(C) 2011 Robert L. Davidson. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

As part of an All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory in Boston Harbor Islands national park area, an inventory of carabid beetles on 13 islands was conducted. Intensive sampling on ten of the islands, using an assortment of passive traps and limited hand collecting, resulted in the capture of 6, 194 specimens, comprising 128 species. Among these species were seven new state records for Massachusetts (Acupalpus nanellus, Amara aulica, Amara bifrons, Apenes lucidulus, Bradycellus tantillus, Harpalus rubripes and Laemostenus terricola terricola—the last also a new country record; in passing we report also new state records for Harpalus rubripes from New York and Pennsylvania, Amara ovata from Pennsylvania, and the first mainland New York records for Asaphidion curtum). For most islands, there was a clear relationship between species richness and island area. Two islands, however, Calf and Grape, had far more species than their relatively small size would predict. Freshwater marshes on these islands, along with a suite of hygrophilous species, suggested that habitat diversity plays an important role in island species richness. Introduced species (18) comprised 14.0% of the total observed species richness, compared to 5.5% (17 out of 306 species) documented for Rhode Island. We surmise that the higher proportion of introduced species on the islands is, in part, due to a higher proportion of disturbed and open habitats as well as high rates of human traffic. We predict that more active sampling in specialized habitats would bring the total carabid fauna of the Boston Harbor Islands closer to that of Rhode Island or eastern Massachusetts in richness and composition; however, isolation, human disturbance and traffic, and limited habitat diversity all contribute to reducing the species pool on the islands relative to that on the mainland.

Carabidae, Boston Harbor Islands, biodiversity inventory, introduced species, state records Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, country record U. S.

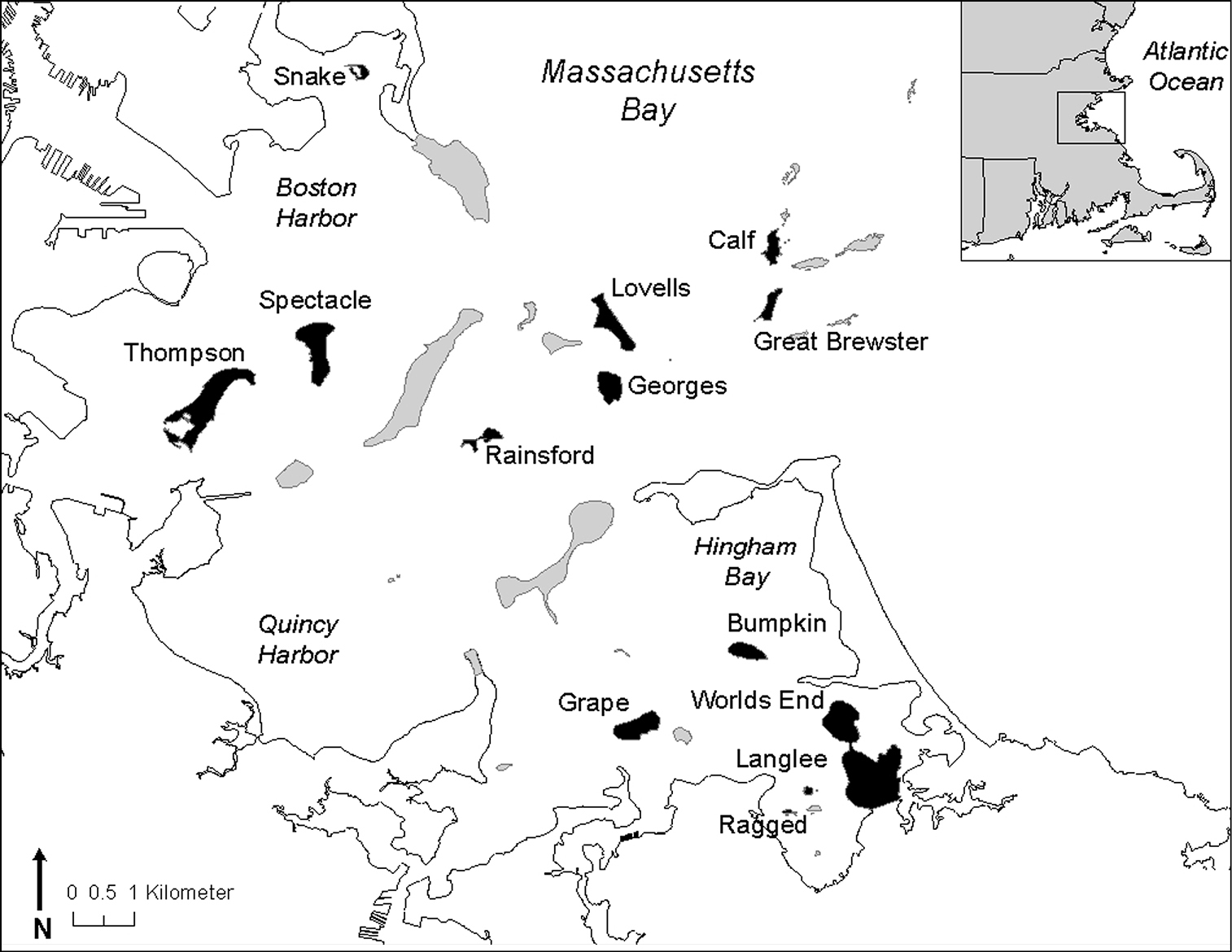

The Boston Harbor Islands national park area comprises 34 islands and peninsulas lying within 20 km of downtown Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. (Fig. 1). The islands have a long history of use and colonization by both Native and European Americans. Island landscapes have been altered over time with fishing settlements and agriculture, military forts and other institutional buildings, a landfill and sewage treatment plants, and by many other activities (

Figure 1. Location of Boston Harbor Islands national park area. Islands/peninsulas sampled for carabid beetles are shaded in black.

In an effort to learn more about its natural resources, the park initiated an All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory (ATBI) in 2005, with a primary objective cataloguing arthropod biodiversity across the islands. The ATBI concept, initially conceived by

Carabid beetles are a focal group of the ATBI because they are one of the most diverse and abundant beetle families on the islands, both in species and individuals; because they are relatively well known taxonomically and distributionally; and because there is expertise available for their identification. There is also enough information about them from the adjacent mainland to make cautious comparison possible, though unfortunately nothing as up to date as the current ATBI.

The objectives of this study are to: (1) inventory the carabid beetle fauna of a subset of islands (and one peninsula) in the park; (2) document their patterns of distribution across islands; (3) assess the regional significance of species occurrences in Boston Harbor and (4) compare the carabid fauna on the islands with that on the mainland of Rhode Island, including similarity of species composition, species richness, and the proportion of introduced species. We use the words introduced and introduction in this paper to refer to invasive species which arrived accidentally or incidentally, e.g., in ballast through human commerce, as opposed to deliberate introductions, e.g., as biological control agents.

MethodsSite description. The islands and one peninsula (World’s End) sampled for carabid beetles range in size from 1.1 to 104.5 ha (Table 1). The majority of the islands are drumlins, formed by deposits of glacial till in Boston basin; a few (Ragged, Langlee, Calf) are bedrock outcrops (

Almost all of the islands in the park are open to human visitors. Several islands (Bumpkin, Georges, Grape, Lovells, Spectacle, and Thompson) are serviced by public ferries between May and October. Portions of these islands and World’s End are also actively landscaped (e.g., mowing, clearing brush). Islands with ferry service and World's End receive hundreds to tens of thousands of visitors per year (Table 1), with Spectacle and Georges Islands serving as hubs in the ferry system. Thompson Island, an education center, also receives very high numbers of visitors. The remaining islands, which do not have public ferry service, probably receive on the order of hundreds of visitors per year, but records are not available.

Field sampling design. Islands were sampled with varying intensities and in different years (Table 1). Three islands (Thompson, Grape, and Langlee) were sampled between August and October, 2005, in a short pilot season to test field sampling methods. A full-season (May through October) structured sampling design was implemented on Grape and Thompson in subsequent years, and also on seven other islands (Table 1). Three additional islands (Georges, Lovells, and Rainsford) were visited sporadically for hand-collecting only.

On islands with structured sampling, a variety of traps and methods was used to sample different habitats. Sampling was stratified by dominant habitat types: forest, shrubland, meadow, beach (above the high tide line), salt- or brackish marsh, freshwater marsh or pond edge. Larger islands had more sampling sites than smaller islands, but had fewer samples per unit area overall. Sampling methods included: pitfall traps (plastic cups dug into the ground, 90 mm diameter at the mouth) in groups of three traps per site; litter samples run through Berlese funnels; malaise traps, one per island, rotated through different habitats over the season; mercury vapor and UV lights; and bowl traps laid out every 5 m in transects of 70 m, placed near flowering plants in open areas. Sampling generally occurred every other week, during which pitfall and malaise traps were open for the full week; light traps were run one night in different locations on each island; and bowls were set up and opened for several hours on one sunny day. In addition to the structured passive sampling, active sampling (e.g., hand-collecting, sweep nets, beating sheets) occurred on all visits to the islands. Thompson Island, an outdoor education center, contributed many specimens via hand collections and pitfall samples from student programs.

Carabid beetles were identified to species in part using (

Data analysis. To estimate the absolute (versus observed) number of species on the islands sampled, we used the Chao 1 species richness estimator (

SChao 1 = Sobs + F1 2/2F2

where Sobs is the number of observed species in the sample, and F1 and F2 are the number of observed species represented by one and two individual(s), respectively. We used the program EstimateS 8.2 for these calculations (

Area, isolation, human visitation rates, and sampling design for each island sampled in Boston Harbor Island national park area.

| Island | Code | Terrestrial | Isolation | Human | Year(s) | Sampling effort: # sites (# samples) | ||||

| area (ha) | (km) | visitation3 | sampled4 | Pitfall | Litter | Malaise | Light | Bowl | ||

| Bumpkin¹ | BM | 12.2 | 627 | 933 | 2006 | 5 (21) | 0 | 3 (5) | 3 (3) | 0 |

| Calf | CF | 7.5 | 3268 | NA | 2007 | 5 (39) | 7 (9) | 2 (6) | 1 (1) | 4 (7) |

| Georges | GE | 15.8 | 1453 | 67, 655 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Grape | GP | 21.9 | 456 | 808 | 2005, 2008 | 13 (55) | 12 (30) | 8 (9) | 4 (6) | 19 (29) |

| Great Brewster | GB | 7.5 | 2339 | NA | 2006 | 6 (45) | 11 (15) | 3 (7) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Langlee | LN | 1.8 | 492 | NA | 2005 | 5 (25) | 5 (20) | 3 (10) | 5 (20) | 0 |

| Lovells | LV | 19.6 | 2177 | 5, 576 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 3 (3) | 7 (7) | |

| Rainsford | RF | 6.6 | 2390 | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ragged | RG | 1.1 | 320 | NA | 2006 | 5 (31) | 12 (20) | 2 (6) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Snake | SN | 2.9 | 344 | NA | 2007 | 4 (20) | 4 (6) | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Spectacle | SP | 34.6 | 1907 | 35, 441 | 2007 | 5 (39) | 3 (12) | 4 (7) | 1 (1) | 12 (12) |

| Thompson¹ | TH | 54.2 | 517 | 17, 621 | 2005, 2007 | 31 (119) | 16 (36) | 10 (27) | 13 (8) | 13 (15) |

| World’s End² | WE | 104.5 | 0 | 49, 664 | 2006 | 9 (63) | 13 (21) | 7 (13) | 8 (7) | 16 (22) |

1 Island connected to mainland at very low tides.

2 Peninsula, connected to mainland at all times.

3 Visitor counts for 2007. Counts for all islands represent ferry passengers only (visitors in private boats not included), and count for WE represents drive-up visitors. NA = no available data/no ferry service. (National Park Service 2010, Boston Harbor Island visitor statistics, unpublished report).

4 Years for structured sampling, does not include all hand-collecting events. 2005 sampled Aug-Oct only.

We collected a total of 6, 194 carabid specimens, comprising 128 species (Table 2). Seven species were recorded from Massachusetts for the first time, and one of these, Laemostenus terricola, was also a new record for the U.S. (see accounts below). The six most abundant species (Harpalus rufipes, Amara bifrons, Pterostichus mutus, Carabus nemoralis, Poecilus lucublandus and Synuchus impunctatus) made up 59.4% of the total catch. Thirty-five species were represented by a single specimen, and 67 species (over half the total) were represented by five or fewer specimens. The high proportion of singletons and doubletons contributed to an estimated absolute species richness of 189 species (95% CI: 155, 269). Introduced species (18) comprised 14.0% of the total observed species richness, and 45.5% of total specimen abundance. Three of the six most abundant carabid species overall were introduced.

The distribution of carabids across islands varied greatly by species. The most widespread species, the abundant Poecilus lucublandus, was collected on ten islands. However, there was no clear relationship between total abundance of a species and its distribution across multiple islands. For instance, Amara bifrons was the second most abundant species overall (822) but occurred on only 3 islands, with 815 individuals on Spectacle Island alone. In contrast, we collected Harpalus rubripes on six islands, but the total catch comprised only ten specimens. Six of the introduced species each occurred on six or more islands.

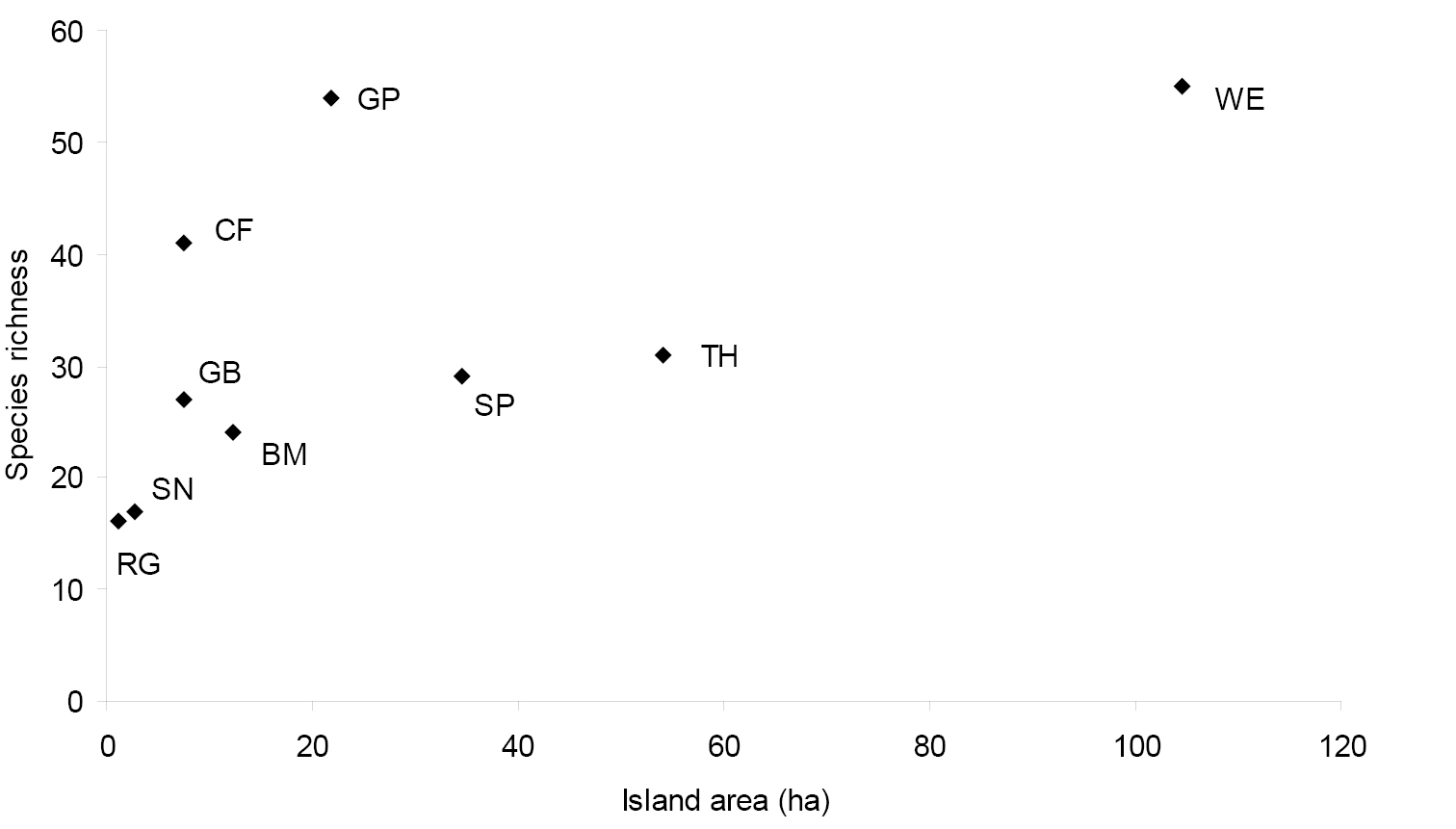

Among islands that were sampled intensively for at least one full season (Table 1), species richness varied between 16 (Ragged Island) and 63 species (Grape Island). While there was a clear relationship between island area and species richness for seven of the intensively sampled islands (Fig. 2), Grape Island and Calf Island were obvious outliers as each had many more species than expected for its size.

Carabid specimens collected on islands in Boston Harbor Islands national park area 2005-2009. See Table 1 for island abbreviations.

| Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Status† | BM | CF | GE | GP | GB | LN | LV | RG | RF | SN | SP | TH | WE | Spec. | Islands |

| Acupalpus (Acupalpus) carus (LeConte) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| *Acupalpus (Acupalpus) hydropicus (LeConte) | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| *Acupalpus (Acupalpus) nanellus Casey | S | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Acupalpus (Tachistodes) partiarius (Say) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Acupalpus (Acupalpus) pumilus Lindroth | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| *Acupalpus (Philodes) rectangulus Chaudoir | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Agonum (Olisares) aeruginosum Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Agonum (Olisares) decorum (Say) | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| *Agonum (Olisares) ferreum Haldeman | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Agonum (Olisares) fidele Casey | 15 | 15 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Agonum (Europhilus) gratiosum (Mannerheim) | 31 | 11 | 3 | 45 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Agonum (Olisares) melanarium Dejean | 57 | 187 | 8 | 252 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Agonum (Agonum) muelleri (Herbst) | I | 4 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 17 | 4 | |||||||||

| Agonum (Europhilus) palustre Goulet | 2 | 9 | 11 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| *Agonum (Olisares) punctiforme (Say) | 5 | 5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Agonum (Europhilus) retractum LeConte | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Agonum (Olisares) tenue (LeConte) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Agonum (Europhilus) thoreyi Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Amara (Amara) aenea (DeGeer) | I | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Amara (Zezea) angustata (Say) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Amara (Bradytus) apricaria (Paykull) | I | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| *Amara (Curtonotus) aulica (Panzer) | I, S | 1 | 6 | 7 | 22 | 30 | 15 | 81 | 6 | |||||||

| Amara (Bradytus) avida (Say) | 6 | 6 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| *Amara (Celia) bifrons (Gyllenhal) | I, S | 3 | 815 | 4 | 822 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Amara (Amara) cupreolata Putzeys | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| *Amara (Bradytus) exarata Dejean | 30 | 1 | 49 | 7 | 9 | 96 | 5 | |||||||||

| Amara (Amara) familiaris (Duftschmid) | I | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Amara (Amara) littoralis Mannerheim | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Amara (Amara) lunicollis Schiødte | 3 | 21 | 3 | 3 | 30 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Amara (Celia) musculis (Say) | 1 | 3 | 14 | 1 | 8 | 20 | 47 | 6 | ||||||||

| *Amara (Amara) ovata (Fabricius) | I | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Amara (Paracelia) quenseli (Schönherr) | 1 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 57 | 74 | 5 | |||||||||

| Amara (Celia) rubrica Haldeman | 16 | 4 | 20 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Amphasia (Pseudamphasia) sericea (T.W. Harris) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Anisodactylus (Anisodactylus) harrisii LeConte | 5 | 13 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 19 | 7 | 22 | 79 | 9 | |||||

| Anisodactylus (Anisodactylus) nigerrimus (Dejean) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Anisodactylus (Anisodactylus) nigrita Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Anisodactylus (Gynandrotarsus) rusticus (Say) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 4 | ||||||||||

| *Apenes lucidulus (Dejean) | S | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Apristus latens (LeConte) | 2 | 30 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 60 | 106 | 7 | |||||||

| Apristus subsulcatus (Dejean) | 8 | 33 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 247 | 296 | 6 | ||||||||

| *Asaphidion curtum (Heyden) | I | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Atranus pubescens (Dejean) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Axinopalpus biplagiatus (Dejean) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Badister (Badister) notatus Haldeman | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Badister (Trimorphus) transversus Casey | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Bembidion (Ochthedromus) americanum Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Bembidion (Notaphus) constrictum (LeConte) | 1 | 10 | 11 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Bembidion (Notaphus) contractum Say | 4 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Bembidion (Trepanedoris) frontale (LeConte) | 1 | 18 | 4 | 23 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Bembidion (Eupetedromus) graciliforme Hayward | 1 | 9 | 2 | 12 | 3 | |||||||||||

| *Bembidion (Lymnaeum) nigropiceum (Marsham) | I | 1 | 9 | 72 | 82 | 3 | ||||||||||

| *Brachinus (Neobrachinus) vulcanoides Erwin | 38 | 38 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Bradycellus (Stenocellus) rupestris (Say) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||

| *Bradycellus (Stenocellus) tantillus (Dejean) | S | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Calathus (Neocalathus) opaculus LeConte | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Carabus (Archicarabus) nemoralis O. F. Müller | I | 3 | 13 | 69 | 174 | 14 | 187 | 23 | 483 | 7 | ||||||

| Chlaenius (Anomoglossus) emarginatus Say | 1 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 26 | 6 | ||||||||

| Chlaenius (Chlaeniellus) impunctifrons Say | 7 | 7 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Chlaenius (Chlaeniellus) pennsylvanicus pennsylvanicus Say | 21 | 21 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Chlaenius (Chlaeniellus) tricolor tricolor Dejean | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 5 | |||||||||

| Cicindela (Cicindela) sexguttata Fabricius | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Clivina (Clivina) fossor (Linnaeus) | I | 5 | 5 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Colliuris (Cosnania) pensylvanica (Linnaeus) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| *Cymindis (Cymindis) americana Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Cymindis (Pinocodera) limbata Dejean | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Cymindis (Cymindis) neglecta Haldeman | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Cymindis (Cymindis) pilosa Say | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| *Cymindis (Pinacodera) platicollis (Say) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 13 | 5 | |||||||||

| Dicaelus (Paradicaelus) dilatatus dilatatus Say | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Dicaelus (Paradicaelus) elongatus Bonelli | 13 | 7 | 4 | 26 | 23 | 73 | 5 | |||||||||

| *Dicaelus (Paradicaelus) politus Dejean | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Diplocheila (Isorembus) obtusa (LeConte) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5 | |||||||||

| Dromius (Dromius) piceus Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Dyschirius (Dyschiriodes) dejeanii Putzeys (=integer LeConte) | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Dyschirius (Dyschiriodes) globulosus (Say) | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Dyschirius (Dyschiriodes) setosus LeConte | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Elaphropus incurvus (Say) | 23 | 3 | 1 | 27 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Elaphropus vernicatus (Casey) | 5 | 5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Elaphropus xanthopus (Dejean) | 6 | 1 | 7 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Harpalus (Harpalus) affinis (Schrank) | I | 10 | 1 | 3 | 16 | 2 | 32 | 5 | ||||||||

| Harpalus (Megapangus) caliginosus (Fabricius) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Harpalus (Pseudoophonus) compar LeConte | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Harpalus (Pseudoophonus) erythropus Dejean | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Harpalus (Harpalus) opacipennis (Haldeman) | 4 | 1 | 33 | 1 | 39 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Harpalus (Pseudoophonus) pensylvanicus (DeGeer) | 43 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 19 | 6 | 88 | 8 | ||||||

| *Harpalus (Harpalus) rubripes (Duftschmid) | I, S | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 6 | |||||||

| Harpalus (Pseudoophonus) rufipes (DeGeer) | I | 5 | 95 | 184 | 82 | 38 | 537 | 12 | 57 | 1010 | 8 | |||||

| Harpalus (Harpalus) somnulentus Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| *Laemostenus (Pristonychus) terricola terricola (Herbst) | I, C | 3 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| *Lebia (Lebia) analis Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| *Lebia (Loxopeza) grandis Hentz | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Lebia (Lebia) pumila Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Lebia (Lebia) solea Hentz | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| *Lebia (Lebia) viridipennis Dejean | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Lebia (Lebia) viridis Say | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Notiobia (Anisotarsus) terminata (Say) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Notiophilus aeneus (Herbst) | 5 | 11 | 16 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Ophonus (Metophonus) puncticeps Stephens | I | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 39 | 6 | 51 | 6 | |||||||

| Oxypselaphus pusillus (LeConte) | 2 | 18 | 1 | 2 | 23 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Patrobus (Neopatrobus) longicornis (Say) | 1 | 7 | 8 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Perigona (Perigona) nigriceps (Dejean) | I | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Platynus (Platynus) decentis (Say) | 56 | 2 | 1 | 59 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Poecilus (Poecilus) chalcites (Say) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Poecilus (Poecilus) lucublandus (Say) | 42 | 22 | 126 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 92 | 331 | 10 | ||||

| Pterostichus (Lamenius) caudicalis (Say) | 6 | 15 | 21 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Pterostichus (Melanius) corvinus (Dejean) | 50 | 50 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Pterostichus (Phonias) femoralis (Kirby) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Pterostichus (Pseudomaseus) luctuosus (Dejean) | 7 | 70 | 1 | 78 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Pterostichus (Morphnosoma) melanarius (Illiger) | I | 6 | 92 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 61 | 3 | 178 | 7 | ||||||

| Pterostichus (Bothriopterus) mutus (Say) | 10 | 2 | 212 | 12 | 34 | 50 | 1 | 321 | 82 | 724 | 9 | |||||

| Pterostichus (Phonias) patruelis (Dejean) | 26 | 26 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Pterostichus (Bothriopterus) pensylvanicus LeConte | 5 | 11 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 33 | 6 | ||||||||

| Pterostichus (Hypherpes) tristis (Dejean) | 1 | 9 | 10 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| *Scarites (Scarites) subterraneus Fabricius | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| *Selenophorus hylacis (Say) | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Selenophorus opalinus (LeConte) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Sphaeroderus stenostomus lecontei Dejean | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Stenolophus (Agonoderus) comma (Fabricius) | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Stenolophus (Agonoleptus) conjunctus (Say) | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Stenolophus (Agonoderus) lineola (Fabricius) | 4 | 2 | 6 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Stenolophus (Stenolophus) ochropezus (Say) | 2 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 45 | 7 | |||||||

| Stenolophus (Agonoleptus) rotundicollis (Haldeman) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Syntomus americanus (Dejean) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Synuchus (Pristodactyla) impunctatus (Say) | 4 | 46 | 7 | 184 | 49 | 24 | 314 | 6 | ||||||||

| Tachyta angulata Casey | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| *Trichotichnus (Trichotichnus) autumnalis (Say) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Xestonotus lugubris (Dejean) | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Total no. specimens per island | 153 | 395 | 38 | 1418 | 366 | 240 | 28 | 107 | 13 | 108 | 1606 | 1220 | 502 | |||

| Total no. species per island | 24 | 41 | 2 | 63 | 27 | 11 | 9 | 16 | 4 | 17 | 29 | 48 | 55 | |||

* Species of special interest, individual species accounts in text.

† Status: I = introduced; S = state record; C = country recordTable 2. Carabid specimens collected on islands in Boston Harbor Islands national park area 2005-2009. See Table 1 for island abbreviations.

Accounts of species of special interest

Remarks on habitat and biology are based on the personal experience of one of the authors (Davidson) and the very fine natural history of North American ground beetles by

Specimens from New Hampshire and Massachusetts seem to be the most eastern and northern records for this species to date.

This is a State Record for Massachusetts, though not a surprising one as the species is now known from all New England states (recorded from Rhode Island in

Massachusetts specimens seem to represent the eastern end of the range of this species as far as now known, the nearest localities being in Vermont and Québec. It is not recorded from New Hampshire, Maine or northeastern Canada (

Specimens from New Hampshire and Massachusetts seem to be the most eastern records for this species to date. It is not recorded from Maine and is not known from Canada east of Ontario (

Specimens from New Hampshire and Massachusetts seem to be the most eastern records for this species to date. It is not recorded from Maine and is not known from Canada east of Ontario (

This introduced species is a State Record for Massachusetts. It appears to have been introduced in North America sometime before 1929 (

Much like the previous species (Amara aulica), this introduced species is a State Record for Massachusetts, also presumably introduced in northeast Canada before 1929 (

This is another species which seems to reach its eastern and northern limits in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. It is not yet recorded from Vermont or Maine (

Like many European carabids, this species has been spreading from introduction points in both the northeast and the northwest.

This is a State Record for Massachusetts and the northeast limit of the known range of this species. It is recorded from as far north and east as New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island and now Massachusetts, but it is not known from Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine or Canada (

This introduced species was reported from North America first by

The rediscovery of this species in Massachusetts is of sufficient significance to warrant a separate publication (see Davidson and Rykken, this volume).

This species seems to be relatively rare in collections and limited to coastal habitats, though nothing seems to be known about its habitat requirements. This species reaches its northern limit in Massachusetts and New Hampshire;

The Massachusetts specimen represents a State Record for this species. In New England, this species was known previously from Vermont, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Maine (

Specimens from Massachusetts and New Hampshire seem to represent the most northern and eastern records for this species. Québec records are from further west (

The distributional situation is probably similar to Cymindis americana. The species was not recorded from Québec in

The first report of this European species in North America was

This is apparently the first record of this species from the United States. Laemostenus terricola is known from both coasts of Canada: British Columbia in the northwest (

One should be aware that there is another, superficially similar Laemostenus that is now more or less cosmopolitan, originating from Europe and North Africa, but has reached ports in mid-Atlantic Islands, California, Washington, British Columbia, Peru, Chile, South Africa, Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand. It has not yet been reported from the east coast of North America but should be looked for, and one should not assume that a large Laemostenus from the east coast is necessarily Laemostenus terricola. This other species, Laemostenus (Laemostenus) complanatus (Dejean), is similarly synanthropic, but is fully winged and presumably capable of flight, and spreads relatively rapidly once colonized.

Specimens from Massachusetts may represent the most eastern and northern records for this species. In Canada it is known only from (presumably southern) Ontario (

Specimens from Massachusetts and New Hampshire represent the most eastern and (so far) most northeastern records for this species in the northeast.

Specimens from Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine represent the most eastern and northern records for this species. It is recorded from Québec (

Specimens from Massachusetts and New Hampshire represent the most eastern and northern records for this species to date. It is not reported from Maine (

Specimens from Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine represent the most eastern and northern records for this species to date. It has only recently been reported from Maine (without further locality,

Specimens from Massachusetts and Maine represent the most eastern and northeastern records for this species in the northeast.

Specimens from Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine represent the most eastern and northern records for this species in the northeast. It is recorded from Québec (

Inherent in any large-scale, multi-taxa inventory are trade-offs between sampling for maximum diversity (involving specialized active techniques for individual taxa) and sampling with maximum efficiency (prioritizing passive “broad spectrum” sampling techniques such as pitfall traps). Our final total of 128 carabid species on the islands, including seven new state records and one new country record, is high relative to other beetle families sampled in the ATBI, but there are undoubtedly many more carabid species to be found in specialized habitats or by using specialized collecting techniques. Our estimate of absolute species richness on the islands is at least 189 species, based on the 47 species of which we collected only one or two specimens.

Comparisons with the adjacent mainland carabid fauna are necessarily speculative, as there is no comparable recent survey. We chose Sikes’ checklist of Rhode Island Carabidae (2004) as the most complete and comparable reference, recording 306 species. Our comparisons, therefore, of introduced versus native species, and full-winged versus short-winged species, are based on 128 species known so far from the islands and 306 species known so far from Rhode Island, 111 of which are shared between both locations.

Of 128 species on the islands, 14.0% are introduced (18 species), more than twice the percentage of introductions in Rhode Island (17 species, 5.5%), a striking difference. We note that for three of the four introduced species in Boston Harbor that are not recorded in mainland Massachusetts or Rhode Island (Amara aulica, Amara bifrons and Laemostenus terricola) we cannot distinguish whether they are isolated, relatively new introductions limited to the islands, or whether they have spread, undetected, continuously along the coast from other introduction points. Despite the uncertainty regarding the true distribution of these three species, the relatively high proportion of introduced species in Boston Harbor remains noteworthy. The difference may be explained, in part, by the higher proportion of disturbed open dry habitats on the islands, with very little fresh water, as opposed to the greater diversity of older, established habitats (particularly wetlands and fresh water) in Rhode Island. But it is also possible that human traffic and commerce in the islands fosters more frequent introductions, or that these are more likely to become established because of the generally disturbed and depauperate biotic communities present, or a combination of these two. In some cases the islands may even be the point of introduction. This seems undoubtedly the case for the fourth introduced species not known from mainland Massachusetts or Rhode Island, Bembidion nigropiceum, as it is not yet known from anywhere else in North America. There is an overall pattern of a high percentage of introduced species recorded in this ATBI relative to the Rhode Island list. For example, the percentage of introduced curculionid beetles in Boston Harbor is 35.4%, compared to 21.4% in Rhode Island (

Dispersal ability is an important factor to consider for the colonization of islands in Boston Harbor. The percentages of macropterous (fully winged), wing dimorphic, and brachypterous (short-winged) species were similar for the islands and the mainland. Brachypterous species made up 7.8% of the fauna in both Rhode Island and on the Boston Harbor Islands, while wing dimorphic species made up 11.1% of the total on the mainland versus 14.8% on the islands. The identical rates of brachyptery are surprising, as one would expect isolated islands to have a smaller percentage of short-winged species than the mainland. The percentages of wing dimorphic species cannot be readily interpreted as we did not check the wing status of all individuals of wing dimorphic species. Native short-winged species may have been present already some 15, 000 years ago when the islands became isolated post-glaciation. But introduced short-winged species must have arrived on the islands in the last few hundred years. Three of the ten brachypterous species are introductions (Bembidion nigropiceum, Carabus nemoralis and Laemostenus terricola), as are two of the dimorphic species (Clivina fossor and Pterostichus melanarius). Carabus nemoralis was one of the most widespread species, present on seven of the nine islands we sampled intensively. This suggests a high incidence of passive transportation, possibly by human commerce and other human activity.

As is commonly the case with carabid surveys, a few species dominated the catch. The six most abundant species (Table 2), numbering over 300 specimens each, are all associated with open, dry areas and/or heavily disturbed areas. Three of them (Harpalus rufipes, Amara bifrons and Carabus nemoralis) are introduced species. Carabus nemoralis is brachypterous; Synuchus impunctatus is wing dimorphic; the rest are fully winged and capable of flight. The two fully winged introductions are still limited to the northeast; Harpalus rufipes is very abundant from Newfoundland to Connecticut, while the nearest recorded mainland populations of Amara bifrons are in New Hampshire (no specific locality). The third introduction, Carabus nemoralis, is now transcontinental in southern Canada and northern United States, having spread from introduction points near Vancouver and Newfoundland since the earliest recorded specimen (1890,

Freshwater is a scarce resource on the Boston Harbor Islands, and the remarkably high species richness on two islands (Calf and Grape; Fig. 2) with freshwater marshes or seeps, attests to the importance of habitat diversity for predicting species richness on an island. Most of the truly hygrophilous species were taken only on Calf and Grape islands, including Pterostichus corvinus, Pterostichus patruelis, Pterostichus caudicalis, several Agonum species, most of the Acupalpus species, Pterostichus luctuosus, and Agonum melanarium (the latter two species were also found on World’s End peninsula). Grape Island had the highest species richness of any of the islands, despite its relatively small size, and 26 of the 63 species collected there are associated with fresh water. Calf Island ranked fourth in species richness, with 41 species, in spite of its small size and distance from the mainland. Another hygrophilous species, Brachinus vulcanoides, was found only at World’s End, at a single site near a salt marsh. This species may have some salt tolerance, as the species is known so far only from coastal localities.

Figure 2. Relationship between island area and species richness of carabid beetles in Boston Harbor Islands national park area. Value for species richness has been standardized across all islands to include only one full season of sampling.

The cultural history of an island may also strongly influence species diversity. On Spectacle Island, a recently reclaimed landfill replanted within the last ten years, we collected 29 species and over 1, 606 individuals, more carabids than on any other island. This high abundance is due to the dominance of two species, Amara bifrons (815) and Harpalus rufipes (537), both introduced species and very active colonizers. While a few individuals of Amara bifrons were collected on two other islands, on Spectacle Island this species was taken at all five pitfall sites in different habitats. This suggests that Spectacle Island has been invaded relatively recently by this species and is undergoing active and aggressive colonization. The other species, Harpalus rufipes, has undoubtedly been in the area much longer, as it has reached seven islands and World’s End peninsula, but over half of the specimens were taken on Spectacle Island. This suggests it has been on Spectacle longer than on the other islands, and it too is actively and aggressively colonizing the island. It may also be that Spectacle has been the jumping off point for invasion of the islands for both species, Harpalus rufipes first, and now Amara bifrons.

ConclusionOn islands so variable in cultural history and habitat diversity, and with distances between islands small enough that opportunistic colonization may be commonplace, the classic predictors of species richness proposed by the theory of island biogeography (

We are indebted to the staff at Boston Harbor Islands national park area who facilitated our research on the islands, and the University of Massachusetts Boston Marine Operations staff who transported us to the islands. Students, interns, and volunteers too numerous to name individually here assisted us with field collections, specimen processing and data entry. Stephanie Madden devoted many undergraduate hours to specimen identification. Ross Bell was an inspiring mentor to all three authors in their formative years, and continues to inspire us with his lifelong passion for the natural world and remarkable knowledge of carabid beetles. We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Stone Foundation, the National Park Service in cooperation with the Boston Harbor Island Alliance, and the Green Fund.