(C) 2013 Robert K. Robbins. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

We describe Ministrymon janevicroy Glassberg, sp. n., from the United States (Texas). Its wing pattern closely resembles that of the widespread and well-known lycaenid, Ministrymon azia (Hewitson). The new species is distinguished by the structure of its male and female genitalia, by the patterning of the ground color on the basal half of the ventral hindwing surface, and by the color of its eyes. Adults of Ministrymon janevicroy in nature have olive green eyes in contrast to the dark brown/black eyes of Ministrymon azia. Ministrymon janevicroy occurs in dry deciduous forest and scrub from the United States (Texas) to Costa Rica (Guanacaste) with disjunct populations on Curaçao and Isla Margarita (Venezuela). In contrast, Ministrymon azia occurs from the United States to southern Brazil and Chile in both dry and wet lowland habitats. Nomenclaturally, we remove the name Electrostrymon grumus K. Johnson & Kroenlein, 1993, from the synonymy of Ministrymon azia (where it had been listed as a synonym of Ministrymon hernandezi Schwartz & K. Johnson, 1992). We accord priority to Angulopis hernandezi K. Johnson & Kroenlein, 1993 over Electrostrymon grumus K. Johnson & Kroenlein, 1993, syn. n., which currently is placed in Ziegleria K. Johnson, 1993. The English name Vicroy’s Ministreak is proposed for Ministrymon janevicroy. We update biological records of dispersal and caterpillar food plants, previously attributed to Ministrymon azia, in light of the new taxonomy.

Butterfly Eye Color, Curaçao, Isla Margarita, Ministrymon azia, Ministrymon janevicroy, Vicroy’s Ministreak

Ministrymon azia (Hewitson) (Fig. 1) is widely cited in faunal lists and occurs from the southern United States to southern Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina in virtually all lowland habitats, ranging from desert in coastal Peru and Chile to rainforest in the Amazon Basin (

The generic placement of Ministrymon azia is a bit of an historical puzzle.

We recently discovered that the traditional species concept of Ministrymon azia includes a cryptic species that occurs sympatrically and synchronically with Ministrymon azia from the United States (Texas) south into the Neotropics. The cryptic species was discovered in Texas and Mexico (

Standard methods were used to dissect genitalia and to prepare them for examination with an SEM (

We list genitalic dissections in Supplementary file 1 Ministrymon Genitalia Examined, images in nature in Supplementary file 2 Images of Live Butterflies, and data on forewing length and frequency of eye-color in Supplementary file 3 Ministrymon janevicroy Datasets.

Museum specimens cited in this study are deposited in the following collections – museum acronyms from

AMNH American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA

BMNH The Natural History Museum [formerly British Museum (Natural History) ], London, United Kingdom

DZUP Museu de Entomología Pe. Jesus Santiago Moure, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil

FSMC Florida Museum of Natural History (Allyn Museum/McGuire Center), University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA

MC Personal collection of Alfred Moser, Sao Leopoldo, RS, Brazil

TAMU Texas A & M University, College Station, USA

UCRC Entomology Research Museum, University of California, Riverside, California, USA

USNM National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:10ED3009-21F8-4B7C-B9B4-A93A5D867972

http://species-id.net/wiki/Ministrymon_janevicroy

Figs 1–4, 6–9Holotype: ♂ (Fig. 3). [hand written in black India Ink on white paper] July 12, 1969/Santa Ana Ref.[uge]/Hidalgo Co[unty]/Texas/J.B. Sullivan. [printed red label] Holotype/Ministrymon janevicroy/Glassberg. [printed green label] Genitalia No./2013: 10♂/R. K. Robbins. Deposited USNM. Paratypes (9♂, 4♀). Uvalde County. 1♂, Concan[, ] Tex[as]/7[July]-6-[19]36/W.D. Field. Hidalgo County. 8♂, same data as holotype. 1♀, June 12, 1976/Sullivan City/Hidalgo Co./Texas/J.B. Sullivan. 1♀ (Fig. 3), Pharr, Texas/20 April 1948/H.A. Freeman (via Nicolay collection). Kerr County. 2♀, Kerrville/Jun[e] 1917/Texas (via Barnes Collection). Paratypes have a blue printed paratype label and are deposited USNM. Five paratypes have been dissected and labeled as such (cf. supplementary file).

(excluded from the type series). Mexico: 33♂♂, 3♀♀. El Salvador: 1♀. Nicaragua: 4♂♂, 6♀♀. Costa Rica: 4♂♂, 1♀. Curaçao 2♂♂, 5♀♀ (FSMC). Venezuela: 2♀.

(excluded from the type series, specifics listed in a supplementary file).United States (Texas): 19, Mexico 10, Venezuela 1.

This species is named for my wife, Jane Vicroy Scott, whose love and patient forbearance have sustained me, and made me a more effective advocate for butterflies. Her tireless work in support of the North American Butterfly Association, especially with the National Butterfly Center in the Rio Grande Valley (less than 40km from the type locality of Ministrymon janevicroy), has helped make the world a little bit more friendly for butterflies and thus for people. The name is a non-latinized noun in apposition. I have proposed the English name Vicroy’s Ministreak for this species (

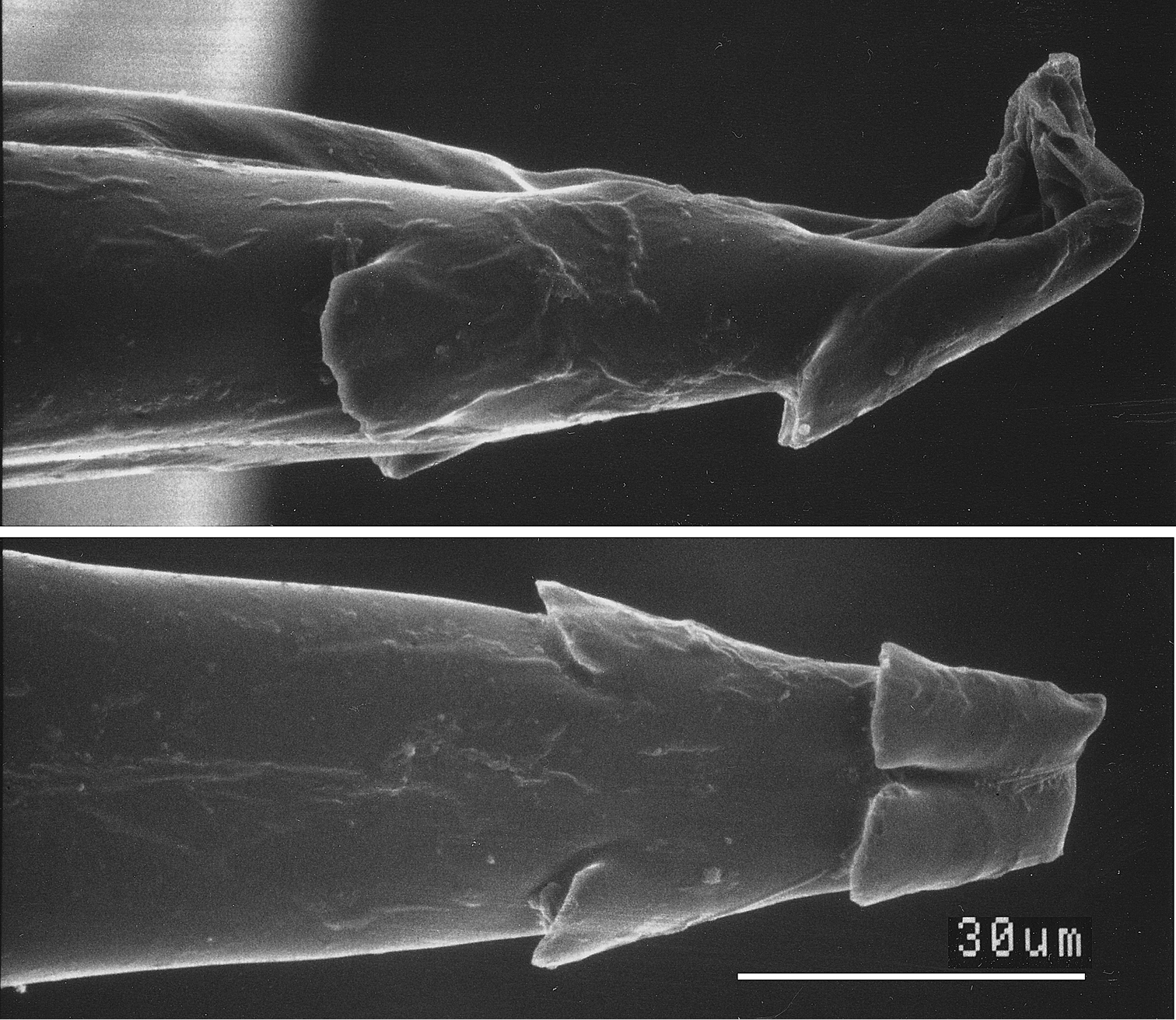

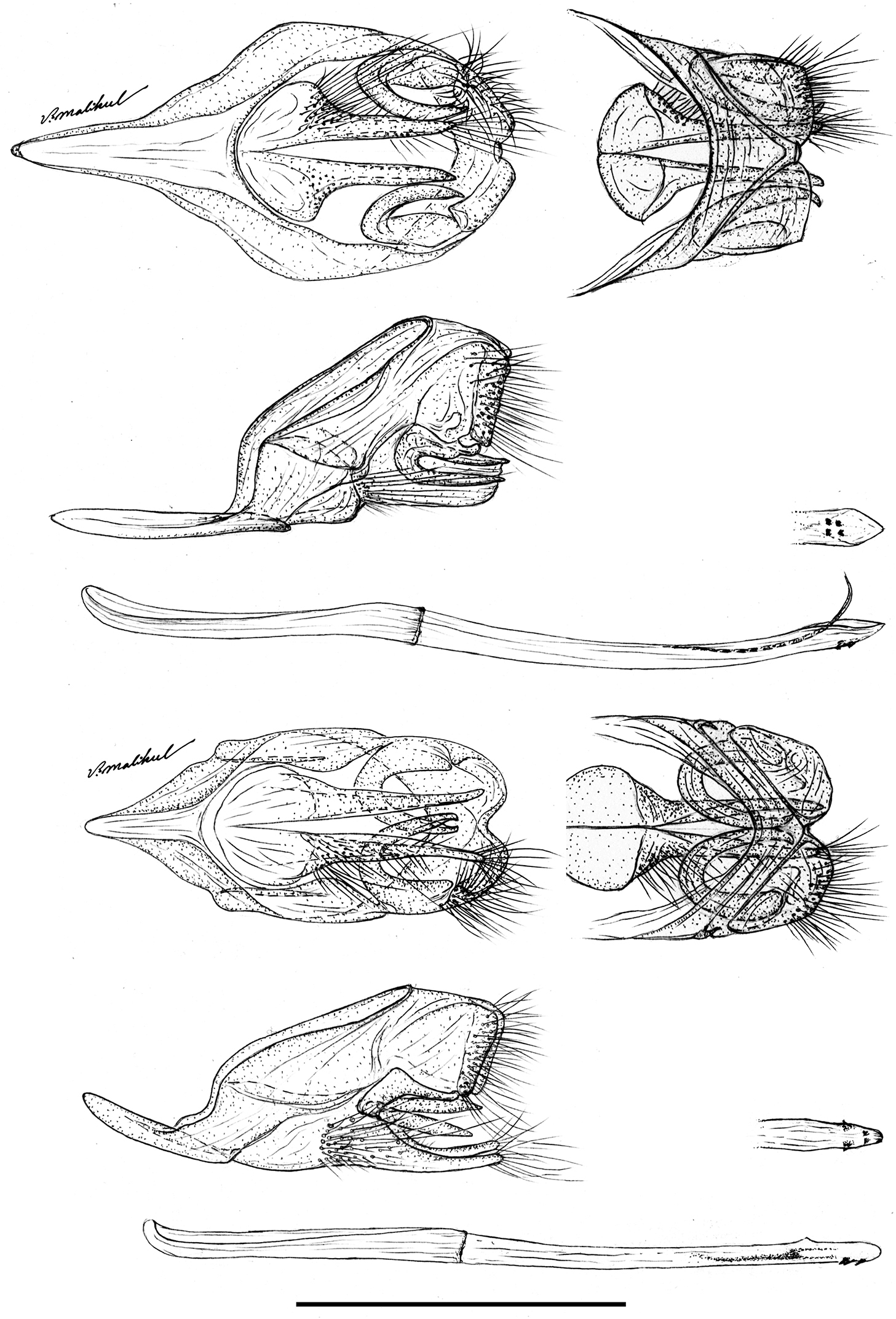

Ministrymon janevicroy is placed in Ministrymon because there are small erect teeth on the ventral surface of the penis near the distal end (Fig. 6).

Adults of Ministrymon janevicroy are differentiated from those of Ministrymon azia by (1) the male and female genitalia, (2) the ventral wing pattern, and (3) the color of the eyes.

The male genitalia of Ministrymon janevicroy (7 dissections, listed in supplementary information) differ consistently from those of Ministrymon azia (11 dissections), primarily by structures of the posterior penis (Fig. 6). The four—as illustrated—or five small erect teeth on the ventral surface of the penis tip of Ministrymon janevicroy are clustered anterior of the posterior penis tip while in Ministrymon azia two teeth are located near the posterior penis edge, well posterior of two other teeth. Inside the penis shaft, there is a single slender cornutus in Ministrymon janevicroy while the vesica on either side of the cornutus in Ministrymon azia is sclerotized. Depending upon the amount of sclerotization and the extent to which the vesica is everted, these sclerotizations may appear as a double prong (as in Fig. 6) or as a pair of lateral sclerotized triangular teeth. The shorter and squatter valvae in ventral aspect and the shallower and wider notch between the labides in dorsal aspect of Ministrymon janevicroy (illustrated in Fig. 6) represent individual variation and do not distinguish the species. The illustrated longer saccus of Ministrymon janevicroy (Fig. 6) may differentiate the species statistically, but this length in the study series was overlapping.

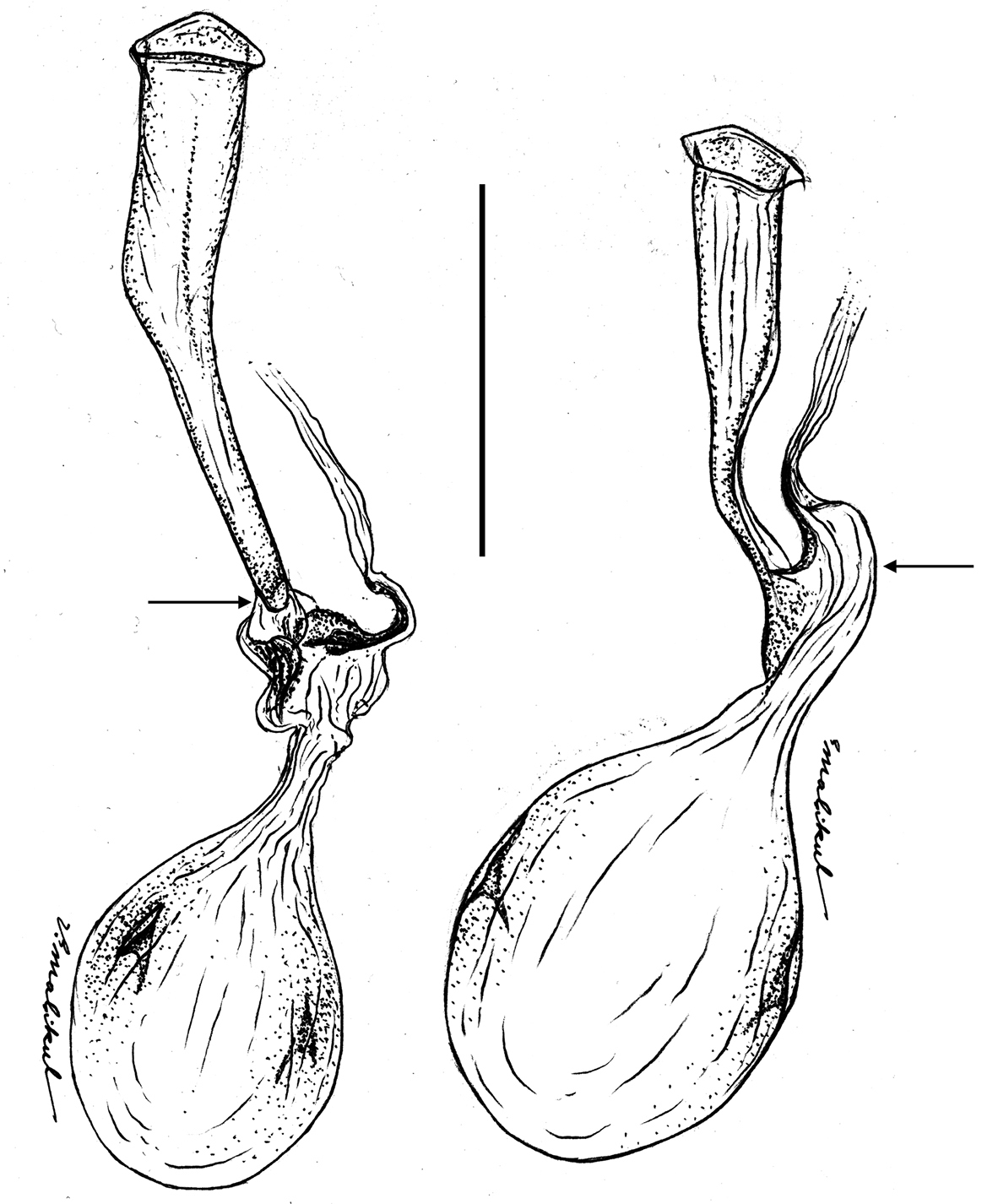

The female genitalia of Ministrymon janevicroy (6 dissections) differ substantially and consistently from those of Ministrymon azia (5 dissections). The female genitalia of Ministrymon janevicroy are distinguished from those of Ministrymon azia by a membranous “neck” just posterior of the cervix (arrow on the left of Fig. 7) and the lack of a well-formed posterior pouch from which the ductus seminalis arises (arrow on the right of Fig. 7). These differences are conspicuous and immediately distinguish the species. The illustrated ductus bursae of Ministrymon janevicroy is longer than that of Ministrymon azia (Fig. 7), but this difference represents individual variation.

Adults of Ministrymon janevicroy have olive green eyes in nature while those of Ministrymon azia have dark brown/black eyes (Fig. 1). The 30 images of adults in nature with a variegated “pebbly-textured” basal hindwing have olive green eyes, and the 44 images of those with a smooth-textured gray basal hindwing have dark brown/black eyes. In the museum study series, all Ministrymon azia adults had dark brown/black eyes while 9.5% of Ministrymon janevicroy adults had eyes as dark as those of Ministrymon azia (data in a supplementary file). The remaining adults of Ministrymon janevicroy had lighter eyes, ranging from yellow-brown to brown (this variation is shown in Fig. 3). It would appear that eye color darkens a variable amount post mortem in Ministrymon janevicroy. A survey of eye color in other Ministrymon species is presented in the discussion.

The wing venation of male and female Ministrymon janevicroy is illustrated (Fig. 8). In Ministrymon janevicroy forewing vein M2 arises closer to M1 than to M3 in both sexes, but is otherwise typical of the Eumaeini (

Ministrymon janevicroy occurs from southern Texas (there is also an image of an individual of this species from Big Bend National Park in western Texas, cf. supplementary information) to Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica and in South America on the islands of Curaçao and Margarita (Venezuela) (Fig. 4). It is a relatively common species in Central America, where it is as well represented in museum collections as Ministrymon azia. Ministrymon janevicroy appears to be absent from the Antilles (including Florida and the Lesser Antilles) and from South America, except for Curaçao and Venezuela’s Isla Margarita. It may also occur on Aruba, where Ministrymon azia was recorded (

Olive green eyes of Ministrymon janevicroy (left, Orizaba, Veracruz, Mexico) and the dark brown/black eyes of Ministrymon azia (Chavarrillo, Veracruz, Mexico).

Ministrymon janevicroy (left, close-up on bottom) with variegated “pebbly-textured” ground color and Ministrymon azia (right) with “smooth-textured” gray appearance. Both specimens from Managua, Nicaragua.

Male holotype (top) and female paratype of Ministrymon janevicroy. Eye color in the male appears to have darkened more post mortem than that of the female.

Distribution of Ministrymon janevicroy (hearts) based on museum specimens.

SEM of Ministrymon azia penis tip showing small erect teeth in lateral (top) and ventral aspect.

Male genitalia of Ministrymon janevicroy (top) and Ministrymon azia, posterior of butterfly at right, both from Yucatan, Mexico. Ventral aspect with penis removed (top left), lateral aspect with penis removed (left middle), lateral aspect of penis (bottom), penis tip in ventral aspect (right middle), and dorsal aspect of tegumen (top right). Scale 1 mm.

Bursa copulatrix of the female genitalia of Ministrymon janevicroy (left, Venezuela) and Ministrymon azia (Mexico) in dorso-lateral aspect, posterior of butterfly at top. Arrow on left points to the membranous “neck” of the anterior ductus bursae. Arrow on right points to the well-formed posterior pouch from which the ductus seminalis arises. Scale 1 mm.

Male (left, Yucatan, Mexico) and female (Santa Tecla, El Salvador) venation of Ministrymon janevicroy.

Male dorsal forewing scent patch showing dark brown wing scales covering tan-colored androconia.

Generic Placement and Identification. Ministrymon janevicroy is placed in Ministrymon because it possesses small erect teeth on the ventral surface of the penis near the distal end (Fig. 6). This synapomorphy for Ministrymon was proposed by

The hypothesis that Ministrymon janevicroy is reproductively isolated from the sympatric Ministrymon azia is well-supported. The male and female genitalic differences between the two are distinct and distinguishing (Figs 6–7). The variegated “pebbly-textured” ground color appearance of the basal part of the ventral hindwing (Fig. 2) is also distinguishing. The eye color difference is distinct and distinguishing in live individuals (Fig. 1) and in the majority of museum specimens. Ministrymon janevicroy is unrecorded from tropical wet lowland forest (>200 cm annual precipitation,

The substantive differences in the genitalic structures of Ministrymon azia and Ministrymon janevicroy (Figs 6–7) could be interpreted to mean that these two taxa are not closely related within Ministrymon. However, these species are sympatric in the same habitats, have very similar wing patterns, and the same androconial structures. If reproductive isolation between these species evolved by sexual selection acting on the genitalia (e.g.,

In the diagnosis and previous paragraphs, we distinguished Ministrymon janevicroy from Ministrymon azia because both share a similar ventral wing pattern. If Ministrymon janevicroy were more closely related to another described Ministrymon species, its ventral wing pattern would distinguish it immediately from that species.

Eye Color. The “hairiness” of adult eyes has been widely used in lycaenid taxonomy for more than a century (cf.

To provide context for the eye color difference between Ministrymon azia and Ministrymon janevicroy, we surveyed other Ministrymon species by recording eye color in museum specimens and in images of live adults. Ministrymon zilda (Hewitson) has a deep black eye color (an apparent autapomorphy), both in museum specimens and in live individuals. Ministrymon cleon (Fabricius) (cf.

This survey of Ministrymon adult eye colors leads to three conclusions. First, although similarity in wing pattern suggests that Ministrymon azia is the phylogenetic sister of Ministrymon janevicroy, adult eye color suggests that Ministrymon azia might be the phylogenetic sister of Ministrymon cleon. Clearly, a phylogenetic analysis of the genus is needed. Second, adult eye color is a useful taxonomic character in the field, but its use in the museum is more limited. In this case, all museum specimens in the “Ministrymon azia” complex with yellow-brown to brown eyes are Ministrymon janevicroy, but the converse is untrue. Third, the biological significance of adult eye color is yet unknown. There is no evident correlation with gender, habitat, or other biological traits.

Variation. While there was no discernible geographic variation in the morphology of Ministrymon janevicroy, three morphological aspects vary in single populations. First, when

Biogeography. A number of Central American eumaeine species occur in deciduous dry forest from the southern United States (Texas) or Mexico to Costa Rica (Guanacaste), but are unrecorded further south and east in Panama and northern Colombia. This species list includes Arawacus sito (Boisduval), Cyanophrys goodsoni (Clench), Cyanophrys miserabilis (Clench), Michaelus hecate (Godman & Salvin), Ministrymon clytie (W.H. Edwards), Rekoa zebina (Hewitson), Strymon alea (Godman & Salvin), Strymon bebrycia (Hewitson), and Ziegleria hoffmani (K. Johnson). Ministrymon janevicroy is now added to this list. Of these, only Strymon alea (Isla Margarita) and Ministrymon janevicroy are also recorded on islands just off the north coast of South America, but not from the dry continental forests of northern Venezuela and northern Colombia. It is possible that remnant populations of species that were once more widespread persist only on these islands, but alternately, the mainland Guajira peninsula of Colombia/Venezuela is yet poorly documented.

There is one female in the Ministrymon azia species group in the USNM from the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais that has the olive green eye color and variegated “pebbly-textured” wing pattern of Ministrymon janevicroy, but a different postmedian line on the ventral surface of the hindwing. Additionally, two males of the same species in MC are genitalically distinct from Ministrymon janevicroy (genitalic images sent to us by A. Moser). This species is a potential phylogenetic sister species of Ministrymon janevicroy. We are collaborating with Moser to find more specimens with the intention of describing it.

Nomenclature. Seven names have been applied to the species now called Ministrymon azia (

Faunal documentation. The Eumaeini fauna of the United States is well-documented, and most species described in the past 75 years have arguably been cryptic species that had been overlooked because of wing pattern similarity with known species. Specific examples are Satyrium caryaevorus (McDunnough), Satyrium kingi (Klots & Clench), Callophrys hesseli (Rawson & Ziegler), and Strymon solitario Grishin & Durden. To this list, we add Ministrymon janevicroy. In sharp contrast, slightly more than 20% of the Central and South American eumaeine fauna is undescribed (

Biology and updated taxonomy. The purpose of this section is to assess previously published biological information about Ministrymon azia in the context of the updated taxonomy. As noted in the introduction to this paper, Ministrymon azia occurs from the United States (Texas and Florida) to Chile in virtually all lowland habitats, ranging from desert in coastal Peru and Chile to rainforest in the Amazon Basin. The information in this paper is consistent with this statement, and we note that there are specimens of Ministrymon azia in the USNM from Hidalgo, Cameron, and Edwards County in Texas. Ministrymon janevicroy is restricted to dry deciduous forest and scrub, and its range is a subset of that of Ministrymon azia. These species appear to be sympatric wherever Ministrymon janevicroy occurs.

Ministrymon azia was the most common lycaenid migrating through Portachuelo Pass in northern Venezuela (

Published larval food plant records (all Fabaceae, one exception) for Ministrymon azia from areas where Ministrymon janevicroy does not occur are the plant genera Acacia Willd. in the United States (Florida) and Chile, Mimosa L. in Cuba, and Trinidad, and Leucaena Benth. in the United States (Florida) (

Reared museum specimens that we have seen have all been Ministrymon azia. We examined individuals of Ministrymon azia in the USNM that were reared from Leucaena in Florida (2♂, 2♀) and from Mimosa in Guerrero and Veracruz, Mexico (1♂, 1♀) and in Trinidad (2♀). In DZUP, there are reared specimens from Mimosa in Pernambuco and Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (2♂). Finally, we identified an adult female that was reared from Prosopis L. in Tarapacá, Chile, but deposition of this specimen is unknown.

Other caterpillar food plant records are currently ambiguous and may refer to Ministrymon azia or to Ministrymon janevicroy.

We thank Karie Darrow, Brian Harris, and Vichai Malikul for illustrative and technical assistance that greatly improved the quality of the paper. We are pleased to express our gratitude to Blanca Huertas and Dick Vane-Wright for sending images of the lectotype of Ministrymon azia and its genitalia; to Jackie Miller for arranging a loan of specimens that were a critical part of this paper; and to Nick Grishin for sending us copious quantities of relevant information. For sharing data, we thank Greg Ballmer, Richard Boscoe, Robert Busby, Mirna Casagrande, Mathew Cock, and Olaf Mielke. For pertinent nomenclatural and biogeographic discussion, we thank Gerardo Lamas. We are especially grateful to Alfred Moser for working with us on the taxonomy of Ministrymon azia in Brazil. For reading and commenting on the manuscript, we thank Robert Busby, Nick Grishin, Gerardo Lamas, Alfred Moser, Jane Vicroy Scott, Bo Sullivan, and an anonymous reviewer who made insightful suggestions.

List of genitalic dissections. (doi: 10.3897/zookeys.305.5081.app1) File format: Adobe PDF file (pdf).

Images of live butterflies examined. (doi: 10.3897/zookeys.305.5081.app2) File format: Adobe PDF file (pdf).

Data on forewing length and frequency of eye-color. (doi: 10.3897/zookeys.305.5081.app3) File format: Adobe PDF file (pdf).