(C) 2012 Kristofer M. Helgen. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

The monotreme genus Zaglossus, the largest egg-laying mammal, comprises several endangered taxa today known only from New Guinea. Zaglossus is considered to be extinct in Australia, where its apparent occurrence (in addition to the large echidna genus Megalibgwilia) is recorded by Pleistocene fossil remains, as well as from convincing representations in Aboriginal rock art from Arnhem Land (Northern Territory). Here we report on the existence and history of a well documented but previously overlooked museum specimen (skin and skull) of the Western Long-Beaked Echidna (Zaglossus bruijnii) collected by John T. Tunney at Mount Anderson in the West Kimberley region of northern Western Australia in 1901, now deposited in the Natural History Museum, London. Possible accounts from living memory of Zaglossus are provided by Aboriginal inhabitants from Kununurra in the East Kimberley. We conclude that, like Tachyglossus, Zaglossus is part of the modern fauna of the Kimberley region of Western Australia, where it apparently survived as a rare element into the twentieth century, and may still survive.

Extinction, Kimberley, monotreme, Pleistocene survival, rock art, Zaglossus

The egg-laying mammals, or monotremes (Monotremata), are the sister group to all other extant mammals and are known as living animals only from the Australian continent, incorporating the modern landmasses of Tasmania, Australia, and New Guinea, which share a continental shelf that is periodically united during times of lowered sea levels as a single continuous landmass (“Sahul” or “Meganesia”). There are two extant monotreme families. The platypus, Ornithorhynchidae, is represented by a single living genus and species, Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw, 1799), a semi-aquatic monotreme distributed throughout eastern Australia from tropical Queensland south to Tasmania and Kangaroo Island. The echidnas, Tachyglossidae, are classified in two living genera, the smaller short-beaked echidna (genus Tachyglossus), represented by one species, Tachyglossus aculeatus (Shaw, 1792), and the larger long-beaked echidnas (genus Zaglossus), with three living species currently recognized (

Though Tachyglossus is regarded as the only extant echidna in Australia, until the late Pleistocene several additional tachyglossids, all larger than Tachyglossus, occurred in Australia. Megalibgwilia owenii (Krefft, 1868) (often called Megalibgwilia ramsayi, a junior synonym, in current literature) was a Zaglossus-sized echidna (estimated mass circa 10 kg, but more robust than Zaglossus and with a less elongate or downcurved rostrum) known from Pleistocene localities in New South Wales (Wellington Caves), South Australia (Naracoorte), Tasmania (Montagu Caves and King Island), and south-western Western Australia (Tight Entrance Cave) (

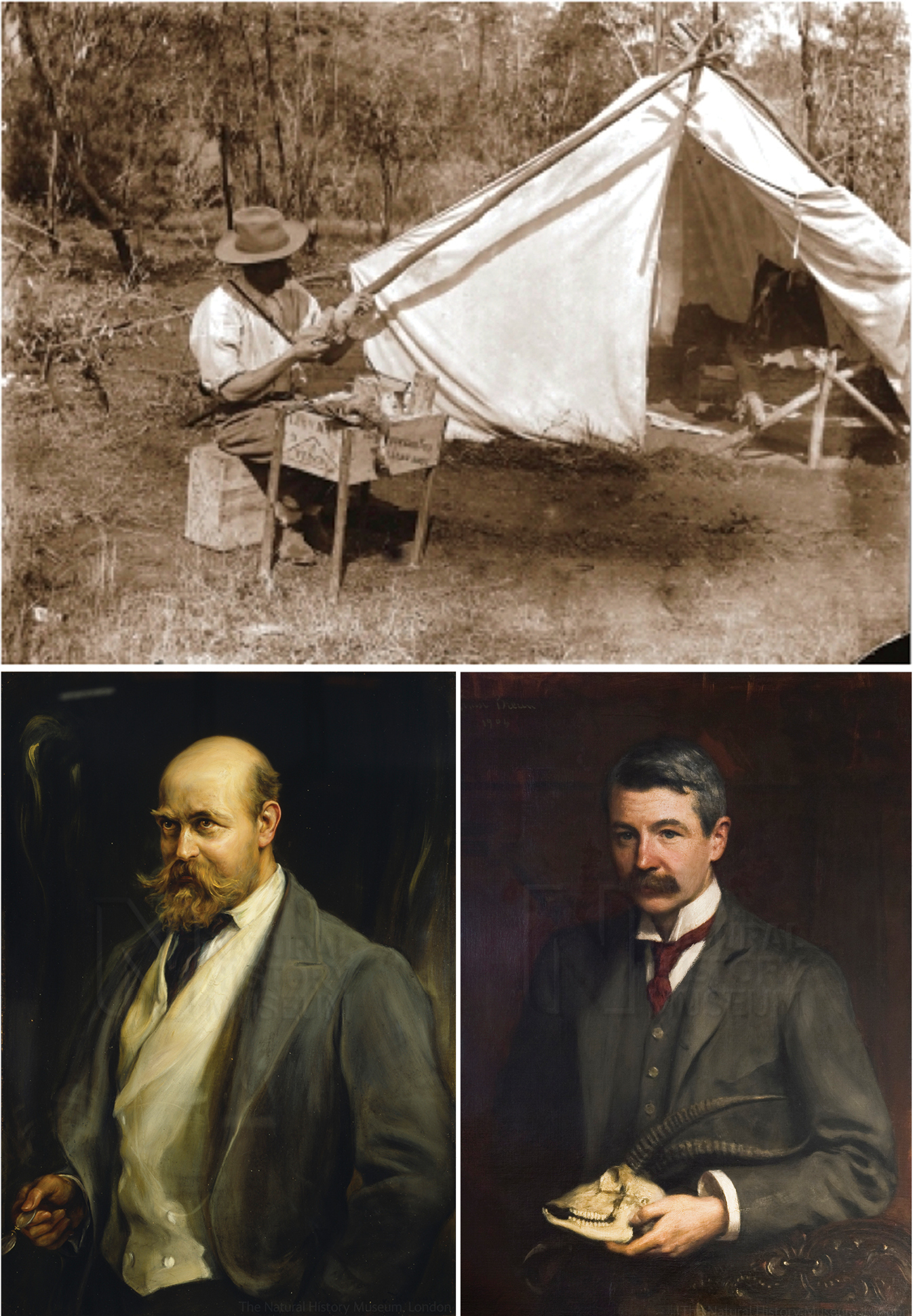

Here we report an overlooked modern museum specimen (skin, skull, and forelimb skeleton) of Zaglossus that was apparently collected in 1901 in the West Kimberley region of north-western Australia by the Australian naturalist and collector John T. Tunney (Figure 3). Based on an agreement between Lord L. Walter Rothschild, the eccentric naturalist who built up an astonishingly large personal collection of natural history specimens in his private museum in Tring (in the county Hertfordshire outside of London), and Bernard Henry Woodward, the London-born director of the Western Australian Museum in Perth, Tunney was commissioned by Rothschild to travel through some of the most remote areas of northern Australia in the first years of the twentieth century in order to collect butterflies, moths, mammals, and birds for Tring, and Aboriginal cultural artifacts for the museum at Perth. From April 1901 to November 1903, in a pioneering effort, Tunney collected natural history specimens and cultural artifacts along a transect that extended from the Pilbara Region in Western Australia to the South Alligator River in Northern Territory, before returning to Perth (

Despite the importance of Tunney’s mammalogical collections, no full report on these materials has ever been published. The most important account is M.R. Oldfield Thomas’ (

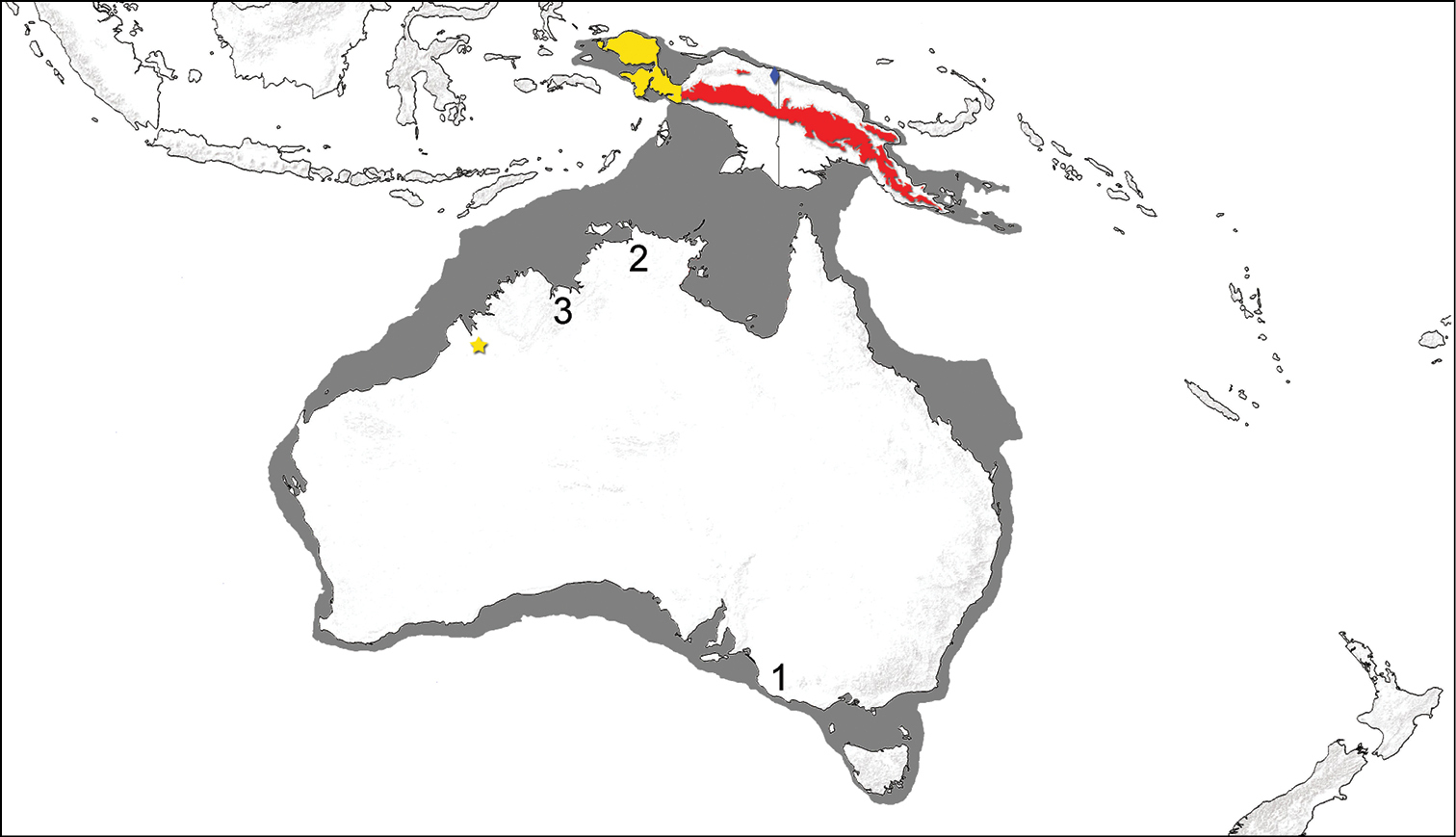

Map of the Greater Australian continent. Map includes an outline of the larger land mass know as “Sahul” or “Meganesia” that forms when the continental shelf (dark grey) is exposed during glaciation. Overlaid is the modern distribution of the three recognized species of Zaglossus: Zaglossus bartoni (red), Zaglossus bruijnii (yellow), and Zaglossus attenboroughi (blue diamond), with the Kimberley record of Zaglossus bruijnii highlighted by a yellow star. Other possible Australian records of Zaglossus cf. bruijnii are numbered by general locality: 1 Pleistocene fossil remains from Naracoorte, South Australia, referred to Zaglossus cf. bruijnii by

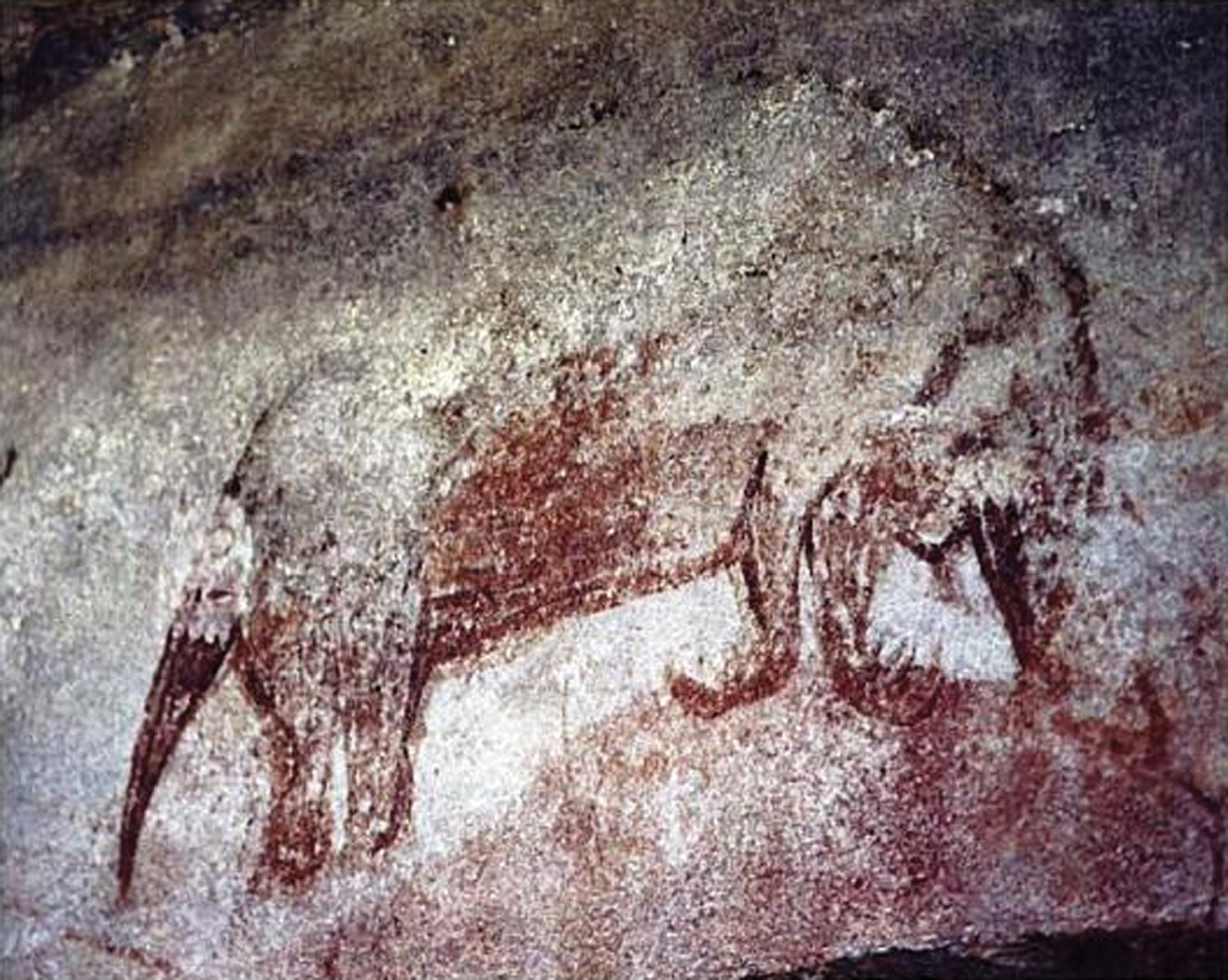

Australian rock art of Zaglossus. Photograph of an Aboriginal rock art illustration from Arnhem Land depicting the characteristic long and down-curved beak (and whitish head of some specimens) of Zaglossus (see

Dramatis personae. Clockwise from top: Australian natural history collector John T. Tunney (1871–1929), preparing specimens on the northern Australian expeditionary efforts during which his Zaglossus specimen was collected; M.R. (Michael Rogers) Oldfield Thomas (1858–1929), mammal taxonomist at the British Museum (Natural History), London, who studied the Tunney Zaglossus specimen; Lord L. (Lionel) Walter Rothschild (1868–1937), eccentric collector and naturalist who used his family fortune to amass a very large personal scientific collection, which became the Zoological Museum at Tring and included the Tunney Zaglossus specimen. Tunney portrait courtesy of the Western Australian Museum, Perth; Rothschild and Thomas portraits courtesy of the Natural History Museum, London.

Specimens discussed in this paper are stored in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History, New York , USA (AMNH); the Natural History Museum, London, UK (BMNH); the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA (MCZ); the Museum Zoologicum Bogor, Cibinong, Indonesia (MZB); the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA (USNM); and the Western Australian Museum, Perth, Australia (WAM).

During a visit to the Natural History Museum, London, in 2009, the first author studied a museum skin of Zaglossus bruijnii (BMNH 1939.3315; Figures 4–9), bearing original tags from John T. Tunney, stored among supposedly unprovenanced specimens of Zaglossus. This skin also has an associated cranium, mandibles, and distal right forelimb elements, which were extracted from the study skin early in the twentieth century (see below). The tags record the collection of this specimen from Mount Anderson, an inland locality in the West Kimberley region of north-western Western Australia, on 20 November 1901 (Figure 7).

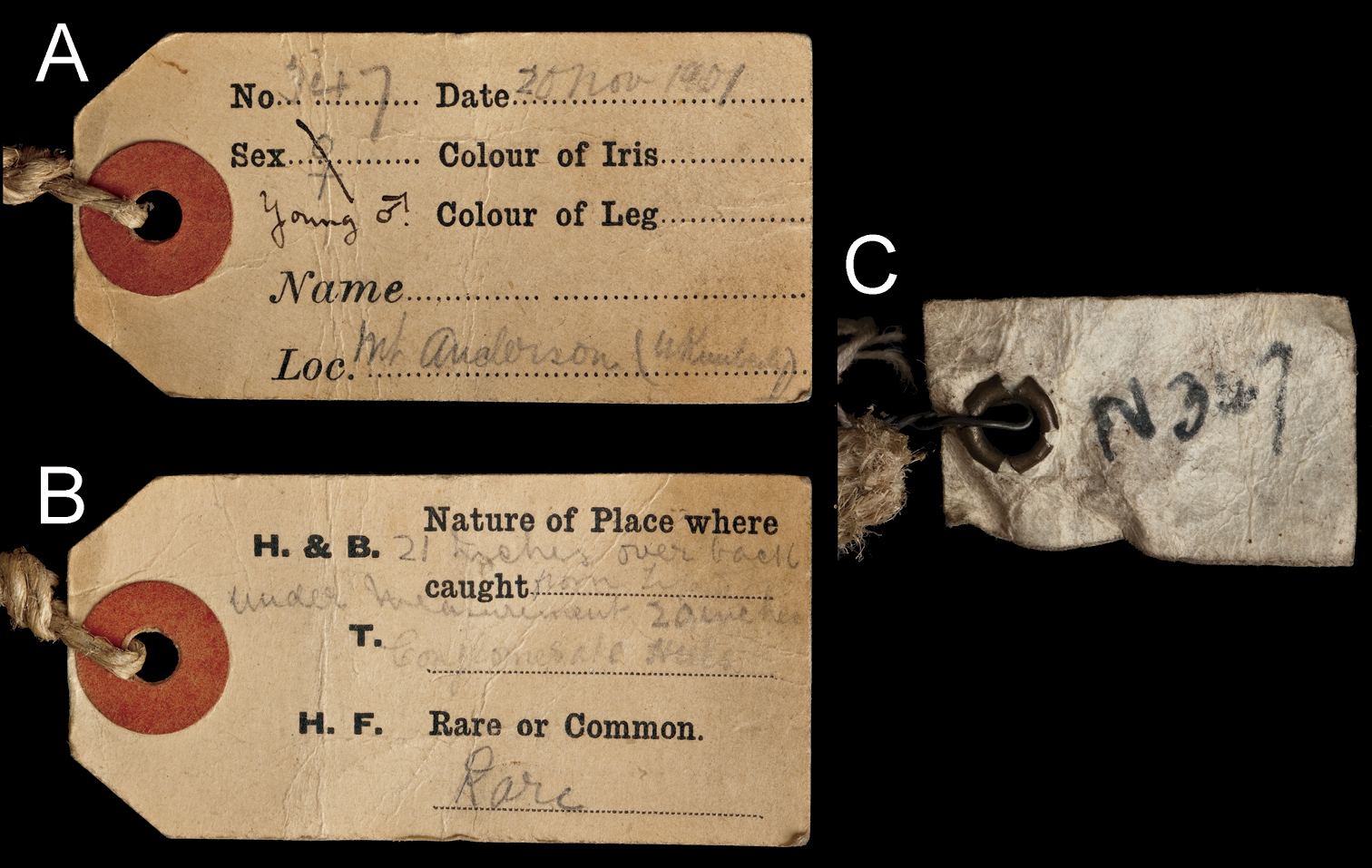

Tunney’s typical tags (used by Tunney and some other collectors from the Western Australian Museum in Perth) were strong card tags preprinted with the following categories (see figure in

Tunney’s tag, written in his characteristic handwriting, and tied with thick sturdy string to the right hindfoot of the specimen (Figures 4 and 7), bears an original field number (347), a date (“20 Nov. 1901”), reports the specimen’s collection from “conglomerate hills” (“Nature of Place where caught”) at “Mt Anderson (W Kimberley)” (locality), and indicates that it was “Rare” (a classification only occasionally reported on his mammal tags). Tunney originally marked the sex of the animal as female (“♀”), which was later corrected in pen on the tag to “young ♂” (reflecting a mammal difficult to sex, as echidnas can be). Tunney left the “Name” field blank on his tag, which is somewhat unusual—he usually reported a scientific or common name on his mammal tags. This may indicate that Tunney was uncertain exactly what species he had before him. Tunney also usually reported standard length measurements on tags for his mammal and bird specimens (i.e., head-body, tail, and hind foot lengths), but in this case he gave the measurements of the specimen only as “21 inches over back from tip to tip” and “under measurement 20 inches”, indicating a mammal for which the head-body and tail lengths were unusually difficult to measure. Thetotal study skin, as now prepared, still measures about 21 inches measured over the dorsum and 20 inches measured along the underside. The specimen also bears a smaller field tag, worn and dirty, that is made of cloth-like paper, attached to the right hindleg with wire, and bearing only the field number, “N 347” (Figure 7).

The specimen is a well-made study skin, with the hindlegs directed posteriorly and the forelegs folded back against the underside (Figure 4). It was originally prepared with the skull and parts of the limbs retained intact inside the skin (the skull and right forelimb were apparently later removed from the skin and prepared in England—see below). The pelage is quite pale brown, and the specimen is rather sparsely furred, with mostly white spines, and has spines invading the sides of the belly, claws only on the middle three digits of both forefeet and both hindfeet, and hindleg spurs.

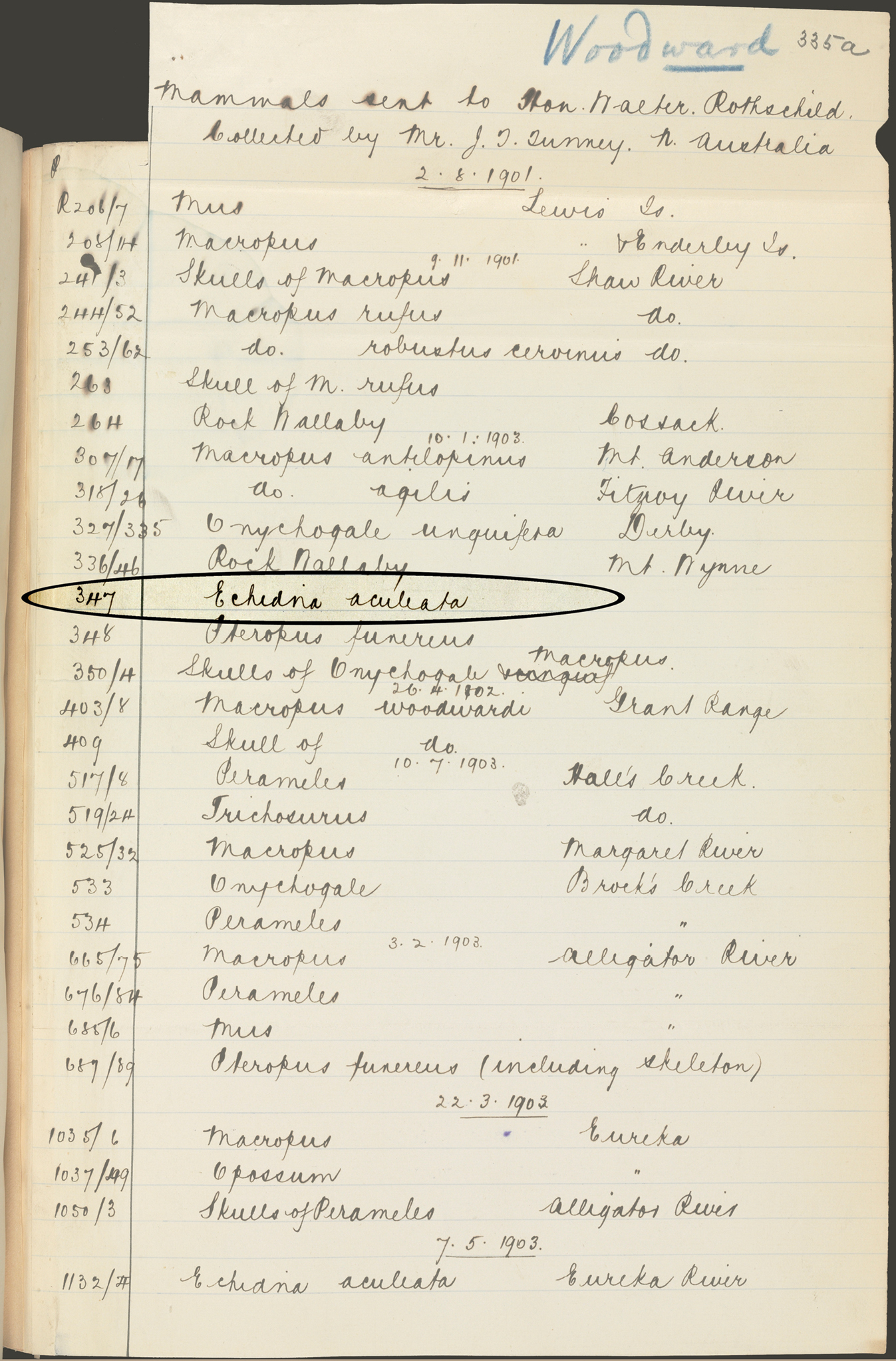

This specimen was misidentified as a Short-beaked echidna before its skull was extracted and studied. Identified by field number (347), it was listed as “Echidna aculeata” (i.e., Tachyglossus aculeatus) when it was sent from Australia to Rothschild at Tring, and identified as such in a letter dated 25 April 1904 sent by Bernard Woodward to Oldfield Thomas in London, discussing details of the mammal specimens collected by Tunney (Figure 8). Soon after its arrival at Tring, ectoparasite specimens taken from this skin formed the basis for the description of a new species of tick, Amblyomma australiense, by

Though the identification of this specimen as Zaglossus has gone unreported in the literature until now, we are not the first researchers to notice that this specimen provides a modern record for Zaglossus from Western Australia. Oldfield Thomas, arguably the greatest mammalogical taxonomist of all time, examined Tunney’s specimens when they arrived in England, and made notes that indicate he understood Tunney’s specimen was a Kimberley Zaglossus. Thomas would have known that the Tunney skin in question was a Zaglossus rather than a Tachyglossus the moment he saw it, even if Rothschild was unaware of this. Thomas apparently removed the skull (the skull, by its lack of sutural ossifications, shows the animal to be a nearly mature subadult) and the bones of the right forelimb (articulated radius, ulna, and forefoot) from the study skin. The skull is intact apart from some missing basicranial fragments and is labelled “Kimberley” in Thomas’ handwriting on the palate (Figure 5); it also bears two labels in Thomas’ handwriting, one identifying the specimen as an “imm[ature]. Zaglossus, coll[ected by]. Tunney” and the other noting that the skull compares favorably to an immature specimen of Zaglossus bruijnii from Fakfak (western New Guinea) preserved in the Zoological Museum in Amsterdam. The dentary is also marked in ink with the word “Kimberley” in Thomas’ handwriting (Figure 5). Thomas labeled the forelimb “Zaglossus Kimberley N.W.A. (Tunney)” (i.e., N.W.A. = north-western Australia) (Figure 6). These labels indicate to us that Thomas recognized that the specimen was indeed a Zaglossus, and that he was satisfied that it had been collected by Tunney in the Kimberley region of Australia. We suspect that Thomas extracted the right forelimb elements from the skin of the specimen to see if its humerus was preserved. He would have wanted to compare it to the humeri of the large fossil echidnas that had previously been described from Australia; the holotypes of two large echidna taxa described from the Australian Pleistocene (Echidna owenii Krefft, 1868, Echidna ramsayi Owen, 1884, now classified in the genus Megalibgwilia) are right humeri (

It is not clear on what date Thomas extracted the skull and forelimb of the Tunney specimen, but he may have written the accompanying labels after 1907 (or replaced them with newer labels if he had written them earlier), because until at least 1907 Thomas was apparently under the impression that Acanthoglossus (rather than Zaglossus) was the correct generic name for the long-beaked echidnas (

While Thomas’ impressions as to the identity of the Tunney Zaglossus specimen seem clear, it is not clear whether Rothschild was aware that the specimen was a Zaglossus, or if so, whether he accepted its authenticity. Rothschild published several observations on echidna taxonomy (

From the beginning of our investigations regarding this specimen, we have of course considered whether its original Tunney field tags truly belong to it, or whether they might have been transferred to it by mistake, as the latest tag associated with the specimen implies. However, several lines of evidence point to the fact that Tunney’s tags were always associated with an echidna, and that this tag was not likely to have been transferred by mistake from a Tachyglossus specimen to a Zaglossus specimen.

In addition to Tunney’s original tag, two sources—correspondence between Perth and London/Tring, and several parasitological publications—establish that Tunney’s specimen (his field number 347) was definitely an echidna, such that we are certain that its original tags were not transferred by mistake from a specimen of some other kind of animal. The specimen was mentioned in the original export paperwork, and discussed in parasitological literature, as Tachyglossus aculeatus (originally as Echidna aculeata), and its tag data, including the difficulty of sexing and the style of measurement, suggest an echidna. Thus the only conceivable mix-up could involve a Tachyglossus specimen collected by Tunney, with tags that became disassociated from the original specimen, and later erroneously attached to a specimen of Zaglossus bruijnii that came from New Guinea. However, we believe that Tunney’s original tags from Mt. Anderson are authentically associated with this Zaglossus specimen for several reasons. First, the nature and timing of any putative specimen switch is difficult to understand. Tunney collected only a few Tachyglossus during his expeditions in northern Australia, and these seem to be accounted for in the WAM and BMNH collections, and we note with interest that these tags were written somewhat differently. For example, on the tag of the only Tunney-collected Tachyglossus at BMNH, Tunney provided the name of the species as “Echidna” (left blank on the Zaglossus tag), and stated its abundance as “numerous” (“Rare” in the case of the Zaglossus specimen). Second, such a switch would have to have taken place after the echidna specimen arrived at Tring (in 1903-1904), not earlier in Perth, because no Zaglossus specimen was available in Perth—Tunney never collected in New Guinea, and the WAM has apparently never had a modern Zaglossus specimen in their mammal collection (as judged by details from the WAM accession register). But any switch must have already happened by the time that Thomas first inspected the Tunney specimens sent to Tring, as it seems clear that Thomas accepted that Tunney’s specimen number 347 was a Zaglossus collected in the Kimberley region once he was able to make confirming examinations of its skull and forelimb. Thomas had already published one report on Tunney’s 1903-1904 shipment to Tring by 1904 (

Another important consideration is the size of the animal measured by Tunney. Tunney’s tag gives the specimen’s total length measurement as 21 inches (= 533 mm), and this value matches very well the size of the study skin to which it is currently attached, as measured with a flexible measuring tape. This body size measurement is consistent with either a subadult Zaglossus (i.e., like the specimen to which it is attached) or an unusually large adult Tachyglossus. Total length measurements of 539-1000 mm have been reported for adult Zaglossus bruijnii (

Study skin of the Kimberley Zaglossus (BMNH 1939.3315), bearing the original field tags of John T. Tunney. From top: dorsal, ventral, right lateral, and left lateral views. Scale bar = 5 cm.

Cranium and dentaries of the Kimberley Zaglossus (BMNH 1939.3315). From top: dorsal view of the cranium, dorsal view of the dentaries, ventral view of the cranium, ventral view of the dentaries, and, at bottom, close-up views of Thomas’ labeling of “Kimberley” on the specimen’s palate (left) and dentary (right). Scale bar = 20 cm.

Articulated right forelimb elements of the Kimberley Zaglossus (BMNH 1939.3315). Associated label notes “Zaglossus Kimberley N.W.A. (Tunney)” in Thomas’ handwriting. Ventral view above, dorsal view below. Scale bar = 5 cm.

John Tunney’s original field labels attached to the skin of BMNH 1939.3315. A front of card skin tag (attached with sturdy twine to right ankle of study skin) bearing original data, providing the specimen’s field number, date of collection, age and sex, and locality B back of same card skin tag bearing original data, detailing the specimen’s measurements, context of collection, and abundance C cloth tag bearing original field number (“N 347”), wired tightly to right ankle of study skin. See text for details.

Specimen export list. A list of specimens shipped from Perth to Tring included in a letter, dated 25 April 1904, from Bernard Woodward at the Western Australian Museum to Oldfield Thomas, detailing the transfer of Tunney specimens to Rothschild at Tring. The list includes his number 347 (now BMNH 1939.3315), an echidna identified as “Echidna aculeata” (i.e. Tachyglossus aculeatus) prior to Thomas’ examination of the specimen in London, where he realized it is a Zaglossus; we have circled and highlighted this entry in the list.

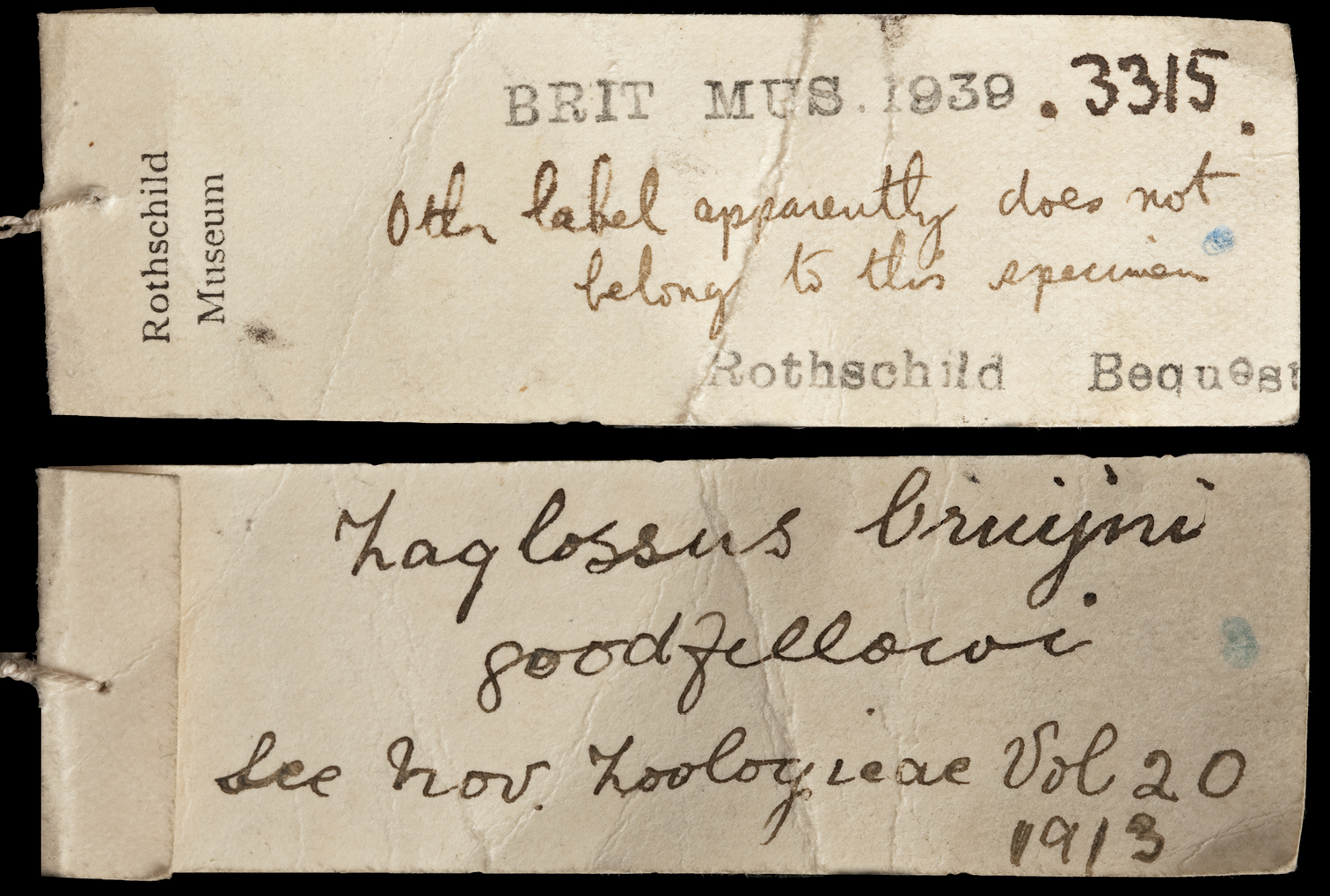

Non-original tag (views of front and back) added at Tring or BMNH, and apparently bearing the handwriting of Tring taxidermist Fred Young. The tag bears a note suggesting that the original labels must be incorrect because the specimen corresponds to Rothschild’s concept of Zaglossus bruijni goodfellowi, then considered endemic to the Indonesian island of Salawati, following his 1913 key (

The tag locality provided by Tunney for the Zaglossus specimen is “Mt. Anderson, W Kimberley.” First named in 1879 by Alexander Forrest in his “North-West Expedition” from DeGrey to Darwin (

Inland areas of the West Kimberley were settled by white Australians for sheep and cattle pastoralism in the aftermath of Forrest’s surveys (since 1881) but the region has historically been very sparsely inhabited by both European and Aboriginal communities (

The distribution of Zaglossus in New Guinea is today centered on montane tropical rainforests (but open areas of subalpine grassland are also prime habitat, and some areas of lowland forest and limestone country are also utilized). It might thus be expected that the last areas of survival for Zaglossus populations in the Kimberley would be in the region’s many tiny and scattered evergreen rainforest fragments, which are largely distributed to the north of the Fitzroy River (

"Environment. The rugged mountain ranges, elevated plateaux, steep hills, and associated valleys have a complex geological pattern with quartzites, sandstones, shales, slates, schists, basalt, dolerite, and limestone. It is mostly rough, inaccessible, unproductive, and undeveloped. Soils are varied but characteristically skeletal with extensive outcrop.

Composition. Most of the lands are within the higher-rainfall area and the vegetation of these parts is an open woodland with moderate shrub layer and grassy ground storey of curly spinifex pasture type…. In the lower-rainfall parts the vegetation is more stunted and open and the grass layer is hard spinifex… Grasses other than spinifex are poorly represented. Edible top feed is also scanty.

Pastoral Value. Only where these lands are adjacent to better country is utilization possible. They are more likely to have a nuisance value. They are generally well watered and therefore provide a hideout for scrub bulls, increasing the difficulty of herd management and mustering. At best it will remain extremely poor pastoral country.

Reaction to Grazing, and Management. Much of the area is unstocked and there is little or no evidence of pasture degradation or denudation except in isolated, restricted areas adjacent to watering points."

A visual representation of the vegetation currently present around Mount Anderson today can be seen with mapping resources available in the online resource Atlas of Living Australia (http://spatial.ala.org.au/), which indicates that present vegetation is dominated by “Acacia open woodlands” but also includes some small areas of “Rainforest and vine thickets.” We suggest that these latter habitats (rainforest, vine thickets) would be relevant remnant habitat for Zaglossus, and that these habitats were likely more expansive at the time of Tunney’s visit to the region well over a century ago in 1901.

Relatively inaccessible and sparsely inhabited rocky areas provide some of the most important remaining areas of occurrence for Zaglossus in New Guinea, on the southern and northern slopes of the Central Cordillera, and in limestone country throughout the “Bird’s Neck” region in the west of the island. That similarly remote and sparsely inhabited areas of northern Australia apparently sheltered at least one remnant population of Zaglossus into the twentieth century is an astonishing realization, and serves as strong encouragement for wildlife researchers to undertake surveys of remote candidate areas of northern Australia with the goal of establishing whether Zaglossus may still exist in any rainforest fragments or rugged gorges across the Kimberley.

We confidently identify the Kimberley specimen of Zaglossus as the Western Long-Beaked Echidna, Zaglossus bruijnii, otherwise known only from the western portion of the island of New Guinea, which it matches in size, cranial features, claw number, and pelage features. Zaglossus bruijnii is the only echidna taxon that typically lacks claws on the first and fifth digits of all feet (the claw conformation seen in the Kimberleyspecimen), and always lacks a claw on the first digit of the hindfeet (a claw is always present on the first digit of the hindfoot in Zaglossus bartoni) (

The Western Long-beaked echidna, Zaglossus bruijnii, occurs in western New Guinea in habitats from as low as sea level up to the top of the highest peaks in the Vogelkop Peninsula—in the Tamrau and Arfak Ranges (to 2900 m)—and from the land-bridge island of Salawati in the west, to the “Bird’s Neck region” of New Guinea in the east, extending as far east as the Fakfak Range and possibly the Charles Louis Ranges on the western edge of the Central Cordillera (in the south) and possibly to the eastern shores of Geelvink (= Cenderawasih) Bay (in the north) (Rothschild in

Though previously recorded only from western New Guinea, Zaglossus bruijnii is the Zaglossus taxon occurring in closest geographical proximity to the Kimberley region, and is the only Zaglossus regularly documented in lowland contexts. Given that similar relevant habitats, including sparsely inhabitated limestone country and remnant rainforests, are to be found across the Kimberley region, it does not surprise us that the modern Kimberley representative of the genusshould be Zaglossus bruijnii. We envision a late Pleistocene distribution of Zaglossus bruijnii that extended across rugged, rocky country and rainforests along the western parts of the Sahul Shelf, comprising much of the area between Australia and New Guinea that has been inundated by the Arafura Sea since the terminal Pleistocene, thus connecting the restricted Recent range from the Vogelkop Peninsula in the north to the Kimberley region and Arnhem Land in the south.

The Kimberley Zaglossus specimen, while overlooked in mammalogical literature, has been referenced with surprising regularity in parasitological papers. It is the “symbiotype” (i.e., host to the type series;

The flea Echidnophaga liopus is so far documented firmly only from Tunney’s Zaglossus specimen and is unknown to date in Tachyglossus. Other Echidnophaga specimens attributed to Echidnophaga liopus in literature, which come from Indian rodents (Rothschild and Jordan 1906), seem more likely to represent a distinct Asian species (

So far, none of the ectoparasites recorded from Tunney’s Zaglossus have been reported from New Guinea Zaglossus, but very little is known about the parasites of Long-beaked echidnas. We are aware of only two ectoparasites definitively recorded from New Guinea Zaglossus. The tick Bothriocroton oudemansi (Neumann, 1910) has been reported from Zaglossus bruijnii at Fakfak, and from Zaglossus bartoni in the Central Cordillera (

The Late Quaternary occurrence of Long-beaked echidnasin northern Australia is widely accepted on the basis of a compelling Aboriginal rock art illustration (Figure 2), from an undisclosed Arnhem Land locality, that accurately depicts Zaglossus (

It is possible that Aboriginal Australians also interacted with Zaglossus much more recently. In 2001, years before we became aware of the Australian provenance of the Zaglossus specimen reported here, one of us (Kohen) recorded a potential example of living memory of Zaglossus while engaged in field work in the East Kimberley. His account of the experience is as follows:

While conducting faunalsurveys at Faraway Bay, I was accompanied by an Aboriginal woman in her fifties who belonged to the Miriwoong Gadjerong tribe. Their territory extends from the coast inland in the region close to the Western Australia-Northern Territory border. In this part of Australia, tribal affiliation is passed down through the female line. However, Faraway Bay is on her father’s country, and he belonged to the Kwini tribe.

While walking close to the coast, we found a scat. On asking my informant what she thought it was, she correctly identified it as an echidna scat, which she referred to as “porcupine”. As only one echidna is traditionally known from Australia, I assumed that it belonged to Tachyglossus. A few hours later we had returned to the camp and were sharing tea when she commented about the echidna scat we had found. She said that her grandmothers “used to hunt the other one”. I asked her what other one, and she said that she meant a much larger echidna. She indicated its height which I estimated to be around 40 cm.

I was intrigued, as both of her grandmothers were still alive and in their nineties. However, one had recently suffered a stroke and the other lived some distance away. When we returned to Kununurra, I had an opportunity to speak to my informant’s mother. As it happened, I had a copy of Tim Flannery’s 1990 paper [

We readily acknowledge that these kinds of informant accounts are fraught with difficulty of interpretation. However, we mention these interactions, because, like the Tunney specimen, this information from Kohen’s informants could be relevant to the survival of Zaglossus in the Kimberley region into the twentieth century. We suggest that future efforts to investigate the recent survival of Zaglossus in remote northern Australia take into account evidence that may be derived from cultural sources such as rock art, living memories from Aboriginal cultures, and examination of vocabularies relevant to animal names in Aboriginal languages.

We are sufficiently convinced by the tags and information associated with the Tunney Zaglossus specimen to regard it as evidence for the survival of the long-beaked echidna in the Kimberley region into the early twentieth century. We accordingly recommend that the Western Long-beaked echidna, Zaglossus bruijnii, be included in future faunal compilations of the modern mammal fauna of Australia (e.g.,

We realize that, despite our conclusions, summarized here, others may remain skeptical of this Zaglossus specimen’s association with Tunney’s tags. Additional studies of this remarkable specimen might include analyses of ancient DNA, stable isotopes, and trace elements to test its origins and the context of its collection. Further targeted studies of relevant Kimberley Pleistocene and Holocene subfossil assemblages (e.g.

Most of Australia’s remarkable Pleistocene megafauna (gigantic marsupials, reptiles, and birds) became extinct after about 50, 000 years before the present (

Anotherrather unexpected recent addition to the list of Quaternary extinctions in the Kimberley region is a fruit-bat of the genus Styloctenium, identified by

Both Styloctenium and Zaglossus are largely rainforest-associated lineages that today are known only from tropical islands north of Australia. Their presence in the late Quaternary fauna of the Kimberley region doubtless reflects the former presence of extensive mesic forested habitats across much of northern Australia, with fragmentation and extinction of forest-reliant species driven by a combination of climate-change and prehistoric human impacts in recent millennia (

We hold out a small optimism that Long-beaked echidnasmight yet dig burrows and hunt invertebrates in at least one hidden corner of Australia’s north-west. Such hopes are founded on the remoteness of this little-studied expanse of the Australian continent, and on the relatively late discovery of other medium-sized Kimberley mammals including the Monjon, Petrogale burbidgei (

All living Zaglossus taxa in New Guinea are considered to be critically endangered (

Little is definitively recorded about diet in Long-beaked echidnas. Most information is based on anecdotes or extremely limited studies of Zaglossus bartoni, which is thought to be a specialist earthworm feeder that also feeds on subterranean arthropods including centipedes and large insect larvae (

This specimen was kept alive for about a month and a few observations on its habits were made. It was absolutely nocturnal and spent the day partially buried in the deep layer of sand which was kept in its cage… At night it moved about sluggishly, often digging with motions that strongly recalled those of a turtle. It fed on ants only, which were procured by placing in a dish a considerable amount of shredded cocoanut. The ants soon swarmed in this and the whole was then placed in the Proechidna’s cage. It ate the insects by thrusting its long tongue down into the cocoanut. It took a little water or water with condensed milk, but seemed to drink very little.

It may of course be the case that this animal only ate ants because other, more favored foods were not offered to it.

We thank P. Jenkins, L. Tomsett, J. Maclaine, R. How, E. Westwig, P. Sweet, D. Lunde, L. Gordon, S. Ingleby, J. Chupasko, Maharadatunkamsi, and M. Sinaga for assistance with specimens in museum collections around the world. We thank K. Aplin, G. Perri, M. Opiang, T. Flannery, M. Eldridge, C. Groves, M. Copley, E. Ward, R. How, J. Hatton, R. Roberts, R. Robbins, P. Engelbrektsson and O. Crimmen for helpful discussion. We acknowledge the very helpful assistance of M. Triffitt of the Western Australian Museum Library. We thank the Smithsonian Institution, the Natural History Museum (London), and the Australian Biological Resources Study for funding support.