(C) 2011 Radomir Jaskuła. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

This paper summarizes the current knowledge on winter active Carabidae in Central and Northern Europe. In total 73 winter active species are listed, based on literature and own observations. Ground beetles are among the three most numerous Coleoptera families active during the autumn to spring period. The winter community of Carabidae is composed both of larvae (mainly autumn breeding species) and adults, as well as of epigeic species and those inhabiting tree trunks. Supranivean fauna is characterized by lower species diversity than the subnivean fauna. The activity of ground beetles decreases in late autumn, is lowest during mid-winter and increases in early spring. Carabidae are noted as an important food source in the diet of insectivorous mammals. They are also predators, hunting small winter active invertebrates.

Coleoptera, Carabidae, Central Europe, winter activity, subnivean fauna

During winter, invertebrates are mostly inactive in diapause as eggs, larvae or pupae, but less often as adult stages (

Snow cover provides winter active animals with three

different microhabitats. The insulating properties of snow make the

space under the snow a favourable habitat for invertebrates (subnivean

microenvironment). The subnivean microhabitat is relatively warm,

humid, thermally stable and protects organisms from wind and lethal

temperatures in contrast to the snow surface (supranivean environment),

which is highly variable and completely dependent on atmospheric

factors. Within the snow, the so-called intranivean habitat,

temperatures are lower but organisms are still protected from the

external environment (

The snow fauna is an ecological group, which consists of

permanent snow active invertebrate species. The first observations

regarding invertebrate activity on the snow was made in Poland in the

middle of 18th century (

The first information about subnivean fauna appeared

almost two centuries later than that of the fauna living on the snow.

The subnivean microenvironment is inhabited by more numerous groups of

invertebrates, such as oligochaetes, molluscs, crustaceans,

arachnids and insects. Among these, insects and spiders clearly

predominate, being the major representatives of the snow active fauna.

The subnivean fauna was studied more often than the snow active fauna.

Main studies came from Canada (

During the last decades, global climate change has become an important scientific topic. However its influence on poikilothermic organisms has been poorly investigated. It seems that the occurrence of snow cover during the winter period plays an important role in the biology of many different invertebrate groups.

The aim of this paper is to summarize knowledge regarding winter active Carabidae fauna from Central and Northern Europe. In the present paper we discuss only the “true winter active” ground beetles, and not members of the nival fauna occurring in high-altitude regions or glaciers.

MethodsWinter season is defined here as the period between the end of November and the beginning of April. All available literature data on winter active Carabidae recorded from Central and Northern Europe were used in this study. In total, data from five countries and published in 17 papers were analyzed (see Table 1). Data of mountain Carabidae active on the snow and glaciers as well as species found overwintering in diapause were not included. In addition, our unpublished records of winter active Carabidae from Central Poland were included. This material was collected occasionally during different field studies using pitfall traps (subnivean species) and active searching on the snow cover. The list of species analyzed in this study is given in Table 1.

All recorded ground beetle species were divided into three groups, according to the microenvironment in which they were noted: epigeic (subnivean), active on the snow cover (supranivean), and actively walking on tree trunks. Data on activity of both the adults and the larvae are also shown in Table 1.

The ecological response towards snow active ground beetle species was done according to

For the nomenclature of Carabidae

species, the Fauna Europea Web Service (2004) was followed, while the

zoogeographical analysis of ground beetles was based on the study by

Most studies performed on winter active ground beetles are rather recent (Table 1). The first faunistic data on winter active Carabidae came from the beginning of 20th century, when five species belonging to the genera Leistus, Bradycellus, Dromius, Ocydromus and Pterostichus were noted in Finland as active on the snow surface by

Compared to supranivean species (which are easier to

observe because of the contrast between the white colour of the snow and

the dark coloured insects), the carabids active under the snow surface

(subnivean fauna) were discovered rather late. First data on subnivean

ground beetles became available after using Barber’s traps as a

collecting method, and in Central and Northern Europe were given from

Germany by

More adult beetles were later collected by

Comparing the two above-mentioned “ecological

groups”, it becomes clear that in the studied area, diversity of the

subnivean carabid fauna is more than five times higher than that of the

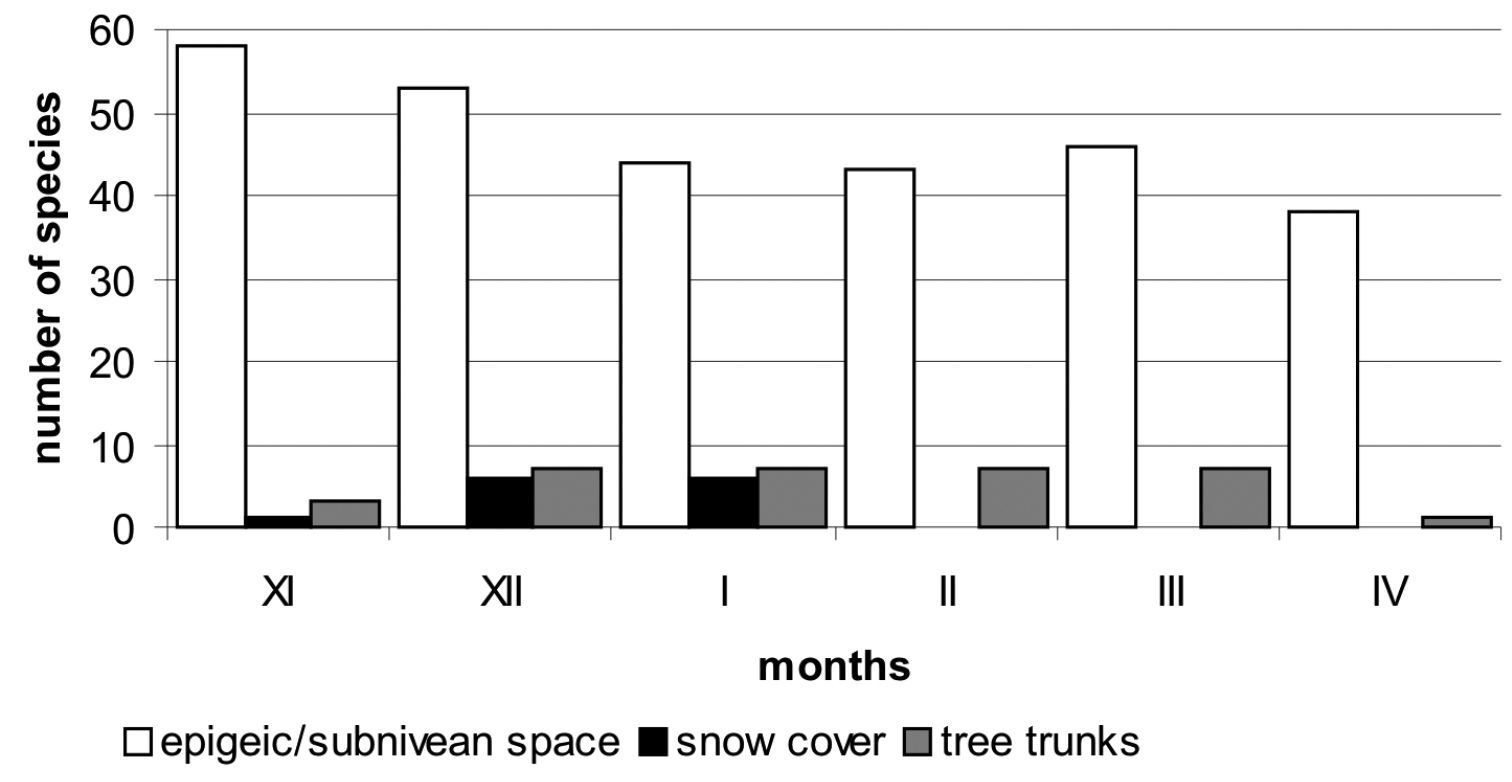

supranivean species (Fig. 1). A similar tendency was observed in Collembola, but was opposite when compared to some other insect groups like Diptera or Mecoptera (

Tree trunks are the third type of microhabitat where winter active Carabidae occur. The only paper on this topic known to us comes from

List of winter active ground beetles (A – adults, L – larvae). Roman letters indicate the month(s) of observation(s). Nomenclature after

| No. | Species | Snow cover | Epigeic (subnivean) | Treetrunks | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abax parallelepipedus (Piller et Mitterpacher, 1783) | A | XI-XII, III-IV |

|

||

| 2 | Abax sp./Pterostichus sp. | L | XI-XII |

|

||

| 3 | Acupalpus dubius Schilsky, 1888 | A | XII |

|

||

| 4 | Agonum gracile Sturm, 1824 | A | IV | this paper | ||

| 5 | Agonum muelleri (Herbst, 1784) | A | I |

|

||

| 6 | Agonum viduum (Panzer, 1796) | A | XI |

|

||

| 7 | Amara aulica (Panzer, 1796) | L | XI-I |

|

||

| 8 | Amara brunnea (Gyllenhal, 1810) | A | XI-XII | this paper | ||

| 9 | Amara communis (Panzer, 1797) | A | XI-XII |

|

||

| 10 | Amara infima (Duftschmid, 1812) | A | XI-I (?) |

|

||

| 11 | Amara familiaris (Duftschmid, 1812) | A | III-IV |

|

||

| 12 | Amara lunicollis Schiødte, 1837 | A | III-IV |

|

||

| 13 | Amara sp. | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 14 | Anchomenus dorsalis (Pontoppidan, 1763) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 15 | Anisodactylus binotatus (Fabricius, 1787) | A | IV | this paper | ||

| 16 | Asaphidion flavipes (Linné, 1761) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 17 | Asaphidion pallipes (Schrank, 1781) | A | IV | this paper | ||

| 18 | Badister sodalis (Duftschmid, 1812) | A | III-IV |

|

||

| 19 | Bradycellus caucasicus (Chaudoir, 1846) | A | I | XI-I |

|

|

| 20 | Bradycelus harpalinus (Audinet-Serville, 1821) | A | XI-XII | this paper | ||

| 21 | Bradycellus verbasci (Duftschmid, 1812) | A | XI-XII, II-III |

|

||

| 22 | Calathus erratus (C.R. Sahlberg, 1827) | A | XI |

|

||

| 23 | Calathus fuscipes Goeze, 1777 | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| L | XI-IV |

|

||||

| 24 | Calathus melanocephalus (Linné, 1758) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| L | XII-I |

|

||||

| 25 | Calathus micropterus (Duftschmid, 1812) | A | XI | XI-I (?) |

|

|

| 26 | Calathus rotundicollis Dejean, 1828 | A | XI-XII |

|

||

| 27 | Calodromius bifasciatus (Dejean, 1825) | A | XI-III |

|

||

| 28 | Calodromius spilotus (Illiger, 1798) | A | XI-III |

|

||

| 29 | Carabus convexus Fabricius, 1775 | A | XI-III | this paper | ||

| 30 | Carabus coriaceus Linné, 1758 | L | XII-I |

|

||

| 31 | Carabus hortensis Linné, 1758 | L | XII |

|

||

| 32 | Carabus nemoralis O. F. Müller, 1764 | A | I | XI-IV |

|

|

| 33 | Carabus problematicus Herbst, 1786 | A | XI |

|

||

| 34 | Carabus sp. | L | XI-III |

|

||

| 35 | Cychrus caraboides (Linné, 1758) | L | XI-XII, III |

|

||

| 36 | Demetrias atricapillus (Linné, 1758) | A | + |

|

||

| 37 | Dicheirotrichus cognatus (Gyllenhal, 1827) | A | + |

|

||

| 38 | Dicheirotrichus placidus (Gyllenhal, 1827) | A | XII |

|

||

| 39 | Dromius angustus Brullé, 1834 | A | XII |

|

||

| 40 | Dromius quadrimaculatus (Linné, 1758) | A | XI-III |

|

||

| 41 | Dromius schneideri Crotch, 1871 | A | I |

|

||

| 42 | Dyschiriodes globosus (Herbst, 1784) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 43 | Elaphrus cupreus Duftschmid, 1812 | A | III |

|

||

| 44 | Epaphius secalis (Paykull, 1790) | A | XI-I (?) |

|

||

| 45 | Leistus rufomarginatus (Duftschmid, 1812) | A | XI, I-II |

|

||

| 46 | Leistus ferrugineus (Linné, 1758) | A | XI-I (?) |

|

||

| L | I | XI-XII, III-IV |

|

|||

| 47 | Leistus fulvibarbis Dejean, 1826 | A | XI-XII |

|

||

| 48 | Leistus terminatus (Panzer, 1793) | A | XI-II |

|

||

| L | XI-IV |

|

||||

| 49 | Leistus sp. | L | XII | II-III |

|

|

| 50 | Loricera pilicornis (Fabricius, 1775) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 51 | Metallina lampros (Herbst, 1784) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 52 | Nebria brevicollis (Fabricius, 1792) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| L | XI-IV |

|

||||

| 53 | Notiophilus biguttatus (Fabricius, 1779) | A | XII-I | XI-IV |

|

|

| 54 | Notiophilus rufipes Curtis, 1829 | A | XI, I-II |

|

||

| 55 | Notiophilus substriatus C.R. Waterhouse, 1833 | A | XI, I-II |

|

||

| 56 | Ocydromus tetracolus (Say, 1823) | A | XII | XI-IV |

|

|

| 57 | Panagaeus bipustulatus (Fabricius, 1775) | A | IV | this paper | ||

| 58 | Paradromius linearis (Olivier, 1795) | A | XII | XII |

|

|

| 59 | Paranchus albipes (Fabricius, 1796) | A | XI, II-IV |

|

||

| 60 | Philochthus aeneus (Germar, 1824) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 61 | Philochthus biguttatus (Fabricius, 1779) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 62 | Philochthus guttula (Fabricius, 1792) | A | XI, I-IV |

|

||

| 63 | Philorhizus melanocephalus (Dejean, 1825) | A | + | XII |

|

|

| 64 | Phyla obtusa (Audinet-Serville, 1821) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 65 | Poecilus versicolor (Sturm, 1824) | A | XI, I, II |

|

||

| 66 | Pseudoofonus rufipes (De Geer, 1774) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| L | XI-III |

|

||||

| 67 | Pterostichus diligens (Sturm, 1824) | A | XII | IV |

|

|

| 68 | Pterostichus madidus (Fabricius, 1775) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 69 | Pterostichus melanarius (Illiger, 1798) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| L | XI-I | |||||

| 70 | Pterostichus niger (Schaller, 1783) | A | IV | this paper | ||

| 71 | Pterostichus nigrita (Paykull, 1790) | A | XII | XI-XII, II-IV |

|

|

| 72 | Pterostichus oblongopunctatus (Fabricius, 1787) | A | XII, III-IV | this paper | ||

| 73 | Pterostichus quadrifoveolatus Letzner, 1852 | A | XI-XII |

|

||

| 74 | Pterostichus strenuous (Panzer, 1796) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 75 | Pterostichus sp. | L | XI-IV |

|

||

| 76 | Stomis pumicatus (Panzer, 1796) | A | III |

|

||

| 77 | Trechus obtusus Erichson, 1837 | A | XI-XII, III |

|

||

| 78 | Trechus quadristriatus (Schrank, 1781) | A | XI-IV |

|

||

| 79 | Larvae gen. sp. | L | XI-IV |

|

||

| TOTAL | 11 | 66 | 6 | |||

The most common groups among winter active

invertebrates are spiders and insects. Among hexapods, springtails

(Collembola), beetles (Coleoptera), flies (Diptera) and scorpionflies (Mecoptera)

predominate. Beetle activity under snow cover is well documented.

Investigations on winter active fauna in central Poland show that the

supranivean and subnivean insect winter assemblages differ in terms of

percentage contribution of orders, as well as in species composition.

Beetles have only a share of 13% in snow active insect communities, and

25% in material collected under the snow (

In general, the winter activity of Carabidae

varies seasonally. Its peak – both according to the number of species

and individuals – is observed in late autumn and early spring. The

lowest activity is observed in mid-winter (Fig. 1).

Current analysis suggests that the diversity of ground beetles that are

active under the snow cover is even several times higher than in

supranivean fauna. The number of subnivean species active during the

winter can be similar for months, whereas supranivean carabids occur

more accidentally. As can be seen from Table 1,

only a few species are regularly observed as being active during the

whole winter and from many regions. For most species described as winter

active only one observation of a single individual is recorded. A good

example comes from a study by

According to literature data, winter active carabid

species are known both from forests and open habitats as well as from

species living on tree trunks (Table 1). Moreover,

In general, Carabidae

can be divided into two main breeding groups: autumn breeders (eggs are

laid during the last weeks of summer and first weeks of autumn) and

spring breeders (eggs are laid from March to May). As a result of this

division, winter and summer carabid larvae can be distinguished (

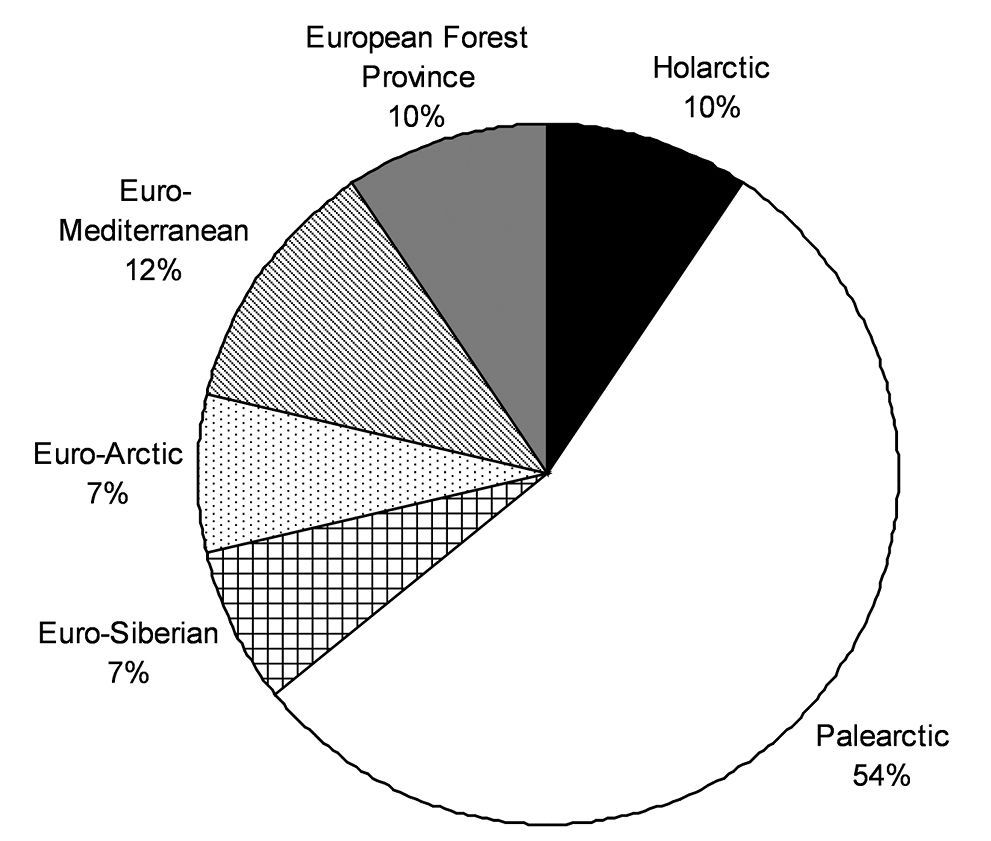

A zoogeographical analysis shows that the Central and northern European winter active Carabidae most frequently belong to the Palaearctic fauna (54%). Interesting is that Euro-Siberian and Euro-Arctic species (groups that should be adapted evolutionary to low temperatures) made up only 14% of the recorded ground beetle species, while 12% of the species belong the Euro-Mediterranean fauna (Fig. 2).

Comparision of subnivean, supranivean and tree trunk fauna of Carabidae from Central and Northern Europe during the winter season (based on different sources).

High densities per square meter and high percentages of Carabidae

in winter active insect communities make this group an important source

of food for insectivorous vertebrates, particularly shrews. Due to

their very high metabolic rate these mammals must feed almost constantly

to stay alive. They are active all year round, without a hibernation

period in winter and their food requirement is 43% higher in winter than

in summer (

From the winter active Central and North European group of Carabidae, 79% of the species appear to be predators (Table 1). Among them there are both large zoophagous species hunting for various types of prey (e.g., Carabus species) and specialists collecting small but very abundant prey items, i.e., springtails and aphids (e.g.,

Many Carabidae species can change their diet according to the availability of food in the environment. Some predatory beetles (e.g., some Carabus species, Pterostichus melanarius, Calathus fuscipes, Nebria brevicollis) occasionally eat plant material. Also some typically phytophagous species (Amara spp., Harpalus spp., Bradycellus spp.) are able to change their diet to eggs and pupae of flies (

An important adaptation that protects winter active

arthropods from freezing is non-feeding behaviour during lower

temperatures (

The relative zoogeographical structure of winter active Carabidae (based on

Based on literature data we can assume that the activity of Carabidae species decreases in late autumn. Activity will be lowest during the winter period, and increases in the early spring (e.g.,

In the literature there are almost no data on the effects of weather factors on winter active Carabidae. A study by

Interesting observations were made by Haning et al. (2006), who noted Calodromius bifasciatus to be active on tree trunks at -3°C and from -1 to +10°C, with males preferring lower temperatures than females (see also

Present knowledge on winter active Carabidae from Central and Northern Europe is rather poor. Literature data are mostly from a few old papers, and usually were fragmentary. In total, 73 species have been recorded as active in winter, including 11 species belonging to 10 genera found on the snow surface, and 66 species from33 genera being subnivean. Four species were recorded for the first time as snow active and one as a subnivean carabid.

Ground beetles are one of the dominating Coleoptera groups in winter insect assemblage. The community of winter active Carabidae is composed of larvae and adult beetles, and consists of both epigeic species and species active on tree trunks. In general, winter active larvae are representatives of autumn breeders. A comparison of the supranivean and subnivean carabid fauna shows significant differences in species diversity. In the first group the number of species are five times lower than in the latter. It suggests that snow active species appear in supranivean microhabitats only accidentally, but they are known to be winter active in litter or soil environments. They should probably be classified as chionoxenes.

Winter activity of ground beetles decreases in late autumn, is lowest during mid-winter and increases in early spring. This might be correlated with weather conditions, especially air temperature. The present state of knowledge suggests that further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The high proportion of Carabidae in winter communities make this group an important food source in the diet of insectivorous mammals, especially shrews. On the other hand these carabids are predators, hunting springtails and other small winter active invertebrates.

We would like to thank Michał Grabowski (University of Łódź) and two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments.