(C) 2011 Robert Mesibov. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

The parapatric boundary between Tasmaniosoma compitale Mesibov, 2010 and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum Mesibov, 2010 (Polydesmida: Dalodesmidae) in northwest Tasmania was mapped in preparation for field studies of parapatry and speciation. Both millipede species can be collected as adults throughout the year, are often abundant in eucalypt forest and tolerate major habitat disturbance. The parapatric boundary between the two species is ca 100 m wide in well-sampled sections and ca 230 km long. It runs from sea level to 600-700 m elevation, crosses most of the river catchments in northwest Tasmania and several major geological boundaries, and one portion of the boundary runs along a steep rainfall gradient. The location of the boundary is estimated here from scattered sample points using a method based on Delaunay triangulation.

Diplopoda, Polydesmida, Dalodesmidae, millipede, Australia, Tasmania, parapatry, boundary estimation, Delaunay triangulation

Millipedes commonly form lineage mosaics (

It is not yet known how the tight parapatry seen in these mosaics originates and is maintained (

I document below a remarkable parapatric boundary of the ‘environmentally incongruent’ kind between two congeneric millipedes in northwest Tasmania. I also demonstrate a simple analytical method for estimating and visualising the location of a parapatric boundary from point localities.

Materials and methods Millipede speciesThe endemic Tasmanian species Tasmaniosoma compitale Mesibov, 2010 and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum Mesibov, 2010 were named, described and provisionally mapped in

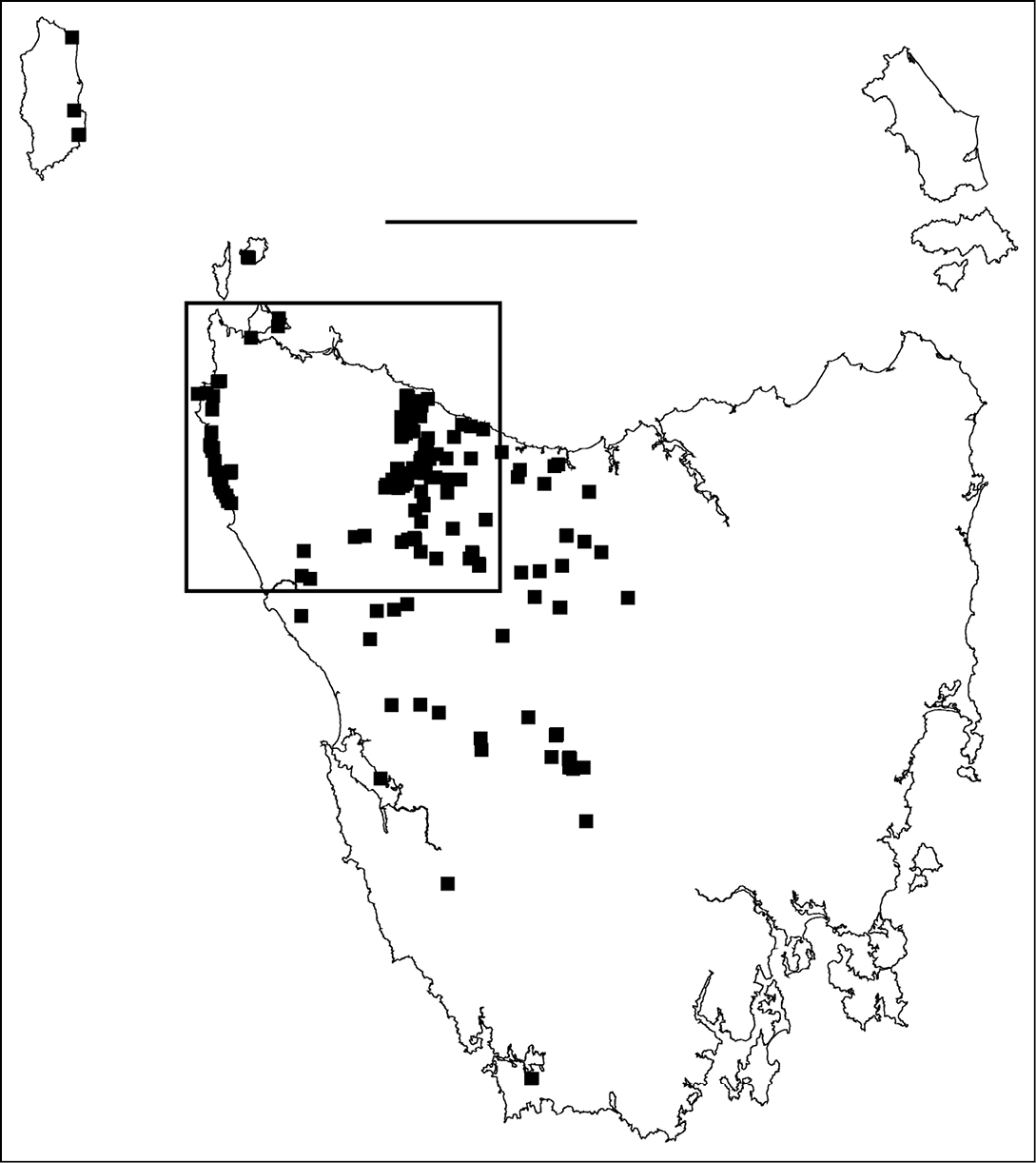

Figure 1. Localities for male Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum. Scale bar = 100 km. Rectangle indicates map extent in Figs 2–6.

Colour in the two species fades quickly in alcohol. Preserved females cannot be identified by colour after a few months, and long-preserved museum specimens can only be identified by examining the gonopods of mature males.

Millipede samplingFor the present study I collected Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum by hand during the daytime at 351 sites in northwest Tasmania between July 2009 and August 2011. Adults are night-wandering and can be found sheltering during the day under loose fragments of bark on dead tree stems and branches, under flat pieces of bark and woody litter on the ground, and within narrow, curled lengths of fallen bark from eucalypt crown branches. At most sites adults were collected within 30 minutes, but at sites where Tasmaniosoma spp. were uncommon I extended the search to ca 1 hour. Several sites were searched on more than one field day before Tasmaniosoma spp. were found, and a number of specimens were kindly provided by other collectors during the study period. All specimens were preserved in 80% ethanol and deposited as registered lots in the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston, Tasmania.

Sites were located in the field with a handheld GPS unit, or later the same day by reference to Google Earth. Because I collected specimens over an area up to ca 1 ha at each site, the uncertainty associated with each locality was recorded as ±25 m or ±50 m as appropriate.

Note: All known specimen records for Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum are listed in the Appendix. The reader should refer to this Appendix for locations of placenames and other geographic features mentioned in the Results and Discussion sections. Site locations can be plotted from Appendix data either as UTM grid references or as latitude/longitude in GIS, or in Google Earth or other spatial data browsers using the included KML files.

Boundary estimationA parapatric boundary can be marked on a map by drawing a line equidistant from localities for each of the two species near the boundary. A ‘halfway between’ line of this kind is an appropriate estimator of the true location of the boundary if sampling localities are few and the map scale is coarse.

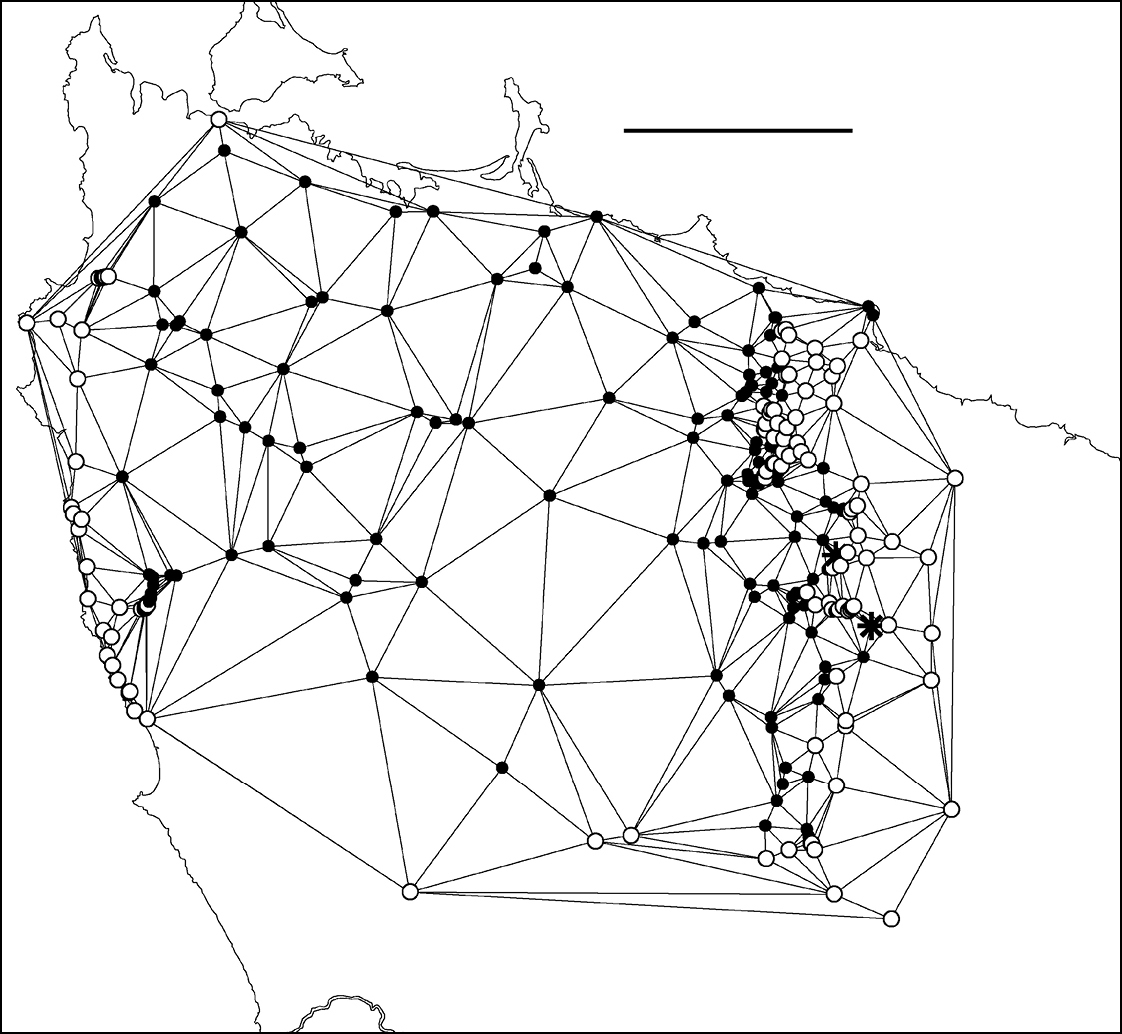

The present study generated hundreds of species localities and I was interested to trace the path of the main parapatric boundary (see below) at a scale appropriate to the spatial intensity of the sampling. I first generated a Delaunay network for male localities in the area of interest using the Delaunay triangulation tool in Quantum GIS version 1.4.0 (http://qgis.org/); see Fig. 4 and its caption for more details. I then deleted from the Delaunay polygon shapefile all triangles which had the same species at all three vertices. For clarity, I also deleted triangles running seawards from the two coastal ends of the boundary. The remaining set of 163 polygons (Fig. 5; see also its caption) consisted of triangles with one species at two of the vertices and the other species at the third. Finally, I generated centroids for the 163 triangles (Fig. 6) using the freeware Center of Mass extension (Jenness Enterprises, Flagstaff AZ, USA, http://www.jennessent.com/) for ArcView 3.2 GIS (ESRI, Redlands CA, USA).

Each of the 163 centroids is a point estimate for the location of the parapatric boundary. Where sampling localities are close together, the centroids approximate a line; see the eastern section of the boundary in Fig. 6. Where sampling localities are far apart, the centroids are diffusely distributed. The method used here is similar to triangulation wombling for scattered point data (

The GIS layers used in Fig. 7 for elevation contours, major streams, generalised geology and rainfall isohyets were sourced from the spatial data library of the Tasmanian state government (http://www.thelist.tas.gov.au) through the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery.

Results Millipede sampling overviewAdult Tasmaniosoma spp. were collected in every month of the year during the study period, but were much harder to find in the Tasmanian summer, December to March.

In northwest Tasmania, Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum appear to be most abundant in natural forest and woodland of the regional Eucalyptus species, namely Eucalyptus brookeriana, Eucalyptus delegatensis, Eucalyptus nitida, Eucalyptus obliqua, Eucalyptus ovata and Eucalyptus viminalis. Both species can also be found in riparian or fire-sere stands of Acacia dealbata and Acacia melanoxylon. Both millipede species occur in eucalypt communities ranging from open forest with an iris ground layer (Diplarrena sp.), to regrowth forest with a dense understorey of small trees (Pomaderris apetala or Leptospermum spp.), to old-growth forest with an understorey of mature rainforest tree species (Nothofagus cunninghamii, Phyllocladus aspleniifolius, Atherospermum moschatum). Neither species is easy to find in old-growth Nothofagus cunninghamii rainforest or in heathland.

Populations of both Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum appear to be tolerant of major habitat disturbance, including intense wildfire and clearfelling followed by burning and reafforestation. Both species are abundant in some plantations of Eucalyptus globulus, Eucalyptus nitens and Pinus radiata, especially first-rotation plantations established on former native forest sites and plantations closely bordering native forest, including narrow remnant strips close to watercourses. Both species are also occasionally found in small (<0.1 ha) vegetation remnants on cleared farmland, e.g. an isolated eucalypt copse or a riparian strip of Acacia melanoxylon over blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) and other weed species.

I was unable to find either species in certain apparently suitable habitat patches, despite repeated searches during the two-year study period. These distribution gaps were mainly clustered in the southeast of the study area near Waratah and Guildford, but were also close to former Poa grassland/woodland sites near Oonah. Populations of Tasmaniosoma compitale or Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum were found at sites within a few kilometres of the gaps.

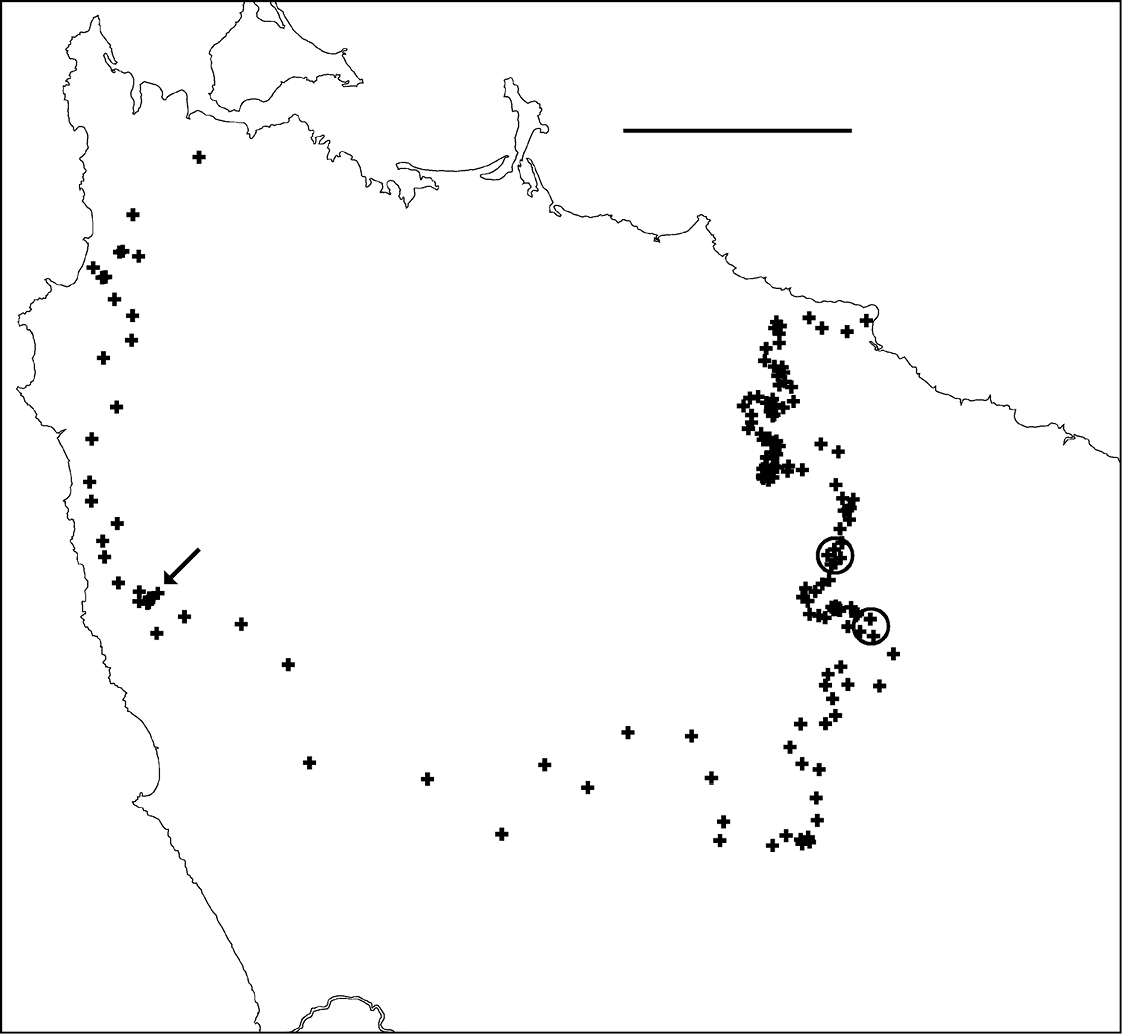

Main parapatric boundaryTasmaniosoma hickmanorum is widespread in western Tasmania but there is a ca 4000 km2 gap in its distribution in the northwest (Figs 1, 2). The gap is filled by the distribution of Tasmaniosoma compitale (Fig. 3). The main parapatric boundary between the two species is ca 230 km long (Fig. 6) and has been closely mapped along Jefferson Road southeast of Preolenna and Rebecca Spur 3 southeast of Temma. At these two locations the boundary is ca 100 m wide (Fig. 8). The boundary appears to be just as narrow along Leonards Road south of Henrietta, Lyons Road south of Lapoinya, the Murchison Highway southeast of Waratah and at the north end of Hellyer Gorge, Oonah Road west of Oonah and Robbins Island Road north of West Montagu. At these locations I was unable to collect enough males during the study period for reliable fine-scale mapping.

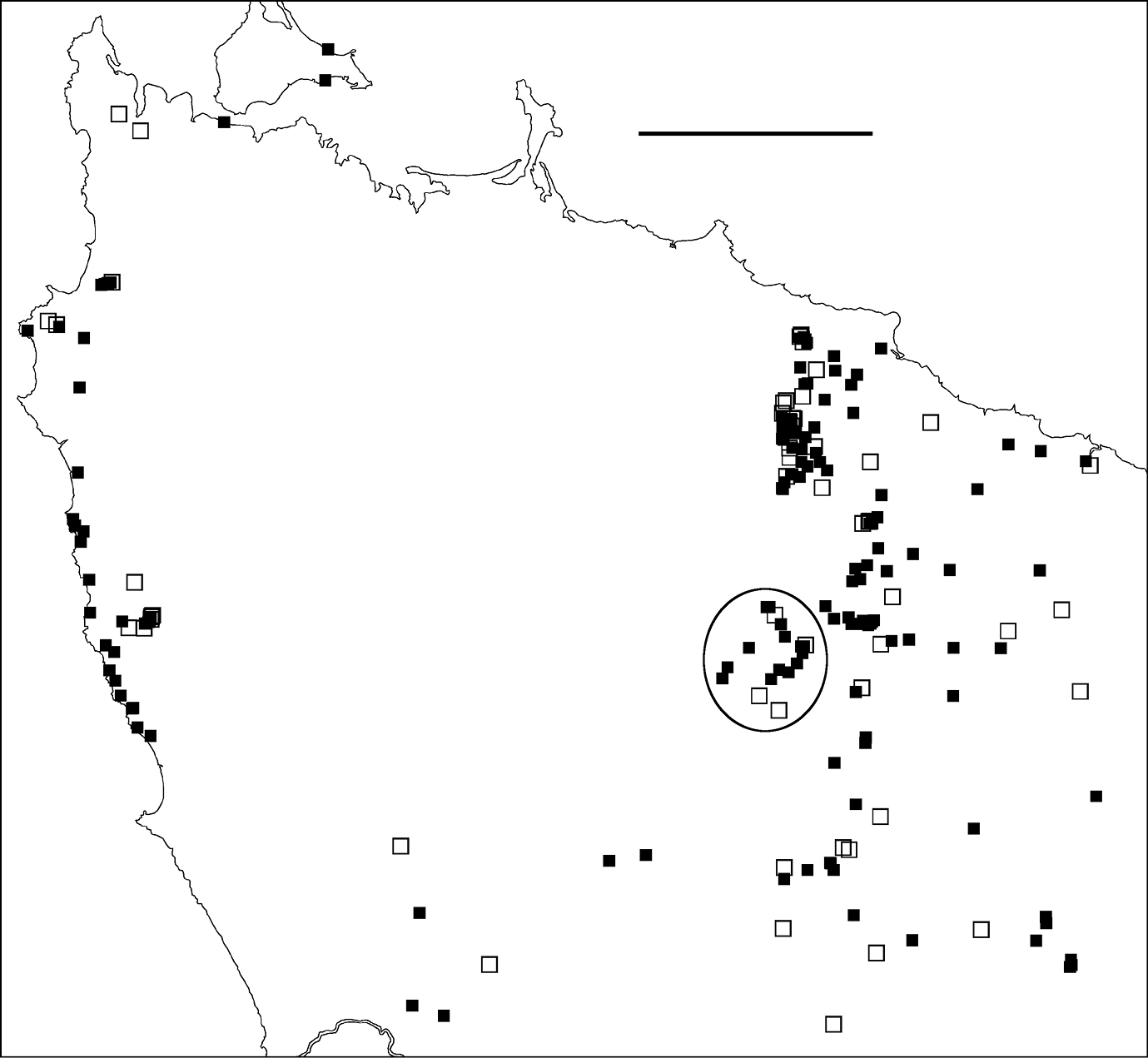

Figure 2. Localities for Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum males (filled squares) and females identified by colour (open squares). Ellipse encloses Arthur-Hellyer ‘island’ (see text for explanation). Scale bar = 25 km.

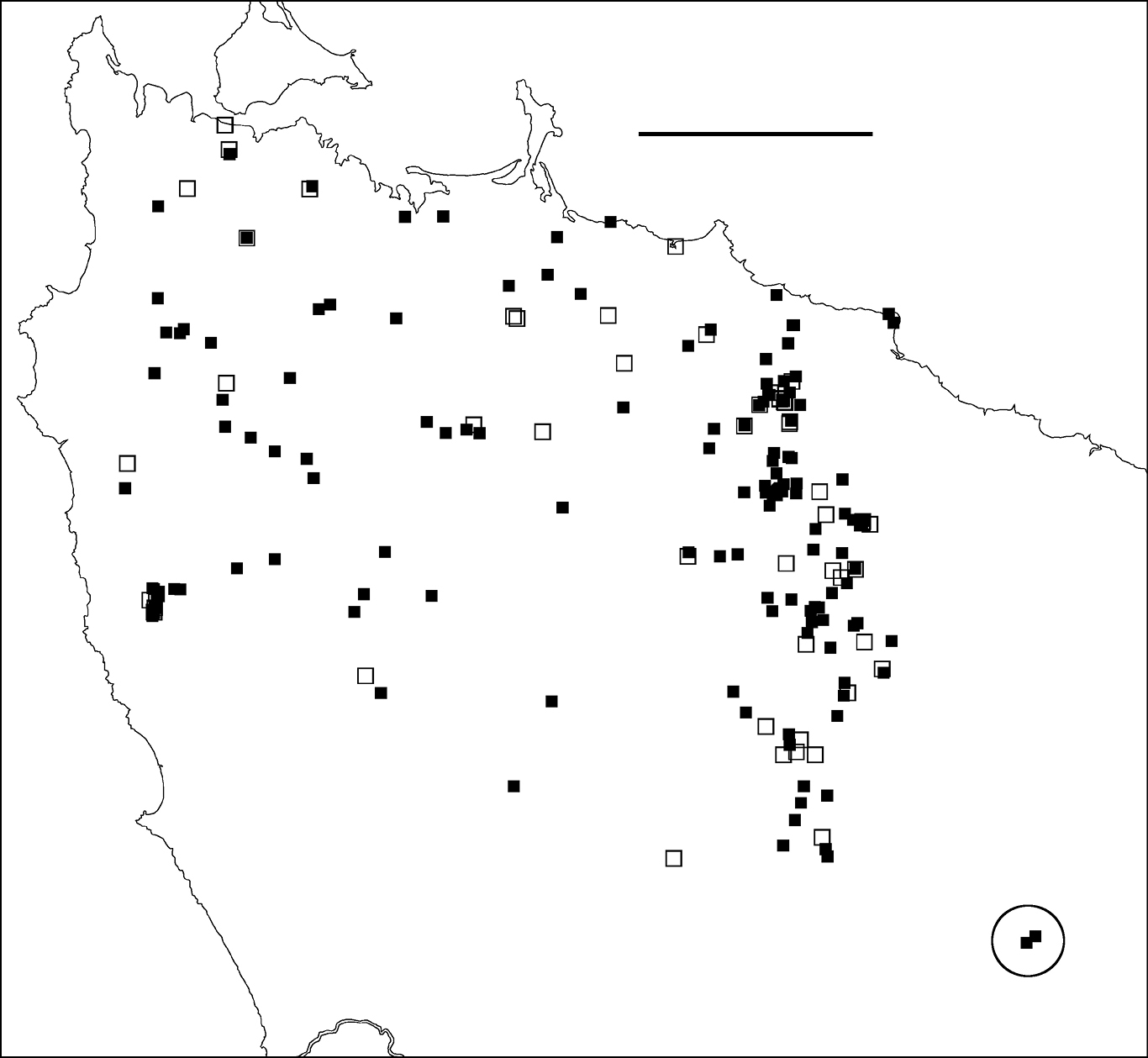

Figure 3. Localities for Tasmaniosoma compitale males (filled squares) and females identified by colour (open squares). Outliers (circled) are at the Vale of Belvoir. Scale bar = 25 km.

Boundary mapping is no longer possible near Wynyard, Redpa and other farming localities in northwest Tasmania. Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum populations persist in native vegetation remnants in these areas, but are separated by intensively managed pasture and cropland. Mapping is also difficult along the southern and southwestern sections of the main parapatric boundary, which traverses unroaded, largely wild country.

Arthur-Hellyer ‘island’A ca 40 km2 ‘island’ of Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum localities occurs in the upper reaches of the Arthur and Hellyer Rivers near Hellyer Gorge (Fig. 2), apparently enclosed by Tasmaniosoma compitale localities. The parapatric boundary of this ‘island’ has not yet been closely mapped on its eastern and northern sides, and the western and southern sections of the boundary (not yet located) are in unroaded, steeply dissected and thickly vegetated terrain.

Possible translocationsMales of Tasmaniosoma compitale were found ca 20 km within the Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum range at the Vale of Belvoir (Fig. 3). It is not yet known whether this is a naturally isolated occurrence or the result of translocation. The ca 500 ha of open grassland at the Vale has been grazed by cattle during the summer months for more than 100 years, and Tasmaniosoma compitale may have been unintentionally introduced into the area by cattle-carrying trucks.

Translocations of Tasmaniosoma compitale over shorter distances may also have occurred in intensively managed forest close to the main parapatric boundary. For example, I collected females of this species at three neighbouring sites along Ten Foot Track off Preolenna Road. The three sites are surrounded by Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum occurrences and are close to a logging road used by log-carting trucks in recent years.

Co-occurrenceAt two sites along the main parapatric boundary (Figs 4-6) I found males of Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum within a few metres of each other, on Leonards Road south of Henrietta and on Talunah Road west of Hampshire. At another 11 sites close to the main parapatric boundary I found possible co-occurrences, but at least one species was represented only by females identified by colour. At two of the latter sites, both species were found sheltering under loose bark on the same fallen tree.

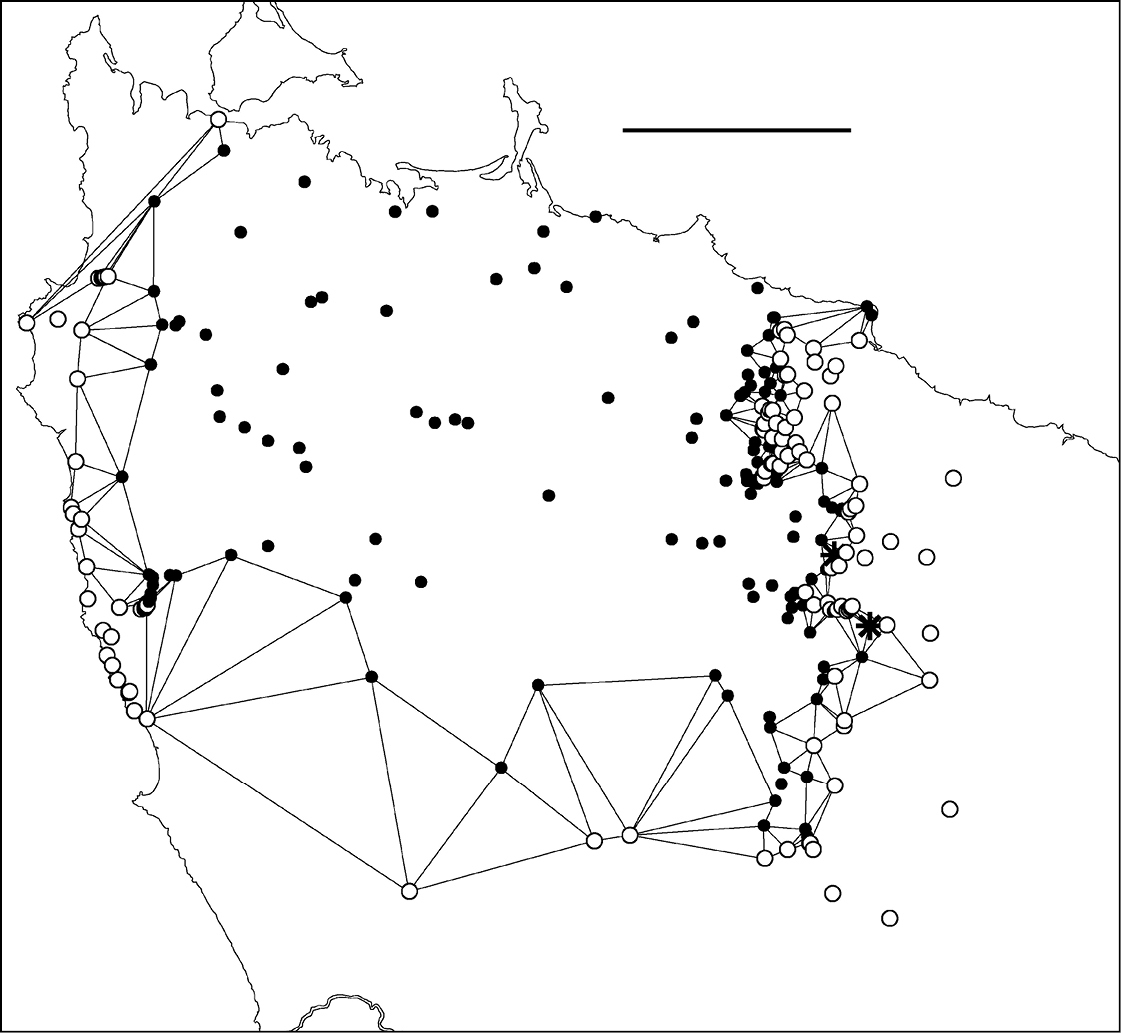

Figure 4. Delaunay triangulation of localities for male Tasmaniosoma compitale (filled circles), Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum (open circles) and co-occurrences (stars). The set of localities used has been trimmed to the vicinity of the parapatric boundary, and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum localities in the Arthur-Hellyer ‘island’ and Tasmaniosoma compitale localities at the Vale of Belvoir have been excluded. Scale bar = 25 km.

Figure 5. Edited Delaunay triangulation of localities for male Tasmaniosoma compitale (filled circles), Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum (open circles) and co-occurrences (stars); see text for explanation. Scale bar = 25 km.

Figure 6. Centroids of triangles in Figure 5. Co-occurrences of Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum males are circled. Arrow points to area shown in Figure 8. Scale bar = 25 km.

None of the males collected near the main parapatric boundary or the boundary of the Arthur-Hellyer ‘island’ had gonopods intermediate between Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum, or were intermediate in live colouring.

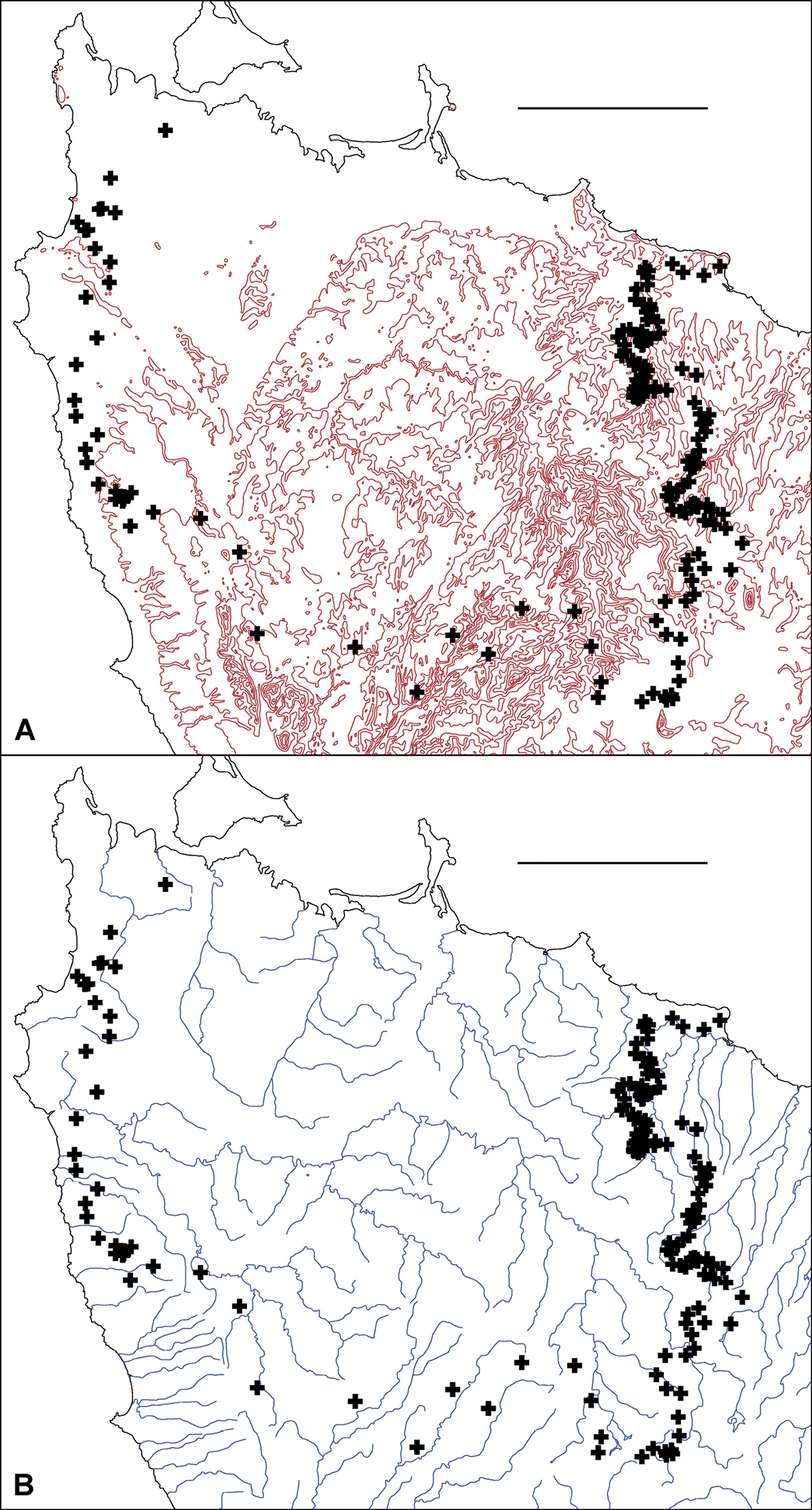

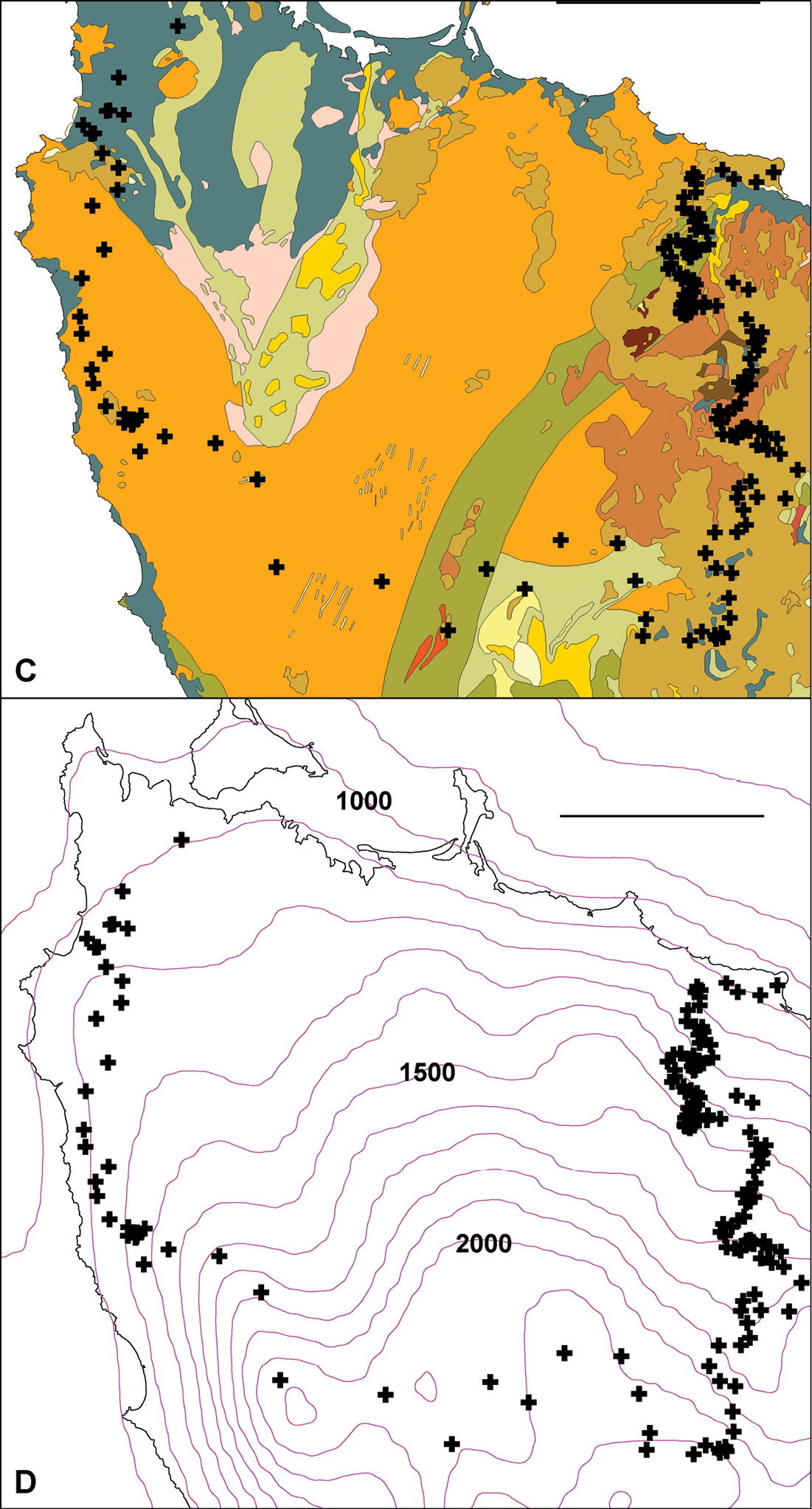

Environmental incongruenceAs shown in Fig. 7A, the main parapatric boundary rises from the north coast near Robbins Island (western section of the boundary) to 600-700 m at its southeast corner, then returns to the coast near Table Cape, ca 75 km from its starting point. It crosses most of the west coastal rivers north of Sandy Cape and the headstreams of both the major inland river systems in the region (Arthur and Pieman) before descending to the north coast; the northeast section of the boundary more or less follows the Flowerdale River (Fig. 7B). The parapatric boundary crosses numerous geological boundaries (Fig. 7C) and its eastern section runs along a fairly steep rainfall gradient (Fig. 7D), i.e. at right angles to isohyets.

Both Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum occur in a wide range of vegetation types close to the parapatric boundary. If there are major environmental boundaries which are spatially congruent with the biogeographical one separating the two species, they are not obviously related to topography, geology, climate or vegetation.

Figure 7A, B. Centroids from Fig. 6 superimposed on 100 m elevation contours A and principal rivers B. Scale bars = 25 km.

Figure 7C, D. Centroids from Fig. 6 superimposed on simplified bedrock geology C and mean annual rainfall isohyets, in mm D. In C, colours crossed by main parapatric boundary represent (anticlockwise from top left) Quaternary coastal sand and gravel (gray-blue), Precambrian siltstone and mudstone (orange), Precambrian metamorphics (green), Cambrian conglomerate and siltstone (gray-green), Tertiary basalt (light brown) and Permian glaciomarine sedimentary rocks (red-brown). Scale bars = 25 km.

The aim of this study was to map the boundary between the Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum distributions as a knowledge base for future studies of parapatry and speciation. The parapatric boundary between these two species is the longest and narrowest I am aware of in the Australian millipede fauna. It is particularly well-suited to field study because much of it is easily accessed by all-weather roads, and because sections of the boundary run through little-disturbed tracts of native vegetation, including primary forest. The two millipede species are ecologically resilient and can be very abundant in eucalypt forest at lower elevations.

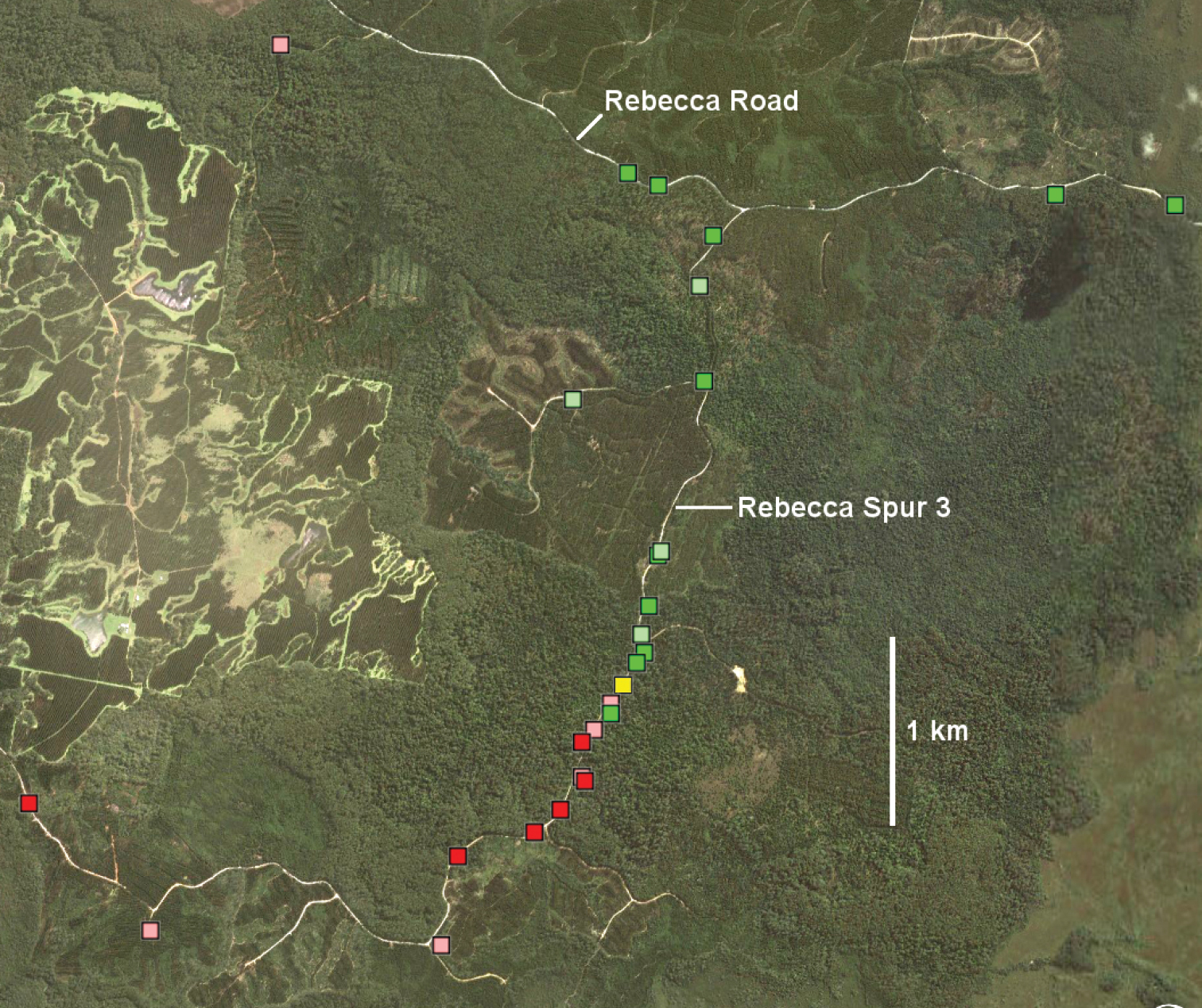

Several of the the largest and least disturbed patches of forest along the boundary are on public land managed by Forestry Tasmania, a government-owned forestry business. One such patch covers ca 12 km2 on the upper Flowerdale River between Lapoinya and Preolenna Roads, on the eastern arm of the boundary. The forest is a mosaic of formal and informal reserves, production forest and plantation, with privately owned forest on the periphery. A similar but smaller mosaic is found along Rebecca Spur 3 and south of the Rebecca Road – Rebecca Spur 3 junction (Fig. 8) on the western arm of the boundary.

Figure 8. Rebecca Spur 3 area (marked with arrow in Fig. 6) in Google Earth image dated 11 October 2010. Markers: Tasmaniosoma compitale males (darker green) and females identified by colour (lighter green), Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum males (darker red) and females identified by colour (lighter red), and possible co-occurrence of females identified by colour (yellow).

The parapatric boundary also crosses private land. Because the future of privately owned forest is less certain in Tasmania than that of formally reserved forest on public land, future field studies on suitable private blocks might be given a high priority. I was allowed access during the study period to a large private block near Henrietta, just north of the Takone Road. The Henrietta block carries even-aged eucalypt regrowth and populations of both Tasmaniosoma compitale and Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum.

An unanswered question is whether the two millipede species are well-distributed across heathland near the west coast. Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum is abundant in shrubby coastal vegetation, and to the east Tasmaniosoma compitale has been found close to scattered, small eucalypts in heath. As currently estimated (Fig. 6), the main parapatric boundary crosses ca 50 km of heathland in the formally reserved Arthur-Pieman Conservation Area.

I thank Matthew French, Daniel Lester, Renate van Riet and my wife Trina Moule for help with collecting, and Mark Alexander and Kevin Bonham for additional specimens. I am especially grateful to the many friendly farmers and other small-property owners in northwest Tasmania who gave me access to their properties for millipede sampling, and to the larger-property owners and managers who offered access through more formal protocols: Forestry Tasmania (represented by Nigel Foss), Grange Resources (Daniel Lester), Gunns Ltd (Robert Onfray) and the Van Diemens Land Company (Brent Anstis). This study was funded by the author.

Specimen records as of 8 August 2011 for Tasmaniosoma compitale, Tasmaniosoma hickmanorum and unassigned females of these species. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.156.1893.app

Description. The compressed file contains complete records in the annotated CSV file ‘Parapatry_records.csv’ and separate KML files for males of the two species, females and juveniles of the two species (identified by colour), co-occurrences, and females not assignable to either species. Each KML record has an associated museum registration number and users should refer to ‘Parapatry_records.csv’ for more information on that record.