(C) 2013 Donald W. Buden. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Buden DW, Helgen KM, Wiles GJ (2013) Taxonomy, distribution, and natural history of flying foxes (Chiroptera, Pteropodidae) in the Mortlock Islands and Chuuk State, Caroline Islands. ZooKeys 345: 97–135. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.345.5840

The taxonomy, biology, and population status of flying foxes (Pteropus spp.) remain little investigated in the Caroline Islands, Micronesia, where multiple endemic taxa occur. Our study evaluated the taxonomic relationships between the flying foxes of the Mortlock Islands (a subgroup of the Carolines) and two closely related taxa from elsewhere in the region, and involved the first ever field study of the Mortlock population. Through a review of historical literature, the name Pteropus pelagicus Kittlitz, 1836 is resurrected to replace the prevailing but younger name Pteropus phaeocephalus Thomas, 1882 for the flying fox of the Mortlocks. On the basis of cranial and external morphological comparisons, Pteropus pelagicus is united taxonomically with Pteropus insularis “Hombron and Jacquinot, 1842” (with authority herein emended to

Pteropus phaeocephalus, P. pelagicus, P. insularis, P. tokudae, Mortlock Islands, Chuuk, Micronesia, atoll, taxonomy, distribution, status, natural history, climate change, sea level rise

Many islands of the west-central Pacific Ocean remain poorly known biologically, particularly the numerous, small, low-lying, coralline atolls and atoll-like islands of Micronesia. Their inaccessibility and relatively depauperate biotas (compared with those of larger and higher islands) have contributed to a paucity of visiting biologists. However, an understanding of the biogeography and biodiversity of Oceania remains incomplete without knowledge of the species that inhabit these miniscule lands.

The genus Pteropus is comprised of about 65 species of flying foxes, making it by far the largest genus in the family Pteropodidae (

Although Pteropus phaeocephalus Thomas, 1882 was originally described as a distinct species endemic to the Mortlock Islands, a group of atolls in central Micronesia, there has long been recognition of the similarity between this form and Pteropus insularis, which is restricted to the neighboring main islands and barrier reef islands of Chuuk Lagoon and Namonuito Atoll located 171 km to the northwest (

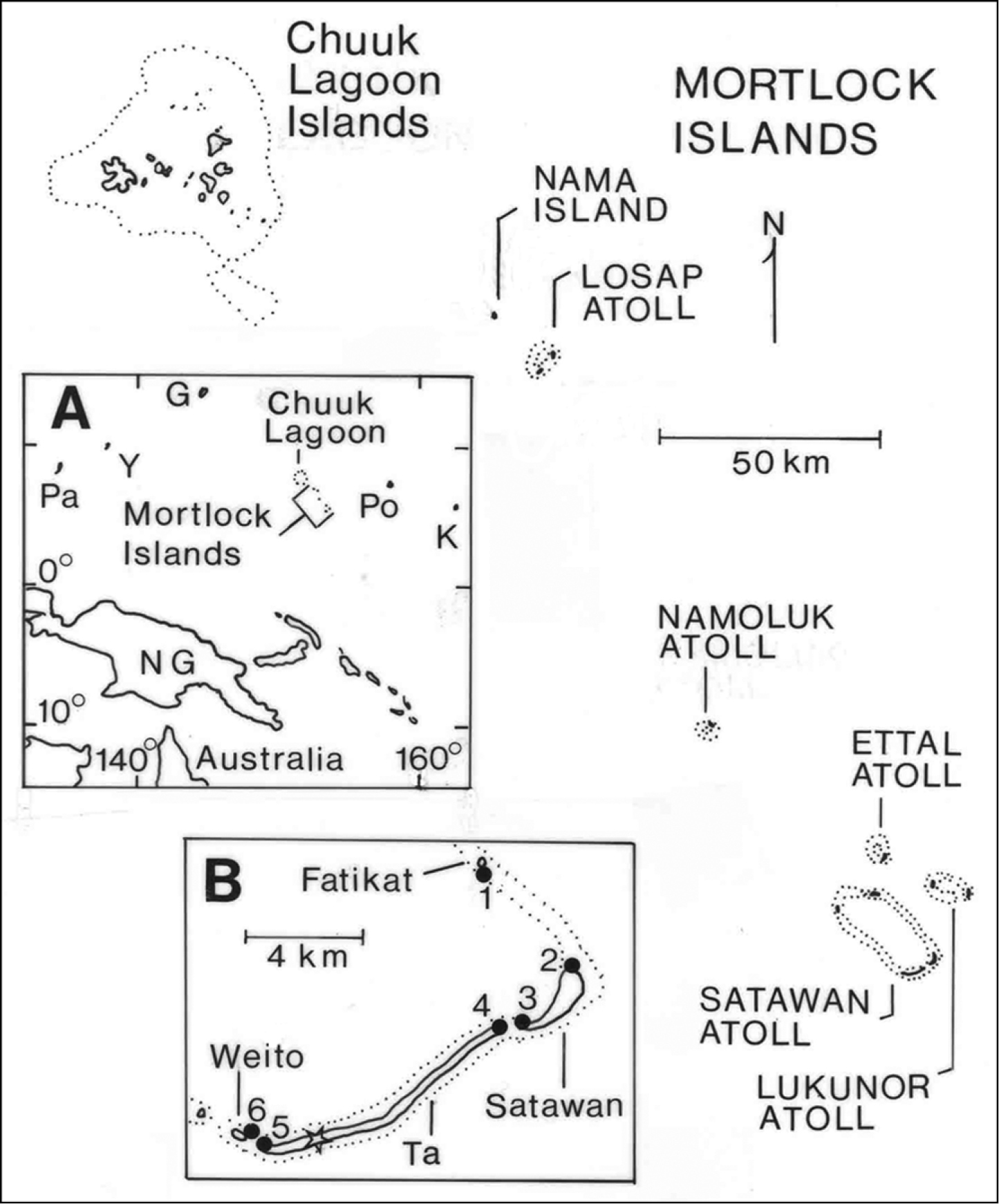

The Mortlock Islands (07°00'N, 152°35'E to 05°17'N, 153°39'E) are a part of Chuuk (formerly Truk) State, one of four states comprising the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), the others being Yap, Pohnpei, and Kosrae. The FSM together with the Republic of Belau (Palau) make up the Caroline Islands in the tropical western Pacific Ocean. The Mortlocks are a chain of five atolls and one low, coral island spanning 224 km (Figure 1). Land area totals 11.9 km2, distributed among more than 100 islands; Ta, Satawan Atoll, is the largest island (Table 1). Maximum elevations are only 3–5 m asl. Over the years, a confusing array of alternative names and spellings has been proposed for different islands and island groups in the Mortlocks and Chuuk Lagoon (

Location map for the Mortlock Islands and Chuuk Lagoon, Micronesia. Inset A location of islands in the west-central Pacific Ocean, G = Guam, K = Kosrae, NG = New Guinea, Pa = Palau, Po = Pohnpei, Y = Yap; inset B southern end of Satawan Atoll, solid circles indicate beach sites where interisland movement of flying foxes was assessed (see Table 5) and the open star indicates the airport station count site on Ta Island.

Statistical data for the Mortlock Islands, Chuuk State, Federated States of Micronesia.

| Island group | Land area (km2)a | Number of islands | Largest island (km2)a | Number of inhabited islands | Number of residentsb | Distance to next atoll (km)c | Observation daysd |

| Northern Mortlocks | |||||||

| Nama Island | 0.75 | 1 | Nama (0.75) | 1 | 995 | 14 | 7 |

| Losap Atoll | 1.03 | 10 | Lewel (0.56) | 2 | 875 | 110 | 1 |

| Central Mortlocks | |||||||

| Namoluk Atoll | 0.83 | 5 | Namoluk (0.31) | 1 | 407 | 53 | 11 |

| Southern Mortlocks | |||||||

| Ettal Atoll | 1.89 | 20e | Ettal (0.97) | 1 | 267 | 7 | 3 |

| Satawan Atoll | 4.59 | 65f | Ta (1.55) | 4 | 2, 935 | 8 | 70 |

| Lukunor Atoll | 2.82 | 18 | Lekiniochg (1.28) | 2 | 1, 432 | - | 26 |

a From

The Mortlocks fall within the equatorial rainbelt and are wet enough to support mesophytic vegetation (

All six island groups comprising the Mortlocks are inhabited, but only 1–4 islands in each group have permanent settlements (Table 1). The other islands are visited by atoll residents with varying degrees of frequency to cultivate taro or to gather coconuts, crabs, and other forest and coastal commodities. A total of 6, 911 people lived in the Mortlocks in 2000, representing a density of 581 people per km2.

Museum specimens utilized in this study are deposited in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA (AMNH), the Academy of Natural Sciences, Drexel University, Philadelphia, USA (ANSP), the Natural History Museum, London, UK (BMNH), Brigham Young University-Hawaii Campus, Laie, Hawaii, USA (BYUH), College of Micronesia-FSM, Kolonia, Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia (COM), the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA (MCZ), the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France (MNHN), the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA (USNM), and the Museum für Naturkunde, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany (ZMB).

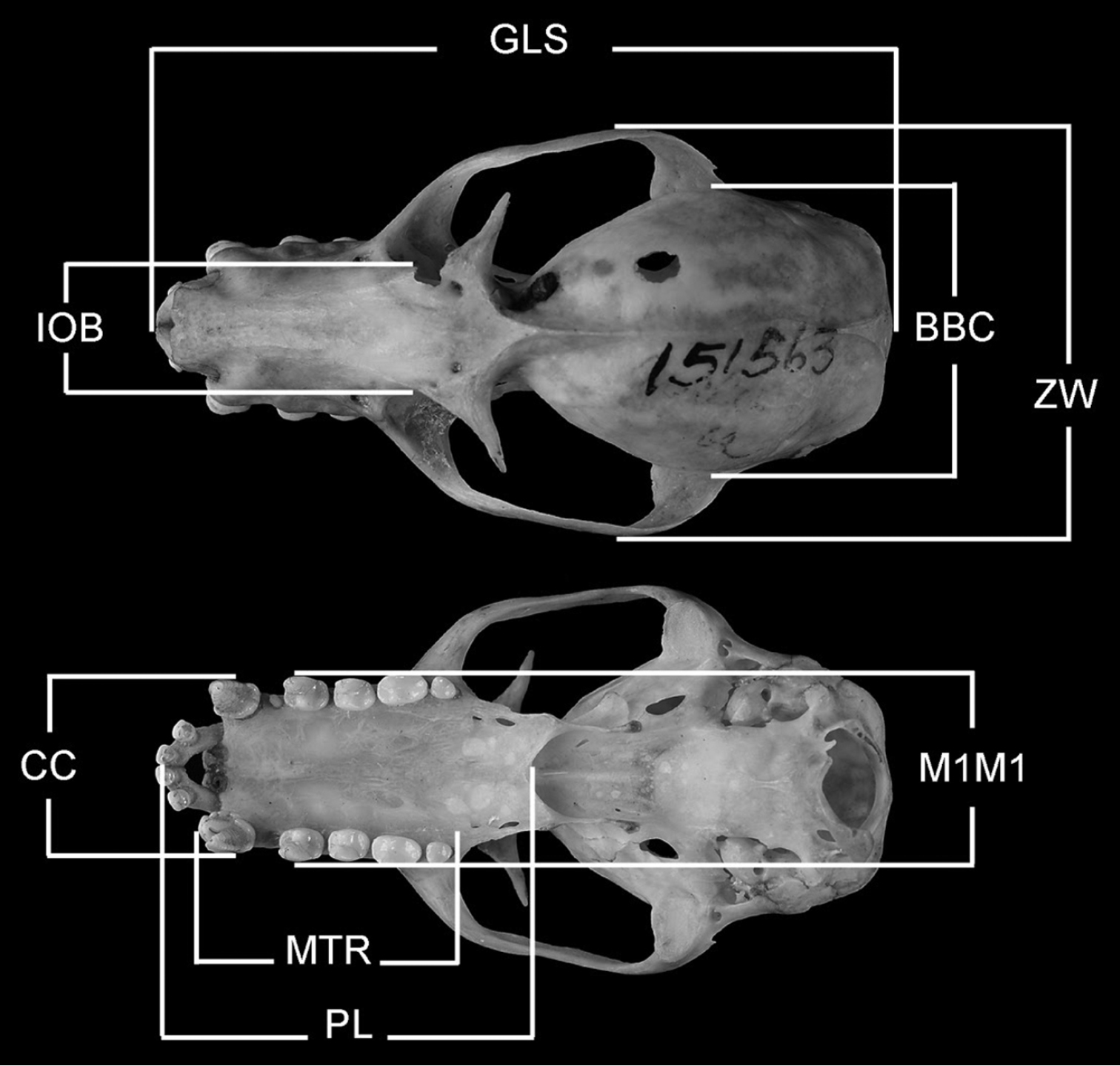

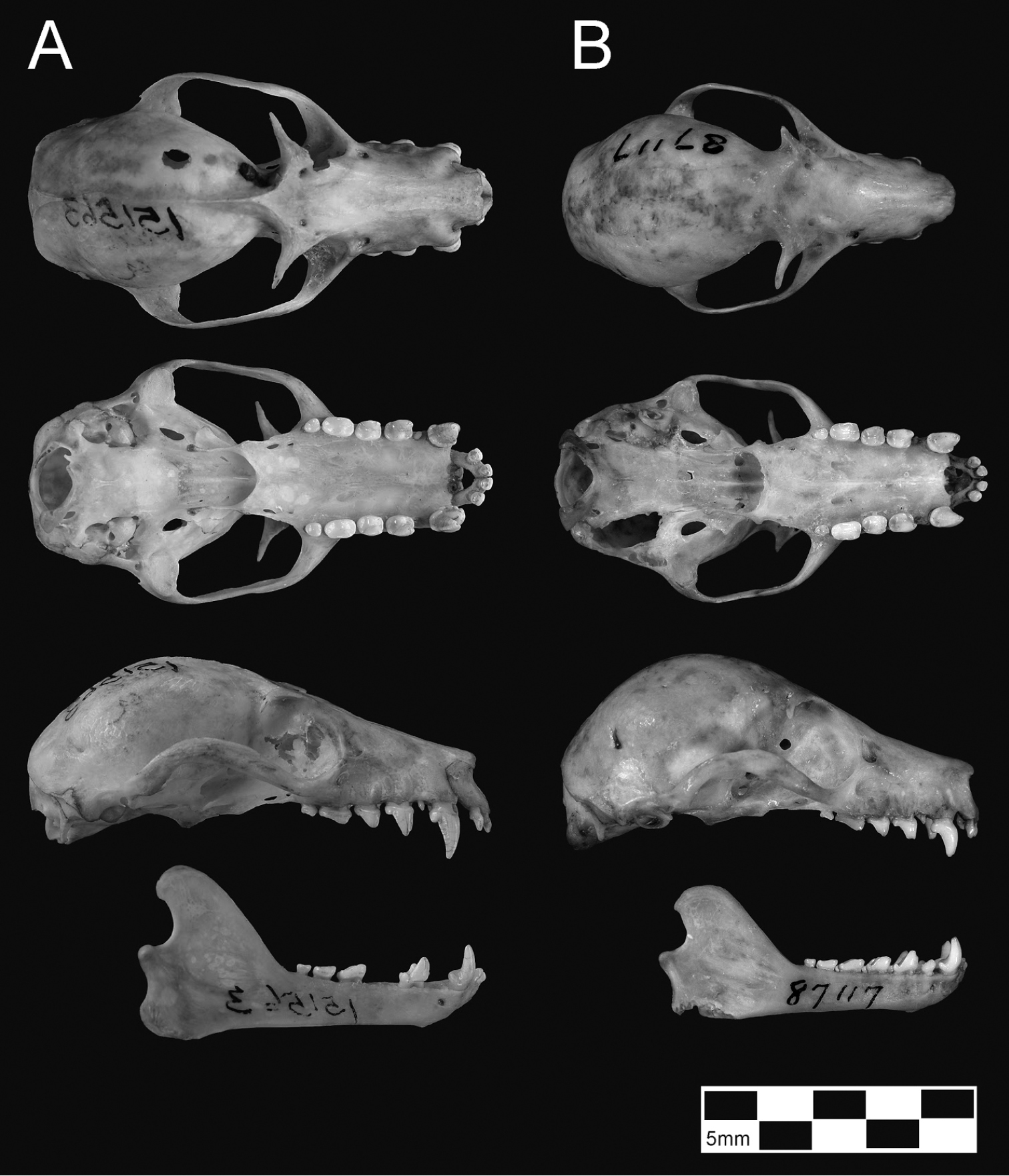

Measurements of specimens are in millimeters and grams. Cranial and forearm measurements were taken on museum specimens (skins, skulls, and fluid preserved specimens) using dial calipers. Cranial measurements (see Figure 2) are abbreviated (and defined) as follows: GLS (greatest length of skull; distance from posterior midpoint on occipital crest to anterior midpoint of premaxillae); PL (palate length; distance from anterior midpoint of premaxillae to posterior midpoint of bony palate); ZW (greatest width across the zygomatic arches); IOB (width of interorbital constriction); BBC (breadth of braincase, measured across the braincase at squamosal bases); MTR (length of maxillary toothrow, alveolar distance from anterior root of canine to posterior root of last molar); CC (external, alveolar distance across upper canines); M1M1 (external, alveolar distance across upper first upper molars). Head-body length (snout to rump) and ear length were measured with a millimeter ruler on fresh material or recorded from museum specimen labels. Body mass was obtained from fresh specimens using Pesola scales or recorded from specimen labels. Immatures are defined as neonates to young weighing ≤100 g. Subadults are defined as adult-sized or nearly adult-sized young with incompletely fused skull sutures/synchondroses (cf.

Cranial measurements employed in this study. See Methods for abbreviations.

Standard descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and observed range) were calculated for the samples of populations and species listed in the tables. Only cranial and dental measurements were incorporated in the multivariate analyses. Principal component analyses were computed using the combination of cranial and dental measurements indicated in tables and in the text. All measurement values were transformed to natural logarithms prior to multivariate analysis. Principal components were extracted from a covariance matrix. Variables for multivariate analyses were selected judiciously to maximize sample sizes for comparison by allowing for inclusion of partially broken skulls in some cases. The software program Statistica 8.0 (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA) was used for multivariate analysis.

Field work for this study began as part of a biological survey of terrestrial vertebrates and selected insect groups on Satawan Atoll, but was expanded in 2004 to include broader population assessments of flying foxes and other wildlife in the Mortlocks. Field surveys were conducted on Satawan Atoll during 17–26 December 2002, 7 July–1 August 2003, 30 March–9 April 2004, 22 June–6 July 2004, and 1–5 August 2004. The five other groups of islands were visited in 2004: Nama Island, 7–14 July; Losap Atoll, 10 July; Namoluk Atoll, 19–29 July; Ettal Atoll, 30 July–1 August; and Lukunor Atoll (Lekinioch Island only), 2–3 August. In 2012, incidental observations were made at Lukunor Atoll, 20 June–15 July, and Satawan Atoll, 15–17 July. All field work was conducted by DWB.

Information on the abundance and biology of bats came from a combination of sources. Station counts of flying bats were conducted on Satawan Atoll at two types of locations providing relatively unobstructed views of the sky: the Ta airport and six beach sites where interisland movement of bats was assessed (Figure 1). These counts were made by a single person at sunrise or sunset, lasted 25–95 minutes, and were made once or twice per time period at each station except for multiple counts at the Ta airport.

Flying foxes (and other wildlife) were also counted during walks conducted from mid-morning to mid- to late afternoon. These were made along pre-existing trails or by following a compass bearing through the center of less frequently visited islands, usually along the long axis of an island, but occasionally at right angles to it. Each route was surveyed only once. Care was taken to avoid double counting bats flushed by the observer. An undetermined, but probably substantial, proportion of roosting bats was hidden from view by the relatively dense forest canopy. Roosting flying foxes were viewed with 10x binoculars to observe behavior and search for the presence of young. Other information on bats was obtained from incidental observations and atoll residents. We did not search for feeding evidence of bats (i.e., discarded fruit, chewed pellets, fecal splats). An estimate of the number of flying foxes on each atoll was made based on: 1) overall numbers of bats seen, 2) percentage of each atoll covered by the observer, 3) the quality and amount of forest on an atoll, and 4) information provided by island residents, especially for Namoluk, Ettal, and Lukunor Atolls.

Pteropus pelagicus Kittlitz, 1836 Taxonomic history

The Russian research vessel Senyavin, under command of Friedrich [Feodor] Lütke, and with F. H. von Kittlitz as one of the ship’s naturalists, was in the eastern Caroline Islands early in 1828 (

The holotype of Pteropus phaeocephalus is labeled as collected by Kubary in the Mortlock Islands, but the date and the name of the island are unstated. Kubary traveled widely in the Pacific while employed as a naturalist and ethnographer by the Godeffroy Museum (

Kubary returned to the Mortlocks in 1877. In a separate and anonymously written introduction to the ethnography that Kubary apparently sent to L. Friederichsen, editor of Mittheilungen der Geographischen Gesellschaft in Hamburg, the author (L. Friederichsen?) or authors (in

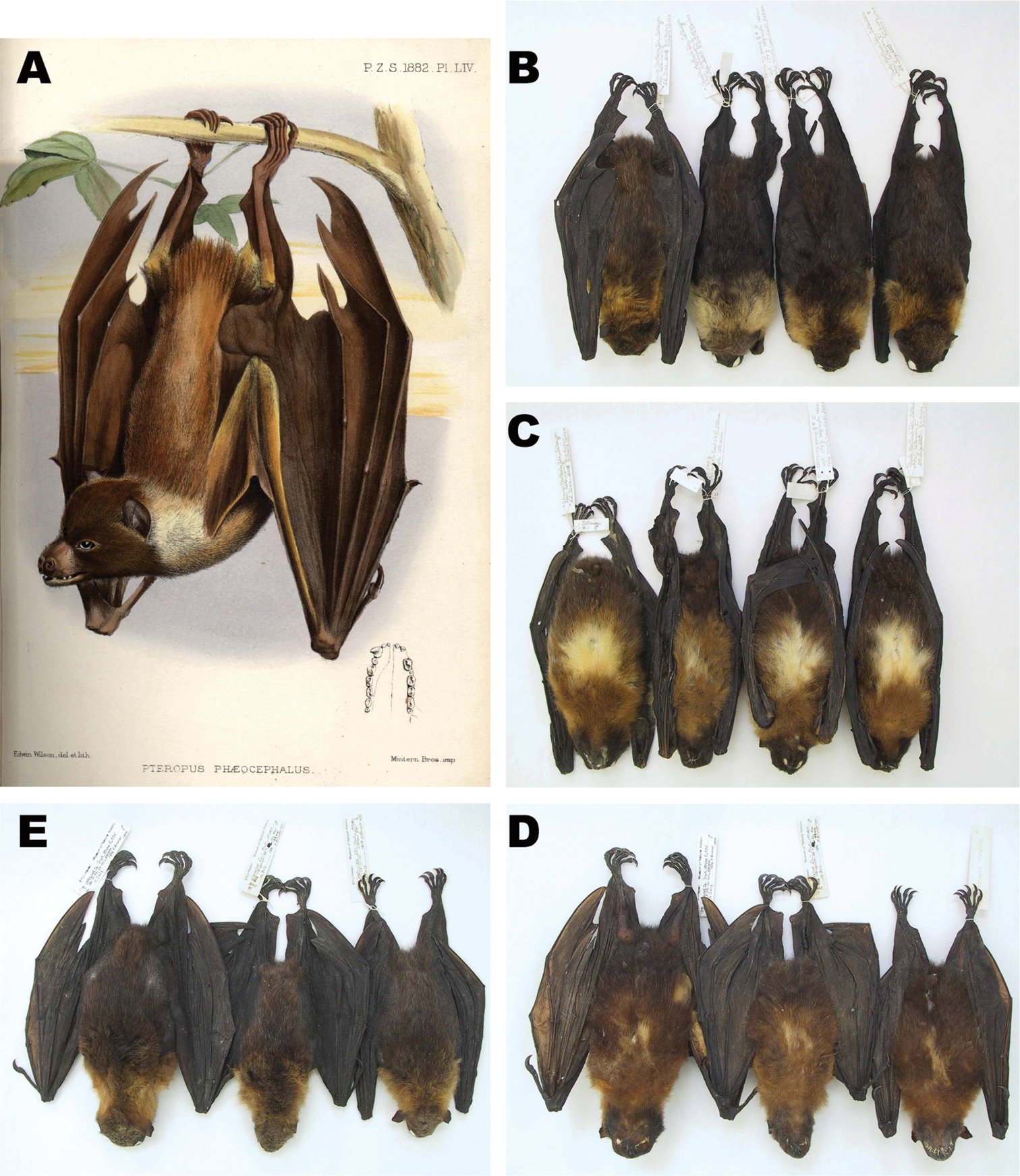

Among the 11 specimens from Satawan Atoll, the mantle ranges from creamy white to deep buff or tawny in adults and subadults, and is grayish brown (without yellowish or reddish highlights) in immatures. It averages darker (more tawny, less pale buff) in the six adults from Namoluk Atoll. In all Mortlock specimens, the mantle is bisected by a narrow to broad area of darker (brown) pigmentation, which, in some cases, gives the appearance of having pale shoulder patches. In specimens from both Namoluk and Satawan, the back and rump are dark brown (occasionally tinged with reddish brown in Satawan specimens), with scattered pale-tipped hairs; Namoluk specimens average slightly darker than those from Satawan. In both the Namoluk and Satawan material, the face is dark brown to nearly black and with varying amounts of grizzling. The top of the head is brown or grayish brown. The venter is usually light brown to pale reddish brown anteriorly (on throat and chest) and dark brown posteriorly; subadults are more uniformly light brown. A large prominent white or pale yellowish white patch, 20–40 mm wide, occurs midventrally in most specimens (Figure 3C); it is occasionally slightly reduced or nearly obsolete.

(A) Scanned image of Plate LIV from original description of Pteropus phaeocephalus

Mortlock Islands specimens generally match the color descriptions of the holotype of phaeocephalus as described by

Compared with a sample of five specimens of Pteropus insularis, all presumably from Chuuk Lagoon (four from Weno, one [MCZ 7023] of uncertain origin), the Mortlock Islands bats tend to show greater contrast between the paler coloration of the mantle and the darker pigmentation on the back and rump. The midventral pale patch is consistently larger in the Mortlock specimens that we examined, although

Mensural data for samples of flying foxes from Chuuk Lagoon islands and the Mortlock Islands; data sets include range, n in parentheses, and mean ± SD; all measurements are in millimeters or grams.

| Mortlock Islands | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character | Sex | “Truk”a | Chuuk Lagoon islands | Namoluk Atoll | Satawan Atoll |

| Head-body length | ♂ | ____ | 168.0–186.0 (2)177.0 ± 12.73 | 158.0 (1) | 150.0–170.0 (2)160.0 ± 14.0 |

| ♀ | 165.0 (1) | 131.0 (1) | 155.0–170.0 (5)163.0 ± 6.08 | 155.0–170.0 (4)161.3 ± 6.29 | |

| Forearm length | ♂ | ____ | 101.0 (1) | 103.9 (1) | 102.0–108.7 (2)105.4 ± 4.74 |

| ♀ | 104.8 (1) | ____ | 102.3–107.3 (5)104.6 ± 2.18 | 103.2–108.0 (5)105.3 ± 1.78 | |

| Ear length | ♂ | 20.0–22.0 (2)21.0 ± 1.41 | 23.0 (1) | 24.0 (1) | |

| ♀ | ____ | ____ | 23.0–24.0 (3)23.7 ± 0.58 | 22.0–23.0 (2)22.5 ± 4.74 | |

| Body mass | ♂ | ____ | 148.0–200.0 (2)174.0 ± 36.76 | 175.0 (1) | 142.0–203.0 (2)172.5 ± 43.1 |

| ♀ | 170.0 (1) | 150.0 (1) | 190.0–225.0 (5)211.0 ± 13.87 | 153.0–187.0 (4)171.8 ± 12.28 | |

| Greatest skull length (GLS) | ♂ | 43.9–46.1 (5)44.8 ± 0.18 | 44.6 (1) | 45.0 (1) | 47.2 (1) |

| ♀ | 44.0–45.4 (5)44.7 ± 0.53 | 44.1 (1) | 45.3–46.1 (2)45.7 ± 0.57 | 45.0–46.6 (4)45.7 ± 0.59 | |

| Palate length (PL) | ♂ | 22.6–24.0 (5)23.0 ± 0.59 | 22.2 (1) | 23.3 (1) | 22.0–24.4 (2)23.2 ± 1.70 |

| ♀ | 22.0–24.0 (6)22.8 ± 0.75 | 22.9 (1) | 23.0–24.0 (2)23.5 ± 0.71 | 23.2–24.1 (3)23.9 ± 0.59 | |

| Maxillary toothrow (MTR) | ♂ | 14.8–15.2 (5)15.1 ± 0.17 | 15.1–15.2 (2)15.2 ± 0.70 | 15.5 (1) | 15.2–15.8 (2)15.6 ± 0.50 |

| ♀ | 15.0–15.5 (6)15.2 ± 0.19 | 14.8 (1) | 14.8–15.5 (3)15.2 ± 0.36 | 15.0–15.5 (4)15.2 ± 0.24 | |

| Breadth of braincase (BBC) | ♂ | 17.2–17.6 (5)17.4 ± 0.15 | 17.3 (2) | 18.0 (1) | 17.6–18.2 (2)17.9 ± 0.42 |

| ♀ | 17.0–17.8 (6)17.5 ± 0.33 | 17.0 (1) | 17.9–18.1 (2)18.0 ± 0.14 | 17.5–18.1 (4)17.9 ± 0.26 | |

| Breadth across canines (CC) | ♂ | 10.0–11.0 (5)10.4 ± 0.44 | 10.8–11.1 (2)11.0 ± 0.21 | 11.1 (1) | 10.7–11.9 (2)11.3 ± 0.85 |

| ♀ | 9.6–10.8 (6)10.4 ± 0.41 | 9.9 (1) | 11.0–11.4 (3)11.2 ± 0.21 | 10.9–11.1 (4)11.0 ± 0.10 | |

| Breadth across M1 (M1M1) | ♂ | 12.0–12.5 (4)12.3 ± 0.22 | 12.2 (2) | 12.0 (1) | 12.3–12.9 (2)12.6 ± 0.42 |

| ♀ | 12.1–12.8 (5)12.3 ± 0.29 | 12.0 (1) | 11.9–12.3 (3)12.1 ± 0.21 | 12.3–12.8 (3)12.6 ± 0.26) | |

| Interorbital breadth (IOB) | ♂ | 7.0–7.4 (4)7.2 ± 0.17 | 7.5 (1) | 7.5 (1) | 7.1–7.6 (2)7.4 ± 0.35 |

| ♀ | 7.0–7.4 (6)7.2 ± 0.14 | 7.2 (1) | 7.7–8.0 (3)7.8 ± 0.15 | 7.7–7.8 (3)7.8 ± 0.06 | |

| Zygomatic width (ZW) | ♂ | 23.0–25.4 (4)24.1 ± 0.95 | 24.0–27.0 (2)25.5 ± 2.21 | 25.6 (1) | 23.9–27.1 (2)25.5 ± 2.26 |

| ♀ | 23.6–25.4 (5)24.5 ± 0.65 | ____ | 25.7–26.0 (2)25.9 ± 0.21 | 25.2–25.6 (3)25.4 ± 0.20 | |

a Specimens confiscated on Guam, but originated from Chuuk State. Most were probably collected on islands in the Chuuk Lagoon, but some may have come from outer atolls, including the Mortlocks.

The type series of Pteropus laniger, originally described as Pteropus lanigera [sic]by H.

Overall pelage coloration of the two available skins of Pteropus tokudae (e.g. Figure 4; see further discussion below) is generally similar to that of Pteropus phaeocephalus insularis, perhaps averaging somewhat darker overall (

Holotype skin of Pteropus tokudae. AMNH 87117, adult male, from Guam, collected 10 Aug 1931 by W.F. Coultas. Scale bar = 25 mm.

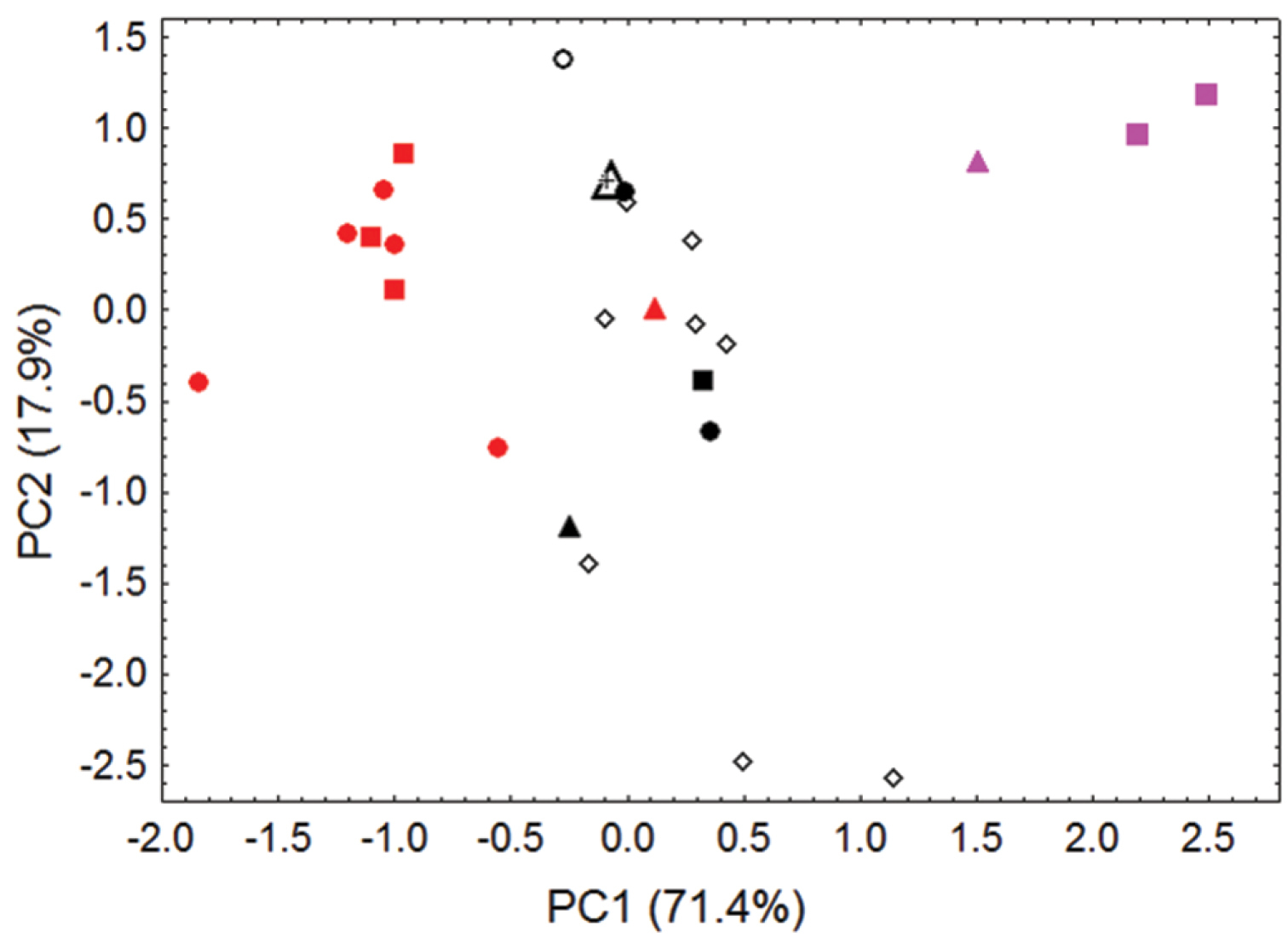

Our study of essentially all available museum specimens of Pteropus from the islands of Chuuk Lagoon, Namonuito Atoll, and the Mortlocks, including the newly collected Mortlock material reported here, allowed us to examine patterns of multivariate craniometric variation in Pteropus from these archipelagos using Principal Component Analyses (PCA). We also included in these comparisons the three available skulls of Pteropus tokudae Tate, 1934, of Guam (a species that apparently became extinct in the late twentieth century:

The type of pelagicus can no longer be traced (see above), and the skulls of the surviving type specimens for the other relevant taxa in this group (insularis [MNHN 1996-2112, syntype of insularis, designated here as the lectotype of insularis based on being the only skull available from the type series], phaeocephalus [BMNH 82.10.27.4, holotype], laniger [USNM 37815, lectotype], and tokudae [AMNH 87117, holotype] are all somewhat broken. Consequently, we based our PCA comparisons on a relatively small number of five variables (Table 4, Figure 5) to allow for the inclusion of these various type specimens, as well as various other museum specimens (adult skulls at AMNH, ANSP, BMNH, COM, MNHN, USNM, and ZMB), many of which are also partially broken.

Cranial measurements (mean ± SD, in millimeters, n in parentheses) for pooled samples of flying foxes from Chuuk Lagoon islands versus Mortlock Islandsa.

| Character | Chuuk Lagoonb | Mortlock Islands | t | df | P |

| Greatest skull length | 44.8 ± 0.63 (12) | 45.9 ± 0.80 (6) | -3.37 | 18 | 0.003 |

| Palate length | 22.8 ± 0.64 (13) | 23.5 ± 0.82 (8) | -2.22 | 19 | 0.039 |

| Maxillary toothrow | 15.1 ± 0.18 (14) | 15.3 ± 0.32 (10) | -1.93 | 22 | 0.066 |

| Breadth of braincase | 17.4 ± 0.26 (14) | 17.9 ± 0.24 (9) | -4.88 | 21 | 0.000 |

| Breadth across canines | 10.5 ± 0.44 (14) | 11.1 ± 0.34 (10) | -3.93 | 22 | 0.001 |

| Breadth across M1 | 12.4 ± 0.30 (12) | 12.3 ± 0.36 (9) | 0.21 | 19 | 0.834 |

| Interorbital breadth | 7.2 ± 0.16 (12) | 7.7 ± 0.26 (9) | -4.83 | 19 | 0.000 |

| Zygomatic width | 24.5 ± 1.07 (11) | 25.6 ± 0.89 (8) | -2.21 | 17 | 0.041 |

a Unpooled sample statistics are in Table 2. b Includes AMNH specimens confiscated on Guam.

Morphometric separation (first two principal components of a Principal Components Analysis) of 27 adult skulls of Pteropus pelagicus and Pteropus tokudae. These comparisons involve 5 measurements (maxillary toothrow length, breadth of braincase, external breadth of rostrum across canines, external breadth of palate across first upper molars, and least interorbital breadth). The first principal component mainly reflects distinctions in overall skull size, which increases from right to left. Specimens of Pteropus pelagicus pelagicus from the Mortlock Islandsare denoted by red symbols (including the red triangle, the holotype of phaeocephalus from “Mortlock Islands”; red circles, Satawan Atoll; and red squares, Namoluk Atoll). Specimens of Pteropus pelagicus insularis are denoted by black symbols; closed black symbols indicate samples of known geographic origin (including the closed black triangle, the holotype of insularis from “Ruck”; closed black circles, specimens labeled “Ruck”; closed black square, specimen labeled “Uala” (= Weno); and black cross, specimen from Namonuito Atoll) and open symbols indicate specimens of imprecise geographic origin (including the large open triangle, the lectotype of laniger, erroneously attributed to the “Samoa Islands” in the original description; open black circle, an unprovenanced specimen from ANSP; and open black diamonds, specimens at AMNH seized on Guam but originating from Chuuk State). Specimens of the closely related species Pteropus tokudae from Guam are denoted by pink symbols (including the pink triangle, the holotype of tokudae from Guam, and the pink squares, other specimens from Guam).

Our craniometric comparisons (Figure 5, Table 4) indicate that skulls from the Mortlock Islands (pelagicus), from the islands of Chuuk Lagoon and Namonuito Atoll (insularis), and from Guam (tokudae), separate primarily along the first principal component (representing 71% of the variance), mainly reflecting differences in overall skull size between these insular populations/taxa.

Factor loadings, eigenvalues, and percentage of variance explained by illustrated components (Figure 5) from Principal Components Analysis of 27 adult skulls of Pteropus pelagicus and Pteropus tokudae (see “specimens examined”). Principal components are extracted from acovariance matrix of 5 log-transformed cranialmeasurements (see Figures 2 and 5, Tables 2–3).

| Variable | PC1 | PC2 |

|---|---|---|

| Interorbital width | -0.587 | 0.798 |

| Breadth of braincase | -0.869 | -0.121 |

| Maxillary toothrow length | -0.911 | -0.163 |

| Breadth across canines | -0.972 | -0.105 |

| Breadth across M1s | -0.711 | -0.368 |

| Eigenvalue | 0.013 | 0.003 |

| Percent variance | 71.4% | 17.9% |

Several points are of special note. First, specimens of tokudae separate cleanly from pelagicus/insularis, chiefly on the basis of their consistently smaller size (showing no overlap with Pteropus pelagicus in most skull measurements). Pteropus tokudae has a markedly smaller skull (greatest length 41.2–42.2 mm) with a relatively shorter and narrower rostrum compared to Pteropus pelagicus (Figure 6).

Skulls of Pteropus pelagicus (A Pteropus phaeocephalus insularis, USNM 151563, unsexed adult, from Uala [= Weno]; note last lower premolars missing in lower jaw) and Pteropus tokudae (B AMNH 87117, holotype of tokudae, adult male, from Guam). Scale bar = 25 mm.

Second, some overlap in morphometric space characterizes samples of pelagicus (skulls generally larger)and insularis (skulls generally smaller), especially with regard to the holotype of Pteropus phaeocephalus, which associates more closely with Chuuk Lagoon and Namonuito specimens than with more recent Mortlock samples. Chuuk Lagoon and Namonuito specimens tend to average slightly smaller in most measurements than Mortlock specimens (Table 2), but sample sizes are small. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found in six of eight cranial measurements when samples from different localities were pooled and sexes combined (Tables 2–3); ranges overlap in all measurements.

The only available skull from Namonuito Atoll (BMNH 15.1.18.1) shows closest association with specimens from Chuuk Lagoon (Figure 5), an indication that the flying fox population of Namonuito, the taxonomic position of which has not previously been analyzed and has been considered uncertain (

Our search for museum material of Pteropus phaeocephalus pelagicus and Pteropus phaeocephalus insularis uncovered one additional very interesting and largely overlooked museum specimen. This is a broken skull of a flying fox much larger than Pteropus phaeocephalus insularis, received from Otto Finsch, probably in 1880 (when he was in the Caroline Islands during his first Pacific expedition), and labeled “Ruck” (= Chuuk). This specimen (ZMB 5697) was misidentified as Pteropus insularis by

The name Pteropus pelagicus Kittlitz, 1836 is a senior synonym of the younger but prevailing name Pteropus phaeocephalus Thomas, 1882. Kittlitz’s name is listed in

In view of the very close similarity in body size and cranial features and measurements between specimens from Chuuk Lagoon islands (Pteropus insularis) and those from the Mortlocks Islands (Pteropus pelagicus), we include Pteropus insularis Jacquinot and Pucheran, 1853 (herein emended from Hombron and Jacquinot, 1842 – see remarks on authorship, this account) in Pteropus pelagicus and treat the two former monotypic species as subspecies – Pteropus phaeocephalus pelagicus Kittlitz, 1836 in the Mortlock Islands (synonym phaeocephalus Thomas, 1882) and Pteropus phaeocephalus insularis Jacquinot & Pucheran, 1853 on Chuuk Lagoon islands and Namonuito Atoll (synonym laniger Allen, 1890). Nomenclatorial issues notwithstanding, this arrangement follows in principle that of

“Hombron and Jacquinot, 1842” has long been the recognized authority for the name Pteropus insularis (e.g.

The description of Pteropus insularis by

Records of flying foxes from the northern Mortlocks are scanty, lacking in substantive detail, and confined to Losap Atoll; no records exist for Nama Island.

In the late 1980s, government officials on Weno, Chuuk Lagoon, reported bats present on Losap Atoll and said that a Losap islander was among several Mortlockese shipping bats to Weno for export to the Mariana Islands (

DWB saw no bats on Losap Atoll during a one-day visit that included 2–3 hrs each on Pis, Losap, and Lewel Islands in July 2004. Lewel, the largest island in the atoll, has extensive breadfruit-coconut forest typical of bat habitat elsewhere in the Mortlocks. It is used as a garden island by the people of Losap Island, but has no permanent settlement or resident families. He walked the length of Lewel through the center and returned via a shore route without seeing bats. None of the several Losap and Pis residents interviewed during his visit knew of bats occurring on the atoll.

DWB spent one week on nearby Nama Island without seeing any bats or encountering any resident islanders who had seen them. Mitaro Chosa (pers. comm.), deputy mayor of the island and age 58 in 2004, was firm in his conviction that bats had not occurred on Nama during his lifetime.

These few, and in some cases questionable, records together with the lack of sightings during this study suggest that flying foxes are absent from Nama Island, and are either recently extirpated or possibly still present in such small numbers as to be unknown to many islanders on Losap Atoll.

DWB observed small numbers of bats on all the islands in July 2004. The encounter rate on Namoluk Island averaged four per hour during six 45-minute walks in the least disturbed parts of the coconut-breadfruit forest on four different days. Overall, an estimate of 150–200 bats was made for the atoll. However, Maikawa Setile (pers. comm.), deputy mayor of Namoluk, claimed that bats were more abundant at certain times, especially when breadfruit was in season. He recalled seeing large numbers of bats in the settlement earlier in 2004, with as many as 50 in one tree.

There are few historical accounts of flying foxes in the southern Mortlocks. J. Nason (pers. comm.) reported “scores of fruit bats... possibly 100+” on Ettal Island, Ettal Atoll, during the late 1960s.

During field surveys in 2004, DWB found bats to be uncommon on Ettal Atoll and estimated 75–100 to be present. He saw only five or six bats flying in and out of several breadfruit trees in the village on Ettal Island at sunset on 30 and 31 July, and observed only one bat during several walks elsewhere on the island and none on three of the atoll’s smaller outlying islands. One resident stated that he occasionally saw as many as 20–30 bats together in breadfruit trees in the settlement.

DWB judged bats to be common on Lekinioch Island, Lukunor Atoll, in 2004. He counted 53 bats in flight over the central taro patch and adjacent forest during 30 minutes near sunset on 2 August. No other station counts were made and no bats were seen during daytime walks among breadfruit and coconut trees in the settlement. However, the less disturbed areas of the island where bats were more likely roosting were not visited. DWB was unable to visit other islands in the atoll in 2004, but many of the people interviewed on Lekinioch, as well as former Lukunor residents living on Pohnpei at the time, reported bats on Oneop and many of the smaller islands. An overall estimate of 300–400 bats was made for the atoll.

In 2012, DWB visited all of the islands in Lukunor Atoll except Lekinioch. Small numbers of bats were recorded on eight of the 17 islands visited, as follows: Oneop, 5 bats; Piafa, 1; Kurum, 1; Pienemon, 4; Fanamau, 1; Sapull, 6; Sopotiw, 2; and Fanafeo, 1. Seven bats were noted flying between Sapull and Sopotiw Islands. No colonies were found and no population estimate was made for the atoll.

Surveys on Satawan Atoll in 2004 indicated that bats were common and regularly encountered, with an estimated 400–500 present. The largest numbers of bats observed during the study were on this atoll, with the greatest concentrations seen on Satawan and Ta, the two largest and southernmost islands in the Mortlocks. The encounter rate on Ta was eight per hour during walking surveys totaling 2.2 hours through breadfruit and coconut forest. The maximum number of bats observed during station counts was 81 in 25 min at Ta airport at sunset on 4 April. The largest aggregation observed during this study was 27 on Satawan Island (see Roosting below). One to 10 bats (usually less than five) were encountered per visit on other islands in the atoll, including Weito in the south; Kuttu, Orin, Pike, Mariong, Apisson, Lemasul, and Alengarik in the northwest; and Faupuker, Pononlap, and Fatikat in the east. Numbers of bats noted on Ta in 2012 matched or exceeded those recorded in 2004, and included many flying to or from Satawan Island.

Pteropus phaeocephalus pelagicus characteristically roosted singly or in small, loose aggregations of 5–10 individuals, usually in the crowns of coconut and breadfruit trees in closed or nearly closed canopy forest outside of settlements. A maximum of 27 was seen together in the crowns of two adjacent coconut trees at the northern end of Satawan Island on 2 July 2004, with seven roosting along the rachis of a single palm frond and separated from each other by one or two body lengths. Bats were frequently observed hanging from tree branches and palm fronds, and occasionally clinging to the trunks of coconut trees a short distance below the crowns. Roosting bats were noted to occasionally stretch their wings and reposition themselves, or awake and relocate to another site. Some were seen crawling on the petiole bases of palm fronds and disappearing from view among the leaf axils.

Ripe breadfruit is apparently one of the most preferred food items of Pteropus phaeocephalus pelagicus. DWB saw bats active in breadfruit trees at night on all the atolls having bats, and resident islanders invariably mentioned the fruit of breadfruit at the top of their lists of foods eaten by bats. Other foods reported by islanders were banana (Musa sp.; fruit), coconut (parts eaten unknown), papaya (Carica papaya L.; fruit), Calophyllum inophyllum L. (fruit), Crataeva speciosa Volkens (fruit), Pandanus cf. tectorius Parkinson (fruit), and Ficus tinctoria G. Forster (fruit). The only observation of bats feeding was on Weito Island, Satawan Atoll, at sunset on 3 July 2004, when three or four bats repeatedly flew in and out of the dense foliage of a pandanus tree. One flew away with a segment of ripe fruit and another dropped a segment while flying over the beach.

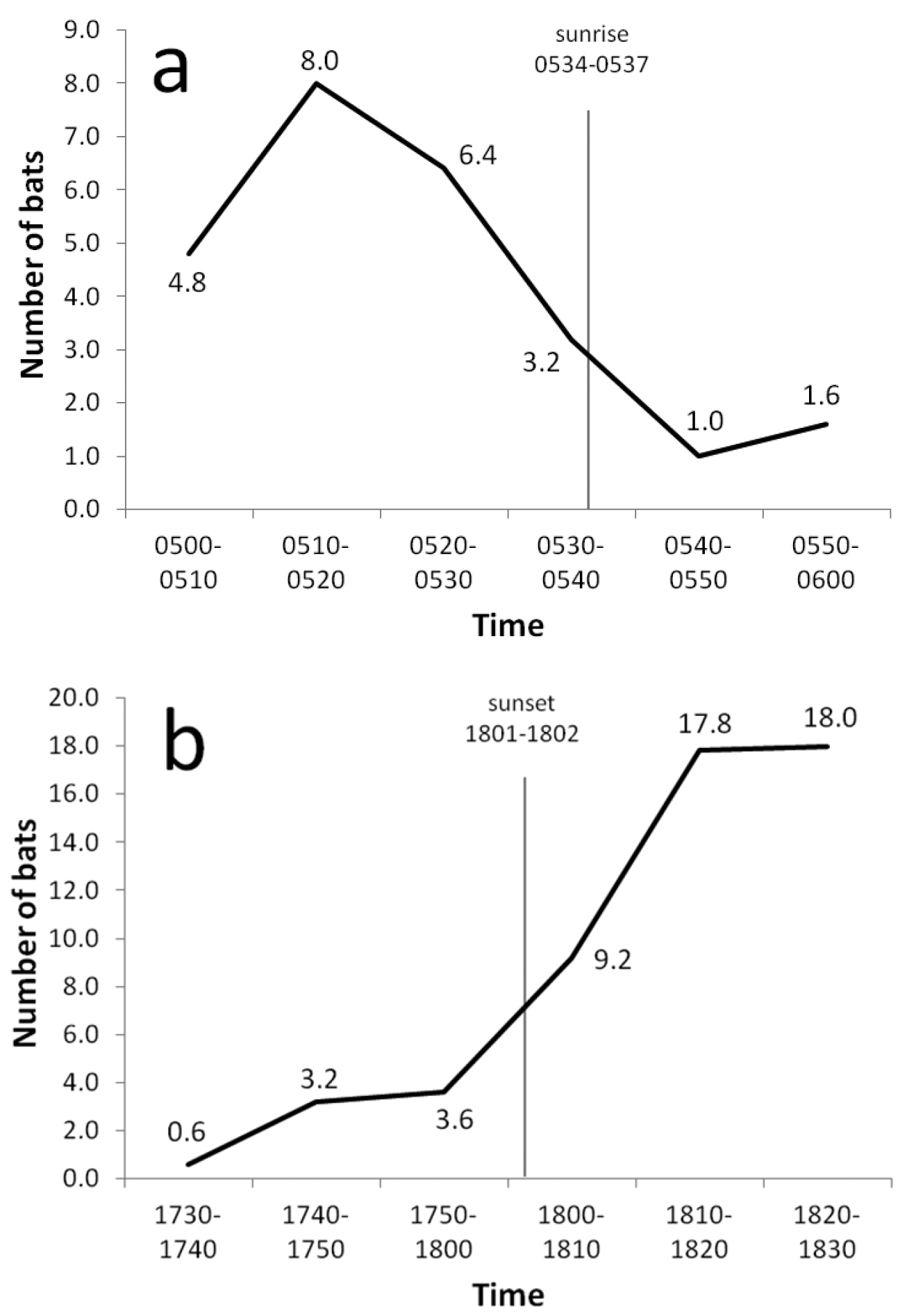

Flying foxes were observed flying at all hours, including midday, although some daytime activity was doubtless caused by the observer’s passage. Flight activity was greatest near sunset and sunrise (Figure 7) when bats moved between day roosts and foraging sites. Fewer bats were encountered at sunrise than at sunset, suggesting that some animals returned to roosts before daylight. The direction of evening flights probably was associated with the location of food resources, often ripe breadfruit according to local residents. During April and June 2004, with the exception of a few individuals settling in nearby trees, all bats observed during evening flights at the Ta airport station moved toward the western end of the island; in July and August, 19–40% of bats flew from west to east. Interisland flights within atolls occurred regularly near sunset, but none were recorded at other times (Table 5). No bats were seen flying between atolls.

Mean number of bats observed per 10-minute count period during (a) five early morning counts from 23 June–6 July 2004 and (b) five evening counts from 22 June–3 August 2004 at the airport on Ta Island, Satawan Atoll, Mortlock Islands.

Numbers of bats observed flying between islands during six sunset and three sunrise counts at six different stations on Satawan Atoll, Mortlock Islands, 24 June–3 July 2004.

| Stationa | Date | Time | Number of bats | Direction of flight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fatikat | 26 June | 1745–1815 | 0 | |

| 1 Fatikat | 27 June | 0515–0545 | 0 | |

| 2 Satawan (east end) | 2 July | 0500–0530 | 0 | |

| 2 Satawan (east end) | 2 July | 1730–1830 | 1 | Fatikat to Satawan |

| 2 Satawan (east end) | 3 July | 0430–0545 | 0 | |

| 3 Satawan (west end) | 1 July | 1725–1850 | 7 | Ta to Satawan |

| 4 Ta (east end) | 25 June | 1730–1830 | 0 | |

| 5 Ta (west end) | 24 June | 1715–1830 | 0 | |

| 6 Weito (east end) | 3 July | 1700–1835 | 8 | Weito to Ta |

a See Figure 1 for locations.

At least 50% of the bats observed on Namoluk Atoll in July 2004 appeared to be females with young. In some cases, young were evident only as a bulge beneath a female’s wing. Large volant young were occasionally seen in close proximity to or in body contact with their presumed mothers. Among five females collected on Namoluk Atoll on 21–22 July 2004, two contained single fetuses (crown-rump length 68 mm, mass 27 g, but with part of the brain case shot away; crown-rump length 42 mm) and a third had an immature male (forearm 78 mm, head-body length 110 mm) clinging to its ventral surface. Two females collected on Satawan Atoll in April 2003 each had a large young (head-body length 100, 100 mm; mass 62, 65 g) clinging to their ventral surface. Two adults were observed copulating in the crown of a coconut tree on Ta Island on 24 December 2002.

Our examinations and analyses of craniometric and pelage variation in the flying foxes of Chuuk State demonstrate minor but largely consistent morphological distinctions between flying foxes of the Mortlock Islands and those from the islands of Chuuk Lagoon and Namonuito Atoll. We regard these differences as indicating no more than subspecific distinction between these two regional groupings, which we refer to Pteropus pelagicus (Pteropus phaeocephalus pelagicus and Pteropus phaeocephalus insularis, respectively). A specimen from Namonuito Atoll, the enigmatic type series of Pteropus laniger, and a series of seized bats said to originate from Chuuk State, are all best referred to Pteropus phaeocephalus insularis. The closest relative of Pteropus pelagicus is the recently extinct Pteropus tokudae of Guam, which based on its consistently smaller size, shorter and narrower rostrum, darker coloration, and considerable geographic isolation from Pteropus pelagicus, is best regarded as a distinct species (cf.

The subspecific status of flying foxes in the northern Mortlocks remains unresolved. The nearest neighboring populations are comprised of Pteropus phaeocephalus insularis on the islands of Chuuk Lagoon 66 km to the northwest and Pteropus phaeocephalus pelagicus on Namoluk Atoll 110 km to the south. Both distances are perhaps within the flight capabilities of the species. However, based on its nearer distance and much larger land area that would support a larger bat population producing potentially more dispersing individuals, Chuuk Lagoon would appear to be a more likely source of animals colonizing Losap Atoll and Nama Island. Interisland movements of up to 119 km and corresponding genetic exchange have been reported in Pteropus mariannus in the Mariana Islands (

The entire population of Pteropus phaeocephalus pelagicus is probably currently restricted to the four atolls comprising the southern and central Mortlock Islands, which total 10.1 km2 in size. A few additional bats may be present on Losap Atoll in the northern Mortlocks, but it is unclear which subspecies these might represent. Our study provides the first population estimate for Pteropus phaeocephalus pelagicus, with approximately925–1, 200 bats present in 2004. About 75% of the population occurs on the two atolls with the largest land areas: Satawan and Lukunor. Resident islanders in the southern and central Mortlocks reported that bats were more common in the past, but that numbers appeared to have remained relatively stable in recent years. Residents also stated that bat abundance seems to fluctuate with the seasonal availability of food, especially breadfruit, but this impression likely comes from the bats’ strong attraction to villages during the peak fruiting season of breadfruit.

Some double-counting of flying foxes may have occurred during our survey due to movements of bats between atolls. However, this problem was probably minor because our primary survey period when all six island groups in the Mortlocks were visited was limited to a 6-week period from 22 June to 5 August 2004, thus reducing the likelihood of significant inter-atoll flights.

Recent data are lacking on the status of Pteropus phaeocephalus insularis. The main population in Chuuk Lagoon probably numbered in the mid-thousands in the early 1980s, but was reduced in abundance by commercialized hunting in the latter part of that decade (

Our survey efforts, including conversations with islanders, failed to confirm the presence of two other bat species in the Mortlock Islands, both of which are based on questionable early records.

Atoll-dwelling populations of Pteropus are of ecological interest because of their occurrence on islands with impoverished and often highly human-altered floras (see

Most species of Pteropus are seasonal breeders with births synchronized over a period of several months (

With a small population size and a geographic range comprised of many small low-lying islands totaling <12 km2, flying fox populations in the Mortlock Islands are highly vulnerable to environmental changes and certain human activities. The apparent depletion or possible extirpation of bats on Losap Atoll in the northern Mortlocks during the past 60 years underscores this vulnerability.

Sea level rise associated with climate change may represent the greatest long-term threat to Pteropus phaeocephalus pelagicus and other populations of atoll-dwelling Pteropus (

The negative impacts of severe cyclonic storms on Pteropus populations are well documented and occasionally include significant population declines (e.g.,

In 1976, Typhoon Pamela killed most of the tree crops (e.g., breadfruit, coconut, and banana trees) on the islands of Ettal, Namoluk, Kuttu, Oneop, Moch, and Nama (

Current model projections suggest that typhoon intensity will increase, but frequency may decrease, in the western Pacific as climate change progresses over the next century (

The extent that Mortlock bat populations have been affected by severe typhoons in the past is undocumented. However,

Centuries of human occupation have greatly altered the vegetation of the Mortlocks, but anthropogenic disturbance is now low despite the atoll’s high human population density. The coconut-breadfruit-pandanus forests where bats roost and feed are economically important to islanders, and they manage this resource sustainably. Cutting and clearing of the undergrowth occurs sporadically and is usually done on small, family-owned plots, but widespread cutting of forest does not occur. Additionally, a high emigration rate of Mortlockese to the larger islands of Micronesia and to overseas locations for better job opportunities (

Overhunting has contributed to declines in flying fox populations in many areas of the Indo-Pacific region (e.g.,

Like the vast majority of islanders from Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae states, Mortlockese almost universally disdain flying foxes as food. From the late 1960s to 1980, anthropological researchers noted that bats were not hunted or eaten on Ettal Island (

Once, long ago, the rat was envious of the bat’s wings. The rat asked the bat if he could borrow his wings for a short time just to have a brief experience of flying; he promised to return them soon. The bat allowed the rat to use his wings. But the rat lied and flew away with no intention of returning the wings. Now, what was rat is bat and the original bat is the rat.

Flying foxes may have been a part of the Mortlockese diet in the past, when reliance on local foods was greater and food supplies from Chuuk Lagoon and Pohnpei were not so readily available, and bats may still be utilized on occasion especially when other foods become scarce, such as after typhoons.

Potential predators of flying foxes in the Mortlocks include four non-native species: cats (Felis catus Linnaeus), rats (Rattus exulans (Peale) and Rattus rattus complex;

Pteropus pelagicus pelagicus

Mortlock Islands: Namoluk Island, Namoluk Atoll (4 skins and skulls and 2 fluid preserved adults, field numbers 12–17, plus two unnumbered fetuses and one unnumbered young, all COM collections); Satawan Island, Satawan Atoll (11 skins and 9 skulls, COM field numbers 1–11); “Mortlock Islands” (in fluid with skull extracted, BMNH 82.10.27.4 [holotype of phaeocephalus]).

Pteropus pelagicus insularis

Chuuk Lagoon islands and Namonuito Atoll: “Ruck” (skull, MNHN 1996-2112 (apparently originally A6770 fide

Pteropus tokudae

Guam (2 skins and skulls, AMNH 87117 [holotype of tokudae] and 87118, and 1 skull, AMNH 256558).

Pteropus cf. pelewensis

“Ruck” (skull, ZMB 5697); Pohnpei (skull, ZMB A4065).

We thank Phil Bruner (BYUH), Judy Chupasko and Terry McFadden (MCZ), Paula Jenkins, Richard Harbord, Roberto Portela Miguez, and Louise Tomsett (BMNH), Nancy Simmons, Eileen Westwig, and Jean Spence (AMNH), Peter Giere and Robert Asher (ZMB), Jacques Cuisin and Geraldine Veron (MNHN), Ned Gilmore (ANSP), and Darrin Lunde and Don Wilson (USNM) for loan of specimens, information on specimens in their care, for making collections available, or for other assistance during museum work. Mary Sears (Ernst Mayr Library, MCZ) kindly provided photocopies of library materials from special collections, including a scanned image of Pteropus phaeocephalus from the plate that accompanied the original description. Doug Kelly (COM) assembled the composite illustration in Figure 3. Lauren Helgen assisted with specimen photography and in preparing figures (Figures 2, 4, and 6). We also thank Bernhard Hausdorf, Ronald Janssen, and Katrin Schniebs for responding to queries concerning J. Kubary in the Mortlock Islands, Vladimir Loskot for his search of collection records in the Russian Academy of Sciences, and Mark Borthwick, James Nason, Charles Reafsnyder, Craig Severance, Mac Marshall, and Harley Manner for sharing their recollections on the status of bats in the Mortlocks. Paula Jenkins commented on portions of a preliminary draft of the manuscript.

We thank Al Gardner, Richard Hoffman, Tony Hutson, Paula Jenkins, Tim McCarthy, Storrs Olson, and Van Wallach for sharing their taxonomic views and knowledge of nomenclatural procedures, and Micaela Jemison for helpful suggestions. Paul Clark, R. Clouse, Doug Craig, A. Gardner, Claudette Lucand, S. Olson, Leslie Overstreet, and Geraldine Veron furnished information on the Voyage au Pole Sud.

We are especially grateful to the many people of the Mortlock Islands who assisted DWB in many different ways during his visits, particularly his island hosts, including Mitaro Josa on Nama, Maikawa Setile on Namoluk, Benjamin Johnna on Ettal, Richard Carlos on Satawan, Sander Mark on Kuttu, and Theodor Emuch on Moch. A special note of thanks is extended to Obed Mwarluk on Ta, who provided food and lodging during DWB’s many visits to Satawan Atoll and assisted with the logistics of travel and accommodations elsewhere in the Mortlocks.