(C) 2012 Ewa Simon. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Simon E (2012) Preliminary study of wing interference patterns (WIPs) in some species of soft scale (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha, Coccoidea, Coccidae). In: Popov A, Grozeva S, Simov N, Tasheva E (Eds) Advances in Hemipterology. ZooKeys 319: 269–281. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.319.4219

The fore wings of scale insect males possess reduced venation compared with other insects and the homologies of remaining veins are controversial. The hind wings are reduced to hamulohalterae. When adult males are prepared using the standard methods adopted to females and nymphs, i.e. using KOH to clear the specimens, the wings become damaged or deformed, an so these structures are not usually described or illustrated in publications. The present study used dry males belonging to seven species of the family Coccidae to check the presence of stable, structural colour patterns of the wings. The visibility of the wing interference patterns (WIP), discovered in Hymenoptera and Diptera species, is affected by the way the insects display their wings against various backgrounds with different light properties. This frequently occurring taxonomically specific pattern is caused by uneven membrane thickness and hair placement, and also is stabilized and reinforced by microstructures of the wing, such as membrane corrugations and the shape of cells. The semitransparent scale insect’s fore wings possess WIPs and they are taxonomically specific. It is very possible that WIPs will be an additional and helpful trait for the identification of species, which in case of males specimens is quite difficult, because recent coccidology is based almost entirely on the morphology of adult females.

Scale insects, Coccidae, wings, males, WIP, interference colour patterns

The superfamily Coccoidea or scale insects contains 7500 species of plant feeding hempiterans, comprising 48 families (according to

Within this superfamily, there is a very marked dimorphism between the adult male and female, both in their morphology and life histories, such that it is impossible to identify the male and female of the same species (or even family) using the same combination of characters (

Adult females are sack-like, with the head, thorax and abdomen fused together. They are all wingless and many have reduced legs and antennae but the mouth parts are usually well developed. They can be quite long lived, surviving for several months on their host plants. The adult males are delicate, ephemeral insects without mouth parts, and so live as adults for only a few days. They are usually alate, although characterized by diptery, and resemble small delicate flies (

Species of Coccoidea are almost always described based on female structure, whilst most males are so poorly known that they are mostly unidentifiable to species (

As was mentioned above, only male Coccoidea possess wings. These structures have a very simplified venation in the fore wings whilst the hind wings are reduced to hamulohalterae. Because of this simplification and because the wings have been lost from all females, it was considered that the wings were featureless and therefore their morphology has been neglected (

The males are polymorphic with respect to the wings, i.e. winged, brachypterous, and wingless forms have been accepted by natural selection. During further evolution and adaptation to different ecological conditions the polymorphism has been retained or one morph has been preferred. Wing and wingless form may occur in different groups or within the same taxon, sometimes even in the same species (

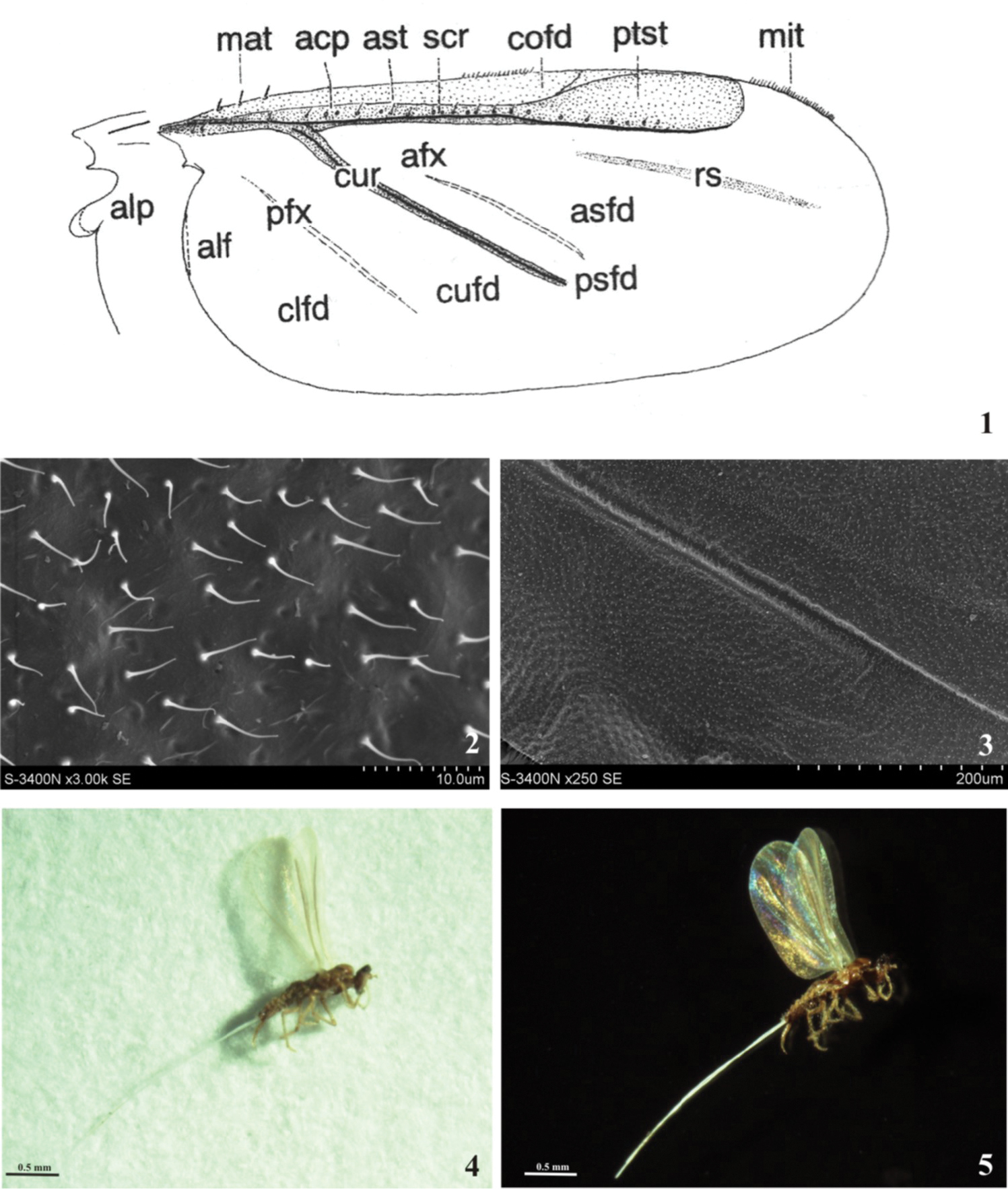

1 General scheme of the fore wing (after

The anterior wings are folded flat and overlap along the abdomen in resting position which facilitates the moving among soil particles, plant parts, etc. Shape of the wing is usually oval, but also with parallel anterior and posterior margins, with distal part wider than proximal one or reversely; with broad or narrow base, with rounded or acute apex.

For reception hamuli serves the narrow anal fold or projecting alar lobe with a pocket. On the wing there are two ridges: subcostal ridge which runs along costal margin from wing base toward wing apex; cubital ridge which originates from the former at about 1/5 wing length and runs obliquely to posterior wing margin. On the membrane of the wing might be present flexing patches (light lines) anterior – between subcostal ridge and cubital ridge and posterior – between cubital ridge and posterior wing margin. A slightly sclerotized oblique patch, which runs posterior to subcostal ridge is called radial sector. The ridges and flexing membranes divide the wing into fields, which are illustrated on Fig. 1. Depending on the development of ridges and flexing patches the fields assume various shapes, size, and may join or disappear. Pterostigma is present in some Archaeococcids and is hypodermal club-shaped thickening in front, or behind, subcostal ridge, not bordered with any veins (

Compared with most other structures, the wings of scale insects are best preserved dried or as fossils and have thus been found to be important in paleontological studies. The wings of recent specimens, prepared using standard methods adopted to females and nymphs (i.e. using KOH solution), become deformed or damaged, and usually are not described or drawn in publications (

WIPs of seven species of the family Coccidae belonging to six genera were studied: Eriopeltis lichtensteini Signoret, Eulecanium tiliae (Linnaeus), Luzulaspis frontalis Green, Luzulaspis nemorosa Koteja, Parthenolecanium corni (Bouche), Pulvinaria vitis (Linnaeus) and Sphaerolecanium prunastri Boyer de Fonscolombe. This material comes from Koteja’s collection of scale insects deposited in Department of Zoology (University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland), and from author’s collection (only puparia with accompanied females were collected) (Table 1).

The collection data of the studied material (KC – Koteja’s collection, AC – author’s collection).

| species | number of specimens studied | collection | date of collection | place of collection | plant | geographical coordinates |

| Eriopeltis lichtensteini Signoret, 1877 | 25 | KC | 28.7.1967 | Makowska Gora near Sucha, Poland | Agrostis vulgaris | |

| 20.09.1968 | - | - | ||||

| 31.07.1969 | Mikoszewo, Poland | different grasses | ||||

| 05.08.1969 | Mikoszewo, Poland | Calamagrostis epigejos | ||||

| Eulecanium tiliae (Linnaeus, 1758) | 5 | AC | 02.05.2012 | Ruda Slaska, Poland | Acer platanoides | 50°15'24.12"N, 18°54'5.64"E |

| 16.05.2012 | Niegowonice, Poland | Tilia cordata | 50°23'55.69"N, 19°26'8.92"E | |||

| Luzulaspis frontalis Green, 1928 | 13 | KC | 06.1962 | Wolski Forest Cracov, Poland | Carex brizoides | |

| Luzulaspis nemorosa Koteja, 1966 | 15 | KC | 21.08.1967 | Ojcow Cracov, Poland | Luzula nemorosa | |

| Parthenolecanium corni (Bouché, 1844) | 6 | AC | 30.04.2007 | Ruda Slaska, Poland | Tilia cordata | 50°16' 5.24"N, 18°53'8.64"E |

| 07.05.2012 | Ruda Slaska, Poland | Ulmus laevis | 50°15'23.85"N, 18°54'6.42"E | |||

| Pulvinaria vitis (Linnaeus, 1758) | 31 | AC, KC | 29.08.1987 | Ruda Rozaniecka Roztocze , Poland | Salix sp. | |

| 26.08.1987 | Ruda Rozaniecka Roztocze, Poland | Betula verrucosa | ||||

| 21.08.2011 | Katowice, Poland | Alnus glutinosa | 50°14'3.77"N, 19°0'55.71"E | |||

| Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Boyer de Fonscolombe, 1834) | 6 | AC | 02.06.2012 | Kuznia Raciborska, Poland | Prunus spinosa | 50°12'9.02"N, 18°19'56.48"E |

| 16.05.2012 | Niegowonice, Poland | Prunus spinosa | 50°23'54.86"N, 19°26'15.78"E |

The method used for preparation of the wings was standardized, as suggested by

Photos of the wings were taken with a Nikon DN 100 camera unit on a Nikon stereomicroscopes SM2 1500.

Photos from scanning microscope were taken from a Hitachi S-3400N microscope and made in the Department of Materials Science of the Silesia University of Technology.

The brightness was individually adjusted in COREL DRAW X, subsequent editing included cleaning and cropping the photo. The studied wings were put between two cover glasses (glued together by small drops of transparent nail polish) and deposited with the original specimen.

The wings were also observed on whole specimens. In order to ensure that the colour patterns are stable, the wings on the unmounted specimens were observed in different arrangement against a black background, and viewed at different incident angles of the light, which was narrowly concentrated in one direction at a slight angle to the wings surface.

According to

The present study confirmed that WIPs are present on the dry, minute and semitransparent wings of male scale insects. SEM observations (Fig. 2, 3) showed that membrane of the scale insect wing is characterized by the presence of corrugations and microtrichia.

In case of Hymenoptera and Diptera such membrane corrugations and hair placement together with uneven membrane thickness form stable and taxon specific colour patterns.

Convex ridges of a corrugated wing membrane act as a dioptres to stabilize the interference reflection and eliminate the iridescence effect over a large range of light incidences, it means that provide optical stabilization to WIPs. According to

Among examined species all of them exhibited its own WIP which could be distinguished from that of other species. Among the species two main types of patterns could be distinguished: “horizontally striped pattern”, encountered on broad wings of species which

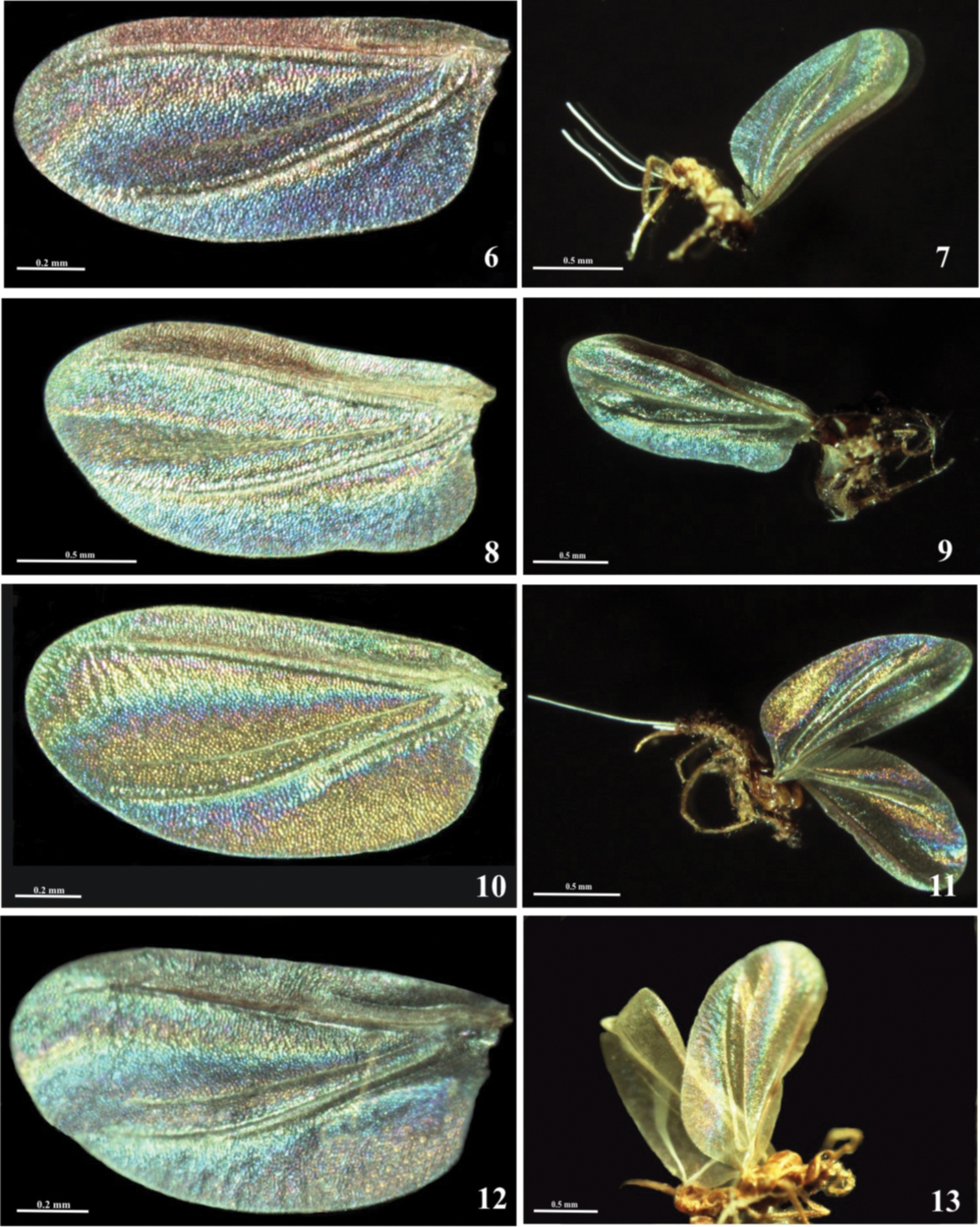

Males with “horizontally striped patterns” of WIPs, subfamilies Eulacaninae and Coccinae: 6–7 WIP of Sphaerolecanium prunastri (Boyer de Fonscolombe) 8–9 WIP of Eulecanium tiliae (Linnaeus) 10, 11 WIP of Pulvinaria vitis 12–13 WIP of Parthenolecanium corni (Bouché).

In Pulvinaria vitis (Figs 10, 11), the main part of the region delimited by cubital ridge, posterior wing margin and the margin near the wing base is golden-hued. The same golden color surrounds the first light line. To these golden-hued areas adjoin from above purple-blue stripes. The WIP of the Parthenolecanium corni (Figs 12, 13) is quite similar to that of Pulvinaria vitis but, in the former species, there is broad blue-purple band on the part which lies below the cubital ridge (in Pulvinaria vitis there is only narrow purple-blue stripe). Only narrow yellowish stripes surround the first light line (in Pulvinaria vitis there is broad golden band). But the purple-blue band which adjoins to golden-hued area (which surrounds the first light line in Pulvinaria vitis) here, in Parthenolecanium corni is much broader.

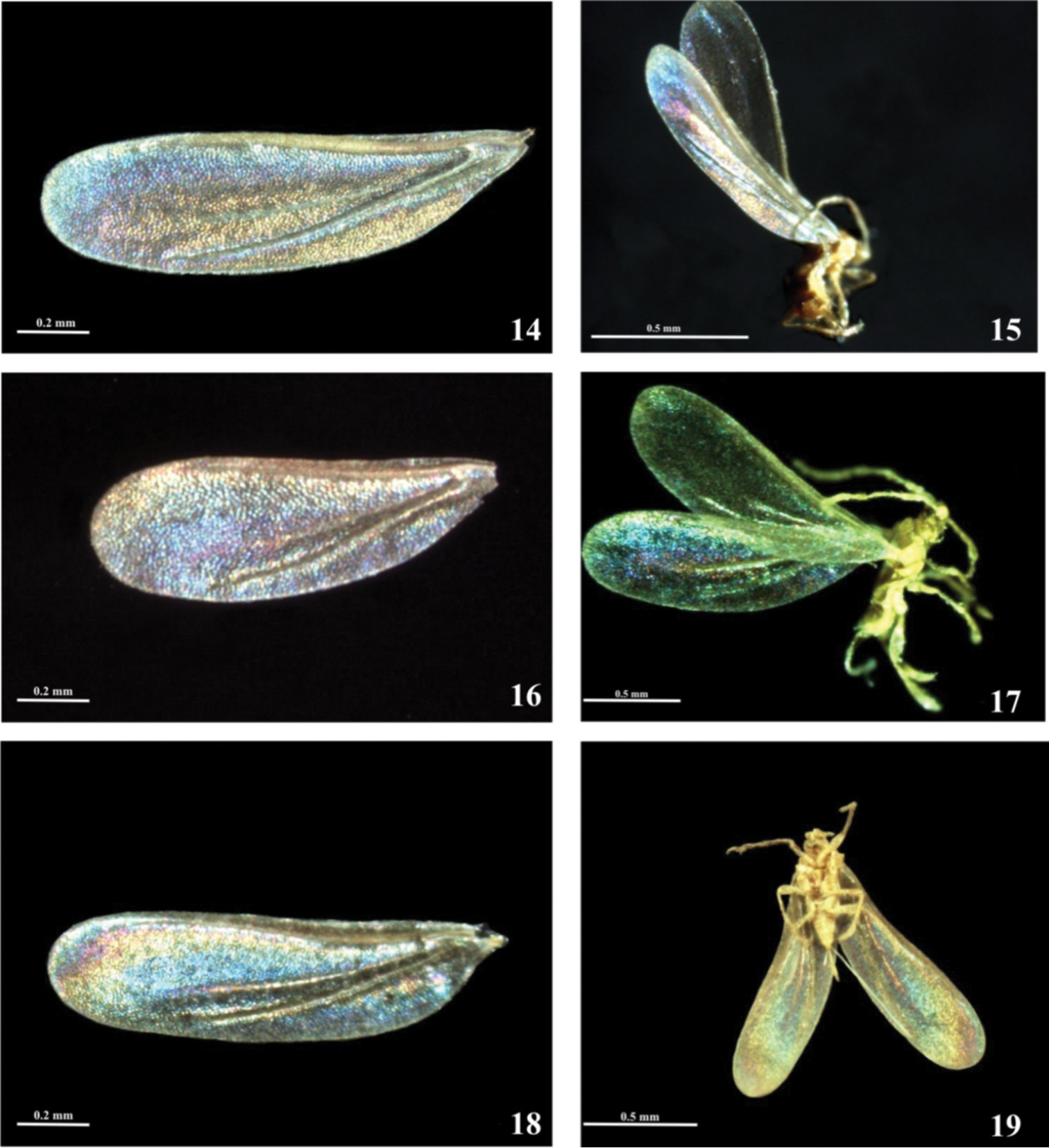

The pattern of the second type of WIP can be described as “ elliptical” - colours follow one by one, and do not form distinct stripes beneath the subcostal ridge which reach the apical margin of the wing, as in previous type.

This type of WIP is present on long and narrow wings of Eriopeltis lichtensteini, Luzulaspis frontalis and Luzulaspis nemorosa . The apical part of the wing is covered only by one colour. These two genera were grouped by Giliomee in the “Eriopeltis group” and in the subfamily Eriopeltinae by

Males with “eliptical” patterns of WIPs, subfamily Eriopeltinae: 14, 15 WIP of Luzulaspis frontalis Green 16–17 WIP of Luzulaspis nemorosa Koteja. 18–19 WIP of Eriopeltis lichtensteini Signoret.

In Luzulaspis nemoralis inner part, which surrounds the first light line is purple, than colour turns into blue and near the anterior edge of the wing is yellowish-green (Figs 16, 17). All part below the cubital ridge is purple-bluish. In Eriopeltis lichtensteini (Figs 18, 19) first light line and cubital ridge are surrounded by blue area. Near the subcostal ridge blue turns into yellowish green. Very characteristic is purple spot near the apical part of the wing.

The WIPs of each of these seven species are significantly different and could provide additional insights into species recognition. These colour patterns are stable and can be seen not only on horizontally arranged wings but also on hole specimen (Figs 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19), the only requirements are black background and proper illumination.

The use of wing interference patterns (WIPs) as a morphological character is so new that very little is known about their significance, either to the behavior of the species or in terms of morphological taxonomy, although they have already proven to be useful for generic- and even species–level classifications, particularly in Hymenoptera (

In other insect groups, such as Diptera and Hymenoptera, it is believed that WIPs are not only a byproduct of physical traits, but probably also function in intra- and interspecific signaling. Thus wing display play a central role in visual courtship communication in several groups of Diptera (e.g. Sepsidae, Tephritidae) and Hymenoptera (e.g. Chalcidoidea: Pteromalidae) (

At the present time, in geological history only male Coccoidea possess wings. Females are often sedentary, only have simple unicorneal eyes and all are completely apterous. It seems, therefore, unlikely that these females are able to see sophisticated colour patterns on male’s wings. However

Interestingly,

The types of WIPs seen in this study appear to reflect the affinity between the members of Coccidae. Indeed, the types of WIPs found here might be connected with their ecology, in so far as the “horizontally striped pattern” occurs in species which are present on woody plants: Sphaerolecanium prunastri feeds mainly on representatives of Rosaceae, and Eulecanium tiliae, Parthenolecanium corni and Pulvinaria vitis are common poliphagous species also encountered on different woody host plants (

According to

On the basis of the examined material, the WIPs of male Coccids appear to be uniform among conspecifics. However, more material from different localities and from different host plants, etc need to be studied to know if there is any intraspecific variability or phenotypical plasticity. If WIPs are used by their bearers for visual communication and, if this signalling system is involved in reproductive isolation and species recognition (

The importance of the adult male structure for the proper understanding of the relationships within the Coccoidea was recognized by

If the usage of WIPs in coccidology becomes as useful as in the studies on Hymenoptera and Diptera, it will be very important to keep the wings under dry conditions. At present, the most common method of specimen storage prior to making microscopic slides is to preserve the specimens in ethanol. Unfortunately, the WIP colour patterns are invisible on specimens mounted in Canada balsam, while scale insect wings which have been preserved in alcohol either do not show WIPs at all or the patterns are not as bright and clear as those using dry wings.

For a long time, wings of scale insects have been regarded as being poor in morphological features because of their reduced venation and lack of pigments. WIPs might be an additional trait for facilitating species identification. Because studies on scale insect wings are easy and cheap, studies of the wing interference patterns might be a helpful tool in species recognition and for clarifying many taxonomic problems, together with very important and common molecular techniques (

These preliminary studies confirmed the presence of stable and taxonomically specific wing intereference patterns (WIPs) on scale insects wings. The thin wings of males display vivid structural colour patterns due to thin film interference when viewed against black background using white light. The use of WIPs as a species character in the species studied here has produced some convincing patterns and therefore these small, semitransparent organs should not be regarded as unimportant features anymore. However, if WIPs on male wings are to be studied, it is imperative that are stored dry and not preserved in ethanol or mounted in Canada balsam.

It is intended that these studies will continue, using a wide range of species from different scale insect families and also to consider any effects of intraspecific variation and phenotypic plasticity.

I thank dr Jacek Szwedo from Museum and Institute of Zoology (Polish Academy of Science) and dr Ewa Mróz from Department of Zoology (University of Silesia) for all their comments and suggestion and their valuable help.