(C) 2012 Aline Ferreira Quadros. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Many arthropods, including terrestrial isopods, are capable of entering a state of tonic immobility upon a mechanical disturbance. Here we compare the responses to mechanical stimulation in three terrestrial isopods Balloniscus glaber, Balloniscus sellowii and Porcellio dilatatus. We applied three stimuli in a random order and recorded whether each individual was responsive (i.e. showed tonic immobility) or not and the duration of the response. In another trial we related the time needed to elicit tonic immobility and the duration of response of each individual. Balloniscus sellowii was the least responsive species and Porcellio dilatatus was the most, with 23% and 89% of the tested individuals, respectively, being responsive. Smaller Balloniscus sellowii were more responsive than larger individuals. Porcellio dilatatus responded more promptly than the Balloniscus spp. but it showed the shortest response. Neither sex, size nor the type of stimulus explained the variability found in the duration of tonic immobility. These results reveal a large variability in tonic immobility behavior, even between closely related species, which seems to reflect a species-specific response to predators with different foraging modes.

Death-feigning, anti-predator strategies, Crinocheta

To be successful in avoiding their predators, preys engage in a multitude of behaviors, such as the construction of shelters (

Tonic immobility is a state of reversible physical immobility and muscle hypertonicity, during which the organism lack responsiveness to external stimulation (

Amongst crustaceans, tonic immobility has been observed in crabs and terrestrial amphipods and isopods. Terrestrial isopods (Oniscidea) are preyed upon by a large variety of animals: spiders (

The conglobation ability of “rollers” and “spiny forms” is, for sure, a well-known example of tonic immobility in response to disturbance. As pointed by

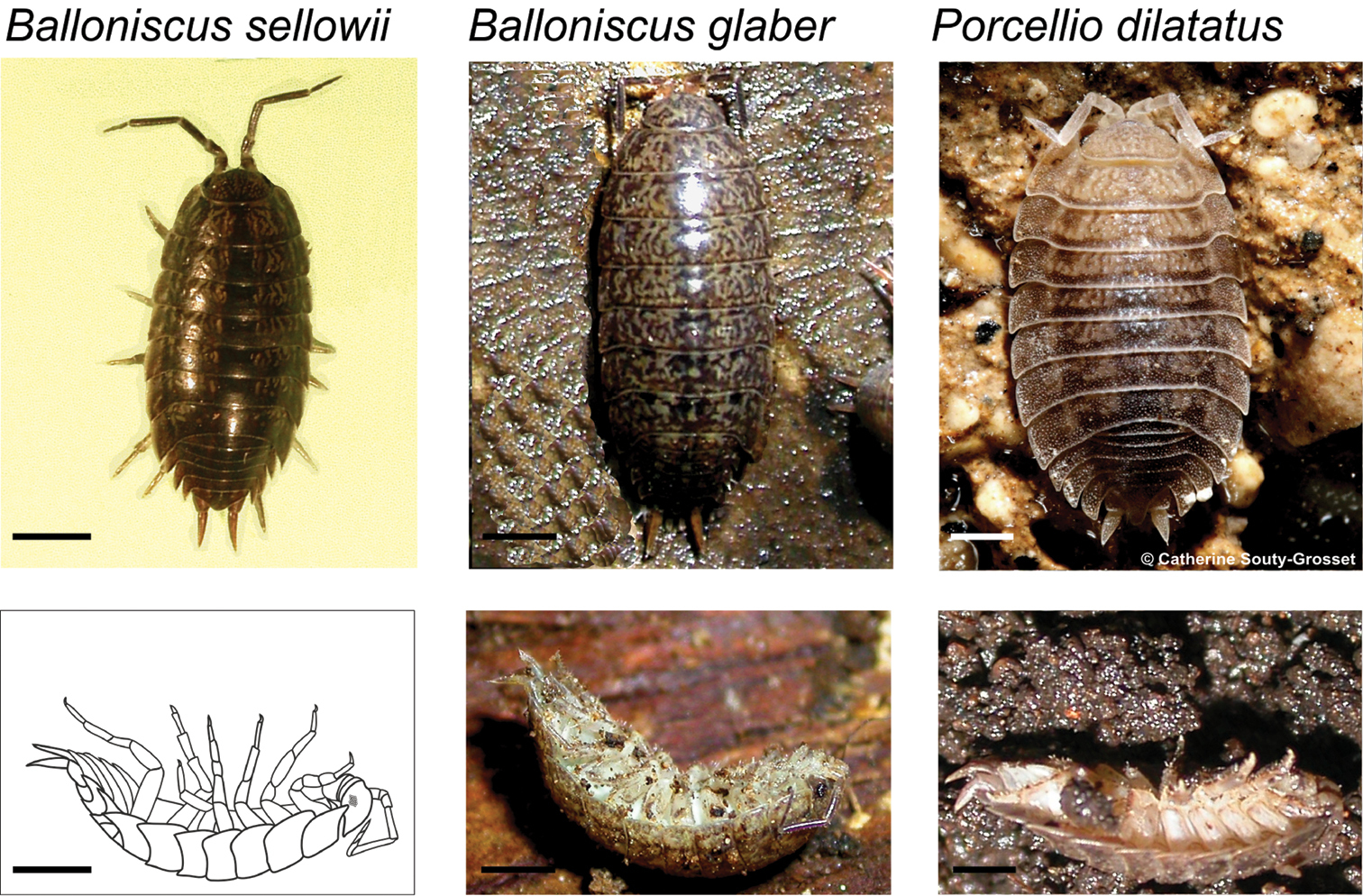

Leaf litter samples containing Balloniscus glaber, Balloniscus sellowii and Porcellio dilatatus (Fig. 1) were collected in urban areas and vicinities of the campus of Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, in Porto Alegre, in the south of Brazil. Balloniscus glaber were captured in July 2008, and Balloniscus sellowii and Porcellio scaber, in July and November 2009, respectively.

Terrestrial isopods studied in dorsal view: Balloniscus sellowii, Balloniscus glaber (Balloniscidae) and Porcellio dilatatus (Porcellionidae) (top) and their respective postures during tonic immobility (bottom). For Balloniscus sellowii a drawing made from a photograph is presented. Bars = 2 mm.

In the laboratory, we randomly pick 60 intermoult individuals (near 1:1 sex ratio) of each species and put them individually in Petri dishes (9 cm diameter)containing moist soil, food (decayed leaves) and plastic black shelters. They were left undisturbed for 72 h prior to the trials. Ovigerous females or females with an empty marsupium were not used in the trials. The isopods were maintained side by side in a large shelve, about 1.30 m height, illuminated by phosphorescent light, in a room with temperature of 20°C and a 12:12 photoperiod. To minimize manipulation prior the trials, the individuals were measured (cephalothorax width) only at the end of the experiments.

Types of stimuliWe choose three different stimuli to be applied to the isopods: touch, squeeze and drop. These stimuli are known to elicit tonic immobility as they frequently did so when we are handling isopods of various species in the laboratory, and they could mimic the mode of action of different predators. The stimulus “touch” consisted of repeatedly pinching the isopod’s body laterally with the tip of a metal forceps and gently pushing it. When inspecting soil and litter samples, it is very common to observe tonic immobility in the isopods after touching/pushing then (pers. obs.). The stimulus “squeeze” consisted of grabbing the isopod with a forceps and slightly squeezing it, in an attempt to simulate the bite of an ant. The “drop” stimulus consisted of grabbing the isopod with a forceps, lifting it approx. 10 cm and then letting it drop in the dish. Here we were trying to mimic a larger predator, such as a small bird or lizard, letting the isopod to fall after grabbing it. The experiments that will be described below were conducted always by two observers, and the observer that applied the stimuli to the isopods was the same throughout all the trials. Care was taken to apply the stimuli and not causing injuries to the isopods. In fact, seven Porcellio dilatatus and one Balloniscus sellowii died during the acclimation period but there was no mortality during the experiments.

Experiment 1To answer questions 1, 2 and 3 we applied the three different stimuli described above to each individual in a random sequence. Each species was tested on a separate day, and all individuals of the same species were tested on the same day. Before starting the trials, the shelters and leaves were removed from all petri dishes to allow a proper observation of isopod behavior.

We started the trial by randomly picking a number corresponding to an individual and a number corresponding to a stimulus to be applied to that individual (e.g. 1 for touch, 2 for squeeze, 3 for drop). Then, we removed the lid of the petri dish and applied the stimulus to the isopod. The stimulus was repeated up to 3× in case of “squeeze” or “drop” or 5× in case of “touch”. If the stimulus did not elicited tonic immobility, the individual was considered non-responsive. If the individual responded, i.e. showed the characteristic posture of tonic immobility (see Fig. 1), the duration of tonic immobility was recorded with a stopwatch. The end of the response was when the individual showed any slight movement, which usually began with a movement of the antenna. The lid was placed again on the dish and another number was randomly picked. These procedures were repeated until all individuals have been subject to the three stimuli.

Experiment 2To answer question 4 we conducted a second experiment, on the day after experiment 1, with the same individuals. The order of the individual was defined randomly as in the experiment 1. We removed the lid of the dish and stressed the isopod with the tip of a forceps for up to 30 seconds, i.e. applying only the “touch” stimulus. If during this period the stimulus did not elicit tonic immobility, the individual was considered non-responsive. If the isopod responded, it was recorded both the time it took to respond (to enter the posture) and the duration of response.

AnalysesProportion data from experiment 1 was compared with a G test of independence (for two samples) or a chi-square test (one sample). The relationship between individual size and its responsiveness was investigated with a logistic regression. To answer question 3, the differences in the duration of tonic immobility among species and stimuli was tested with ANOVA and Tukey test. Also for each species the relationship between duration and size was tested with ANCOVA using sex as the co-variable. Finally, to answer question 4, a linear regression was applied to verify if there was relationship between the time to elicit tonic immobility and duration of response (experiment 2). For all tests the duration of response was log-transformed. All tests were made using the R© Software v. 2.13.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2011).

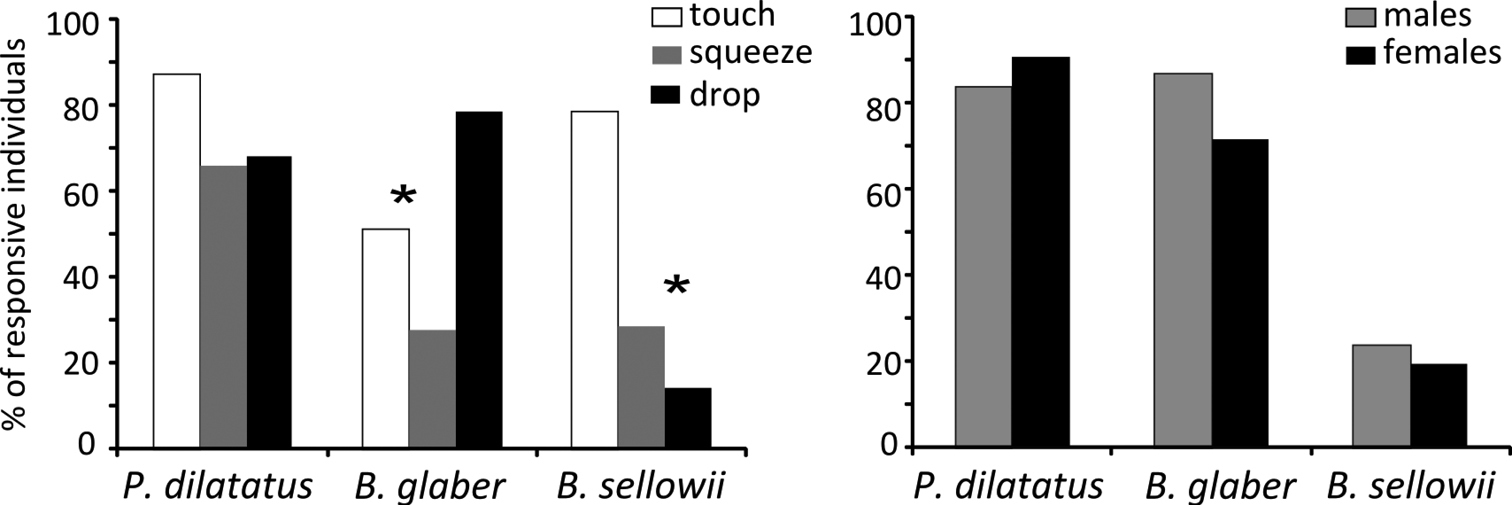

Results Experiment 1 Do the species differ in responsiveness?Porcellio dilatatus and Balloniscus glaber differed remarkably from Balloniscus sellowii (G=62.26; p<0.0001) (Fig. 2A): Porcellio dilatatus and Balloniscus glaber were the most responsive species and did not differ from each other; 89% and 78% of their individuals, respectively, were responsive to at least one of the stimuli applied; 51% of the responsive Porcellio dilatatus individuals were responsive to all three stimuli applied, while only 12% of Balloniscus glaber individuals’ were so. Balloniscus sellowii differed from both species in that only 23% of the tested individuals were responsive to at least one stimulus and none responded to all three stimuli (Fig. 2A).

Responsiveness and tonic immobility duration in terrestrial isopods. A Percentage of responsive individuals in the three species tested. The * indicates a significant difference between species, after a G-test. B Mean tonic immobility duration in seconds for each terrestrial isopod (considering all stimuli pooled) in experiment 1. Different letters indicate significant differences, after ANOVA and Tukey test.

Regarding the different stimuli, Porcellio dilatatus was responsive to the three stimuli equally (χ2=1.75; p=0.417), whereas Balloniscus glaber was more responsive to “drop” (χ2=11.703; p=0.003) and Balloniscus sellowii was more responsive to “touch” (Fig. 3A) (χ2=7.882; p=0.019). The proportion of responsive males and females did not differ in all species (Porcellio dilatatus χ2=0.111; p=0.73; Balloniscus glaber χ2=0.812; p=0.36; Balloniscus sellowii χ2=0.008; p=0.92) (Fig. 3B).

A Percentage of responsive individuals to each specific stimulus, in relation to the total number of responsive individuals of each species. B Percentage of responsive males and females in relation to the total number of males and females of each species tested. The * indicates a significant difference between stimuli, after a χ2 test.

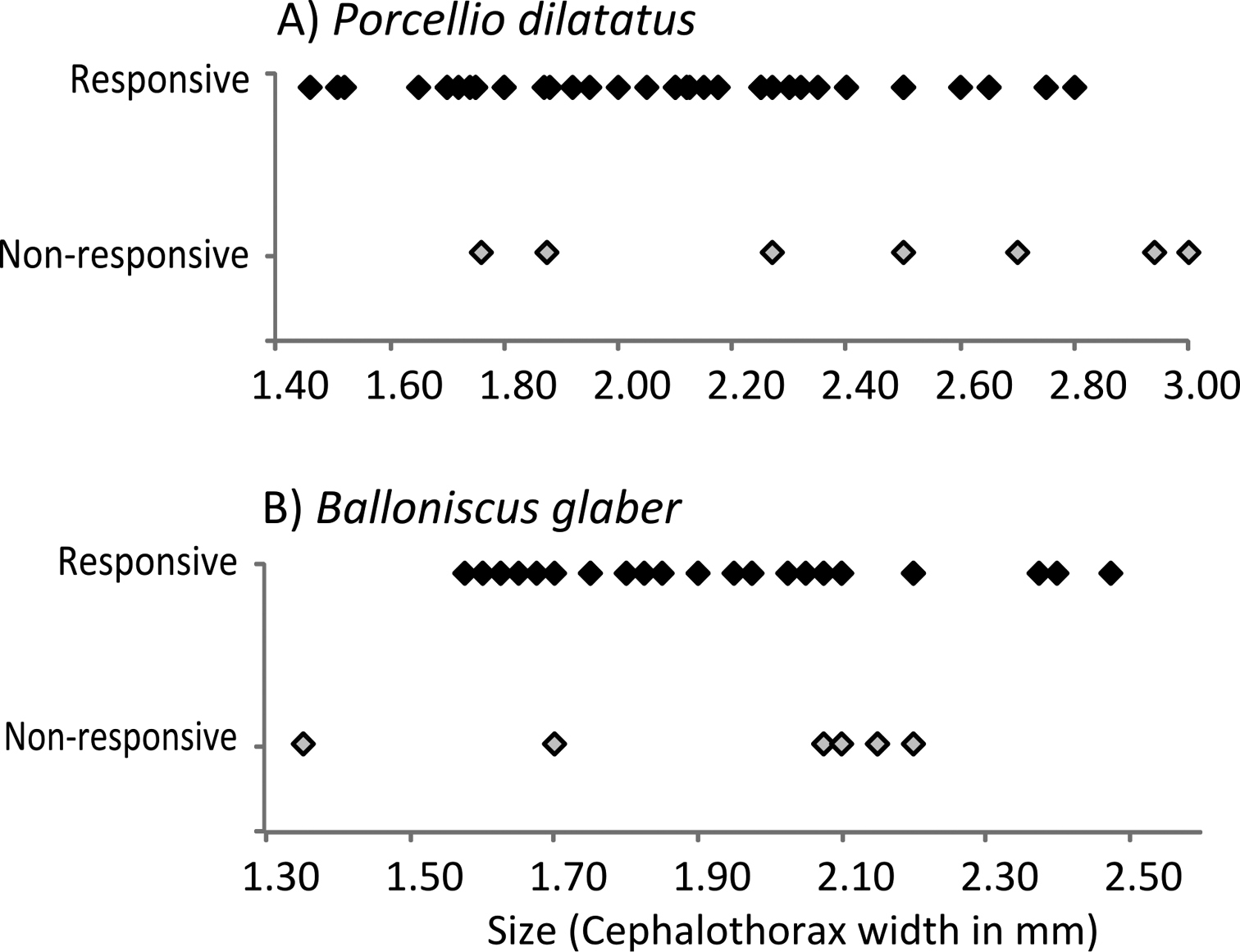

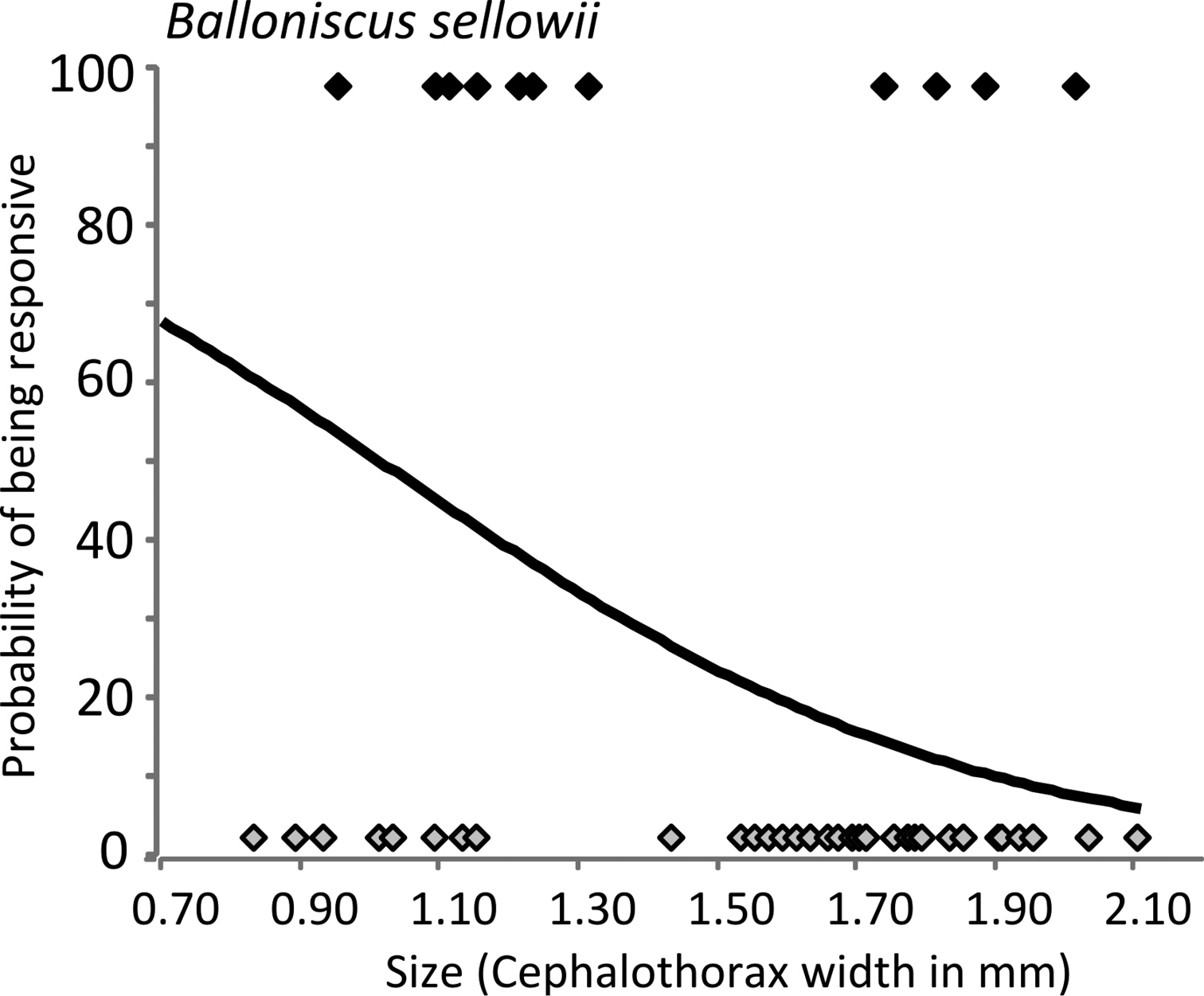

In relation to size, an interesting trend was observed. In Porcellio dilatatus and Balloniscus glaber, responsiveness was independent of individual size. As mentioned above, most individuals of these species were responsive (Fig. 4). In Balloniscus sellowii, however, there were intraspecific differences in responsiveness: a fitted logistic regression indicated that the probability of being responsive is higher in younger individuals and decreased with size (=age) (Fig. 5) (Logistic regression: Model intercept=3.254; s.e.=1.39; p=0.019; Size (factor) = -2.821; s.e.= 0.951; p=0.003; AIC=60.21).

Size and response to the stimuli in A Porcellio dilatatus and B Balloniscus glaber. Responsive individuals are represented with black marks and non-responsive individuals with grey marks.

The duration of tonic immobility was highly variable in all trials: it ranged from a few seconds up to 3 min in Porcellio dilatatus, 7 min in Balloniscus sellowii and up to 12 min in Balloniscus glaber. The duration of response differed between species (Fig. 2B), but the effect of the different stimuli was not significant (Table 1). Porcellio dilatatus remained in tonic immobility for a shorter time interval than the two Balloniscus species (Fig. 2B).

Differences in the duration of tonic immobility depending on the species and different stimuli.

| ANOVA results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | d.f. | SS | MS | F | p |

| Species | 2 | 8.91 | 4.45 | 13.36 | p<0.001 |

| Stimuli | 2 | 0.93 | 0.46 | 1.39 | p=0.250 |

| Residuals | 190 | 63.34 | 0.33 | ||

Using ANCOVA we verified that neither sex nor size of the isopods explained the variation found in the duration of tonic immobility (Table 2).

Relationship between the duration of tonic immobility and individual size (cephalothorax width in mm) and sex (co-variable).

| ANCOVA results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | d.f. | SS | F | p |

| Porcellio dilatatus | ||||

| Size | 1 | 0.143 | 0.587 | 0.44 |

| Sex | 1 | 0.836 | 3.426 | 0.07 |

| Size:Sex | 1 | 0.147 | 0.602 | 0.44 |

| Residuals | 37 | 9.035 | ||

| Balloniscus glaber | ||||

| Size | 1 | 0.052 | 0.226 | 0.63 |

| Sex | 1 | 0.287 | 1.248 | 0.27 |

| Size:Sex | 1 | 0.019 | 0.085 | 0.77 |

| Residuals | 27 | 6.215 | ||

| Balloniscus sellowii | ||||

| Size | 1 | 0.366 | 1.127 | 0.30 |

| Sex | 1 | 0.514 | 1.582 | 0.22 |

| Size:Sex | 1 | 0.516 | 1.583 | 0.22 |

| Residuals | 16 | 5.205 | ||

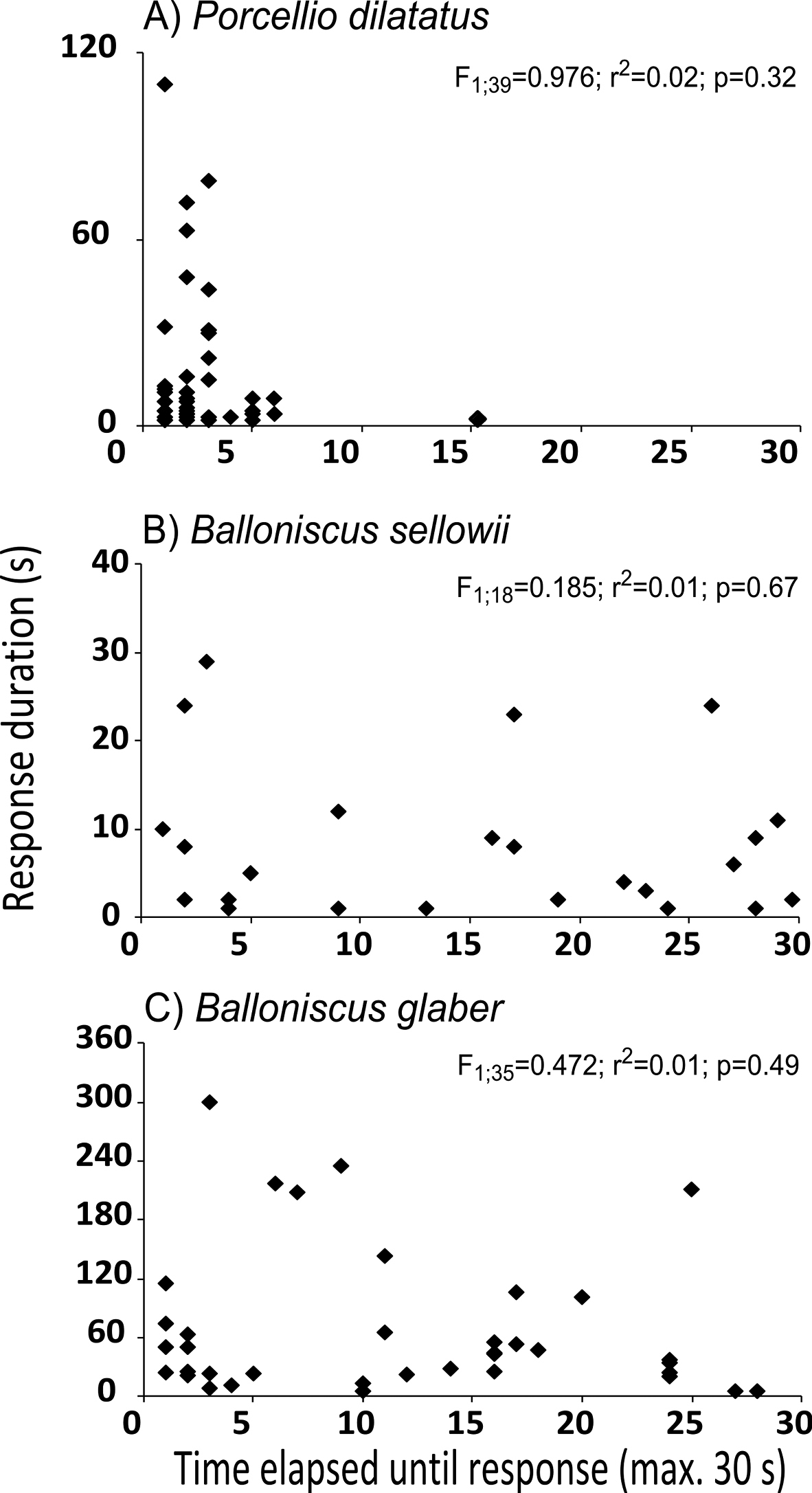

In this experiment, 77% Porcellio dilatatus, 65% Balloniscus glaber and 34% Balloniscus sellowii individuals responded to the stimulus within the 30 seconds. Upon visual inspection of data in Fig. 6 it can be seen that for none of the species there was a relationship between the time elapsed until tonic immobility and the duration of the response, which was confirmed with the linear regression analysis (see Fig. 6). In the case of both Balloniscus species there were individuals that responded promptly (in less than 5 s) or took more than 20 s to respond and remained in tonic immobility for short time intervals (less than 10 sec) and long time intervals (4 to 5 min). In all species tonic immobility duration was highly variable among individuals and it was independent of the time that each individual took to respond (Fig. 6). However, it can be noted a different pattern of response in Porcellio dilatatus: 99% of the responsive individuals responded within 7 s of stimulation (Fig. 6).

Responsiveness of Balloniscus sellowii individuals in relation to size. The line models the probability of being responsive according to the individual size (after a logistic regression). The black and grey symbols show the responsive and non-responsive individuals, respectively.

Relationship between the time elapsed until the beginning of tonic immobility and the duration of response, for responsive individuals in experiment 2. The values indicate the results of the linear regression analysis.

In this study we used two intrinsic factors (sex and size of the individuals) and one extrinsic factor (different stimuli) to try to explain the intraspecific variability found with respect to the responsiveness and duration of the tonic immobility showed by terrestrial isopods. We found an influence of the size in the responsiveness of Balloniscus sellowii and an influence of the type of stimulus in both Balloniscus species. Regarding the duration of tonic immobility, none of the factors explained the variability exhibited by the individuals. These findings are discussed below in more detail.

Males and females of different species are known to differ in responsiveness and duration of tonic immobility. For instance, in the beetle Callosobruchus maculatus (Fabricius) the females had a significantly higher frequency and longer duration of tonic immobility than males (Myatake et al. 2008a). In the freshwater crab Trichodactylus panoplus von Martens females stayed immobile for longer time than males (

Upon encounter with a predator, a prey may run or enter tonic immobility, but it cannot adopt both strategies at the same time (

Among the extrinsic factors that are known to influence responsiveness to tonic immobility-inducing stimuli, temperature (

Tonic immobility duration varies widely intraspecifically. For instance,

In conclusion, we observe three different patterns of tonic immobility among the clingers studied. Balloniscus sellowii enters tonic immobility rarely, it is more likely to adopt an active defense, such as running. Balloniscus glaber is more responsive, irrespective of the stimulus applied, the sex or size of the individuals, and can stay in tonic immobility for a long time, which indicates that tonic immobility could be an important strategy for this species. Porcellio dilatatus is highly responsive, also irrespective of the stimulus applied, the sex or size of the individuals, but it shows a much shorter response. As pointed by

The authors are thankful to Dr. Mark Hassall for his helpful insights on an earlier version of the manuscript and for the suggestions of two referees that greatly improved the quality of the final version. We thank Dr. Catherine Souty-Grosset for kindly providing the picture of Porcellio dilatatus. The authors are also indebted to Capes for the scholarship granted to P. Bugs. This study was accomplished with the support of CNPq Brasil (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) through a Post-doc scholarship granted to AF Quadros and grants given to PB Araujo (Productivity Fellowship).