(C) 2013 Astrid Eben. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Eben A, Espinosa de los Monteros A (2013) Tempo and mode of evolutionary radiation in Diabroticina beetles (genera Acalymma, Cerotoma, and Diabrotica). In: Jolivet P, Santiago-Blay J, Schmitt M (Eds) Research on Chrysomelidae 4. ZooKeys 332: 207–321. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.332.5220

Adaptive radiation is an aspect of evolutionary biology encompassing microevolution and macroevolution, for explaining the principles of lineage divergence. There are intrinsic as well as extrinsic factors that can be postulated to explain that adaptive radiation has taken place in specific lineages. The Diabroticina beetles are a prominent example of differential diversity that could be examined in detail to explain the diverse paradigms of adaptive radiation. Macroevolutionary analyses must present the differential diversity patterns in a chronological framework. The current study reviews the processes that shaped the differential diversity of some Diabroticina lineages (i.e. genera Acalymma, Cerotoma, and Diabrotica). These diversity patterns and the putative processes that produced them are discussed within a statistically reliable estimate of time. This was achieved by performing phylogenetic and coalescent analyses for 44 species of chrysomelid beetles. The data set encompassed a total of 2, 718 nucleotide positions from three mitochondrial and two nuclear loci. Pharmacophagy, host plant coevolution, competitive exclusion, and geomorphological complexity are discussed as putative factors that might have influenced the observed diversity patterns. The coalescent analysis concluded that the main radiation within Diabroticina beetles occurred between middle Oligocene and middle Miocene. Therefore, the radiation observed in these beetles is not recent (i.e. post-Panamanian uplift, 4 Mya). Only a few speciation events in the genus Diabrotica might be the result of the Pleistocene climatic oscillations.

Coalescence time, Diabroticina, host plants range, macroevolution, pharmacophagy, phylogeny

Why does a clade have more species than others within the same lineage? This is a common question in evolutionary biology that has been pondered for almost a century (Simson 1953,

Nevertheless, there are examples in which lineage radiation is not necessarily correlated with the evolution of phenotypic characters (

The family Chrysomelidae is the most species rich lineage of Coleoptera with nearly 40, 000 described species. All species feed on plants, and most of the species are specialists on a certain host (

The aim of the present study is to review the processes that shaped the speciation pattern of some lineages encompassed in Diabroticina beetles (i.e. genera Acalymma, Cerotoma, and Diabrotica), and to set those processes within a reliable time framework. To reach this objective we have performed phylogenetic and coalescent analyses based on DNA sequences from mitochondrial and nuclear loci. In a previous study we applied a molecular clock hypothesis on the evolutionary scenario for host-range expansion in Diabroticinas (

DNA sequences for 44 lineages of chrysomelid beetles were used for this study (Table 1). Most taxa were chosen because they occur sympatrically in Mexico that has been proposed as the putative centre of origin for Diabroticites. Twenty-four species were collected in the field and sequenced by us. The remaining taxa encompassed in the dataset were selected based on DNA sequences availability.

Diabroticina specimens used and GenBank accession numbers for the molecular markers.

| Taxa | COI | 12S rRNA | 16S rRNA | 28S rRNA | ITS2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acalymma albidovittatum Baly | AY242447 |

AY243713 |

|||

| Acalymma bivittatum (Fabricius) | AY242443 |

AY243709 |

|||

| Acalymma blandulum LeConte | AF278543 |

AF278558 |

|||

| Acalymma blomorum Munroe & Smith | AY533582 | AY533610 | AY533637 | AY243710 |

|

| Acalymma fairmairei (Fabricius) | AY533583 | AY533611 | AY533638 | AY243708 |

|

| Acalymma innubum (Fabricius) | AY533585 | AY533613 | AY533640 | ||

| Acalymma trivittatum Mannerheim | AY533584 | AY533612 | AY533639 | AY243711 |

|

| Acalymma vittatum (F.) | AY533586 | AY533614 | AY533641 | AY646317 |

AF278557 |

| Amphelasma cavum (Say) | AY533590 | AY533618 | AY533645 | ||

| Amphelasma nigrolineatum Jacoby | AY242488 |

AY243754 |

|||

| Amphelasma sexlineatum Jacoby | AY242489 |

AY243755 |

|||

| Cerotoma arcuata Olivier | AY242494 |

AY243760 |

|||

| Cerotoma atrofasciata Jacoby | AY533587 | AY533615 | AY533642 | ||

| Cerotoma fascialis Erickson | AY646323 |

||||

| Cerotoma ruficornis Olivier | AY646322 |

||||

| Cerotoma trifurcata (Forster) | AF395803 | ||||

| Diabrotica adelpha Harold | AF278552 |

AY243735 |

AF278567 |

||

| Diabrotica amecameca Krysan & Smith | AY533578 | AY533606 | AY533634 | ||

| Diabrotica balteata LeConte | AY533569 | AY533597 | AY533625 | AY243731 |

AF278568 |

| Diabrotica barberi Smith & Lawrence | AF278544 |

AF278559 | |||

| Diabrotica biannularis Harold | AY242466 |

AY243732 |

|||

| Diabrotica cristata (Harris) | AY533580 | AY533608 | AF278560 |

||

| Diabrotica decempunctata Latreille | AY242467 |

AY243733 |

|||

| Diabrotica dissimilis Jacoby | AY533577 | AY533605 | AY533633 | ||

| Diabrotica lemniscata LeConte | AF278546 |

AF278561 |

|||

| Diabrotica limitata (Sahlberg) | AY242481 |

AY243747 |

|||

| Diabrotica longicornis (Say) | AF278547 |

AF278562 |

|||

| Diabrotica nummularis Harold | AY533568 | AY533596 | AY533624 | ||

| Diabrotica porracea Harold | AY533571 | AY533599 | AY533627 | AY243737 |

AF278563 |

| Diabrotica scutellata Baly | AY533567 | AY533595 | AY533623 | ||

| Diabrotica sexmaculata Baly | AY533566 | AY533594 | AY533622 | ||

| Diabrotica speciosa Germar | AY533579 | AY533607 | AY533635 | AY646319 |

AF278569 |

| Diabrotica tibialis Baly | AY533576 | AY533604 | AY533632 | AY243746 |

|

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata duodecimnotata Harold | AY533572 | AY533600 | AY533628 | ||

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata howardi Barber | AY533573 | AY533601 | AY533629 | AY243738 |

AF278570 |

| Diabrotica undecimpunctata undecimpunctata Barber | AF278556 |

AF278571 |

|||

| Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte | AY533575 | AY533603 | AY533631 | AY243734 |

AF278564 |

| Diabrotica virgifera zeae Krysan & Smith | AY533574 | AY533602 | AY533630 | AF278565 | |

| Diabrotica viridula (Fabricius) | AY533570 | AY533598 | AY533626 | AY243748 |

AF278566 |

| Paratriarius curtisii Baly | AY533591 | AY533619 | |||

| Paratriarius subimpressa Jacoby | AY242461 |

AY243727 |

|||

| Trichobrotica nymphaea (Jacoby) | AY242440 |

AY243706 |

|||

| Trichobrotica sexplagiata Jacoby | AY533581 | AY533509 | AY533636 | ||

| Schematiza flavofasciata Guér | AY515035 |

AY507265 |

EF197976 | AY243786 |

AY514312 |

^:

bold:

°:

*:

+:

Three mitochondrial-genome regions (i.e. COI, 12S, and 16S) were sequenced to provide the adequate level of variability for reconstructing the phylogeny of this group. To complement the molecular dataset we downloaded supplementary data available in GenBank. This database provided us with two additional nuclear fragments (i.e. 28S and ITS2) and 20 extra Diabroticina species. The concatenated matrix, therefore, included sequences from five loci (three mitochondrial, and two nuclear), encompassing 44 taxa and 2, 718 nucleotide positions. Sequences for the 28S and complementary sequences for the cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) gene were taken from studies by

A small amount of tissue (i.e. 2 or 3 legs) was ground in Chelex 5% (w/v solution) for total genomic DNA extraction following the method suggested by

The phylogenetic hypothesis was reconstructed using Bayesian inference (BI). We used an Akaike Information Criterion (

Molecular markers best-fit evolutionary model, model parameters, and mean likelihood for trees inferred from Bayesian analyses.

| Maker | Model | Nucleotide frequency | Γ | Rate matrix | p-inv | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12S rRNA | TPM1uf + Γ | 0.380, 0.050, 0.117, 0.453 | 0.477 | 1.00, 5.29, 1.76, 1.76, 5.29, 1.00 | -2158.86 | |

| 16S rRNA | TVM + Γ | 0.409, 0.161, 0.080, 0.350 | 0.245 | 0.94, 4.25, 3.70, 0.83, 4.25, 1.00 | -2622.66 | |

| 28S rRNA | TPM2 + I | 0.250, 0.250, 0.250, 0.250 | 2.50, 9.48, 2.50, 1.00, 9.48, 1.00 | 0.759 | -2001.79 | |

| COI | GTR + Γ + I | 0.341, 0.133, 0.104, 0.422 | 0.384 | 0.80, 6.38, 2.05, 0.92, 17.7, 1.00 | 0.416 | -7899.90 |

| ITS2 | TPM1uf + Γ | 0.299, 0.180, 0.210, 0.312 | 0.411 | 1.00, 3.86, 1.64, 1.64, 3.86, 1.00 | -1891.23 | |

| Total evidence | GTR + Γ + I | 0.313, 0.157, 0.171, 0.359 | 0.625 | 1.32, 6.07, 4.10, 1.02, 10.2, 1.00 | 0.535 | -17525.05 |

lnL HM = harmonic mean of the normal logarithm for the tree likelihood score;

nr = not relevant in the best-fit model.

Times for potential isolation events within the Diabroticina beetles' phylogeny were calculated using the software BEAST v 1.7.5. (

Finally, we compared the rate and timing of diversification events among the major lineages of Diabroticina. The average time between nodes was used as a straightforward measurement of speciation time. It was obtained directly from the chronogram inferred with BEAST. We also calculated the D and S indexes that describe diversification rate (

The topologies of the best-scoring trees obtained for the individual partitions were congruent with the concatenated tree, with most nodes having good support (Figure 1). The Bayes factor indicated that the BI tree obtained with the data partitioned by DNA region was more informative (2ln = 7.48), although this difference was not necessarily significant (

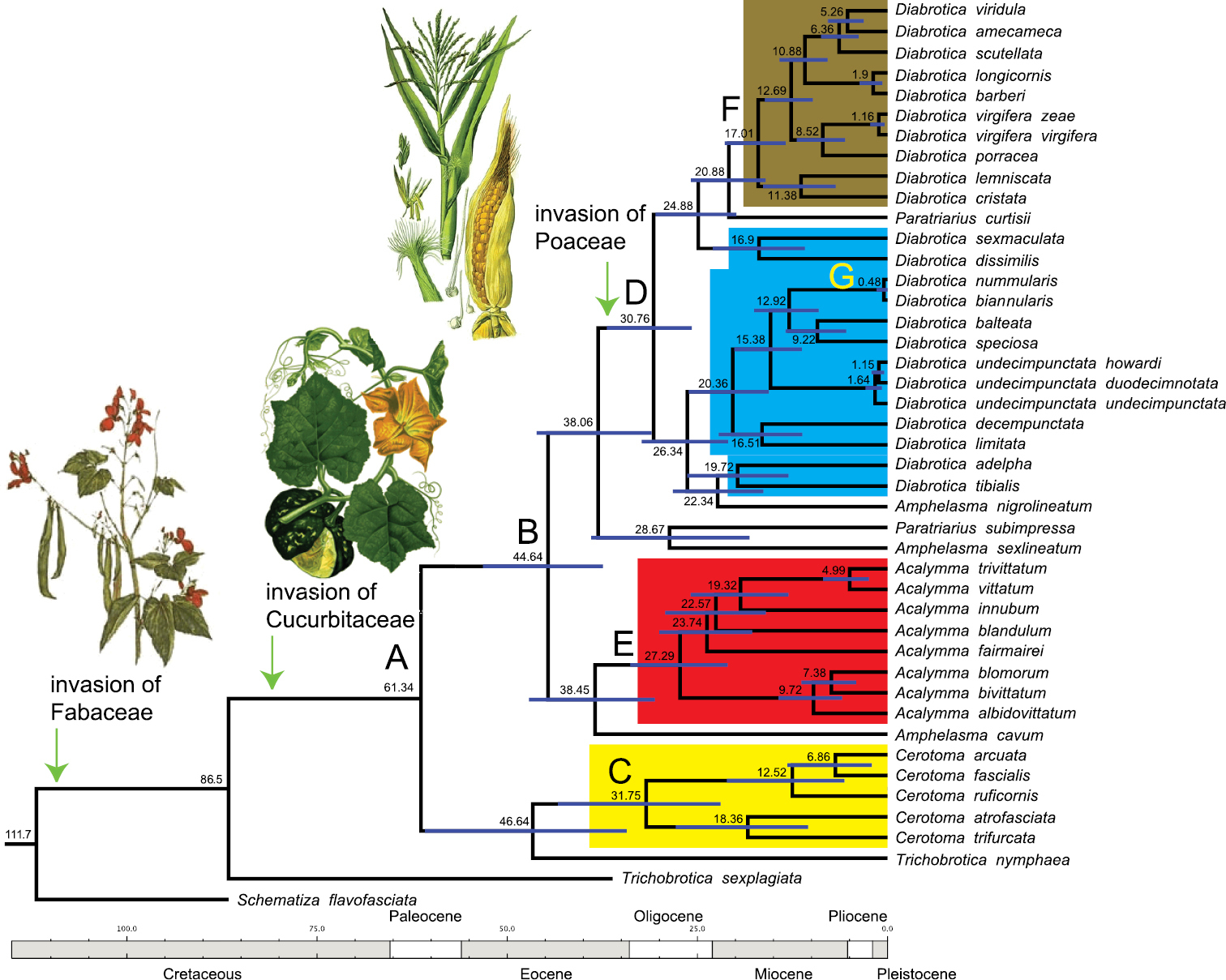

Phylogenetic tree recovered from Bayesian inference showing posterior provability values at the nodes. The genera Acalymma and Cerotoma are recovered as monophyletic lineages. Diabrotica, however, is paraphyletic unless some species of Amphelasma and Paratriarius are renamed as Diabrotica. The general evolutionary scenario for changes in diet spectrum is mapped in the phylogeny.

In the strict sense, the proposal for subdividing the Diabrotica species into smaller groups (i.e. virgiferaandfucata) was not supported in our study (Figure 1). Among the strongly supported relationships for Diabrotica sensu lato are the following: a) Diabrotica sensu lato was found to be monophyletic (PP = 1.0) and sister to the Amphelasma cavum-Acalymma spp. clade; b) Diabrotica sensu lato is split into three distinct monophyletic clades; c) all the species belonging to the so-called virgifera group are encompassed in Clade I in a well supported apical clade (PP = 1.0); d) in spite of that, the virgifera group is not supported as monophyletic group, since Paratriarius curtisii is included within this major clade; e) in Clade I, sister to the virgifera species is a monophyletic clade form by two fucata beetles (i.e. Diabrotica dissimilis and Diabrotica sexmaculata); f) the heterogeneity and instability of Clade I is demonstrated by the low support scored by BI (PP = 0.84); g) with moderate support (PP = 0.92) Clade II encompasses most of the species usually placed within the so-called fucata group (Diabrotica adelpha and Diabrotica tibialis, nonetheless, are found to be more closely related to Amphelasma nigrolineatum than to the remaining fucata species); h) at the base Diabrotica sensu lato, and sister to clades I-II, we recovered a highly supported (PP = 1.0) monophyletic clade form by Amphelasma sexlineatum and Paratriarius subimpressa. The polyphyly of the fucata group has been acknowledged before. Fucata was created as a convenience group for hosting a large number of highly variable species that did not fit into the virgifera or signifera group. Notwithstanding, the fucata and virgifera group could be easily rescued. Small adjustments, such as renaming Paratriarius to Diabrotica, and reassigning species from fucata into virgifera, would reconcile the observed phylogenetic pattern with the traditional taxonomy.

The other two genera survey within our analysis showedphylogenetic patterns more consistent with the taxonomic schemes. All the species of Acalymma form a strongly supported monophyletic clade (PP = 1.0). The Acalymma clade is divided in two monophyletic groups: one presents a strong interrelationship between Acalymma bivittatum-Acalymma blomorum, and Acalymma albidovittatum; whereas the other showed the next cladistic structure ((Acalymma blandulum, Acalymma fairmairei), (Acalymma trivittatum, Acalymma vittatum), Acalymma innubum). The genus Cerotoma is also monophyletic (PP = 0.97), and forms a sister genus to the Phyllecthrites species Trichobrotica nymphaea. This clade, formed by Cerotoma spp.-Trichobrotica nymphaea, is the most basal monophyletic group, and is the sister group of the “Acalymma-Diabrotica” clade (Figure 1).

The comparison of all coalescence analyses revealed high convergence among the inferred parameters, and ESSs were larger than 200 for all of them. Analyses of divergence time estimation using the calibration method resulted in very similar divergence estimates, for both the concatenated (Figure 2, Table 3) and the individual matrices (not shown; but available upon request). Likewise, the BEAST analyses based on the concatenateddataset, using the coalescent method assuming constant population size, exponential growth or logistic growth yielded similar time estimates for the different nodes of major Diabroticina clades. These results can thus be considered as robust (Figure 2, Table 3).

Chronogram inferred from a coalescence analysis. The blue lines at the nodes indicate the 95% confidence range for the estimated split times. Letters A to G pinpoint at key nodes in the evolutionary history of Diabroticina beetles (see Table 3 for further detail). The evolutionary scenario for the acquisition of main plant hosts is presented.

Chronology for key events during the evolutionary history of Diabroticina beetles.

| Node |

Event | Time Inferred | 95% confidence limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Split between Cerotomites / Diabroticites | 61.34 Mya | 54.92 – 67.76 Mya |

| B | Split between Diabrotica and Acalymma | 44.64 Mya | 37.41 – 53.17 Mya |

| C | Basal radiation within Cerotomites | 31.75 Mya | 21.96 – 43.34 Mya |

| D | Basal radiation within Diabrotica | 30.76 Mya | 25.76 – 36.88 Mya |

| E | Basal radiation within Acalymma | 27.29 Mya | 21.02 – 33.82 Mya |

| F | Basal radiation within vigifera group | 17.01 Mya | 13.41 – 21.10 Mya |

| G | most recent speciation event | 0.48 Mya | 0.01 – 1.45 Mya |

* as presented in Figure 2.

The mean value for divergence times indicated that the split between Cerotomites and the other Diabroticina subtribes occurred at ca. 60 Mya (95% confidence limits 55 - 68 Mya; Figure 2, node A). The split of the common ancestor of Acalymma and Diabrotica sensu lato was dated at ca. 45 Mya (95% confidence limits 37–53 Mya; Figure 2, node B). The important radiation events within the genera Cerotoma, Diabrotica, and Acalymma, began almost simultaneously; our estimates place these events at ca. 32, 31, and 27 Mya respectively (Figure 2, nodes C, D, and E). Another meaningful evolutionary episode in the history of the genus Diabrotica took place around 17 Mya. During that time, a reduction in the diet breadth of Diabroticina took place, resulting in a secondary specialization on host plants, switching from the polyphagous fucata to the oligophagous virgifera group (node F). Several speciation events were dated during the Pleistocene; being the most recent, the divergence between Diabrotica nummularis and Diabrotica biannularis that occurred ca. 500 000 years in the past (node G).

Based on the coalescent analysis we deduced that the main radiation within Diabroticina beetles occurred between middle Oligocene and middle Miocene (Figure 2). Cerotoma shows the slowest radiation rate with an average time between nodes of 13 My (Table 4). Acalymma has an intermediate radiation rate. This genus underwent on average one evolutionary splitting event almost every 7 My. Finally, Diabrotica sensu lato is the most specious clade; consequently, this group presents the highest radiation rate. The average time between internodes is 5 My. If we compare the number of lineages through time Cerotoma and Diabrotica sensu lato show a relatively constant increment in diversity. Acalymma instead, displays a fast increment in diversity between 27 and 19 My in the past, followed by a 10 My stasis period, and then new radiation events during the last 9 My.

Comparativerate and timing of speciation among Diabroticinas.

| Lineage | average time | S |

D |

γ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerotoma | 13.29 My | 0.034 | 0.057 | -0.273 |

| Acalymma | 7.62 My | 0.046 | 0.111 | -1.252 |

| Diabrotica sensu lato | 5.02 My | 0.068 | 0.154 | -1.510 |

| Clade I | 4.63 My | 0.071 | 0.152 | -0.992 |

| Clade II | 5.33 My | 0.062 | 0.187 | -0.818 |

a

b

Diversity patterns change across geography, geological time, and phylogenetic level. Key characters (e.g. flight ability, host specialization, pharmacophagy, etc.) are the central concept of the adaptationist approach that explains how lineages can radiate through those different levels. Species or lineages move into “unoccupied” or new adaptive zones, and thanks to those key characters the lineage goes through a process in which the rate of speciation depends on characteristics of that zone. If we analyze such an adaptationist approach to explain biodiversity based on its theoretical principles we might conclude the following: a) lineages radiate and adapt to different life strategies; b) those strategies are what we call “adaptive zones”; c) the main evolutionary force that mediates speciation (and extinction) rates is Natural Selection; d) this evolutionary force interacts with the fore mentioned key characters, resulting in further lineage adaptation and differentiation. Key characters are usually considered as intrinsic features of the lineage. Nonetheless, speciation rate is regulated by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Next we discuss a series of “key features” that may be responsible for modelling the biodiversity patterns observed in Diabroticina beetles.

Most wild species of Cucurbitaceae contain bitter, toxic secondary compounds known as cucurbitacins. These tetracyclic triterpenoids are synthesized from mevalonic acid. Cucurbitacins are the bitterest natural molecules known and protect the plants against many herbivores (

To gain access to the compounds, adapted beetles have developed curious behaviours. Morchete (Cucurbita okeechobeensis martinezii) leaves frequently show a semicircular cut along their edges. Field observations have demonstrated that a coccinellid beetle (Epilachna tridecimlineata) is responsible for this damage. This vein cutting behaviour impedes the coagulation of sticky phloem sap around the insect’s mouthparts. In continuation, the insect starts to feed on the tissues inside the circle. Once the trench is finished Diabroticina beetles begin to feed alongside the coccinellid from the tissue inside the semicircle (

Although the hypothesis of sequestering cucurbitacins for the insect’s protection is very appealing, there is data suggesting that Diabroticinas do not receive any fitness benefit from this behavior. On the contrary, some experiments have shown that the metabolic costs are high. For instance, the larvae fed on cucurbitacin containing diet have a lower growth rate than those fed on a cucurbitacin free diet (

So far, the available evidence for an advantage of pharmacophagy is inconsistent. More observations and experiments are essential to shed light on the role of pharmacophagy in the evolutionary fate of these beetles.

A lineage that occupies heterogeneous environments (e.g. geographical, ecological, climate, host species) might speciate more rapidly than others that inhabit homogeneous environments. When such is the case, the difference between closely related lineages showing disparate diversities is not due to the expression of key adaptation. It is just the consequence of exploiting environments of different complexity (

Host plant selection depends on the insect’s perception of the rate between stimulant and deterrent compounds in the plants. In the genus Chrysolina, host changes are preceded by exploring other closely related plant species (

One more process that may have favored the rapid radiation within Diabroticina is the result of ecological interactions with closely related lineages. Taxa that diversify to a large extent during their evolutionary history may fill available ecological space, pushing less fit individuals towards alternative adaptive zones leading to subsequent ecological diversification within subclades. Several evidences have supported such evolutionary pathways. It has been documented that strong competition occurs among the population members of some genera of lizards. In the absence of other sympatric species such competition, apparently, is responsible for the members of these taxa to experience ecological release and niche shifts (

In Mexico, Diabroticina beetles are rarely found feeding on cucurbit leaves (either wild or cultivated;

An untested hypothesis states that males may be searching for food sources rich in cucurbitacins, because these secondary compounds are transferred to the females within the spermatophors (

Differential selection (natural or sexual) intensities are the causal agent for variable rates of evolution and speciation (

One of the primary determinants of speciation rate is extrinsic, in that it largely interlocks processes external to the lineages that are differentiating. Spatial and long-term temporal variation in geological complexity influences the rate at which populations become isolated and therefore differentiated. Since the evolutionary synthesis, geographic isolation has been regarded as a main factor in promoting taxonomic differentiation within most terrestrial lineages (

Mesoamerica, the putative center of origin for Diabroticina beetles, is one of the most complex biogeographical areas in the world (

The identification of biogeographic breaks needs to be considered in a temporal framework, which allows comprehension of some of the present day diversity patterns for Diabroticina beetles. Temporal consideration in biogeographic analyses has been neglected in historical biogeography (

The use of divergence times has been severely criticized due to the presence of different rates of evolution in different taxonomic groups or even in individual genes (

While the origin of Diabroticinas could be set sometime during the Cretaceous (Figure 2), our data suggest that the diversification of the Diabroticites probably started ca. 62 Mya. This would be just after the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, a harsh climatic period of Earth’s history associated with a global biodiversity turnover. The initial radiation process can be attributedto the acquisition of Cucurbitaceae as a new plant host, and consequently to the origin of pharmacophagy. The split and further diversification of the main lineages, however, did not start until the Eocene/Oligocene boundary (ca. 34 Mya). Interestingly, this concurs with the inferred radiation date for other non-related lineages [e.g. Neotropical trogons (31 Mya,

Such Mesoamerican agricultural practices, however, originated ca. 10, 000 years ago (

As expected, the rate of diversification changed considerably among the mayor lineages of Diabroticina (Table 4). Cerotoma was the slowest lineage showing one cladogenetic event every 13.3 My. Whereas, Clade I within the genus Diabrotica speciated nearly three times faster (i.e. average splitting time 4.6 My). The rate of diversification inferred in the genus Cerotoma is D = 0.057 species per My or approximately a third of the rate observed in Clade II in Diabrotica (D = 0.187 species per My). An increment in the diet spectrum going from the oligophagous species of Cerotoma, to the polyphagous species of the fucata group encompassed in the different clades of the genus Diabrotica might explain such changes in the diversification rate. Other factors, nonetheless, could also be involved within the complex dynamics of species formation. When the phylogenetic pattern is included a similar scenario is observed. Calculations set the highest rate within Clade I (S = 0.071), and the lowest within the Cerotoma lineage (S = 0.034). Regardless of the fact that the generation time in these insects is significantly smaller than the generation time of many plants, the S values obtained for Diabroticinas are at least one order of magnitude smaller than those observed in some genera of plants that have undergone rapid events of speciation (e.g. Agave sensu lato, S = 0.320;

The evolutionary history and biodiversity patterns in the Diabroticina beetles is very complex and has been the result not only of recent climatic oscillation, but the combination of several intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Our data support the conclusion that these insects have gone through a series of dispersion and speciation events that have been the result of events occurred in Mesoamerica since the Eocene until the present. Unfortunately, we did not obtain samples from species belonging to the South American signifera group. Those samples are essential for understanding the biogeographic and diversification history of the genus Diabrotica, and for testing the hypothesis that the invasion of South America is a recent event posterior to the Panamanian uplift. Finally, the species sampling must be increased especially for the species rich South American genera in order to corroborate the ideas presented here.

We are grateful to the editors of this new volume of Research on Chrysomelidae for the invitation to contribute to this book and to expose our recent insights in Diabroticina evolution. Suggestions made by an anonymous reviewer greatly improved the clarity of this manuscript. Thanks to Jane Hudgson (Carlisle, Cumbria, UK) for the English language revision.