(C) Neucir Szinwelski. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

We tested the value of ethanol fuel as a killing solution in terms of sampling efficiency (species richness and accumulated abundance) and DNA preservation of Ensifera ground-dwelling specimens. Sampling efficiency was evaluated comparing abundance and species richness of pitfall sampling using 100% ethanol fuel, with two alternative killing solutions. We evaluated the DNA preservation efficiency of the killing solutions and of alternative storage solutions. Ethanol fuel was the most efficient killing solution, and allowed successful DNA preservation. This solution is cheaper than other preserving liquids, and is easily acquired near field study sites since it is available at every fuel station in Brazil and at an increasing number of fuel stations in the U.S. We recommend the use of ethanol fuel as a killing and storage solution, because it is a cheap and efficient alternative for large-scale arthropod sampling, both logistically and for DNA preservation. For open habitat sampling with high day temperatures, we recommend doubling the solution volume to cope with high evaporation, increasing its efficacy over two days.

Killing solutions, Molecular tools, Taxonomy, Large-scale fieldwork, Brazil

Several sampling techniques are used to assess biodiversity of different animal species (

Pitfall traps are a good alternative for collecting ground-dwelling arthropods (

Regarding methodological necessities in pitfall sampling, a good killing solution should minimize evaporation, as far as many pitfall trap regimes check traps every 2 weeks or more. A good solution should not be toxic to the researcher nor environmentally harmful. Regarding sampling efficiency, a good solution should kill quickly so as to reduce the escape of specimens. In addition, the trap solution cannot be prohibitively expensive, and must be readily available.

Finding a solution that meets all of these specifications is not easy. Many types of solutions have been used and tested, for example water and detergent, which is inexpensive but accelerates the decomposition of tissues and genetic material (

It has been shown that at concentrations higher than 95%, commercial alcohol preserves DNA (

In Brazil, ethanol fuel and commercial alcohol have some differences. While the alcoholic concentration (92.6 to 93.8%) and the amount of water (6.2 to 7.4%) varies in ethanol fuel, in commercial alcohol the alcoholic concentration (92.8%) and the amount of water (7.2%) is fixed. The largest difference is, however, the quantity of gasoline present in ethanol fuel (up to 30 milliliters per liter), that is absent in commercial alcohol (BR0029 2011). In the United States, the highest concentration of ethanol fuel includes 85% ethanol and 15% gasoline (

In this study, we tested the value of ethanol fuel as a pitfall trap killing solution in terms of sampling efficiency (richness and abundance) and DNA preservation of Ensifera ground-dwelling specimens, comparing 100% ethanol fuel with two alternative killing solutions.

Material and methods Sampling efficiencyField sampling site

To evaluate sampling efficiency, we conducted field sampling in a primary Atlantic Forest reservoir, the Iguaçu National Park, in Foz do Iguaçu municipality (25°32'S, 54°35'W, 195m above sea level), Paraná State, in January 2010. The vegetation is mostly tropical semideciduous forest and Araucaria forest, within the Atlantic Forest biome (

Sampling design

We compared the efficiency of 100% ethanol fuel pitfall killing solution (Solution 1) for ground-dwelling Orthoptera, against the conventional killing solution, comprised of 80% commercial alcohol (80°GL) + 10% glycerin (P.A) + 10% formaldehyde (P.A) (

For this comparison, we designed the following field experiment. We established a transect of 5km, starting at a distance of 100m from the forest’s edge. At the beginning of the transect a set of five pitfall traps, containing one of the three killing solutions chosen randomly, were placed perpendicularly to the transect, 2m apart from one another. After the next 30m on the transect, we placed the second set with a different, randomly chosen, killing solution. After another 30m along the transect, we placed the third set, with the third killing solution. After an additional forty meters we began the procedure again, and repeated it a total of 50 sampling stations. In summary each sampling station contained five pitfall traps with each of the three killing solutions, for a total sampling effort of 750 pitfall traps. Traps consisted of polyethylene vials, 20cm in diameter and 22cm deep, filled with 500ml of killing solution. After 48 hours, specimens were removed from the the traps, identified and stored in ethanol fuel, after gathering the data.

Data analysis

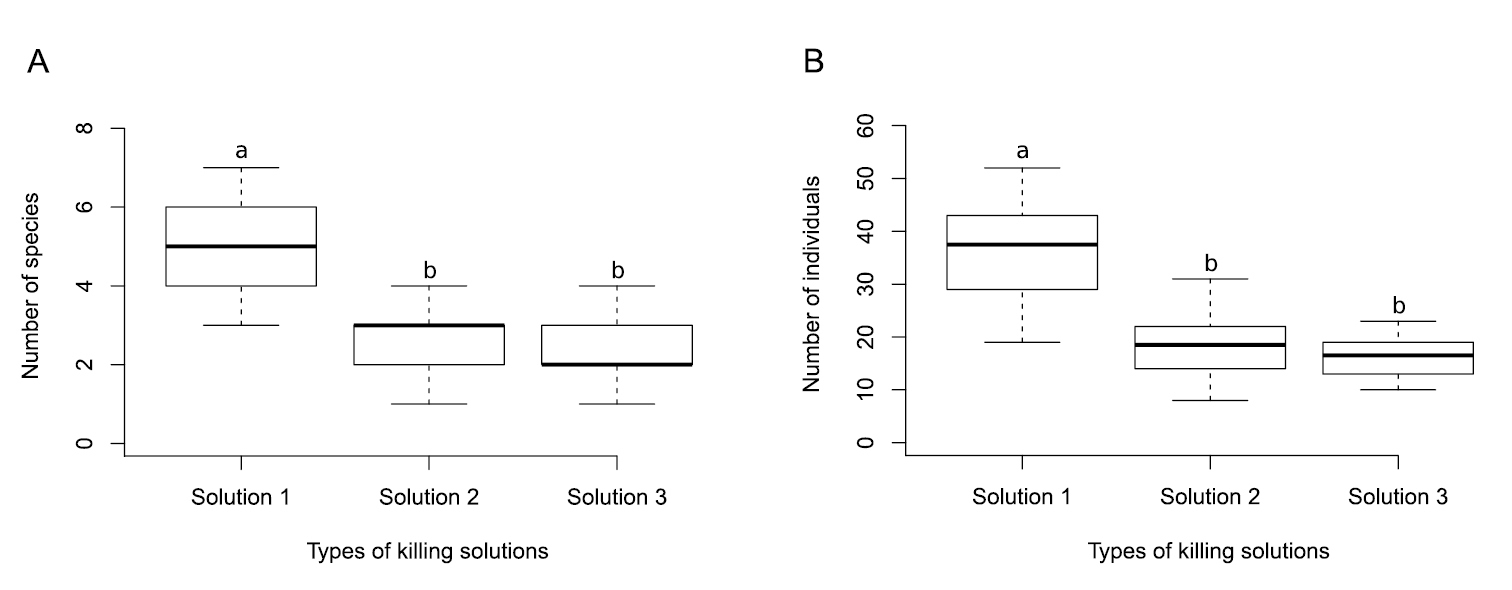

To evaluate sampling efficiency of ethanol fuel as a pitfall killing solution, we compared cricket species richness and accumulated abundance (= total number of individuals per pitfall set) among the three solutions. Each pitfall set was considered one sampling unit, rendering 150 replicates. We performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), adjusting generalized linear models (GLMs) with Poisson error distribution, correcting for over- or under-dispersion using quasi-Poisson when necessary. We considered cricket species richness and accumulated abundance in each set of five pitfall traps as response variables (n = 150), and the type of killing solution as the explanatory factor. We used contrast analyses to evaluate effect differences among the kinds of solution, simplifying the complete models by amalgamating non-significantly different factor levels (

Killing and storage

To test the DNA preservation properties of each pitfall killing solution, we placed each of 18 living cricket specimens of Gryllus sp. (not identified) into one of the three pitfall killing solutions, totaling six specimens per solution. As a control, we separately placed another six crickets into undiluted commercial alcohol (92.8°GL), which is considered a good preservative of DNA (

To evaluate the efficiency of ethanol fuel as a storage solution, we stored each cricket specimen, after 48 hours in the killing solution, in one of two storage solutions: undiluted commercial alcohol (92.8°GL) or undiluted ethanol fuel. To test the effect of time and type of storage solution on the DNA preservation efficiency, we removed a third leg off each cricket after 15 days, and a fourth leg after 30 days in the storage solution.

We evaluated efficiency of DNA preservation for the 24 crickets used in the above procedure. Each set of six individuals was submitted to one of four different killing solutions, and each individual provided two samples (= legs) for DNA extraction before storage (24 and 48 hours in the killing solution). Individuals from each killing solution were transferred to either commercial alcohol or ethanol fuel for storage, providing three replicates (individuals) per storage solution, and two further samples (= legs) per individual, 15 and 30 days in the storage solution. All specimens were maintained at room temperature for 30 days.

DNA extraction

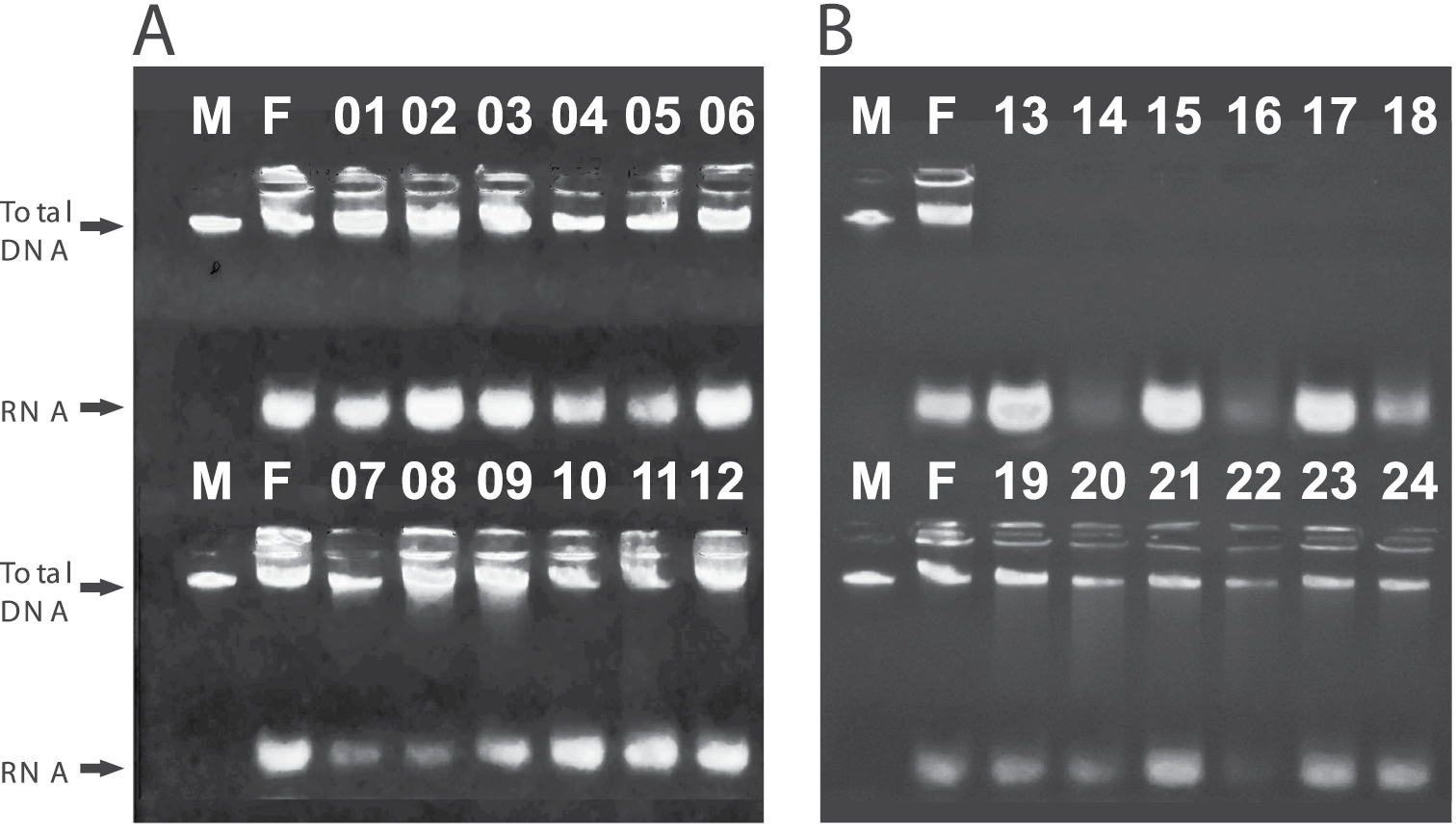

Total DNA was isolated from each individual using the protocol described in

DNA extractions were verified via agarose gel (0.8%) electrophorese, prepared and run in 1X TBE Buffer, stained with ethidium bromide and viewed under UV light. The quality of the extractions was checked by comparison with the extract made from fresh material (specimens that were killed by freezing, with immediate DNA extraction). Extractions from fresh material presented two bands, the first clearly marked and bright, corresponding to genomic DNA and the second smaller, more opaque, corresponding to RNA. We considered DNA as properly preserved when we detected a well-defined single band of DNA without apparent trawlers.

Results Sampling efficiencyWe collected 3, 528 individuals of 14 species from four different families of Orthoptera, following the classification of

Boxplot showing sampling efficiency of different kinds of pitfall traps' killing solution. Traps with Solution 1 (100% ethanol fuel) captured more species and individuals than Solution 2 (80% commercial alcohol (80°GL) + 10% glycerin (P.A) + 10% formaldehyde (P.A)) and Solution 3 (90% commercial alcohol (80°GL) + 10% glycerin (P.A)). A Total number of species per pitfalls’ set. B Total number of individuals per pitfalls’ set. Different lower case letters correspond to significant differences between killing solution levels, evaluated through contrast analyses.

Table 1 indicates that both solution 1 and solution 3 were efficient in preserving DNA and are appropriate for use as killing solutions in pitfall traps that must remain in the field for up to 48 hours, with no visible damage to DNA. In addition, these samples can be stored at room temperature for up to 30 days in either commercial alcohol or ethanol fuel. On the other hand, our results suggest that just 24 hours in solution 2 (commercial alcohol + glycerin + formaldehyde) are enough to destroy the DNA of the samples (Figure 2).

Success (yes) or failure (no) of DNA extractions after different periods (Time in the solution) in Killing solution (Pitfall: 24h and 48h) and in storage solution (C.A. and E.F.: 15 and 30 days). C.A. = undiluted commercial alcohol (92.8°GL); E.F. = undiluted ethanol fuel; Solution 1 = E.F.; Solution 2 = 80% commercial alcohol (80°GL) + 10% glycerin (P.A.) + 10% formaldehyde (P.A.); Solution 3 = 90% commercial alcohol (80°GL) + 10% glycerin (P.A.). All material was maintained at room temperature. Asterisks mark the treatments shown in Figure 2.

| Killing solutions | Time in the solution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitfall | C.A. | E.F. | ||||

| 24h | 48h | 15days | 30days | 15days | 30days | |

| C.A. | yes | yes | yes | yes* | yes | yes* |

| Solution 1 | yes | yes | yes | yes* | yes | yes* |

| Solution 2 | no* | - | - | - | - | - |

| Solution 3 | yes | yes | yes | yes* | yes | yes* |

Electrophoresis of all 24 analyzed individuals. M represents the lambda DNA marker (100 ng/ul) and F represents the control extraction made using fresh tissue. A) Lanes 01 – 06, individuals killed in C.A. (undiluted commercial alcohol), maintained in the killing solution for 48 hours and then transferred to closed vials containing C.A. (01 – 03) and E.F. (03 – 06) and maintained in these storage solutions for 30 days. Lanes 07 – 12, individuals killed in Solution 1 (= E.F.), maintained in the killing solution for 48 hours and transferred to C.A. (07 – 09) and E.F. (10 – 12) and maintained in these storage solutions for 30 days. B) Lanes 13 – 18, individuals killed in the Solution 2 and maintained in this solution for 24 hours. Lanes 19 – 24, individuals killed in Solution 3, maintained in this solution for 48 hours, than transferred to C.A. (19 – 21) and E.F. (22 – 24) and maintained in these solutions for 30 days. All DNA extractions where successful, but those of crickets killed in solution 2 (lanes 13 – 18).

In this study, we investigated the efficiency of ethanol fuel as a pitfall killing solution in terms sampling efficiency, as measured by species richness and accumulated abundance, and in terms of DNA preservation. Our results indicate increased sampling and preservation efficiency of ethanol fuel, compared to the commonly used alternatives. Below we discuss the advantages and disadvantages of using ethanol fuel as a pitfall killing and storage solution, with particular emphasis on large-scale field expeditions.

Financial costsOf the solutions tested in our study, ethanol fuel is the least expensive option: 1 liter of ethanol fuel (US$ 1.25 on average) costs less than half the price of 1 liter of commercial alcohol (US$ 3.15), which does not include the other components, such as glycerin and formaldehyde, which cost around US$ 15.00 a liter (prices for Brazil).

Field logisticsThe transportation of flammable or toxic liquids is dangerous and illegal under Brazilian and international law. This danger increases with the distance, and consequently time spent in transportation. Ethanol fuel presents a partial solution to this limitation: as it can be bought near the field study sites, at any fuel station in Brazil, the distance of transportation is diminished, decreasing the danger. Large field expeditions can use these facilities to reduce the distances of ethanol transportation, thus reducing the risks of accidents, and simplifying expedition logistics. Even so, for transportations and storage of collected material, we recommend using firm, pressure-resistant bottles, with sealed caps, fully filled with ethanol, so as to minimize oxygen within the bottle, reducing explosion risks. We used PET tubes, which have low costs and may be bought in large quantities.

Commercial alcohol has to be purchased in large shops when bought in large quantities, and is hardly available in the small towns that border most of the large conservation areas. Therefore it would require long-distance transportation and represent huge environmental and personal risks. The additional components of the tested killing solutions (glycerin and formaldehyde), are only available in specialized establishments, restricted to a few large cities in Brazil (Brazilian Federal Law n°10.357/2001).

Sampling efficiencyWe showed that ethanol fuel presented higher sampling efficiency, both for species richness and accumulated abundance of ground-dwelling Orthoptera species, therefore maximizing the gains of the sampling effort. We hypothesize that this higher sampling efficiency is related to the lower density and surface tension of the solution 1 (density = 0.81 g/cm3; surface tension = 21.55 mN/m-1) than solution 2 (density = 0.92 g/cm3; surface tension = 48.56 mN/m-1 ) and solution 3 (density = 0.97 g/cm3; surface tension = 55.34 mN/m-1) (

One piece of evidence in favor of our hypothesis is that all winged cricket species captured in this study died exclusively within pitfalls that used ethanol fuel as the killing solution (94 individuals of Eneoptera sp. and 183 individuals of Gryllus sp.). These genera contain species of large body size, which are powerful jumpers as nymphs and powerful fliers as adults, and are rarely captured in conventional pitfall traps killing solution (N. Szinwelski, personal observation). Indeed, C.F. Sperber, in other field collections, has observed adults of Eneoptera sp. flying out of pitfalls with water + detergent killing solution. The alternative pitfall design used to prevent escape from traps, using an inverted funnel at the trap’s top (

To obtain DNA samples, it is recommended that the sampled organisms be removed from the pitfall killing solution as soon as possible and placed in vials containing highly concentrated alcohol, preferably at low temperatures (

Indeed, we were able to obtain sequences of mitochondrial DNA (COI) and nuclear (18S rRNA) of Orthoptera specimens kept for two weeks in ethanol fuel killing solution, before being sorted and stored in undiluted commercial ethanol (92.8°GL), where they remained at 38°C – 45°C room temperature for another 45 days (in Manaus – AM) and 70 days at similar temperature (in Cuiabá – MT).

CounterargumentsOne of the main arguments against the use of ethanol fuel as a pitfall trap killing solution is that it evaporates faster than other solutions, making its use limited to high temperature areas. We were, however, able to use ethanol fuel pitfall traps successfully in Amazon forest sampling (38°C – 45°C), where the traps were kept for 48h in the field without significant volume reduction of the killing solution.

Solution evaporation is a limiting factor in open habitat with high temperatures as Brazilian “Campo Cerrado”, for example. In such field conditions, we recommend increasing the killing solution volume by 100%, from 500ml to 1000ml, to maintain sufficient killing solution volume in the traps after 48h in the field.

Another problem with ethanol fuel is the fact that it can be denatured. In Brazil, that means that every liter of ethanol fuel can contain up to 30ml of gasoline. In the United States every liter of ethanol E85 contain 150ml of gasoline. This may represent an environmental problem if the pitfall is damaged and the solution is spread in the environment. Moreover, gasoline might hinder DNA preservation. For Brazilian ethanol fuel we showed that this did not occur. Even specimens collected in ethanol fuel, were successfully preserved and we were able to extract DNA and run PCR reactions obtaining sequences of mitochondrial COI and nuclear rRNA18S .

We thank I. Brol, L. Szinwelski, S. Oliveira for assistance in the field and N. S. Cardias and I. L. Brol for help in cricket screening. Field facilities were provided by CCZ – Foz do Iguaçu and Iguaçu National Park. This paper is part of Ph.D. theses by N. Szinwelski and M.Sc. theses by V.S. Fialho to be presented to the Postgraduate Program in Entomology at UFV. N. Szinwelski and V.S. Fialho were sponsored by CNPq. This study was supported by research grants by CNPq, CAPES, FAPEMIG and SISBIOTA (CNPq/FAPEMIG – 5653360/2010-0).