(C) 2011 Denis J. Brothers. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

This note is not meant to be an exhaustive account of the many achievements of Alex Rasnitsyn over the 75 years of his life thus far. Apart from anything else, I have little knowledge of his activities outside of my professional interactions with him. Also, there will undoubtedly be several other biographical essays this year to celebrate his accomplishments in many fields. So, my intention, after providing the essential details to place him in context, mainly derived from his personal page on the Paleontological Institute’s website (

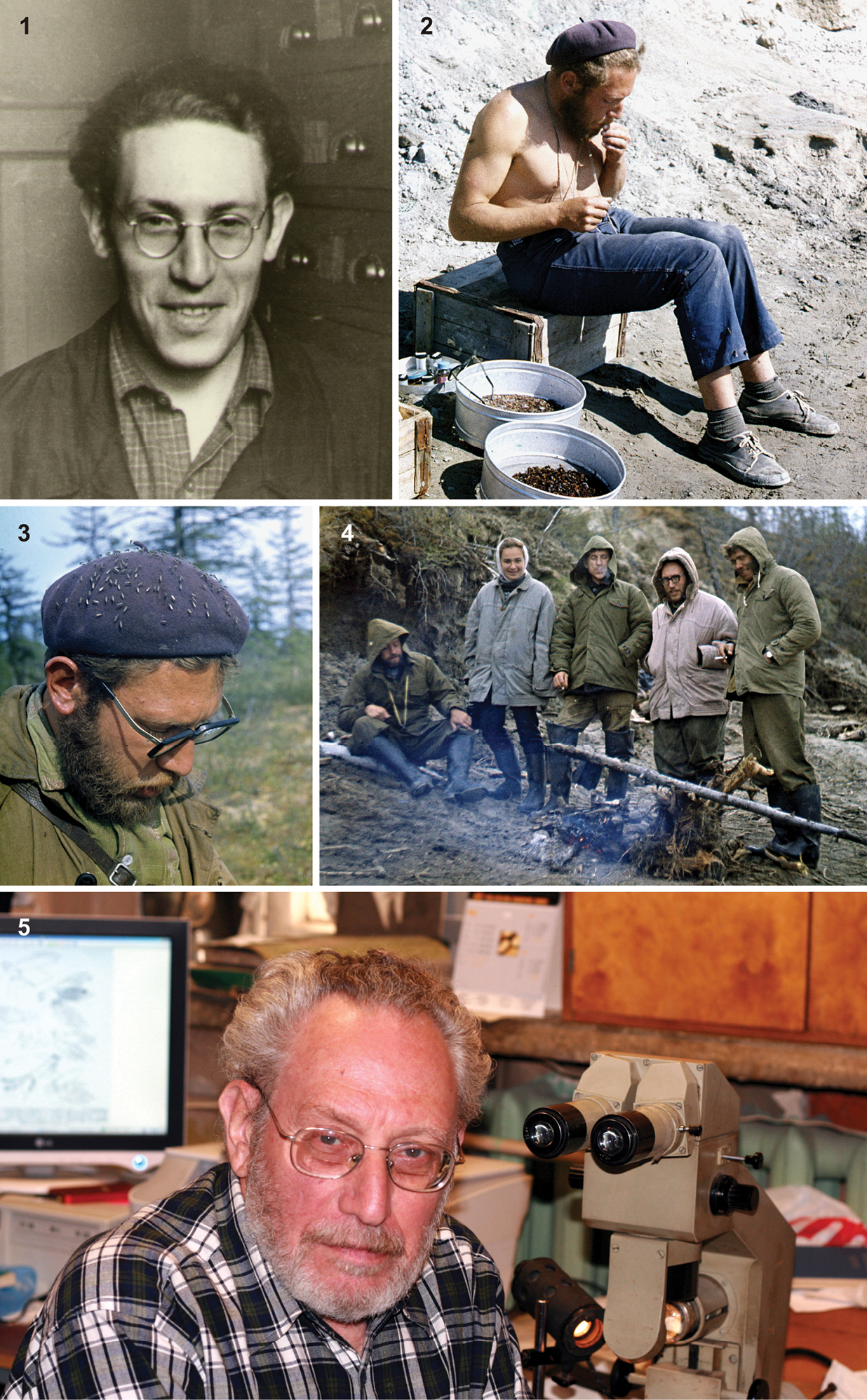

Alexandr Pavlovich Rasnitsyn was born in Moscow, Russia, on 24 September, 1936, and has lived there since. His interest in insects and general natural history soon became apparent, and he joined the Club of Young Biologists at the Moscow Zoo. In 1955 he enrolled at the Moscow State University, and in 1960 graduated with honours and a masters degree in entomology, his thesis being on “Hibernation in the ichneumon flies subfamily Ichneumoninae”, showing that his passion for Hymenoptera was developed right from the start. That same year he joined the Arthropoda Laboratory, headed by Professor Boris Rohdendorf, in the Paleontological Institute of the USSR (now Russian) Academy of Sciences, Moscow. From this start as a young man (Figure 1), he worked his way up sequentially from positions as Technician, Junior and Senior Research Worker, to becoming the Head of the Laboratory (1979–1996), Principal Research Worker (since 1996) and then again Head of the Laboratory (from 2002 after the sudden death of his successor, Vladimir Zherikhin, to the present, Figure 5). He has thus headed the most productive and influential group of palaeoentomologists in the world for 28 years. During his employment he also earned two doctorates from the Paleontological Institute, a PhD in 1967 on “Mesozoic Hymenoptera Symphyta and early evolution of Xyelidae”, and a DSc in 1978 on “Origin and evolution of Hymenoptera”. In 1991 he was awarded the title of Professor, and in 2001 he was given the award of “Honoured Scientist” by the Russian Federation. He served as the first President of the International Palaeoentomological Society (2001–2005), and was given Honorary Membership of the Russian Entomological Society (2004) and has been a member of their Council since 2007. He has long held an honorary appointment at the Natural History Museum, London, England.

By his own account, Alex’s interests encompass not only the palaeontology, phylogeny and taxonomy of Hymenoptera and of insects in general, but also broader biological problems, including evolutionary theory, dynamics of taxonomic diversity, and methodology of phylogenetics, taxonomy, and nomenclature. His fascination with the natural world is unquenchable, as shown by his participation in or leading collecting expeditions over 22 field seasons (starting in 1956) to many famous fossil-insect localities in Central Asia, North Caucasus, Siberia (Figures 2–4), Transbaikalia, Mongolia, England, Germany, USA and Israel. He has also visited collections to study specimens, both fossil and modern, in many countries: Canada, China, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Poland, South Africa, Spain and USA. He has participated in many conferences around the world and in several international research collaborations.

Alex’s incredible productivity and breadth of interests are graphically shown by his publications. The most complete list available to me, a late precursor to

Items authored or co-authored by Alex Rasnitsyn, including abstracts.

| Field of contribution | Year of first item | Year of latest item | Number of items | Items per year | Median year | Modal year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palaeontology of Hymenoptera | 1963 | 2011 | 117 | 2.39 | 2000 | 2000 |

| Palaeontology of other insects | 1974 | 2011 | 111 | 2.92 | 2002 | 2002 |

| Theory of systematics | 1966 | 2010 | 36 | 0.80 | 1992 | 1991 |

| Theory of evolution | 1965 | 2005 | 20 | 0.49 | 1974 | 1971 |

| Modern Hymenoptera | 1959 | 2010 | 17 | 0.33 | 1986 | 1981 |

| Evolution of Hymenoptera | 1965 | 2006 | 15 | 0.36 | 1980 | 1971 |

| Ecology, biodiversity, etc. | 1963 | 1995 | 15 | 0.45 | 1989 | 1989 |

| Miscellaneous topics | 1977 | 2008 | 13 | 0.41 | 2003 | 2004 |

| Evolution of insects | 1976 | 2003 | 11 | 0.39 | 1996 | 1976 |

| Editorial work (books) | 1980 | 2008 | 11 | 0.38 | 1988 | 1985 |

| Total | 1959 | 2011 | 366 | 6.91 | 1997 | 2002 |

Alex Rasnitsyn in Russia, in the laboratories of the Paleontological Institute, Moscow, and in the field. 1 In 1961 (photo by Oleg Amitrov). 2 In 1971, sorting amber at Yantardakh, Maimecha River, Taymyr Peninsula, northern Siberia (71°18'30"N, 99°34'12"E) (photo by Alexandr Ponomarenko). 3 In 1971, with mosquitoes near Yantardakh (photo by Alexandr Ponomarenko). 4 In 1971, at Gubina Gora near Khatanga, Taymyr Peninsula (71°59'54"N, 102°34'22"E); left to right: Alexandr Ponomarenko, Irina Sukacheva, Pol' Perov, Alex Rasnitsyn, Vladimir Zherikhin (photo probably by Anatoly Mikheev). 5 In 2008 (photo by Roman Rakitov).

Obviously, some items would span more than one category, but I have merely assigned each to what I judged to be the single most relevant category. Of the 366, 189 have Alex as sole author, 105 have two authors, 43 have three, 14 have four, 12 have five to nine, and 3 (tributes or obituaries) have more than twenty authors; the average number is 2.1. The frequency of co-authorships has increased over the years, from an average of 1.3 over the first 20 years to 2.6 for the last 20, indicating increasing requests for collaboration from colleagues. The above items include co-authorship with 187 different colleagues, a remarkable spread.

It is no surprise that most of Alex’s contributions have been on Hymenoptera, specially their palaeontology, but also on modern groups and, probably of most general influence, the evolution of the order, the relatively few items in that category building on the others and comprising large and major contributions (specially

I was surprised, however, to discover that Alex’s contributions to the palaeontology of other insect groups, although starting about 15 years after his first contribution on Hymenoptera, have been almost as numerous as those on hymenopteran palaeontology, with the same average number of co-authors (one), and at a higher annual rate over the period of their production. The groups covered range across the entire spectrum of insect orders, including several enigmatic ones whose relationships remain obscure. In all of the other categories his output has been much less and generally earlier in his career, although he has continued to make contributions in all (except for more ecological areas) until recently. Although the bulk of his editorial work was done before about 1991, it included two very significant and influential compilations on insect palaeontology and evolution (

It is obvious from the above that Alex has a fearsome intellect and exhibits boundless dedication and hard work in pursuit of his passion. He is much sought as a collaborator, and he is certainly not slowing down – he produced 19 items in 2010 alone. One might consider that such a person must be self-centred, forceful and entirely focused on his work, but this is not true of Alex. He is a real gentleman, very thoughtful of the needs of others, humble, and ready to participate in non-work-related activities which might expand his appreciation and understanding of the natural world. These are qualities which I have experienced in my many interactions with him.

I first met Alex in 1988 at the XVIII International Congress of Entomology and meeting of the International Society of Hymenopterists, in Vancouver, Canada. We both enjoyed the exchanges with colleagues and chatted about our mutual interests in hymenopteran phylogeny (mine restricted to Aculeata) but prospects for closer collaboration seemed poor, given the political systems in place at the time. At that stage I had no idea that I might become involved in hymenopteran palaeontology myself. The turning point for me came in early 1991 when I was made aware of an extensive collection of Cretaceous insect fossils from the Orapa diamond mine in Botswana, which were housed under the care of Dr Richard Rayner, a palaeobotanist, at the Bernard Price Institute of Palaeontology (BPI), University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. This piqued my curiosity, and I was able to look at several of the blocks containing the most spectacular of the insect fossils. I was immediately struck by a most beautifully preserved specimen of some sort of wasp, which I was able to photograph. On my return home, I fortuitously found the latest issue of the journal Psyche on my desk, and on looking through it discovered that the first paper dealt with Mesozoic Vespidae (

As a consequence, I had even more in common with Alex when we met again later in 1991 at the Second Quadrennial Meeting of the International Society of Hymenopterists in Sheffield, England. We were also both at the Third Quadrennial Meeting of the Society in Davis California, USA in 1995. Then, in 1998, we were both participants in an important symposium and workshop investigating the phylogeny of Hymenoptera, organised by Fredrik Ronquist in Uppsala, Sweden (see

In 1999 I was sent an Eocene fossil wasp wing from Canada for my opinion on its placement, and I immediately referred it to Alex, who identified it as a new genus of primitive sphecid and suggested that it be included in a paper he was currently involved with;

After 1992 I was unable to do any further work on the Orapa material (it being housed 500 km from my home in Pietermaritzburg) for a long time. But I remained painfully aware that there was a treasure trove of Cretaceous material awaiting study in Johannesburg, and could think of no-one better to evaluate its significance than Alex. So I managed to secure funding in 2001 to invite him as a plenary speaker to an entomological conference in Pietermaritzburg and then to spend about three weeks examining the fossils in Johannesburg. During that period I scanned about 2000 rock pieces (containing about 5000 insect fossils) for Hymenoptera and Alex examined the 68 blocks on which I had found at least one hymenopteron, identifying and listing all the fossils and making drawings of the 108 hymenopterons found. I also managed to photograph them. Alex’s experience, persistence and encyclopaedic knowledge permitted us to make an estimate of the insect diversity in the collection (

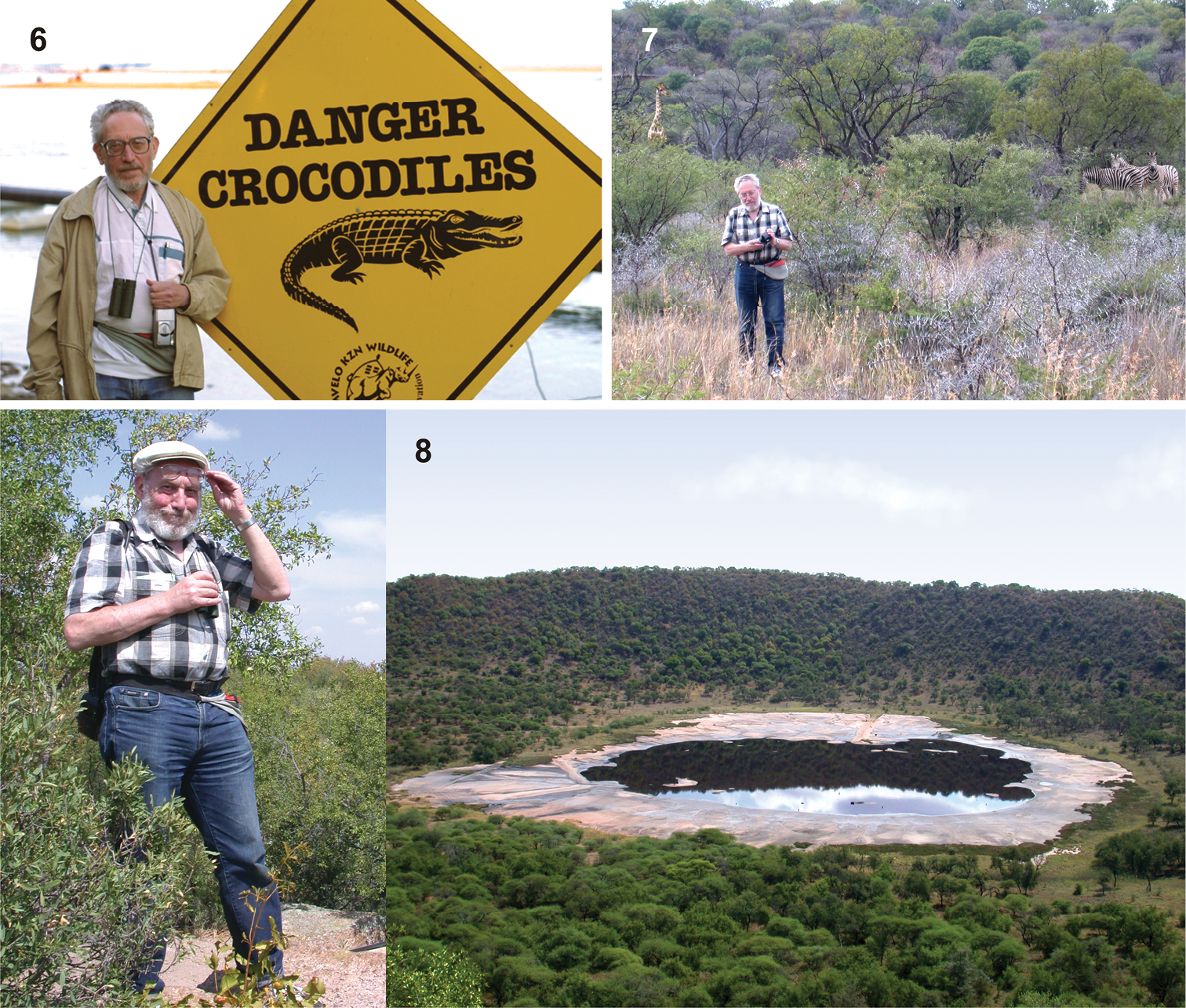

The year 2001 saw further contact, since we both attended the Second International Congress on Palaeoentomology in Krakow, Poland, where Alex was elected the first President of the International Palaeoentomological Society to much acclaim at its founding meeting, and where it was decided that the next such congress would be held in South Africa. This provided another opportunity for him to visit me, and in 2005 he spent some time in Pietermaritzburg, courtesy of funding from the South African government in support of Russian academics visiting our country, before Fossils X 3: 3rd International Congress of Palaeoentomology with 2nd International Meeting on Palaeoarthropodology and 2nd World Congress on Amber and its Inclusions, held in Pretoria. He was also able to do further work on the Molteno Formation (Triassic) fossils amassed by John Anderson at the South African National Botanical Research Institute in Pretoria (a collection now also housed at BPI, Johannesburg). Then Alex came to South Africa again in 2006 for the Sixth International Conference of Hymenopterists, held at Sun City.

I have thus been extremely fortunate to benefit from extensive interactions with Alex, to have him sharing his vast knowledge of Hymenoptera diversity, and patiently explaining palaeontological conventions and practices to someone without any training in palaeontology or even geology. I have always been amazed at his readiness to spend time addressing my concerns and yet obviously being able to spend even more time simultaneously on all his other projects. Nothing has been too much trouble for him. I can only assume that the level of interaction I have had has extended to all of his other collaborators, a very wide diversity of people from all over the world. Obviously, colleagues in all areas of palaeoentomology turn to his advice and participation when faced with interesting problems. To my mind, he embodies the ideal scientist, someone filled with an inexhaustible curiosity about the natural world and its history, able to focus intently on the task at hand and yet able to interrupt that task when necessary and return to it as if the interruption never happened (a skill needed by any manager), and also to enjoy doing something completely different when the opportunity arises. I remember his delight when we travelled from Pietermaritzburg to Johannesburg in 2001 and were able to visit places such as St Lucia (Figure 6) and the Hluhluwe-Mfolozi game reserve where we stayed overnight. He was thrilled by the diversity of game animals and birds, from rhinoceros, elephant and buffalo to oxpeckers and weavers. When we had to leave the reserve he leaned back and said he had been “Alex in Wonderland”. The same enjoyment was in evidence in 2005 when we stayed for a few nights at an eco-estate north of Pretoria (Figure 7) and also when we visited the impact crater about 1 km in diameter and 100 m deep at Tswaing (Figure 8), also north of Pretoria.

Alex Rasnitsyn in South Africa. 6 At the Lake St Lucia estuary mouth, northern KwaZulu-Natal (28°22'58"S 32°25'12"E), July 2001 (photo by Justin Waldman). 7 At Buffelsdrift residential nature reserve, north of Pretoria, Gauteng Province (25°33'41"S 28°20'48"E), February 2005 (onlookers added although also photographed there). 8 Surveying the Tswaing meteorite crater (right), north of Pretoria, Gauteng Province (25°24'38"S 28°05'14"E), February 2005.

The celebration of Alex’s 75th birthday is a wonderful opportunity to look back at his many accomplishments, let him know how much we all appreciate them, and admire his continuing energy and drive in pursuit of his passion. Long may it continue. Happy birthday, Alex, and we certainly wish you many more to come.

I’m grateful for comments by Michael Engel, Mike Sharkey and Dmitry Shcherbakov which enabled me to improve the text. Dmitry also supplied many of the photographs which have contributed significantly to this tribute. The University of KwaZulu-Natal provided financial and infrastructural support.