(C) 2013 Előd Kondorosy. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Kondorosy E (2013) Taxonomic changes in some predominantly Palaearctic distributed genera of Drymini (Heteroptera, Rhyparochromidae). In: Popov A, Grozeva S, Simov N, Tasheva E (Eds) Advances in Hemipterology. ZooKeys 319: 211–221. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.319.4465

The history of the taxonomic research of Rhyparochromidae and especially Drymini is briefly reviewed. Two new species level synonyms are proposed: Taphropeltus javanus Bergroth, 1916, syn. n. = Taphropeltus australis Bergroth, 1916, syn. n. = Brentiscerus putoni (Buchanan White, 1878). A monotypic new genus, Malipatilius gen. n. (type species: Scolopostethus forticornis Gross, 1965 from Australia) is established.

Rhyparochromidae, Drymini, new synonyms, new genus, Palaearctic Region, Oriental Region, Australia

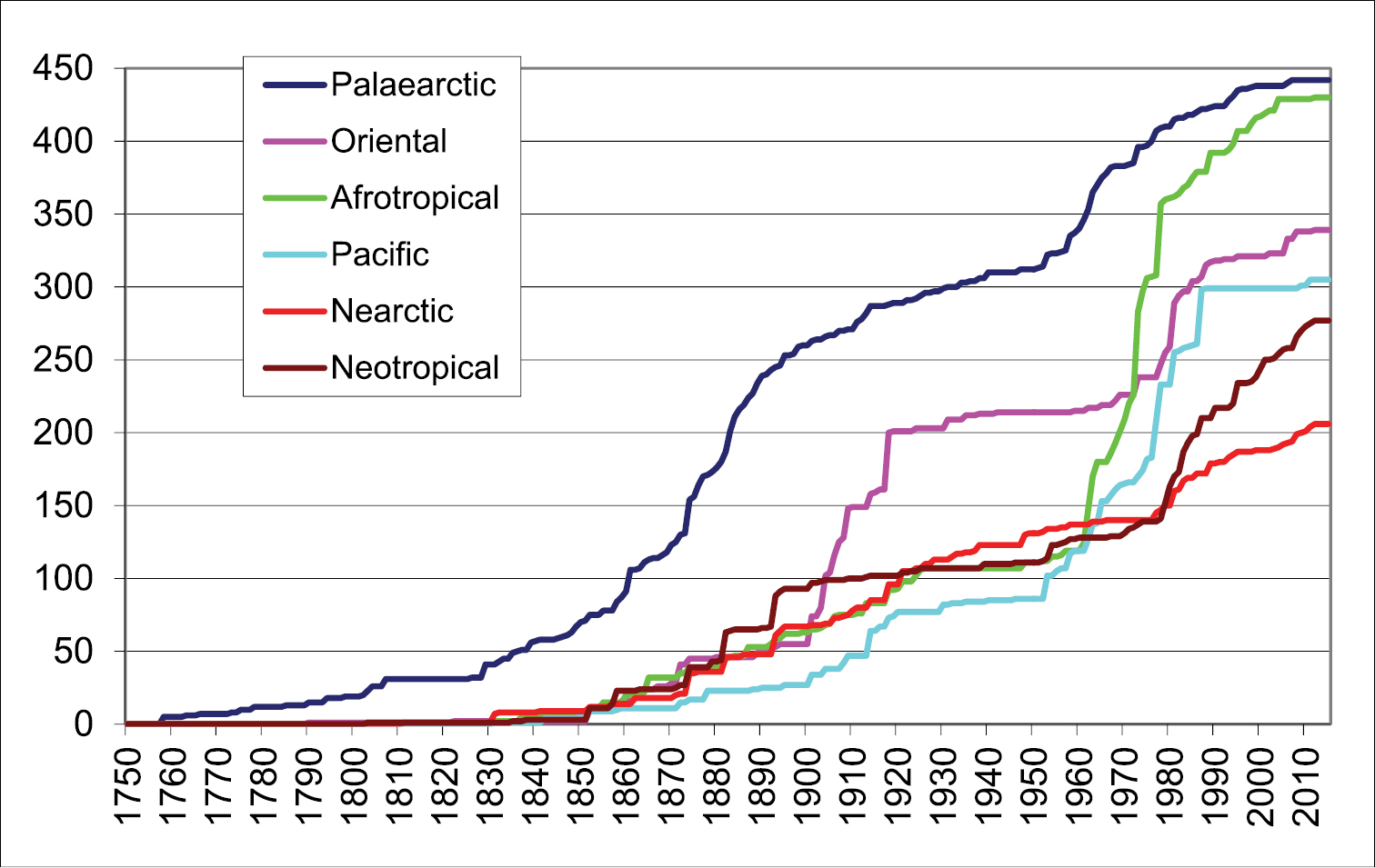

The knowledge on the taxonomy of the true bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) and among them the family Rhyparochromidae developed unevenly during the past more than 250 years (Fig. 1). From Linnaeus till the end of the 19th century the European fauna was most intensively studied. The fauna of the temperate and tropical Americas started to receive more attention from the second half of the century; among others, the work of C. Stål, W. L. Distant and P. R. Uhler is outstanding. The first twenty years of the 20th century was the Golden Age of the research on the Oriental fauna thanks primarily to E. Bergroth, G. Breddin and W. L. Distant). Between the first and second World Wars the research intensity decreased globally except of the Nearctic region where important works were published by H. G. Barber and others. In the 1960’s–1980’s the research underwent an active period, and a high number of new taxa was described especially from the Afrotropical and Australian (+ Pacific) Regions, but also from other regions; the activity of J. A. Slater and G. G. E. Scudder, furthermore A. C. Eyles, R. E. Linnavuori, M. Malipatil and T. E. Woodward was especially significant. In the last twenty years the descriptive activity slackened again.

Number of described valid species of the family Rhyparochromidae from the main zoogeographical regions.

The species occurring in more than one zoogeographical regions are included only once in Fig. 1: in the region of the type locality. Therefore the known species number in each region is more or less higher than the listed one (Palaearctic: 475:442, Oriental: 456:339, Afrotropical: 544:430, Australian: 360:305, Nearctic: 258:206, Neotropical: 393:277). These differences refer to the many common species between certain regions (especially Palaearctic and Oriental or Afrotropical; and Nearctic and Neotropical regions).

The situation in respect of the tribe Drymini is similar to the general trends of Rhyparochromidae. This tribe is of worldwide distribution but in the Western Hemisphere the species richness is much lower (and only one species reaches the Neotropical area in Middle America). A good characterization of the world distribution of the Drymini (and of the other Rhyparochromidae) was given by

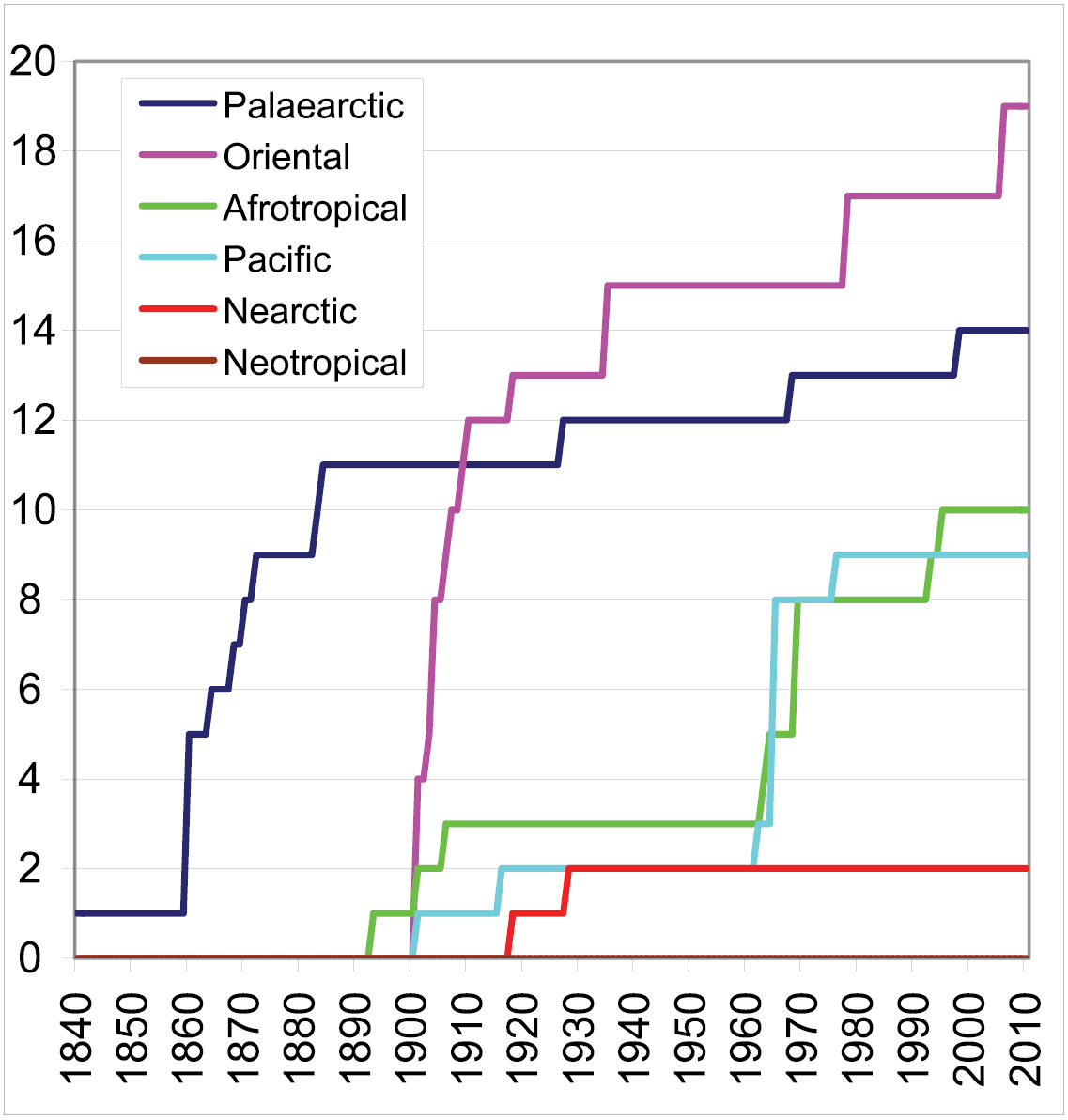

Members of Drymini are usually moderately vagile. This might partly explain the fact that only a few species are distributed in more than one zoogeographical area. Most of these species occur in China where they center the Oriental areas but more or less broadly extend to the neighbouring Palaearctic territories or vice versa. Therefore the species numbers described from the each region are only slightly lower than the actual number of the species known in the respective areas (Palaearctic: 83:87, Oriental: 71:79, Afrotropical: 69:72, Australian: 25:26, Nearctic: 34:36, Neotropical: 1:1).

Examining the history of the genus and species description in Drymini, the following things can be observed (Fig. 2): during the 19th century 12 genera of Drymini were described, 11 of them from the Palaearctic Region. Of the 65 discovered species 51 have Palaearctic distribution. In the first quarter of the 20th century 18 genera and 42 species were described (among them 14 genera and 30 species from southeast Asia). Before World War II the Nearctic species were most intensively studied. The knowledge of the Drymini of the Australian Region was developed extremely thanks to

Number of described valid genera of the tribe Drymini from the main zoogeographical regions.

The species described before the activity of F. X. Fieber were placed in large “general” genera as Lygaeus Fabricius, 1794, Pachymerus Lepeletier & Serville, 1825, or Rhyparochromus Hahn, 1826. Fieber proposed six genera in the Palaearctic Drymini. For the coming few decades the European genera were used to accommodate several new extrapalaearctic species; since most species occurring in the Nearctic Region belong to shared genera it was justified in many cases. Bergroth and Distant were the first to describe several extrapalaearctic genera in the beginning of the 20th century. As a result of their activity, the use of the Palaearctic genera became more restricted. Currently several of these have already been transferred to other genera, but some species have remained “forgotten” or are of uncertain status.

The aim of this paper is to correct some of these incorrect combinations.

Type and non-type specimens of Drymini of the following institutions were examined: Natural History Museum, London (BMNH); Finnish Museum of Natural History, Helsinki (FMNH); Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, Hungary (HNHM); Moravian Museum, Brno, Czech Republic (MMBC); National Museum of Natural History (Naturalis), Leiden, the Nederlands (RMNH); Natural History Museum, Vienna (NHMW); Tirolese Regional Museum (Ferdinandeum), Innsbruck (TLMF); Zoological Museum, Amsterdam (ZMAN), and Natural History Museum, Berlin (MFNB).

As it was pointed out before, most species of Drymini are restricted to a single zoogeographical region. Similarly, most of the genera are also restricted to a single region. As an example, Ischnocoris Fieber, 1860, Notochilus Fieber, 1864, Orsillodes Puton, 1884, and Thaumastopus Fieber, 1870 are of exclusively Palaearctic distribution.

Hidakacoris Tomokuni, 1998 is currently known only from Japan, but there are some undescribed Oriental species which belong to this genus too.

All more widely distributed Palaearctic genera (13) extend to the Oriental region; 7 of them are found only in these two regions. Palaearctic genera containing species extending to Oriental areas are Gastrodes Westwood, 1840, Lamproplax Douglas & Scott, 1868, and Trichodrymus Lindberg, 1927. It is also frequent that an Oriental or pantropical genus has some species inhabiting marginal areas of the Palaearctic Region, most frequently China and Japan. Such genera are Appolonius Distant, 1901, Mizaldus Distant, 1901 (Neomizaldus Scudder, 1968, is probably a junior synonym of the latter), Paradieuches Distant, 1883, Potamiaena Distant, 1910, and Retoka China, 1935.

Drymus Fieber, 1860, is a genus centered in the Holarctic but also having some described and a few undescribed Oriental species.

Taphropeltus is a predominantly Palaearctic genus which currently contains one exotic species, too (two other Palaearctic species are reaching the northern part of the Afrotropical region). The Australian Taphropeltus australis Bergroth, 1916, was originally included in this genus (

The othertropical Taphropeltus species is Taphropeltus javanus Bergroth, 1916, described from Java, Indonesia (

Both Taphropeltus australis and Taphropeltus javanus show similarity to the Palaearctic members of Taphropeltus, but they are readily distinguished from the true Taphropeltus species among others by having a more strongly developed pronotal collar and three rows of claval punctures. Based on the original descriptions only,

Both species were described in 1916. Both of the two journal issues contain explicit information about the date of the publication: the description of Taphropeltus javanus is dated to 12 September 1916, while the article describing Taphropeltus australis was published during October of the same year.

Furthermore, I compared the lectotype and additional non-type specimens of Brentiscerus putoni (Buchanan White, 1878), which is described from New Zealand, with the mentioned species. They are virtually identical. As a conclusion, the following nomenclatural changes are required:

http://species-id.net/wiki/Brentiscerus_putoni

Scolopostethus putoni. Lectotype (designated by

The types of Taphropeltus australis and Taphropeltus javanus are probably lost, no references mentioning them could be traced and they could not be found in FMNH where most of Bergroth’s collection is deposited. Taxonomic decisions were made based by examination of non-type specimens from Australia, New Guinea and Indonesia, respectively.

INDONESIA. Dammerman / O. Soemba / 700 m 249 / Kananggar / v. 1925 (1 male, RMNH); Dammerman / Idjen 1850 m / Ongop-ongop / 19. V. 1924 / No. 17 (RMNH); Banjoewangi / JAVA 1909 / MacGillavry (1 female, HNHM); INDONESIA: centr. Java / Pokalongan Reg., Bandar / 1050 m / 2.1998., leg. S. Jakl (1 female, NHMW); IDN-Bali Isl. / Bedugul reg. 1300m / Tamblingan lak.N.R. / S. Jakl lg., 3.2005 (1 female, MMBC); Sunda Exp. Rensch / W.-Flores / Rana Mêsé / 20.–30.6.1927 (1 male, MFNB); Sumba (E) / Luku-Melolo N. R. / 550 m, VII. 2005 / leg. S. Jakl (2 ex., NHMW). PAPUA NEW GUINEA. New Guinea / Mt. Kaindi / 2400 m / 15-16. IV. 1965 // Nr. 34 / Coll. Balogh et / Szent-Ivány (1 female, HNHM); Austr. New Guinea / Wau 1250 m / 10.-20. XI. 1972 / J. v. d. Vecht (1 male, ZMAN); Museum Leiden / Neth. New Guinea Exp. / Star Range 1260 m / Sibil / 15. VI. 1959 // Taphropeltus 3 (handwriting) (1 female, RMNH); AUSTRALIA. N.S.W. / Cassilis “Kuloo” / Station 710 m / 31°50'9"S, 150°8'E // 25.X.2000 / Hung. Entom. Exped. / leg. A. Podlussány, G. Hangay & I. Rozner (1 male, HNHM); N.S.W. / Karai State Forest / Kookaburra, 943 m / 31°1'4"S, 152°20'2"E // 27–28.X.2000 / Hung. Entom. Exped. / leg. A. Podlussány, G. Hangay & I. Rozner (1 female, HNHM); N.S.W., Putty / Road, Cases Courvert / 10–11.I.2006 leg. G. Hangay, I. Rozner & A. Podlussány (1 male, 2 female, HNHM); N.S.W. / Milton, 21.I.2006 / leg. A. Podlussány, G. Hangay & I. Rozner (1 female, HNHM); New South Wales / J.P. Duffels // Eucalyptus / forest // 48 km N of Singleton / 15 I 1983 (1 female, ZMAN). NEW ZEALAND. C. Darwin / 85–119. (1 male, BMNH); (handwriting): Kaitaia NZ / 1 VIII 23 / JG Myers // Base of prairie grass // (printed): J. G. Myers Coll. B.M. 1937-789. (1 male, BMNH).

The population of Brentiscerus putoni in New Zealand possibly originates from Australia, where all congeners are native. There are no autochthonous Drymini species in New Zealand, only some introduced species occur, as Brentiscerus putoni, Grossander major (Gross, 1965) and Paradrymus exilirostris Bergroth, 1916 (

The other species of the genus Taphropeltus species which are partly of extrapalaearctic distribution are Taphropeltus nervosus (Fieber, 1861) and Taphropeltus ornatus Linnavuori, 1978. Both of these species are morphologically rather distinct from the type species, Taphropeltus hamulatus Thomson, 1870, and the other known Palaearctic members of the genus. It is sure that at least Taphropeltus ornatus belongs to another genus, as it also was suggested by

Although the West Palaearctic species of this complex are easy to classify into one of the two genera, Eremocoris and Scolopostethus are morphologically very close to each other. Some of the described species and also certain undescribed species from the Afrotropical and Oriental Regions are morphologically transitional between Eremocoris and Scolopostethus. E.g., the African Scolopostethus maumus Scudder, 1962, is apparently very closely related to Eremocoris africanus Slater, 1964. The possible synonymy of them was already suggested by

Species currently placed to Scolopostethus live in all major zoogeographic regions, with many undescribed Oriental species. The Australian Scolopostethus forticornis Gross, 1965, belongs to a different, so far undescribed genus which is described below as new. Each of the African Scolopostethus daulias Linnavuori, 1978 and Scolopostethus kilimandjariensis Scudder, 1962 represent another undescribed genus. Scolopostethus daulias seems to be related with Taphropeltus ornatus Linnavuori, 1978, but their relationship needs further investigation. Scolopostethus kilimandjariensis belongs to a new genus but its description must be done in frames of a comprehensive study on all other Afrotropical members of the Scolopostethus–Eremocoris complex.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:1B42F8DE-6D15-4B14-BE9B-BD02DEAF79FC

Scolopostethus forticornis Gross, 1965, by present designation.

Body elongate oval, dull, extensively punctate, dorsally glabrous (Fig. 3).

Head pentagonal, with dense fine punctures. Eyes small, very prominent. Ocelli well developed, located very far from each other, near the eyes. Antenniferous tubercle curved laterally. Antenna very robust, subclavate.

Pronotum without anterior collar, transversal furrow deep, disk densely punctured. Anterior and posterior margins straight, lateral margin concave, explanate but not widened at transversal furrow. Anterior lobe more globose in male, lateral margin partially parallel here. Scutellum elevated at middle. Fore wing. Clavus with 3 regular rows of punctures. Corium evenly and densely punctate, nearly parallel, costal margin only slightly concave subbasally, apical margin straight. Thoracic sternum punctate except submedian parts of mesosternum. Legs robust, fore femur strongly incrassate, especially in male, with two rows of spines and a very large spine in inner row.

Abdomen with dense decumbent pilosity, lateral portion of intersegmental suture between sternites IV–V curved anteriorly, not reaching lateral margin and sublateral furrow; trichobothrial pattern as typical in Drymini.

Malipatilius forticornis (Gross, 1965), new combination.

The genus is apparently not monotypic, because besides of the type species very probably congeneric specimens were seen at least from Java, Kalimantan and the New Hebrides.

The type species of Malipatilius gen. n. was originally placed into the genus Scolopostethus. The diagnostic characters of the two genera are presented in Table 1. A typical Scolopostethus species, Scolopostethus ornandus Distant, 1904 is imaged for comparison on Fig. 4. Faelicianus Bergroth, 1918, is perhaps the sister genus of Malipatilius gen. n. This genus has a pale wide lateral carina on pronotum, which is broadened at transversal impression, therefore the pronotum is evenly convex laterally. The antenna is also slender, much more than even in Scolopostethus. Another known genera of Drymini, e.g. the superficially similar Salaciola Bergroth, 1893, which sometimes has similar colour and explanate pronotal carina, are certainly not closely related.

Etymology. Patronymic, named after and dedicated to Mallik B. Malipatil, recognizing his excellent contributions to various groups of Australian Heteroptera, particularly Rhyparochromidae. Gender masculine.

Scolopostethus ornandus Distant, 1904.

Diagnostic characters of Malipatilius gen. n. and Scolopostethus.

| Character | Malipatilius gen. n. | Scolopostethus |

| Eye | hind margin straight | rounded |

| Antennal segment I surpassing apex of head | short, less than half length of segment | longer, more than half length of segment |

| Length: width ratio of antennal segment III | ~3.5 | more than 5 |

| Colour of pronotum | unicolorous dark (sometimes posteriorly slightly paler) | tricoloured |

| Lateral margin of pronotum | invariably dark | always pale on middle |

| Pronotal margin at transverse furrow | virtually not widened; strongly concave | distinctly widened, straight or slightly concave |

| Anterior pronotal lobe of male in side-view | strongly emerging, approximately as high as posterior margin | slightly emerging, nearly evenly sloping |

| Transversal furrow | deep | shallow |

| Posterior pronotal margin | straight | concave |

| Scutellum in side-view | convex | flat |

| Number of rows of punctures on clavus | 3 (inner row sometimes incomplete) | 3.5–4 |

| Punctures on corium | even and dense | inner part with smooth parts |

| Apical margin of corium | straight | slightly S-shaped |

I am very thankful to Dávid Rédei for the reviewing of the text. I am indebted to Michael D. Webb (BMNH), Dávid Rédei (HNHM), Petr Baňař (MMBC), Herbert Zettel (NHMW), Jan van Tol (RMNH), Joannes Petrus Duffels (ZMAN) and Jürgen Deckert (MFNB) for the opportunity of studying the type and another specimens.