), as well as their fit of the final prediction to the locality data (Figures 11–12). There was relatively low impact of withholding test data from these models, as indicated by the low Mean Test AUC values. These values are lowest for Bassaricyon alleni, probably reflecting its larger distribution relative to the variation of environmental data (

Performance of bioclimatic distribution models for four Bassaricyon species using vouchered specimen localities. Mean values are averages of 10 models run, each withholding 20% of data as test localities, while the Full Model AUC used all available data. The mean value for equal training sensitivity and specificity was used as a logistic threshold to create a range map predicting presence/absence.

| Localities | Mean Test AUC (stdev) | Full Model AUC | Mean Unregularized Training Gain | Mean equal training sensitivity and specificity (logistic threshold) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bassaricyon alleni | 43 | 0.901 (0.036) | 0.939 | 1.85 | 0.302 |

| Bassaricyon gabbii | 18 | 0.977 (0.012) | 0.993 | 4.09 | 0.222 |

| Bassaricyon medius | 31 | 0.952 (0.028) | 0.988 | 3.76 | 0.119 |

| Bassaricyon neblina | 16 | 0.996 (0.002) | 0.998 | 4.77 | 0.160 |

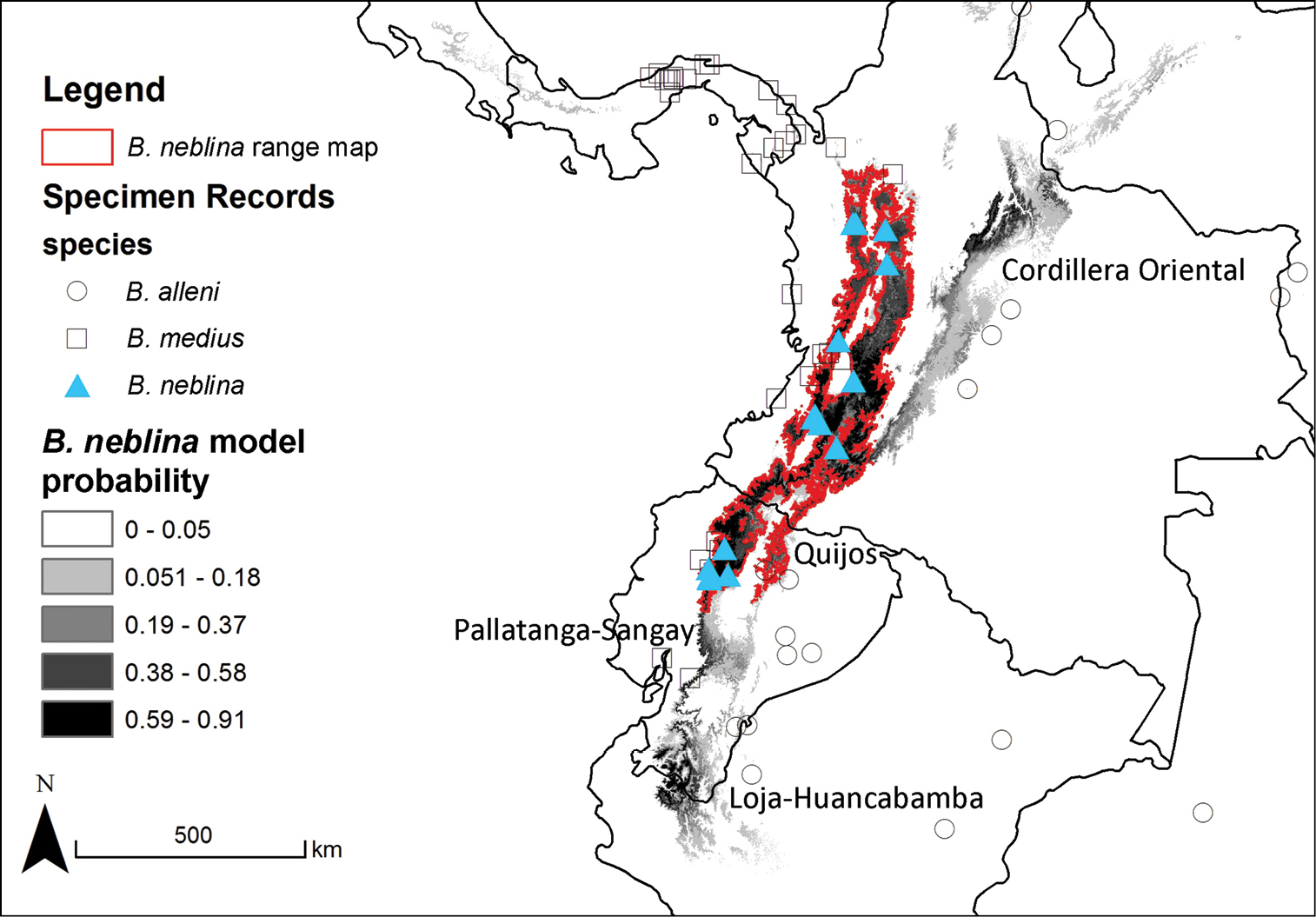

Bioclimatic distribution models and localities for Bassaricyon species. Models from MAXENT using all vouchered occurrence records, 19 bioclimatic variables, and one potential habitat variable.

Predicted distribution for Bassaricyon species based on bioclimatic models. To create these binary maps we used the average minimum training presence for 10 test models as our cutoff. In addition, we excluded areas of high probability that were outside of the known range of the species if they were separated by unsuitable habitat.

The full Maxent distribution models predict the suitability of habitat across South and Central America (Figure 11). To make the binary prediction maps (Figure 12) we excluded areas with high probability that were disjunct from areas where specimens have been recorded (e.g., western Venezuela excluded from the map for Bassaricyon neblina sp. n., central and eastern Brazil excluded from the Bassaricyon alleni map, northern Central America excluded from the Bassaricyon medius map, South America excluded from the Bassaricyon gabbii map). For Bassaricyon neblina sp. n. we excluded areas of high probability from the Eastern Cordillera of Colombia and the Andes of southern Ecuador and northern Peru because of the lack of specimens. Likewise, predicted suitable habitat for Bassaricyon gabbii in northern Central America (Honduras, Guatemala) remains unverified by specimen data. Although there are two recent unconfirmed records in the region (

The range of Bassaricyon neblina sp. n. is typical of many Andean species in being restricted to wet cloud forest habitats, which are limited in area and also under heavy development pressure. In comparing recent land use (

We designate as the holotype of neblina specimen number 66753 in the mammalogy collection of the American Museum of Natural History, New York, a skin and complete skull of an old adult female, from Las Máquinas (= Las Machinas [see

QCAZ 0159, partial skin, Otonga Reserve, 1800 m, Cotopaxi Province, Ecuador; MECN 2177, adult female, skin and skull, La Cantera 2300 m, Cotopaxi Province, Ecuador; QCAZ 8661, young adult female, skin, skull, and postcranial skeleton, Otonga Reserve, 2100 m, Cotopaxi Province, Ecuador (collected by K. Helgen et al., August 2006); QCAZ 8662, young adult female, skin, skull, and postcranial skeleton, [“forested gully near”] La Cantera, 2260 m, Cotopaxi Province, Ecuador (collected by M. Pinto et al., August 2006). We have also seen photographs of this species from Tandayapa, 2350 m, Pichincha Province (Figure 13).

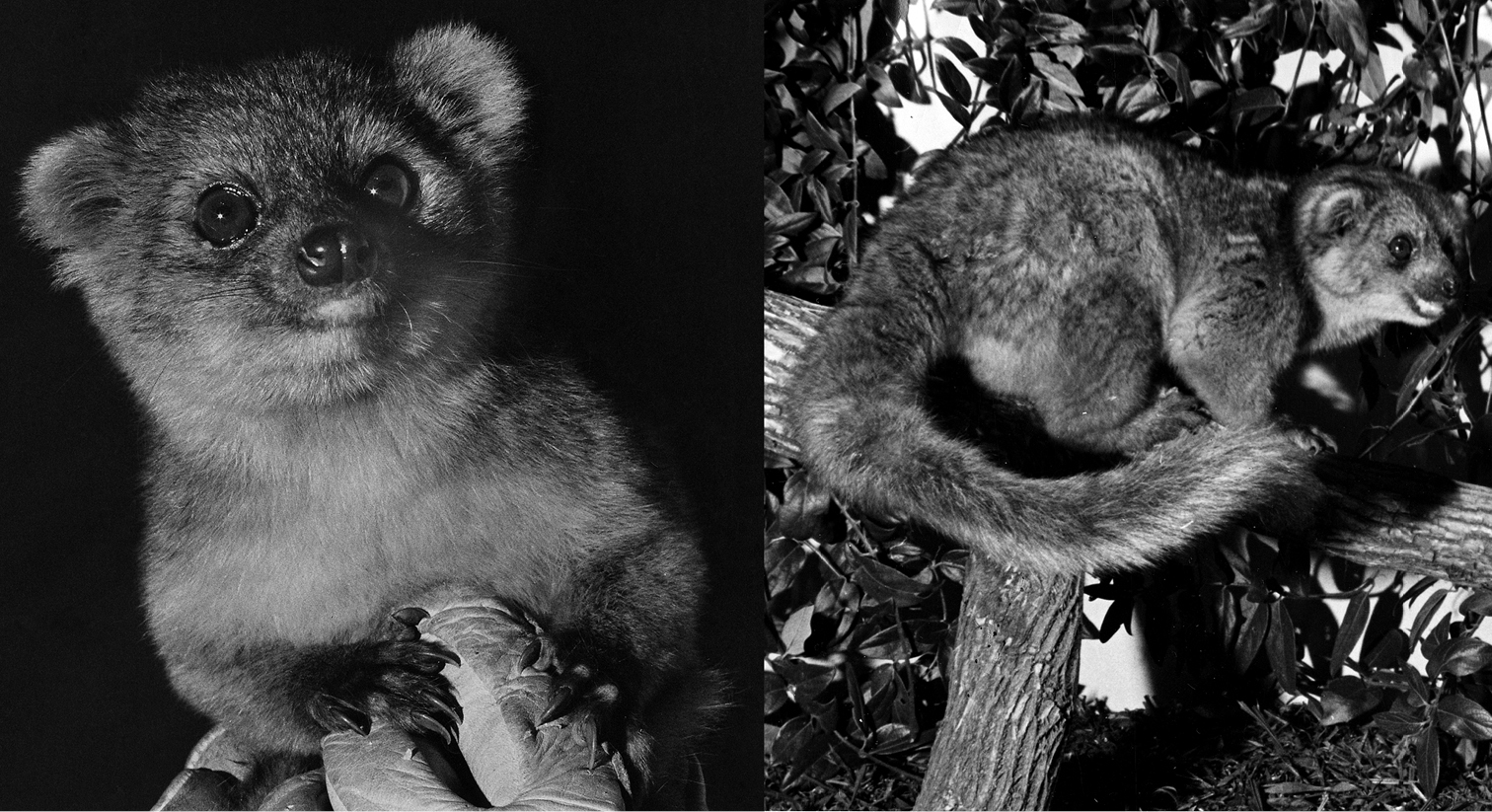

The Olinguito, Bassaricyon neblina neblina, in life, in the wild. Taken at Tandayapa Bird Lodge, Ecuador (for mammalogical background of Tandayapa, see

Below, we identify additional referred specimens when we describe three additional subspecies of Bassaricyon neblina from the cordilleras of Colombia (Figures 9–10, 13–16).

Olinguito skins from different regions of the Colombian Andes. Left, Bassaricyon neblina ruber, of the western slopes of the Western Andes of Colombia (FMNH 70722, adult male); Middle, Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi, of the eastern slopes of the Central Andes of Colombia (FMNH 70727, adult female); Right, Bassaricyon neblina osborni, of the eastern slopes of the Western Andes and eastern slopes of the Central Andes of Colombia (FMNH 90052, adult female).

The Olinguito, Bassaricyon neblina osborni, in life. Photograph taken in captivity, at the Louisville Zoo (see

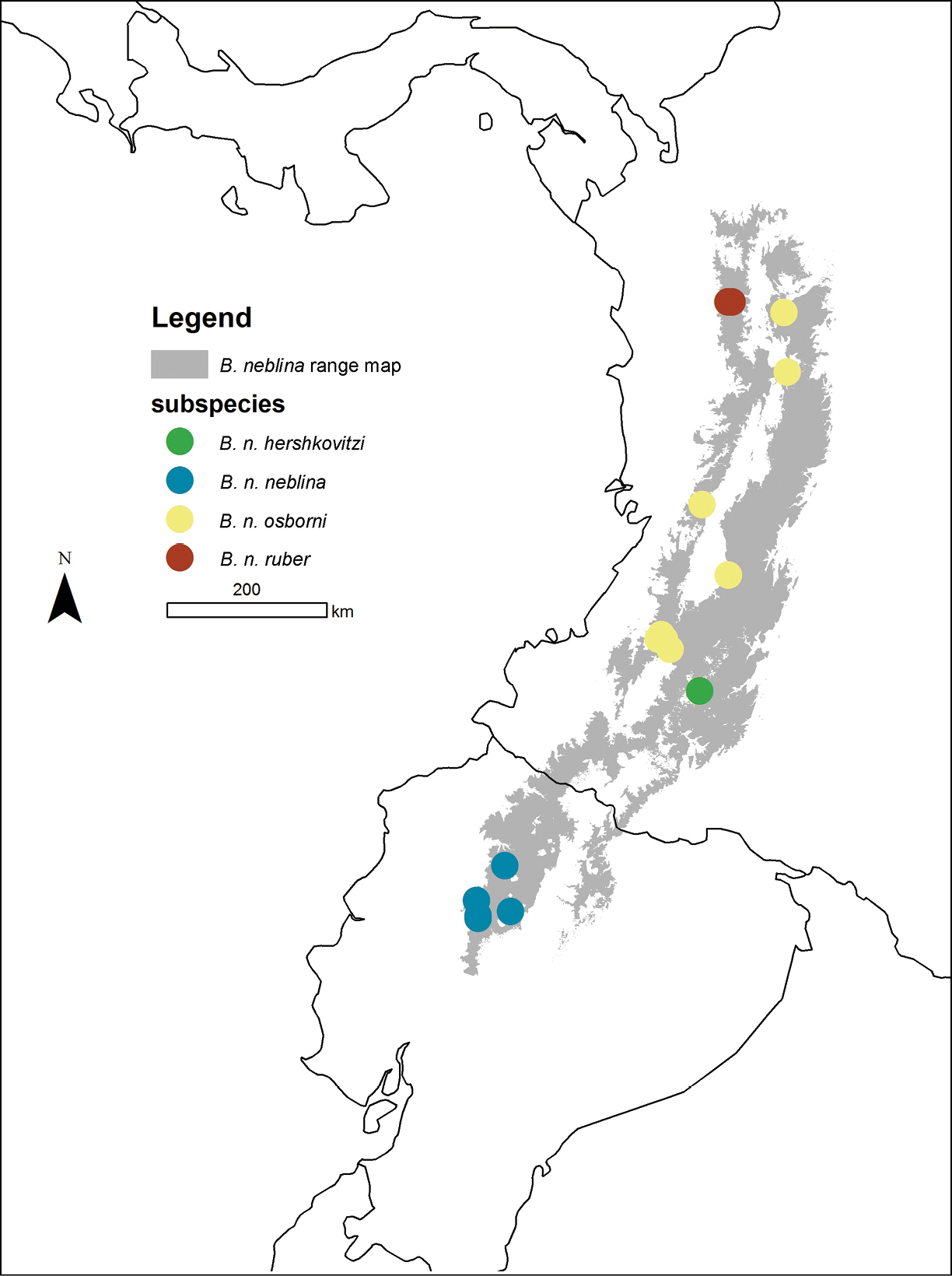

Distributions (localities) of the four Olinguito subspecies in the Andes of Colombia and Ecuador.

Bassaricyon neblina can be easily identified on the basis of both external and craniodental characteristics (Figures 3–7, Tables 3–5). It differs from other Bassaricyon in its smaller body and cranial size; longer, denser, and more richly coloured dorsal pelage (black-tipped, tan to strikingly orange- to reddish-brown); indistinctly banded, bushier, and proportionally shorter tail (at least compared to the lowland olingos, Bassaricyon alleni and Bassaricyon medius, Table 5); (externally) more rounded face with a blunter, less tapering muzzle; smaller and more heavily furred external ears, and considerably reduced auditory bullae, with a markedly smaller external auditory meatus; broadened and more elongate postdental palate (‘palatal shelf’), bearing more prominent lateral ‘flanges’ (sometimes developed to the point where it nearly closes off the “palatal notch” sensu

Where Bassaricyon medius and Bassaricyon neblina occur in regional sympatry on the western slopes of the Andes, Bassaricyon neblina is smaller and more richly rufous and/or blackish in coloration, and is distinguished by all of the characteristics noted above. Externally, Bassaricyon neblina can only be confused with the highest elevation populations of Bassaricyon alleni, from forests above 1000 m on the eastern slopes of the Andes (specimens from Pozuzo and Chanchamayo in Peru), which, like Bassaricyon neblina, also have long, black-tipped dorsal pelage (though not so strongly rufous as in Bassaricyon neblina), ears that are especially furry (though not so small as in Bassaricyon neblina), and tails averaging slightly shorter than in lowland populations of Bassaricyon alleni (but not as short as in Bassaricyon neblina). The craniodental characteristics of Bassaricyon neblina (especially of the palate, bullae, and molars) are unmistakable.

The specific epithet neblina (Spanish, “fog or mist”), a noun in apposition, references the cloud forest habitat of the Olinguito.

The recorded distribution of Bassaricyon neblina comprises humid montane rainforests (“cloud forests”) from 1500 m to 2750 m in the Northern Andes, specifically along the western and eastern slopes of the Western Andes of Colombia and Ecuador, and along the western and eastern slopes of the Central Andes of Colombia (Figure 16). Bassaricyon neblina occurs in regional sympatry with Bassaricyon medius medius on the western slopes of the Ecuadorian Andes, where we have encountered the two species at localities less than 5 km apart. On the basis of our museum and field research, we document Bassaricyon neblina from 16 localities (representing 19 elevational records) in the Western Andes of Ecuador and the Western and Central Andes of Colombia. All sites are situated between 1500 and 2750 m (mean 2100 m, median 2130 m, ± 280 s.d.) and are associated with humid montane forest (“cloud forest”,

Geographic variation in the Olinguito is remarkable, reflecting consistent regional differences in color, size, and craniodental features associated with differential distributions in disjunct areas of the Andes. This is unsurprising given that the montane forests of the Central and Western Cordilleras of the Northern Andes are a region where major evolutionary differentiation has unfolded in many endemic Andean vertebrate groups (e.g.,

This subspecies is (in skull length) smaller than Bassaricyon neblina osborni subsp. n., but larger than Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi subsp. n. and Bassaricyon neblina ruber subsp. n. (though Bassaricyon neblina ruber subsp. n. is more robust cranially, with a wider skull). It has proportionally very large teeth, especially P4 and the first molars, and a narrow skull, with a narrow and low-domed braincase (Figures 9–10, Table 8). In color it most closely resembles Bassaricyon neblina osborni subsp. n., but is the least rufous of the subspecies, usually with the greatest preponderance of black tipping to the fur (e.g., Figure 13).

The nominate subspecies is endemic to Ecuador, where it is recorded from the western slopes of the Andes, in Pichincha and Cotopaxi Provinces, in forests at elevations from 1800 to 2300 m (Figure 16).

As listed for Bassaricyon neblina, above.

This is the largest subspecies of Bassaricyon neblina, with a short rostrum, widely splayed zygomata, wide rostrum and braincase, and very large molars and posterior premolars; the dorsal pelage is of moderate length, tan to orangish-brown in overall color, with prominent black and gold tipping, with a more grayish face and limbs, with the limbs bearing relatively short fur, and a tail usually grizzled with golden-brown fur tipping.

This is the representative of Bassaricyon neblina on the eastern slopes of the Western Andes of Colombia (e.g., Castilla Mountains [AMNH]; Sabanetas [FMNH]; El Tambo [NMS]; the vicinity of Cali [

Records to date of Bassaricyon neblina osborni are from 1500 to at least 2750 m elevation in Cauca, Valle del Cauca, and Antioquia Departments of Colombia (Figure 16). Bassaricyon medius medius is also recorded from the Cauca Valley (east slopes of Western Andes and western slopes of Central Andes) at elevations up to at least 725 m (UV-3774:

The name honors Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857–1935), paleontologist, faculty of Princeton and Columbia Universities, and Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology (1891–1909) and President (1909–1933) of the American Museum of Natural History (

FMNH 88476, adult male, skin and skull, Munchique, 2000 m, Cauca Department, Colombia (collected by K. von Sneidern, 3 June 1957).

AMNH 32608, adult female, skin and skull, and AMNH 32609, adult male, skin and skull, Gallera (

AMNH 14185, skin (skull not found), adult male, Castilla Mountains (“La Castilla” of

This is the smallest subspecies of Bassaricyon neblina, with the fur of the dorsum and tail very long, and richly orange-brown (brown with strong golden and black tipping) in coloration, and more golden brown face and limbs, with the limbs well-furred. The skull, braincase, and rostrum are especially narrowed, the posterior palatal shelf is extremely broad, and the molars are proportionally very large.

This is the representative of Bassaricyon neblina on the eastern slopes of the Central Andes of southern Colombia (Figure 16). Records to date are from 2300 to 2400 m elevation in the vicinity of San Antonio (Huila Department), a forested locality “on eastern slope of Central Andes at headwaters of Rio Magdalena, near San Agustin” (

The name honors American mammalogist Philip Hershkovitz (1909–1997), collector of the type series, Curator of Mammals at the Field Museum of Natural History (1947–1974; Emeritus Curator until 1997), and authority on South American mammals (

FMNH 70727, adult female, skin, skull, and postcranial skeleton, San Antonio, 2300 m, San Agustin, Huila Department, Colombia (collected by P. Hershkovitz, 6 September 1951) (see Figure 18).

FMNH 70724, adult male, skin, skull, and postcranial skeleton, San Antonio, 2400 m, San Agustin, Huila Department, Colombia (collected by P. Hershkovitz, 20 August 1951); FMNH 70725, adult male, skin, skull, and postcranial skeleton, San Antonio, 2400 m, San Agustin, Huila Department, Colombia (collected by P. Hershkovitz, 25 August 1951); FMNH 70726, adult male, skin, skull, and postcranial skeleton, San Antonio, 2300 m, San Agustin, Huila Department, Colombia (collected by P. Hershkovitz, 6 September 1951).

This subspecies is markedly smaller (at least in skull length) than Bassaricyon neblina neblina and Bassaricyon neblina osborni, with the fur longest and most strikingly reddish of all the Olinguito populations (reddish with golden and black tipping), and more golden brown face and and reddish brown limbs, with the limbs well-furred. Though similar in overall skull length to Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi, the skull is especially wide for its size (Table 8), with broad zygomata, braincase, and rostrum compared to that subspecies.

This subspecies is recorded from the Urrao District of Colombia (2200–2400 m in Huila and Antioquia Departments), on the western slope of the Western Andes, where it is documented by specimens collected in 1951 by Philip Hershkovitz.

The name refers to the rich reddish-brown pelage of this subspecies (Figures 3, 14).

FMNH 70722, adult male, skin, skull, and postcranial skeleton, Rio Urrao, 2400 m, Urrao, Huila Department, Colombia (collected by P. Hershkovitz, 24 April 1951).

FMNH 70721, adult female, skin, skull, and postcranial skeleton, Rio Ana, 2200 m, Urrao, Huila Department, Colombia (collected by P. Hershkovitz, 19 April 1951); FMNH 70723, adult male, skin, skull, and postcranial skeleton, Guapantal, 2200 m, Urrao, Antioquia Department, Colombia (collected by P. Hershkovitz, 28 April 1951).

Information from sympatric occurrences and captive breeding demonstrates that the Olinguito, Bassaricyon neblina, is reproductively isolated from other species of Bassaricyon and clearly constitutes a distinct “biological species” (i.e., sensu

In Ecuador we documented the Olinguito (Bassaricyon neblina neblina) in regional sympatry with the Western lowland olingo, Bassaricyon medius medius; we recorded the two species at localities less than 5 km apart (i.e., at Otonga and San Francisco de las Pampas) during fieldwork in August 2006. The ecogeographic relationship between the two species is probably one of elevational parapatry or limited elevational overlap along the western slopes of the Andes. Bassaricyon medius medius extends into the elevational range of Bassaricyon neblina, perhaps especially in areas where cloud forests have been cleared for human settlement, agriculture, and pastoralism (Figure 17).

Area of sympatric occurrence between Bassaricyon species in western Ecuador. Farmland cutting into cloud forest habitat at Las Pampas, approximately 1800 m, on the western slopes of the Western Andes, Ecuador, along the boundary of Otonga, a protected forest reserve. It is at this elevational and environmental boundary that Bassaricyon medius medius (lower elevations, including more anthropogenically disturbed habitats) and Bassaricyon neblina neblina (higher elevations, less disturbed forests) co-occur in regional sympatry on the western slopes of the Andes.

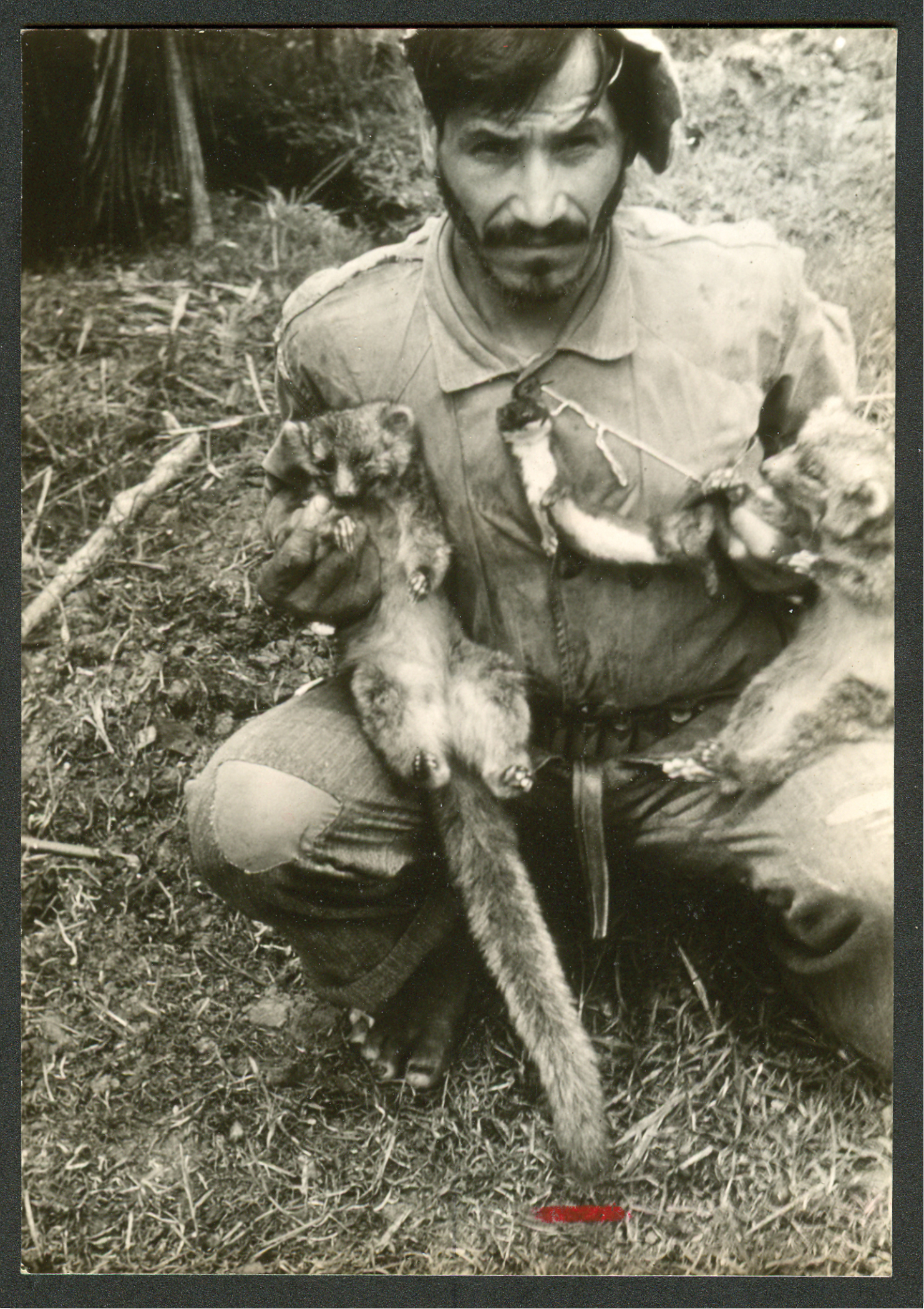

Type series of an Olinguito subspecies, Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi, in the field. Two Olinguito specimens (FMNH 70726, paratype of hershkovitzi, and FMNH 70727, holotype of hershkovitzi, along with a Long-tailed weasel, Mustela frenata, FMNH 70998) brought in by a local hunter, 6 September 1951, at San Antonio, San Agustín, Huila District, Colombia. Photo by P. Hershkovitz, courtesy of the Field Museum of Natural History.

Ingeborg Poglayen-Neuwall (pers comm. to R. Kays, 2006) informed us that an adult female zoo animal named “Ringerl” (Figure 15; also figured by

The Olinguito differs from congeners (Bassaricyon alleni, Bassaricyon medius, and Bassaricyon gabbii) by 9.6–11.3% in base-pair composition of the (mitochondrial) cytochrome b gene (Table 2), a level of divergence consistent with that separating biological species in many groups of mammals, including carnivores (

Karyotype: The karyotype of an adult female Olinguito(Bassaricyon neblina osborni, then identified as “Bassaricyon gabbii”, with 2n = 38, as in all procyonids) was reported and discussed (but not described in detail) by

Description: The Olinguito is the smallest species of Bassaricyon, both in skull and body size (Tables 3, 5), and is thus, on average, the smallest living procyonid (matched only by small individuals of the Ringtail, Bassariscus astutus). The tail averages 10% longer than the head-body length (Table 5). The pinnae are proportionally much smaller in Bassaricyon neblina than in other Bassaricyon, appearing shorter and rounder, and standing out less conspicuously on the head; they are also more heavily furred and usually fringed with a paler, contrasting border of buffy or golden fur. The dorsal fur is dense, long, and luxurious, with the longer hairs measuring 30–40 mm in length (usually much shorter in other Bassaricyon, at least in the predominantly lowland taxa Bassaricyon medius and Bassaricyon alleni, but reaching 25 mm in the highest-elevation populations of Bassaricyon alleni on the eastern versant of the Andes). The hairs of the dorsum, crown, upper limbs, and tail are golden-orange, with grey bases and dark red-brown or blackish-brown tips, generating a distinctly dark, often red-brown appearance, more striking than the relatively drab fur colors (more tan or yellowish-brown to grayish-brown) of other Bassaricyon (Figure 3). The fur of the cheeks, chin, venter, and underside of the limbs is yellow to the bases, often washed with orange. The fur of the face in front of the eyes is shorter and gray or buff with black tipping, sometimes with a pale cream ring around the eyes. The hairs of the tail are strongly tipped with gold, or with both golden and blackish-brown tipping. In contrast to specimens of other Bassaricyon, the tail is not conspicuously banded, though when viewed in the right light, a banding pattern of alternating golden and brown hues is weakly apparent in some specimens. A white terminal tail tip is present in a minority of individuals.

Like other Bassaricyon, the cranium of Bassaricyon neblina is long relative to its width, with a moderately long and broad rostrum, an elongate and somewhat globose braincase with a smooth dorsal surface, and moderately developed postorbital processes.

In Bassaricyon neblina, the temporal ridges do not meet to form a sagittal crest, even in older animals. The postdental palate is usually flared laterally, but is smoothly parallel-sided, tapers posteriorly, or bears only weaker bony flaring in other Bassaricyon (Figures 4–7, 19). At its more extreme development (e.g., in FMNH 70726), the portion of the bony palate sitting behind M2 is almost continuously joined to the postdental palate by a continuous shelf of bone, rather than bearing a deep excavation separating the molar-bearing portion of the bony palate from the postdental shelf (Figure 19). The auditory bullae are very small in the Olinguito relative to other Bassaricyon, both in length and vertical inflation, and the external auditory meatus is considerably narrower in diameter, on average (Figures 4–7). The median septal foramen of the anterior palate (Steno’s Foramen), between the paired incisive (or anterior palatal) foramina, is usually well-developed. The mandible is proportionally less elongate than in other Bassaricyon, with a proportionally larger and more vertically-oriented coronoid process (Figures 4–5). The first two upper premolars are caniniform, similar in size and shape to those of other Bassaricyon. P3 is usually relatively smaller in Bassaricyon neblina than in other Bassaricyon. P4 is similar in structure to congenersbut is relatively larger with a more bulbous protocone and more prominent metacone. M1 and M2 are proportionally lengthened and considerably more massive in appearance, especially relative to skull size, than in other Bassaricyon. p4 is variable in size among Bassaricyon neblina subspecies, generally smaller than other Bassaricyon in Bassaricyon neblina ruber and Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi, but proportionally quite large in Bassaricyon neblina neblina. m1 is relatively much larger in Bassaricyon neblina than in other Bassaricyon;each of the four major cusps that define the subrectangular shape of this tooth are massive and bulbous, and the posterior portion is especially broadened, with the metaconid and hypoconid particularly large and laterally expanded relative to congeners. m2 is also often expanded in size in Bassaricyon neblina relative to other Bassaricyon.

Lateral flare of the postpalatal shelf in Bassaricyon. Lateral extension of the postpalatal shelf (shown by white arrows) is usually absent or little-developed in other Bassaricyon (e.g., left, Bassaricyon alleni, FMNH 41501), but is well-developed in Bassaricyon neblina (e.g., center, Bassaricyon neblina ruber, FMNH 70721, and right, Bassaricyon neblina hershkovitzi, FMNH 70726).

Natural history: Our field observations document that Bassaricyon neblina is nocturnal, arboreal, frugivorous, and probably largely solitary (compiled during July and August 2006 at Otonga Forest Reserve in Ecuador: 00°41’S, 79°00’W; for faunal and floral context see

An adult female Olinguito (an animal named “Ringerl”, Bassaricyon neblina osborni, Figure 15) that lived at the Louisville Zoological Park and the National Zoological Park in Washington during 1967–1974 made vocalizations different from those of other Bassaricyon according to

Previous identifications and references:

Though described taxonomically for the first time in this paper, the Olinguito (heretofore misidentified as other species of Bassaricyon) has been represented in museum collections for more than a century, has been exhibited in zoos, has had its karyotype published, and has been included in published molecular phylogenetic studies.

Olinguito museum specimens previously reported in the literature include specimens from Gallera, Colombia, mentioned by

Molecular data for Bassaricyon neblina from a cell line were first generated and used in a phylogenetic study of carnivore relationships by

http://species-id.net/wiki/Bassaricyon_gabbii

Northern OlingoThe holotype of gabbii is USNM A14214, an unsexed adult skull (with dimensions, in this sexually dimorphic species, that indicate that the specimen is female). The holotype skull, collected by William Gabb, was figured by

The holotype of richardsoni is AMNH 28486, an adult female (skin and skull), from “Rio Grande (altitude below 1, 000 feet), Atlantic Slope”, Nicaragua (

The holotype of lasius is UMMZ 64103, an adult male (skin and skull), from “Estrella de Cartago… six to eight miles south of Cartago near the source of the Rio Estrella, … about 4500 feet”, Costa Rica (

The holotype of pauli is ANSP 17911, an adult male (skin and skull), from “between Rio Chiriqui Viejo and Rio Colorado, on a hill known locally as Cerro Pando, elevation 4800 feet, about ten miles from El Volcan, Province de Chiriqui”, Panama (

This is the largest olingo, measuring larger than all other taxa in most measurements, and is the most sexually dimorphic species of Bassaricyon in cranial characters and measurements (Table 3). It can be distinguished externally from other olingo species by its coloration, which is grayish-brown (less rufous than in other Bassaricyon), with the face usually dominated by gray, the belly fur cream-colored (sometimes washed with orange), and the tail showing a faint banding pattern (Figures 3, 20). Fur length on the dorsum varies noticeably with elevation (longer at higher elevation). The tail is similar in length to the head-body length, averaging shorter relative to total length than in other olingos (Table 5), perhaps an indication of less complete arboreal habits than in other Bassaricyon (an aspect unfortunately not captured well in our Figure 3).

Northern Olingo, Bassaricyon gabbii, in life, in the wild. Photographed at Monteverde, Costa Rica by Greg Basco (left) and Samantha Burke (right).

The skull is large compared to other Bassaricyon (Table 3), with the zygomata more widely splayed, particularly in males (Figures 4–5, Table 3), and a wide rostrum. Uniquely in Bassaricyon, a sagittal crest develops in older males. The cheekteeth and auditory bullae are proportionally quite small compared to the size of the skull, relatively smaller than in Bassaricyon medius and Bassaricyon alleni, and the postpalatal shelf tends to be broadened relative to Bassaricyon medius and Bassaricyon alleni. The canines are more massive than in other Bassaricyon. The first lower molar (m1) is distinctively shaped relative to other Bassaricyon, with the paraconid usually situated right at the midpoint of the front of the tooth and often jutting out anteriorly (the m1 paraconid is less prominent and/or situated more antero-medially in other Bassaricyon).

This species occurs in the central portion of Central America, in montane and foothill forests, from northern Nicaragua to Costa Rica and into the Chiriqui Mountains in western Panama, possibly also extending north into Honduras and Guatemala (

There are unverified records of olingos occurring north of Nicaragua, in Honduras and Guatemala, and these records may represent Bassaricyon gabbii.

The nominal taxa richardsoni, lasius, and pauli, synonymized here with Bassaricyon gabbii, were all originally diagnosed based on distinctions in pelage coloration and fur length, in small samples (

Specimens from northern Nicaragua have fur that is slightly more suffused with orange tones than animals from Costa Rica or western Panama. Nicaraguan populations may deserve recognition as a distinct subspecies, Bassaricyon gabbii richardsoni, as sometimes classified (e.g.,

This is the olingo speciesmost commonly seen and photographed by visitors to the Neotropics, especially because it is present at Monteverde and several other protected areas in Costa Rica that are frequently visited by both tourists and biologists (e.g.,

Costa Rica: AMNH 140334, LACM 26480, 64837, UMMZ 64103 (holotype of lasius), 112321, 112322, USNM A14214 (holotype of gabbii). Nicaragua: AMNH 28486 (holotype of richardsoni), 30748, 30749, USNM 337632, 338859. Panama: AMNH 147772, ANSP 17911 (holotype of pauli), 18850, 18851, 18852, 18893, 18894, BMNH 3.12.6.3, 5.5.4.5, KU 165554, MCZ 38506, TCWC 12941, USNM 316230, 324293, 324294, 516945, 516946.

http://species-id.net/wiki/Bassaricyon_alleni

Eastern Lowland OlingoThe holotype of alleni is BMNH 80.5.6.37, an adult female (skin and skull), from “Sarayacu, on the Bobonasa River, Upper Pastasa River …this must not be confused with the far larger and better known Sarayacu on the Ucayali in Peru”, in Amazonian Ecuador (

The holotype of beddardi was an adult female, from “Bastrica Woods, Essequibo River”, Guyana (

The holotype of siccatus is BMNH 27.5.3.2, an adult female (skin and skull), from “Guaicaramo, on the Llanos of Villavicencio, east of Bogata, about 1800 feet”, Colombia (

Bassaricyon alleni is a medium-sized olingo, smaller than Bassaricyon gabbii of Mesoamerica, and larger than Bassaricyon neblina of the Andes. It requires closest comparison with the closely-related and allopatrically-distributed taxon Bassaricyon medius, from which it differs especially in having (externally) more strikingly black-tipped dorsal pelage (giving the pelage a slightly darker appearance in Bassaricyon alleni), (cranially) in its proportionally wider and (on average) shorter rostrum, and in having more inflated auditory bullae (Table 3), and (dentally) in its generally larger p4 (Table 4). Bassaricyon alleni is considerably larger than Bassaricyon medius medius (of South America west of the Andes), such that there is a clear body size contrast between the two lowland olingo taxa of South America (Bassaricyon alleni east of Andes vs. B. medius medius west of Andes), but is very similar in size to Bassaricyon medius orinomus (of eastern Panama). Bassaricyon medius orinomus often has a reddish tail that contrasts somewhat with the less rufous head and body; Bassaricyon alleni tends to be more uniformly colored head to tail. In life, Bassaricyon alleni usually has a darkly pigmented nose, whereas in Bassaricyon medius the nose is often pink (Ivo Poglayen-Neuwall to C.O. Handley Jr., in litt., 9 February 1973; Figures 21–22). Sequence divergence in cytochrome b in these sister species (Bassaricyon alleni, Bassaricyon medius), separated by the Andes, is 6–7% (Table 2).

Eastern Lowland Olingo, Bassaricyon alleni, in life, in the wild. Top, photographed at night (accentuating the dark tones in the pelage) at La Esperanza (Distrito de Yambrasbamba, Provincia de Bongará, Departamento Amazonas), 2000 m, northern Peru; Middle, color camera trap photo in forest canopy, from confluence of the Camisea and Urubamba Rivers (11°42'S, 72°48'W). Peru; Bottom, infrared camera trap photo in forest canopy (same locality as middle photo), showing an olingo carrying a baby in its mouth. Top photograph by César M. Aguilar; middle and bottom camera trap photos courtesy of Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.

Western Lowland Olingo, Bassaricyon medius medius, in life. A wild animal photographed under studio conditions at Las Pampas, adjacent to Otonga Reserve, Ecuador. Photographs courtesy of P. Asimbaya and L. Velásquez.

This is the only species of Bassaricyon found east of the Andes. Bassaricyon alleni has a wide distribution in forests on the eastern slopes of the Andes and in lowland forests east of the Andes, with records from forested areas of Venezuela (

In Guyana, Bassaricyon alleni is recorded only from two specimens, the type of beddardi (

In Brazil, the only firm records are from southwestern Amazonia (the states of Amazonas and Acre) (

The elevational range of Bassaricyon alleni as documented by museum specimens extends from sea level to 2000 m. The great majority of records originate from lowland forests below 1000 m, but specimens from Ecuador and Peru (especially from Chanchamayo) have been collected from 1100 to 2000 m (specimens at BMNH, FMNH, USNM). It seems likely that the distribution of Bassaricyon alleni extends higher on the eastern slopes of the Andes than that of Bassaricyon medius does on the western slopes because of the apparent absence of Bassaricyon neblina on the eastern versant of the Andes.

The karyotype of a male Bassaricyon alleni (2n = 38, NF = 68; then identified as “Bassaricyon gabbii”) was reported and described by

Some geographic variation is apparent in Bassaricyon alleni, and several taxonomic names have been applied to different regional representatives of this species, including in the western Amazon (typical alleni

The most notable morphological distinction that we have observed within Bassaricyon alleni is between lowland specimens (from forests below 1000 m) and specimens collected in montane forests above 1000 m in the Eastern Andes (e.g., Chanchamayo and Pozuzo in Peru). Specimens from these higher elevations have somewhat shorter tails and are more brownish (less orange tones in pelage), with notably longer fur, and greater development of black tipping to the fur, though the pelage is not as long and luxurious as in Bassaricyon neblina. Press reports of a possibly new species of Bassaricyon discovered in the Tabaconas – Namballe National Sanctuary in the Eastern Andes of Peru (e.g.,

Bassaricyon beddardi of Guyana has often been recognized as a species distinct from Bassaricyon alleni in checklists and inventories (e.g.,

Though this is the most widely distributed member of the genus (Figure 12), relatively little is known of this species in the wild. Brief notes about the ecology and behavior of wild Bassaricyon alleni are included in the publications of

Colombia: AMNH 70532, 142223, BMNH 27.5.3.2 (type of siccatus), USNM 281482, 281483, 281484, 281485, 395837, 544415. Ecuador: AMNH 67706, BMNH 14.4.25.38, 80.5.6.37 (holotype of alleni), EPN “4”, RM0151, FMNH 41501, 41502, MCZ 37920, 37921, 37922, 37923, QCAZ 3371, YPM 1458, 1459. Guyana: ROM 107380. Peru: AMNH 98653, 98654, 98662, 98709, BMNH 5.11.2.6, 27.1.1.70, 1912.1.15.3, 1922.1.1.17, FMNH 34717, 65787, 65789, 65805, 86908, 86909, 98709, MVZ 153646, 155219, 155220, UMMZ 107907, USNM 194315, 194316, 255121, 255122, ZMB 63197. Venezuela: BMNH 99.9.11.25, USNM 443279, 443717, 443718.

http://species-id.net/wiki/Bassaricyon_medius

Western Lowland OlingoThe holotype of medius is BMNH 9.7.17.10, an adult male (skin and skull) from “Jimenez, mountains inland of Chocó, W. Colombia, 2400 feet” (

The holotype of orinomus is USNM 179157, an adult male (skin and skull), from “Cana (altitude 1, 800 feet), in the mountains of eastern Panama” (

Bassaricyon medius is a medium-sized olingo, smaller (on average) than Bassaricyon gabbii of Mesoamerica and larger than Bassaricyon neblina of the Andes. It requires closest comparison with the closely-related, allopatrically-distributed taxon Bassaricyon alleni, from which it differs especially in having (externally) less strikingly black-tipped dorsal pelage (which gives the pelage a slightly darker appearance in Bassaricyon alleni), (cranially) in its proportionally narrower and (on average) longer rostrum, and in having less inflated auditory bullae (Table 3), and (dentally) in its generally smaller p4 (Table 4). Bassaricyon medius medius is considerably smaller than Bassaricyon alleni (of South America east of the Andes), such that there is a clear body-size contrast between the two lowland olingo taxa of South America (Bassaricyon alleni east of Andes vs. B. medius medius west of Andes), but Bassaricyon medius orinomus (of eastern Panama and northwestern Colombia) is very similar in size to Bassaricyon alleni. Bassaricyon medius orinomus often has a reddish tail that contrasts somewhat with the less rufous head and body; Bassaricyon alleni tends to be more uniformly colored head to tail. In life, Bassaricyon alleni usually has a darkly pigmented nose, whereas in Bassaricyon medius the nose is often pink (Ivo Poglayen-Neuwall to C.O. Handley Jr., in litt., 9 February 1973; Figures 21–22). Sequence divergence in cytochrome b in these sister species (Bassaricyon medius, Bassaricyon alleni), separated by the Andes, is 6–7% (Table 2).

Bassaricyon medius occurs in forests from Central Panama to Colombia and Ecuador west of the Andes, where it is recorded from sea level up to about 1800 m elevation. We recognize two distinctive subspecies of Bassaricyon medius, distinguished especially by clear differences in size (Tables 6–7).

Bassaricyon medius medius (Figure 22) occurs in most of the South American portion of the range, where it is recorded west of the Andes in western Colombia (

Bassaricyon medius orinomus (Figure 23) occurs primarily in the Central American portion of the range, where it is recorded from central and eastern Panama, from the vicinity of the Canal Zone in the west to the Darien Mountains in the east (

Western Lowland Olingo, Bassaricyon medius orinomus, in life. Wild animals captured, radio-collared, released, and studied by Roland Kays in Limbo Plot, Pipeline Road, Gamboa, Panama (

As noted above for Bassaricyon gabbii, the nature of interactions with the distribution of Bassaricyon gabbii on the western margin of the range of Bassaricyon medius in Panama (whether characterized by allopatry, parapatry, or sympatry) is unknown and worthy of study.

The first detailed description of representatives of this species was published in French by

Relevant field notes associated with Bassaricyon medius include: “shot at dusk in high tree in forest” (FMNH 29180); “shot at 8 pm, 40 feet up in large tree, active and agile, but curious, eyes shine brightly” (USNM 305748); “shot at 8:30 pm in avocado plantation” (USNM 305749); “shot near banana plantation (at night), stomach with banana” (USNM 305750); ” “shot at 8:30 pm in large tree in cafetal [coffee plantation], stomach with soft fruit with tomato-like seed” (USNM 305751); “shot at 8 pm in forest” (USNM 307037); “lactating” and pregnant with “1 embryo”, “stomach: fruit pulp” (USNM 310666); “shot in tree at night” (USNM 335767, 338348); “shot at night in tree in forest” (USNM 335769); “shot at night in tree in cocoa grove” (USNM 335770); “shot in small tree in plantain patch at night” (USNM 335771); “one embryo” in a pregnant female “shot in forest” (USNM 363342); “shot in banana tree” (USNM 363343)

Bassaricyon medius medius

Colombia: BMNH 9.7.17.10 (holotype of medius), 9.7.17.11, FMNH 29180, 86852, 90049, 90051, MVZ 124112, USNM 598997. Ecuador: AMNH 66752, BMNH 34.9.10.81, 34.9.10.82, EPN 841, 900, MECN DAP37, NMS A59-5081, A59-5082, QCAZ 8758, 8659.

Bassaricyon medius orinomus