(C) 2013 Gontran Sonet. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Sonet G, Jordaens K, Braet Y, Bourguignon L, Dupont E, Backeljau T, De Meyer M, Desmyter S (2013) Utility of GenBank and the Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) for the identification of forensically important Diptera from Belgium and France. In: Nagy ZT, Backeljau T, De Meyer M, Jordaens K (Eds) DNA barcoding: a practical tool for fundamental and applied biodiversity research. ZooKeys 365: 307–328. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.365.6027

Fly larvae living on dead corpses can be used to estimate post-mortem intervals. The identification of these flies is decisive in forensic casework and can be facilitated by using DNA barcodes provided that a representative and comprehensive reference library of DNA barcodes is available.

We constructed a local (Belgium and France) reference library of 85 sequences of the COI DNA barcode fragment (mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene), from 16 fly species of forensic interest (Calliphoridae, Muscidae, Fanniidae). This library was then used to evaluate the ability of two public libraries (GenBank and the Barcode of Life Data Systems – BOLD) to identify specimens from Belgian and French forensic cases. The public libraries indeed allow a correct identification of most specimens. Yet, some of the identifications remain ambiguous and some forensically important fly species are not, or insufficiently, represented in the reference libraries. Several search options offered by GenBank and BOLD can be used to further improve the identifications obtained from both libraries using DNA barcodes.

Forensic entomology, COI, DNA barcoding, BLAST

Insects collected on crime scenes can be used to estimate the time elapsed between death and corpse discovery, i.e. the post mortem interval or PMI (

In order to be of interest in court, species identifications provided by a specific reference library should be validated by assessing the likelihood of incorrect identifications using that library (

The presence of pseudogene sequences and misidentified specimens in reference libraries is another problem that can constrain identification success (

Accurate identification of forensically important insects has been obtained using mitochondrial markers like the cytochrome c oxidase subunits I and II (COI and COII), cytochrome b, 16S rDNA, NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5, as well as nuclear markers like the ribosomal internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2, and the developmental gene bicoid (

In Western Europe, COI sequences from ca. 50 species of Sarcophagidae, ca. 10 species of Calliphoridae and five species of Muscidae are currently available as reference data for the identification of dipterans of forensic interest (

We collected 85 adult specimens of 16 dipteran species of forensic interest from 24 localities in Belgium and three localities in France (Table 1). All Belgian specimens came from forensic cases. Three specimens from three species (Neomyia cornicina, Polietes lardarius and Eudasyphora cyanella) were collected on corpses but are currently not used for the calculation of the PMI. The French specimens of Chrysomya albiceps and Lucilia sericata were not collected on corpses, but were added because of their forensic interest. Morphological species identification was done by two taxonomic experts of Diptera (YB and ED), using five identification keys (

Morphological identification and geographic origin of all specimens sampled in this study. Process ID of each sequence in the Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) is given. For each haplotype (identified here by a number), the similarity of the best match (BM) retrieved from GenBank or BOLD using five search procedures is in italic if identification was ambiguous and normal font if identification was unambiguous. Ambiguous identifications where the best correct and the best incorrect matches had the same similarity with the query are indicated by an asterisk; best correct matches were more similar to the query than best incorrect matches in all other ambiguous identifications. No value is given when best matches were all of < 99% similarity and “na” when longer COI fragments were not available. Search procedures are: barcode fragment (642–658 bp) submitted to GenBank (1), to the public records of BOLD (2), to the species level records of BOLD including early releases (3), to the records of GenBank that are tagged as barcodes (4) and longer COI fragment (1412–1534 bp) submitted to GenBank (5).

| Family | Species | Country | Locality | BOLD Process ID | Barcode fragment: haplotype ID | Longer COI fragment: haplotype ID | Similarity with BM in procedures 1 & 2 (%) | Similarity with BM in procedure 3 (%) | Similarity with BM in procedure 4 (%) | Similarity with BM in procedure 5 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calliphoridae | Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 | Belgium | Saint–Gilles/Sint–Gillis | NICC001-13 | 1 | 1 | 99.72* | 99.83* | 99.54 | 99.03 |

| Belgium | Schaerbeek/Schaarbeek | NICC002-13 | 2 | na | 100* | 100* | 99.85 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC003-13 | 2 | 2 | 100* | 100* | 99.85 | 99.05 | ||

| Belgium | Hastière | NICC004-13 | 2 | 3 | 100* | 100* | 99.85 | 99.23 | ||

| Belgium | Humbeek | NICC005-13 | 2 | 4 | 100* | 100* | 99.85 | 99.16 | ||

| Belgium | Ixelles/Elsene | NICC006-13 | 3 | 5 | 99.72* | 99.83* | 99.54 | |||

| Belgium | Auderghem/Oudergem | NICC007-13 | 2 | 3 | 100* | 100* | 99.85 | 99.23 | ||

| Belgium | Lier | NICC008-13 | 4 | na | 100* | 100* | 99.85 | na | ||

| Belgium | Gent | NICC009-13 | 5 | 6 | 99.86* | 100* | 99.7 | |||

| Belgium | Saintes | NICC010-13 | 6 | 7 | 99.86* | 99.6* | 99.7 | 99.1 | ||

| Belgium | Bruxelles/Brussel | NICC011-13 | 2 | 3 | 100* | 100* | 99.85 | 99.23 | ||

| Belgium | Hastière | NICC012-13 | 7 | 8 | 99.86* | 99.86* | 99.7 | 99.03 | ||

| Belgium | Auderghem/Oudergem | NICC013-13 | 8 | 9 | 100* | 100* | 100 | 99.1 | ||

| Belgium | Schaerbeek/Schaarbeek | NICC014-13 | 9 | 10 | 99.72* | 99.83* | 99.54 | 99.03 | ||

| Calliphora vomitoria (Linnaeus, 1758) | Belgium | Toernich | NICC015-13 | 10 | na | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | na | |

| Belgium | Hastière | NICC016-13 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | 99.02 | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC017-13 | 11 | 12 | 99.58 | 100 | 99.38 | |||

| Belgium | Schaerbeek/Schaarbeek | NICC018-13 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | 99.02 | ||

| Belgium | Genk | NICC019-13 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | 99.02 | ||

| Belgium | Laeken/Laken | NICC020-13 | 10 | 13 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | |||

| Belgium | Liège | NICC021-13 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | 99.02 | ||

| Belgium | Saintes | NICC022-13 | 10 | 14 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | |||

| Belgium | Steendorp | NICC023-13 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | 99.02 | ||

| Belgium | Gent | NICC024-13 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | 99.02 | ||

| Belgium | Hastière | NICC025-13 | 10 | na | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | na | ||

| Belgium | Schaerbeek/Schaarbeek | NICC026-13 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | 99.02 | ||

| Belgium | Genk | NICC027-13 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | 99.02 | ||

| Belgium | Sint–Laureins | NICC028-13 | 10 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | 99.02 | ||

| Belgium | Schoonaarde | NICC029-13 | 12 | 15 | 99.86 | 100 | 98.94 | |||

| Belgium | Antwerpen | NICC030-13 | 10 | na | 100 | 100 | 99.09 | na | ||

| Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann, 1819) | France | St Pourçain/Sioule | NICC031-13 | 13 | 16 | 100 | 100 | 99.29 | ||

| France | St Pourçain/Sioule | NICC032-13 | 14 | na | 100 | 100 | na | |||

| France | St Pourçain/Sioule | NICC033-13 | 15 | 17 | 99.86 | 100 | 99.23 | |||

| France | St Pourçain/Sioule | NICC034-13 | 13 | 16 | 100 | 100 | 99.29 | |||

| France | St Pourçain/Sioule | NICC035-13 | 14 | na | 100 | 100 | na | |||

| France | Sarreguemines | NICC036-13 | 13 | 16 | 100 | 100 | 99.29 | |||

| Belgium | Meerdaalwoud | NICC037-13 | 16 | na | 99.86 | 100 | na | |||

| Cynomya mortuorum (Linnaeus, 1761) | Belgium | NICC038-13 | 17 | 18 | 99.73 | 100 | ||||

| Lucilia ampullacea Villeneuve, 1922 | Belgium | Flémalle | LUCIL001-12 | 18 | 19 | 100 | 100 | 99.23 | ||

| Belgium | Flémalle | LUCIL002-12 | 19 | 20 | 99.86 | 99.86 | 99.1 | |||

| Lucilia sericata (Meigen, 1826) | Belgium | Hastière | LUCIL061-12 | 20 | 21 | 99.86 | 100 | 100 | 99.23 | |

| Belgium | Auderghem/Oudergem | LUCIL062-12 | 21 | na | 100 | 100* | 100 | na | ||

| Belgium | Gent | LUCIL063-12 | 22 | 22 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.16 | ||

| Belgium | Lier | LUCIL064-12 | 22 | 23 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.23 | ||

| France | Le Soler | LUCIL065-12 | 22 | 24 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.29 | ||

| France | Le Soler | LUCIL066-12 | 23 | 25 | 99.86 | 100* | 100 | 99.23 | ||

| Belgium | LUCIL067-12 | 22 | 24 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.29 | |||

| Belgium | Auderghem/Oudergem | LUCIL068-12 | 24 | 26 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.23 | ||

| Belgium | Schaerbeek/Schaarbeek | LUCIL069-12 | 25 | 27 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.16 | ||

| Belgium | Genk | LUCIL070-12 | 22 | 24 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.29 | ||

| Belgium | Genk | LUCIL071-12 | 26 | 28 | 99.86 | 100* | 100 | 99.23 | ||

| France | LUCIL072-12 | 22 | 29 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.23 | |||

| France | LUCIL073-12 | 22 | 29 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.23 | |||

| France | LUCIL074-12 | 22 | 29 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.23 | |||

| France | LUCIL075-12 | 22 | 29 | 100 | 100* | 100 | na | |||

| France | LUCIL076-12 | 22 | 29 | 100 | 100* | 100 | 99.23 | |||

| Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) | Belgium | Andrimont | NICC056-13 | 27 | na | 99.86 | 100 | 99.7 | na | |

| Belgium | Auderghem/Oudergem | NICC057-13 | 27 | na | 99.86 | 100 | 99.7 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC058-13 | 28 | na | 100 | 100 | 99.85 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC059-13 | 27 | na | 99.86 | 100 | 99.7 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC060-13 | 27 | na | 99.86 | 100 | 99.7 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC061-13 | 29 | na | 100 | 100 | 99.85 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC062-13 | 28 | na | 100 | 100 | 99.85 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC063-13 | 30 | na | 100 | 100 | 100 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC064-13 | 28 | na | 100 | 100 | 99.85 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC065-13 | 31 | na | 99.72 | 100 | 99.85 | na | ||

| Belgium | Andrimont | NICC066-13 | 28 | na | 100 | 100 | 99.85 | na | ||

| Belgium | Auderghem/Oudergem | NICC067-13 | 27 | na | 99.86 | 100 | 99.7 | na | ||

| Fanniidae | Fannia sp1 | Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC040-13 | 32 | 30 | 100 | |||

| Fannia sp2 | Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC041-13 | 33 | 31 | 100 | ||||

| Fannia sp3 | Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC042-13 | 34 | 32 | |||||

| Muscidae | Eudasyphora cyanella (Meigen, 1826) | Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC039-13 | 35 | 33 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Musca autumnalis De Geer, 1776 |

Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC043-13 | 36 | 34 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Muscina levida (Harris, 1780) | Belgium | Pecq | NICC044-13 | 37 | 35 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Belgium | Pecq | NICC045-13 | 38 | 36 | 99.85 | 100 | 99.85 | |||

| Belgium | Pecq | NICC046-13 | 37 | 37 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Belgium | Pecq | NICC047-13 | 37 | 35 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC048-13 | 37 | 38 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Muscina prolapsa (Harris, 1780) | Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC049-13 | 39 | 39 | 99.85 | ||||

| Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC050-13 | 39 | na | 99.85 | |||||

| Belgium | Saint–Gilles/Sint–Gillis | NICC051-13 | 40 | 40 | 100 | |||||

| Belgium | Saint–Gilles/Sint–Gillis | NICC052-13 | 40 | 40 | 100 | |||||

| Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC053-13 | 40 | na | 100 | na | ||||

| Neomyia cornicina (Fabricius, 1781) | Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC054-13 | 41 | 41 | |||||

| Polietes lardarius (Fabricius, 1781) | Belgium | Soignes/Zoniën forest | NICC055-13 | 42 | 42 | 99.84 | 99.85 |

We extracted genomic DNA from one or two legs per specimen using the NucleoSpin Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel) and a final elution volume of 70 µl. Fragments of the COI marker were amplified using two primer pairs TY-J-1460/C1-N-2191 and C1-J-2183/TL2-N-3014 (

We assembled and aligned sequences in SeqScape v2.5 (Applied Biosystems) and confirmed the absence of stop codons using MEGA5 (

Haplotypes were then used as queries to search for most similar sequences in two public databases: GenBank (NCBI, National Centre for Biotechnology) and BOLD (the Barcode of Life Data Systems). These most similar sequences will be called “best matches” sensu

In total, we applied five search strategies by submitting the barcode sequences to 1) GenBank, 2) the Public Records of BOLD, 3) the Species Level Records of BOLD including early releases, as well as 4) by using the barcode sequences as queries in combination with a keyword, “barcode”, in GenBank, and 5) by submitting COI sequences longer than the barcode fragment (1412–1534 bp) to GenBank. The use of the keyword “barcode” allowed us to filter the GenBank reference sequences and obtain only best matches that are tagged as barcodes, not only in the field “keyword” but also in any field of GenBank records. Longer COI sequences have not been submitted to BOLD because BOLD was developed to accept sequences from the strict barcode region only. In BOLD, IDS returns a list of maximum 99 best matches and provides a species-level identification for best close matches showing less than 1% divergence (

In total 85 sequences were obtained with more than 641 bp of the COI DNA barcode fragment, representing 42 haplotypes. The majority of them (63 sequences) involved a longer COI fragment (1412–1534 bp), representing 42 other haplotypes. Pairwise intraspecific p-distances ranged from zero to 0.5% and none of the species represented in this dataset shared haplotypes.

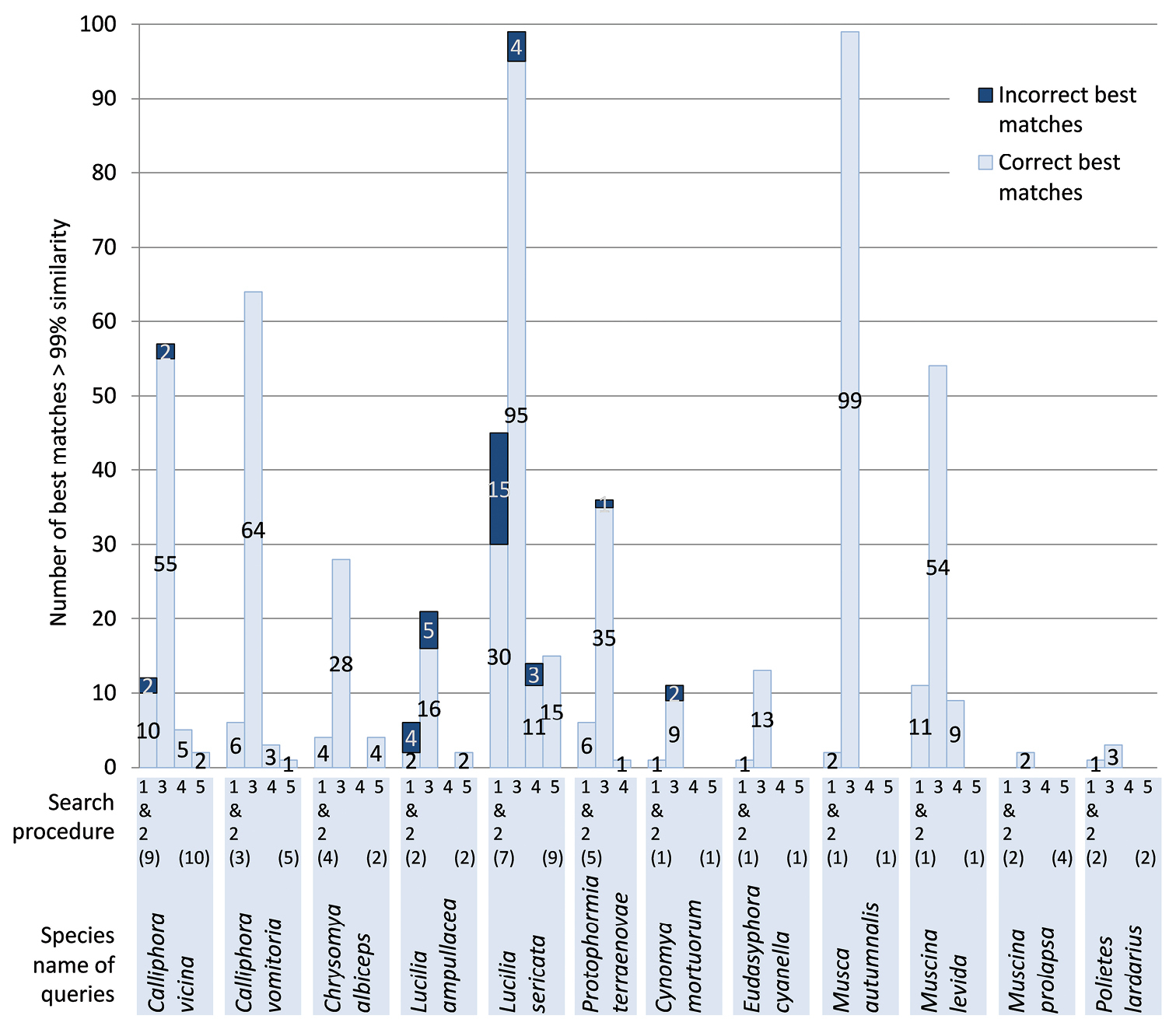

Using the 42 haplotypes of the barcode region as a query yielded the same results in GenBank and in the Public Record Barcode Database of BOLD. Best matches of > 99% similarity were retrieved for 36/42 haplotypes, representing 11 out of 16 species (Table 1). These best matches were either identical (17/36) or differed from the query in less than three substitutions (19/36). We obtained at least one correct best match for each query. However, species identifications were either unambiguous (18 queries, 8 species) or ambiguous (18 queries, 3 species). For two queries, best matches included species of another genus: Musca domestica Linnaeus, 1758was found for Calliphora vicina and Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794) for Lucilia ampullacea. In all other cases of ambiguous identification, best matches involved congenerics: Calliphora croceipalpis Jaennicke, 1867 was found for Calliphora vicina, Lucilia cuprina (Wiedemann, 1830) for Lucilia sericata and Lucilia porphyrina (Walker, 1856) for Lucilia ampullacea. Finally, the number of best matches with > 99% similarity varied from one to more than 99 per query (the number of best matches displayed by BOLD is limited to 99). For five species, less than five sequences with a similarity of > 99% were retrieved (Figure 1).

Best matches obtained for each species using five different search procedures:Barcode fragment (642–658 bp) submitted to GenBank (1) and the public records of BOLD (2); barcode fragment submitted to the species level records of BOLD, including early-released sequences (3); barcode fragment and keyword “barcode” submitted to GenBank (4) and longer COI fragment (1412–1534 bp) submitted to GenBank (5). Numbers of haplotypes used as queries are between parentheses. Longer COI fragments were obtained for all species except for Protophormia terraenovae.

For six queries, the best matching similarities were < 93.5%. These included the haplotypes of Fannia sp1, sp2 and sp3, Muscina prolapsa and Neomyia cornicina. There were no COI sequences of Muscina prolapsa or of Neomyia cornicina in GenBank. For Fannia, fragments of the barcode region of > 500 bp were available for 14 specimens representing four species, viz. Fannia canicularis (Linnaeus, 1761), Fannia scalaris (Fabricius, 1794), Fannia brevicauda Chillcott, 1961 and Fannia serena (Fallen, 1825) but their p-distances with our three Fannia haplotypes ranged from 6.6% to 16.2%.

Using the Species Level Barcode Records dataset of BOLD (Table 1), highly similar best matches (> 99%) were retrieved for 40/42 queries (14/16 species). Correct best matches were retrieved for all specimens identified at the species level, but identifications were often ambiguous (25 queries, 6 species). This method yielded a higher proportion of best matches of > 99% similarity than when the search was restricted to public records (95% of the queries instead of 86%). However, the proportion of unambiguous identifications was smaller (38% instead of 50% of the queries; Table 2). Yet, in contrast to all the other searches, early-released sequences provided two correct matches for Muscina prolapsa, one match for Fannia sp2 and three matches for Fannia sp1 (correct at the genus level). The latter identification was ambiguous since two best matches showed 100% similarity with Fannia lustrator (Harris, 1780) and one showed 99.85% similarity with Fannia pallitibia (Rondani, 1866). The two queries for which best matches were of < 99% similarity were from Fannia sp3 and Neomyia cornicina. No barcodes were available for Neomyia cornicina in BOLD.

Evaluation of the DNA-based identifications obtained in this study using five search procedures: barcode fragment submitted to GenBank (1), to the public records of BOLD (2), to the species level records of BOLD including early releases (3), to the records of GenBank that are tagged as barcodes (4) and longer COI fragment submitted to GenBank (5). Only best matches of > 99% similarity were considered. OK: correct unambiguous identification; OK +: ambiguous identification due to correct and incorrect best matches (species names associated with incorrect best matches are given with the abbreviated genus name in case of congeneric matches); *: ambiguous identifications where the best correct and the best incorrect matches had the same similarity with the query; best correct matches were more similar to the query than best incorrect matches in all other ambiguous identifications; na: longer COI fragment not available; empty cell: no best match above 99% similarity. Numbers without parentheses were obtained with the barcode fragment and numbers between parentheses were obtained with the longer COI fragment. In order to allow comparisons between the results obtained with the barcode and the longer COI datasets, values obtained with the barcode fragment of the sequences for which the longer COI fragment was available are given between brackets.

| Species | Number of haplotypes | Search procedure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 & 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Calliphora vicina | 9 (10) | OK + Calliphora croceipalpis*, Musca domestica* | OK + Calliphora croceipalpis*, Musca domestica* | OK | OK |

| Calliphora vomitoria | 3 (5) | OK | OK | OK | OK |

| Chrysomya albiceps | 4 (2) | OK | OK | OK | |

| Lucilia ampullacea | 2 (2) | OK + Lucilia porphyrina, Chrysomya megacephala | OK + Chrysomya megacephala | OK | |

| Lucilia sericata | 7 (9) | OK + Lucilia cuprina | OK + Lucilia cuprina* | OK + Lucilia cuprina | OK + Lucilia cuprina |

| Protophormia terraenovae | 5 (0) | OK | OK + Protophormia uralensis | OK | na |

| Fannia sp1 | 1 (1) | Fannia pallitibia, Fannia lustrator | |||

| Fannia sp2 | 1 (1) | Fannia manicata | |||

| Fannia sp3 | 1 (1) | ||||

| Cynomya mortuorum | 1 (1) | OK | OK + Cynomya cadaverina | ||

| Eudasyphora cyanella | 1 (1) | OK | OK | ||

| Musca autumnalis | 1 (1) | OK | OK | ||

| Muscina levida | 2 (4) | OK | OK | OK | |

| Muscina prolapsa | 2 (2) | OK | |||

| Neomyia cornicina | 1 (1) | ||||

| Polietes lardarius | 1 (1) | OK | OK | ||

| % of species with matches > 99% similarity | 69[67] | 88[87] | 31[27] | (33) | |

| % of queries with matches > 99% similarity | 86[86] | 95[95] | 62[67] | (67) | |

| % of species with unambiguous ID | 73[70] | 57[62] | 80[75] | (80) | |

| % of queries with unambiguous ID | 50[42] | 38[42] | 73[68] | (68) | |

| % of species with ambiguous ID | 27[30] | 43[38] | 20[25] | (20) | |

| % of queries with ambiguous ID | 50[58] | 62[58] | 27[32] | (32) | |

When both the barcode sequences and the keyword “barcode” were used as queries in GenBank, we retrieved best matches of > 99% similarity for Calliphora vicina, Calliphora vomitoria, Lucilia sericata, Protophormia terraenovae and Muscina levida (Tables 1 and 2). All best matches of > 99% similarity were correct and provided unambiguous identifications except for Lucilia sericata, which matched with both correct and incorrect species names (Lucilia cuprina and Lucilia sericata).

Haplotypes of longer COI fragments (1412–1534 bp) were also submitted to a MegaBLAST search on GenBank. Best matches of > 99% similarity were obtained for all haplotypes of Calliphora vicina, Calliphora vomitoria, Chrysomya albiceps, Lucilia ampullacea and Lucilia sericata. Like in the previous analysis, all best matches were correct and provided unambiguous identifications except for Lucilia sericata (best matches included Lucilia sericata and Lucilia cuprina).

With this study we contributed to the establishment of a local COI reference library for fly species of forensic importance in Belgium and France. As such, we provide the first barcodes for Muscina prolapsa and Neomyia cornicina. We also extended the geographic coverage of barcodes of species which hitherto were only sampled from a limited number of localities, e.g. Cynomya mortuorum and Polietes lardarius were each represented by only one barcode sequence from the UK (

For 86% of the barcode fragments used as queries, we retrieved highly similar conspecific sequences (> 99% similarity) from GenBank and BOLD. The more divergent best matches (< 99% similarity) obtained for the remaining 14% of the queries would have produced either incorrect (Muscina prolapsa and Neomyia cornicina) or doubtful identifications (Fannia) if all best matches were taken into account for identification. The better performance of the best close match method compared to the simple best match method has already been reported (e.g.

Our results showed that some fly species collected at Belgian crime scenes are not represented by COI records in GenBank and BOLD. Muscina prolapsa, for which no barcode sequence is present in GenBank, colonises carrion and buried remains (

Identifications based on the barcode fragment were ambiguous for 50% of the queries and for 27% of the species. Some ambiguous identifications can result from misidentified sequences in the libraries and could be corrected after re-examining the voucher specimens (

Still, most ambiguous identifications involved closely related species that are not necessarily incorrectly identified (

Similarity values between the query and its best matches can be calculated using several methods. Here, similarities with GenBank records were determined as 1 - p-distances but no explicit information was found on the exact method used by the IDS of BOLD to determine the similarity values. Even if the IDS of BOLD applied a different method than ours, – distances are standardly corrected using the Kimura 2-parameter model (

It is striking that identifications provided by GenBank and BOLD for the barcode fragment were either ambiguous or involved a rather limited number of very similar reference sequences (Figure 1). Therefore, we tested alternative search strategies to optimise the number of best matches and minimise the number of ambiguous identifications. For this, we used different options offered by GenBank and BOLD by 1) including early releases from BOLD in the reference library, 2) adding the keyword “barcode” as a query in GenBank and 3) using longer COI sequences as queries in GenBank.

Including early releases as reference sequences in BOLD increased the number of best matches of > 99% similarity but also increased the proportion of ambiguous identifications (Table 1). Early releases might not have passed all controls that authors and reviewers make in the process of publication (e.g.

In order to improve the search for sequences that have been produced for DNA barcoding purposes, we added the word “barcode” to each query in GenBank. With this procedure, the number of best matches of > 99% similarity and the proportion of ambiguous matches drastically decreased. The same tendency was observed when longer COI sequences (1412–1534 bp) were used as queries. This is due to the smaller number of reference sequences that are tagged as barcodes or are longer than the standard barcode fragment. Therefore, this kind of search is currently only relevant for the identification of fly species of forensic interest that are well represented by longer COI reference sequences or that are tagged as barcodes. Moreover, longer DNA fragments are not always easy to sequence from degraded forensic samples (

Even if BOLD and GenBank contain the same public records, they offer different options for optimizing their use as reference libraries. For barcode data, we recommend using the BOLD Identification System and searching the dataset including early-released sequences (Species Level Barcode Records). This option optimises the number of best-matches and allows to verify the quality of the data (published or early-released sequence, barcode compliant or not, link with voucher specimens, etc.). When working with reference material, we encourage the early release of the data and the correction of any mistake detected at this stage (e.g. misidentification). Furthermore, entering sequences into a BOLD project gives access to a workbench with supplementary tools (tables with best matches, best close matches and construction of Neighbour-Joining trees), that are useful for quality control (

We wish to thank the teams of the DNA and Microtraces Analysis (NICC), especially Dr. F. Hubrecht, Dr. S. Vanpoucke, and Dr. F. Noel for their support during our work. We also thank the reviewers of the manuscript for their very constructive and pertinent comments. This research is part of the BC42W project and was carried out by the Joint Experimental Molecular Unit – JEMU, which is financed by the Belgian Science Policy Office (BELSPO).