(C) 2011 Jonathan R. Mawdsley. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

A key is presented for the identification of the four species of Anthia Weber (Coleoptera: Carabidae) recorded from the Republic of South Africa: Anthia cinctipennis Lequien, Anthia circumscripta Klug, Anthia maxillosa (Fabricius), and Anthia thoracica (Thunberg). For each of these species, illustrations are provided of adult beetles of both sexes as well as illustrations of male reproductive structures, morphological redescriptions, discussions of morphological variation, annual activity histograms, and maps of occurrence localities in the Republic of South Africa. Maps of occurrence localities for these species are compared against ecoregional and vegetation maps of southern Africa; each species of Anthia shows a different pattern of occupancy across the suite of ecoregions and vegetation types in the Republic of South Africa. Information about predatory and foraging behaviors, Müllerian mimicry, and small-scale vegetation community associations is presented for Anthia thoracica based on field and laboratory studies in Kruger National Park, South Africa.

Anthia, Carabidae, taxonomy, identification, savanna, South Africa, Apristis promontorii Péringuey

Beetles in the genus Anthia Weber are some of the largest and most conspicuous representatives of the family Carabidae in sub-Saharan Africa (

Adult female of Anthia thoracica (Thunberg), photographed in the N’waswitshaka Research Camp, Skukuza, Kruger National Park, Republic of South Africa.

Adult male of Termophilum homoplatum (Lequien), photographed in the N’waswitshaka Research Camp, Skukuza, Kruger National Park, Republic of South Africa.

Unfortunately, studies of the ecology, evolution, and behavior of these beetles have long been hampered by the lack of reliable, illustrated identification materials for species of Anthia and related genera. The two older revisions by

The present treatment was written to provide identification materials for species of Anthia (sensu

Unlike many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the Republic of South Africa has been well sampled for Anthia and related genera and there is a wealth of museum material available for study. Even with this wealth of material, there has been considerable confusion in the literature regarding the identification and appropriate names to assign to these species. At the level of generic names, many authors follow

There has also been considerable confusion regarding the number of species of Anthia in southern Africa.

We examined specimens of species of Anthia, Termophilum, and allied genera in the collections of the following museums: Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois (FMNH); Kruger National Park Museum (Scientific Services), Skukuza, South Africa (KNPC); South African National Collection of Insects, Pretoria, South Africa (SANC); National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (NMNH); Transvaal Museum, Pretoria, South Africa (TMSA).

Field observations on adults of Anthia thoracica and other Anthiini were conducted during month-long visits by the senior author to the Kruger National Park in 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010. Systematic field surveys for Anthiini and other diurnally active Carabidae were conducted in areas where adults of Anthiini had been collected historically in the park, or where adult beetles had been observed recently by park staff. Our surveys focused primarily on the Skukuza Ranger District in the central portion of the park, with field trips north to Satara, Letaba, Olifants, and Shingwedzi and south to Pretoriuskop. In surveying these areas we employed a variety of techniques, including driving surveys, walking surveys, and pitfall trapping (

The driving technique proved to be a particularly productive method for collecting Anthiini, as well as other large Carabidae such as species of Tefflus Leach (

For studies of beetle biology in captivity, individual adult beetles were captured by hand and placed singly into large 4-liter plastic holding containers containing a shallow layer of sand and gravel in the bottom. Each container was provided with a small ball of cotton soaked in water, to provide a water source for the adult beetles. To examine prey preferences, we provided each captive beetle with a variety of potential food items, primarily insects and other arthropods which were collected at lights at night in the Skukuza research camp. We recorded acceptance/rejection of each potential food item and the associated order and family of each prey item offered to the beetles.

Voucher specimens of beetles collected in Kruger National Park are deposited in the KNPC, NMNH, and TMSA collections.

Attributes of the abdominal ventral sterna are referred to using the numbering system generally accepted in Carabid studies, i.e., the sternum divided medially by the hind coxae is sternum II (the first being hidden) and the last visible is sternum VII (

http://species-id.net/wiki/Anthia

Body large and massive, adults of South African species always 40 mm or greater in length; body black or dark brown, usually with yellow or white setae and pubescence. Prothorax cordiform, distinctly expanded laterally and usually with large lateral flanges. Mandibles and prothorax sexually dimorphic: mandibles elongate in males, shorter in females; base of pronotum with two posterior flanges or flattened extensions in males, tumescent without extensions in females. Elytra smooth with rows of minute punctures or feebly striatiopunctate, never markedly striatiopunctate in South African species (although other species in the genus do have striatiopunctate elytra).

Specimens of southern African species of Anthia may be readily distinguished from those of allied genera by the presence of broad lateral flanges on the pronotum and the sexual dimorphism in the structure of the mandibles and pronotal base. Most other South African Anthiini also have the elytra markedly striatiopunctate, at least in part. The only sympatric genus with which species of Anthia might be confused is Termophilum Basilewsky, that contains several large species that are similar in overall appearance and markings with those of the genus Anthia. However, species of Termophilum have a much simpler pronotal structure that lacks the large lateral flanges and secondary sexual characteristics present in Anthia species. Species of Termophilum also lack the sexual dimorphism in the mandibles that is seen in species of Anthia.

| 1 | Elytra with a distinct band of white setae along lateral margins | 2 |

| – | Elytra lacking distinct band of white setae along lateral margins | Anthia maxillosa (Fabricius) |

| 2 | Pronotum with lateral patches of white, yellow, or brown setae; aedeagus stout, thick | 3 |

| – | Pronotum lacking lateral patches of white, yellow, or brown setae; aedeagus narrow, elongate | Anthia cinctipennis Lequien |

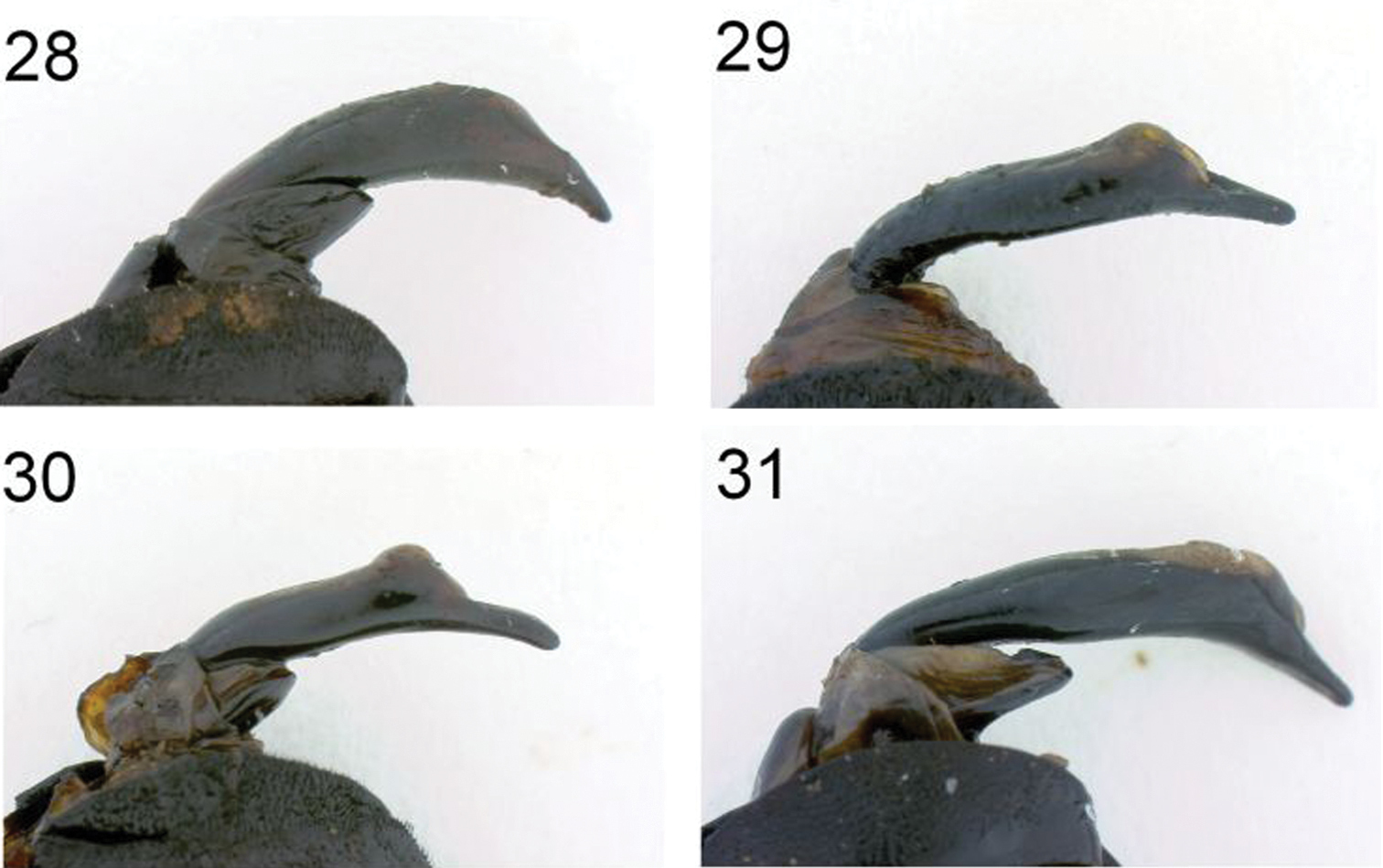

| 3 | Lateral flanges of pronotum with large patches of dense yellow or brown reclinate seta forming two large round or ovate “spots;” aedeagus stout and thick along entire length (Figure 28) | Anthia thoracica (Thunberg) |

| – | Lateral flanges of pronotum with more-or-less distinct patches of suberect white setae; aedeagus thinner towards base (Figure 31) | Anthia circumscripta Klug |

http://species-id.net/wiki/Anthia_thoracica

Figures 1, 3–11, 28, 32, 36“Capite bonae spei” (= Cape of Good Hope).

Carabus thoracicus and Carabus fimbriatus, Uppsala University, Museum of Evolution, Zoology Section; Anthia portentosa, formerly in the Museum für Naturkunde Stettin, and apparently lost in World War II; Anthia thoracica var. stigmodera, South African Museum, Iziko Museums of Cape Town.

Easily separated from sympatric species of Anthia by the large round or ovate patches of yellow or brown setae on the lateral flanges of the pronotum. Anthia thoracica is the most widespread species of Anthia in South Africa and although adults are usually encountered singly, the species can be locally abundant.

Body size massive, length of male (exclusive of mandibles) 46.8-52.8 mm, length of female 40.5-50.3 mm. Integument black.

Head elongate, prognathous. Mandibles elongate and sickle-shaped in male, short and stout in female. Male mandibles asymmetrical, with left mandible more markedly recurved than right. Length of right mandible in male 9.9-14.7 mm. Palpi elongate, slender, terminal segment securiform. Antennae elongate, antennomeres 1-3 and the base of 4 with small white reclinate setae dorsally; antennomeres 5-11 with brown pubescence. Eyes small, moderately convex. Frons markedly impressed, with fine scattered round punctures and an irregular median tubercle. Vertex smooth, with small scattered round punctures.

Pronotum cordiform, with broad lateral flanges, distinctly broader than head in both sexes. Two well-defined round or oval patches of short reclinate yellow setae present, one patch on each of the lateral flanges of the pronotum. Pronotum in male with large longitudinal median impression and with two large basal flanges projecting over base of elytra, lateral margins of flanges markedly elevated, apical margins oblique. Pronotum in female markedly impressed medially, lacking basal flanges but with two large, broad tubercles at base. Pronotal surface rugosely punctate medially, smooth with scattered small round punctures otherwise. Scutellum triangular, small and nearly obsolete. Elytra ovate, moderately convex. Elytral surface smooth, with 8 linear striate interneurs (feebly impressed or nearly obsolete in South African specimens) and scattered small round punctures. Elytral disc with short, scattered brown setae. Lateral margins of elytra with a well-defined band of short white reclinate setae. Femora large, massive, with large round punctures. Tibiae elongate, slender, with lateral carinae, protibiae with antennal cleaner notch and a single stout subtending seta, meso-and meta-tibiae thickened at end, with dense reclinate brown setae towards apices and an apical setal fringe, tibial spurs 1-2-2. Tarsi stout, densely setose, protarsi in male broadly expanded, with comb-like setae ventrally.

Abdomen convex, shining, with numerous small round punctures and transverse wrinkles, especially towards lateral margin of ventrites. Apex of sternum VII feebly emarginate in male and broadly rounded in female. Male aedeagus stout, thick (Figure 28).

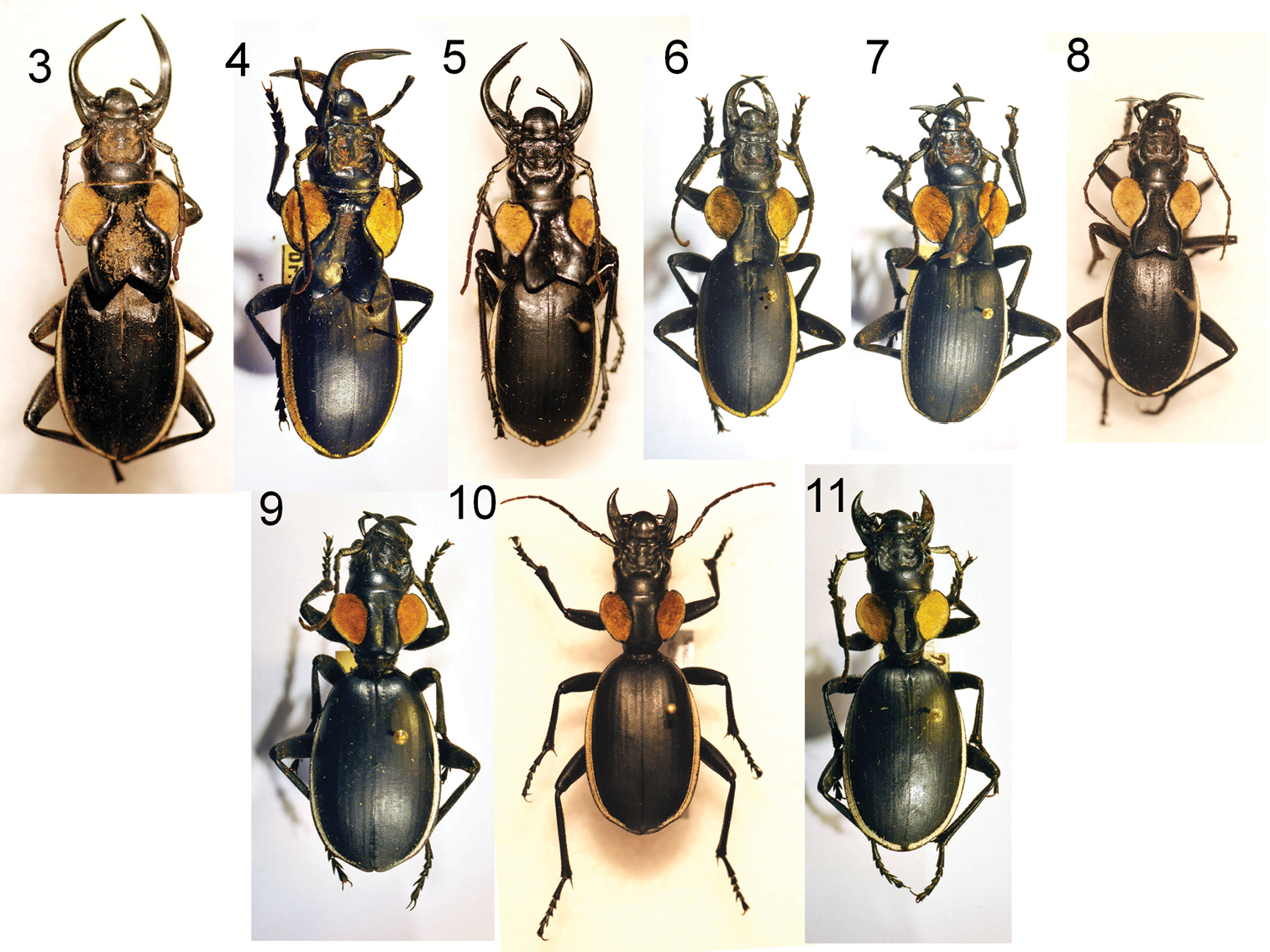

Six adult males (3–8) and three adult females (9–11) of Anthia thoracica (Thunberg), showing variation in male mandible length, in the size of the pronotal flanges in males, and in body size in both sexes. 3 male, Willowmore, Eastern Cape Province, RSA, NMNH 4 male, Lichtenburg, North West Province, RSA, TMSA 5 male, Queenstown, Eastern Cape Province, RSA, NMNH 6 male, Thabina, Gauteng Province, RSA, TMSA 7 male, Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga Province, RSA, TMSA 8 male, Lichtenburg, North West Province, RSA, NMNH 9 female, Farm Alfa, Mpumalanga Province, RSA, TMSA 10 female, vic. Hazyview, Mpumalanga Province, RSA, NMNH 11 female, Bothaville, Free State Province, RSA, TMSA.

Males exhibit considerable variation in the size and length of mandibles and in the size of the basal flange on the pronotum (Figures 3-8). Females also exhibit some variability in overall body size (Figures 9-11).

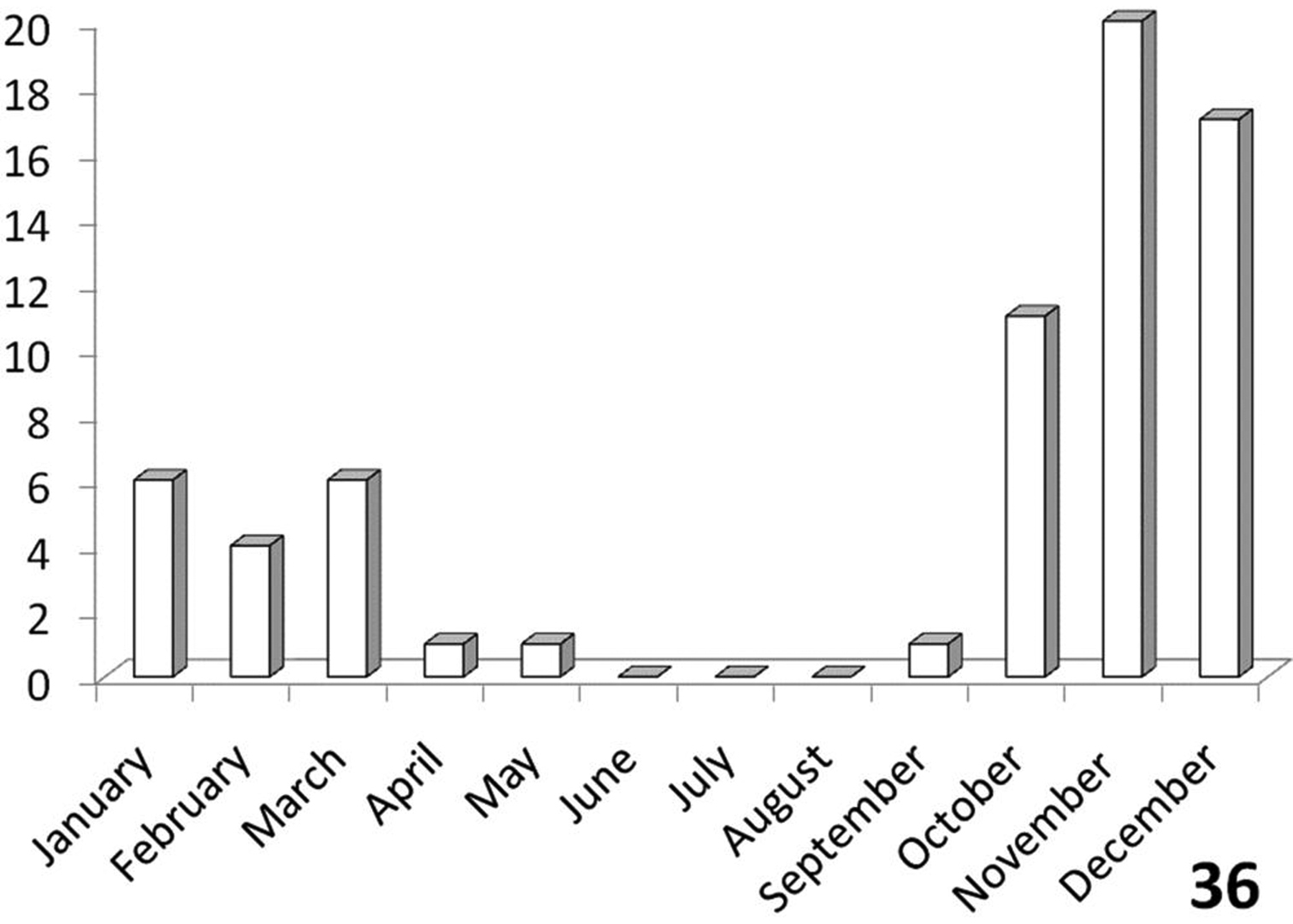

Unimodal, with greatest activity from October to March (Figure 36).

164 pinned adult specimens from the following localities: Republic of South Africa: Eastern Cape Province: Algoa Bay, Despatch, Grahamstown, Port Elizabeth, Port St. Johns, Queenstown, Willowmore. Free State Province: Bothaville, Hendrik Verwoerd Dam, Krugersdrift Dam, Vanwyksfontein Farm, Winburg. Gauteng Province: Boksburg, Cullinan, Florida, Heidelberg, Johannesburg, Pienaars River, Pretoria, Thabina, Valhalla, Zoutpan Pta. KwaZulu-Natal Province: Hluhluwe, Ndumu, Pongola River, “E. Zululand, ” “Zululand.” Limpopo Province: Groblersdal, Leydsdorp, Messina, Mogaladi, Mokeetse, Pietersberg, 20-26 miles NE of Pietersberg, Pumbe Sands, Shilouvane, Shingwedzi, Warm Baths, Zebediela, Zoutpansberg. Mpumalanga Province: Barberton, Bushbuckridge, Farm Alfa, Elands River/Middelburg, Groot draai on the Olifants River, Hazyview, vic. Hazyview, Malelane, Nelspruit, Numbi Gate, N’waswitshaka Research Camp, Skukuza, Stolsnek, Waterval pass, Waterval river pass. Northern Cape Province: De Aar, Kimberley. North West Province: Hartebeespoort Dam, Lichtenburg, Mafeking, Rustenburg, 14 miles E Ventersdorp. Western Cape Province: Cape of Good Hope, Cape Town, Dendron. [Additional material was examined from Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.]

Carabus thoracicus and Carabus fimbriatus are the names given by Thunberg in the same paper to male and female specimens of the present species, a fact which was first noted by

http://species-id.net/wiki/Anthia_maxillosa

Figures 12–17, 29, 33, 37“Cap. bon. sp.” (= Cape of Good Hope).

Carabus maxillosus, Zoological Museum of the University of Copenhagen; Anthia atra, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris.

Easily separated from sympatric species of Anthia by the lack of patterned setae on the pronotum and elytra. Scattered white setae may be present along the elytral margins in unrubbed specimens, but these do not form the distinct bands that are found in the other South African Anthia species.

Body size massive, length of male 42.0-45.0 mm (exclusive of mandibles), length of female 40.5-45.8 mm. Integument black.

Head elongate, prognathous. Mandibles sexually dimorphic and as described for Anthia thoracica except that the left mandible of the male is more markedly recurved. Length of right mandible in male 9.3-12.6 mm. Palpi as in Anthia thoracica except terminal maxillary palpomere more markedly securiform. Antennae as described for Anthia thoracica, including vestiture. Eyes, frons, and vertex as described for Anthia thoracica.

Pronotum cordiform, lateral flanges present but not as broadly expanded as in Anthia thoracica, pronotum still broader than head in both sexes. Form of pronotal base is sexually dimorphic as in Anthia thoracica, with the apical margins of the flanges in male oblique or slightly curved. Pronotum lacking dorsal setae, surface smooth and shining, with scattered small round punctures. Scutellum as in Anthia thoracica. Elytra ovate, markedly convex. Elytral surface sculpture as in Anthia thoracica; vestiture in unrubbed specimens composed of scattered brown setae dorsally and a few scattered white setae laterally, never forming well-defined bands. Apex of elytra rounded in females, slightly more pointed in males. Femora and tibiae as in Anthia thoracica except with scattered stout black setae. Tarsi as described for Anthia thoracica including sexual dimorphism.

Abdomen as in Anthia thoracica except abdominal sterna not as markedly wrinkled laterally. Abdominal sternum VII broadly emarginate at apex in male, broadly rounded at apex in female. Male aedeagus elongate, slender (Figure 29).

Four adult males (7–15) and two adult females (16–17) of Anthia maxillosa (Fabricius), showing variation in male mandible length, in the size of the pronotal flanges in males, and in body size in both sexes. 12 male, Reichsfontein Gate, Richtersveld National Park, Northern Cape Province, RSA, TMSA 13 male, Free State Province, RSA, NMNH 14 male, Namaqualand, Waterval Farm, Northern Cape Province, RSA, TMSA 15 male, Calvinia, Northern Cape Province, RSA, TMSA 16 female, Willowmore, Eastern Cape Province, RSA, TMSA 17 female, Grootmist, North West Province, RSA, NMNH.

Males exhibit considerable variation in the size and length of mandibles and in the size of the basal flange on the pronotum (Figures 7-15). Females also exhibit some variability in overall body size (Figures 16-17).

Unimodal, with greatest activity August-October (Figure 37).

235 pinned adult specimens from the following localities: Republic of South Africa: Eastern Cape Province: 20 miles S Aberdeen, Aberdeen-Beaufort West, Despatch, Grahamstown, Willowmore. Free State Province: Bothaville, no locality specified. Limpopo Province: Grootdraai, Zoutpansberg. Mpumalanga Province: Barberton, Lydenburg. Northern Cape Province: Calvinia, 30 km W Calvinia, De Aar, Duineveld near Stampriet, Kenhardt, Marydale, Nieuwoudtville, Nossob Camp in Kalahari Park, Pofadder, Strydenburg, Van Rhyn’s Pass, Victoria West. Namaqualand region [in Northern Cape]: Braakrivier Mouth, Dikdoorn Farm, Gemsbokvlakte Farm, Harslagkop, Hoekbaai, Katdoringvlei, Klein Kogel Fontein, Kotzesrus, Nababiep, Oograbies, 36 miles E Port Nolloth, Port Nolloth, Quaggasfontein, Rietport Farm, Rooidam Farm, 9 miles S Springbok, 18 km S Springbok, 50 km E Springbok, Springbok-Mesklip, Stallberg Valley, Stinkfontein, 3 km NW Titiesbagi, Vogelklip, Waterval Farm, Wildpaarde Hoek. Richtersveld region [in Northern Cape]: Brakfontein, Buffelsriver valley, Helskloof, Holgat Mouth, 10 W Kuboos, Manganese Mine, Reichsfontein Gate in Richtersveld National Park. North West Province: Grootmist, Haartebeespoort Dam. Western Cape Province: Cape Town, Cedarberg, Koekenaap, Kookfontein, Longkloof, Matiesfontein, Skulpbaai, Touws River, Vanwyksfontein, Zwartskraal farm. [Additional material was examined from Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe.]

There has been considerable confusion in the literature and in collections regarding the identity of this species. Most of the confusion is the result of various authors mistakenly associating the name Carabus maxillosus Fabricius (1781:298) with the name Manticora maxillosa Fabricius (1781:320). These two names were proposed in separate genera and the identities of the taxa to which these names refer are quite clear from the original descriptions. Carabus maxillosus is said to have glabrous elytra and two projecting “lamellae” on the base of the thorax; the term “lamellae” accurately describes the modified basal flanges of the pronotum in males of this species, a feature which places this taxon into the modern carabid genus Anthia. In contrast, Manticora maxillosa is said to have mandibles with a basal tooth and elytra with serrate lateral margins and small tubercles on the disc, features which are not found in Anthia but which are commonly encountered in the modern-day sympatric cicindeline genus Manticora F. These two names appear in other, subsequent works by Fabricius but there is always a clear distinction between Carabus maxillosus with its basal pronotal flanges (

http://species-id.net/wiki/Anthia_cinctipennis

Figures 18–22, 30, 34, 38“Cap de Bonne-Espérance” (= Cape of Good Hope).

Anthia cinctipennis, Anthia limbipennis, and Anthia pachyoma, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris; Anthia hottentota, Hope Department of Entomology, University Museum, Oxford University.

Easily separated from Anthia thoracica by the lack of large round or ovate setal patches on the pronotum, and easily separated from Anthia maxillosa by the presence of a band of white setae along the lateral margins of the elytra. Less easily separated from Anthia circumscripta, although unrubbed specimens of the latter species always have scattered white setae on the lateral flanges of the pronotum. Male genitalia of Anthia circumscripta and Anthia cinctipennis are also diagnostic, with the aedeagus slender in Anthia cinctipennis and stouter and more robust in Anthia circumscripta (Figures 30, 21). Judging by the number of museum specimens examined, Anthia cinctipennis is also much more frequently encountered in RSA than Anthia circumscripta, which is known from relatively few specimens from RSA.

Body size massive, length of male 41.3–43.8 mm (exclusive of mandibles), length of female 43.5-48.8 mm. Integument black.

Head elongate, prognathous. Mandibles sexually dimorphic and as described for Anthia maxillosa except that right mandible of the male has a broad tooth along inner margin. Length of right mandible in male 8.9-10.7 mm. Palpi as in Anthia maxillosa. Antennae as described for Anthia thoracica, including vestiture. Eyes, frons, and vertex as described for Anthia thoracica.

Pronotum as in Anthia maxillosa, no dorsal setae present. Basal flange of pronotum well-developed in males; apex of this flange oblique or slightly curved. Pronotal surface markedly shining, with scattered small round punctures. Scutellum as in Anthia thoracica. Elytra broad, ovate and somewhat more flattened than in other sympatric Anthia species. Elytral sculpture and vestiture as in Anthia thoracica. Femora, tibiae, and tarsi as in Anthia maxillosa. Mesotibiae distinctly broadened at apex in both sexes, with a patch of short reddish setae on expanded portion.

Abdomen as in Anthia maxillosa. Abdominal sternum VII rounded but with a small shallow notch at tip in male, broadly rounded in female. Male aedeagus elongate, slender (Figure 30).

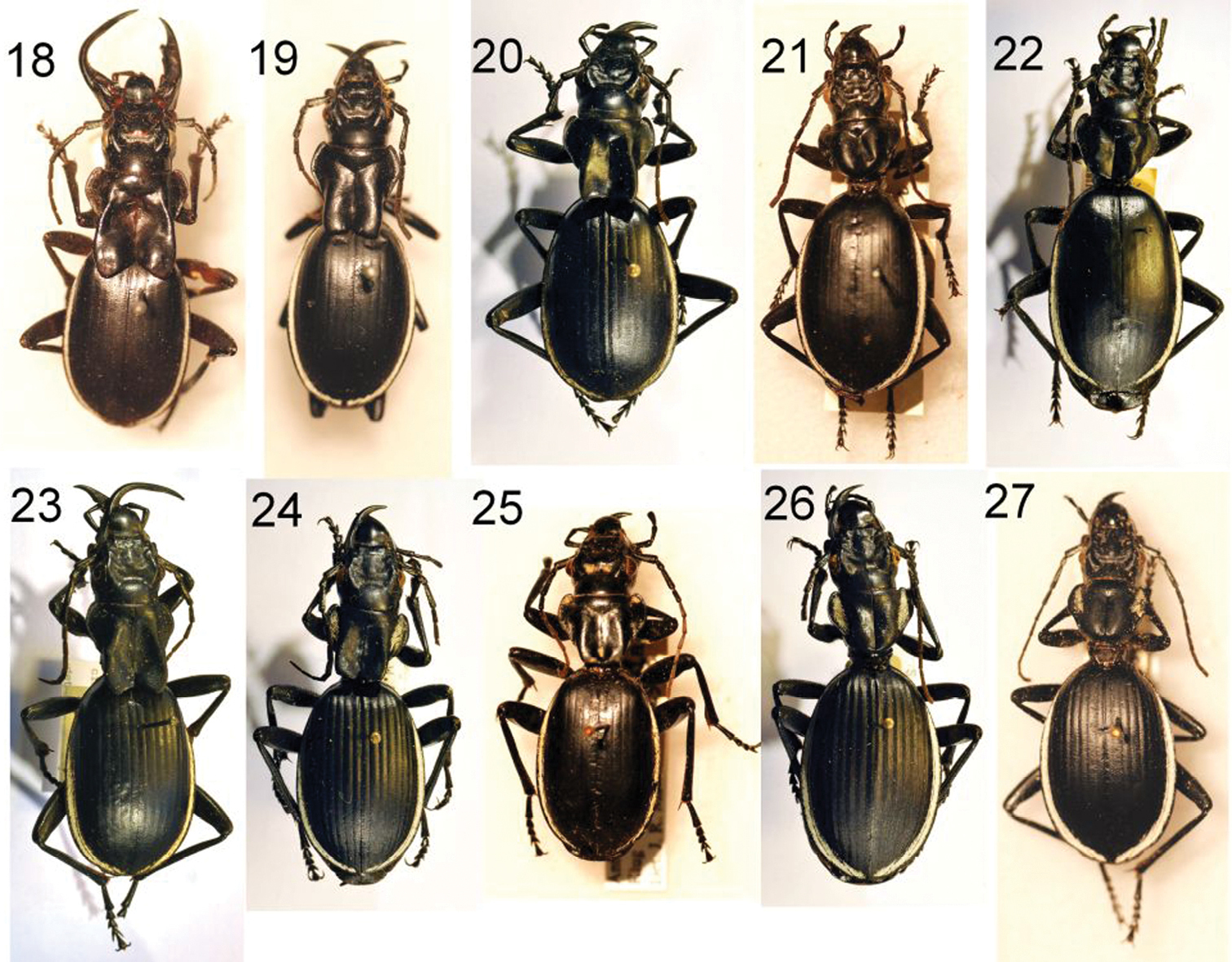

Three adult males (18–20) and two adult females (21–22) of Anthia cinctipennis Lequien, showing variation in male mandible length, in the size of the pronotal flanges in males, and in body size in both sexes. 18 male, Cullinan, Gauteng Province, RSA, NMNH 19 male, Cradock, Eastern Cape Province, RSA, NMNH 20 male, Nauwkluft, Namibia, TMSA 21 female, Grahamstown, Eastern Cape Province, RSA, NMNH 22 female, Langjan Nature Reserve, Limpopo Province, RSA, TMSA. Three adult male (23–25) and two adult females (26–27) of Anthia circumscripta Klug, showing variation in male mandible length, in the size of the pronotal flanges in males, and in body size in both sexes. 23 male, Rehoboth, Namibia, TMSA 24, male, Namib Desert, Namibia, TMSA 25 male, Zimbabwe, NMNH 26 Namib Desert, Namibia, TMSA 27 Ganab, Namibia, NMNH.

Males exhibit considerable variation in the size and length of mandibles and in the size of the basal flange on the pronotum (Figures 18-20). Females also exhibit some variability in overall body size (Figure 21-22).

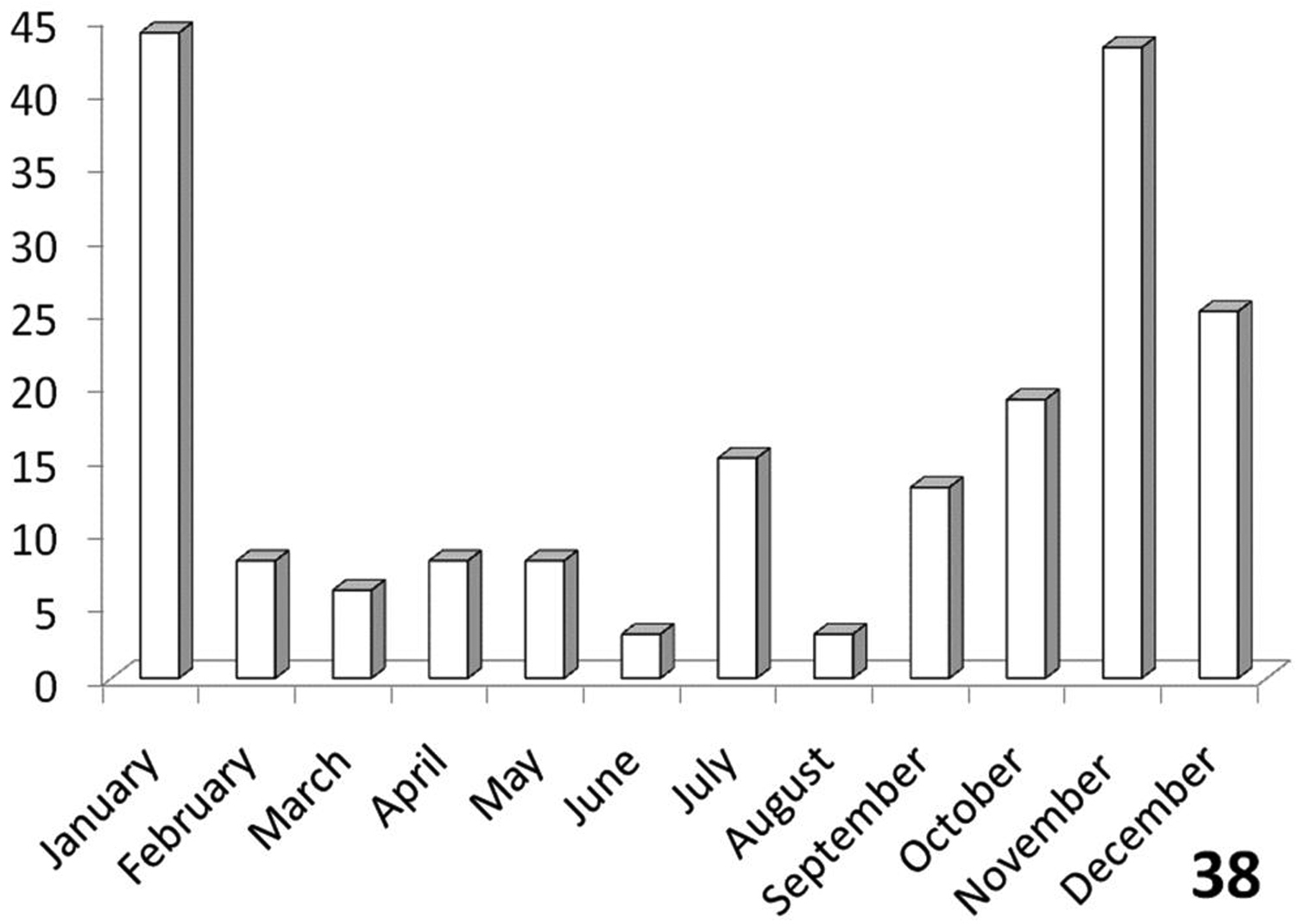

Bimodal (Figure 38), with an activity peak from September-January in central and northeastern RSA (Free State, Gauteng, Limpopo, and Mpumalanga Provinces) and another, smaller activity peak in July in the Kalahari Gemsbok Park and other areas in Northern Cape Province.

131 pinned adult specimens from the following localities: Republic of South Africa: Eastern Cape Province: Cradock, Graaff Reinet, Grahamstown, 14 miles E Middelburg. Free State Province: Bothaville, Reddersburg, Smithfield. Gauteng Province: Bronkhorstspruit, Cullinan, Johannesburg, Pretoria, Rhenosterpoort, Valhalla, Zoutpan Pta. KwaZulu-Natal Province: Elandskraal, “E. Zululand.” Limpopo Province: Dzombo Plots, Gravelotte, Grootdraai, Langjan Nature Reserve, Louis Trichardt, Messina, Nyandu Sandveld, Nylsvley, Penge, 20-26 km NE of Pietersburg, Pietersburg, Shilouvane, Warm Baths, Woodbush, Zoutpansberg. Mpumalanga Province: Barberton, Loskop, Lydenburg, Pilgrim’s Rest, Satara, Skukuza, Waterval, Waterval Pass. Northern Cape Province: Kimberley, Marydale, Richmond, 47 miles N of van Rhynsdorp, Kalahari Gemsbok Park: Farm Mara, 25 km S of Mata Mata, Mata Mata, Twee Rivieren. [Additional material was examined from Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.]

http://species-id.net/wiki/Anthia_circumscripta

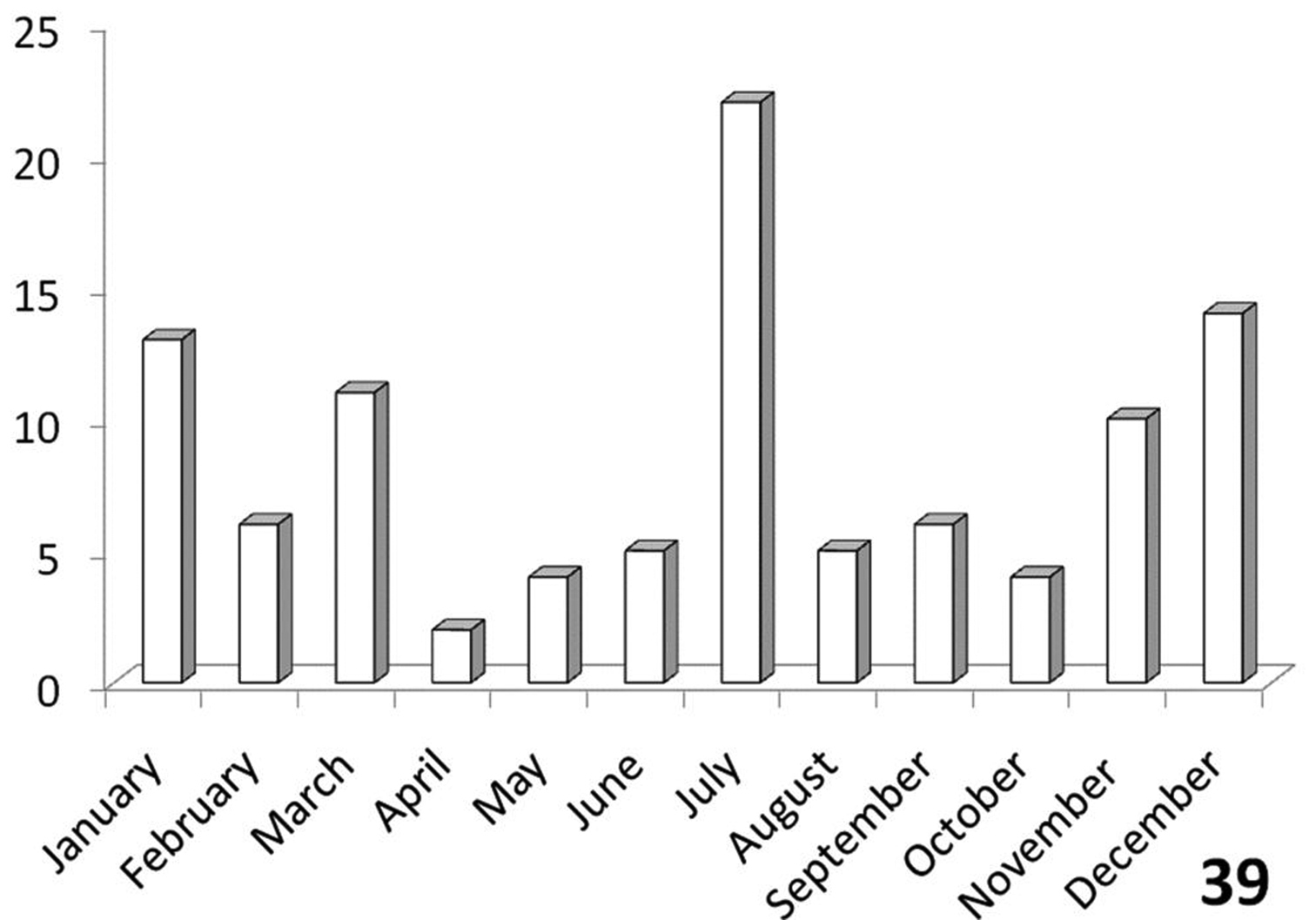

Figures 23–27, 31, 35, 39“Tette” (= Tete, Mozambique).

Anthia circumscripta, Museum für Naturkunde, Humboldt-Universität, Berlin.

Unrubbed specimens have scattered areas of white setae on the lateral flanges of the pronotum, which is a diagnostic feature for this species. Rubbed specimens resemble Anthia cinctipennis but males can be separated by the structure of the male genitalia which are slender in Anthia cinctipennis and stouter and more robust in Anthia circumscripta (Figures 30, 31). This species is known from relatively few specimens from RSA; however, it is represented in museum collections by large series from Botswana and Namibia, where it is evidently more frequently collected.

Body size massive, length of male 41.3-48.0 mm (exclusive of mandibles), length of female 42.6-50.4 mm.

Head elongate, prognathous. Mandibles larger in males than in females. Length of right mandible in male 7.4-8.6 mm. Palpi as in Anthia maxillosa. Antennae, eyes, frons, and vertex as in Anthia thoracica.

Pronotum cordiform, shape as in Anthia cinctipennis except that the basal flanges in male are often much smaller; apical margin of flanges transverse, with distinct emargination at apex of both flanges. Lateral flanges of pronotum with a more-or-less distinct patch of scattered short white reclinate setae. Pronotal surface sculpture smooth and shining, markedly punctate with large round punctures. Scutellum as in Anthia thoracica. Elytra elliptical-oval, convex medially. Vestiture as in Anthia thoracica. Each elytron with 8 distinct longitudinal striate interneurs, which may be feebly to somewhat markedly impressed; each interneur with a row of small round punctures, remainder of surface with scattered small round punctures. Legs as in Anthia maxillosa, mesotibiae modified in both sexes as described for Anthia cinctipennis.

Abdomen as in Anthia thoracica. Male aedeagus stout, robust (Figure 31).

Dorsal view of abdominal apex, with aedeagus extended 28 Anthia thoracica (Thunberg) 29 Anthia maxillosa (Fabricius) 30 Anthia cinctipennis Lequien 31 Anthia circumscripta Klug.

Males exhibit considerable variation in the size and length of mandibles and in the size of the basal flange on the pronotum (Figures 23-25). Females also exhibit some variability in overall body size (Figures 26-27).

Distinctly bimodal (Figure 39), with populations from the Namib and Kalahari deserts having a July activity peak while populations from eastern Botswana, Zimbabwe and the few RSA records have an activity peak in November-March. Figure 39 shows records from throughout southern Africa, since only a very few specimens from RSA were available for study.

2 pinned adult specimens from the following localities: Republic of South Africa: Free State Province: Golden Gate. KwaZulu-Natal Province: Maritzburg. [Additional material was examined from Botswana, Kenya, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe].

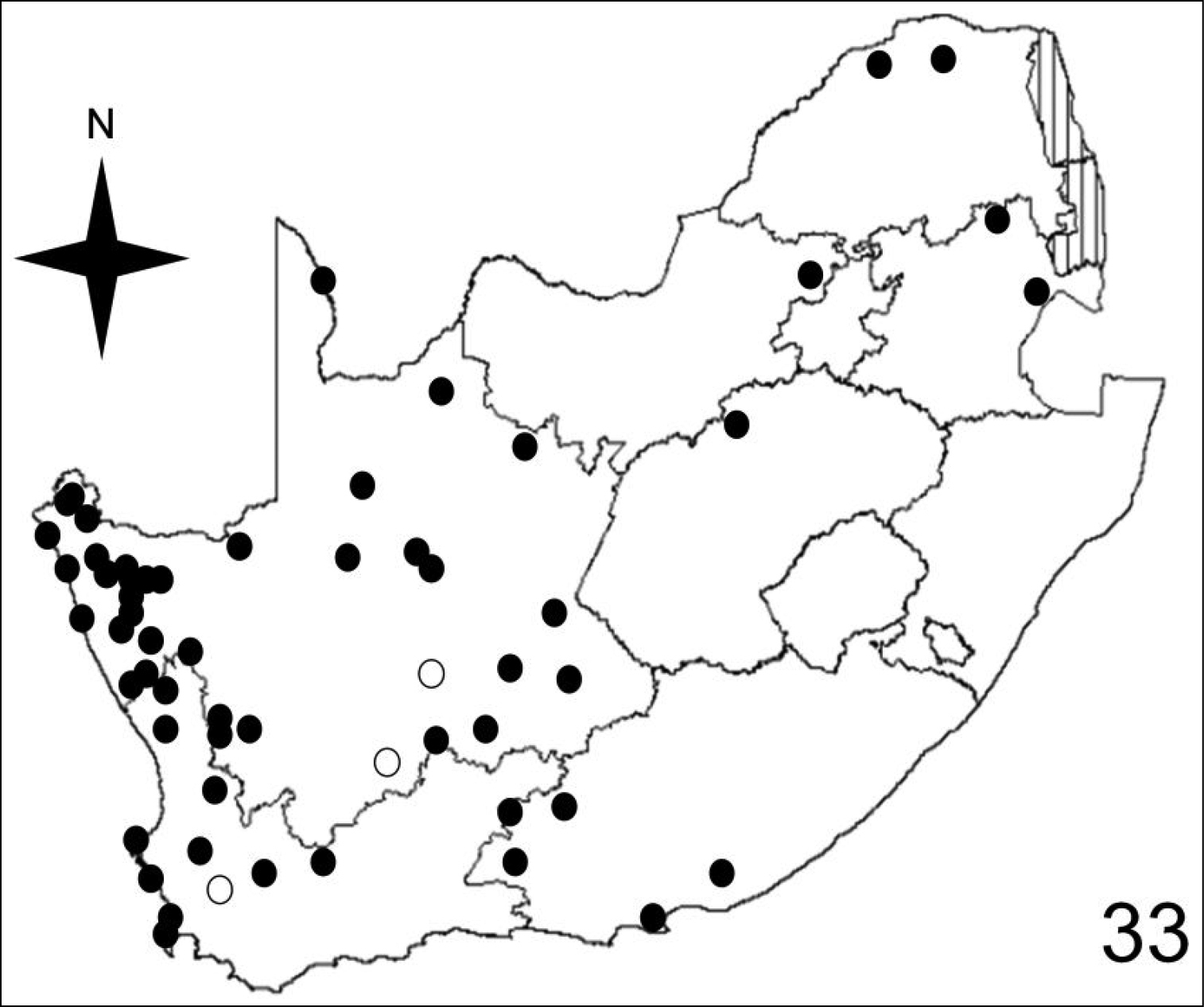

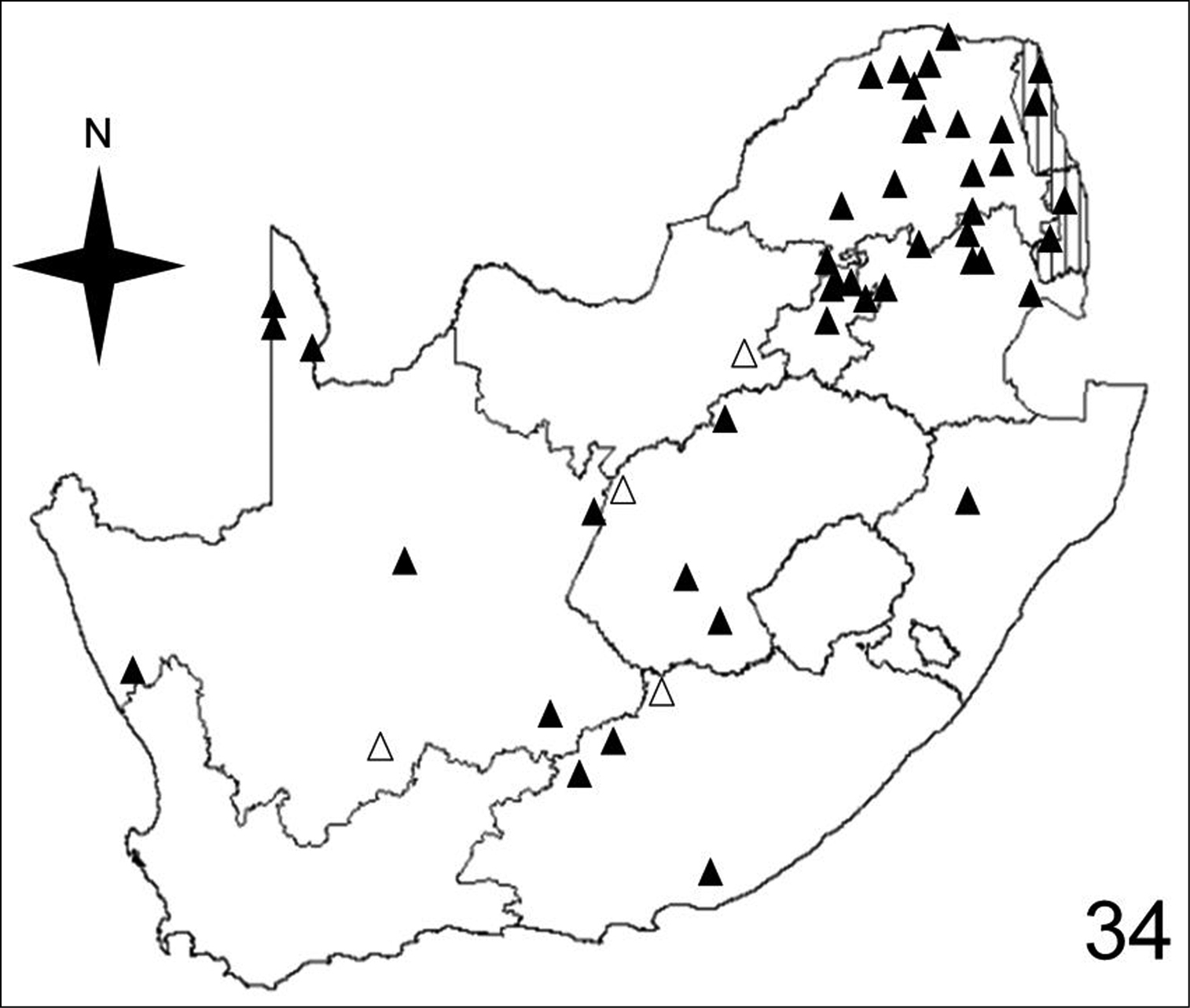

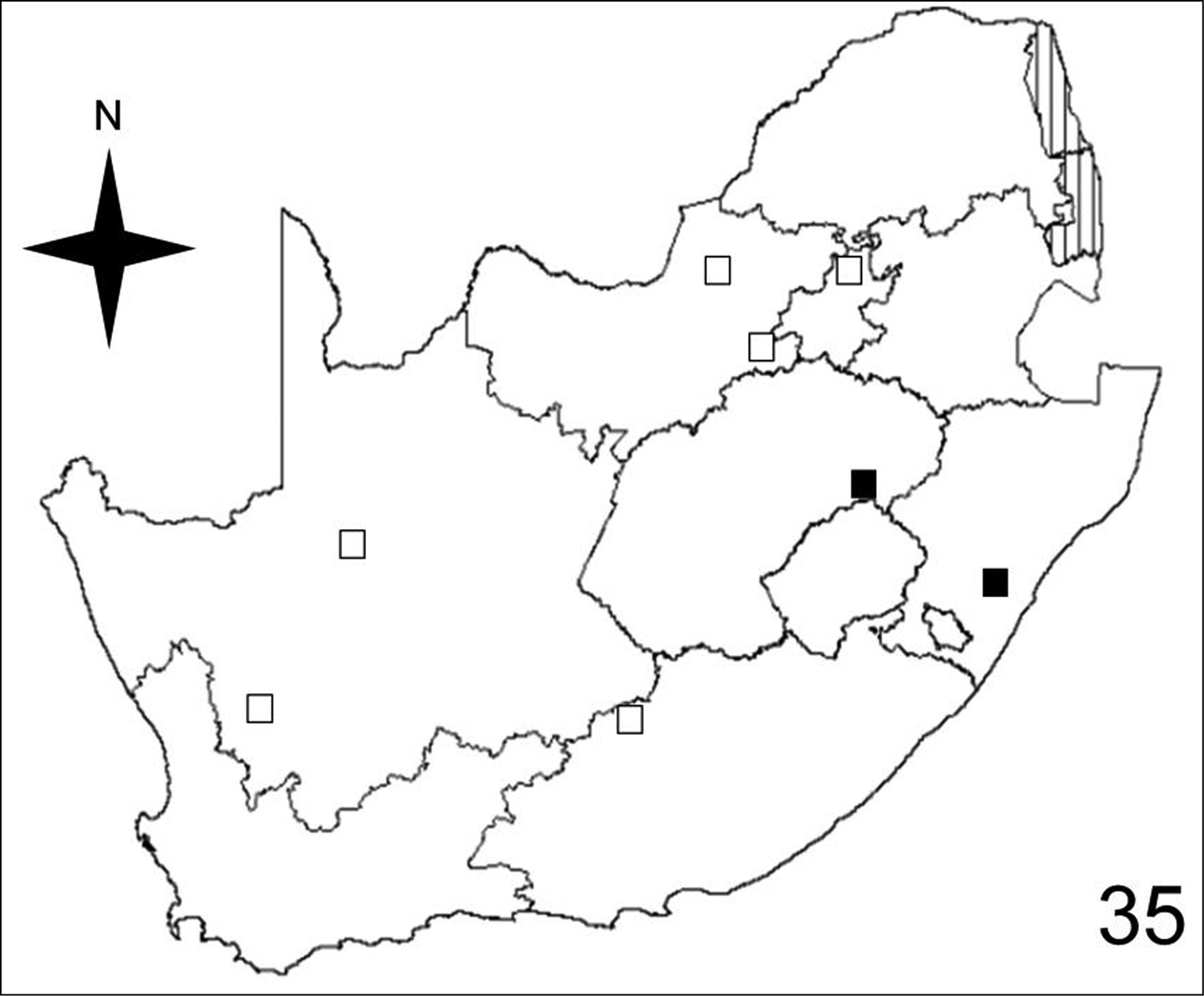

Figures 32–35 illustrate the distribution of species of Anthia in the Republic of South Africa based on museum specimen records, literature records, and our own recent collections. The individual species show markedly different patterns of distribution. Anthia thoracica has been most frequently collected in the northern and eastern portions of the country (Figure 32), particularly in Gauteng, Limpopo, and Mpumalanga Provinces. Anthia maxillosa has been most frequently collected in the west (Figure 33), particularly the Western Cape and Northern Cape Provinces. Anthia cinctipennis has a distribution pattern somewhat similar to that of Anthia thoracica (Figure 34), with a high concentration of records in Gauteng, Limpopo, and Mpumalanga Provinces, while Anthia circumscripta appears to be rare everywhere in the Republic of South Africa (Figure 35), with very few literature or specimen records. As noted above, Anthia circumscripta has been collected in much greater numbers in Botswana and Namibia, and forms a characteristic part of the Anthia fauna in both the Kalahari and Namib deserts.

Distribution map showing collecting localities of museum specimens of Anthia thoracica (Thunberg) in the Republic of South Africa. Dark stars indicate specimens that we personally examined; white stars indicate literature records.

Distribution map showing collecting localities of museum specimens of Anthia maxillosa (Fabricius) in the Republic of South Africa. Dark circles indicate specimens that we personally examined; white circles indicate literature records.

Distribution map showing collecting localities of museum specimens of Anthia cinctipennis Lequien in the Republic of South Africa. Dark triangles indicate specimens that we personally examined; white triangles indicate literature records.

Distribution map showing collecting localities of museum specimens of Anthia circumscripta Klug in the Republic of South Africa. Dark squares indicate specimens that we personally examined; white squares indicate literature records.

Adults of species of Anthia are widely distributed throughout the Republic of South Africa (Figures 32–35) and have been collected in twelve of the seventeen terrestrial ecoregions recognized by

Adults of Anthia thoracica have been collected in eight of the seventeen terrestrial ecoregions recognized by

Adults of Anthia maxillosa have been collected in eight of the seventeen terrestrial ecoregions recognized by

Adults of Anthia cinctipennis have been collected in eight of the seventeen terrestrial ecoregions recognized by

Adults of Anthia circumscripta have been collected in three of the seventeen terrestrial ecoregions recognized by

To compare these findings across the four Anthia species and the seventeen terrestrial ecoregions in the Republic of South Africa, we used the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (

Percentage of collecting sites for each of four species of Anthia in each of the seventeen terrestrial ecoregions in the Republic of South Africa.

| Terrestrial Ecoregion | % collecting localities for Anthia thoracica | % collecting localities for Anthia maxillosa | % collecting localities for Anthia cinctipennis | % collecting localities for Anthia circumscripta |

| Maputaland Coastal Forest Mosaic | 4.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| KwaZulu–Cape Coastal Forest Mosaic | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Knysna-Amatole Montane Forests | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Zambezian and Mopane Woodlands | 19.7 | 0.0 | 10.6 | 0.0 |

| Southern Africa Bushveld | 13.1 | 3.4 | 25.5 | 0.0 |

| Kalahari Acacia Woodlands | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Highveld Grasslands | 36.1 | 5.2 | 36.2 | 37.5 |

| Drakensburg Montane Grasslands, Woodlands, and Forests | 0.0 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 25.0 |

| Drakensburg Alti-Montane Grasslands and Woodlands | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Maputaland-Pondoland Bushland and Thickets | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.0 |

| Lowland Fynbos and Renosterveld | 4.9 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Montane Fynbos and Renosterveld | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Albany Thickets | 8.2 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Kalahari Xeric Savanna | 0.0 | 5.2 | 14.9 | 0.0 |

| Nama Karoo | 11.5 | 25.9 | 6.4 | 37.5 |

| Succulent Karoo | 0.0 | 48.3 | 2.1 | 0.0 |

| Southern African Mangroves | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Spearman rank correlation coefficients from pairwise comparisons of the columns of values for each species in Table 1.

| Anthia thoracica | Anthia maxillosa | Anthia cinctipennis | |

| Anthia maxillosa | 0.319655 | ||

| Anthia cinctipennis | 0.441241 | 0.50938 | |

| Anthia circumscripta | 0.347861 | 0.444142 | 0.492868 |

Percentage of collecting sites for each of four species of Anthia in each of the ten veld types in the Republic of South Africa.

| Veld Type | % collecting localities for Anthia thoracica | % collecting localities for Anthia maxillosa | % collecting localities for Anthia cinctipennis | % collecting localities for Anthia circumscripta |

| Desert | 0.0 | 14.3 | 2.1 | 0.0 |

| Succulent Karoo | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Karoo | 11.3 | 63.1 | 18.8 | 37.5 |

| Bushveld | 51.6 | 10.7 | 45.8 | 12.5 |

| Scrubby mixed Grassveld | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sweet Grassveld | 9.7 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 0.0 |

| Mixed Grassveld | 9.7 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.0 |

| Sour Grassveld | 9.7 | 1.2 | 29.2 | 50.0 |

| Forest and Scrubforest | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Fynbos | 8.1 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Spearman rank correlation coefficients from pairwise comparisons of the columns of values for each species in Table 3.

| Anthia thoracica | Anthia maxillosa | Anthia cinctipennis | |

| Anthia maxillosa | 0.347412 | ||

| Anthia cinctipennis | 0.831126 | 0.431049 | |

| Anthia circumscripta | 0.693726 | 0.401331 | 0.802852 |

Adults of Anthia species are likewise broadly distributed across the various veld types or large-scale vegetation communities recognized by

Adults of Anthia thoracica have been collected in six of the ten veld types: Bushveld (51.6% of collecting sites); Karoo (11.3% of collecting sites); Sweet Grassveld (9.7% of collecting sites); Mixed Grassveld (9.7% of collecting sites); Sour Grassveld (9.7% of collecting sites); and Fynbos (8.1% of collecting sites).

Adults of Anthia maxillosa have been collected in seven of the ten veld types: Karoo (63.1% of collecting sites); Desert (14.3% of collecting sites); Bushveld (10.7% of collecting sites); Fynbos (7.1% of collecting sites); Succulent Karoo (2.4% of collecting sites); Sweet Grassveld (1.2% of collecting sites); and Sour Grassveld (1.2% of collecting sites).

Adults of Anthia cinctipennis have been collected in six of the ten veld types: Bushveld (45.8% of collecting sites); Sour Grassveld (29.2% of collecting sites); Karoo (18.8% of collecting sites); Desert (2.1% of collecting sites); Sweet Grassveld (2.1% of collecting sites); Mixed Grassveld (2.1% of collecting sites).

Adults of Anthia circumscripta have been collected in just three of the ten veld types: Sour Grassveld (50%); Karoo (37.5%); and Bushveld (12.5%).

We again applied the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (

The histograms in Figures 36-39 summarize dates of collection of museum specimens of Anthia species across all years. These charts suggest that individual species of the genus Anthia exhibit marked seasonality in the timing of adult emergence and in the timing of adult activity patterns, as noted previously by

Activity patterns of adults of Anthia thoracica (Thunberg) in South Africa, based on museum specimen records and summed by month across all years. The vertical axis indicates numbers of specimens.

Activity patterns of adults of Anthia maxillosa (Fabricius) in South Africa, based on museum specimen records and summed by month across all years. The vertical axis indicates numbers of specimens.

Activity patterns of adults of Anthia cinctipennis Lequien in South Africa, based on museum specimen records and summed by month across all years. The vertical axis indicates numbers of specimens.

Activity patterns of adults of Anthia circumscripta Klug in South Africa, based on museum specimen records and summed by month across all years. The vertical axis indicates numbers of specimens.

Males of species of Anthia in the Republic of South Africa often have enlarged and elongated mandibles as well as distinctive flanges on the base of the pronotum (Figures 3–8, 12–15, 18–20, 23–25). Both mandibles and flanges come in large, small, and intermediate sizes, and in general, larger-bodied males appear to have larger mandibles and pronotal flanges than smaller males. We were interested in determining whether mandible and pronotal flange size of these beetles scale isometrically (mandible and flange size increases at the same rate as body size) or allometrically (mandible and flange size increase at a rate disproportionately greater than body size). We measured three variables, right mandible length, pronotal length (from apex to base of flange), and elytral width (a surrogate measure of body size, measured at the widest point with the elytra fully closed in a natural position) for all male specimens of these four Anthia species in the NMNH collection. For Anthia thoracica, we observed only a very weak correlation between elytral width and mandible length (R2 = 0.61) and between elytral width and pronotal length (R2 = 0.63) using standard linear regression. Both R2 values improved with the use of a polynomial (x2) function in the regression, to 0.67 and 0.75, respectively. The improved fit with the polynomial function and the generally low R2 values from the standard linear regression suggests that both mandible size and pronotal flange size scale non-linearly with respect to body size in this species. In the other three species, mandible length and pronotal length were very poorly correlated with elytral width (R2 values ranging from 0.04 to 0.27), suggesting that mandible and pronotal flange size is not correlated with elytral width.

South African Anthiini as vectors for Cyaneolytta larvae (Coleoptera: Meloidae)Many large-bodied Carabidae in southern Africa have been documented as serving as vectors for the phoretic larvae of species in the blister beetle genus Cyaneolytta Péringuey (

Anthia thoracica is one of two species in the genus Anthia recorded from Kruger National Park, a large and well-known conservation area which is located in eastern Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces, South Africa (

Occurrences within Kruger National Park: Specimens of Anthia thoracica have been collected at the following localities within Kruger National Park: Malelane, Numbi Gate, Pumbe Sands, Shingwedzi, Skukuza, and Stolsnek. In addition, the senior author and associates have recently encountered this species on sand and gravel roads in the vicinity of the Pretoriuskop and Skukuza rest camps, and in the N’waswitshaka Research Camp at Skukuza.

Associated ecological communities:

Terminalia sericea Burchell woodland near Pretoriuskop, Kruger National Park, habitat for Anthia thoracica (Thunberg) and Termophilum burchelli (Hope).

Co-occurrence with allied species: We collected adults of Anthia thoracica in association with adults of of Termophilum burchelli (Hope), Termophilum homoplatum (Lequien), Termophilum massilicatum (Guérin), and Cypholoba graphipteroides (Guérin) (all Carabidae: Anthiini). Adults of Termophilum homoplatum and Termophilum massilicatum were found primarily in the open savanna areas extending northward area from Skukuza to Satara (Figure 42), while adults of Termophilum burchelli and Cypholoba graphipteroides were found in denser thickets and woodlands from Pretoriuskop in the south along the banks of the Sabie River to Skukuza (Figures 40-41). The related species Anthia cinctipennis Lequien has also been collected in Kruger National Park, with records from Skukuza, Satara, and the Nyandu Sandveld (Figure 42).

Acacia nigrescens Oliver – Combretum apiculatum Sonder woodland near Skukuza, Kruger National Park, habitat for Anthia thoracica (Thunberg), Termophilum homoplatum (Lequien), and Cypholoba graphipteroides (Guérin).

Open grassland savanna near Satara, Kruger National Park, habitat for Anthia cinctipennis Lequien, Termophilum homoplatum (Lequien), and Termophilum massilicatum (Guérin).

Activity period: Specimen records from South Africa (Figure 36) indicate that collections of Anthia thoracica have occurred between September and May, with a peak in November-December. Emergence of adults of Anthia thoracica appears to be triggered by the onset of seasonal rains (

Weather and climate: Adult activity patterns of Anthia thoracica appear to be markedly influenced by weather and climatic conditions (

Defensive behaviors: Adults of Anthia thoracica spray copious amounts of highly concentrated formic acid from their pygidial glands when disturbed (

Mimicry: Anthia thoracica and the sympatric species Termophilum homoplatum (Lequien) share similar color patterns which include large round or ovate eyespots, a black, shining dorsal integument, and a narrow white linear band along the outer margin of the elytra (Figures 1, 2). In Anthia thoracica, the eyespots are on the pronotum while in Termophilum homoplatum the eyespots are on the base of the elytra. Both species occur in similar habitats at the same times of year and exhibit similar fast walking behaviors. Both species are chemically defended, with the capacity to spray similar combinations of highly concentrated formic acid and other acidic compounds from the pygidial glands (Scott, Hepburn, and Crewe 1975).

Prey species: Adults of Anthia thoracica in captivity showed few preferences regarding prey items and consumed a wide range of prey species, including representatives of the following orders and families: Coleoptera: Carabidae, Cerambycidae, Curculionidae, Scarabaeidae, Tenebrionidae. Hemiptera: Cicadidae, Cydnidae. Hymenoptera: Formicidae. Isoptera: Termitidae. Lepidoptera: Arctiidae, Geometridae, Noctuidae, Saturniidae. Orthoptera: Acrididae. These insects were captured at lights at night in the N’waswitshaka Research Camp and fed to the live Anthia thoracica.

Foraging behavior: Adults of Anthia thoracica exhibit a rapid walking behavior which appears to serve multiple functions: foraging for food, detection of mates, and dispersal of adults. In captivity, this behavior was often noticed in adults of Anthia thoracica which had not been fed for several hours.

Prey detection: Adults of Anthia thoracica were observed to move and vibrate their antennae in the presence of potential prey items, suggesting that chemical cues may form an important part in the detection and recognition of prey items.

Predatory behaviors: Adults of Anthia thoracica seized prey using their mandibles and rapidly crushed prey items with the mandibular bases, using the labial and maxillary palpi to hold and manipulate the prey item. Liquid contents of prey and soft tissues were consumed whole while heavily sclerotized parts and appendages (legs, wings) were discarded.

Drinking: Captive adults of Anthia thoracica were observed drinking from wet cotton balls which we provided in their containers; in drinking, the adult beetle stands perpendicular to the water source, the ventral surface of the head is pressed against the wet cotton and water is then taken directly into the buccal cavity.

Antennal cleaning: Adults of both sexes of Anthia thoracica have an antennal cleaning notch along the inner margin of the protibiae. Adults were observed drawing the antennae through this notch after feeding, after handling by humans, and after being introduced into a new captive holding chamber.

Concluding RemarksWe hope that the identification materials presented in this paper will be of assistance to entomologists, field biologists, national park managers, and others who want to identify specimens of Anthia species in the Republic of South Africa. We also hope that this paper helps to spark additional interest in these large and spectacular members of the South African insect fauna. Species of the genus Anthia and related genera are large, common, and conspicuous members of savanna and woodland ecosystems throughout southern and eastern Africa. Our understanding of the natural history of this group is limited at present and further investigations of the life history, immature stages, and biology of these beetles are clearly needed. The genus Anthia and its relatives provide excellent opportunities for studying the evolution of chemical defenses, aposematic coloration, and Müllerian mimicry. Anthia and its relatives also have attributes which suggest they may be excellent candidates for inclusion in monitoring programs that track ecosystem condition or ecological integrity in southern Africa. Adult activity patterns of Anthia species closely track a variety of environmental and climatological variables (

We dedicate this paper to the late P. Basilewsky in recognition of his numerous significant contributions to the taxonomy of African Carabidae. For assistance with fieldwork, we thank F. Venter, V. Ndlovu, J. Baloyi, O. Sithole, A. Manganyi, P. Khoza, and T. Khoza of South African National Parks. For additional field assistance we thank R. D. Mawdsley, as well as J. du G. Harrison and his family. For assistance with visits to museum collections, we thank A. Newton and M. Thayer (FMNH), G. Zambatis (KNPC), R. Staals and B. Grobbelaar (SANC), and J. du G. Harrison and Ruth Müller (TMSA).