(C) 2011 Jian-Feng Wang. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

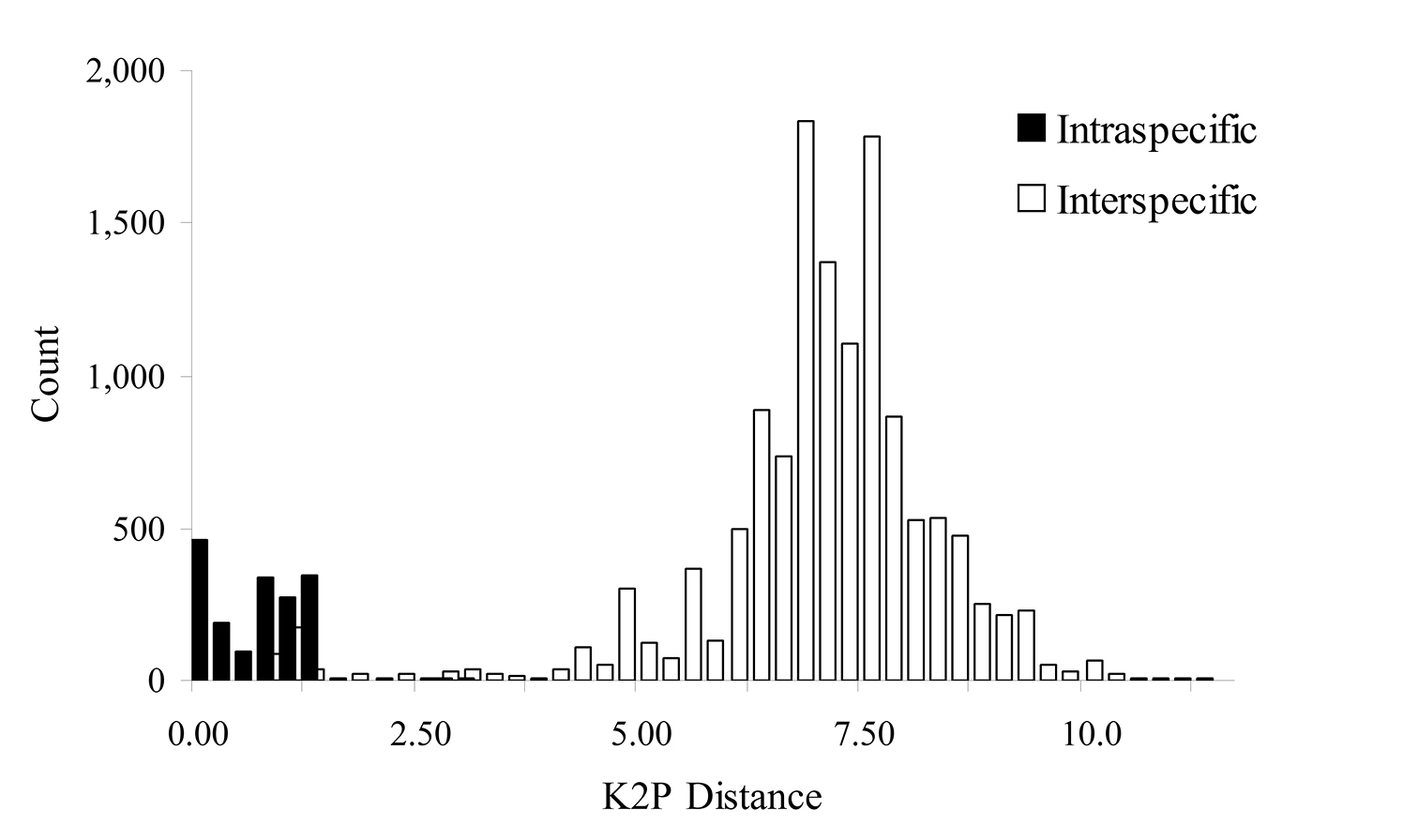

Aphids of the subtribe Aphidina are found mainly in the North Temperate Zone. The relative lack of diagnostic morphological characteristics has hindered the identification of species in this group. However, DNA-based taxonomic methods can clarify species relationships within this group. Sequence variation in a partial segment of the mitochondrial COI gene was highly effective for identifying species within Aphidina. Thirty-six species of Aphidina were identified in a neighbor-joining tree. Mean intraspecific sequence divergence in Aphidina was 0.52%, with a range of 0.00% to 2.95%, and the divergences of most species were less than 1%. Mean interspecific divergence within previously recognized genera or morphologically similar species groups was 6.80%, with a range of 0.68% to 11.40%, with variation mainly in the range of 3.50% to 8.00%. Possible reasons for anomalous levels of mean nucleotide divergence within or between some taxa are discussed.

Hemiptera, Aphidinae, Aphidina, mitochondrial COI gene, intraspecific divergenuce, interspecific divergence, identification

Aphids are globally important invasive agricultural pests (

Resolving species relationships within Aphidina has been hindered by the lack of variation in morphological features. In particular, species of Aphis lack diagnostic morphological characteristics. Although some species can be easily distinguished by a single diagnostic morphological trait, many of them cannot be separated morphologically. Consequently, many species have been grouped according to their gross morphological similarities. The resultant entities, known as “groups of species”, have no taxonomic validity because they simply contain species that are difficult to tell apart morphologically.

Three such “groups of species”, the black-backed, black and frangulae-like groups, have been described in Europe (

Because the identification of aphid species is often

based on presumed host plant specificity, polyphagous or oligophagous

species, such as Aphis craccivora, Aphis fabae and Aphis frangulae/gossypii, can easily be misidentified (

A standard region of the mitochondrial gene that encodes cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) was originally used to identify unknown aphid specimens (

In this paper, we attempt to clarify some of the current taxonomic confusions and previously obscure species relationships within Aphidina. The variation in a short mitochondrial COI gene sequence that we found was used. Its utility was assessed as a method to accurately and quickly identify an assemblage of mainly Chinese aphids at the species level.

Materials and methods Taxon sampling and data collectionWe examined 198 COI sequences; 143 sequences were extracted from Chinese samples, and 55 sequences of European and North American samples were downloaded from GenBank. The ingroup included 176 Aphidina specimens from 36 species (subspecies) (34 species after revision) and 9 genera (subgenera). The outgroup was composed of 22 sequences from 5 species of 2 genera in the sister subtribe Rhopalosiphina (6 sequences), 7 species of 6 genera in Macrosiphini (12 sequences); and 4 species of 4 genera in Fordinae (4 sequences).

Three subgenera of the genus Aphis from the Palaearctic region were represented in our samples, namely Aphis, Bursaphis and Protaphis. Two recognized major “groups of species”, the black-backed and frangulae-like aphids, and some morphologically distinct species (including Aphis spiraecola, Aphis nerii and Aphis farinosa) were also examined.

Collection information for all samples, including locations, host plants and collection dates, are shown in Appendix 1. Except for specimens for slide-mounting that were stored in 70% ethanol, all other specimens were stored in 95% or 100% ethanol. All samples and voucher specimens were deposited in the National Zoological Museum of China, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China.

About 143 samples including many individuals, one to

three individuals per sample were isolated DNA for molecular studies,

and three to five individuals per sample were made to slide-mounted

specimens for morphological examination. Voucher specimens of all

samples were identified from their main morphological diagnostic

features, and compared with previously identified specimens. The

species name of each sample has been provided in Appendix 1. Aphis asclepiadis Fitch was identified from the description of

Total DNA was isolated from one to three individuals

per sample, followed by a standard phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol

(PCI) extraction with some modifications (

Sequencing reactions were performed with the corresponding amplifying primers from both directions using a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit v.2.0 (Applied Biosystems, USA) and run on an ABI 3730 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Assembling and aligning sequencesTo obtain single consensus sequences, chromatograms, including sense and antisense, were analyzed and assembled using the Seqman module of the DNAStar* 5.0 software package (DNASTAR, Inc.1996). We checked the accuracy of the nucleotide sequences by confirming that they could be translated into proteins by using Editseq (DNASTAR, Inc. 1996). Sequences were deposited in GenBank under Accession Nos. FJ965596–FJ965749.

Aphid species’ COI profilesCOI profiles were obtained from a

neighbor-joining (NJ) tree with Kimura-2-parameter (K2P) distances

created using MEGA3.1 (available at http://www.megasoftware.net). The

K2P model provides the best metric when genetic distances are low (

The sequences were manually aligned with the Bioedit sequence editor (

Including outgroups, 52 species were identified among the 198 taxa examined. Of the 591 bp that were analyzed, 373 were conserved, 218 were variable and 191 were parsimony-informative; 404 sites were constant, 187 were variable and 164 were parsimony-informative for ingroups only. These sequences were heavily biased toward A and T nucleotides (means: T = 39.4%, C= 13.9%, A = 34.5%, G = 12.2%).

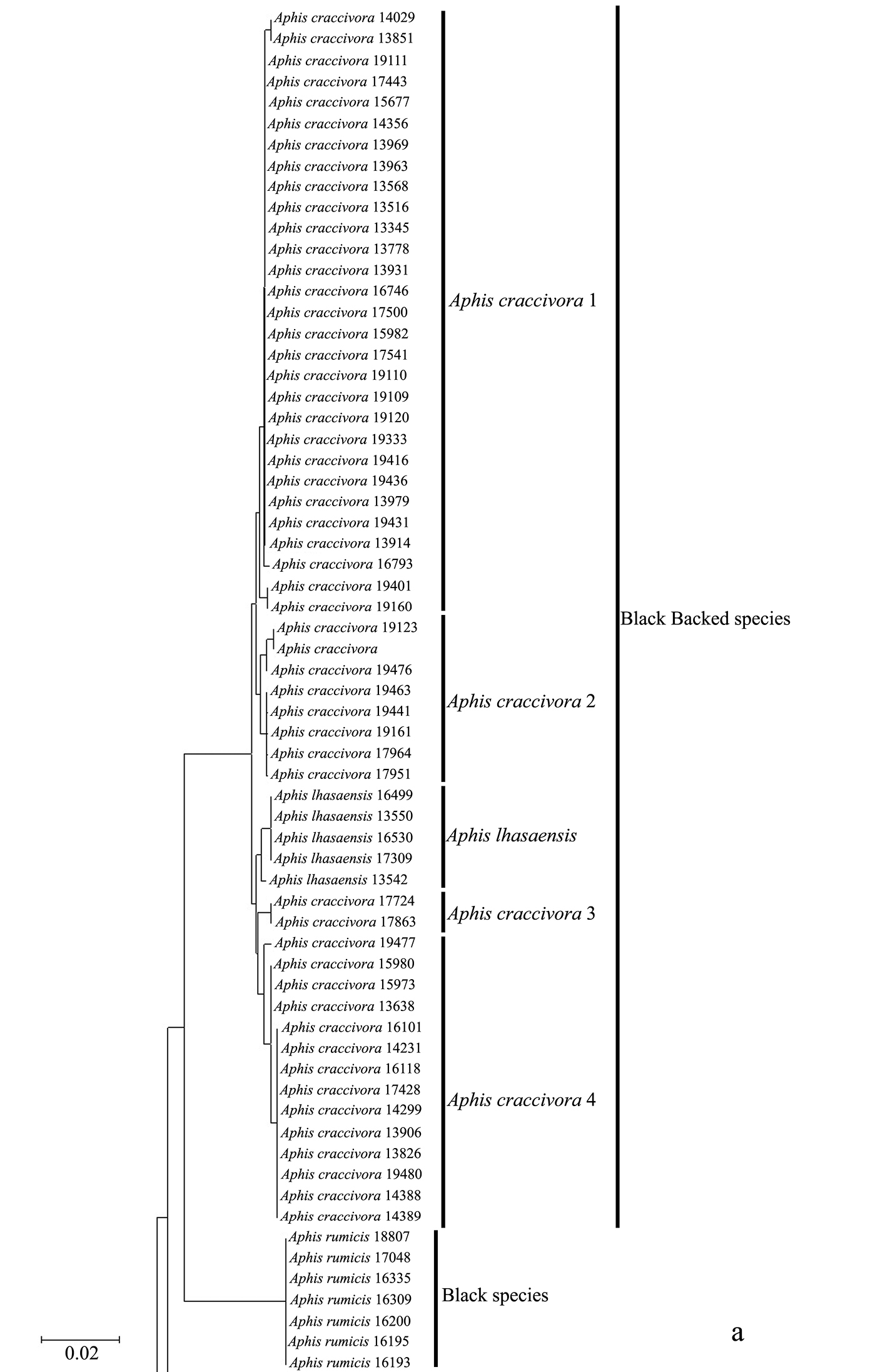

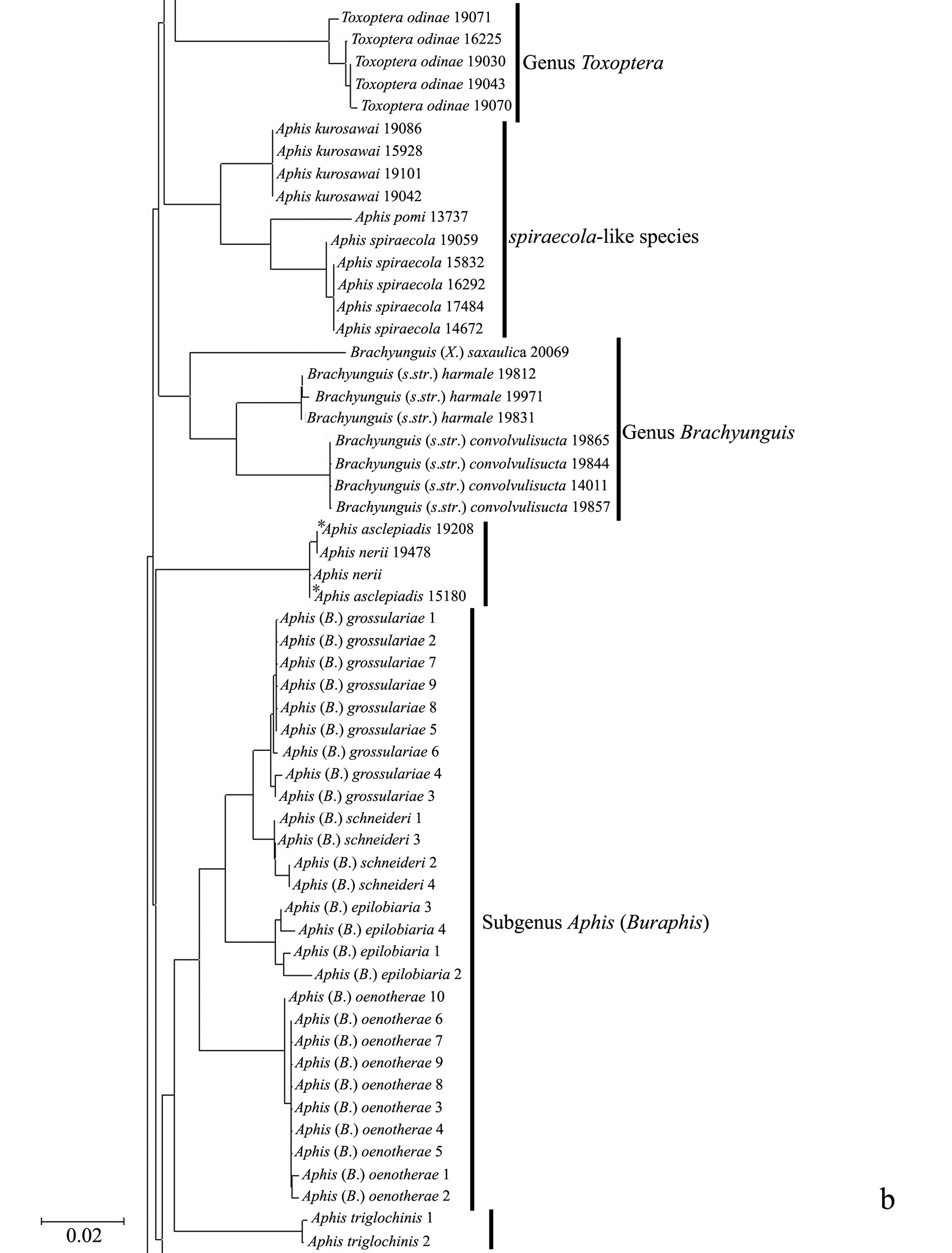

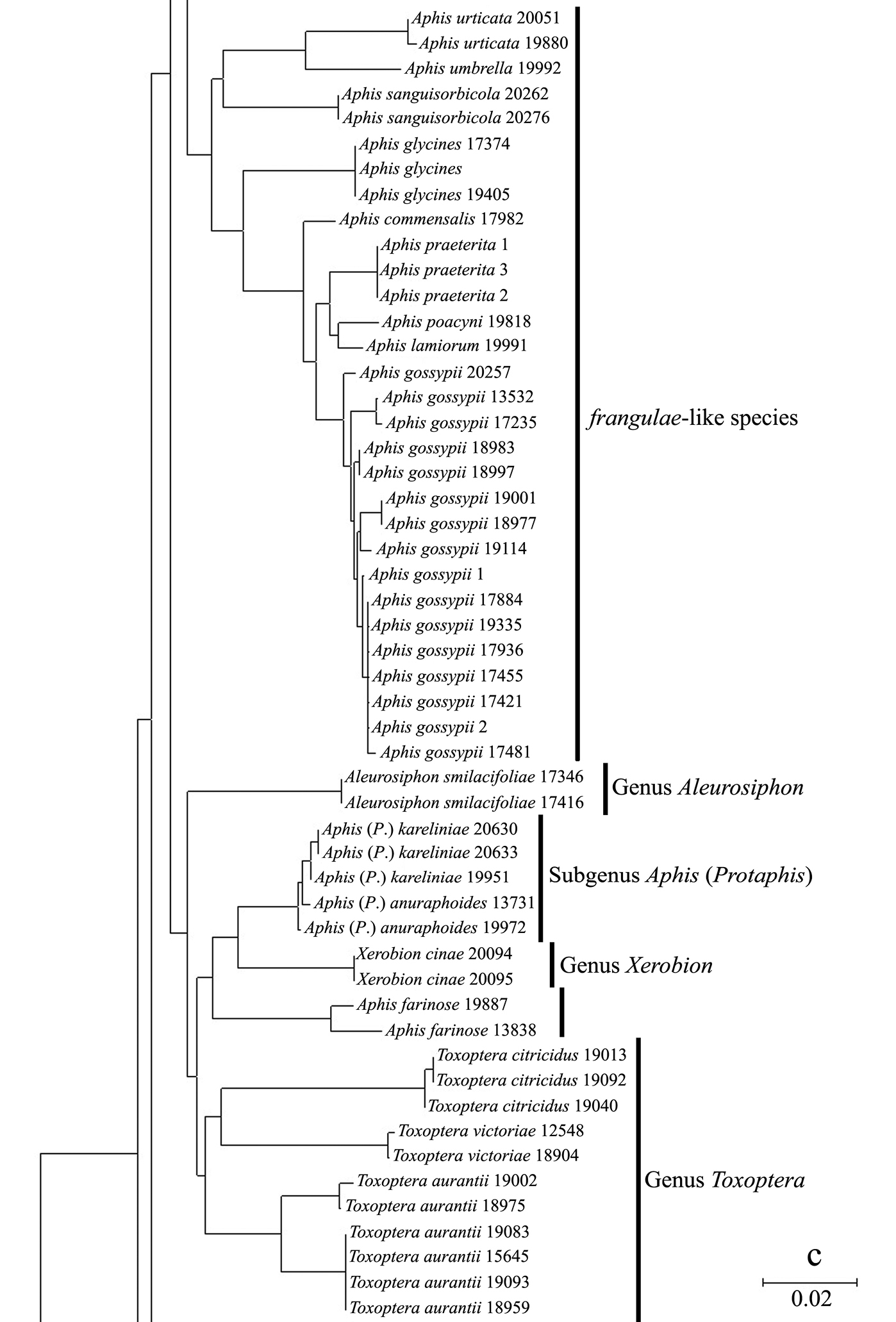

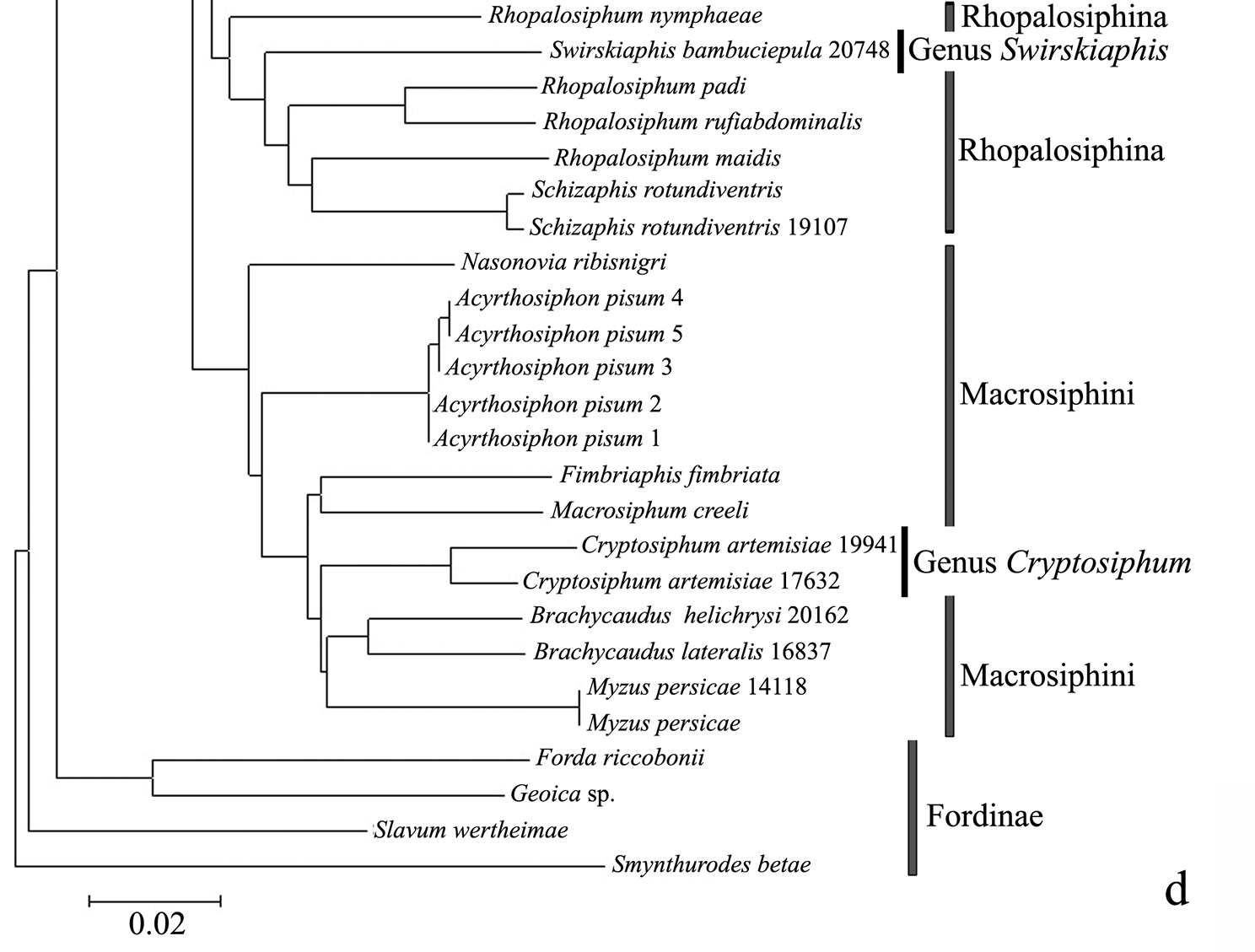

Taxonomic assignments and NJ tree structureIn the NJ tree (Fig. 1a–d), most of the aphid species and subspecies included in our NJ profile possessed a distinct COI sequence. Although the Cryptosiphum artemisiae Buckton clustered with Macrosiphini and Swirskiaphis bambuciepula Zhang was embedded within Rhopalosiphina, all other Aphidina specimens formed a cohesive group. The Rhopalosiphina appear to be a monophyletic sister group to Aphidina, whereas the Macrosiphini and Fordinae are rooted and clustered, separately.

Within Aphidina, two subgenera (Bursaphis and Protaphis) and the three recognized “groups of species” within the subgenus Aphis all formed separate, cohesive clusters. However, the species from the subgenus Aphis did not cluster together but were divided into the following six main clades: ‘black-backed species’, ‘black species’ ‘frangulae-like species’, ‘spiraecola-like species’, Aphis nerii and Aphis farinosa. Aphis nerii and Aphis asclepiadis (=Aphis nerii) cluster together, and with lower nucleotide divergence (0.00%–0.17%).

Neighbor-joining analysis of 198 specimens. It was based on COI sequence divergence in 591 bp of the COI gene using Kimura’s two parameter model.

Neighbor-joining analysis of 198 specimens. It was based on COI sequence divergence in 591 bp of the COI gene using Kimura’s two parameter model. * They were originally misidentified as Aphis asclepiadis Fitch; actually, should be Aphis nerii Boyer de Fonscolombe.

Neighbor-joining analysis of 198 specimens. It was based on COI sequence divergence in 591 bp of the COI gene using Kimura’s two parameter model.

Neighbor-joining analysis of 198 specimens. It was based on COI sequence divergence in 591 bp of the COI gene using Kimura’s two parameter model.

The genus Toxoptera, represented in our sample by sixteen individuals from four species, did not cluster together but was separated into three clades. Although six individuals of Toxoptera aurantii formed a cohesive group, two subgroups were apparent.

Nucleotide diversityAmong 19, 503 pairwise combinations in 198 specimens, the mean COI divergence was 6.99%, with a range of 0.00% to 17.56%, and mostnucleotide divergence ranged from 0.00% to 1.75% and 3.75% to 13.00%.

Omitting Cryptosiphum artemisiae and Swirskiaphis bambuciepula, the mean COI divergence among the 14, 878 species pairs placed within Aphidina by

Histogram of intra- and interspecific nucleotide divergence in Aphidina. Divergences were calculated by using Kimura’s two parameter (K2P) model.

Mean and range of intraspecific nucleotide divergences for Aphidina species. Data were estimated by using Kimura’s two parameter model.

| Species | No. of individuals | Mean percentdivergence % | Range % | SD % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aphis craccivora | 53 | 0.55 | 0.00–1.20 | 0.40 |

| Aphis craccivora 1* | 29 | 0.08 | 0.00–0.51 | 0.13 |

| Aphis craccivora 2* | 6 | 0.26 | 0.00–0.51 | 0.23 |

| Aphis craccivora 3* | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | / |

| Aphis craccivora 4* | 14 | 0.12 | 0.00–0.51 | 0.16 |

| Aphis lhasaensis | 5 | 0.14 | 0.00–0.34 | 0.18 |

| Aphis farinosa | 2 | 1.54 | 1.54 | / |

| Aphis glycines | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Aphis gossypii | 16 | 0.53 | 0.00–1.37 | 0.39 |

| Aphis kurosawai | 4 | 0.11 | 0.00–0.17 | 0.00 |

| Aphis asclepiadis | 2** | 0.17 | 0.17 | / |

| Aphis nerii | 2 | 0.17 | 0.17 | / |

| Aphis praeterita | 3 | 0.20 | 0.00–0.51 | 0.26 |

| Aphis rumicis | 7 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Aphis sanguisorbicola | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | / |

| Aphis spiraecola | 5 | 0.07 | 0.00–0.17 | 0.09 |

| Aphis triglochinis | 2 | 0.17 | 0.17 | / |

| Aphis urticata | 2 | 0.17 | 0.17 | / |

| Aphis (Bursaphis) epilobiaria | 4 | 0.82 | 0.34–1.19 | 0.33 |

| Aphis (Bursaphis) grossulariae | 9 | 0.14 | 0.00–0.51 | 0.14 |

| Aphis (Bursaphis) oenotherae | 10 | 0.10 | 0.00–0.34 | 0.11 |

| Aphis (Bursaphis) schneideri | 4 | 0.23 | 0.00–0.34 | 0.18 |

| Aphis (Protaphis) anuraphoides | 2 | 0.17 | 0.17 | / |

| Aphis (Protaphis) kareliniae | 3 | 0.11 | 0.00–0.17 | 0.10 |

| Aleurosiphon smilacifoliae | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | / |

| Brachyunguis convolvulisucta | 4 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Brachyunguis harmalae | 3 | 0.11 | 0.00–0.17 | 0.10 |

| Cryptosiphum artemisiae | 2 | 2.95 | 2.95 | / |

| Toxoptera aurantii | 6 | 1.50 | 0.00–2.95 | 1.41 |

| Toxoptera citricidus | 3 | 0.11 | 0.00–0.17 | 0.10 |

| Toxoptera odinae | 5 | 0.37 | 0.00–0.85 | 0.29 |

| Toxoptera victoriae | 2 | 0.17 | 0.17 | / |

| Xerobion cinae | 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | / |

| All | 169 | 0.52 | 0.00–2.95 | 0.44 |

*intraspecific clades.** The two samples were originally misidentified as Aphis asclepiadis Fitch; actually, they should be Aphis nerii Boyer de Fonscolombe.

Interspecific nucleotide divergences for species in 9 genera or “groups of species” in Aphidina. Data were estimated by using Kimura’s two parameter model.

| Groups | No. of species (individuals ) | Mean percentdivergence % | Range % | SD % |

| Black backed species | 5* (58) | 0.83 | 0.51–1.20 | 0.18 |

| Black backed species | 2 (58) | 0.80 | 0.68–1.20 | 0.09 |

| spiraecola-like species | 3 (10) | 3.85 | 3.31–4.55 | 0.32 |

| frangulae-like species | 9 (30) | 4.90 | 1.20–8.91 | 2.16 |

| Aphis (Protaphis) | 2(5) | 0.54 | 0.34–0.68 | 0.13 |

| Aphis (Buraphis) | 4 (27) | 3.40 | 0.85–4.41 | 1.05 |

| Brachyunguis | 3 (8) | 5.01 | 3.84–6.97 | 1.49 |

| Toxoptera | 4 (11) | 6.83 | 2.59 | 2.11 |

| All (revised) | 32* (173) | 6.80 | 0.68–11.4 | 1.45 |

* No. of clades.

As expected from previous DNA studies of aphids (

The magnitude of COI divergence varies among different animal groups.

This degree of intraspecific divergence is similar to

that found in other animal taxa. For example, treating the provisional

species as separate taxa, the 0.52% intraspecific variation we found

in Aphidina is comparable to values reported for other taxa, such as 0.27% in North American birds (

The six specimens assigned to the species Toxoptera aurantii

(Boyer de Fonscolombe) were divided into two different clades, with

divergences ranging from 2.59% to 2.95%, far higher than those between

the other Aphidina species. This result indicated that Toxoptera aurantii

probably contains cryptic species, but we did not find any distinct

morphological differences after checking the specimens. These results

were consistent with the conclusions of

Omitting Cryptosiphum artemisiae, which should be moved into the tribe Macrosiphini (

However, mean divergences among the black-backed “groups of species” and the two species of Aphis (Protaphis) ranged from 0.34% to 0.85%, far lower than that between the other Aphidina groups, and the divergence between Aphis (Bursaphis) grossulariae Kaltenbach and Aphis (Bursaphis) schneideri (Börner) was also unusually low (0.85%).

Systematic status of some taxaPairwise COI sequence divergence among congeneric animal species is generally over 2% (

Evidence for host races within Aphis craccivora

In our NJ tree, Aphis craccivora was divided into four clades and clustered together with Aphis lhasaensis Zhang. Pairs of clades in this group had COI sequence divergences ranging from 0.51% to 1.20% (mean=0.83%), lower than the interspecific divergences of the other aphids. Aphis lhasaensis was found in Tibet, infesting subterranean parts of Astragalus sinicus L. (Fabaceae). It is similar to Aphis craccivora, except that its abdominal segments II–IV have large marginal tubercles. Our results suggest that Aphis lhasaensis should be regarded as a Tibetan subspecies of Aphis craccivora rather than a separate species. Two of the four clades of Aphis craccivora showed some evidence of association with different host plants in the same family Fabaceae, indicating the presence of host-adapted races in Chinese populations of this species. In particular, 13 out of 14 samples collected from Robinia pseudocacia were of clade 1, and 12 out of 22 samples of Sophora japonica were of clade 4.

The Chinese record of Aphis asclepiadis Fitch should be referred to Aphis nerii Boyer de Fonscolombe

Swirskiaphis bambuciepula Zhang and Zhang should be in Rhopalosiphina

Swirskiaphis was erected by

Mean intraspecific sequence divergence in Aphidina was 0.52%, with a range of 0.00% to 2.95%, and the divergences of most species were less than 1%. The mean interspecific divergence with Aphidina was 6.80%, with a range of 0.68% to 11.40%, and most genera were in the range of 3.50% to 8.00%. A short COI sequence proved to be very useful for the identification of species within Aphidina. However, more specimens and DNA sequences are required to solve the remaining problems in classification and phylogeny.

We grateful thank to anonymous reviewers and subject editor, M Wilson for their valuable suggestions and comments to make this ms a good contribution, and are indebted to CP LIU of the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences for making slides. The work was supported by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (Grant No. 30830017, 30970391), National Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists (No. 31025024), National Science Fund for Fostering Talents in Basic Research (No. J0930004), a grant (No. O529YX5105) from the Key Laboratory of the Zoological Systematics and Evolution of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (MOST GRANT No. 2006FY110500).