(C) 2012 Susumu Ohtsuka. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

A new species of the endoparasitic copepod Enterognathus (Cyclopoida, Enterognathidae) is described from a crinoid host in the Seto Inland Sea, western Japan. This is a third species of the genus and its first occurrence in the Pacific Ocean. The new species is distinguished from two previously known congeners by the morphology of the body somites, caudal rami, antennae and legs. Crinoid parasites belonging to Enterognathus and the closely related genus Parenterognathus have a broad distribution from the northeastern Atlantic through the Red Sea to the West Pacific.

Copepoda, Cyclopoida, Enterognathidae, Seto Inland Sea, symbiosis

The cyclopoid copepod family Enterognathidae is a compact group accommodating only four genera and six species (

During a research cruise in the Seto Inland Sea, western Japan in 2011, we found an undescribed species of the genus Enterognathus in a benthic sample. The genus has hitherto consisted of only two species, Enterognathus comatulae Giesbrecht, 1900 from the northeastern Atlantic and Enterognathus lateripes Stock, 1966 from the Red Sea (

A juvenile of the crinoid genus Lamprometra sp. (cf.

Terminology follows

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:E102BE09-F9D6-42CF-8C1F-5AA04090276D

http://species-id.net/wiki/Enterognathus_inabai

Figs 1 –2An adult female found from the crinoid Lamprometra sp. collected from the central part of the Seto Inland Sea, western Japan (34°0.590'N, 132°44.32'E–34°0.599'N, 132°44.35'E), at depths of 46.7–46.9 m, November 7, 2011.

♀, partly dissected, with appendages on 5 slides and body in a vial (KMNH IvR 500, 539).

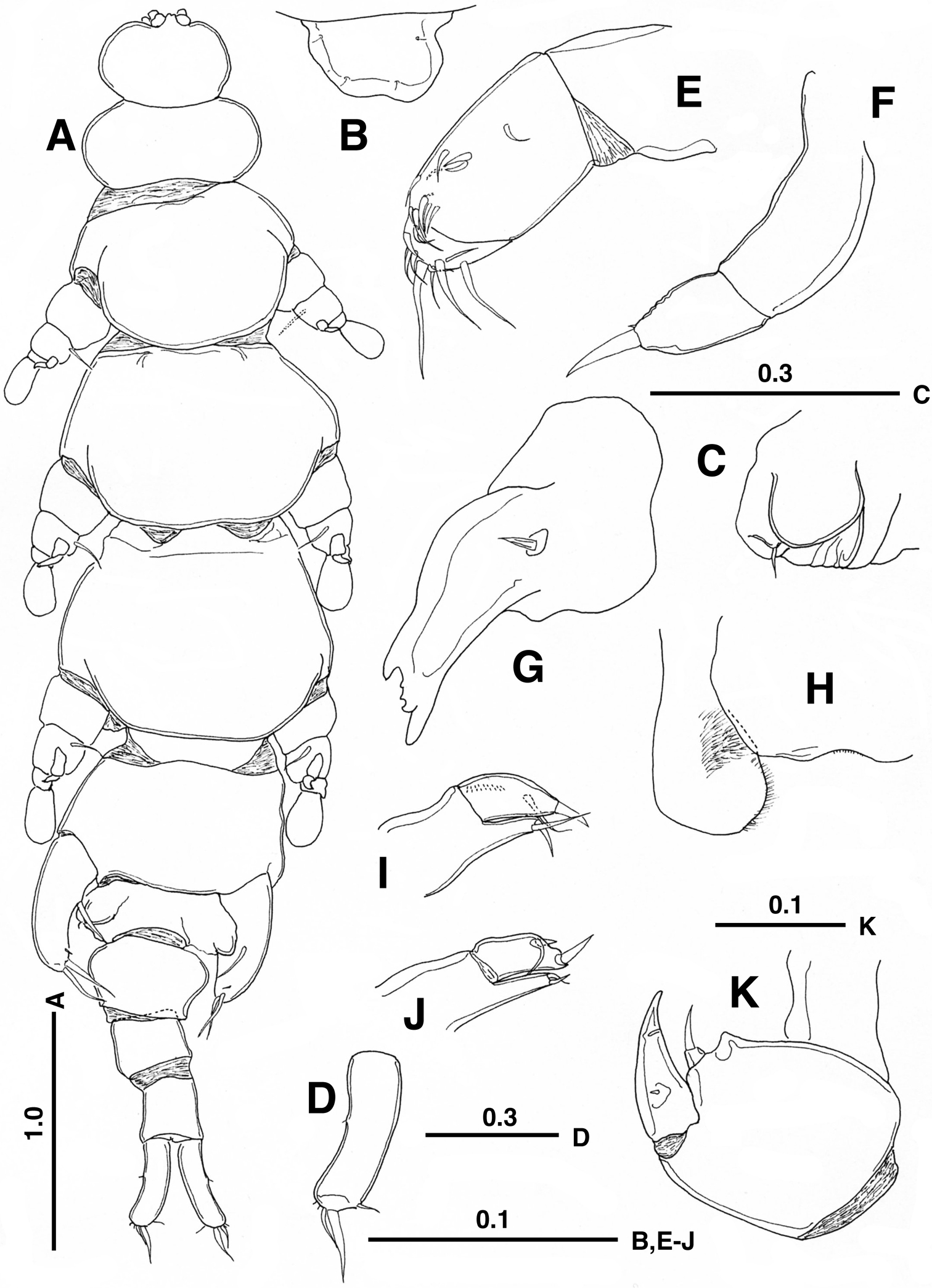

Female. Body (Fig. 1A) 5.17 mm long, from anterior tip of rostrum to caudal ramus excluding caudal setae, flattened dorso-ventrally, weakly sclerotized, elongate, but tagmosis clearly defined. Cephalosome ca. 1.2 times wider than long; rostrum (Fig. 1B) defined basally, slightly asymmetrical with 2 pairs of hair-sensilla. First to fifth pedigerous somites about 2.5, 1.6, 1.6, 1.2 and 1.7 times wider than long, respectively; fourth pedigerous somite (slightly twisted toward right side in Fig. 1A) exhibiting maximum width; genital double-somite protruded laterally into triangular process; each genital opening (Fig. 1C) covered with operculum representing leg 6 and armed with minute seta; single copulatory pore possibly located on posteroventral surface as in Enterognathus comatulae (see Fig. 4 in

Enterognathus inabai sp. n. holotype female: A Habitus, dorsal view B Rostrum, dorsal view C Genital opening, right, dorsal view D Caudal ramus, left, dorsal view E Antennule F Antenna G Mandible H Labrum and paragnath, ventral view I Maxillule J Other maxillule K Maxilla. Scales in mm.

Antennule (Fig. 1E) short, 3-segmented; first segment unarmed; second segment longest, with 10 short setae; third segment with 11 setae. Antenna (Fig. 1F) short, 2-segmented; basal segment long, unarmed; distal segment short, with 1 short seta and 1 rudimentary seta at tip. Mandible (Fig. 1G) with heavily sclerotized gnathobase; cutting edge with large and dorsal and ventral teeth and 2 smaller teeth; palp represented by simple seta. Labrum (Fig. 1H) with concave posterior margin. Paragnath (Fig. 1H) large, expanded distally, hirsute along inner margin. Maxillule (Fig. 1I) 2-segmented; proximal segment bearing praecoxal endite armed with 1 spiniform element and short seta distally; distal segment with 1 subterminal seta, 1 distal spine and row of spinules; other member of pair (Fig. 1J) abnormal, bilobed, with 2 spiniform elements and seta. Maxillae (Fig. 1K) connected by intercoxal sclerite; syncoxa with triangular process and single endite furnished with distal seta; basis with stout spine terminally; endopod represented by rudimentary seta. Maxilliped absent.

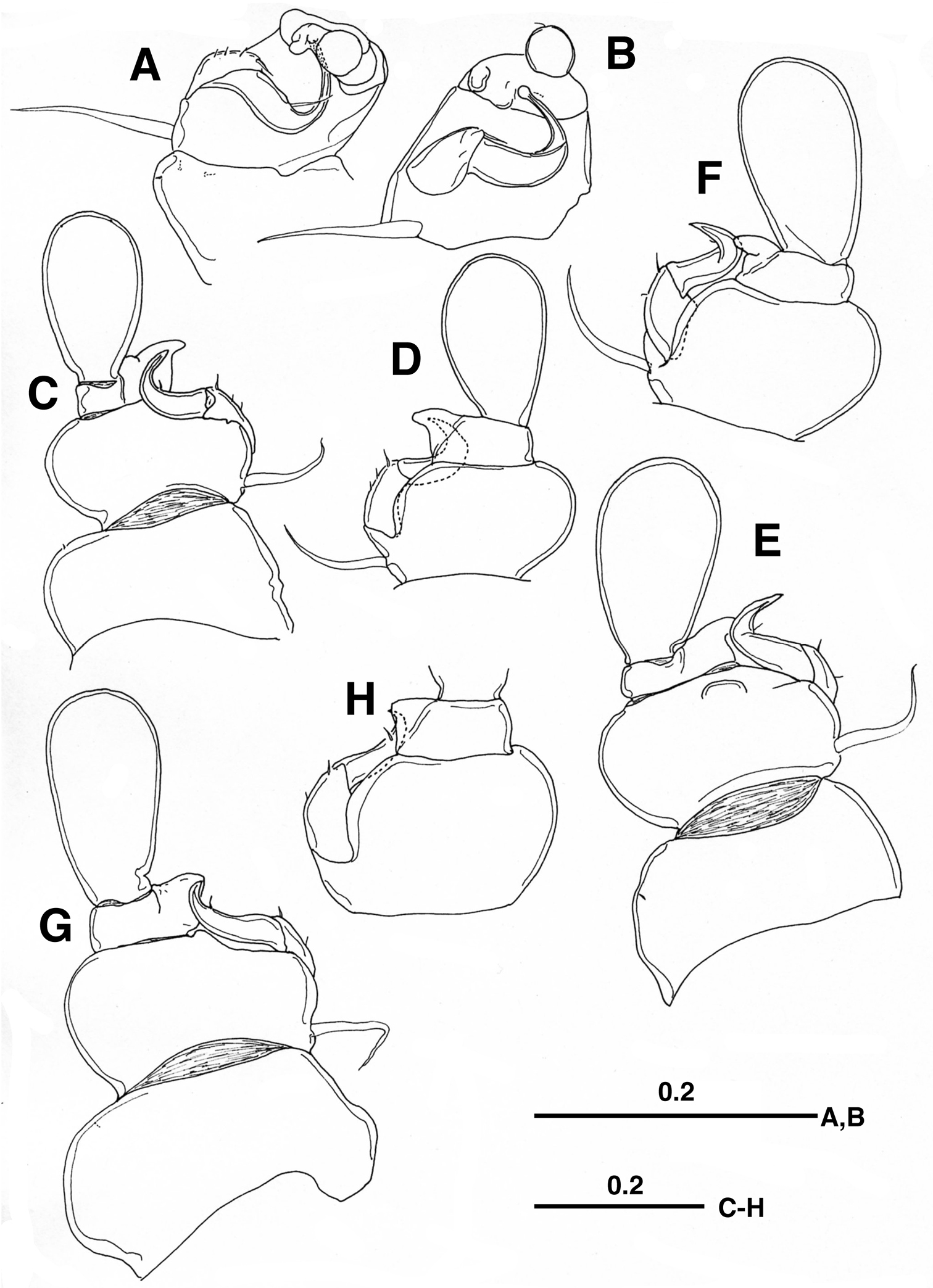

Legs 1–4 biramous, with 2-segmented rami. Legs 1 and 2–4 ventrally and ventrolaterally positioned on pediger, respectively. Leg 1 (Fig. 2A, B) with minute outer setule on coxa; basis furnished with developed naked outer seta basally; first exopodal segment with 3 setules and longer distal setal element on outer margin, second segment sickle-shaped, abruptly curved outward, terminated at round tip, with naked seta at outer midlength; first endopodal segment broad, with 2 rounded projections, second segment bulbous, with minute seta terminally. Legs 2–4 (Fig. 2C–H) similar to each other, but gradually increasing in size; first exopodal segment bearing 3 or 2 setules/setal elements in legs 2 and 3–4, respectively; second exopodal segment curved outward, sharply pointed, with minute setule midway or subterminally; first endopodal segment produced outward into triangular process; second endopodal segment spatulate, unarmed.

Leg 5 (Fig. 1A) 1-segmented, with 1 basal and 2 terminal, developed setae and 1 minute seta subterminally. Leg 6 (Fig. 1C) represented by genital operculum bearing minute seta.

Male unknown.

The new specific name “inabai” is named in honor of the late emeritus Professor Akihiko Inaba (Hiroshima University) who made great contributions to the faunistic surveys of the Seto Inland Sea (

The present new species is more closely related to Enterognathus lateripes from the Red Sea than to Enterognathus comatulae from the northeastern Atlantic in sharing synapomorphies such as reductions in segmentation and setation: (1) only one developed seta on the caudal ramus (2 developed setae in Enterognathus comatulae); (2) 2-segmented antenna lacking a basal seta (3-segmented, with a single seta on the first segment); (3) a single element on the maxillary basis (2 elements); (4) fewer elements on the distal endopodal and exopodal segments of leg 1 (more elements); (5) 3 developed setae on the fifth leg (4 developed setae).

However it is readily distinguished from Enterognathus lateripes in the following features: (1) pedigers 2–5 wider than long (longer than wide in the latter); (2) the first post-genital somite much wider than long (about as long as wide); (3) the second and third post-genital somites about as long as wide (longer than wide); (4) the caudal ramus with 6 setae (4 setae); (5) the terminal seta of the antenna shorter than the second segment (longer); (6) the fifth leg armed with 3 developed setae and 1 minute setule (3 developed setae only); (7) the shape of the distal endopodal segments of legs 1 and 2–4 bulbous and spatulate, respectively (more or less irregular-shaped).

Members of the Enterognathidae have been characterized by the possession of a maximum of 4 setae on the female caudal ramus (see

Enterognathus inabai sp. n. holotype female: A Leg 1, posterior view B Leg 1 excluding coxa (more or less flattened), posterior view C Leg 2, posterior view D Leg 2 excluding coxa, anterior view E Leg 3, posterior view F Leg 3 excluding coxa, anterior view G Leg 4, posterior view H Leg 4 excluding coxa and second endopodal segment, anterior view. Scales in mm.

Key to species of Enterognathus (females only)

| 1 | Two well developed setae on the caudal ramus; antenna 3-segmented with a single seta on first segment; 4 developed setae on fifth leg; body length <5 mm (3.8–4.5mm) | Enterognathus comatulae Giesbrecht, 1900 |

| – | Only a single well developed seta on the caudal ramus; antenna 2-segmented without a basal seta; 3 developed setae on fifth leg; body length >5 mm | 2 |

| 2 | Pedigers 2–5 wider than long; first post-genital somite much wider than long; second and third free abdominal somites about as long as wide; fifth leg armed with 3 developed setae and 1 minute setule; body length ca. 5.2 mm | Enterognathus inabai sp. n. |

| – | Pedigers 2–5 longer than wide; first post-genital somite as long as wide; second and third free abdominal somites longer than wide; fifth leg furnished with 3 developed setae only; body length ca. 6.1–6.3 mm | Enterognathus lateripes Stock, 1966 |

We express our sincere thanks to Professor Geoffrey A. Boxshall for his critical reading of the early draft. Thanks are due to the captain and crew of T/RV Toyoshio-maru, Hiroshima University for their cooperation at sea. The present study was in part supported by grants-in-aid from the Japan Society of the Promotion of Science awarded to SO (No. 20380110) and from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture to MS (No. 21770100).