(C) 2012 Juli Pujade-Villar. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

A new genus of cynipid oak gallwasp, Zapatella Pujade-Villar & Melika, gen. n. (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae: Cynipini), with two new species, Zapatella grahami Pujade-Villar & Melika, sp. n. and Zapatella nievesaldreyi Melika & Pujade-Villar, sp. n., is described from the Neotropics. Zapatella grahami, known only from the sexual generation, induces galls in acorns of Quercus costaricensis and is currently known only from Costa Rica. Zapatella nievesaldreyi, known only from the asexual generation, induces inconspicuous galls in twigs of Quercus humboldtii, and is known only from Colombia. Diagnostic characters for both new species are given in detail. Five Nearctic species are transferred from Callirhytis to Zapatella: Zapatella cryptica (Weld), comb. n., Zapatella herberti (Weld), comb. n., Zapatella oblata (Weld), comb. n., Zapatella quercusmedullae (Ashmead), comb. n., Zapatella quercusphellos (Osten Sacken), comb. n. (= Zapatella quercussimilis (Bassett), syn. n.). A key based on adults for the species belonging to Zapatella is also given. Generic limits and morphological characteristics of Zapatella and closely related genera are discussed.

Cynipini, Zapatella, Callirhytis, Colombia, Costa Rica, taxonomy, morphology, distribution, biology

The cynipid gallwasp fauna (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae) of the Neotropical region is very poorly known. Recently it was updated to include 6 tribes, 21 genera and 45 species, of which 41 are native and 4 have been introduced into the region; the native fauna includes 17 described species of oak gallwasps and 15 associated inquiline species (

The evaluation of the Neotropic gallwasp fauna cannot be done without a thorough examination of the Nearctic species, especially in the case of establishing new gallwasp genera. The current morphology-based taxonomy of the Nearctic Cynipini, with the last review of genera by

The validity of some Nearctic species of Callirhytis and there taxonomic position are discussed.

Material and methodsAdult gallwasps of an undescribed species were reared from acorn galls collected on Quercus costaricensis by the second author (PH) in Costa Rica; specimens belonging to yet another species were reared from galls collected on Quercus humboldtii by the first author (JPV) together with Claudia A. Medina and Miguel Torres in Colombia.

We follow the current terminology of morphological structures (

Digital images of wasp anatomy were produced with a digital Nikon Coolpix 4500 camera attached to a Leica DMLB compound microscope, followed by processing in CombineZP (Alan Hadley) and Adobe Photoshop 6.0 by the last author (GM). The SEM pictures were taken with a Stereoscan Leica-360 by Palmira Ros-Farré (Barcelona University, Spain) at a low voltage (15KV) and with gold coating; the forewing of Zapatella nievesaldreyi was taken by JPV with a digital camera Cannon SX-210-IS, attached directly to the ocular of a stereomicroscope. Gall images of Zapatella grahami were taken by P. Hanson; galls of Zapatella nievesaldreyi by the fourth author (M T).

The type material is deposited in the following institutions:

UB University of Barcelona, Spain (J. Pujade-Villar);

PDL Pest Diagnostic Laboratory (the former Systematic Parasitoid Laboratory, SPL), Tanakajd, Hungary (G. Melika);

MZUCR Museum of Zoology, University of Costa Rica, San Pedro Costa Rica (Paul Hanson);

IAvH Instituto Alexander von Humboldt, Villa de Leyva, Colombia (Claudia Medina).

Resultsurn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:D093C259-5DB1-43AE-A999-0AD53B8F4EA4

http://species-id.net/wiki/Zapatella

Figures 1 – 62Zapatella grahami Pujade-Villar & Melika, sp. n. by present designation.

Partially resembles Callirhytis, Bassettia and Plagiotrochus. However, in Zapatella, the malar sulcus is absent; mesosoma strongly arched, short, as long as high in lateral view; mesoscutum with numerous fine short, interrupted transverse striae with numerous longitudinal anastomosis connecting transverse striae and together forming a net-like, delicately reticulate, irregular sculpture; the pronotum laterally delicately reticulate; the metascutellum rugoso-reticulate; the metanotal trough and the lateral area of the propodeum with dense white setae. In Callirhytis a distinct malar sulcus is present; the mesosoma less arched, always at least slightly longer than high in lateral view; the transversely orientated rugae on the mesoscutum are much stronger with much fewer anastomoses between them; the pronotum with distinct strong rugae laterally; the metascutellum rugose, never reticulate; the metanotal trough and the lateral area of the propodeum without or with very few setae. In Bassettia the mesosoma is strongly compressed dorsolaterally, distinctly longer than broad; the head always more massive from above and nearly rounded in anterior view, broader than the mesosoma. In Plagiotrochus the sculpture of the mesopleuron, the shape of propodeal carinae and the length of the prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium are quite different. The most striking characters that differentiates Zapatella from the above-mentioned genera are the long prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium, which is 6.0–8.5 times longer than broad; hind coxae with dense white setae on the dorsoposterior surface, while in the other mentioned genera the prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium is very short, at most 2–3 times longer than broad, and hind coxae without dense setae. For more details see also the Discussion.

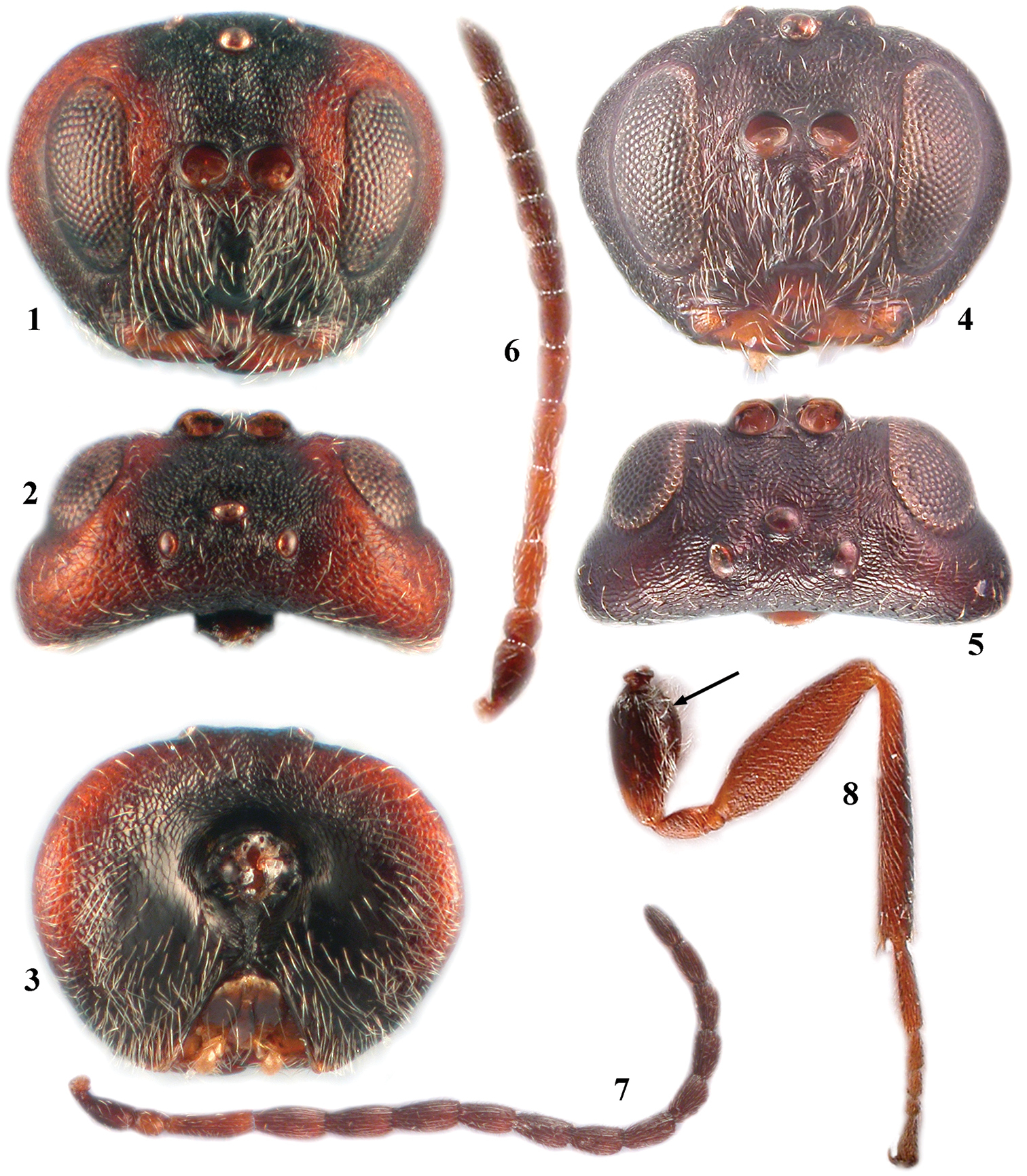

Zapatella grahami 1 head, female (anterior view) 2 head, female (dorsal view) 3 head, female (posterior view) 4 head, male (anterior view) 5 head, male (dorsal view) 6 antenna, female 7 antenna, male 8 hind leg, female (arrow indicates the dense white setae on dorsoposterior surface of coxa).

Body, including antennae and legs, predominantly chestnut brown; in some species head partially, mesoscutellum and stripes on mesoscutum dark brown to black. Head 1.3–1.5 times as broad as high in anterior view, massive from above and slightly broader than mesosoma. Gena broadened behind eye, as broad as transverse diameter of eye; malar sulcus absent. Antenna with 11 flagellomeres in female, 13 in male.

Mesosoma strongly arched, short, as long as high in lateral view. Pronotum delicately reticulate laterally; mesoscutum with numerous fine interrupted short transverse striae with numerous longitudinal anastomosis connecting transverse striae and together forming a net-like, delicately reticulate, irregular sculpture. Notauli complete (only in Zapatella herberti) or incomplete, extending to 1/2–2/3 length of mesoscutum, converging, deep and broad posteriorly [in some species, on first view, notauli seem to be complete; however, these are just darker lines, not impressed notauli, e.g. Zapatella quercusmedullae]. Anterior parallel lines extending to 1/2 length of mesoscutum; parapsidal lines distinct and broad, starting from posterior margin and extending to 1/2 length of mesoscutum; median mesoscutal line present or absent. Mesoscutellum 0.5 times as long as mesoscutum, as long as broad, not or only slightly overhanging metanotum, center of disk reticulate, sides and posterior 1/3–2/3 dull rugose; scutellar foveae present, indistinctly delimited posteriorly. Mesopleuron uniformly delicately reticulate, smooth and shiny basally. Metascutellum rugoso-reticulate; metanotal trough and lateral propodeal area with dense setae. Central propodeal area delimited by distinct subparallel or slightly bented outwards lateral propodeal carinae. Dorsoposterior surface of hind coxa with dense white setae. Tarsal claws simple, without basal lobe. Forewing venation pale yellow, indistinct, R1 inconspicuous, hardly traceable; wing margin without cilia. 2nd metasomal tergite with felt-like dense ring of white setae, interrupted dorsally and few setae scattered on lateral surface of tergite; narrow posterior band on 2nd metasomal tergite and all subsequent tergites with very delicate dense micropunctures. Prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium very long, 6.0–8.5 times longer than broad, with very few short white setae in two rows, directed ventrally; subapical setae absent.

Based on a word-play in football, a joke often used between some coauthors and prof. Graham N. Stone (Edinburgh University), in honour of whom one of the species is named.

Feminine.

According to the emergence dates of adults obtained from the collected galls, both sexual and asexual forms are present in the newly described genus. However, the emergence periods of alternate generations are overlapping. Moreover, no morphological differences have been observed between sexual and asexual females. The duration of life cycle is probably more than one year. In the Neotropical area the sexual form (Zapatella grahami Pujade-Villar & Melika, sp. n.)is obtained from acorn galls, while the asexual form (Zapatella nievesaldreyi Melika & Pujade-Villar, sp. n.) from twig galls; in the Nearctic area the asexual forms are obtained from twig and bud galls (Zapatella cryptica (Weld), comb. n., Zapatella herberti (Weld), comb. n., Zapatella quercusmedullae (Ashmead), comb. n.), Zapatella oblata (Weld), comb. n., while the sexual form, Zapatella quercusphellos (Osten Sacken) comb. n.(= quercussimilis (Bassett), syn. n. from twig galls. A detailed study of the biological cycles is necessary to solve this problem, which might be partially similar to that found in Plagiotrochus amenti Kieffer whichhas two reproductive modes: a heterogonic life cycle with alternation of generations in the circum-Mediterranean region, and an asexual, parthenogenetic life cycle in North America (

Currently known fromthe Neotropics(Costa Rica and Colombia) and the Nearctic (USA, from California, through Texas to Florida and along the Atlantic coast, up to New York state), after transferring 4 Callirhytis species.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:B802BBE3-E4BF-4971-9569-96266500DBE4

HOLOTYPE female (deposited in UB): “COSTA RICA, Cartago-Jose, Cerro de la Muerte, 3000 m, 2.X.1988. Col. Hanson” (white label), “Quercus costaricensis, fruit (acorn) galls” (white label), Holotype of Zapatella grahami ♀ Pujade-Villar & Melika n. gen & n. sp. design. JP-V 2012” (red label). PARATYPES (5 males and 20 females): 3 males and 14 females with the same data as the holotype and 1 male and 1 female with the similar data, only the collecting date is II.1988. 2 males and 10 females are deposited in UB, 1 male and 5 females in PDL, 1 male and 3 females in MZUCR, 1 male and 2 females USNM.

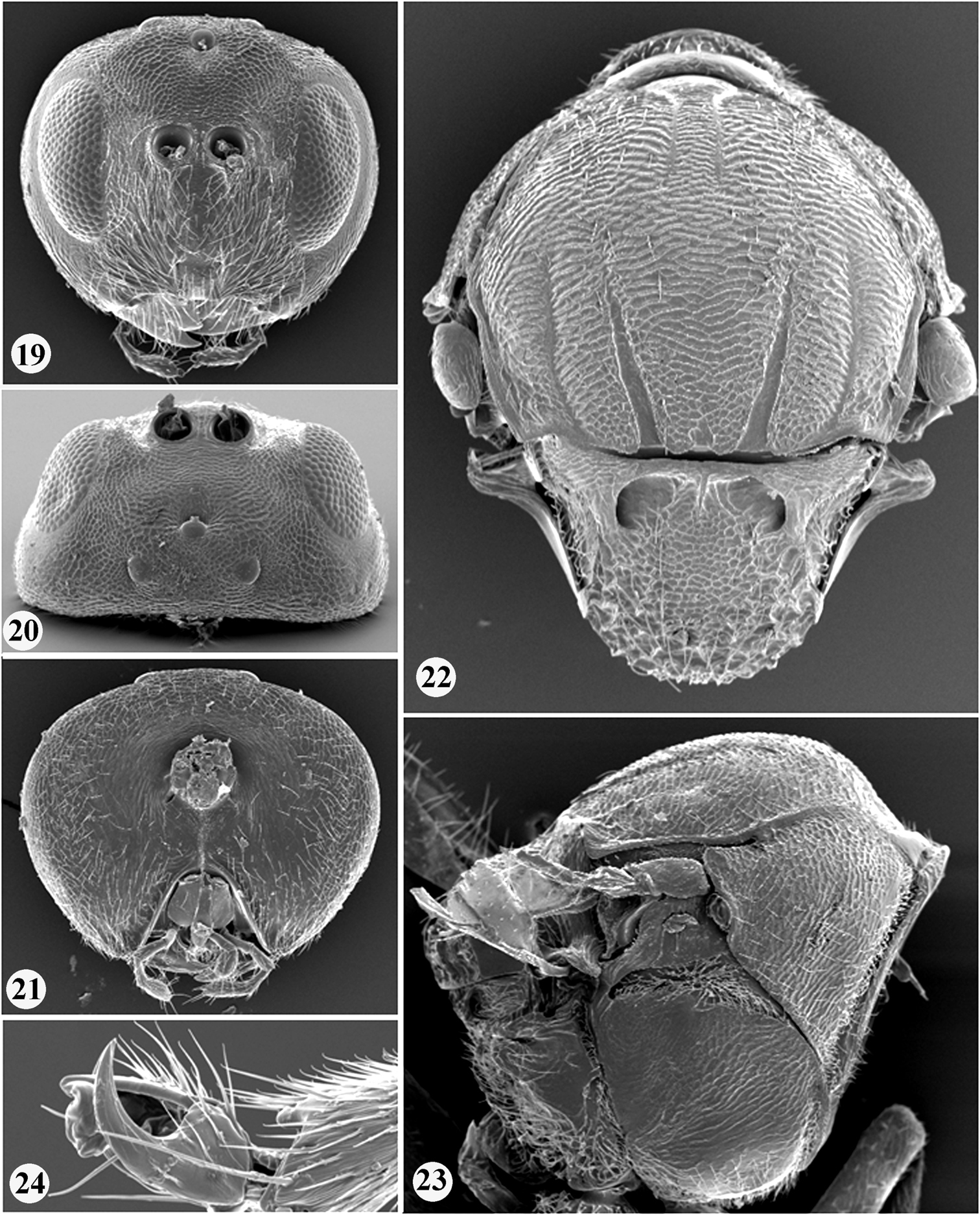

In Zapatella three species, Zapatella oblata, Zapatella grahami sp. n. and Zapatella nievesaldreyi sp. n., have the head and mesosoma partially dark brown to black. Zapatella oblata differs from the two other mentioned species by a very long median mesoscutal line which extending to 2/3 of the mesoscutum length, while in Zapatella grahami and Zapatella nievesaldreyi the median mesoscutal line is absent or present in a form of a very short triangle. In Zapatella grahami the females are much darker, POL 1.4 times as broad as OOL (Fig. 2), bottom of scutellar foveae with rugae (Fig. 11), and the prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium 7.5–8.5 times as long as broad (Figs 14, 16). In Zapatella nievesaldreyi the females are lighter, POL equal OOL (Fig. 20), bottom of scutellar foveae smooth and without rugae (Fig. 22), and the prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium 6.0–7.0 times as long as broad (Figs 28–29).

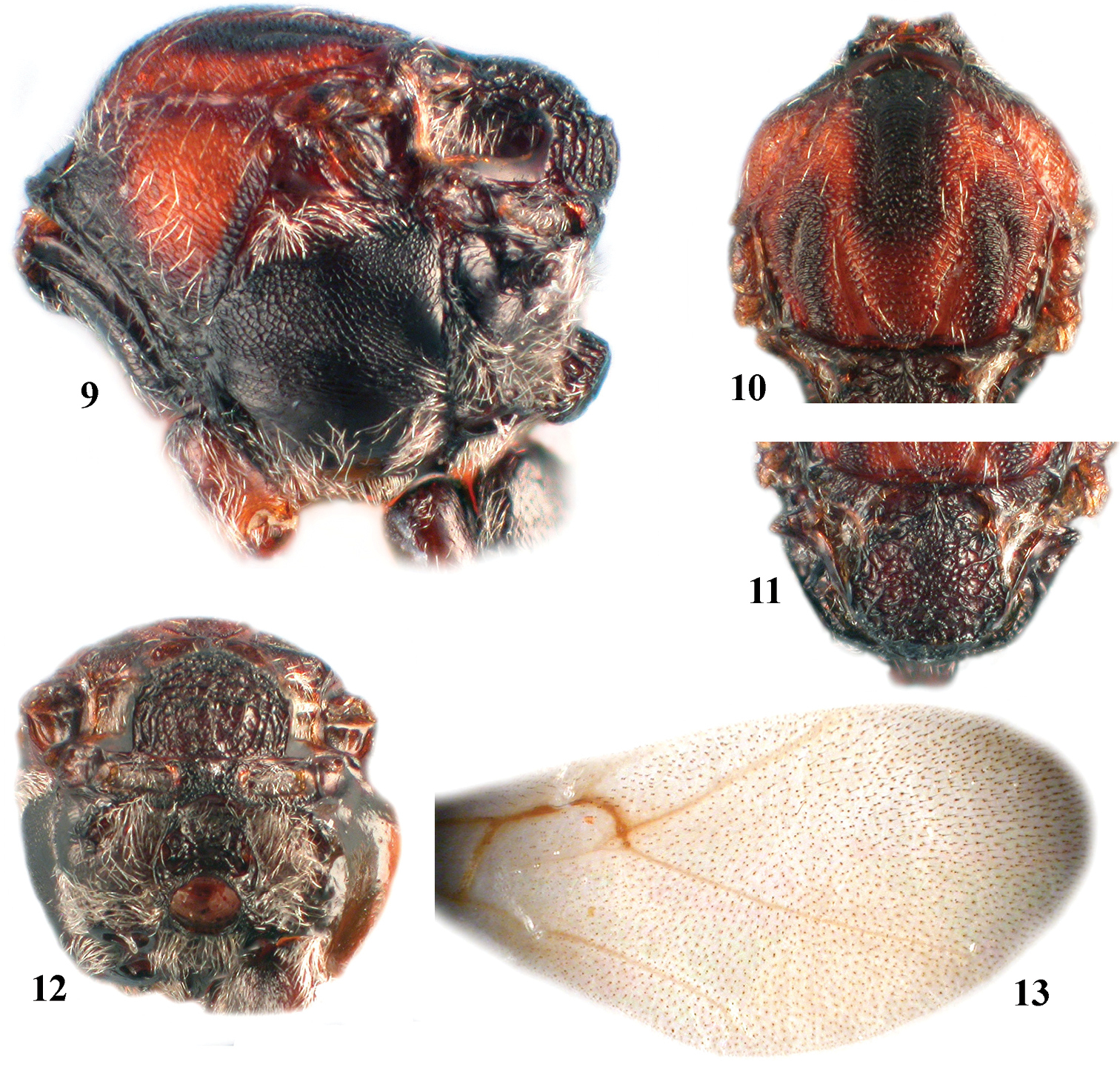

Zapatella grahami, female 9 mesosoma (lateral view) 10 mesoscutum (dorsal view) 11 mesoscutellum (dorsal view) 12 metascutellum and propodeum (posterodorsal view) 13 forewing.

Female (Figs 1–3, 6, 8, 9–16).

Length. 2.6–3.2 mm (n=15).

Coloration. Body, including antennae and legs predominantly dark to chestnut brown. Head, brown with more or less extensive black areas on lower face, basal part of genae, central part of frons and vertex; posteriorly head dark brown to black. Antenna uniformly dark brown, F1–F5 lighter; mesosoma laterally black, except brown dorsolateral area of pronotum; propleura black; mesoscutum brown, with black stripes along anterior parallel and parapsidal lines; mesoscutellum dark brown to black, with slightly lighter scutellar foveae. Propodeum uniformly black; axillula yellowish; legs uniformly brown, with darker hind legs; metasoma brown, anterodorsally darker.

Head (Figs 1–3). Uniformly and delicately reticulated, with few white setae, 1.8–2.0 times as broad as long from above, 1.3–1.5 times as broad as high in frontal view and slightly broader than mesosoma. Gena broadened behind eye, as broad as transverse diameter of eye; malar space 0.35–0.4 times as long as height of eye, with delicate striae radiating from clypeus and nearly reaching eye margin, malar sulcus absent. POL 1.4 times as long as OOL; OOL 2.5 times as long as length of lateral ocellus and 1.8 times as long as LOL. Transfacial distance nearly 1.2 times as broad as height of eye; diameter of antennal torulus around 3.8 times as great as distance between them, distance between torulus and inner margin of eye equal to or slightly longer than diameter of torulus; inner margins of eyes parallel; lower face delicately coriaceous, with dense white setae, the median elevated area smooth. Clypeus small, squared, smooth, impressed in basal part, ventrally straight; anterior tentorial pits, epistomal sulcus and clypeo-pleurostomal line indistinct. Frons, vertex, interocellar area and occiput delicately reticulate. Postocciput alutaceous and shiny, smooth and impressed around occipital foramen; posterior tentorial pits large; height of occipital foramen as long as height of postgenal bridge; hypostomal carina emarginate, not going around oral foramen, continuing into gular sulcus. Labial palpus 3-segmented, terminal peg distinct, all three segments densely setose; maxillary palpus 5-segmented, terminal peg distinct, three terminal segments densely setose.

Zapatella grahami 14 metasoma, female (lateral view) 15 metasoma, male (lateral view) 16 ventral spine of hypopygium (ventral view) 17–18 gall.

Antenna (Fig. 6). With 11 flagellomeres (14: 9×8: 15×8: 19: 15: 14: 13: 11: 10: 10: 9: 8: 16); longer than head+mesosoma (48:34); pedicel globose, as long as broad; F1 as long as scapus; F2 1.2–1.3 times as long as F1; F1=F3; F4–F5 subequal and shorter, F6–F10 shorter and progressively shortening in length; F11 twice as long as F10; placodeal sensilla distinct on F6–F11, indistinct but present on F4–F5, absent on F1–F3.

Mesosoma (Figs 9–12). 1.2–1.3 times as long as high in lateral view, with few white setae. Mesoscutum as long as broad, or only slightly longer than broad in dorsal view; with sparse scattered setae and transverse, delicate, interrupted striae which connect with longitudinally orientated weak striae, forming an irregular network of striae, and an irregularly reticulate surface sculpture. Notauli incomplete, extending at most to half length of mesoscutum; converging, deep and broad posteriorly. Anterior parallel lines extending to ½ length of mesoscutum; parapsidal lines distinct and broad, starting from posterior margin and extending to ½ length of mesoscutum; median mesoscutal line very short or absent. Mesoscutellum 0.5 times as long as mesoscutum, as long as broad, not overhanging metanotum, center of disk reticulate, sides and posterior 1/3 dull rugose; scutellar foveae present, ovate, not delimited posteriorly, bottom shiny, with some rugae; median carina broad. Mesopleuron uniformly delicately reticulate, smooth and shiny basally; mesopleural triangle conspicuously setose; dorsal axillar area coriaceous with numerous setae, lateral axillar area reticulo-carinate, without setae; axillula smooth, with white setae; subaxillular bar smooth, shiny, narrower than height of metanotal trough; postalar process long, strong, reticulate; metapleural sulcus reaching mesopleuron in upper 2/3 of its height. Metascutellum strongly reticulate, rectangular. Metanotal trough with short white setae; ventral impressed area at least twice as narrow as height of metascutellum, delicately reticulate. Propodeum setose lateraly, glabrous centrally; central propodeal area smooth, shiny, with many irregular wrinkles and rugae, lateral propodeal carinae weak, diverging anteriorly and converging in posterior 1/3. Nucha with irregular wrinkles and rugae.

Legs (Fig. 8). Tarsal claws simple, without basal lobe; hind coxae with dense white setae on the dorsoposterior surface.

Forewing (Fig. 13). Longer than body, hyaline, without cilia on margin; radial cell 3.3 times as long as broad; 2r distinct; R1 absent or hardly visible, Rs very inconspicuous, nearly straight; areolet absent or very indistinct. Rs+M indistinct, reaching basalis at half of its height.

Metasoma (Figs 14, 16). Shorter than head+mesosoma, slightly higher than long in lateral view; base of 2nd metasomal tergite with felt-like dense ring of white setae, interrupted dorsally and few setae scattered on lateral surface of tergite. Narrow posterior band on 2nd metasomal tergite and all subsequent tergites with very delicate dense micropunctures. Prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium needle-like, tapering to apex, 7.5–8.5 times as long as broad, with two parallel rows of short white scattered setae which do not extend beyond the apex of spine.

Male (Figs 4–5, 7, 15). Length 2.3–2.5 mm (n=4). Similar to female, except in the following characters: predominantly black with few brown areas; head 2.0 times as broad as long from above, 1.2 times as broad as high and broader than mesosoma in frontal view; malar space 0.3 times as long as height of eye; POL 2.0 times as broad as OOL; OOL 2.0 times as long as length of lateral ocellus and 1.3 times as long as LOL. Antennae with 13 flagellomeres (6: 4×4: 11×3.5: 10: 9: 9: 8: 8: 7: 7: 6: 6: 6: 6: 7); longer than body (101:93); pedicel as long as broad; F1 slightly longer than F2, distinctly curved, dorsally flattened and excavate; subsequent flagellomeres progressively shorter in length; F13 longer than F12; placodeal sensilla on all flagellomeres.

Gall (Figs 17–18). Acorn galls. Individual chambers located in the acorn cup, often between the cup and the seed. Usually there is one gall per acorn, but sometime two or three.

Biology. Only the sexual generation is known and it induces galls on Quercus costaricensis. Galls were collected in February and later in October in forests located above 3000 m altitude, adults emerged immediately after the galls were collected, in February and October. This very unusual emergence of adults in two periods may be due to the sporadic nature of the collecting and to the peculiar phenology of Quercus costaricensis. In the area where the galls were collected,

Currently known only from Costa Rica (Cerro de la Muerte).

In recognition of the continuing contribution of our friend, prof. Graham N. Stone (Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland) to research on oak gallwasps.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:7D783313-C344-41D4-BD4A-1D2E3E6EE4BB

HOLOTYPE female (deposited in IAvH): “COLOMBIA, Boyacá, Villa de Leyva, Vereda sabana, Sector Chaina, , 05°41'05.1"N, 73°29'17.3"W, 2468 m. En Agallas en ramas de Quercus humboldti, (13 May 2010) May-2010. leg. J. Pujade-Villar, C. Medina, M. Torres” (white label), Holotype of Zapatella nievesaldreyi ♀ Melika & Pujade-Villar n. sp. design. JP-V 2012” (red label). PARATYPES (93 females) with the same data as the holotype. 17 paratypes are deposited in UB, 8 in PDL and 70 in IAvH.

95 females with the same data as the holotype.

See Diagnosis of Zapatella grahami above. It also resembles the Nearctic Callirhytis medularis Weld (see Discussion).

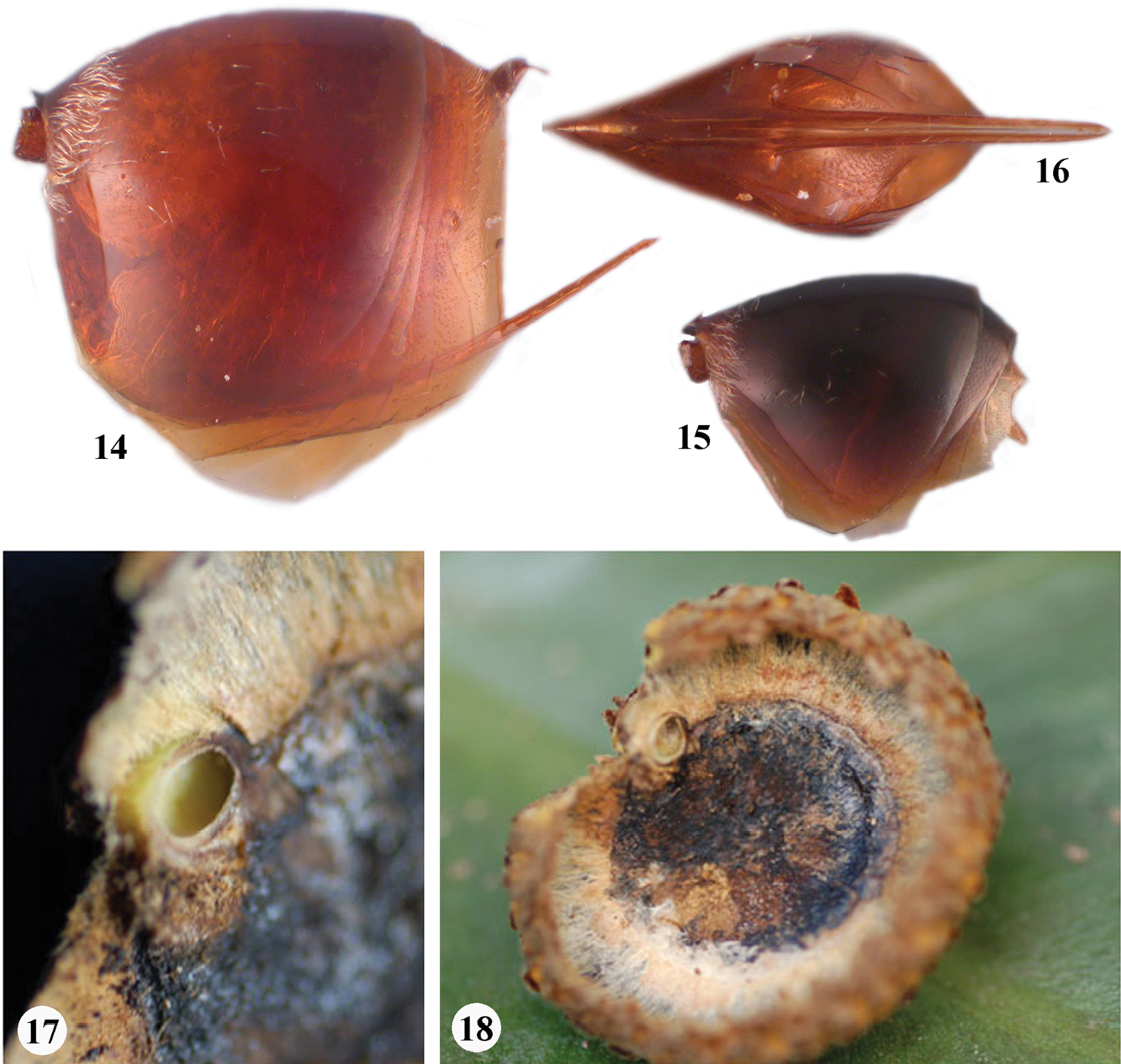

(Figs 19–30). Asexual form.

Length. Female 1.7–2.8 mm (n = 50).

Coloration. Body, antennae and legs uniformly reddish brown, only tips of mandibles, postocciput, propleura and tarsal claws always darker; in some specimens 3rd and subsequent tergites darker.

Head (Figs 19–21). Slightly broader than mesosoma, with few white sparse, short inconspicuous setae, more dense on lower face. Head very slightly transverse, only 1.2–1.3 times as broad as high in anterior view and massive from above, only 1.6–1.8 times as broad as long in dorsal view; gena broadened behind eye, broader than transverse diameter of eye, delicately uniformly reticulate; malar space without sulcus, 0.4–0.5 times as long as eye height, with striae radiating from clypeus and nearly reaching eye margin. Lower face delicately coriaceous, without elevated area medially. Clypeus slightly impressed, setose, alutaceous, rounded and slightly emarginate ventrally, medially not incised, anterior tentorial pits small, indistinct; epistomal sulcus and clypeo-pleurostomal line distinct. POL = OOL, OOL 2.5 times as long as length of lateral ocellus and 1.5 times as long as LOL, interocellar area microreticulate, not elevated; frons, vertex and occiput microreticulate; postocciput and postgenae alutaceous. Labial palpus 3-segmented, terminal peg distinct, all three segments densely setose; maxillary palpus 5-segmented, terminal peg distinct, three terminal segments densely setose.

Zapatella nievesaldreyi, female 19 head (anterior view) 20 head (dorsal view) 21 head (posterior view) 22 mesosoma (dorsal view) 23 mesosoma (lateral view) 24 tarsal claw.

Antenna (Fig. 25). 11 flagellomeres, slightly longer than combined length of head and mesosoma; pedicel slightly longer than broad; F1 length nearly equal to length of F2 and slightly longer than F3; F6–F10 shorter and broader than preceding segments; F11 2.0 times as long as F10; placodeal sensilla on F5–F11, hardly traceable or invisible on F1–F4.

Zapatella nievesaldreyi, female: 25 antenna 26 forewing 27 metascutellum and propodeum (posterodorsal view) 28 metasoma (lateral view) 29 metasoma with ventral spine of hypopygium (lateral view) 30 female habitus (lateral view) 31 twigs with galls.

Mesosoma (Figs 22–23, 27). 1.4 times as long as high, mesoscutum dorsally concave in later view. Pronotum setose, with uniformly delicately reticulate sides, without carinae posterolaterally. Mesoscutum slightly broader than long in dorsal view, with sparse scattered setae; with transverse, delicate interrupted striae which are connected with longitudinally orientated weak striae forming an irregular network of striae, together forming an irregular reticulate surface sculpture. Notauli extending nearly to half length of mesoscutum, deep and broad posteriorly, narrowing toward anterior end, with smooth bottom; median mesoscutal line absent or present in a form of short triangle; parapsidal lines distinct, extending to half length of mesoscutum; anterior parallel lines distinct, extending to 1/3 length of mesoscutum. Mesopleuron uniformly reticulate. Mesoscutellum as broad as long in dorsal view, centrally delicately coriaceous, dull rugose along sides and in posterior 1/3; scutellar foveae transversely ovate, with smooth and shiny bottom, distinctly separated medially by elevated coriaceous area. Metascutellum rugose, higher than height of smooth, shiny ventral impressed area of metanotum; metanotal trough smooth, shiny, with numerous white setae. Propodeum coriaceous, with dense white setae laterally; with smooth, shiny central propodeal area, delimited by distinct parallel lateral carinae, which slightly converge in posterior 1/3; anterior half of central propodeal area with dense white setae, posterior half without setae. Nucha with longitudinal rugae.

Forewing (Fig. 26). Nearly as long as body, pubescent, without cilia on margins; radial cell open, around 3.5 times as long as broad; veins very light, hardly traceable; areolet indistinct, usually invisible; vein Rs+M points slightly below midway along basalis; R1 and Rs never reach wing margin, very inconspicuous, often invisible or absent.

Legs (Fig. 24). Tarsal claws simple, without basal lobe, but with broad base; hind coxae with dense white setae dorsoposteriorly.

Metasoma (Figs 28–29). As long as head and mesosoma together, slightly longer than high; all metasomal tergites smooth and shiny; base of 2nd metasomal tergite with felt-like dense ring of white setae, interrupted dorsally, and a few scattered setae on lateral surface of tergite. Narrow posterior band on 2nd metasomal tergite and all subsequent tergites with very delicate, dense micropunctures. Prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium needle-like, tapering to apex, 6.0–7.0 times as long as broad, with two parallel rows of short, white, scattered setae.

Gall (Fig. 31). Inconspicuous galls in twigs, without visible enlargement (swelling) of the infested twig (branch). The larval cells, 2×1 mm, are nested in the wood parallel one to another.

Only females are known to induce galls hidden in twigs on Quercus humboldtii. Twigs with galls were collected in May and adult wasps immediately emerged in the same month.

Currently known only from Colombia, Boyaca, from deciduous mixed broad-leaved forests located about 2000 m altitude.

In recognition of the continuing contribution of Dr. José Luis Nieves-Aldrey (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales-CSIC, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Madrid, Spain) to research on oak gallwasps.

Five Nearctic Callirhytis species possess the same character set as the above two species and thus they are transferred to Zapatella.

http://species-id.net/wiki/Zapatella_cryptica

Figures 32–38, 59, 61One paratype female: ‘Dolhan, Ala, May; Quercus digitata; 1188; Paratype No. 24725 USNM’.

Only the asexual generation is known. It induces bud galls on Quercus myrtifolia Willd. and Quercus falcata Michx. in the USA (Florida and Alabama) (

Type galls were collected in October and adults emerged the next year in May (Weld 1922). The affected terminal bud cluster becomes enlarged, one or two green leaves sometimes grow out beyond the bud scales, and later the bud turns brown; the gall is completely hidden within the bud and is conical, with a thin-walled cell and a tuft of hairs near the apex (

The female is entirely uniformly reddish brown and the notauli are incomplete, reaching to 3/4 of the mesoscutum length, but darker lines that look like notauli reach the anterior margin of the mesoscutum; the median mesoscutal line is impressed and reaches the pronotum; the prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium is 6.3 times as long as broad. See also the Zapatella species key.

Zapatella cryptica, female 32 head (anterior view) 33 head (dorsal view) 34 head (posterior view) 35 antenna 36 hind coxa 37 mesosoma (lateral view) 38 mesosoma (dorsal view).

http://species-id.net/wiki/Zapatella_herberti

Figures 39–45Two paratype females: ‘Placerville Cal., May 21’18; 1615; Paratype No. 27223 USNM; Eumayria herberti’ and ‘Placerville Cal.; cut out May 13; 1615; Paratype No. 27223 USNM; Eumayria herberti’.

Only the asexual generation is known. It induces stem swelling galls on Quercus agrifolia Née, Quercus kellogii Newb., Quercus wislizeni A. DC in California (USA) (

The female is unifromly reddish brown, including the metasoma. The notauli are complete, always reaching pronotum, deeply impressed; the median mesoscutal line is short, extending to 1/4 of the mesoscutum length, beyond which it is indicated by a dark line only. The metasoma has a ring of very dense white setae at the base of the 2nd metasomal tergite, interrupted dorsally; the metasoma is slightly higher than long in lateral view. The 2nd metasomal tergite is smooth, shiny, without pnctures, while the next tergites have micropunctures. The ventral spine of the hypopygium is hidden under the tergites, its prominent part 6.1 times as long as broad ventrally. See also the key to Zapatella species.

Zapatella herberti, female 39, head (anterior view) 40 head (dorsal view) 41 head (posterior view) 42 antenna 43 mesosoma (lateral view) 44 mesosoma (dorsal view) 45 metascutellum and propodeum (posterodorsal view).

http://species-id.net/wiki/Zapatella_quercusmedullae

Figures 46–51One paratype female: ‘Jacksonville; collector Ashmead; Paratype No. 1497; Andricus medullae Ashm. (handwritten label)’.

Only the asexual generation is known. It induces stem swelling galls, in spring, on Quercus incana Bartram (= Quercus cinerea Raf.), Quercus marilandica (L.) Münchn. and Quercus myrtifolia in the USA (Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Missisipi, Texas) (

The female, like the previous species, has the notauli incomplete, extending to half of the mesoscutum length, with darker lines that resemble notauli reaching the anterior margin of the mesoscutum. The median mesoscutal line is absent. The prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium is 6.2 times as long as broad ventrally. See also the key to Zapatella species.

Zapatella quercusmedullae, female 46 head (anterior view) 47 head (dorsal view) 48 head (posterior view) 49 antenna 50 mesosoma (lateral view) 51 mesosoma (dorsal view).

http://species-id.net/wiki/Zapatella_quercusphellos

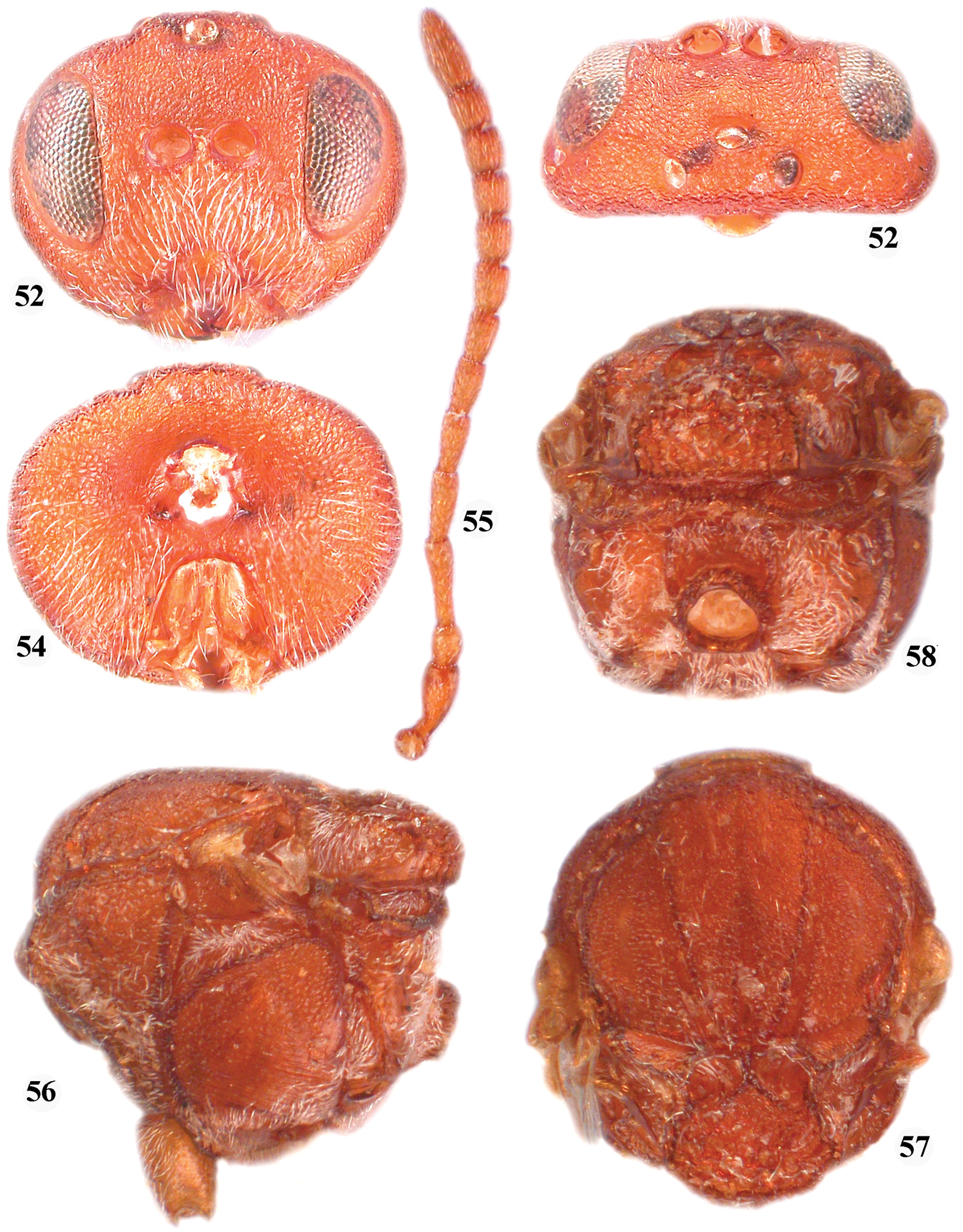

Figures 52–58, 60, 62For Cynips quercusphellos: One paratype female:Osten-Sacken coll.; Type (red); Paratype 24684, USNM (red); Cynips quercus-phellos OS from M.C.Z 1921 exchange. One female: Mnt Vernon, Va., 16, 1916, WLMaCtee collector. Callirhytis phellos (OS) det. Weld, 1942 (Weld’s handwriting labels); other female: Alachua Co., Fl., Gainesville, III.27.1924. T.H.Hubbell. Callirhytis quercusphellos (OS) det. Weld, 1925 (Weld’s handwriting label). The two specimens were compared by GM to the Osten Sacken’s cotype, deposited at the USNM (Washington, DC) and obtained by L.H. Weld from the Museum of Comparative Zoology by exchange (

Callirhytis (Cynips) quercussimilis (sexual form) was known, inducing stem swelling galls on Quercus incana, Quercus falcata, Quercus ilicifolia Wangenh., Quercus imbricaria Michx., and Quercus myrtifolia along the Atlantic coast, from Florida to New York state (

The author of Callirhytis quercusphellos (

Zapatella quercusphellos was collected also at Rosslyn, Virginia from Quercus imbricaria in June and Quercus phellos in May, adults emerged in late June. In both cases the greenish fresh galls were similar terminal enlargements on new growths, inconspicuous, only 5 mm long; after maturation galls were 8–10 mm in diameter (

A detail examination of specimens of Callirhytis quercusphellos and Callirhytis quercussimilis, mentioned above, showed no appreciable morphological differences and thus, Callirhytis quercussimilis is a syn. n. of Callirhytis quercusphellos and here in the species transferred to the Zapatella genus, Zapatella quercusphellos, comb. n. Females are uniformly dark reddish brown; the notauli are incomplete, extending to half the mesoscutum length, with darker lines reaching the anterior margin of the mesoscutum; the median mesoscutal line extending to 1/2 of the mesoscutum length, further indicated by a dark line only; the prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium is 6.2 times as long as broad ventrally. The male is much darker than the female, with a dark brown head and mesosoma, while the metasoma is slightly lighter (otherwise quite similar to Zapatella grahami). See also the key to Zapatella species.

Only the sexual generation is known. It induces stem swelling galls on Quercus incana, Quercus falcata, Quercus ilicifolia Wangenh., Quercus imbricaria, Quercus myrtifolia and Quercus phellos along the Atlantic coast, from Florida to New York state (

Zapatella quercusphellos, female 52 head (anterior view) 53 head (dorsal view) 54 head (posterior view) 55 antenna 56 mesosoma (lateral view) 57 mesosoma (dorsal view) 58 metascutellum and propodeum (posterodorsal view).

59 Zapatella cryptica, metasoma, female (lateral view) 60 Zapatella quercussimilis, metasoma, female (lateral view) 61 Zapatella cryptica, ventral spine of hypopygium 62 Zapatella quercussimilis, ventral spine of hypopygium.

http://species-id.net/wiki/Zapatella_oblata

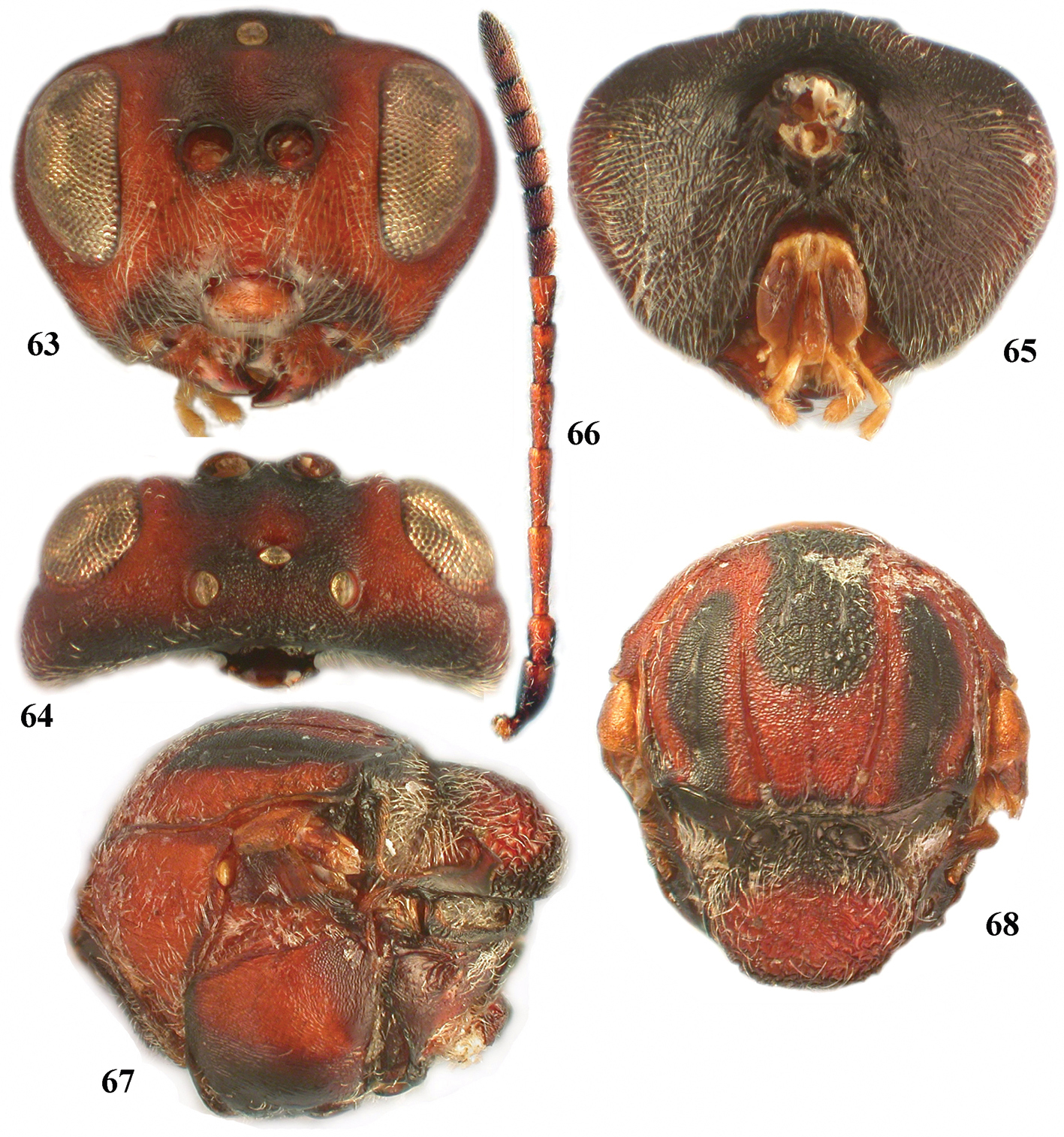

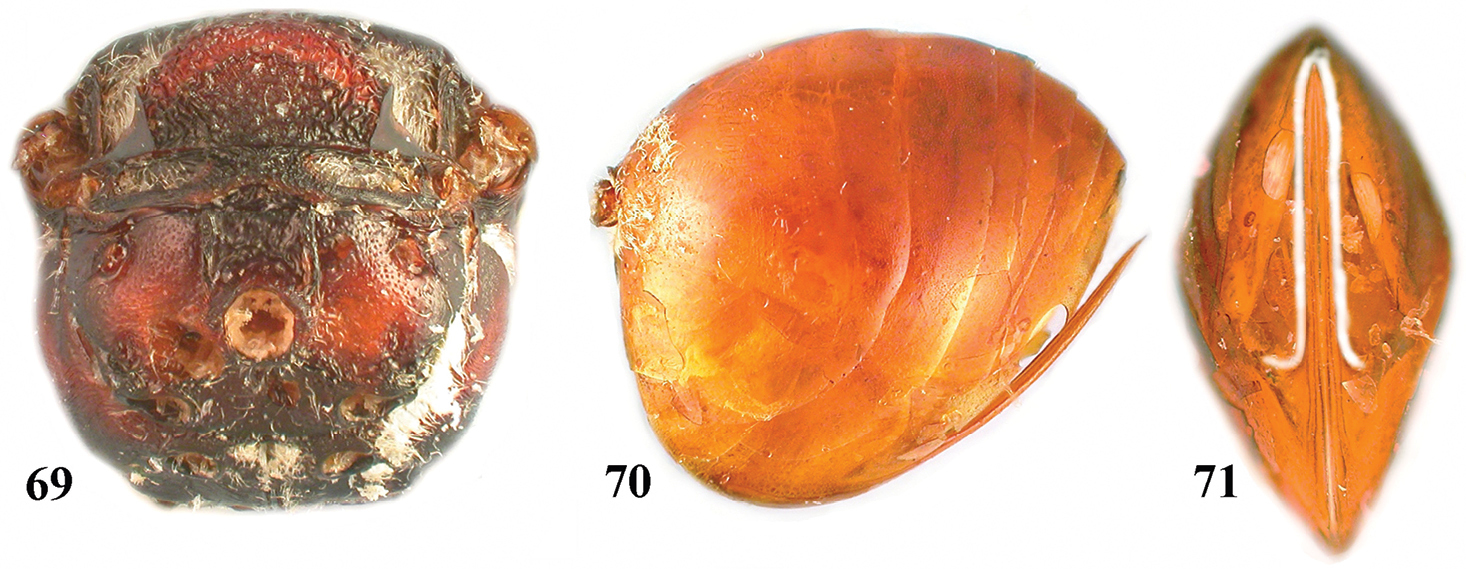

Figures 63– 71Paratype female: Vienna, Va., March 21’46. Q. coccinea, 558, Paratype 60128, Callirhytis oblata Weld.

Only the asexual generation is known. It induces bud galls on Quercus coccinea Muench. and Quercus falcata in Virginia, USA (

Zapatella oblata, female 63 head (anterior view) 64 head (dorsal view) 65 head (posterior view) 66 antenna 67 mesosoma (lateral view) 68 mesosoma, (dorsal view).

Zapatella oblata, female 69 metascutellum and propodeum (posterodorsal view) 70 metasoma (lateral view) 71 ventral spine of hypopygium (ventral view).

| 1 | Female, antenna with 11 flagellomeres | 2 |

| – | Male, antenna with 13 flagellomeres | 8 |

| 2 | Median mesoscutal line extending to 1/3–2/3 of mesoscutum length, deeply impressed (Figs 38, 57) | 3 |

| – | Median mesoscutal line very short or absent (Figs 10, 22, 51) | 5 |

| 3 | Median mesoscutal line impressed to 1/2 of mesoscutum length, indicated beyond this by dark line; prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium 6.2 times as long as broad in ventral view (Figs 60, 62). Stem swelling galls | Zapatella quercusphellos |

| – | Median mesoscutal line extending to 2/3 of mesoscutum length; prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium at least 8.0–8.5 times as long as broad in ventral view (Figs 59, 61, 71). Bud galls | 4 |

| 4 | Head and mesosoma uniformly reddish brown (Figs 32–38); scutellar foveae quadrangular, as long as broad (Fig. 38) | Zapatella cryptica |

| – | Head and mesosoma with large dark brown to black patches (Figs 63–68); scutellar foveae transverse, broader than high (Fig. 68) | Zapatella oblata |

| 5 | Body darker, head and mesosoma always with large dark brown to black spots (Figs 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, 12); POL 1.4 times as broad as OOL (Fig. 2); bottom of scutellar foveae with rugae (Fig. 11); prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium 7.5-8.5 times as long as broad (Figs 14, 16). Acorn galls (Figs 17–18) | Zapatella grahami |

| – | Body entirely and uniformly light reddish brown, without or with very few darker spots; POL equal to OOL (Fig. 20, 40); bottom of scutellar foveae smooth, without rugae (Fig. 22, 44); prominent part of ventral spine of hypopygium 6.0–7.0 times as long as broad (Figs 29–30). Galls in twigs | 6 |

| 6 | Notauli complete, always reaching pronotum, deeply impressed (Fig. 44). Stem swelling galls with larval chambers nested in the peripheral layer of wood | Zapatella herberti |

| – | Notauli incomplete, extending to 1/2 of mesoscutum length, never reaching pronotum (Figs 22, 51). Galls in twigs with larval chambers nested in the wood | 7 |

| 7 | Head in anterior view ovate (Fig 46), less robust and transverse from above (Fig. 47); scutellar foveae separated by very thin, line-like median carina (Fig. 51); lateral propodeal carinae subparallel, extending the entire length (as in Fig. 58). Stem swelling galls | Zapatella quercusmedullae |

| – | Head in anterior view rounded (Fig 19), robust and less transverse (Fig 20); scutellar foveae separated by broad bar (Fig 51); lateral propodeal carinae slightly bent outwards in posterior 1/3 (Fig. 27). Inconspicuous galls in twigs (Fig. 31) | Zapatella nievesaldreyi |

| 8 | Gena width nearly equal to transverse diameter of eye; scutellar foveae not separated by median carina, not delimited posteriorly, with reticulate bottom. Acorn galls (Figs 17–18) | Zapatella grahami |

| – | Gena width no more than 1/3 of transverse diameter of eye; scutellar foveae separated by distinct median carina, well-delimited all around, with smooth shiny bottom. Stem swelling galls | Zapatella quercusphellos |

Although the newly described genus Zapatella, somewhat resembles Bassettia, Loxaulus, and Plagiotrochus (see Diagnosis to Zapatella and Table 1), it most closely resembles Callirhytis ‘sensu lato’ (

Generic characteristics of Zapatella and allied genera (exclusive generic characters of Zapatella are in bold)

| Characters | Loxaulus | Bassettia | Plagiotrochus | Callirhytis | Zapatella |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malar sulcus | present | absent | absent | present | absent |

| Mesoscutum sculpture | reticulate | reticulate | transversely coriaceous or rugose | transversely strongly carinated | reticulate |

| Pronotum sculpture | reticulate | reticulate | fine striae | strong striae | reticulate |

| Metascutellum sculpture | rugoso-reticulate | reticulate | rugoso-reticulate | rugose | rugoso-reticulate |

| Metanotal trough | glabrous | glabrous | glabrous | glabrous | pubescent |

| Ventral spine | short (<2.5) | short (<2.0) | short (<3.0) | short (<4.0) | long (>6.0) |

| Head fom above | massive | massive | oblong/lunate | oblong/lunate | massive |

| Sculpture of mesopleuron | uniformly reticulate | uniformly reticulate | with transverse sculptured band only | glabrous or coriaceous | with transverse sculptured band only |

| Propodeal carinae | subparallel | subparallel | strongly bent outwards | subparallel | subparallel |

| Hind coxae dorsoposterior surface | glabrous | glabrous | glabrous | glabrous | pubescent |

| Forewing margin | variable | no cilia | with cilia | no cilia | no cilia |

| F1 in male incised | yes | no | yes | yes | yes |

| R1 and Rs veins | conspicuous | conspicuous | conspicuous | conspicuous | inconspicuous |

| Scutellar foveae | anterior impression, not separated | present, posteriorly undefined | present, posteriorly undefined | present, posteriorly undefined | present, well-delimited posteriorly |

| 2nd metasomal tergite, lateral setae | glabrous, few setae | glabrous, few setae | glabrous, few setae | glabrous, few setae | with dense ring of setae |

| 3rd metasomal tergite | smooth | smooth | smooth | smooth | punctate |

The newly established Zapatella, with the two described neotropic species and five transferred Callirhytis species, is the first contribution to this ‘reorganization’ of the Nearctic Callirhytis ‘sensu lato’. Some Callirhytis species (Callirhytis balanaspis Weld, Callirhytis corrugis (Bassett), Callirhytis glomerosa Weld, and Callirhytis medularis Weld) partially resemble Zapatella in their host plant associations, morphology of adults and/or galls they induce, and thus need some explanation.

Callirhytis balanaspis Weld (only the asexual generation is known) induces acorn galls on red oaks, also has a very pale venation, R1 invisible, the malar sulcus absent, the mesoscutum with delicate, net-like reticulate transverse sculpture, as in Zapatella. However, the ring of very dense white setae at the base of the 2nd metasomal tergite is absent and the prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium is only 3.0–3.5 times as long as broad. This species is definitely not a Callirhytis ‘sensu stricto’, it closely resembles Zapatella, and form a discrete unit within Callirhytis ‘sensu lato’.

In Callirhytis corrugis (Bassett), which induces acorn galls on red oaks (

In Callirhytis glomerosa Weld, which induces bud galls on red oaks, the malar sulcus is absent, the ring of very dense white setae at the base of the 2nd metasomal tergite is present, the hind coxae have dense white setae on the dorsoposterior surface as in Zapatella; the mesoscutum is very finely transversely rugose and the prominent part of the ventral spine of the hypopygium is much shorter, as in Callirhytis. However, it differs form both genera in the trapezoid head in anterior view (much shorter from above) and the female antenna with 12 flagellomeres. This species is definitely not a Callirhytis ‘sensu stricto’, closely resembles Zapatella, and forms a discrete unit within Callirhytis ‘sensu lato’.

Callirhytis medularis Weld induces stem swelling galls on red oaks and is only known from the sexual generation. However, in Callirhytis medularis, the female antenna has 12 flagellomeres, the head is more massive from above, much broader than the mesosoma; the mesoscutum is dull rugose, with strong transverse ridges, the mesoscutellum broader than long, the metanotal troughs and hind coxae without dense white setae, the 2nd metasomal tergite without a ring of dense white setae at the base; the ventral spine of the hypopygium is much shorter. This species is definitely not a Callirhytis ‘sensu stricto’, closely resembles Zapatella, and forms a discrete unit within Callirhytis ‘sensu lato’.

Preliminary morphological analysis (GM and JPV, umpublished data) also showed that some Nearctic Callirhytis species that induce stem swelling galls on different sections of oaks, form distinct morphological and phylogenetic units. Thus, some of these discrete morphological groups form distinct genera, which might be monophyletic groups.

We thank Palmira Ros-Farré (Barcelona University, Spain) for taking the SEM pictures included in this study; Matthew Buffington (USNM, Washington, DC, USA) for providing the possibility of working with material in the USNM.