(C) 2012 Ferenc Vilisics. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

A series of experiments were applied to test how leaf orientation within microcosms affect consumption rates (Experiment 1), and to discover intra-specific differences in leaf litter consumption (Experiment 2) of the common isopod species Porcellio scaber and Porcellionides pruinosus. A standardised microcosm setup was developed for feeding experiments to maintain standard conditions. A constant amount of freshly fallen black poplar litter was provided to three distinct size class (small, medium, large) of woodlice. We measured litter consumption after a fortnight. We maintained appr. constant isopod biomass for all treatments, and equal densities within each size class. We hypothesized that different size classes differ in their litter consumption, therefore such differences should occur even within populations of the species. We also hypothesized a marked difference in consumption rates for different leaf orientation within microcosms. Our results showed size-specific consumption patterns for Porcellio scaber: small adults showed the highest consumption rates (i.e. litter mass loss / isopod biomass) in high density microcosms, while medium-sized adults of lower densities ate the most litter in containers. Leaf orientation posed no significant effect on litter consumption.

Porcellio scaber, Porcellionides pruinosus, microcosm experiment, litter consumption, leaf orientation

Ecosystem processes, such as decomposition, are greatly influenced by the taxonomic and functional diversity of assemblages (

Confirming the statements above, studies suggest significant intra-specific divergence in the diet of soil macro-arthropods through their isotopic signatures (

Here, we focus on intra-specific differences in food consumption of terrestrial isopod species. Woodlice are relatively long-lived invertebrates that belong to the same guild (soil- and litter-dwelling macro-decomposers) in every life stage: manca, juvenile, pre-adult, adult. Isopods are effective decomposers (e.g.

Decomposition through isopods is a phenomenon rather frequently studied, particularly in laboratory experiments (e.g.

In our experiments we focused on distinct size classes of isopods. Intra-population variation in body size (especially between medium-sized and large adults) may also be explained by distinct life history patterns. As such, cohort-splitting is a phenomenon by which some individuals of a certain cohort grow slowly while others grow faster. Young males and females may grow differently, e.g. invest more in growth than reproduction in the early periods (e.g.

Distinct isopod size classes, whether they are related to true age differences or cohort-splitting, may also differ in leaf litter utilization. This assumption is based on the idea that different size classes probably show differences in their feeding preferences – due to their anatomical features, e.g. ontogenic development in mouth parts, mandible morphology (

We conducted preliminary observations to detect how leaf orientation affects decomposition rates. We assumed that structural differences of the abaxial and adaxial sides of leaves will show distinctions in decomposition patterns. Isopods aggregate under logs and leaf litter to hide, mate and feed (

Choosing species-poor ecosystems (e.g. urban areas) as model for our studies, we aimed to see how different size classes of frequent urban species, Porcellio scaber and Porcellionides pruinosus Brandt, 1833, contribute to litter mass loss in laboratory experiments. For Porcellio scaber we used two different sets of experiments applying different densities for each size classes.

In this paper we also present a detailed description of microcosm setup and experimental design. We added some new features such as a multi-layer plaster system to maintain constant humidity, and standard order of leaf orientation to avoid biases from selective feeding.

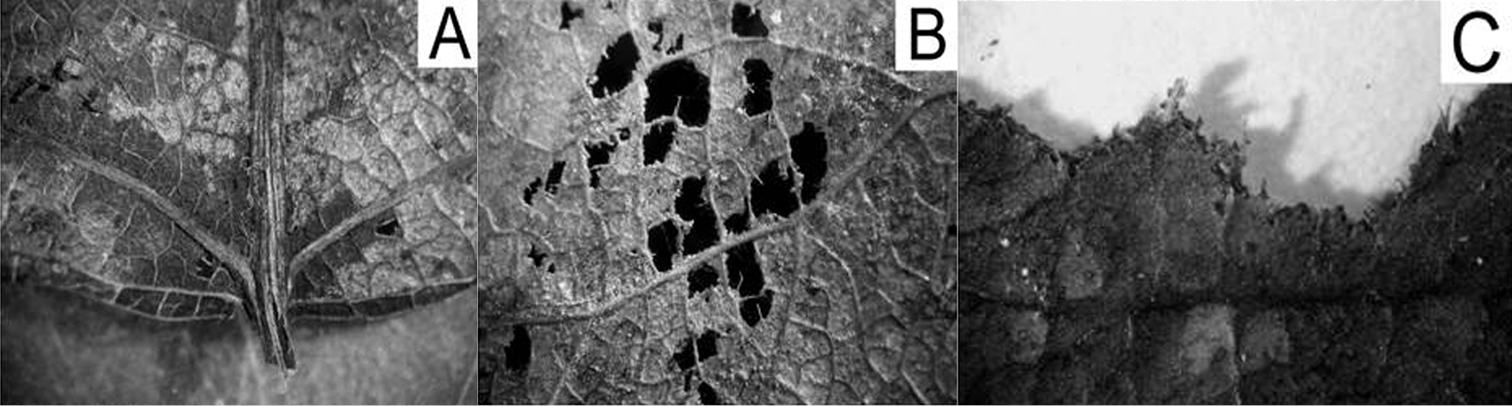

HypothesesA pilot study showed differences in litter degradation patterns among size classes of Porcellio scaber: small bodied pre-adults primarily fed on leaf tissues amongst small veins, leaving vascular tissues and plant cuticle intact. Medium-sized adult individuals ate smaller veins and tissues, while large adults made no visible distinction in their choice (Fig. 1). Based on that observation, we assumed differences in litter consumption, too.

Patterns of litter degradation by Porcellio scaber size classes on poplar litter. A=small (0.2-0.5 mm in length), B=medium (0.7 – 10 mm), C=large (10 – 15 mm) isopods.

First, we hypothesize that leaf orientation affects consumption rates, explained by the general differences between abaxial and adaxial sides of tree leaves. We assume greater mass loss of leaves with abaxial side exposed, as abaxial side has thinner plant cuticle and protective layers (wax, hairs) than adaxial side.

Secondly, we hypothesized larger adults to consume more poplar litter due to their seemingly wider spectrum of food sources compared to the smaller ones.

MethodsTo test our two hypotheses, two separate microcosm experiments were set up. We established controlled conditions at the Institute for Biology at Szent István University, Budapest. To maintain constant humidity and temperature, we built a tent out of transparent plastic sheets and a wooden frame (5 m in length, 3 m in width, 2 m in height). The inner mean temperature was 19 ºC (SD±0.7), average relative air humidity was 68% (min. 61%, max 72%). We set a light regime of 12 / 12 hours of night and day.

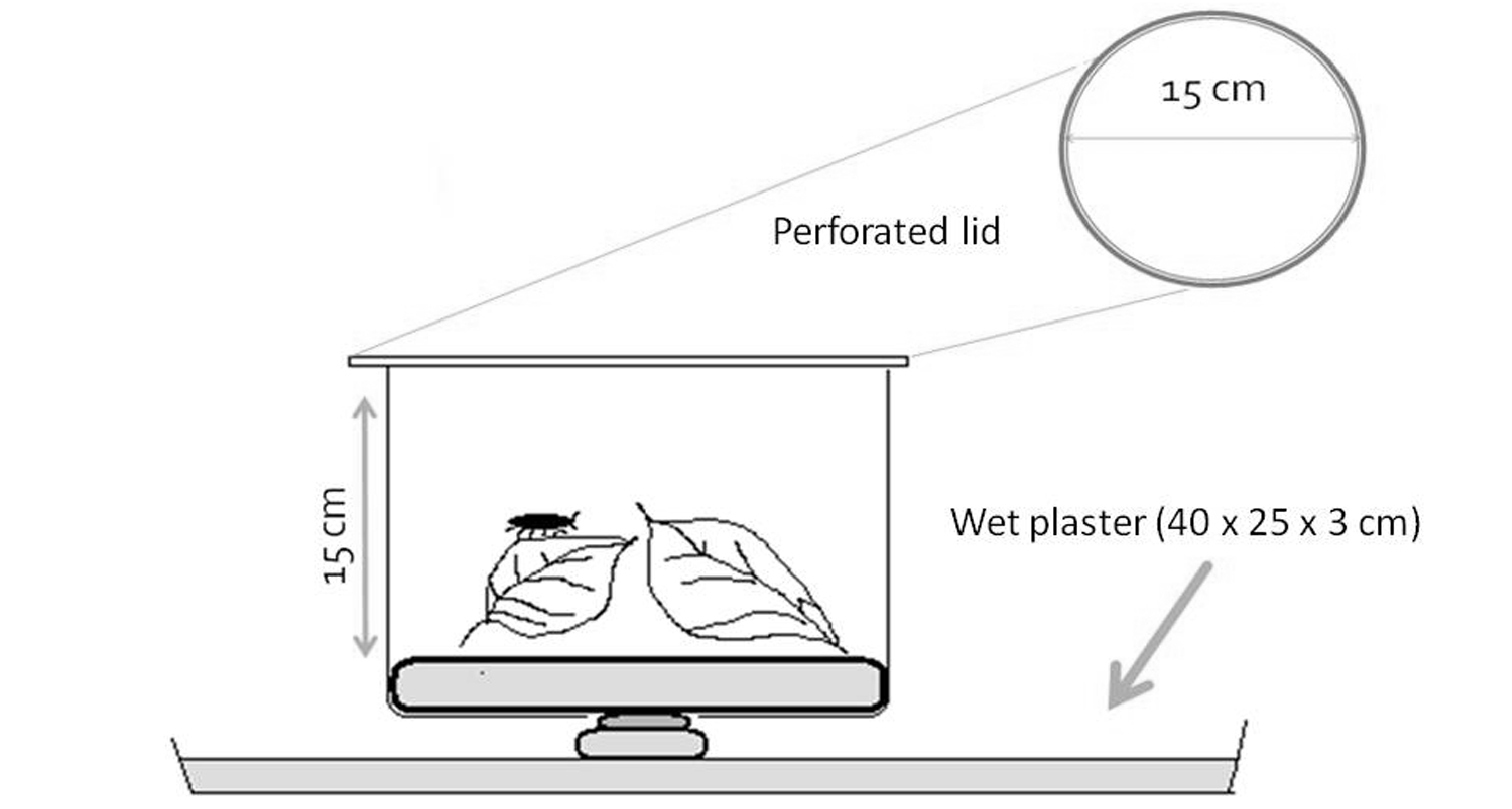

MicrocosmsFor the experiments we used a set of microcosms assembled in the same way (Fig. 2). We used transparent poly-ethylene containers of 15 cm in height and 15 cm in diameter, with removable lids perforated for air exchange. To maintain constant humidity, we applied layers of plaster of Paris.

Schematic figure of a microcosm showing dimensions of the transparent plastic container and the plaster layer underneath.

Solid plaster has already proven to be useful in laboratory experiments (e.g.

The humidity system consisted of three layers of plaster of Paris: a 3 cm thick bottom layer, a 0.5 cm bridging layer and a 1 cm thick contact layer. Plastic trays (bottom layer), shallow cups (bridging layer) and the containers for microcosm (contact layer) served as mold casting (see Fig. 2 for details).

The bottom layer was a slab of 40 cm x 30 cm plaster molded in a plastic tray watered directly. A hole was carved from one corner to monitor water level. As this layer should be always loaded with water, refill was necessary every second days (ca. 1.5 L / tray). As water does not always distribute evenly within plaster, it is important to maintain even surfaces.

The bridging layer, a thin disc of plaster, was placed between the watery bottom layer and the contact layer within the container. This layer was attached to the bottom of each container and transferred water to the contact layer through a hole cut on the bottom of each container. The bridging layer was glued to the contact layer by plaster. The contact layers, molded from microcosm containers, therefore precisely fit, were the solid grounds for isopods where litter consumption took place.

As preliminary studies showed a tendency for cannibalism (approx. 5% mortality), we decided to apply inedible shelters. For this purpose we used non-translucent rubber tubes (2 cm long, 0.5 cm diameter), 3 pieces in each container. Microcosms were placed randomly on trays of bottom layers.

Leaf litterFor both experiments we used leaf litter of Populus nigra L. collected one week after fall and stored in the lab under dry conditions.The chosen tree species is common in Hungarian urban green spaces and floodplain forests. Leaf litter was collected from a major park (Városliget) in Budapest. We used leaves of similar stage of decay: surface and edge were unbroken, the colour was brown. After washing off the dust, we removed the petioles from the leaves. Litter was oven dried at 60°C for 20 hours. Litter processing varied between experiments as described in sub-chapters below.

Test speciesWe chose the common rough woodlouse Porcellio scaber and Porcellionides pruinosus as test species for our experiments. Porcellio scaber is a frequently used organism of laboratory research (e.g.

Porcellio scaber individuals were collected in an enclosed garden in Hajdúböszörmény for Experiment 1, and in central Budapest for Experiment 2. Individuals of Porcellionides pruinosus were collected from a compost heap in the park of the Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Szent István University, Budapest.

As isopods gut content may differ, we attempted to let the animals empty their guts without refilling it. All animals were starved for two days and weighed before and after the experiment with a digital analytical scale.

It is known that a single population may produce great annual, or even seasonal variations (e.g.

To test our hypotheses on leaf litter consumption we used Mood’s median test as implemented in R (

To reveal the effects of different leaf orientation (adaxial side up or down) in litter consumption experiments, we placed standard discs (ca 2 cm in diameter) cut from Populus nigra leaves in microcosms (c.f.

To the experiment either five Porcellio scaber (size >1 cm, 238 mg ± 5 mg) or five Porcellionides pruinosus (cca. 0.5 cm, 71 mg ± 2 mg) adult individuals were used per container.

Experiment 2: Intra-specific, size dependent litter consumption ratesTo each microcosm we added 1500 mg (± 1 mg) of poplar leaves, three pieces per container. As we supposed that litter orientation biases consumption rates, we arranged leaves in a standard order: 1st leaf abaxial side down, 2nd leaf adaxial side down, 3rd leaf abaxial side down, etc.

Litter dry mass was measured by a digital analytical scale at the start, and after 14 days of experimental period (with 12 hours light-dark regime). Faecal pellets and dirt were brushed off prior to final weighing after oven-drying (60 °C) for 20h.

Out of the collected individuals we selected three distinct size classes (small: 3-5 mm, medium: 7-11 mm, large: >15 mm).

Within Experiment 2, we used two experimental settings by using different isopod densities within microcosms. We attempted to use similar numbers of isopod individuals in similar weights at each size class per each replicate (microcosm). Mean numbers, biomasses and the number of microcosms used in our experiments are shown in Table 1.

Mean (±SD) number of isopod individuals, their cumulated biomasses and the number of microcosms used in the experiments.

| Size category | Experiment 2/a | Experiment 2/b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcellionides pruinosus | Porcellio scaber | Porcellio scaber | |||||

| Small | No. of ind. | 20 | (SD±0) | 12 | (SD±0) | 51 | (SD±5.9) |

| Biomass (mg) | 82.5 | (SD±1.87) | 224.3 | (SD±14.76) | 301.1 | (SD±2.76) | |

| Medium | No. of ind. | 10 | (SD±0) | 6 | (SD±0) | 8.9 | (SD±0.76) |

| Biomass (mg) | 85 | (SD±3.35) | 166 | (SD±2.74) | 303.7 | (SD±8.67) | |

| Large | No. of ind. | 5.2 | (SD±0.24) | 3 | (SD±0) | 4.7 | (SD±0.23) |

| Biomass (mg) | 83.5 | (SD±2.26) | 232.8 | (SD±11.29) | 299.9 | (SD±2.89) | |

| Number of microcosms analysed | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||

Legend: No. of ind. = Number of individuals within microcosms; Biomass = isopod biomass (mean±SD) within microcosms

At Experiment 2/a we attempted to keep isopod biomass constant at around 200 mg in each microcosm, regardless to size classes. Whereas in Experiment 2/b we used only Porcellio scaber individuals in densities higher than in Exp. 2/a. In this case, isopod biomass was kept at around 300 mg in each microcosm for all size classes.

Data of containers with a mortality rate higher than 20% were omitted from analyses. In order to keep similar sample sizes, we had to omit data from other size classes as well (even if their mortality rate was lower than 20%). In such cases we used a random number generator by which we selected data for deletion. This practice has also resulted in differences in numbers of replicates among Experiments, as seen on Table 1.

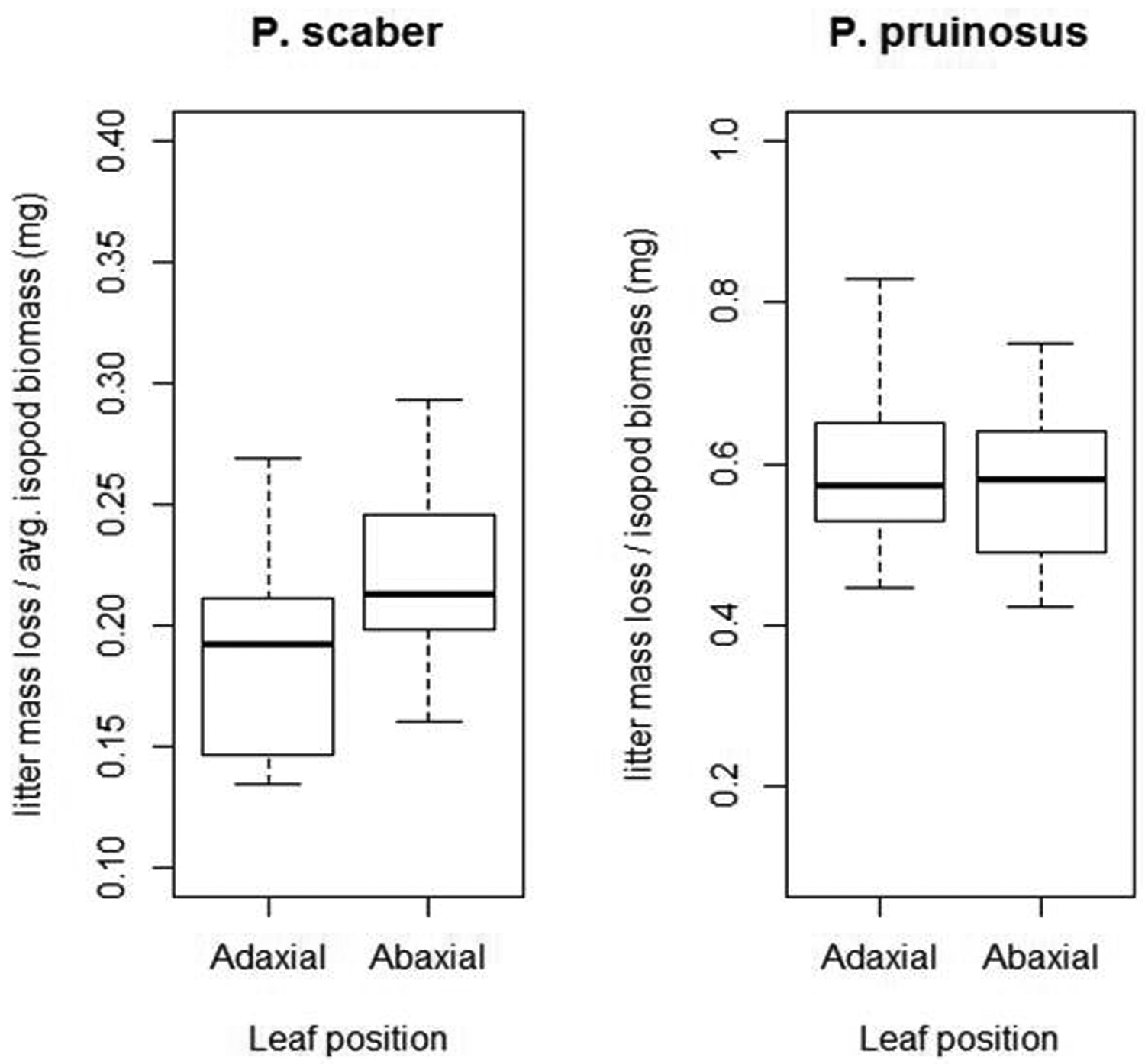

Results Experiment 1: Effects of leaf orientation on litter consumptionWith Porcellio scaber we found visible, albeit not significant (Mood’s median test, p=0.11), differences in litter mass loss (Fig. 3). Similarly, Mood´s median test revealed no significant effect of leaf orientation on the litter consumption rates of Porcellionides pruinosus (p=1).

Effects of leaf litter positioning (abaxial up vs. abaxial down) on litter consumption of two isopod species. Note the different scaling of y axes. Legend: P. pruinosus: Porcellionides pruinosus; P. scaber: Porcellio scaber; Adaxial = adaxial side up; Abaxial = abaxial side up; Thick line = median; box = lower and upper quartiles; whisker = min. and max values.

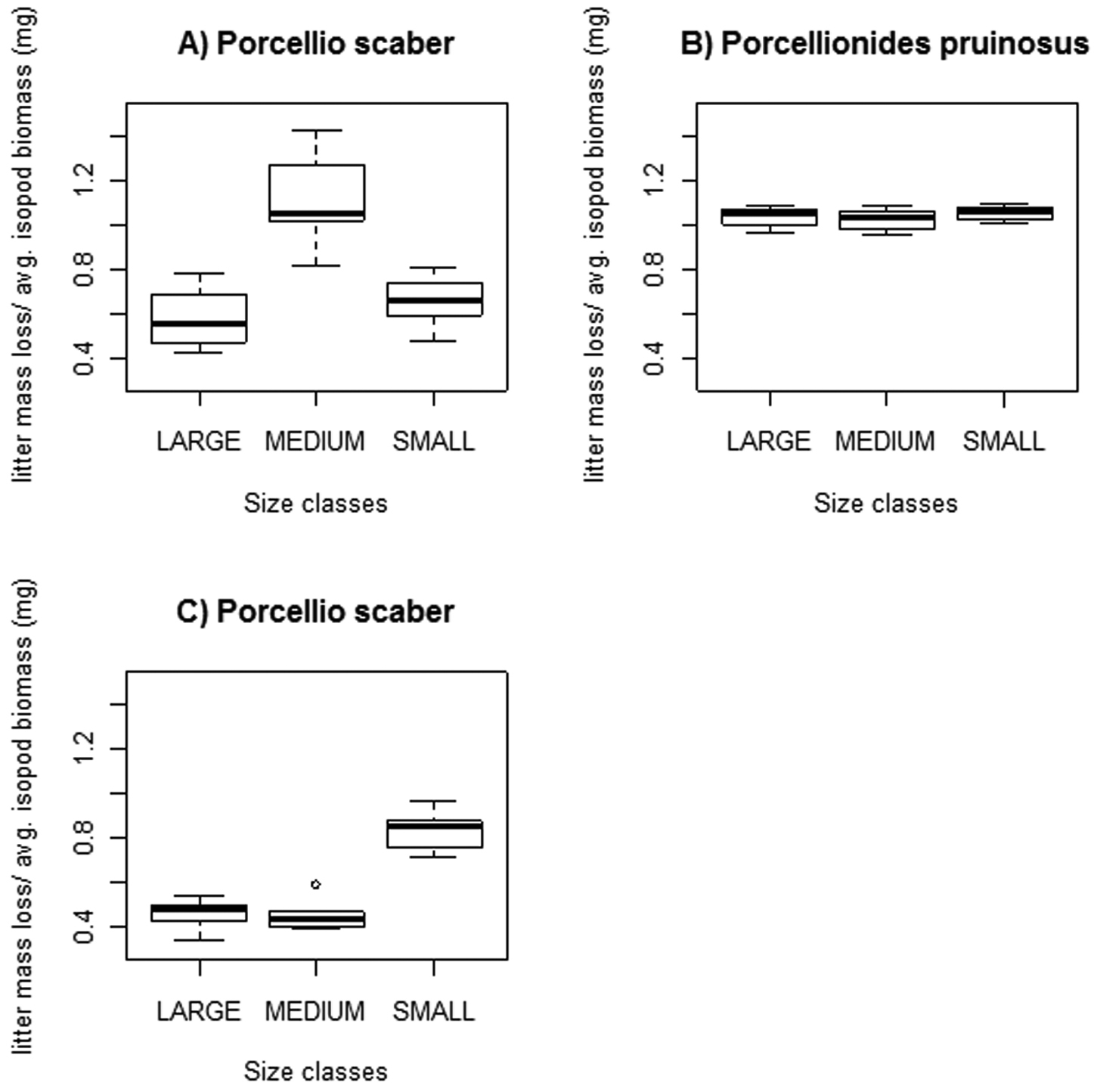

Litter mass loss differed among the three size classes of Porcellio scaber at both experimental sets (2/a, b), while no significant differences were found among classes of Porcellionides pruinosus. Figure 4 shows the main results: A and B represent Experiment 2/a, while C represents Experiment 2/b.

Freshly fallen poplar litter consumption of three size classes of Porcellio scaber and Porcellionides pruinosus. Legend: Thick line = median; box = lower and upper quartiles; whisker= min. and max values; open circles: outliers.

In Experiment 2/a (lower Porcellio scaber densities) we measured statistically significant differences between „medium” and both „large” and „small” classes (Fig. 4/A). The latter two categories showed no statistically significant difference in their litter consumption, (p=0.131). Porcellionides pruinosus size classes showed no marked difference in their litter consumption (p=1).

In Experiment 2/b (the setting with higher Porcellio scaber densities) we measured significant differences between the „small” and both „medium” and „large” classes (Mood’s median test, p<0.001), while the two larger categories showed no significant difference (p=1).

All Porcellionides pruinosus size classes consumed, in general, ca. 1 mgleaf / 1 mgisopod, while this rate was less in most Porcellio scaber size classes in both experimental settings (Fig. 4).

DiscussionThe study proved that (with the current setup) leaf orientation do not have significant effect on leaf litter consumptions. Isopod size classes, to certain degrees however, can bias leaf litter consumption rates in microcosm experiments.

It is evident that at this stage of our research we are unable to explain the reasons of the patterns we got. Therefore we devote most of this chapter to speculations.

Leaf orientation, which had - to the best of our knowledge - never been studied before, has proven to pose no effect in biasing consumption rates. Our approach applies for microcosm experiments using small number of leaves (cc. 1–3) where „random” arrangement is not possible. We assume that greater differences would appear in consumption rates between the two sides as soon as isopods could reach the bottom of leaf litter. Woodlice normally hide under dead plant matter, using it as shelter and food source at the same time (

Leaves exposed to sun are large and thin while small and thick leaves develop in the shade (e.g.

Opposite to our hypothesis, large Porcellio scaber individuals ate relatively less than smaller adults. In fact, large adults consumed very little of the leaf litter. For this reason we suspect that the primary food source of this species may be something more palatable than freshly fallen (or near-freshly fallen) litter. The relatively large consumption rates for smaller (small- and medium-sized) adults is probably explained by their higher metabolism induced by intense growth. This agrees with the findings of

Our results with Porcellio scaber suggest that mainly the small individuals contribute in the comminution process of leaf litter. This function may be especially valuable in areas with low soil activity and species poor decomposer fauna, such as urban areas (e.g.

Besides the effects of size classes, we have also shown results more likely related to densities (individuals per container) than isopod sizes (

With these results, we would like to show some details that can, to some degree, bias results in laboratory experiments. In order to provide more reliable results in microcosm experiments we suggest standardizing the size and density of isopods.

The authors thank Dr. Péter Szabó and Dávid Fülöp for their valuable contributions to practical and theoretical challenges during the experiments. Our project was funded by NKB ÁOTK 15942. The authors would like to thank the Referees for their detailed review and helpful comments.