(C) 2013 Sophie Verscheure. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Citation: Verscheure S, Backeljau T, Desmyter S (2013) Reviewing population studies for forensic purposes: Dog mitochondrial DNA. In: Nagy ZT, Backeljau T, De Meyer M, Jordaens K (Eds) DNA barcoding: a practical tool for fundamental and applied biodiversity research. ZooKeys 365: 381–411. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.365.5859

The identification of dog hair through mtDNA analysis has become increasingly important in the last 15 years, as it can provide associative evidence connecting victims and suspects. The evidential value of an mtDNA match between dog hair and its potential donor is determined by the random match probability of the haplotype. This probability is based on the haplotype’s population frequency estimate. Consequently, implementing a population study representative of the population relevant to the forensic case is vital to the correct evaluation of the evidence. This paper reviews numerous published dog mtDNA studies and shows that many of these studies vary widely in sampling strategies and data quality. Therefore, several features influencing the representativeness of a population sample are discussed. Moreover, recommendations are provided on how to set up a dog mtDNA population study and how to decide whether or not to include published data. This review emphasizes the need for improved dog mtDNA population data for forensic purposes, including targeting the entire mitochondrial genome. In particular, the creation of a publicly available database of qualitative dog mtDNA population studies would improve the genetic analysis of dog traces in forensic casework.

Forensics, Mitochondrial DNA, Dog, Random match probability, Population study, Sampling strategy

Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) are common and widespread in human society and hence, dog trace material is frequently encountered in forensic casework. Usually, this trace material involves hair, which is easily dispersed either through immediate contact with a dog or indirectly via an intermediate carrier, thus leaving a signature of the dog. Consequently, determining whether a particular dog could have donated the hair found at a crime scene may provide associative evidence (dis)connecting victims and suspects. For example, dog hairs could have been transferred from a victim’s clothes to the trunk of a perpetrator’s car during transportation of a body. Linking these hairs to the victim’s dog could connect the suspect to the crime.

Most dog hairs collected at crime scenes are naturally shed and are in the telogen phase. As such, because they contain only limited amounts of, usually degraded, nuclear DNA (nDNA), they are ill suited for nDNA analysis. Conversely, mainly as a result of its high copy number and much smaller size (

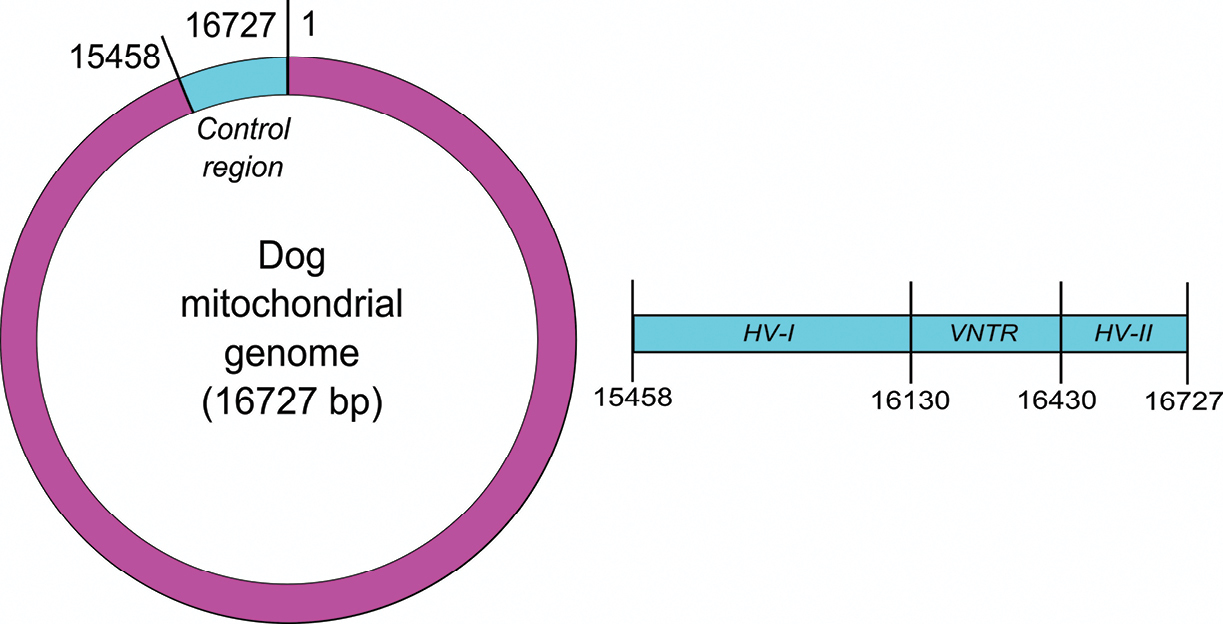

Position of the control region and its subregions within the

In general, mtDNA is maternally inherited (

The random match probability is determined by the frequency estimate of the haplotype in the population of interest. The more common a haplotype, the higher is the probability that two dogs share this haplotype by chance, thus decreasing the evidential value of a match with this mtDNA type. Consequently, this sort of forensic applications requires the accurate estimation of haplotype frequencies in a population relevant to the criminal case.

The goal of this publication is to draw people’s attention to the importance of implementing a dog mtDNA population study representative of the population of interest in a forensic case. It will provide an overview of the most important issues to keep in mind both when performing a population study of your own, as well as when considering to use published mtDNA data. First of all, sampling strategy characteristics are discussed such as sample size, maternal relatedness, breed status of the sampled dogs, and their geographic origin. Next, the importance of the quality of the sequence data is emphasized. In addition, the need to expand the sequenced DNA fragment in dog mtDNA studies is illustrated. Finally, the advantages of, and the criteria for, the assembly of an international, publicly available dog mtDNA population database of the highest quality, are pinpointed.

The accuracy of haplotype frequency estimates almost entirely depends on the characteristics of the population sample that is used to represent the relevant population, i.e. the population to which the donor of the trace is supposed to belong. Hence, biased population samples may lead to haplotype frequency estimates that diverge from the true population values.

To explore the impact of biased reference population samples in dog studies, we relied on current practices in human mtDNA population analyses and data derived from a selection of papers on haplotype variation in the dog mtDNA control region or the entire mitochondrial genome (mtGenome). Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the 58 dog studies used in this review. It includes studies with forensic aims, but also phylogenetic population and breed studies.

Overview of the characteristics of sampling and sequence analysis in 58 canine mtDNA studies. Number of dogs sampled and, when specified in the publication, the number of dog breeds and mixed-breed, feral or village dogs in the sample; Origin of sample: new or extracted from previous studies as a comparison or to supplement the population sample (see reference numbers, except unpublished data by van Ash et al. (59); Koop et al. (60) and Shahid et al. (61)); Sampling region (or the geographic region of origin of included dog breeds if unclear from publication); Intention to avoid the inclusion of maternal relatives; GenBank accession numbers of new data are stated when applicable; un, unknown; s, skeletal remains of various age; ±, when variable, all sequences extracted from GenBank or the publication have this region in common; <, selected from this number of dogs from the same publication; * Larger region is mentioned in the publication, but only this part is available; Characteristics can differ from what is stated in publication if potential clerical errors were adapted, e.g. **publication states 246 instead of 233 as the sequences from reference 22 were included twice.

| Publication | Sample | Sequence analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Aim of study | # Dogs | # Breeds | # Mixed- breed | Origin of sample | Sampling region | Avoid relatives | mtDNA region | Availability of new sequence data | |

| 1 | mtDNA variability study | 11 | 11 | 0 | new | the Netherlands | un | Repeat region* | Publication | |

| 2 | Phylogenetic breed study | 94 | 24 | 0 | new | Japan | un | 15458-16129, 16420-16727 | D83599-D83613, D83616-D83638 | |

| 3 | Forensic, Phylogenetic | 102 | 52 | 0 | new | Sweden | YES | 15431-15687 | Publication | |

| Population study | ||||||||||

| 4 | Phylogenetic population study | 34 | 24 | 0 | new | Japan, Korea, Mongolia, Indonesia | un | 15458-16130* | AB007380-AB007403 | |

| 5 | Phylogenetic population study | 140 | 67 | 5 | new | un | un | 15431-15687 | AF005280-AF005295 | |

| 15 | un | un | < 140 new | ± 15393-16076, ± 16508-49 | AF008143-AF008157, AF008168-AF008182 | |||||

| 6 | First complete dog mtGenome | 1 | 1 | 0 | new | Korea | YES | 1-16727 | U96639 | |

| 7 | Phylogenetic breed study | 74s | un | un | new | Japan | un | 15483-15679 | AB031089-AB031107 | |

| 84 | un | un | new | |||||||

| 94 | 24 | 0 | 2 | 15458-16129, 16420-16727 | ||||||

| 8 | Phylogenetic breed study | 19 | 1 | 0 | new | US, Mexico | YES | 15431-15687* | Publication | |

| 140 | 67 | 5 | 5 | un | 15431-15687 | |||||

| 9 | Phylogenetic population study | 41 | 30 | 0 | new | Switzerland | un | 15458-16000 | AF115704-AF115718 | |

| 9 | 0 | 9 | new | Italy | ||||||

| 10 | Phylogenetic breed study | 25 | 11 | 0 | new | Korea | NO | 15622-16030 | AF064569-AF064579, AF064581-AF064585 | |

| 11 | Forensic population study | 12 | 11 | 1 | new | Poland | un | 15431-15687 | AF345977-AF345982 | |

| 12 | Phylogenetic population study | 526 | un | un | new | Europe, Asia, Africa, Arctic America | un | ± 15458-16039 | AF531654-AF531741 | |

| 128 | 2, 4 | |||||||||

| 13 | Inheritable disorder study | 365 | 49 | un | new | Japan | un | 15458-16055 | AB055010-AB055055 | |

| 14 | Phylogenetic population study | 50 | un | un | new | France, Switzerland | un | ± 15519-15746 | AF487730-AF487735 (excl. AF487732), | |

| 15 | un | un | new | France, Portugal | AF487747-AF487751, AF338772-AF338788 | |||||

| 15 | Forensic population study | 105 | un | un | new | UK | un | 15431-16030 | AY928903-AY928932 | |

| 246 | 2, 3, 9 | Japan, Switzerland, Italy, Sweden | ± 15458-15687 | |||||||

| 16 | Pereira et al. 2004 | Catalogue of published datasets | 58 | 1 | 0 | 59 | Portugal | un | 15458-16039 | Publication |

| 1089 | un | un | 2, 4, 10, 12, 13, 15 | Europe, Asia, Africa, Arctic America | ± 15622-16030 | |||||

| 17 | Phylogenetic population study | 22 | un | un | new | SE-Asia, India | un | 15458-16039 | AY660647-AY660650 | |

| 19s | un | un | new | Polynesia | 15458-15720 | Publication | ||||

| 654 | un | un | 2, 4, 12 | Europe, Asia, Africa, Arctic America | ± 15458-16039 | |||||

| 18 | Phylogenetic population study | 24 | 0 | 24 | new | India | un | 15443-15783 | AY333727-AY333737 | |

| 19 | Forensic, Phylogenetic | 35 | 19 | 9 | new | Germany | YES | 15458-16039 | AY656703-AY656710 | |

| 74 | 52 | 2 | new | Europe | ||||||

| Population study | 758 | un | un | 2, 4, 12, 15 | Europe, Asia, Africa, Arctic America | ± 15458-16030 | ||||

| 20 | Forensic population study | 348 | 88 | 45 | new | US | un | 15431-16085 | Not published | |

| 21 | Phylogenetic breed study | 143 | 4 | 0 | new | Portugal | YES | 15372-16083 | Publication | |

| 144 | 9 | 0 | 2, 4, 12, 13 | Europe, Asia, Africa, Arctic America | ± 15458-16030 | |||||

| 22 | Phylogenetic population study | 88 | 53 | 0 | new | Sweden | un | part of HV-I | Not published | |

| 14 | 13 | 0 | < 88 new | 1-16727 | DQ480489-DQ480502 | |||||

| 23 | Phylogenetic breed study | 143 | 11 | 0 | new | Portugal, Spain, Morocco | YES | 15211-16096 | AY706476-AY706524 | |

| 21 | 0 | 21 | new | Portugal, Azores, Tunisia | ||||||

| 24 | Phylogenetic breed study | 84 | 3 | 0 | new | Russia | un | 15458-15778 | DQ403817-DQ403837 | |

| 20 | 2 | 0 | 12 | Turkey | ± 15458-16039 | |||||

| 25 | Phylogenetic breed study | 100 | 20 | 0 | new | Sweden | un | 15431-15687 | Publication | |

| 26 | Forensic population study | 133 | 46 | 38 | new | Austria | un | 15458-16727 | Publication | |

| 27 | Forensic population study | 61 | 41 | 0 | new | US | un | 15455-16727 | AY240030-AY240157 | |

| Forensic breed study | 64 | 2 | 0 | new | (excluding AY240073, AY240094, AY240155) | |||||

| 28 | Forensic population study | 83 | 30 | 0 | new | US | un | 15595-15654 | Publication | |

| 159 | 27, 30 | |||||||||

| 29 | Forensic population study | 96 | 79 | 0 | new | UK | un | 15458-16039 | Not published | |

| Forensic breed study | 15 | 1 | 0 | new | 15458-16131, 16428-16727 | |||||

| 30 | Forensic population study | 36 | 11 | 20 | new | US (California) | un | 15456-16063 | EF122413-EF122428 | |

| 22 | un | un | 60 | un | 15433-16139 | AF098126-AF098147 | ||||

| 179 | 2, 4, 5, 6, 10, 27 | Europe, Asia, North-America | ± 15622-16030 | |||||||

| 31 | Phylogenetic breed study | 52 | 5 | 0 | new | Spain | un | 15458-16105 | EF380216-EF380225 | |

| 32 | Inheritable disorder study | 7 | 1 | 0 | new | Sweden | NO | 1-16727 | FJ817358-FJ817364 | |

| 33 | Phylogenetic population study | 309 | 0 | 309 | new | Egypt, Uganda, Namibia | YES | ± 15454-16075 | GQ375164-GQ375213 | |

| 17 | 0 | 17 | new | US (mostly Puerto Rico) | ||||||

| un | un | un | 12, 23 | East-Asia, Africa | ± 15458-16039 | |||||

| 34 | Forensic population study | 117 | 60 | 24 | new | Belgium | YES | 15458-16130, 16431-16727 | Not published | |

| 35 | Phylogenetic breed study | 114 | 2 | 0 | new | Turkey | YES | 15458-16039 | EF660078-EF660191 | |

| un | un | un | 12 | Europe, Asia, Africa | ||||||

| 36 | Phylogenetic population study | 907 | un | un | new, 61 | Old World, Arctic America | un | ± 15458-16039 | EU816456-EU816557 | |

| 669 | un | un | 2, 4, 6, 12, 22 | |||||||

| 135 | un | un | < 907 + 669 | 1-15511, 15535-16039, 16551-16727 | EU789638-EU789786 | |||||

| 34 | un | un | 6, 22, 61 | 1-16727 | AY656737-AY656755 | |||||

| 37 | Forensic population study | 427 | 139 | 118 | new | US | YES | ± 15458-16114, ± 16484-16727 | EU223385-EU223811 | |

| 125 | 27 | 15455-16727 | ||||||||

| 38 | Forensic population study | 64 | 43 | 11 | 37 | US | YES | ± 1-16129, ± 16434-16727 | EU408245-EU408308 | |

| 15 | 14 | 0 | 6, 22 | Korea, Sweden | 1-16727 | |||||

| 39 | Phylogenetic population study | 29 | un | un | new | Canada | un | 15361-15785 | FN298190-FN298218 | |

| 40 | Forensic population study | 220 | 0 | 220 | new | US | YES | 15456-16063 | FJ501174-FJ501203 | |

| 429 | 30, 37 | ± 15458-16063 | ||||||||

| 41 | Phylogenetic population study | 325 | un | un | new | Europe, SW-Asia | un | 15458-16039 | HQ261489, HQ452418-HQ452423, | |

| 1576 | un | un | 2, 4, 6, 12, 22, 36, 61 | Old World, Arctic America | ± 15458-16039 | HQ452432-HQ452433, HQ452466-HQ452477 | ||||

| 42 | Phylogenetic population study | 200 | 0 | 200 | new | Middle East/SW-Asia | un | 15482-15867 | HQ287728-HQ287744 | |

| 231 | 0 | 231 | new | SE-Asia | ||||||

| 1576 | un | un | 2, 4, 6, 12, 22, 36, 61 | Old World, Arctic America | ± 15458-16039 | |||||

| 43 | Phylogenetic population study | 371 | 0 | 371 | new | the Americas | un | ± 15491-15755 | HQ126702-HQ127072 | |

| 29 | un | un | 39 | |||||||

| 44 | Phylogenetic population study | 280 | 33 | 0 | new | Europe, Arctic America, East-Asia | YES | 15458-16039 | GQ896338-GQ896345 | |

| 234 | 36 | ± 15458-16039 | ||||||||

| 45 | Point heteroplasmy pedigree study | 180 | 18 | 0 | new | Europe, Arctic America, East-Asia | NO | 15458-16039 | Publication | |

| 131 | 2 | 0 | new | |||||||

| 46 | Phylogenetic breed study | 77 | 26 | 0 | new | Germany | NO | 15458-16124 | Publication | |

| 34 | 1 | 0 | new | |||||||

| 47 | Phylogenetic breed study | 1 | 1 | 0 | new | China | YES | 1-16727 | HM048871 | |

| 33 | un | un | 22, 32, 38, 61 | Sweden, US | ||||||

| 48 | Forensic species ID, Phylogenetic population study | 20 | 0 | 20 | new | Croatia | un | 15465-15744 | GU324475-GU324486 | |

| 49 | Validation of forensic analysis method | 41 | 29 | 3 | new | Belgium | un | ± 15458-16092, ± 16474-16703 | HM561524-HM561546, HQ845266-HQ845282 | |

| 550 | 27, 37 | US | ± 15458-16114, ± 16484-16727 | |||||||

| 50 | Phylogenetic breed study | 78 | 3 | 0 | new | Romania | YES | ± 15251-16068 | HE687017-HE687019 | |

| 51 | Forensic population study | 208 | 60 | 68 | new, 34 | Belgium | YES | 15458-16129, 16430-16727 | HM560872-HM560932 | |

| 778 | 15, 26, 27, 37 | UK, Austria, US | ± 15458-16030 | |||||||

| Forensic breed study | 107 | 6 | 0 | new | Belgium | 15458-16129, 16430-16727 | ||||

| 337 | 6 | 0 | < 208 new, 13, 19, 26, 27, 37 | Worldwide | ± 15458-16039 | |||||

| 52 | Phylogenetic breed study | 34 | 2 | 0 | new | Poland | NO | 15426-16085 | HM007196-HM007200 | |

| 53 | , |

un | un | un | GenBank | Worldwide | ||||

| 54 | Forensic population study | 100 | 98 | 0 | new | US, Australia, Canada, Columbia, Uruguay | YES | ± 1-16129, ± 16430-16727 | JF342807-JF342906 | |

| 233** | un | un | 6, 22, 36, 38, 61 | Worldwide | ± 1-15511; ± 15535-16039; ± 16551-16727 | |||||

| 55 | Phylogenetic breed study | 47 | 1 | 0 | new | Tibet, surrounding areas | YES | ± 582 bp of control region | Not published | |

| 439 | un | un | GenBank | Worldwide | ||||||

| 56 | Phylogenetic population study | 305 | un | un | new | SE-Asia, E-Asia | YES | 15458-16039 | HQ452439-HQ452465 | |

| 350 | un | un | 4, 12, 36 | ± 15458-16039 | ||||||

| 1224 | un | un | 2, 4, 6, 12, 22, 36, 61 | Old World, Arctic America | ||||||

| 19s | un | un | 17 | Polynesia | 15458-15720 | |||||

| 57 | Phylogenetic population study | 20s | un | un | new | Alaska, Greenland | un | ± 367 bp of HV-I | JX185397 | |

| 51 | 1 | 0 | new | Arctic America | ± 15580-16016 | |||||

| 78 | 2 | 0 | 2, 12, 36, 44 | ± 15458-16039 | ||||||

| 58 | Phylogenetic breed study | 324 | 5 | 0 | new | Canary Islands | YES | 15361-16086 | Publication | |

| 986 | un | un | 15, 26, 27, 34, 37, 51 | UK, Austria, Belgium, US | ± 15458-16030 | |||||

Dog mtDNA studies quite often do not meet the standards required for generating and publishing forensic human mtDNA population data. Briefly, these standards include: (1) providing a good documentation of the sampling strategy and a detailed description of the sampled individuals and the population, (2) avoiding sampling bias due to population substructure, (3) applying high quality mtDNA sequencing protocols and describing them clearly, (4) avoiding errors by handling and transferring data electronically, (5) performing quality checks of the generated data by e.g. haplogrouping or quasi-median network analysis and (6) making the full sequences publicly and electronically available preferably through either GenBank (

Strategies to sample mtDNA from dog populations are rarely well documented. Hence, it is often not clear to what extent the population samples adequately represent the populations from which they were drawn. Not seldom, sampling efforts are indeed limited to “sampling by convenience”, i.e. relying on opportunistic sampling from locations as veterinary clinics and laboratories, dog shows, training schools and animal shelters. Obviously, it can be doubted whether these sampling locations are representative random samples of the “free” living relevant dog community (

Several publications have provided recommendations on population sampling strategies for both dog and human mtDNA in forensics (

Using a random subsampling method (

Generally, the number of observed haplotypes increases with sample size (Table 2), while the proportion of rare haplotypes (i.e. encountered only once or twice) goes down. Consequently, exclusion probability largely remains the same with sample size expansion (

Comparison of haplotype number, PE and haplotypes with the 10 highest frequencies in selected dog mtDNA studies. Exclusion probability (PE) is based on the part of the control region studied in the publication (further details on exact region in Table 1) excluding the repeat region; characteristics can differ from publication if potential clerical errors were adapted; the 3 universally most frequent haplotypes are in bold (A11, B1 and A17); (×) US and a minority from Australia, Canada, Uruguay and Columbia; (××) Haplotype names are analogous to

| Population studies for forensic purposes | Breed studies for forensic or phylogenetic purposes | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | US | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sampling region | UK | Germany | Austria | Belgium | US | US | US | US | US (×) | Japan | US | Canary Islands | ||||||||||||

| Studied part of control region (CR) | HV-I | HV-I | entire CR | HV-I+II | entire CR | HV-I | HV-I+II | HV-I | HV-I | HV-I+II | entire CR | HV-I | ||||||||||||

| # Dogs (# breeds/# mixed-breed) | 105(un/un) | 35(19/9) | 133 (46/38) | 208 (60/68) | 61(41/0) | 36(11/20) | 552 (139/118) | 649 | 100(98/0) | 94(24/0) | 64(2/0) | 324(5/0) | ||||||||||||

| # Haplotypes | 31 | 13 | 40 | 58 | 32 | 16 | 104 | 71 | 34 | 38 | 13 | 16 | ||||||||||||

| Exclusion probability | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.8 | 0.86 | ||||||||||||

| Haplotypes with 10 highest frequency estimates (%) (××) (×××) | B1 | 14.2 | A11 | 28.6 | A11 | 18.0 | B1 | 16.8 | A11 | 14.8 | B1 | 16.7 | B1 | 15.6 | B1 | 18.0 | B1 | 17.0 | A18 | 13.8 | A33 | 29.7 | B1 | 25.9 |

| A18 | 11.4 | A17 | 14.3 | A17 | 12.0 | A11 | 15.4 | B1 | 13.1 | A11 | 13.9 | A17 | 10.9 | A11 | 12.6 | A11 | 15.0 | A68 | 10.6 | A16 | 28.1 | A17 | 14.5 | |

| A17 | 10.5 | B1 | 14.3 | B1 | 12.0 | A17 | 15.4 | A18 | 9.8 | A16 | 13.9 | A11 | 10.3 | A17 | 11.7 | A18 | 14.0 | C3 | 10.6 | B1 | 26.6 | A20 | 14.2 | |

| A2 | 8.6 | C3 | 8.6 | A19 | 8.3 | A19 | 6.7 | A17 | 6.6 | A17 | 13.9 | A18 | 9.2 | A18 | 11.1 | A17 | 8.0 | A17 | 9.6 | A5 | 6.3 | B6 | 14.2 | |

| A11 | 8.6 | A2 | 5.7 | A2 | 6.8 | A18 | 5.8 | C3 | 4.9 | A18 | 11.1 | A16 | 6.7 | A16 | 6.2 | A2 | 7.0 | B14 | 8.5 | Gundry_24 | 6.3 | A19 | 8.3 | |

| Haplotypes with 10 highest frequency estimates (%) (××) (×××) | A19 | 5.7 | A19 | 5.7 | A18 | 6.8 | A16 | 4.8 | C5 | 4.9 | A1 | 2.8 | A33 | 3.4 | A19 | 3.1 | A22 | 4.0 | A19 | 4.3 | A11 | 1.6 | A11 | 6.5 |

| A16 | 4.8 | B6 | 5.7 | A16 | 3.8 | A22 | 3.8 | A1 | 3.3 | A15 | 2.8 | C3 | 3.1 | C3 | 3.1 | A5 | 3.0 | A2 | 3.2 | A17 | 1.6 | A22 | 4.9 | |

| A20 | 3.8 | A5 | 2.9 | A1 | 3.0 | A2 | 2.4 | A2 | 3.3 | A22 | 2.8 | A2 | 2.5 | A2 | 2.5 | A16 | 3.0 | A11 | 3.2 | A17+ | 2.8 | |||

| A26 | 2.9 | A20 | 2.9 | A153 | 3.0 | C1 | 2.4 | A64 | 3.3 | A26 | 2.8 | A19 | 2.4 | A5 | 1.7 | A167* | 3.0 | B1 | 3.2 | A18 | 2.8 | |||

| A1 | 2.9 | A33 | 2.9 | A22 | 2.3 | C2 | 2.4 | C2 | 3.3 | A28 | 2.8 | A5 | 2.0 | A22 | 1.7 | A19 | 2.0 | A29 | 2.1 | A33 | 2.5 | |||

| C1 | 2.9 | A44 | 2.9 | A26 | 2.3 | Gundry_31 | 3.3 | A29 | 2.8 | C2 | 1.7 | A24 | 2.0 | A70 | 2.1 | |||||||||

| A70 | 2.9 | A33 | 2.3 | A64 | 2.8 | A72 | 2.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| A82 | 2.9 | C1 | 2.3 | A140 | 2.8 | B12 | 2.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| A156 | 2.8 | C1 | 2.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| B3 | 2.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| C3 | 2.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

A randomized population sample for forensics should be allowed to include relatives if it is supposed to be unbiased (

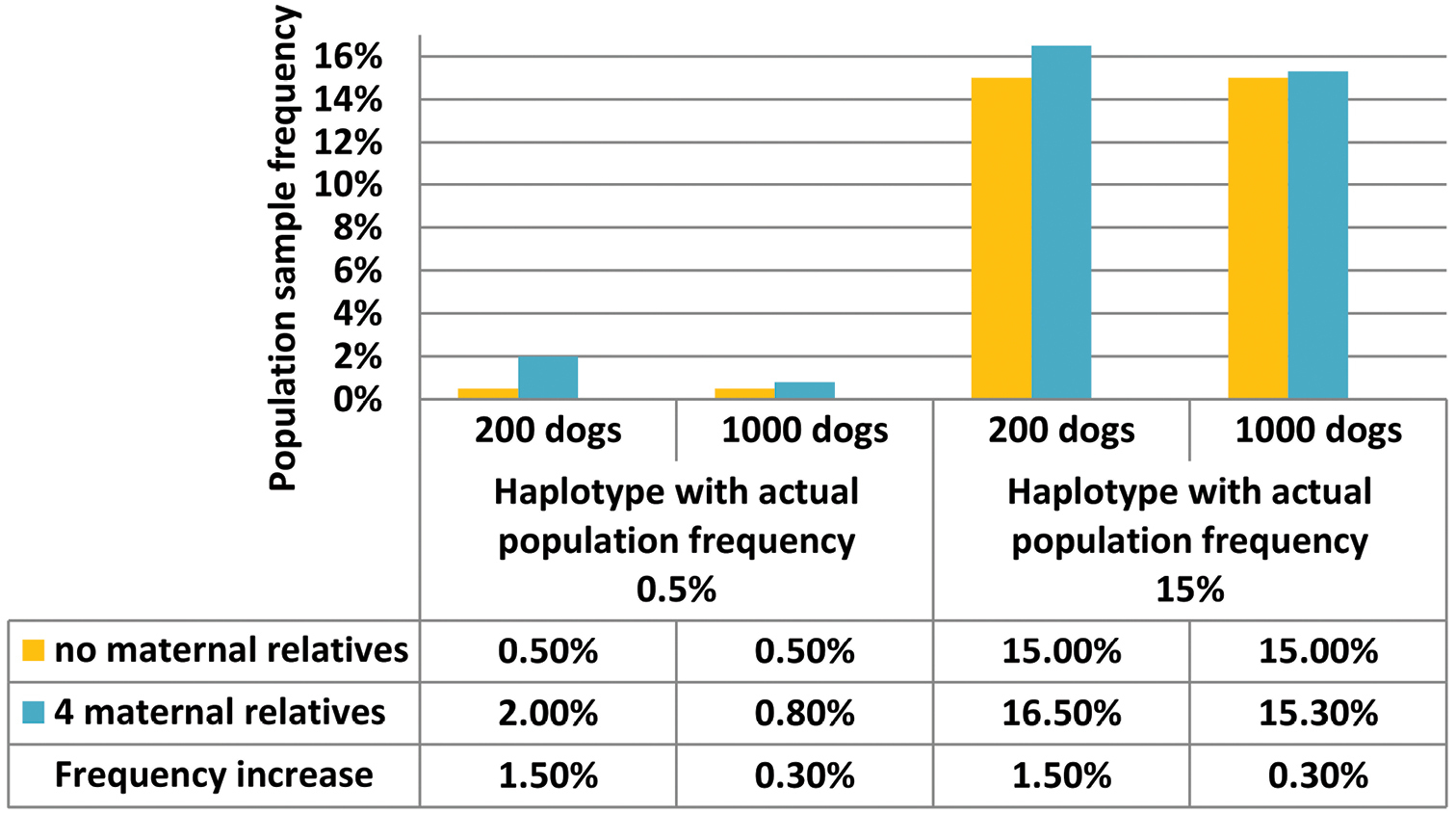

The impact of a biased inclusion of maternal relatives in a forensic population study is rarely addressed, but generally decreases the genetic diversity of the population sample (

Impact of including maternally related dogs in population samples of 200 versus 1000 dogs on the estimation of the frequencies of rare haplotypes.

Although not specifically mentioned as a criterion for human mtDNA data in the international EMPOP database (

For dog studies there is no consistent practice in dealing with maternal relationships in the population samples. Only about half of the 58 dog mtDNA studies in Table 1 mention whether or not they had the intention to avoid maternal relatives. Obviously, the usefulness of studies that do not provide this information may be doubtful in forensics. How maternal relationships were assessed is often not specified either, but it usually involves collecting information about the dogs from their owners. These background records can be used to verify whether dogs sharing a haplotype are e.g. from the same breed or whether their places of residence or those of their parents coincide (

Another characteristic that can affect the haplotype frequency distribution in a population sample is potential population substructure due to the existence of dog breeds. Indeed, although generally mtDNA does not allow dogs to be grouped into their respective breeds (

Obviously, the over- and underrepresentation of particular breeds in a population sample compared to the population from which the sample is drawn, may bias haplotype frequency estimates (

Against this background,

Some authors have indicated that population studies specific for single breeds may be forensically relevant in the rare event that the breed of the dog that donated the crime scene trace is known, for example by eye-witness reports (

Including pedigree data can improve intra-breed mtDNA diversity studies. In theory, an appropriate selection of representative individuals from existing maternal lines from pedigrees allows to capture all mtDNA haplotypes of a breed within a population while minimizing the amount of laboratory work. The frequencies of these haplotypes can be estimated from the numbers of offspring in each maternal line in the breed population (

Analyzing the haplotype frequency distribution within breeds can also give insight into differences between published population studies.An example of the impact of breed associated sample bias was given by

To evaluate the significance of a haplotype match between a dog trace and its suspected donor, a population sample should reliably reflect the population to which the donor of the trace is supposed to belong. As such, one might wonder about the importance of the geographic origin of the sampled dogs in a sampling strategy.

Probably the most important macrogeographic issue to consider in dog studies, is the fact that dog populations in Southeast Asia show almost the entire dog mtDNA diversity, while elsewhere in the world only parts of this diversity is present (

The description of haplotypes is a source of error and confusion when comparing population studies. Typically, haplotypes are aligned to a reference sequence using software supplemented with annotation rules in order to record them unambiguously as an alpha-numeric code. This code is a shortened annotation of the sequence string, consisting of differences to the reference sequence. For example, the HV-I alpha-numeric code of haplotype A11 is 15639A, 15814T and 16025C (

Illustration of different annotations for the HV-II polyC-polyT-polyC haplotype with 6 C’s, 8 T’s and 2 C’s. Annotation (1) was used by

| #C#T#C | 16661 | 16662 | 16663 | 16663.1 | 16663.2 | 16663.3 | 16664 | 16665 | 16666 | 16667 | 16668 | 16669 | 16670 | 16671 | 16672 | 16673 | 16674 |

| 3C8T3C | C | C | C | - | - | - | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | C | C | C |

| 6C8T2C (1) | C | C | C | C | C | - | C | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | C | C |

| 6C8T2C (2) | C | C | C | C | C | C | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | C | C | - |

Haplotypes can also be denoted by names. However, it is not good practice to provide only haplotype names in publications, like e.g.

Mistakes occur relatively often while copying and editing sequence data. Therefore, guidelines have been published to minimize making these clerical errors and to detect them more easily (

As more mtGenome data are generated, coding regions SNPs are encountered that appear to be characteristic for particular control region haplotypes and haplogroups (Verscheure, unpublished data). Such SNPs can help to indicate potential sequence or clerical errors. For example, the control region sequence of mtGenome haplotype A169* (A11 after removal of the deletion at 15932) belongs to haplogroup A (

As shown above, deposition of sequence data in GenBank provides an opportunity to verify sequence data quality. Unfortunately, in contrast to good practice, 15 of the 58 studies reviewed here did not submit any sequence to GenBank, but only provided alpha-numeric codes or haplotype names. Moreover, several papers did not even disclose the haplotype sequences or their estimated population frequencies (Table 1). When studies did deposit sequences in GenBank, they did so either only for new haplotypes, for all observed haplotypes, or for all sampled dogs. These various practices may confound subsequent analyses. For example,

Dog mtDNA studies show a large variety of analysis methods as well. Consequently, the quality of these analyses might vary. Next to annotation issues, several sequence quality issues have been observed while reviewing dog mtDNA studies. For example,

Thus, caution and proofreading is necessary for both new sequences and those extracted from papers and databases. Therefore,

The majority of dogs have haplotypes that are frequent in most dog populations worldwide. As a result, even if there are many rare haplotypes, the discriminatory power of the dog mtDNA control region is limited (

Evidently, expanding the length of the surveyed sequence will increase the number of polymorphic sites and thus may improve the discriminatory power of the mtDNA control region in dogs. However, most population studies did not include HV-II and as such missed important variation that often allows splitting up HV-I haplotypes. Hence, sequencing at least both HV-I and HV-II is recommended for forensic population studies (

A number of complete control region haplotypes still show high population frequencies. Therefore, it is advised to further increase the discriminatory power of dog mtDNA by surveying population samples for entire mtGenomes (

Not every forensic laboratory has the resources to conduct large-scale population studies. As such, supplementing smaller, local samples with published data allows capturing more mtDNA variability. However, this practice may bias the haplotype frequency distribution in the pooled sample compared to the population of interest, because of (1) sample heterogeneity, (2) inconsistent sequence quality, (3) clerical errors and (4) the difficulty of sequence comparisons due to variation in sequence lengths, alignment procedures, and sequence annotation. Relying on a public dog mtDNA database instead of, or in addition to, published local population data may be a trustworthy alternative, provided that the sequences are carefully reviewed before inclusion in the database. As such, submitting population sample data to the database could be an obligatory quality check with which studies have to comply before they are published. This is often demanded for human mtDNA population data (

To establish a reliable dog mtDNA database, inspiration can be found in the European DNA profiling group (EDNAP) mtDNA population database (EMPOP) for human mtDNA haplotypes useful in forensic casework. EMPOP stresses the need for generating mtDNA sequence data of the highest quality (

Next to the need for high quality mtDNA population data from all around the world, three other important requirements for building a dog mtDNA database are discussed hereafter. Firstly, management by a central laboratory is indispensable to perform the quality assessment of submitted population samples, to maintain and update the database software and web portal, and to communicate about it to the users. After submission to EMPOP, this laboratory reviews the population sample data for errors by e.g. examining the raw sequence data and using quasi-median network analysis (

Secondly, the database should be searchable and provide tools for comparison of various mtDNA sequence ranges. EMPOP uses the SAM search engine, which translates the queried haplotype and all database entries into sequence strings that are more easily comparable than alpha-numeric codes. In this way, it avoids generating biased haplotype frequency estimates caused by alignment and annotation inconsistencies making that database entries remain undetected in a database search even if they are identical to the queried haplotype (

Finally, the database should sufficiently document background information on the specimens. This enables the selection of subsets of samples in the database relevant to a specific case, such as dogs from specific geographic regions, of particular breeds, etc. In casework, selection of a suitable dataset is vital to a correct evaluation of evidence. Weighing the evidence against several database subdivisions is recommended to consider which one provides the most appropriate and conservative estimate of a haplotype’s random match probability (

FidoSearchTM, a canine mtDNA database with search software, was developed for use in casework by the Institute of Pathology and Molecular Immunology in Porto, Portugal in collaboration with Mitotyping Technologies in Pennsylvania, USA (

In order to meet forensic quality standards, a dog mtDNA population sample needs to be representative of the population of interest to the case. To this end, several recommendations can be made for performing and publishing a dog mtDNA population study for forensic purposes: (1) provide sufficiently detailed information on the population of interest, the sampling strategy and the sampled dogs, (2) include at least several hundred dogs in the population sample, (3) intend to avoid biased inclusion of maternal relatives, (4) use a population sample reflecting the dog population where the crime occurred, (5) the composition of the population sample in terms of purebred and mixed-breed dogs, groups of breeds of a particular geographic origin, and dogs belonging to specific breeds, should be proportional to the studied population, (6) apply a high quality and validated analytical methodology and run quality control steps to minimize the risk of errors during either laboratory work or data processing, (7) submit the haplotype sequence strings to a publicly available database such as GenBank and (8) follow the

All things considered, this review emphasizes the need for more forensically relevant, high quality dog mtDNA population studies. In addition, it stresses the need for a publicly available dog mtDNA population database that assembles easily comparable and thoroughly checked population data from all around the world. Finally, expanding mtDNA studies from the control region to the entire mtGenome is recommended to enhance the discriminatory power of forensic dog mtDNA analysis.

S. Verscheure is a PhD student at the University of Antwerp supported by a grant from the Belgian Federal Public Planning Service Science Policy. This work was conducted within the framework of FWO Research Community W0.009.11N “Belgian Network for DNA Barcoding”.