(C) 2012 Marta Novo. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Conflict among data sources can be frequent in evolutionary biology, especially in cases where one character set poses limitations to resolution. Earthworm taxonomy, for example, remains a challenge because of the limited number of morphological characters taxonomically valuable. An explanation to this may be morphological convergence due to adaptation to a homogeneous habitat, resulting in high degrees of homoplasy. This sometimes impedes clear morphological diagnosis of species. Combination of morphology with molecular techniques has recently aided taxonomy in many groups difficult to delimit morphologically. Here we apply an integrative approach by combining morphological and molecular data, including also some ecological features, to describe a new earthworm species in the family Hormogastridae, Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n., collected in Sant Joan de les Abadesses (Girona, Spain). Its anatomical and morphological characters are discussed in relation to the most similar Hormogastridae species, which are not the closest species in a phylogenetic analysis of molecular data. Species delimitation using the GMYC method and genetic divergences with the closest species are also considered. The information supplied by the morphological and molecular sources is contradictory, and thus we discuss issues with species delimitation in other similar situations. Decisions should be based on a profound knowledge of the morphology of the studied group but results from molecular analyses should also be considered.

Species description, earthworm, morphological characters, molecular data, integrative taxonomy, homoplasy

Traditional methods for identifying earthworm species and their phylogenetic relationships (i.e., the study of their morpho-anatomical features) have been limited by high levels of homoplasy. The structural simplicity of earthworms, the low degree of variability and the overlap of diagnostic characters among species, the absence of a fossil record and their adaptation to life in the soil, are the principal factors responsible for the difficulties in recognizing species. DNA sequence data has however facilitated the distinction of closely related species and may be the solution to understanding the true level of biodiversity within morphologically-difficult groups, such as earthworms.

Some degree of controversy has arisen on how to describe and delimit species, but discrete morphological features remain the most used criterion. Others are in favour of molecular-based descriptions (e.g.,

Hormogastridae includes middle to large-sized earthworms, currently comprising 27-29 species and subspecies that are exclusively distributed in the western Mediterranean (

The taxonomy of this group, as in other earthworm families, has been based until now solely on morphological features. The first species described are Hormogaster redii Rosa, 1887 and Hormogaster pretiosa Michaelsen, 1899. Subsequently, other species were added to the group by different authors, including

During a collecting trip for the phylogenetic study of

We expect that this example, combining molecular and morphological data and including ecological features, goes beyond the specific interest of a new earthworm species description and could be applied to other groups with comparable taxonomic problems.

Material and methodsSpecimens were collected by hand and fixed in the field in ca. 96% EtOH, with subsequent alcohol changes. Once in the laboratory, specimens were preserved at -20 °C.

The studied material includes 22 specimens (five mature specimens, four semi-mature specimens with tubercula pubertatis and/or clitellum draft and 13 immatures or fragments) collected between Ripoll and Sant Joan de les Abadesses, road C26, km 210 in a little forest near the Ter river (42°13'30.0"N, 2°14'57.5"E). Mean annual temperature is 14.3 °C and mean annual precipitation is 724 mm, as indicated by the nearest weather station (in the airport of Girona, 55km away: http://www.aemet.es/es/serviciosclimaticos/datosclimatologicos/valoresclimatologicos?l=0367&k=cat)

Specimens have been deposited in the Oligochaete Cryo collection of the Departamento de Zoología y Antropología Física, Universidad Complutense de Madrid (DZAF, UCM), Spain.

Specimens of nearly all other hormogastrid species were examined for comparison (list of specimens in

Molecular data generation follow

We constructed networks with SplitsTree4 v.4.11.3 (

Paragenetypes of Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. with GenBank accession numbers. The holotype SAN 11 was not sequenced in order to preserve the specimen intact.

| Paragenetype | COI | 16S-tRNA |

|---|---|---|

| SAN1 | JN209553 | JN209358 |

| SAN2 | HQ621990 | HQ621884 |

| SAN3 | JN209557 | JN209360 |

| SAN4 | JN209555 | JN209361 |

| SAN7 | JN209556 | JN209362 |

| SAN8 | JN209559 | JN209363 |

| SAN9 | JN209558 | JN209364 |

| SAN10 | JN209554 | JN209359 |

Species represented in the network corresponding to the closest relatives of Hormogaster abbatissae, according to the phylogenetic study by Novo et al. (2011). More distantly related species appear in bold. GenBank accession numbers of the used sequences are shown for each gene.

Phylum Annelida Lamarck, 1802

Subphyllum Clitellata Michaelsen, 1919

Class Oligochaeta Grube, 1850

Order Haplotaxida Michaelsen, 1900

Family Hormogastridae Michaelsen, 1900

Genus Hormogaster Rosa, 1887

Type-species Hormogaster redii Rosa, 1887

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:6A388AC5-A2E4-4A32-9BA4-F0F1C5684EBE

http://species-id.net/wiki/Hormogaster_abbatissae

Holotype. Adult (Catalog # SAN11 DZAF, UCM), 42°13'30.0"N, 2°14'57.5"E, from a small patch of forest near the Ter river, road C26, Km 210, between Ripoll and Sant Joan de les Abadesses, Girona (Spain), leg. M. Novo, D. Díaz Cosín, R. Fernández, December 2006.

Paratypes. 21 specimens (Catalog # SAN1-10, 12-22 DZAF, UCM), same collecting data as holotype.

Other material examined. 16 Hormogaster species and several subspecies included in the study by

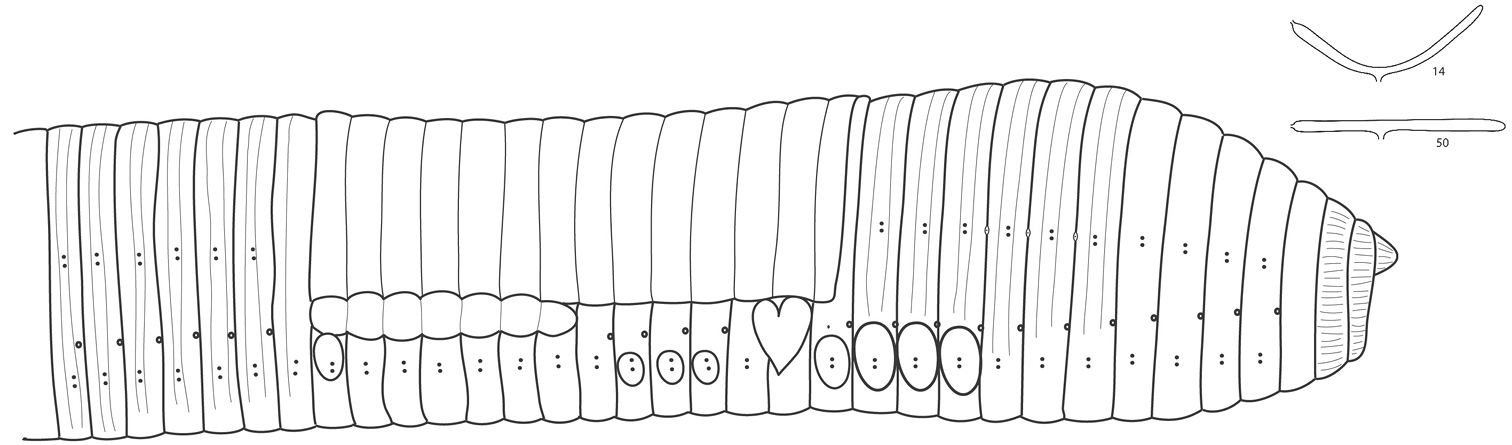

External morphology (Figure 1). Length of the mature specimens: 103-130 mm. Maximum diameter (pre-clitellar, clitellar, post-clitellar): 8, 11, 9 mm. Number of segments: 239-270. Weight (fixed specimens): 3.45-4.98 g.

Colour: Anterior pink in live animals, with darker clitellum and grey-bluish posterior (Supplementary Figure S.1B). Specimens are grey-bluish when preserved in ethanol, with beige clitellum (Supplementary Figure S.1D).

Prostomium proepilobic 1/3. Segments 1 and 2 showing longitudinal lines. Chaetae closely paired, quite lateral, visible along the body as two faint blue lines; intersetal ratio at segment 50, aa: 50, ab: 1.5, bc: 9, cd: 1, dd: 52. Nephridial pores in a row, between chaetae b and c. Spermathecal pores at intersegments 8/9, 9/10 and 10/11, at the level of chaetae cd.

Male pores opening near the 15/16 as elongated fissures at the level of ab, showing heart-shaped porophores of variable developmental degree that can cover practically all width of the segment 15 and ½ of 16 in mature specimens. Female pores in 14 more or less at the same level as the male ones.

Clitellum saddle-shaped extending over 14, 15–27. Tubercula pubertatis in (20) 21, 22–26, 27 appearing frequently as a continuous line in 21–27. Papillae with variable position, frequently situated at ab chaetae in segment 27, although more variable in other segments within the pre-clitellar and clitellar area.

Internal anatomy. Funnel-shaped and strongly thickened septa in 7/8, 8/9 and 9/10, also in 6/7 and 10/11, less thickened though. Last pair of hearts in 11. Three globular strongly muscular gizzards in 6, 7 and 8 of shining appearance. Not apparent Morren’s glands, although in transverse sections of the oesophagus at segments 10 to 14 some thickened blood vessels can be detected, but never the lamellae typically showed by this glands.

Lack of well-differentiated posterior gizzard, although the esophagus is a bit dilated at 15–16, but its wall is not especially muscular and its lumen does not exhibit a reinforcement similar to that in the anterior gizzards. In segments 17–25, 26, the gut shows folds in the wall of every segment, forming what has been called a stomach in some earthworms. Typhlosole begins in 20, 21 and presents 15 lamellae, being the two lateral ones very small that therefore could be unnoticed. Number of lamellae gradually decreases, showing three from segment 80 to 140–150, and one until 160–170 where the typhlosole ends. Therefore the last 70 to 100 segments lack the typhlosole.

Fraying testes and iridescent seminal funnels in 10 and 11. Two pairs of granular appearing seminal vesicles in 11 and 12 frequently showing black bodies. Ovaries and female funnels in 13; big ovarian receptacles in 14.

Three pairs of spermathecae in segments 8, 9 and 10 included into septa 8/9, 9/10 and 10/11 the ones in 8 being the smallest. Spermathecae with the appearance of flattened sacks, dish or flying saucer showing irregular borders inside the body wall under some of the muscular fascicles. They can be divided internally into interconnected lobes that in fact do not represent independent spermathecae but simple multicameral spermathecae that open to the exterior by a unique pore.

Anterior nephridial bladders V-shaped with widely open branches, being one of them shorter. They flatten towards the posterior section of the body, until the extent of showing appearance of an elongated sausage.

In some of the specimens, the sexual chaetae in 11 and 12 present well developed follicles that go into the body as a projection where various chaetae simultaneously appear.

Known only from its type locality.

Specimens were collected in a small forest patch dominated by Populus alba, Acer pseudoplatanus and Rosa canina, which develops in a slope at the edge of a meadow. The soil was covered with abundant leaf litter (Supplementary Figure S1. A), and it is characterized by 13.57% of coarse sand, 9.62% fine sand, 6.27% coarse silt, 32.37% fine silt, and 38.18% clay, constituting a clay loam soil, carbon (C): 4.48%, nitrogen (N): 1.32%, C/N: 3.39, pH: 7.09.

External morphology of Hormogaster abbatissae. An illustration of nephridial bladders in segments 14 and 50 is shown in the upper right corner.

The specific epithet derives from abbatissa, Latin for abbess, as the species is dedicated to the abbess Emma, the first Abbess head of the Monastery of Sant Joan de les Abadesses, founded in 885 AC by her father, the Count of Barcelona, Guifré el Pilós. The Monastery was run by nuns until the year 1, 017 when the female community was expelled, presumably for disorderly conduct, and replaced by monks.

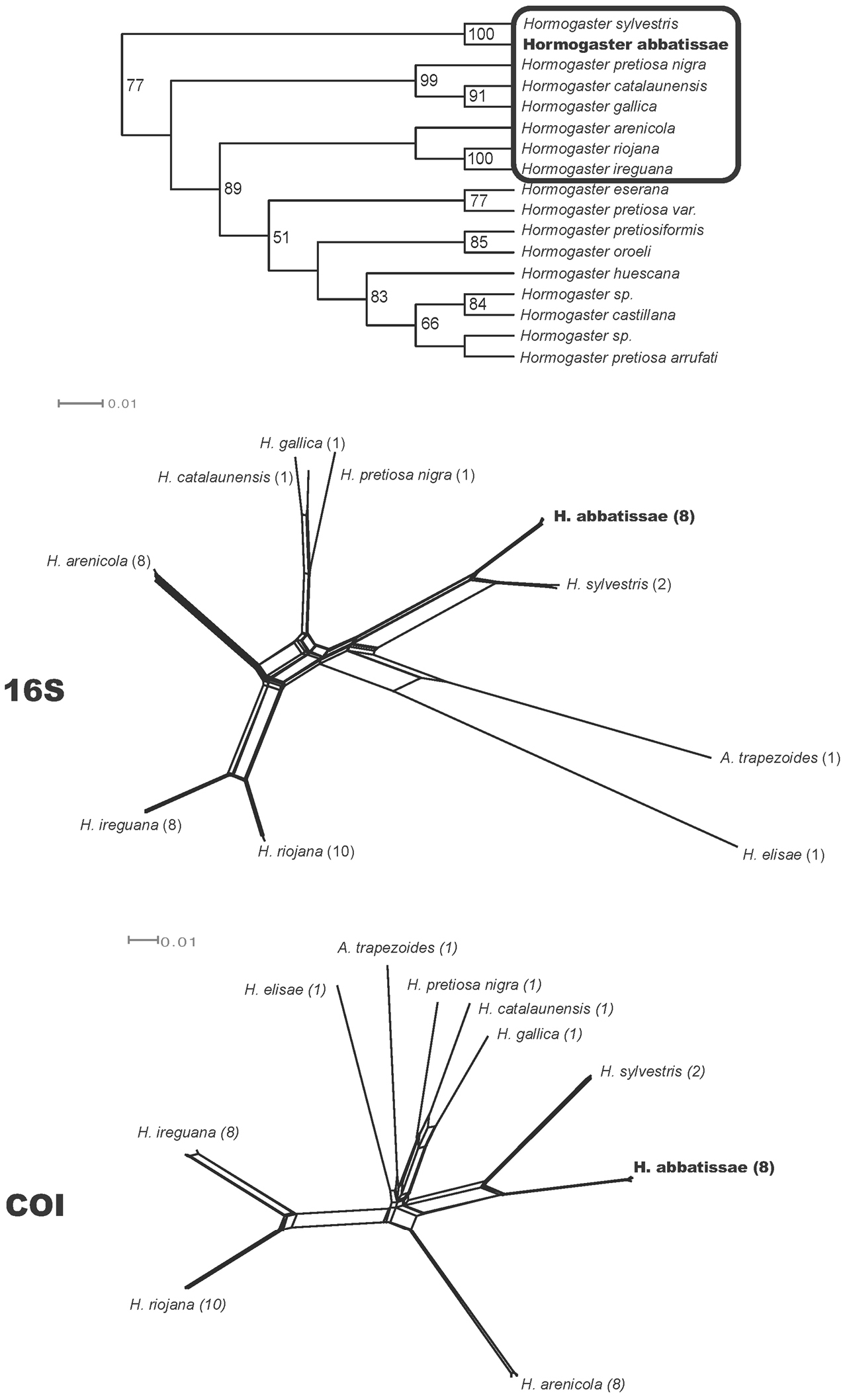

Sequences from COI (8 individuals), 16S-tRNA (8 ind.), histone H3 (4 ind.), histone H4 (4 ind.), 28S rRNA (2 ind.) and 18S rRNA (1 ind.) were analysed with additional hormogastrid species. Phylogenetic analyses of the molecular data shows robust support for the monophyly of Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n., which is the sister species of Hormogaster sylvestris Qiu & Bouché, 1998 (Figure 2), described in the nearby locality of Montmajor (Barcelona, Spain). This clade forms the sister group to almost all other Hormogaster species from the NE Iberian Peninsula (see

Uncorrected pairwise distances for 16S-tRNA and COI are shown in Table 3 for the sister species Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. and Hormogaster sylvestris and the morphologically-close Hormogaster riojana as well as its sister species Hormogaster ireguana Qiu & Bouché, 1998. Hormogaster elisae is included as a distant relative, even though it belongs to a possible new genus (see

The networks recovered by Splitstree4 for the COI and 16S genes including morphological and molecular closest species are shown in Figure 2.

GMYC analyses performed by

Soil characteristics in the localities where Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n., Hormogaster riojana and Hormogaster sylvestris occur are shown in Table 4. Differences in soil texture were detected: Hormogaster sylvestris and Hormogaster riojana inhabit Silt-loamy soils, whereas Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. inhabits Clay-loamy soils. Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. inhabits soils with a higher content in organic matter. Comparisons with the remaining species of the family were provided by

Top, part of the parsimony tree recovered by

Mean values of uncorrected pairwise differences in percentage obtained for 16S-tRNA (above the diagonal) and COI (below the diagonal, in bold) genes. Values of intraspecific differences are shown in the diagonal for the species that include more than one sequence type.

| Hormogaster abbatissae | Hormogaster sylvestris | Hormogaster riojana | Hormogaster ireguana | Hormogaster elisae | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormogaster abbatissae | 0.10/0.05 | 4.01 | 11.92 | 12.86 | 17.88 |

| Hormogaster sylvestris | 11.71 | 0.46/0.25 | 11.89 | 12.76 | 16.29 |

| Hormogaster riojana | 17.80 | 17.36 | 0/0.09 | 4.32 | 17.18 |

| Hormogaster ireguana | 16.11 | 18.58 | 9.53 | 0.33/0.03 | 17.72 |

| Hormogaster elisae | 18.42 | 19.68 | 18.52 | 19.48 | - |

Soil characteristics in the sampling localities of Hormogaster sylvestris (Montmajor MAJ), Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. (San Joan de les Abadesses, SAN) and Hormogaster riojana (Alesanco, ALE). CSand: coarse sand, FSand: fine sand, TSand: total sand, CSilt: coarse silt, FSilt: fine silt, Tsilt: total silt, Tex: textural class, SL: Silt loam, CL: Clay loam, C: percentage of carbon, N: percentage of nitrogen, C/N carbon/nitrogen relationship.

| CSand | FSand | TSand | CSilt | FSilt | TSilt | Clay | Tex | C | N | C/N | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAJ | 11.71 | 6.50 | 18.22 | 6.88 | 69.02 | 75.90 | 5.88 | SL | 2.98 | 0.83 | 3.6 | 7.39 |

| SAN | 13.57 | 9.62 | 23.18 | 6.27 | 32.37 | 38.64 | 38.18 | CL | 4.48 | 1.32 | 3.4 | 7.09 |

| ALE | 9.24 | 25.12 | 34.36 | 55.38 | 1.86 | 57.24 | 8.40 | SL | 1.63 | 0.30 | 5.33 | 7.33 |

Most species within the genus Hormogaster are very similar morphologically, with the clitellum, tubercula pubertatis, spermathecae and typhlosole, in addition to size or colour, being the key morphological characters traditionally used for species diagnosis. Table 5 includes a comparison of the characters of Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. with those of its closest congeners, showing a large degree of overlap in the distribution of these characters and their states. In this case we have a species that appears the closest morphologically, Hormogaster riojana, collected in Alesanco, a locality ca. 420 km from Sant Joan de les Abadesses, that can be distinguished by the body and clitellum colour, shape of the tubercula pubertatis and the number of spermathecae (although Hormogaster riojana specimens with three pairs of spermathecae have been reported by

The sister group of Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. is Hormogaster sylvestris (Figure 2), collected in Montmajor, 50 km away from Sant Joan de les Abadesses. These two species, closely related phylogenetically and biogeographically, are easilydistinguished by their tubercula pubertatis (generally starting in more anterior segments and finer in Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n), clitellum (shorter and saddle shaped in Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. and annular in Hormogaster sylvestris), spermathecae (three pairs in Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. and two pairs in Hormogaster sylvestris) and typhlosole (15 lamellae in Hormogaster abbatissae sp n. and 13 in Hormogaster sylvestris). To these characters we can add other more variable characters such as colour, length, weight and number of segments (Hormogaster sylvestris is longer, heavier and with a higher number of segments). Of all these characters, the presence of three pairs of spermathecae in Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. is the most conspicuous trait. It is therefore the combination of the morphological information and the phylogenetic position of the species, as derived from the molecular data, which aids in the global taxonomy of the group and serves to assess the degree of homoplasy in characters thought to be of taxonomic importance.

Some characters, such as the presence of Morren’s glands or the existence of a posterior gizzard, can be difficult to observe and of subjective interpretation. Morren’s glands seem to be absent because although an enrichment of blood vessels is detected in the oesophageal wall of some segments 10 – 14, the lamellae that define this organ were never observed. Likewise, the presence of a posterior gizzard is difficult to determine, as the gut thickens in segments 15 – 19 in the members of some species. However, in Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. there is neither strong musculature, nor the thickening and hard covering of the lumen as observed in the gizzards of earthworms.

Regarding the molecular characters,

After examining its morphology, phylogenetic placement and additional data such as GMYC and soil characteristics, it is evident that Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. constitutes a new hormogastrid taxon not phylogenetically related to those species that show closest morphological similarities. Morphological and molecular data supply different signals thus clashing in the case of Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. The question arising in this case is what should taxonomists do when different data sources provide conflict? The answer to this question is not straightforward. On the one hand, these animals can present a morphological stasis, as shown in Hormogaster elisae (

In this particular case, phylogeny is robust because it is based on a great amount of data, combining mitochondrial and nuclear genes (COI, 16S-tRNA, H3, H4, 28S, 18S) with different phylogenetic signal and including individuals representing most of the species in the family. Also we know that living conditions in the soil induce cryptic speciation processes in earthworms (

Regarding ecological factors, some important differences are detected for texture and organic matter among soils of Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n., Hormogaster sylvestris and Hormogaster riojana. However, it should be considered that a single locality is known per species and that the discovery of other populations may show a higher ecological range.

In summary, this study evidences the need of complementing the morphological data with molecular characters data in taxonomy, especially in groups with limited morphological characters and rampant convergence in their functional morphology, perhaps due to strong selective pressure due to habitat restriction. This study also proves that in case of rather small genetic divergence (within the range of uncertainty), morphology can be also helpful to conclude complementing molecular sources. We propose to establish the new species Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. Given the existence of species closely-related phylogenetically (Hormogaster sylvestris) and an unrelated but morphologically similar species (Hormogaster riojana), a more exhaustive sampling effort in NE Spain could provide new diversity to help evaluate this situation. As indicated by

Comparison of the morphological characters of Hormogaster abbatissae sp. n. with those in the morphologically closest species. N. segments: number of segments. N. typhlosole lamellae: number of typhlosole lamellae. Size, weight and number of segments are for adult specimens. For complete information of the rest of the species within Hormogastridae, see

| Hormogaster abbatissae | Hormogaster gallica | Hormogaster riojana | Hormogaster sylvestris | Hormogaster ireguana | |

| Colour | Grey-bluish | Dark brownish | Dark brownish | Colourless | Brownish-grey |

| Clitellum | 14, 15–27 (28)Saddle shaped, beige | (13) 14–28 (29, 30)*Saddle shaped | 13, 14, 17–27, 28Saddle shaped, dark | 15–28Annular | 13–27Annular |

| Tubercula pubertatis | (20) 21, 22–26, 27Fine band | (22, 23) 24 – 27Fine and short band | (20)21–27Fine band | 22–27Wide band | 19–26Linear band |

| Intersetal ratio | 50:1.5:9:1:52 | 69:1.3:8.8:1:66 | 55:1:13:1:65 | 50:2:10:1:50 | 120:1:20:1:100 |

| Length | 103–130 | 165–190 | 125–185 | 180–220 | 100 |

| N. segments | 239–270 | 250–433 | 243–278 | 350–420 | 223 |

| Weight (g) | 3.45–4.98 | 9.2–17 | 13.6–15.3 | ||

| Spermathecae(pores)Appearance | 8, 9, 10(8/9, 9/10, 10/11)Simple, Multicameral | 9, 10(9/10, 10/11)Multiple, sessile, in a ring | 9, 10(9/10, 10/11)Simple, Multicameral | 9, 10(9/10, 10/11)Simple, Multicameral | 8, 9, 10(8/9, 9/10, 10/11)Simple |

| N. typhlosole lamellae | 15(2 very small) | 13 | 15 | 13 | 19 |

| Morren gland | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Posterior gizzard | 15? 16 17?Very weak | 14–16?Weak | 15–16Weak | 16Weak | 14–15Weak |

| Other characters | Carinated anterior segments |

We are indebted to Fernando Pardos for the drawing of Figure 1 and to Gonzalo Giribet for his valuable comments on the manuscript. Subject Editor Rob Blakemore and three anonymous reviewers helped to improve a previous version. M.N. was supported by a Grant from the Fundación Caja Madrid and a Postdoctoral Fellowship from Spanish Government. R.F. was supported by a research contract from Spanish Government and a Postdoctoral Fellowship from Fundación Ramón Areces. This research was funded by project CGL2010-16032 from the Spanish Government.

Supplementary figure. (doi: 10.3897/zookeys.242.3996.app) File format: Adobe PDF file (pdf).

Explanation note: Sampling area of Hormogaster abbatissae (A), alive specimen (B), fixed specimens (D) and their spermathecae from one side of the body (C) numbered from anterior to posterior.

Copyright notice: This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.